THE WONDER OF WONDERS

He was a perfect wizard,” August Strindberg declared in a tribute to the author whose stories had enthralled him in his childhood. “The Steadfast Tin Soldier,” “The Snow Queen,” “The Tinder Box,” and other tales had drawn him into an enchanted world far superior to the drab realities of everyday life.1 Charles Dickens, Henry James, Hermann Hesse, W. H. Auden, and Thomas Mann—these are just a few of the writers who either grew up with Andersen’s stories, doting over them, or grew into them, admiring their imaginative force.

Today, we are rapidly losing sight of the sparkle and shimmer that Strindberg and others found in the tales of Hans Christian Andersen, the Danish writer who was born over two hundred years ago in the small town of Odense. We think of Andersen as the poet of compassion (“The Little Match Girl”), the enemy of hypocrisy (“The Emperor’s New Clothes”), or the prophet of hope (“The Ugly Duckling”). While there is no reason to challenge those assessments, we should not forget that Andersen does far more than parade vices and virtues before us. If his tales were only about sending messages and broadcasting morals, we would not still be reading him today.

And read him we do. UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, lists Andersen among the ten most widely translated authors in the world, along with Shakespeare and Karl Marx. Andersen’s stories have been part of bedtime reading rituals and school curricula in Beijing, Calcutta, Beirut, and Montreal. “The Snow Queen,” “The Ugly Duckling,” and “The Princess and the Pea” are not just story titles but terms with a kind of global currency. How many of us have grown up admiring the child in “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” identifying with the newborn swan in “The Ugly Duckling,” and weeping over “The Little Match Girl”?

Strindberg was exactly right to call Andersen a wizard, for there is something in his stories that transcends good and evil—something that we can, for want of a better term, call magic. That magic has nothing to do with ethics but has much to do with luck, good fortune, and chance. “The moral of every fairy tale,” as Adam Gopnik tells us, “is not ‘Virtue rewarded’ but ‘You never know’ (which bean will sprout, which son will triumph).”2 Fairy tales move in the subjunctive mode, presenting perils but also opening possibilities, telling us what could be and what might be rather than what should be. Along with what would seem to be mere randomness or serendipity also comes the reassurance that everything will, in the end, turn out all right.

We feel a catch of the breath when the Snow Queen’s carriage lifts off and flies through the air. Our hearts begin to pound when an evil witch turns boys into wild swans who soar over distant seas. And we thrill to the sight of ferocious dogs, eyes the size of teacups, guarding chambers containing untold wealth. But even that magic does not fully capture what is at stake in Andersen’s wizardry. Nor does it suffice to point to the mix of the wild and the weird, the charming and the brutal, the droll and the bloodcurdling in the stories, for those traits surface with predictable regularity in fairy tales from all cultures.

Hermann Hesse once hinted at what creates magic in Andersen’s tales when he recalled “the beautiful magic sparkle” of their “whole, multicolored, magnificent world.” Fairy tales like Andersen’s are invested above all in surfaces, in everything that glitters, dazzles, and shines. Still, they give us psychological depth, even when the characters themselves are described only in terms of appearances. Sadness is typically expressed as tears (sometimes made of crystal), and gratitude comes in the form of material objects (a miniature golden spinning wheel, a silver flute, or a dress of diamonds). As the stereotypical plots of fairy tales churn with melodramatic fervor, they also sparkle with surface beauty. The result is something I will call ignition power—the ability to inspire our powers of imagination so that we begin to see scenes described by nothing more than words on a page.3

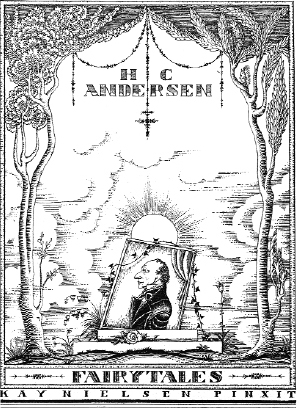

Kay Nielsen: Hans Christian Andersen

Committed to color, texture, light, brilliance, and clarity, Andersen’s fairy tales try to create the tangible beauty that they are, by virtue of their medium as mere words, powerless to capture. In “The Little Mermaid,” the sun looks like a “purple flower with light streaming from its calyx”; the eleven brothers in “The Wild Swans” write on “golden tablets with pencils of diamond”; and the soldier in “The Tinderbox” enters “a huge hall where hundreds of lamps were burning.” The bright wonders and vivid marvels that tumble fast and thick through the narratives go far toward explaining what drew artists like Rackham, Dulac, and Nielsen to Andersen’s stories, and their illustrations, as I discovered, when read with the text, can take your breath away.

