CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE YARD IN THE FUTURE

The police of the future are often painted in quite a sinister light. When science fiction writers and filmmakers imagine the world to come, the law-enforcers are sometimes robots (Robocop); sometimes terrifying and authoritarian magistrates (Judge Dredd); or, in the case of one particular alien species featured in Doctor Who, space rhinos who act as judge, jury and executioner rolled into one. The real police in Scotland Yard, however, are mindful of concerns that technology is changing the way the law is upheld. There are certainly no plans to introduce space rhinos and, more than that, there is an active belief that no matter how advanced artificial intelligence and robotic innovations become, the principle of the Yard must continue to adhere to Sir Robert Peel’s 1829 motto: ‘The police are the people’.

Nonetheless, advances in technology have brought the science of detection forward in leaps and bounds. Cold cases of the past have been solved with innovative new technology, and current crimes, performed by the modern-day nifty criminal, are swiftly solved with the forensic analysis available to the force. And so, the puzzles in this section celebrate Scotland Yard in its new age, and task you with all the new challenges facing detectives. We’ll see conundrums involving computers and algorithms, and contend with puzzles concerning the power of informed prediction and remote-controlled cityscape surveillance.

Rather like their Victorian counterparts, today’s Scotland Yard officers understand that they are standing on the threshold of a completely new landscape–both socially and criminally. The spread of the internet, social media and online transactions are thought by some to constitute a new Industrial Revolution. It is certainly changing the way that criminal gangs operate, and also the scale of their operations, giving them a global access that they never had before. Gangs now have the chance to communicate on wholly encrypted devices, and cheap air travel means fast and easy movement anywhere on the planet. Computer-based frauds make nonsense of national borders. In the old days, crime at least required a physical presence. Now it can be committed remotely from thousands of miles away.

This is why science fiction writers have tended to imagine a police force that responds in kind: a constabulary of super-fast computer operators, able to tap into countless databases, and also able to get ahead by anticipating and parrying further electronic moves. These writers see a day when crimes can be solved before they are even committed. But the reality is much more complex, and more reassuring, than this. A recent conference of senior police personnel, some from Scotland Yard and others from forces around the world, discussed how new policing was to work without being too intrusive into general computer privacy, or too remote from the public on the streets. It was noted, for instance, that the future would see a greater use of drones: small flying devices that can film while nimbly flying through streets. This could pretty much fill the role currently carried out by police helicopters, but more efficiently. How better to track an offender unobtrusively than by sending one of these quiet flying automatons out to hover above with its unblinking eye? Drones have already proved extremely valuable in terms of carrying out searches. People and details that could be missed on foot are captured in high definition by cameras floating just a few feet above the ground.

The increasing use of this technology has raised important questions about what counts as public and private space, because drones see and record everything, not merely a suspect wandering about. They can see into back gardens, and in through doors and windows. Added to this, drones in the future could also be fitted with facial recognition software, which means that the police would have the power to watch and record the movements of everybody, offenders and innocent parties alike, as well as identify them. Because the police, and especially Scotland Yard, have always been sensitive to the idea of muscling in on the private space of the innocent, there is a strong need for the ethics to be debated, and safeguards discussed. In previous decades, the use of phone-tapping, in its day an innovation as useful as drones, caused all sorts of arguments, and Scotland Yard has always been intensely careful about its deployment, and about the rules under which it can be used.

One slightly unexpected development that has come from the computer age is that detectives now arguably have too much evidence. That is, the amount of information that is contained on the phones and computers of suspects is absurdly vast. In some cases, there are just simply not enough officers to be able to digest and analyse all of the data stored. But innovative steps have been taken and experiments carried out; not with humans, but with artificial intelligence, to see if a computer can analyse everything on a device from photos, to documents, to messages, to contacts, at a speed unimaginably faster than any human could manage. Facial recognition software could also alert officers to other gang members who show up in pictures. Again, there are a huge number of legal firepits to fall into here, including how to protect the public against being mistakenly identified by artificial intelligence and also the extent to which messages and closed social media postings can be burrowed into without violating all codes of privacy. But the exciting thing is the principle: for it also cannot be right that gangs get to take full advantage of an electronic world without Scotland Yard having electronic armoury with which to protect the public.

