CHAPTER 9

SON OF GOD AND CHILD OF GOD

When it comes to your personal identity, many things change throughout your lifetimes. Your age, job, where you live, and even your personality and character can be different from one decade to another. For most people, families are among the few constants that stay with us from the beginning to the end of our lives. Without the most drastic of actions, and despite fractured relationships, among your most influential relationships are your relatives, and most significantly your parents. And this is especially the case when one of your parents is noteworthy for some reason; it’s hard not to live in the shadow of a famous (or infamous) father or mother. While being a son or a daughter is foremost when you are growing up, the impact of your parents on your identity goes the distance. How many of us have said to ourselves long into adulthood, often with some irritation: “Oh dear, I’m turning into my father/mother”?

Who are we? The Bible has a number of metaphorical ways of talking about the identity of God’s people. God’s relationship with us is compared to that of king and subject, master and servant, husband and wife, shepherd and sheep, potter and clay, and so on. In this chapter we investigate what is arguably the most powerful and pervasive of such identity metaphors: father and child.

What you call yourself is of fundamental importance in forming your identity. What does it mean to say that God is our Father and that we are God’s children? In order to answer this question, we must begin by considering how to interpret a metaphor.1 Sometimes people regard metaphors as sort of decorative additions to the more important direct communication, more “icing on the cake” than the cake itself. This view is mistaken, and it leads to a seriously stunted reading of the Bible, which is “full to the brim” of figurative language. Metaphors communicate more meaning than literal modes of speaking, not less.

“Words, including self-designations, have an ability to lead to a radical reinterpretation of identity.”

Paul Trebilco2

With a clear understanding of metaphorical language in place, we will then consider the two sides of the father/child metaphor: (1) being a child or son of God; and (2) being brothers and sisters in God’s family. This metaphor is widely used in the Bible.

UNDERSTANDING METAPHORS

What is a metaphor? What does it mean to say that I am a child of God or that we are brothers and sisters in God’s family?

Janet Martin Soskice contends that the many theories of how metaphors work fall into three basic groups. The first regards metaphors as decorative ways of saying what could be said literally. But this view is clearly mistaken in ignoring the emotive responses that metaphors arouse. Simply to “translate” a metaphor into straightforward language is to miss the metaphor’s dynamism. A second group stresses the affective impact a metaphor exerts, the feelings it evokes. But this view goes too far in the other direction in denying that a metaphor contributes any increment to meaning. For if thoughts and feelings can be expressed in words, then at least part of a metaphor’s meaning may be expressed literally, even if by doing so one risks blunting the affective impact. An adequate account of metaphors must consider both their cognitive meaning and emotive effect. Thus, a third group considers metaphors to be unique cognitive vehicles enabling one to say something that can be said in no other way.3

Here are some examples of biblical metaphors:

God is a rock.

The Lord is my shepherd.

The Lord God is a sun and a shield.

Jesus is the door.

Jesus is the true vine.

Judah is a lion’s cub.

Herod is a fox.

You are the salt of the earth.

You are God’s children.

You are brothers and sisters in God’s family.

My own definition of a metaphor points to three essential elements:

Metaphors are a form of communication that uses a familiar image to (1) say something (2) memorably (3) with feeling.

Metaphors communicate more meaning than propositional or literal language in that, rightly understood, they both inform and also move the hearer. And by appealing to something that is concrete and known, like all figurative language, a good metaphor sticks in the mind and is easily recalled. The trick with interpretation is to determine what feelings the metaphor evokes, its affective impact, as well as what we learn from the metaphor, that is, its cognitive meaning.

There are two things to consider for accurate interpretation of metaphors. The first is context—sometimes clues are given in the literary context of a metaphor that help explain its meaning. And secondly, milieu—we need to determine the cultural setting of the image in question to ascertain its regular associations. The milieu of biblical metaphors can be ascertained both from extra-biblical texts and from the Bible itself.

“Metaphors are incongruous conjunctions of two images—or two semantic fields—that turn out, upon reflection, to be like one another in ways not ordinarily recognized. They shock us into thought by positing unexpected analogies.”

Richard Hays4

“Metaphor consists in bringing two sets of ideas close together, close enough for a spark to jump . . . so that the spark, in jumping, illuminates for a moment the whole area around, changing perceptions as it does so.”

N. T. Wright5

Paul’s use of family metaphors, for example, is explicitly tied to Old Testament texts. In Romans 9:25–26, Paul claims that gentile Christians have the privilege of being called “children of the living God” on the basis of Hosea 1:10. In Galatians 4:27–31, Paul quotes Isaiah 54:1 to support the Galatian Christians’ new familial status as “children of the promise” (Gal 4:28). And in 2 Corinthians 6:18, Paul’s supports his description of the Corinthian community as God’s “sons” and “daughters” by a quotation of 2 Samuel 7:14.

As a case study in understanding metaphors, consider “God is a rock”—a biblical metaphor with a long history. This metaphor is a conjunction of two apparently incongruous things. Yet after reflecting on their respective semantic fields, they turn out to be alike in certain ways. What is the comparison of God to a rock saying? The difficulty in interpreting a metaphor is working out which features of each semantic field are being drawn upon in the comparison.6 Which associations are being highlighted and which are being suppressed? In other words, what is the metaphor’s cognitive meaning? And how is God being compared to a rock meant to make us feel? What is its affective impact?

The use of this metaphor in the Psalms is revealing:

The LORD is my rock, my fortress and my deliverer;

my God is my rock, in whom I take refuge,

my shield and the horn of my salvation, my stronghold. (Ps 18:2; see also 2 Sam 22:2–3, 32–33; Ps 62:2)

The point of comparing God to a rock is to highlight God’s strength and protection. Rocks withstand pressure, enduring even when massive force is brought against them. In line with this understanding, the Aramaic translations of the Pentateuch take God being a rock in Deuteronomy 32 to refer to his strength and paraphrase the verses in question as describing God as “the Strong One.”7 Given that everyone has some experience of rocks, comparing God to a rock is memorable. And this carries with it feelings of security and safety that would be lacking if it were reduced to a literal utterance about God.

We may present an understanding of the metaphor of God as a rock in a diagram:

DIVINE ADOPTION

As we noted in chapter three, the family to which you belong is of critical importance to your identity. And as we will see, being a member of God’s family picks up on many of these associations.

What then are we to make of the “family of God” metaphor? Clearly it communicates memorably, since having parents and siblings is such a common human experience. But which associations of the imagery are the points of the comparison? What feelings are communicated by the family metaphor? What do we learn from its use in various literary contexts? What is its milieu? What cultural associations did fathers, sons, children, and siblings carry in Bible times?