The delicate description of Thumbelina’s cradle, with its mattress made of violets and its rose-petal blanket, produces something that, even if it remains invisible, is nonetheless wondrously exquisite. Andersen’s “The Goblin and the Grocer” (a tale little known outside Denmark) reveals just how powerfully words on a page can transform even a dark garret into a site of aesthetic pleasure. The goblin of the tale’s title peers into the room of a student, who is reading at his desk:

How extraordinarily bright it was in the room! A dazzling ray of light rose up from the book and transformed itself into a tree trunk that spread its branches over the student. Each leaf on the tree was a fresh green color, and every flower was the face of a beautiful maiden, some with dark, sparkling eyes, others with marvelous clear blue eyes. Every fruit on the tree was a shining star, and the room was filled with music and song.

J.R.R. Tolkien recognized the power of fairy-tale discourses and the “elvish craft” that produces other worlds from mere words. Storytelling in its “primary and most potent mode” draws on the magic of language to create Elsewheres, universes that form enchanted alternatives to the real world:

The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood we have already an enchanter’s power—upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our minds awakes.4

Step by step, word by word, Andersen, the “perfect magician,” mapped and named the objects in his other worlds.

In his college lectures on seven great novels—all “supreme fairy tales”—Vladimir Nabokov affirmed the power of language to construct other worlds of rarefied beauty.5 Like Andersen, Nabokov saw the supreme value of fiction in its power to create beauty through language. He considered it his duty as a writer to produce intellectual pleasure in the reader, who can observe the artist “build his castle of cards and watch the castle of cards become a castle of beautiful steel and glass.”6 Andersen would have understood the metaphor, for he too saw in the intersection of beauty and pleasure the supreme value of fiction. And that is why we still read him today.

We remember Andersen for the power of his images, for his castles of glass and steel. His paper cuttings, sketches, and collages remind us that he was supremely dedicated to the visual, a painter as much as a poet. C. S. Lewis once described how the Chronicles of Narnia were inspired by visual cues: “Everything began with images: a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion.”7 Drawn to the fairy tale because of “its brevity, its severe restraint on description, its flexible traditionalism, its inflexible hostility to all analysis, digression, reflections and ‘gas,’ ” Lewis instinctively recognized the importance of surface beauty and knew that he could depend on it to fuel the narrative engines of his multivolumed Chronicles. Like Andersen’s fairy tales, his fantasy narratives depend on the evocation of breathtakingly beautiful objects, figures, and landscapes.

If Andersen’s magic lies in the beauty of his tales, critics have been reluctant to call attention to it. They have, however, quite correctly described a poetics that mingles satire with sentiment, whimsy with tragedy, and passion with piety. And, above all, they have seen mirrored in the tales the maker of the tales. Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller, one of the most recent biographies of the writer, begins by declaring that its subject was a “compulsive autobiographer” and proceeds to document in superbly comprehensive ways how the art charts the stations of its author’s troubled soul. In the fairy tales, we discover, the truest self-portraits are etched in generous and fulsome detail. “He is the triumphant Ugly Duckling,” Jackie Wullschlager declares, “and the loyal Little Mermaid, the steadfast Tin Soldier and the king-loving Nightingale, the demonic Shadow, the depressive Fir Tree, the forlorn Little Matchgirl.”8

Reginald Spink, an earlier biographer, summarizes the collective critical wisdom of decades in his observations about the way in which Andersen’s fairy tales stage personal anxieties and desires and exorcise the demons haunting his imagination: “Andersen never stopped telling his own story. . . . Sometimes he tells it in an idealized form, sometimes with self-revelatory candor. In tale after tale—‘The Tinder Box,’ ‘Little Claus and Big Claus,’ ‘The Steadfast Tin Soldier,’ ‘The Swineherd,’ ‘The Ugly Duckling’—he is the hero who triumphs over poverty, persecution, and plain stupidity, and who sometimes, in a reversal of the facts, marries the princess (‘Clodpoll’) or scorns her (‘The Swineherd’).”9 In other words, either the stories square with the facts of Andersen’s life (in which case they are purely autobiographical) or they do not at all square with those facts (in which case they are still autobiographical).

Andersen was an expert in making paper cuttings, and some of his work is astonishingly intricate, mingling ballerinas with theater masks and death’s heads.

Swans and ballerinas figure frequently in Andersen’s paper cuttings, and this example offers an artful mingling of the two.