Slightly more troublingly, there are some police forces that are taking tentative steps towards prediction, as depicted in the dystopian science-fiction drama Minority Report. In that 2002 film, murders were ‘predicted’ by figures called ‘pre-cogs’ (as in pre-cognitive) and those who were envisaged committing the crime in the future were restrained (in the story, the knotty problem of predestination became a paradox: if someone is made aware of the future probability that they will kill, there is the chance they can ensure that they do not carry out the murder, thus eradicating that future and erasing the guilt, so the predicted murderers would be unjustly apprehended). There now exists a form of technology that uses algorithms to predict if an arrested person will offend again. As detectives from any era would recognise, this poses questions not merely about policing but indeed about the foundations of human nature.

If a computer can predict if we are ninety per cent likely to commit a crime, does this mean that there is no such thing as free will? Or worse, does this mean that there is next to no possibility of redemption? It also returns us to the age-old subject of whether a criminal brain is recognisably different from that of a non-offender. Where the Victorians believed in phrenology–the study of cranial bumps and nodules–the modern computer appears to envisage the criminal brain as a series of algorithms, suggesting that a criminal can simply be seen as a pre-programmed machine. Naturally, a great many people have recoiled with some force from this idea. And does it not make the very notion of policing itself redundant? To follow the argument to its natural conclusion: the computer spots and singles out the potential murderer; the potential murderer is arrested and, for his own good, as well as his potential victim, incarcerated. Result: no murders. But how could we ever punish people for crimes they have not actually committed? Ultimately, by allowing computers to decide the probabilities of human behaviour and potential, the most essential freedom is being stripped away from everybody; the chance to change course, the possibility of being a force for good rather than bad. Human brains are not algorithms. For if they were, what exactly would be the point of doing anything at all?

When senior personnel from Scotland Yard and elsewhere had their conference on the future of policing in 2018, there was a strong agreement that the human factor always had to be front and centre. Drones are all very well as all-seeing eyes, but you also need police officers on the streets. And while it is very useful to have a computer that can whizz through millions of texts, you still need human judgement to give all the messages proper context and interpretation. When it comes to the graver crimes, no amount of computer programming can replicate the work of an experienced detective in interviewing a killer and reassuring the wider community. More than this, no computer can ever unlock the secrets of a criminal’s heart. No amount of data analysis can explain the psychological knots that form motive, and there are still crimes behind closed doors–the theft of valuables, or chilling murders–which become complex labyrinths of human compulsion. So, in the immediate future it is highly unlikely that Scotland Yard will be deploying androids in blue uniforms to chase after miscreants at bionic speeds while shooting bright red laser bolts from their eyes.

Indeed, it is more likely that Scotland Yard’s future might look and feel a little like the enduring symbol of Britain’s greatest contribution to science fiction–the tardis. In Doctor Who, the eponymous Time Lord decided to disguise his miraculous space and time machine as a police box. These dark blue structures stood on London’s street corners from the late 1940s to the late 1960s. Their function was to act as a handy temporary holding cell for apprehended wrongdoers, as well as providing police with telephones to use in case of emergencies. A few years back, Scotland Yard decided to reintroduce and update the notion of the police box, with a model in Earls Court.

The telephone part of this box has been disused for a little while now, but the structure itself is still a perfect image for the Yard to project into our troubled present: quirky, unexpected, yet also understated and quietly dignified. And as with Doctor Who’s craft, it is a structure that conceals a range of potential hidden uses and innovation; until not long ago, it contained disguised CCTV cameras, (funding for the equipment dried up, so currently it is now more of an ornament). On the streets of Glasgow in Scotland, some remaining antique police boxes are treated as public sculptures. Speaking of which, the image of the police box was used a few years ago by the artist Mark Wallinger, who created one composed entirely of mirrored, reflective surfaces, giving a weirdly illusory sense that it was both there and not there at the same time. The point of the police box still remains though: a totem of reassurance that could conceivably contain a live constable having a crafty sit-down with a Thermos flask of tea. Like the revolving sign outside the Scotland Yard headquarters, the Earl’s Court police box is a tourist attraction. And it is difficult to imagine the apparatus of police forces in other parts of the world being greeted with such unalloyed affection and delight. One day, such a police box might indeed contain a robot constable. But the aim would always be to make the public feel safe, rather than to intimidate them.