In 1973, J. I. Packer pointed to the surprising lack of interest in the topic of divine adoption. He lamented “the strange fact that the truth of adoption has been little regarded in Christian history. . . . Apart from two last-century books, now scarcely known . . . there is no evangelical writing on it, nor has there been at any time since the Reformation.”8 Fortunately, the tide has turned in recent times with several major contributions to investigating the topic appearing.9 Our focus in this book is on the critical importance of God adopting us into his family for the subject of the personal and corporate identity of believers in Christ.

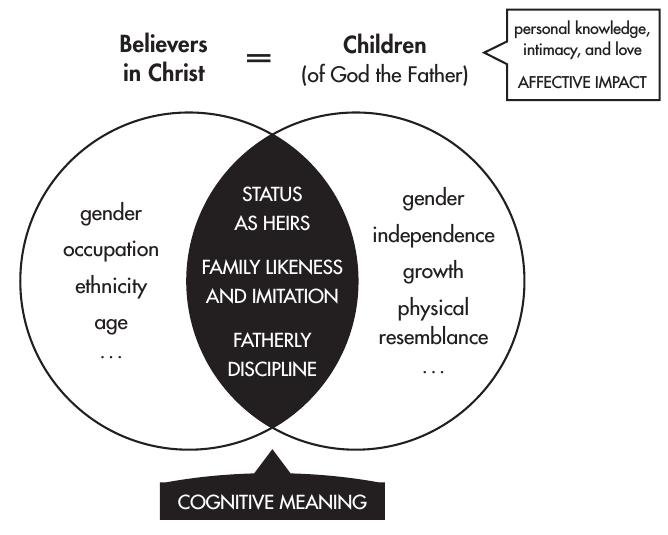

The family of God metaphor is both remarkably widespread in the Bible and impressively flexible in its application. By way of preview, we may present the main features of the metaphor as it relates to our status as children of God in the diagram above. The second major section in this chapter will consider our identity as brothers and sisters in God’s family.

Which associations are being highlighted and suppressed in this metaphor? In other words, what is the metaphor’s cognitive meaning? And how is being compared to children of God meant to make us feel? What is its affective impact?

The following two sections expound the major aspects of the metaphor: 1) its affective impact, namely, personal knowledge, intimacy, and love; and 2) its cognitive meaning with reference to becoming heirs of God, displaying the family likeness, and receiving fatherly discipline.

The Affective Impact

The affective impact of saying that God is our Father is easily determined. In the biblical cultures as well as throughout the Bible, parents are those who love and care for their children. Jesus took this for granted in teaching about our heavenly Father:

Which of you fathers, if your son asks for a fish, will give him a snake instead? Or if he asks for an egg, will give him a scorpion? If you then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him! (Luke 11:11–13; see also Matt 7:9–11)

When God declares that Jesus is his Son at Jesus’s baptism and transfiguration, as we saw in chapter eight, he identifies him as the one “whom I love.” And when Paul speaks of our adoption into God’s family, he mentions God’s love for both his adopted sons and his only begotten Son:

In love he predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ, in accordance with his pleasure and will—to the praise of his glorious grace, which he has freely given us in the One he loves. (Eph 1:4–6)

Jesus drew out another dimension of the father-child relationship in the Good Shepherd discourse in the Fourth Gospel in a text we considered in chapter seven:

I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me—just as the Father knows me and I know the Father—and I lay down my life for the sheep. (John 10:14–15)

Jesus compared the knowledge he has of his “sheep” to the intimate and personal knowledge a father has of his children. And as we saw in chapters six and seven, to be known by God is be known intimately and personally as his children.

Thus, the metaphor of believers in Christ as God’s children carries with it feelings of love, intimacy, and personal knowledge. These are not things to do or even learn, but rather things to sense and embrace—that is, the affective impact of the metaphor.

The Cognitive Meaning

What does the identity of being a son or child of God entail? When it comes to cognitive meaning, there are three regular uses to which the metaphor of believers as members of God’s family is put in the Bible. Put another way, three things are highlighted as common to both believers in Christ and children. (See the common set in the Venn diagram above.)

Heirs with an Inheritance

The first regular use is this: as children of God, believers have the status as God’s heirs and coheirs with Christ awaiting an eternal inheritance.

The theme of heirs and inheritance has a long and colorful history in the Bible. Abraham’s first response to God’s call in Genesis 15 concerns his heir:

Abram said, “Sovereign LORD, what can you give me since I remain childless and the one who will inherit my estate is Eliezer of Damascus?” And Abram said, “You have given me no children; so a servant in my household will be my heir.” (Gen 15:2–3)

Later in Genesis, conflict erupts between Sarah and her maidservant Hagar over whether Ishmael or Isaac would be Abraham’s heir. Sarah said to Abraham: “Get rid of that slave woman and her son, for that woman’s son will never share in the inheritance with my son Isaac” (Gen 21:10).

Paul deals with believers as heirs at length in Galatians 3:7–4:7. In response to the Judaizing opponents, who insisted that the Abrahamic inheritance was restricted to those who put themselves under the law by being circumcised, Paul argues that Abraham’s true children are those who put their faith in Jesus: “those who have faith are children of Abraham” (Gal 3:7). In Galatians 5:21, Paul indicates that the inheritance in view is the kingdom of God (see also 1 Cor 6:9–10; Eph 5:5). In Titus 3:7, on the other hand, Paul defines our inheritance in a different but related manner: by grace believers “become heirs having the hope of eternal life.”

Paul links believers being children and heirs with Jesus Christ being the Son of God:

When the time came to completion, God sent His Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of His Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba, Father!” So you are no longer a slave but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God. (Gal 4:4–7 HCSB)

In Paul’s view, Christ the Son of God is the true heir (see also Matt 21:38), and believers become co-heirs by being united to him.

The language of sonship raises a major problem of interpretation and translation. Are those who are in union with Christ God’s sons or his children? Does it matter? Is the language of sonship necessary to communicate the notion that we are heirs of God? Many modern translations, including the NIV, render the Greek huios in Galatians 4:7 (and elsewhere) as “child” rather than as “son”: “So you are no longer a slave, but God’s child; and since you are his child, God has made you also an heir.” While Greek huios in this verse is clearly generic and includes believers of both genders, there are two possible reasons for retaining “son” in translation. The first is the fact that in Bible times, it was the right of the eldest son in the family to be the primary heir (see, e.g., Deut 21:15–17). However, while technically the language of sonship does forge a link to Christians being heirs, we should note that Paul himself does not always insist on using it. In Romans 8:16–17, he discusses Christians being heirs, describing us as God’s “children,” tekna. Other New Testament books, such as the Gospel of John, talk in terms of believers as “children of God” (John 1:12) with Jesus as “the one and only Son” (John 1:18; 3:16).