Andersen himself colluded with his critics in perpetuating the myth that the stories were all about him, but only partially. In The Fairy Tale of My Life, he reports that at school he told the boys “curious stories” in which he was always the “chief person.”10 In a letter of 1834 (written just before he published the fairy tales for which he became renowned), he suggests, however, that the characters in his works are not just self-portraits but portraits of those he encountered in real life: “Every character is taken from life; every one of them; not one of them is invented. I know and have known them all.”11 And finally, while writing about his growing enthusiasm for the genre of the fairy tale, Andersen suggested that he was relying on storytelling traditions, as much as on real life: “I gained confidence and was greatly motivated to develop in this direction and to pay greater attention to the rich source from which I had to create.”12 Clearly, it was not all about Andersen, and the author himself tells us as much.

As tempting as it may be to map direct connections between a story and its author or to think of the tales as mirrors of their author’s psyche, those moves invariably take us away from the tales themselves. The real risk of focusing too sharply on Andersen and on his anxieties and desires, his pathologies and perversities, or his aspirations and ideals is that, in the frenzy of looking for latent meanings, we lose the sense of wonder aroused by the manifest content of the tales. The Snow Queen’s crystal palace, the utopian realm of poetry discovered by the Shadow, the tin soldier’s dizzying voyage into the sea all lose their power to stir the senses under a barrage of biographical detail. The more we worry about the artist and his disorders, the less we care about the order of the art.

THE EMPEROR’S WONDROUS CLOTHES

Andersen’s great gift was to create magic through the fairy tale in the form of arresting beauty, captivating characters, and absorbing plots. The appeal of his stories is so enduring that many operate like the oral fairy tales to which he was so attached as a child, circulating by word of mouth, creating new versions of themselves, and migrating with ease from one culture to another. Many have become part of local wisdom and lore even as they have attained a kind of global standing.13

Andersen’s name is often mentioned in the same breath as Charles Perrault or the Brothers Grimm, the men who produced the landmark anthologies of folklore at the end of the seventeenth century in France and in the early nineteenth century in Germany. In that now renowned fairy-tale pantheon, Andersen, the son of a washerwoman and shoemaker, is the one who was closest to the common people and who actually grew up with the oral storytelling culture of the spinning room. Yet, ironically, he is also the one who is seen as the champion of the literary—as opposed to the traditional oral—fairy tale. Unlike the Brothers Grimm, Andersen did not reproduce what he heard from the lips of the people. Still his stories circulate just as broadly as those of Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. And the films based on them take in their share of revenue for Disney Studios. Despite their literary origins, Andersen’s tales have joined those of Perrault and the Grimms to become the foundational cultural stories and formative childhood plots of Western culture. They are our folklore.

“The Emperor’s New Clothes” (1837) is one of the best known of Andersen’s tales, and it is repeatedly described as a classic: “charming,” “beloved,” and “winning.” A recent illustrated retelling by a team of celebrities captures the story’s iconic status: “Hans Christian Andersen’s beloved tale of a king and his invisible clothes has delighted children the world over for generations. Now . . . an all-star cast of actors, celebrities, and award-winning illustrators has re-imagined the classic tale in this hilarious and sumptuously illustrated rendition. . . . The Emperor’s New Clothes is a charming book for the whole family to enjoy.”14 The only terms overlooked in this enthusiastic declaration of family-friendly values are “timeless,” “universal,” and “enchanting”—attributes often ascribed to cultural stories known the world over, for example, “Cinderella” and “Sleeping Beauty.”

More effectively than any of the other tales, “The Emperor’s New Clothes” established Andersen’s reputation as a man who created stories for children—not just in the sense of target audience, but also as beneficiaries of something extraordinary. The lesson embedded in it is so transparent that its title circulates in the form of proverbial wisdom about social hypocrisy. But more importantly, “The Emperor’s New Clothes” romanticizes children by investing them with the courage to challenge authority and to speak truth to power.

The plucky child who declares that the Emperor has no clothes is indeed “beloved.” A scientist working in the field of evolutionary biology borrowed the title of Andersen’s tale and praised its hero: “The honesty and naïveté of the child in Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale are sufficient to demonstrate the foolishness of the emperor and his public. The child is capable of honest observation and is willing to state the obvious.”15 “The Emperor’s New Clothes” contains an underlying fantasy about our cultural desire to unmask duplicity along with self-deception and to speak the truth, no matter how painfully humiliating it may be to those in authority—or perhaps especially because it will be painfully humiliating.