And in this spirit, the puzzles in this section have a flavour of the futuristic: enigmas centred on electronic surveillance and data collection and analysis and lightning-fast leaps of logic…

BLUES IN TWOS

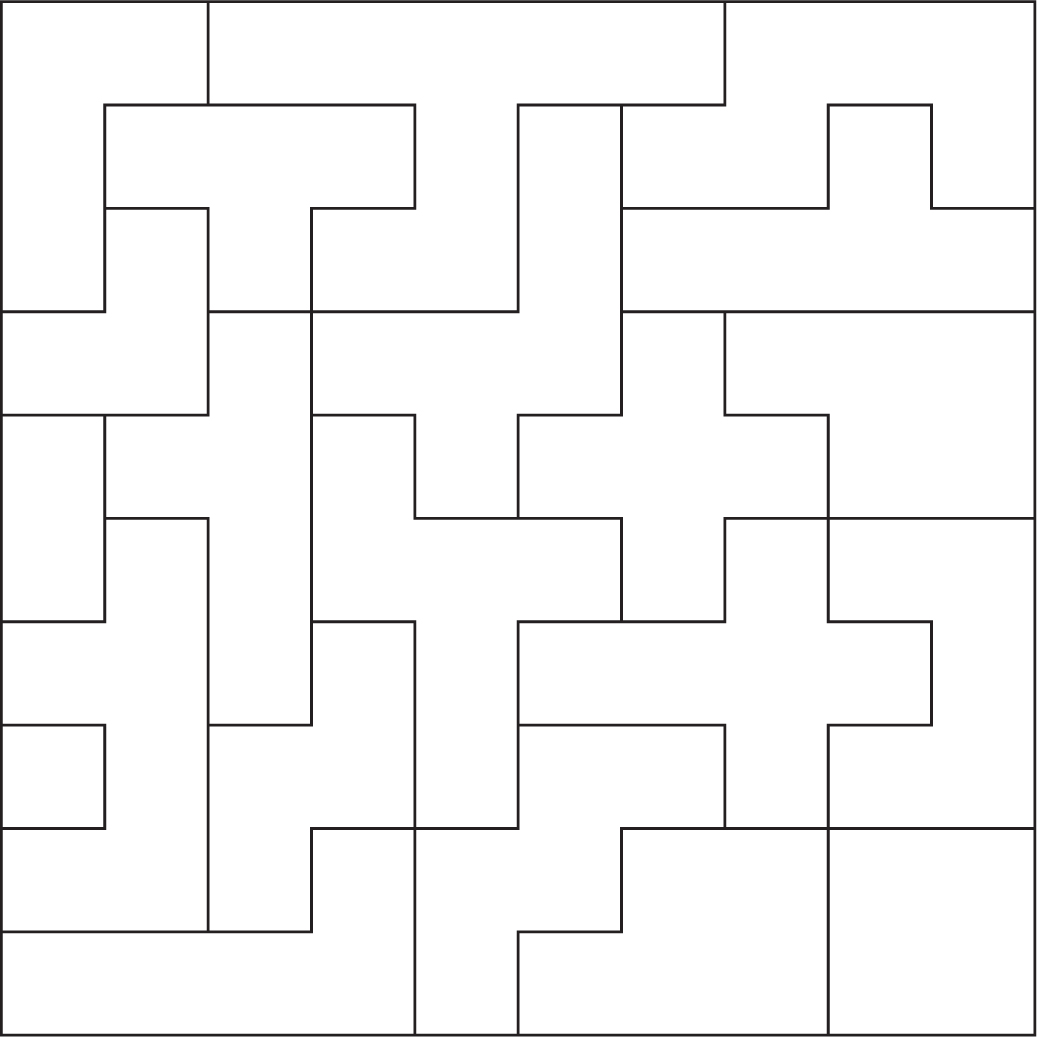

Whatever the future holds for policing, there is little doubt that the officers in blue will continue to patrol their beats in pairs. In this puzzle we ask you to look for pairs of a different type.