Different authors in the New Testament develop the metaphor of believers as God’s children and part of God’s family in different ways. Nonetheless, there is a second reason for retaining the language of sonship, at least in some contexts, so long as it is understood that the term is gender inclusive: it reminds us that we are part of God’s family and heirs thanks to the Son of God. In other words, we are sons of God precisely because he is the Son of God. Julie Canlis writes: “I am unwilling to drop the gendered term ‘sonship,’ as our ‘sonship’ is founded upon Christ’s own Sonship. For those who find the term suspect, I do not think it can be interchanged with all sorts of terms like ‘becoming children of God’ or ‘being adopted’ . . . these lose christological clarity.”10

“The concept of the believer’s inheritance highlights the dignity of the family relationship of the believer in Christ. No higher position or greater wealth can an individual acquire than to become an heir of God through faith in Christ.”

William E. Brown11

My policy in this book is to use the language of “children of God” rather than “sons of God” unless the notion of sonship has a direct bearing on the point I am making. In those cases readers should be aware that “sons of God” carries a generic sense and refers to all believers in Christ, both male and female.

Family Likeness and Imitation

As children of God, believers have the status as God’s heirs and coheirs with Christ awaiting an eternal inheritance. A second cognitive meaning of the metaphor of the family of God is this: As children of God, believers are to imitate the Father and the Son. On this point we see the profoundly formative nature of the identity of being children of God for our behavior and character.

In terms of the milieu of fathers and sons, D. A. Carson notes:

In the ancient world, the overwhelming majority of sons took up the same vocation as that of their fathers. The sons of farmers became farmers, the sons of fishermen, became fishermen—and in both cases the sons learned their trade from their fathers. . . . These realities established their identity. That is why Jesus can be identified as “the carpenter’s son” (Matt 13:55) and, presumably after the death of his (apparent) father Joseph, as himself “the carpenter” (Mark 6:3).12

With this in mind, it makes perfect sense for Jesus to say, “whatever the Father does the Son also does” (John 5:19).

The very language of “son of [something]” itself points to a relationship of resemblance. In 2 Kings 6:32 a “son of a murderer” is a “murderer” and is translated as such (cf. NASB and NIV). Likewise, the “son of might” is a “fighter” (2 Sam 17:10), and Jesus names James son of Zebedee and his brother John, “Boanerges, which means ‘sons of thunder’ ” (Mark 3:17), presumably to match their passionate and volatile character. In John 8:44 Jesus says of those opposing him: “You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires.”

Like it or not, fathers shape the identity of their sons. On one occasion, my nine-year old son said something that was mildly offensive. When I corrected him, my wife pointed out a certain similarity with me. Toby responded in his own defense: “You taught me to be myself!”

In this light, not surprisingly, the Bible has so much to say about imitating God and Christ. To be God’s child is to reflect the family likeness. Ephesians 5:1–2 mentions the imitation of both God and Christ:

Follow God’s example, therefore, as dearly loved children and walk in the way of love, just as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God.

Let’s begin with the imitation of God. This theme goes back to Leviticus where God tells his people to “be holy, because I, the LORD your God, am holy” (Lev 19:2; see also 20:7, 26; 1 Pet 1:16). Jesus carried on the tradition by telling his disciples to love their enemies, “that you may be children of your Father in heaven” (Matt 5:44–45), and to “be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt 5:48). To avoid a superficial survey of the subject, we will focus on one text, the letter to the Ephesians. As Ephesians 5:1 indicates (see above), imitating God is clearly linked to the child/parent relationship.13

The theme of imitating God is subtly present in the second half of Ephesians and has links to the first half. In general terms, it is noteworthy that believers are “created to be like God in true righteousness and holiness” (Eph 4:24). And the call to unity in Ephesians 4:3, to “make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit,” is based on the oneness of God, that there is “one Lord” and “one God and Father of all” (Eph 4:5–6).

“How can we be sure that we are adopted children of God? The Spirit is the answer. The Spirit jointly bears witness with our spirits that we are children of God (Rom 8:16). . . . The very fact that the Christian can pray as a child of the Father rather than address God like a slave addressing a master is evidence of the Spirit’s witness and adoption.”

Graham A. Cole14

Moreover, the theme of unity is expanded with a call to “be completely humble and gentle; be patient, bearing with one another in love” (Eph 4:2). As Roy Ciampa notes, “it does not take much reflection to realize that the first half of the letter had made it clear that those same qualities had marked God’s own treatment of the readers”15—it was out of God’s great mercy and love that he had given them new life in Christ. Likewise in Ephesians 4:32, Paul tells the Ephesian Christians to “be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you.” Ciampa writes: “It is natural and expected that children will imitate their parents. . . . What God has modeled for believers is his loving nature.”16

The theme of imitating God is also implicit in the pervasive “walking” motif in Ephesians 4–6, using the Greek word peripateō as a metaphor for daily conduct.17 Believers are not to “walk as the Gentiles do” (Eph 4:17 ESV), as you “once walked, following the course of this world” (Eph 2:2 ESV). Instead, we are to “walk in love” (Eph 5:2 ESV); “Walk as children of light” (Eph 5:8 ESV); and walk in wisdom (Eph 5:15 ESV). Significantly, love, light, and wisdom “were all well-known divine attributes,”18 and hence the call to walk in love, light, and wisdom is a call to walk in God’s footsteps. Equally, Paul lists “the fruit of the light” as “all goodness, righteousness and truth” (Eph 5:9), which are also qualities associated with God himself.

Imitating Christ is even more prominent in the New Testament than imitating God.19 Following the example of Jesus Christ is enjoined in many texts. Jesus told his disciples: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23). Having washed his disciples’ feet, he said, “I have set you an example that you should do as I have done for you” (John 13:15). Paul exhorts the Corinthians, “Follow my example, as I follow the example of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1). He commends the Thessalonians who “became imitators of us and of the Lord” (1 Thess 1:6a). And he instructs the Philippians, “In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus” (Phil 2:5). Accordingly, Peter reminds his readers, “Christ suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps” (1 Pet 2:21).

But is the imitation of Christ Jesus connected to the metaphor of believers as members of God’s family? In many cases it is. In Romans, for example, being conformed to the image of God’s Son is an integrative theme for Paul’s teaching about the Christian life.20 The key text is Romans 8:29:

For those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brothers and sisters.