D. H. Lawrence urged readers to trust the tale rather than the teller, and I want to take a closer look at this particular tale to reach, if not the truth, then at least a sharper understanding of what really matters in plots that have repeatedly been read as morality plays or as allegories of Andersen’s personal sufferings and fixations. Jack Zipes, in a brilliantly irreverent biography of the Danish author as “misunderstood storyteller,” has suggested that “The Emperor’s New Clothes” enabled Andersen to discharge his hostility toward the aristocracy: “Andersen’s anger at a pretentious and indifferent upper class that lacked sensitivity for art, especially for his particular kind of art, had to be channeled in such a way that he would not become self-destructive.”16 Zipes destabilizes that reading when he asks: “Do we need deceivers to learn the truth about decadent and deceptive emperors? Or do we need childlike honesty?”17 If truth be told, the answers are not at all obvious. Is it possible that the two swindlers in the story are the real champions of truth, after all? Have we been deluding ourselves all along in thinking that the child is the heroic figure who exposes social hypocrisy and collective denial?

The Emperor may indeed have no clothes, but the fabrications of the swindlers—their acts of invention—are invested with a certain dramatic artfulness (they cut the air with scissors and sew with a needle that has no thread) and with a powerful degree of imaginative value (though one diametrically opposed to what is asserted by the thieves). Oddly, that “most wonderful cloth” that they produce becomes more and more substantial as it is described, and by the end of the tale the courtiers are engaging in pantomimes similar to those practiced by the swindlers while picking up the train and holding it in the air. Their art works magic, for it produces out of thin air something that is beautiful and seemingly palpable, even though it is not at all there.

Andersen’s weavers, as one commentator points out, are merely insisting that “the value of their labor be recognized apart from its material embodiment.”18 The invisible cloth they weave may never manifest itself in material terms, but the description of its beauty (“as light as spiderwebs” and “exquisite”) turns it into one of the many wondrous objects found in Andersen’s fairy tales. It is that cloth that captivates us, making us do the imaginative work of seeing something beautiful even when it has no material reality. Deeply resonant with meaning and of rare aesthetic beauty—even if they never become real—the cloth and other wondrous objets d’art have attained a certain degree of critical invisibility. Their value has been obscured by the lesson inscribed through the embodied finger-pointing (the sure sign of a message) at the end of the tale. It is no accident that nearly every illustration of the story shows us the child gleefully calling attention to the Emperor’s nakedness. When it comes to children’s literature, endings count, and it is there that we habitually—sometimes mindlessly—seek meaning and morals for the child reading the story. Aesthetics rarely matters, even if it is the appearance of beauty that has engaged attention in the first place. But it is to beauty that we must look to discover why we still read Andersen today.

MATCHES AND THEIR IGNITION POWER

The wondrous objects concealed in Andersen’s tales are not always easy to identify and locate, for they engage in remarkable disappearing acts, playing hide-and-seek with characters and readers alike. Take the case of the pea in the celebrated “Princess and the Pea,” and it becomes evident that even the most ordinary objects can come to be invested with a special aura. The pea that was placed under the mattresses becomes, by the end of the story, an authentic museum piece on display in the Royal Museum. That is, if it has not yet disappeared—“if no one has stolen it,” as Andersen emphasizes. The nightingale, in the story of that title, also comes and goes, singing its enchanting melodies when it pleases. The invisible cloth, the bird in the woods, and the pea have real impact on the child reading the story, for they carry an emotional charge far more powerful than the lessons that have been permanently emblazoned on the tales by well-meaning editors. William J. Bennett may insist that “The Little Match Girl” is a “simple, tragic story that stirs pity in every child’s heart,” but many child readers will be more moved by the girl’s beautiful visions than by her abject state.

There is good reason to be cautious about enshrining beauty as the supreme value of the fairy tale. Andersen’s cult of beauty is shadowed by a profound fear that the enchantments of beauty can turn demonic, evoking desires so powerful that they exceed the bounds of civilized society and turn into an indulgence that is both evil and dangerous. A deep ambivalence about beauty and pleasure becomes evident in “The Red Shoes,” a story that punishes a child’s quite natural curiosity and appetite for beauty. The young Karen is enamored of a princess’s shoes—“There’s nothing in the world like a pair of red shoes!”—and has a pair made by the local shoemaker: “They were beautiful!” But the magic of that beauty turns against Karen, taking possession of her feet, compelling her to dance endlessly, and punishing her for desires that are, on one level, innocent, natural, and benign.19 One picture-book version of “The Red Shoes” eliminates the gory scene in which Karen’s feet are chopped off and ends happily with Karen vowing to “think twice” before she makes another wish.20

Beneath this simple story we can hear the rustling of ancient myths. It is as if Andersen had miniaturized and domesticated the rivalry between Arachne and Athena, creating a homespun tale in which a girl vies with a royal superior and is punished for daring to put beauty on display. But Andersen mingles the pious with the pagan. As a devout if not wholly orthodox Lutheran, he had good reason to feel anxious about beauty and its sensual, seductive powers. The desire it arouses can never be wholly innocent, even when, as in “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” it has no substance at all. Beauty can quickly turn into a force with the power to devastate, crush, and overwhelm, especially in Andersen’s later tales about troubled artists and their struggles with the creative process.