Complete the words below by adding the first two and the last two letters. In each separate case, the same two letters are needed and they must stay in the same order.

1 _ _ T I Q U A R I _ _

2 _ _ E E P I _ _

3 _ _ R M I N A _ _

4 _ _ E A D F A _ _

5 _ _ L I G H T _ _

6 _ _ P L A N A D _ _

7 _ _ E P S A _ _

8 _ _ I R T I E _ _

9 _ _ I G I N A T _ _

10 _ _ C A P T U _ _

FOLLOWING ORDERS

Orders must be followed. But what are the orders? There are instructions in this message that are clear for all who read it. There are also clues in the message to set you on your course to identify the NEXT meeting place. Where is it?

ORIGINAL MESSAGE READS:

Arrive at the station before twelve, noon. Be prepared for it to be busy, as people will be finishing their elevenses. Choose a quiet place to wait, this is often difficult to find. Don’t let on that you are a policeman, but of course you are renowned for your canniness. Everyone in the division has been informed and knows about the freight train and its cargo. Forget about all other matters even though it might be tricky. Go to greet the tall man in the green blazer in case he can’t identify you via some sixth sense. He will be wearing dark glasses, if I’ve had my orders followed to the letter. I advise remaining on the main platforms and one of our men will be waiting. Just be careful and take the right path, re-entering the station if needs be.

Where is your meeting place?

a) Marble Arch at 4 p.m.

b) Knightsbridge Underground at 5 p.m.

c) King’s Cross station at 2 p.m.

d) London Bridge at 3 p.m.

SWIPE CARD

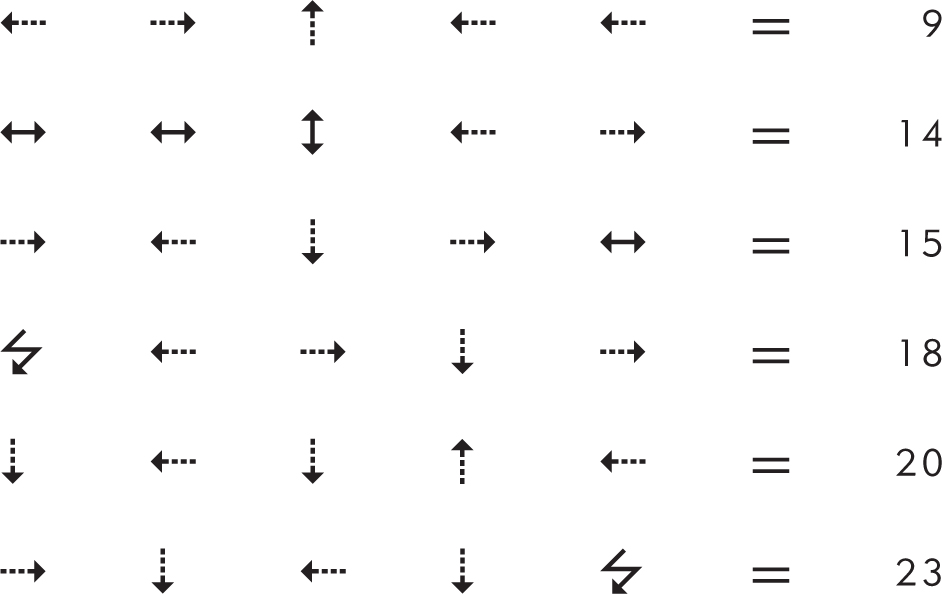

Look at the symbols on the swipe cards below, these indicate which hotel room number the key will open. There are SEVEN symbols in all, each represents a number between 1 and 7.

Which room number will swipe card  open?

open?

THE POWER OF OBSERVATION

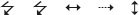

Technology has evolved beyond many people’s wildest dreams. Yet when you are dealing with people, observation is still key, making links is vital and remembering what you have seen is a powerful skill.

Look at the shapes below. You will see that they all look very different. However there are two shapes that are the same. Having seen one can you remember it and match it with the other?