The older brother Jesus is the model for his younger siblings. Leon Morris puts it well:

It is God’s plan that his people become like his Son, not that they should muddle along in a modest respectability. We should be in no doubt as to the high standard that Paul sets for Christian people. We have been admitted to the heavenly family; we are brothers [and sisters] in that family and we call God “Father”. We are accordingly to live as members of the family, and that means being made like our elder Brother. This is all part of God’s predestination; he predestined us not only to be released from an unpleasant predicament, but in order that we might become like his Son.21

That Jesus is the template to which his brothers and sisters are to conform is evident across Romans. The language of obedience lies at the heart of the Christian life. The letter is framed by two references to “the obedience that comes from faith” (Rom 1:5 and 16:26). Paul describes his own obedience in Romans 15:17–19 and calls for Christians not to obey sin but rather to live lives of “obedience, which leads to righteousness” (Rom 6:16; see also 6:12). He also commends the Roman Christians in that “Everyone has heard about your obedience” (Rom 16:19). It is no accident that when Paul explains the basis of our justification, he points to the obedience of Jesus Christ: “For just as through the disobedience of the one man the many were made sinners, so also through the obedience of the one man the many will be made righteous” (Rom 5:19). As God’s children, we are to be obedient because Jesus the Son of God obeyed God.

Significantly, Paul’s practical teaching in Romans 12–15 is driven by the goal of conformity to the pattern of God’s Son. The call in Romans 12:2 not to “conform to the pattern of this world,” but to “be transformed by the renewing of your mind” signals the beginning of the major section of explicit exhortation in the letter. Michael Thompson observes that the call to mind renewal recalls the depraved mind of Romans 1:18–32 and represents its reversal.22 According to Thompson, “underpinning 12:1–2 is Jesus’s foundational and exemplary sacrifice. For Paul, Christ’s image is the goal of the transforming process.”23 Offering ourselves as “living sacrifices” in Romans 12:1 recalls the application of cultic language to Jesus’s atoning death in Romans.24 Whereas Jesus’s sacrifice necessitated his death, Paul points out that ours is a living sacrifice. Furthermore, the language of being “transformed” (metamorphousthe) in our behavior in Romans 12:2 echoes the goal of being “conformed” (summorphos) to the image of God’s Son in Romans 8:29.

The closing verse of Romans 13 confirms that Paul had Jesus in mind in Romans 12–13 as he shares his vision of humanity: “Clothe yourselves with the Lord Jesus Christ, and do not think about how to gratify the desires of the flesh” (Rom 13:14). Likewise, Paul’s advice in Romans 14:1–15:7 about the need to accept one another in disagreements over disputable matters is reinforced by the example of Jesus:

Each of us should please our neighbors for their good, to build them up. For even Christ did not please himself but, as it is written: “The insults of those who insult you have fallen on me.” (Rom 15:2–3)

Fatherly Discipline

As children of God, believers have the status as heirs of God and must imitate the Father and the Son. A third dimension of the metaphor is this: as children of God, believers are disciplined by God, our loving heavenly Father, so that we might grow into full maturity.

One of the main associations of what it means to be a father in the Old Testament is the task of disciplining children. In Proverbs, father-like sages make frequent reference to the need to be careful to “discipline” your children (Prov 13:24), to “rebuke” them when necessary (1:25; see also 10:17), and on occasion to use “the rod of discipline” (22:15; see also 10:13; 23:13–14). The responsibility to discipline was based on the premise that fathers were to be obeyed: “A wise son heeds his father’s instruction” (Prov 13:1a; see also 15:5). In Proverbs 3:12, the Lord is compared to a caring father who “disciplines those he loves.”

Such discipline is underscored with respect to the Davidic king in 2 Samuel 7:14: “I will be his father, and he will be my son. When he does wrong, I will punish him with a rod wielded by men.” And God promises to do the same for all of his people to bring them to maturity: “Know then in your heart that as a man disciplines his son, so the LORD your God disciplines you” (Deut 8:5).

Hebrews 12:5–11 exhorts readers along these lines, quoting Proverbs 3:11–12 as support.25 Notice how the passage is explicitly framed by the identity of God’s people as sons of God their Father:

And have you forgotten the exhortation addressed to you as sons?

“My son, do not scorn the Lord’s discipline

or give up when he corrects you.

For the Lord disciplines the one he loves

and chastises every son he accepts.” [Prov 3:11–12]

Endure your suffering as discipline; God is treating you as sons. For what son is there that a father does not discipline? But if you do not experience discipline, something all sons have shared in, then you are illegitimate and are not sons. Besides, we have experienced discipline from our earthly fathers and we respected them; shall we not submit ourselves all the more to the Father of spirits and receive life? For they disciplined us for a little while as seemed good to them, but he does so for our benefit, that we may share his holiness. Now all discipline seems painful at the time, not joyful. But later it produces the fruit of peace and righteousness for those trained by it. (Heb 12:5–11 NET)

“The Christian’s sonship is derived from our relationship with Christ as adopted sons. On this basis New Testament believers typically identified one another as ‘brothers’ [and ‘sisters’].”

R. A. Taylor and E. R. Clendenen26

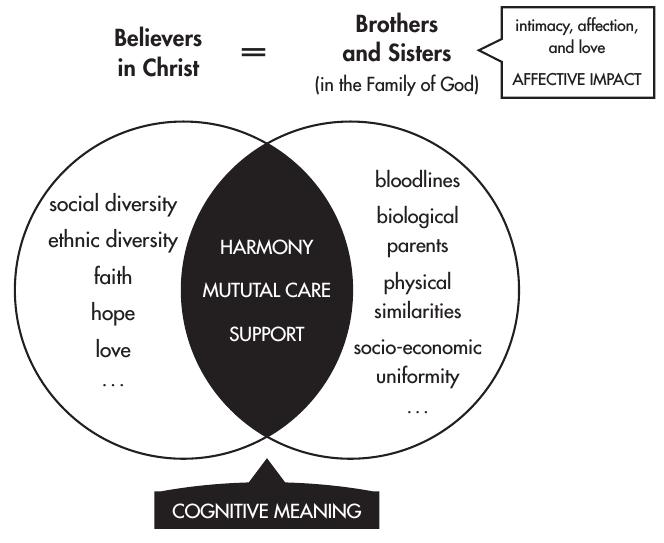

BROTHERS AND SISTERS IN THE FAMILY OF GOD

Who did the first Christians think they were? What did they call themselves? In his study entitled Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament, Paul Trebilco lists the following titles and descriptions favored by the first Christians: believers, saints, the church, disciples, the Way, Christians, and brothers and sisters (Greek adelphoi). It is significant for our investigation of personal identity that “adelphoi is the most common term in use as a designation for Christians in the New Testament.”27 In fact, as Trevor Burke notes, “the frequency with which the early Christian movement in general, and the apostle Paul in particular, employed this expression [brothers and sisters] is unprecedented.”28

The extensive use of sibling language in the early church stood out in the ancient world, with the one exception being Jews whose kinship could be traced in general terms through blood lines.29 While the language of brother and sister was not unheard of in pagan philosophical circles, groups like the Epicureans or Cynics preferred the language of friendship. Paul, on the other hand, avoids calling Christians his friends. Abraham Malherbe notes that “Paul does not speak of friends or friendship but of brotherly love. He was familiar with the conventional discussions about friendship but studiously avoided using the word itself.”30

A possible reason for Paul’s preference for sibling language is his concern not just for individual morality but also for the corporate life of God’s family. Wayne Meeks writes: “We cannot begin to understand the process of moral formation [in Paul’s letters] until we see that it is inextricable from the process by which distinctive communities were taking shape. Making morals means making community.”31 The use of adelphoi shows that a child of God is not only an individual identity, but also a corporate one.

“The very widespread use of adelphoi across the New Testament shows how widely it was in use amongst the earliest Christians, and that it can be seen as a unifying factor across the movement. Its importance can be related to the pervasive ethos of being fictive kinship groups in early Christianity. . . . This speaks of a sense of love, mutuality, togetherness, and belonging and also testifies that the early Christians saw themselves as a distinctive group over against other groups. This use of adelphoi both reflects and enhances the identity and cohesion of early Christian groups.”

Paul Trebilco32

“Because the English language does not distinguish between the second-person singular and plural, translations do not communicate that Paul’s letters are a dialogue between him and the entire community. . . . Even private correspondence to Philemon addresses the whole church.”

Michael B. Thompson33

While Jesus was still talking to the crowd, his mother and brothers stood outside, wanting to speak to him. Someone told him, “Your mother and brothers are standing outside, wanting to speak to you.” He replied to him, “Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” Pointing to his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers. For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” (Matt 12:46–50; see also Mark 3:31–35; Luke 8:19–21)

What gave rise to the widespread use of the language of brother and sister in the early church? It seems that four factors worked together to make the language stick:

1. Historically, there was a strong precedent of the same language in the Old Testament for Israel as the people of God.34

2. Jesus taught that his followers were a new family.35

3. “The members of the communities were adelphoi [brothers and sisters] because Jesus is the firstborn Son (Rom 8:29).”36

4. The early church had a “powerful experience of community as ‘a new family.’ ”37

If a metaphor is a form of communication that uses an image to say something memorably with feeling, what is the affective impact of the comparison of believers in Christ to brothers and sisters? And what is its meaning?

Affective Impact: Love and Intimacy

The feelings elicited by the family of God metaphor are not hard to discern. If the affective impact of having God as your Father is the experience of love and intimacy with God (see above), a corresponding love for and intimacy with fellow believers is communicated by the family of God metaphor.

The compound Greek word philadelphia, “love for brothers and sisters,” combines the words for “love” and “sibling.”38 It appears five times in the New Testament. Modern translations concerned to not misrepresent its gender inclusiveness sometimes translate it as “love” or “mutual love” (e.g., Rom 12:10, NIV and NET, respectively). But its connection to the family metaphor should not be missed. An alternative translation might be “family affection,” especially in contexts where the word “love” is also present. Christians should have the closeness and love for one another that characterize siblings (in their better moments):

Love one another with brotherly [and sisterly] affection. (Rom 12:10 ESV)

Now concerning love of the brothers and sisters, you do not need to have anyone write to you, for you yourselves have been taught by God to love one another. (1 Thess 4:9 NRSV)

Keep on loving one another as brothers and sisters. (Heb 13:1 NIV)

Having purified your souls by your obedience to the truth for a sincere brotherly [and sisterly] love, love one another earnestly from a pure heart. (1 Pet 1:22 ESV)

Make every effort to supplement your faith with goodness, goodness with knowledge, knowledge with self-control, self-control with endurance, endurance with godliness, godliness with brotherly [and sisterly] affection, and brotherly [and sisterly] affection with love. (2 Peter 1:5–7 HCSB)

Paul also connects love and brothers and sisters in his distinctive address: “My beloved brethren” (1 Cor 15:58; Phil 4:1 NASB), Greek adelphoi mou agapētoi. Likewise, John connects being brothers and sisters in Christ with the response of love:

Anyone who loves their brother and sister lives in the light. (1 John 2:10)

This is how we know who the children of God are and who the children of the devil are: Anyone who does not do what is right is not God’s child, nor is anyone who does not love their brother and sister. (1 John 3:10; see also 3:18; 4:20).

Psalm 133:1 gives us a glimpse of the background for such sentiments in the Old Testament: “How good and pleasant it is when brothers [and sisters] live together in harmony!” (Ps 133:1 HCSB).

Cognitive Meaning: Harmony, Mutual Care, and Support

If love and intimacy are the emotive effect of living out the metaphor of the family of God, what is this metaphor’s cognitive meaning? What does the New Testament say about the identity of believers as brothers and sisters? In general terms, two things stand out.

First, sibling language is used to call for avoiding conflict: “Is it so, that there is not among you one wise man who will be able to decide between his brethren, but brother goes to law with brother, and that before unbelievers?” (1 Cor 6:5–6 NASB). Brothers and sisters are not to squabble.

Second, being brothers and sisters is the grounds for exercising mutual care and support:

Brothers and sisters, if someone is caught in a sin, you who live by the Spirit should restore that person gently. But watch yourselves, or you also may be tempted. Carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ. (Gal 6:1–2)

“The sibling metaphor relates to social relations, to emotional ties, to harmony and concord, as well as to a common ancestry through the work of Christ, and so has a rich range of links to Christology, ecclesiology, ethics, and so on.”

Paul Trebilco39

Old Testament precedents include the ban on charging interest to fellow Israelites: “Do not charge your brother [or sister Israelite] interest on money, food, or anything that can earn interest. You may charge a foreigner interest, but you must not charge your brother [or sister Israelite] interest” (Deut 23:19–20 HCSB). Such language recalls Cain’s excuse that he was not his “brother’s keeper” (Gen 4:8–10). As brothers and sisters in Christ, we in fact are our brother’s and sister’s keepers.