DOWNLOAD THE APP

Look at the fragments of messages below. Clearly there are some words missing and the number of dashes in these words indicates the number of missing letters. If you need further assistance, all we can say is ‘download the app’!

1 In the theatre, the  was deafening as people

was deafening as people  their hands and stamped their feet. There was a wonderful

their hands and stamped their feet. There was a wonderful  between the performer and the audience. As the mystery figure

between the performer and the audience. As the mystery figure  the stage, the lights dimmed, and a

the stage, the lights dimmed, and a  sound was heard. No one would have willingly

sound was heard. No one would have willingly  seats at that chilling moment.

seats at that chilling moment.

2 The jewel raid  to be an open and shut case. The precious

to be an open and shut case. The precious  , carefully

, carefully  in a velvet bag,

in a velvet bag,  as if into thin air. Their owner had made an emotional

as if into thin air. Their owner had made an emotional  for their safe return. Maybe the robbery had left him

for their safe return. Maybe the robbery had left him  for cash. No one has as yet been

for cash. No one has as yet been  , and no one knows what will

, and no one knows what will  next.

next.

3 The young  was not at all

was not at all  (that rhymes!). He had completely lost his

(that rhymes!). He had completely lost his  , and was refusing food. Fruit, his usual favourite, whether it be traditional English

, and was refusing food. Fruit, his usual favourite, whether it be traditional English  , or tropical

, or tropical  , did not meet with his

, did not meet with his  , and he

, and he  at those who tried to tempt him. Perhaps a different

at those who tried to tempt him. Perhaps a different  was needed.

was needed.

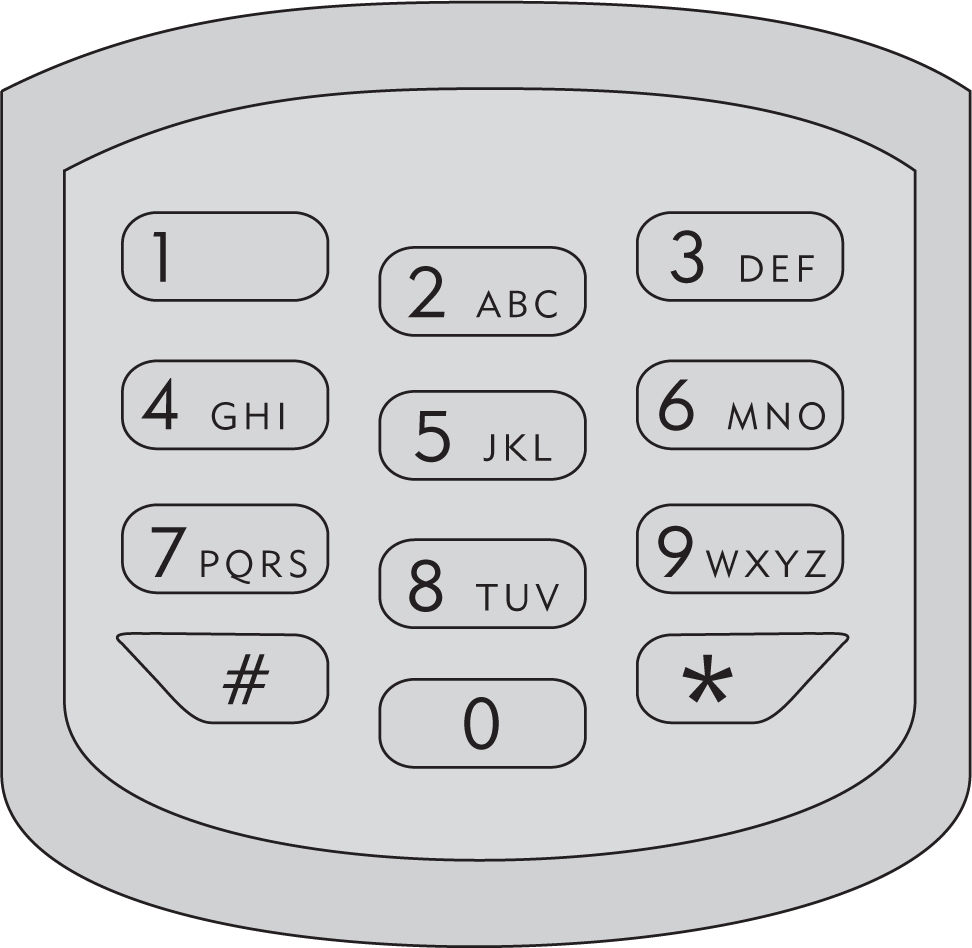

KEYPAD

The cyber criminal has tapped out a message regarding an important rendezvous. As you can see from the phone keypad each number can be any one of three or four letters. Using your powers of deduction and ingenuity, can you work out which letter is represented by each number, and therefore decode the message.

THE PERFECT PASSCODE

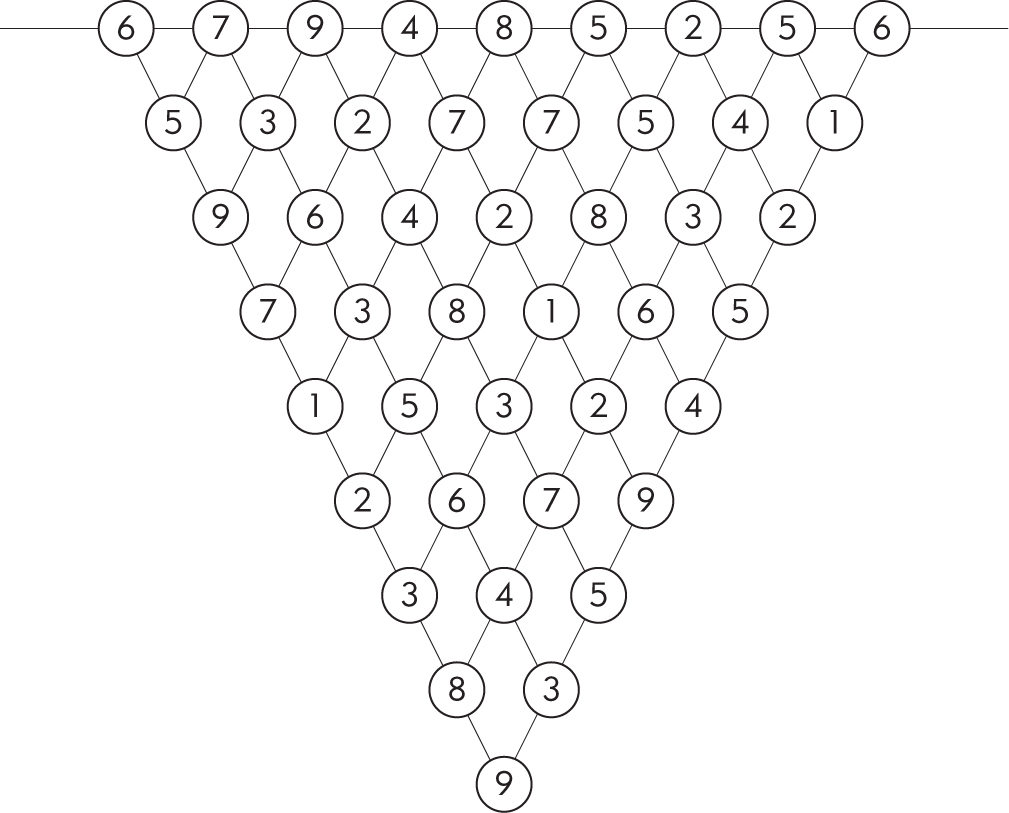

There are many ways of remembering passcodes, some more ingenious than others. Ruby Diamond had a fabulous jewellery collection. Most of it was kept in a safe with a nine-digit passcode, ending in a nine, which was quite difficult to remember. One day Ruby arrived at her favourite restaurant wearing a beautiful triangular-shaped necklace, which was admired by one and all. What those admirers didn’t know was that on the back of the necklace there were lots of numbers, which seemed to be written at random. But Ruby was no fool. She had created a unique way of remembering the passcode to her safe. It could be found by going from the wide end of the necklace to the narrow end, picking up a different number each time, on one level at a time, until the nine at the bottom was reached. All the numbers 1 to 9 were used.

What was Ruby’s perfect passcode?