SAMPLE TEXTS: HEBREWS AND THE SERMON ON THE MOUNT

To this point in this chapter, we have been looking broadly at the meaning of the metaphors of believers in Christ as God’s children and members of his family across a range of biblical texts. In order to demonstrate not only the breadth of the Bible’s treatment of such matters but also its depth, we shall take a look at two case study texts that serve to confirm and illustrate our findings: the letter to the Hebrews and the Sermon on the Mount.

Hebrews

The letter to the Hebrews is a case study of how the theme of believers as children of God flows from the truth that Jesus is God’s Son. The letter reminds us of the significance of the Son of God for our identity as children of God. As Amy L. B. Peeler puts it, in Hebrews “God’s paternal relationship with Jesus grants to the audience members their identity and hope as children of God.”40

Hebrews opens by focusing on God’s relationship to his Son: “In the past God spoke to our ancestors through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son” (Heb 1:1–2a). The first time that God speaks in the letter it is to his Son: “You are my Son; today I have become your Father” (1:5a). And as Peeler notes, “in God’s first explicit address to the author and his audience, God declares their status as his huioi [sons] (Heb 12:5–6).”41 Peeler also observes that there is a close similarity between God’s initial declaration of Jesus’s sonship in 1:5b (“I will be his Father, and he will be my Son”) and the new covenant promise issued to the community in Hebrews 8:10c (“I will be their God, and they will be my people”), which suggests their new identity as God’s children is based on God’s relationship to his Son.42

The letter in fact is infused with familial language. God as “Father” appears at two pivotal points. The first is in Hebrews 1:5 (quoting Ps 2:7) in reference to Jesus: “You are my Son; today I have become your Father.” The second is in Hebrews 12:9 (alluding to Isa 38:16) with reference to believers: “Moreover, we have all had human fathers who disciplined us and we respected them for it. How much more should we submit to the Father of spirits and live!” Correspondingly, Jesus in Hebrews is regularly referred to as the “Son” (Heb 1:2, 5, 8; 3:6; 4:14; 5:5, 8; 6:6; 7:3, 28; 10:29) and as God’s heir at his Father’s right hand (1:2, 4; 8:1; 10:12; 12:2) awaiting his inheritance (1:13). Likewise, the readers are described as God’s sons (Greek huioi, 2:10; 12:5–8) and God’s children (paidia; 2:13–14), and as members of God’s house (oikos; 3:6). They are also brothers and sisters (2:11–12; 3:1, 12; 10:19; 13:22) who endure training (paideia; 12:5–11) as they look forward to their own eternal inheritance (1:14; 6:17; 9:15; 11:40; 12:22–24, 28).

“God’s paternal relationship with Jesus his Son shapes the theology and Christology of the letter [of Hebrews], and, in so doing, constructs the identity of the audience, legitimizes their present experience, and supports them in their endurance. Because God is Father and Jesus is Son, the author argues, the audience can be confident in their status as God’s children and in the promised future that status entails.”

Amy L. B. Peeler43

What does Hebrews do with the familial metaphor as applied to believers in Christ? It offers a thoroughly theological account of all believers, both male and female, as children of God in connection with Jesus as the Son of God. Just as God perfected his Son through suffering and death and gave him an eternal inheritance, so too God’s children may endure hardship in the knowledge that they have a stake in that inheritance. The identification of believers with God’s Son shows us how to live since God disciplines us as his children. It also gives us a vibrant hope and confident assurance in times of difficulty.

The Sermon on the Mount

If part of the answer to the question of personal identity concerns our conduct and character, the Sermon on the Mount has much to say about what it means to be a follower of Jesus Christ.

In the Bible it is a truism that identity informs behavior. Who we are is meant to flow through to how we behave: the righteous behave righteously; the wicked, wickedly; the humble, humbly; the proud, haughtily; and so on. We must be careful not to read the Sermon simply as a list of commands. Its ethics grow out of character rooted in identity.

So what is the identity that is meant to fulfill the weighty commands and undertake the radical lifestyle enjoined in the Sermon on the Mount? Who is supposed to put away anger, violence, lust, hypocrisy, pride, greed, self-assertion, and self-preservation and to love their enemies, keep their promises, and to forgive freely?

Matthew 5:43–48 provides the answer:

You have heard that it was said, Love your neighbor and hate your enemy. But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father in heaven. For He causes His sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. For if you love those who love you, what reward will you have? Don’t even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers, what are you doing out of the ordinary? Don’t even the Gentiles do the same? Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect. (HCSB)44

The Sermon on the Mount is a description of what it means to be a child of God and behave accordingly.45

Matthew stands out among the Synoptic Gospels for its interest in the fatherhood of God, with God as Father mentioned forty-four times, compared to just four times in Mark and eighteen times in Luke. John’s Gospel, on the other hand, with its focus on the Father and the Son in God’s mission to save the world, refers to God as Father around one hundred and twenty times.

The Sermon on the Mount declares “what life is like when you belong to the new aeon of God. This is what sonship is like.”

Joachim Jeremias46

However, Matthew is unique among all four Gospels in its keen interest in God as the Father of believers. God as our Father occurs just once in Mark and John and four times in Luke, but it appears twenty-one times in Matthew. And what is significant for our purposes is the fact that as many as sixteen references to God as the Father of believers appear in the Sermon on the Mount.47 The Sermon on the Mount is about the disciples as children of God.

The final reference to God as Father in the Sermon on the Mount differs from the rest in that it is not about God as the Father of the disciples, but God as the Father of Jesus:

Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord,” will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven. (Matt 7:21)

In the Sermon, Jesus refers to God as “your Father” fifteen times before telling us that the same God is his Father also.

A comparison of John and Matthew on this score is intriguing. In John’s Gospel, many references to God as the Father of Jesus throughout the Gospel are followed by one climactic reference to God as the Father of believers also (John 20:17).48 In the Sermon on the Mount, many references to God as the Father of believers are followed by one climactic reference to God as the Father of Jesus (Matt 7:21). The point is the same in both Gospels, even if the narrative artistry moves in opposite directions: there is a close connection between God as the Father of Jesus and God as the Father of Jesus’s disciples.

Jesus is identified in Matthew 1:1 as “the son of David, the Son of Abraham,” and “Matthew devotes the first main part of his Gospel to the theme of the person of Jesus the Messiah.”49 Subsequently in the Gospel, Jesus is identified as Emmanuel, Messiah, King, Son of Man, and so on. But as Jack Dean Kingsbury observes, in Matthew “preeminently, Jesus is the Son of God.”50 Stephen George summarizes this focus in Matthew’s Gospel:

Matthew’s placement of the title “Son of God” in the Gospel reveals its significance for his understanding of Jesus. It occurs at key moments of conflict: in Jesus’s battle against evil forces (4:3, 6; 8:29); and in Jesus’s confrontation with the leaders of Israel (26:63; 27:43). Its use is concentrated in key episodes in the Gospel’s narrative. It is used three times in the baptismal pericope and temptation narrative (3:17; 4:3, 6), and four times in the Gospel’s climax, the passion narrative (26:63; 27:40, 43, 54), where it is laden with irony. It is used at a major crux in the plot at 6:16, where God reveals to Peter the true identity of Jesus (16:17). Of the Synoptic writers, who all relate Peter’s profession, Matthew uniquely includes the “Son of God” title. All this points to the significance of the title “Son of God” for understanding Matthew’s Christology and the Gospel as a whole.51

Space forbids a full investigation of Jesus as the Son of God in Matthew. Suffice to say that it goes well beyond noticing titles. But for our purposes, we should note in particular the fact that Jesus’s sonship is connected to Israel’s sonship. Matthew 2:14–15, for example, quotes Hosea 11:1 to explain the significance of Jesus’s escape from Herod’s wrath and sets up the theme that Jesus is the true Israel and embodies Israel’s calling:

So he got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt, where he stayed until the death of Herod. And so was fulfilled what the Lord had said through the prophet: “Out of Egypt I called my son.” (Matt 2:14–15)

All of this is vital to understanding the identity of Jesus’s disciples as children of God in the Sermon on the Mount. The close connection between the Son of God and his disciples as children of God extends to the lifestyle that the Sermon commends. Jesus embodies his own teaching in the Sermon on the Mount. This is underlined subtly at numerous points.

Jesus the Son of God is his own example when it comes to expounding the conduct and character of his disciples as children of God:

• If they are to mourn (Matt 5:4), we see Jesus mourning in 26:38.

• If they are to be meek (5:5), Jesus says, “I am meek” in 11:29.52

• If they are to “hunger and thirst for righteousness” (5:6; see also 5:10, 20; 6:1, 33), Jesus is a model of righteousness and fulfills all righteousness (3:15).

• If they are to show mercy (5:7), Jesus leads the way in showing mercy in 9:27–30; 15:22–28; 17:15–18; 20:30–34.

• If as sons of God they are to be peacemakers (5:9), Jesus comes to bring peace in 12:15–21 and 26:52.53

• If they can expect persecution (5:10–12), Jesus is persecuted to the point of death in chs. 26–27 (see esp. 26:67–68; 27:30).

• If they are to be “the light of the world” (5:14), in 4:16 “the people living in darkness have seen a great light” in Jesus.

• If they are to let their “light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (5:16), they glorify God because of what Jesus did in 9:5–8 and 15:31.

• If they are to pray, “Our Father in heaven . . . your will be done” (6:9–10), Jesus prays three times in the garden of Gethsemane, “My Father, if it is not possible for this cup to be taken away unless I drink it, may your will be done” (26:42; see also 26:39, 44).

As Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount states, the teacher must do what he teaches (5:19). Unlike the Pharisees, when it comes to his own teaching Jesus is no hypocrite (see also Matt 23). Indeed, if the disciples are to build their lives on the rock of Jesus’s teaching (7:24–25), confession of Jesus as the Son of the living God is the rock on which the church is built (16:18), and Jesus promises to be with his disciples in their task of teaching all that he has commanded them (28:19–20).

“The entire Sermon on the Mount is a proclamation of the will of God to men and women who are children, and who are permitted to pray to their Father because he is near to them and hears them.”

Ulrich Luz54

The impressive linguistic and conceptual correlation between the Sermon on the Mount and the presentation of Jesus in the Gospel points to the conclusion that, as Karl Barth put it, “the Commander . . . embodies the command.”55 Or as Helmut Thielicke states: The Sermon on the Mount “is inseparably bound up with Jesus Christ as the representative of the coming aeon. . . . It proclaims a love which has meaning only with reference to him.”56 Jesus calls his disciples to a vocation analogous to Israel, God’s children, but at the same time is himself the true Israel and perfect Son of God. And as we seek to obey the Sermon on the Mount, we do so in humble dependence upon and in imitation of him.

“Jesus Christ is the perfect image of God, and the image of God is being restored as we grow into our adopted identity.”

J. Todd Billings57

DIVINE ADOPTION AND PERSONAL IDENTITY

Who am I? Who are we? As believers in Christ we are children of God, loved by God and given full rights of inheritance as heirs of God and co-heirs with Christ. We are brothers and sisters in God’s family, with our big brother Jesus being the model to whom we conform, thereby taking on the family likeness. This identity leads to a host of implications for our conduct. We imitate our heavenly Father by walking in love, light, and wisdom, and we imitate his Son Jesus Christ by living lives of loving sacrifice and service to others. As brothers and sisters, we are to live in harmony and with care for and support of our spiritual siblings. And we expect God our Father’s loving discipline.

Our identity as God’s children and the character that goes along with it has a long backstory. It’s not as though divine adoption comes out of the blue. To recap from the earlier chapters of this book, if Adam was a rebellious son of God and suffered “death” as a result,58 Israel proved to be God’s wandering children, and David and his dynasty of kings were God’s often-disobedient sons. Only Jesus Christ was God’s perfect and well-pleasing Son; and all believers in Christ are children of God in him. Our new identity as God’s children by union with God’s Son is our true identity, since, being made in the image of God, we were made to be God’s children from the very beginning. In Christ, as those known by God as his children, we regain our true selves.

RELEVANT QUESTIONS

1. Do you experience “brotherly and sisterly” love rather than friendship at the church you belong to? If not, why not?

2. Is it easy for you to relate to the idea of sonship? Why does this chapter argue for its importance?

3. As believers we are adopted into a new family, as sons and daughters of God the Father. How do you feel about the fact that God as your Father knows you intimately and loves you deeply?

4. The Sermon on the Mount shows that ethics grow out of character rooted in identity, so who you are flows through to how you behave. Discuss.

1. Some question whether or not being a child of God is actually a metaphor. They argue that the primary reality is God’s family, after which human families are the reflection. However, we are better to take being a child of God as a spiritual reality that the Bible expounds in comparison to the more familiar concept of human families. As D. A. Carson notes, while there are “many instances in the Bible where sonship is entirely natural and biological . . . [divine] sonship is metaphoric” (NIV Zondervan Study Bible [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015], 2664). Even John Calvin, who understood “the relationship of the Father and the Son to be the root of all reality,” writes of God in relation to humanity as being “like a father.” Cited in Canlis, “The Fatherhood of God and Union with Christ in Calvin,” 403.

2. Paul Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 300.

3. Janet Martin Soskice, Metaphor and Religious Language (Oxford: Clarendon, 1987), 24–53.

4. Richard B. Hays, The Moral Vision of the New Testament: Community, Cross, New Creation, A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 300.

5. N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God, Christian Origins and the Question of God 1 (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1992), 40.

6. As Steven J. Kraftchick puts it, “Metaphor is not an isomorphic mapping of all relationships within one field to another, but a highlighting of some and suppression of others” (“A Necessary Detour: Paul’s Metaphorical Understanding of the Philippian Hymn,” Horizons in Biblical Theology 15.1 [1993]: 23).

7. See Brian S. Rosner, “ ‘Stronger than He?’: The Strength of 1 Corinthians 10:22b,” Tyndale Bulletin 43.1 (1992): 171–79.

8. J. I. Packer, Knowing God, 20th Anniversary ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 149.

9. See for example James M. Scott, Adoption as Sons of God, WUNT 2.48 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1992); Trevor J. Burke, Adopted into God’s Family: Exploring a Pauline Metaphor, ed. D. A. Carson, NSBT 22 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006); and Peter Balla, The Child-Parent Relationship in the New Testament and its Environment, WUNT 155 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003).

10. Canlis, “The Fatherhood of God and Union with Christ in Calvin,” 404.

11. William E. Brown, “Inheritance,” in Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology, ed. Walter A. Elwell, electronic ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996).

12. Carson, NIV Zondervan Study Bible, 2664. Even in our day, some surnames reflect this tradition: Baker, Smith, etc.

13. This section builds on Roy E. Ciampa, “Missio Dei and Imitatio Dei in Ephesians,” in New Testament Theology in Light of the Church’s Mission: Essays in Honor of I. Howard Marshall, ed. Jon C. Laansma, Grant Osborne, and Ray Van Neste (Bletchley, UK: Paternoster/Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2011), 238–42.

14. Graham A. Cole, He Who Gives Life: The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2007), 269–70. See also Rom 8:15: “The Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship.”

15. Ciampa, “Missio Dei and Imitatio Dei in Ephesians,” 239.

16. Ibid.

17. This is the source of the English word “peripatetic,” which is used for teachers and other occupations whose work moves between more than one school or college.

18. Ciampa, “Missio Dei and Imitatio Dei in Ephesians,” 240.

19. For a thorough study of this theme, see for example Richard A. Burridge, Imitating Jesus: An Inclusive Approach to New Testament Ethics (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

20. This section builds on Richard Gibson’s unpublished notes on Romans.

21. Leon Morris, The Epistle to the Romans (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 333. Emphasis original.

22. Michael B. Thompson, Clothed with Christ: The Example and Teaching of Jesus in Romans 12.1–15.13, Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 59 (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1991), 78–82.

23. Thompson, Clothed with Christ, 85.

24. See also Rom 3:24–25; 5:8–9; 8:3–4.

25. See also Prov 19:18; 29:17.

26. Richard A. Taylor and E. Ray Clendenen, Haggai, Malachi: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture, NAC 21A (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2004), 322–23.

27. Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament, 65. See also 300: “When early Christians called themselves ‘brothers and sisters’ . . . they were creating and shaping their identity and their ongoing life as well as reflecting their experience of what was significant for them.”

28. Trevor Burke, Family Matters: A Socio-Historical Study of Kinship Metaphors in 1 Thessalonians (London: T&T Clark, 2003), 174.

29. See many examples in 1 and 2 Macc and generally in rabbinic texts.

30. Abraham Malherbe, Paul and the Thessalonians: The Philosophic Tradition of Pastoral Care (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), 104.

31. Wayne A. Meeks, The Origins of Christian Morality: The First Two Centuries (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 5.

32. Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament, 65.

33. Thompson, Clothed with Christ, 27.

34. See Malherbe, Paul and the Thessalonians, 49: “It is generally agreed that the Christian concept of brotherhood developed out of Judaism. Pagans, in fact, took offense at the intimacy that Christians expressed with such language, and scorned it.”

35. See Matt 12:46–50.

36. Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament, 66.

37. Ibid., 65.

38. BDAG 1055.

39. Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament, 308.

40. Amy L. B. Peeler, You Are My Son: The Family of God in the Epistle to the Hebrews, The Library of New Testament Studies 486 (London: T&T Clark, 2014), 6, emphasis added.

41. Ibid., 3.

42. Ibid., 143. 43. Ibid., 8, emphasis added.

43. Ibid., 8, emphasis added.

44. NIV translates Matt 5:45 as “children of your Father in heaven,” taking huioi (sons) to refer to both genders.

45. This section is indebted to Stephen George’s excellent unpublished Moore Theological College fourth-year BD project, “The Contribution of the Sermon on the Mount to the Christology of the Gospel of Matthew” (2009).

46. Joachim Jeremias, The Sermon on the Mount (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1963), 161.

47. See Matt 5:16, 45, 48; 6:1, 4, 6 (2x), 8, 9, 14, 15, 18 (2x), 26, 32; 7:11. The six in the other three Gospels are Mark 11:25; Luke 6:36; 11:2; 12:30, 32; John 20:17. The five references outside the Sermon of the Mount in Matthew are in 10:20, 29; 13:43; 18:14; 23:9.

48. See the section on “Jesus and Mary Magdalene” in chapter seven.

49. Jack Dean Kingsbury, Matthew: Structure, Christology, Kingdom (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1975), 162.

50. Jack Dean Kingsbury, Matthew as Story, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1988), 57.

51. George, “The Contribution of the Sermon on the Mount to the Christology of the Gospel of Matthew,” 40–41. Note too the diverse characters in Matthew who profess Jesus as the Son of God. Opponents include: the tempter (4:3, 6); the demon-possessed man (8:29); the high priest (26:63); and those passing by (27:40). Supporters include: the heavenly voice (3:17; 17:5); disciples in the boat (14:33); Peter on behalf of the disciples (16:16); and the centurion (27:54).

52. In the New Testament Greek, praus, “meek,” only appears in Matt 5:5; 11:29 and 1 Peter 3:4. Also, Matt 11:28–30 is unique to Matthew in the Gospels.

53. However, Matt 10:34 indicates that this was not his only task: “Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword.”

54. Ulrich Luz, The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 49.

55. Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of God—Volume II, Part 2, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1957), 690.

56. Helmut Thielicke, Theological Ethics, Volume 1: Foundations (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969), 354.

57. J. Todd Billings, Union with Christ: Reframing Theology and Ministry for the Church (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2011), 33.

58. Cf. Deut 21:18–21 where a rebellious and disobedient son receives the most severe punishment.