But Andersen also understood that, without beauty, our lives are impoverished, and almost every story he wrote contains scenes, objects, or characters that are uplifting, stirring, and enchanting. Many begin with descriptions of landscapes that are “lovely,” and it is no accident that dejligt (the Danish term that captures a mix of beauty, charm, and delight) turns out to be Andersen’s favorite word. Andersen was dismayed that his critics took to counting the number of times the word appeared in a story.

Andersen’s cult of beauty may be unwelcome news to parents and educators (especially those who seek to enlist the stories in building character), but it would have been cheering news to one writer who took up the genre of the fairy tale and reworked it in literary terms. Oscar Wilde, whose literary fairy tales celebrate compassion and good works (sometimes even at the expense of beauty), ventriloquizes through a character in The Picture of Dorian Gray a view that captures the aesthetics of Andersen’s fairy tales: “People say sometimes that Beauty is only superficial. That may be so. But at least it is not so superficial as Thought is. To me, Beauty is the wonder of wonders. It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.”21 Appearances always count, and Andersen’s deepest commitment in the fairy tales is to the description of surface beauty.

It is not always easy to predict the “wonder of wonders” that will catch the attention of a child. For readers of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, it may be the Turkish delight that Edmund is given by the witch of Narnia. Francis Spufford, whose stirring memoir about childhood reading reveals the importance of reading with the spine (rather than the brain), does not specifically refer to Turkish delight, but he calls attention to C. S. Lewis’s ability to construct something that he calls “invented objects for my longing.” In The Child That Books Built, he reports that the author of The Chronicles of Narnia “gave forms to my longing that I would never have thought of, and yet they seemed exactly right: he had anticipated what would delight me with an almost unearthly intimacy.”22

Objects of desire appear in forms that are both obvious and subtle. For readers of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, it may be the Golden Ticket itself as much as the outlandish confections at the chocolate factory that serves as the “invented object” incarnating childhood desires. In Alice in Wonderland, if you look closely, it is not the White Rabbit but the watch in the waistcoat pocket that makes Alice “burn with curiosity.” All these invented objects produce a form of desire that serves as a reliable antidote to the boredom that can beset a child—sometimes the child in the book, sometimes the child outside the book, and sometimes both—with nothing to do.

Andersen is not often associated with beauty, in large part because Christian symbols and pious thoughts so dominate the narrative landscape of his fairy tales. “The Little Match Girl,” for example, is nearly always read as a story of salvation, without reference to the visions produced by the lighting of matches. The flames lit by the girl have the power to kindle imagination, producing visions of warmth (a brass stove), whimsy (a roast goose that waddles on the floor with a fork and knife in its back), and beauty (the Christmas tree). The comparison of the match’s glow to a “tiny lamp” is more than likely an allusion to the magic lamp in the story of Aladdin, a figure with whom Andersen identified when he read The Arabian Nights as a boy with his father. To the best of my knowledge, only Clarissa Pinkola Estés, in her compelling study of fairy tales, has understood the lighting of matches in poetic terms, and she equates the gesture with a damaging form of escapist fantasy: The little match girl loses herself in a vision “that has nothing to do with reality. It has to do with feeling nothing can be done, so one might as well sink into idle fantasy.”23

For Andersen, the light of poetry was more than idle fantasy. The little match girl can be seen as possessing a power of imagination not unlike that of Andersen’s “new Aladdin,” who promises to renew poetry with the illuminating power of his lamp:

A bard will come, who, with a child’s mind, like a new Aladdin, will enter the cavern of science—with a child’s mind, we say, or else the powerful spirits of natural strength would seize him and make him their servant—while he, with the lamp of poetry, which is, and always will be, the human heart, stands as a ruler, and brings forth wonderful fruits from the gloomy passages, and has strength to build poetry’s new palace, created in one night by attendant spirits.24

It is through beauty, poetry, and visionary power that the world will be renewed.

BEAUTY, REFLECTION, AND REPRESENTATION

Andersen revels in descriptions that evoke nature’s beauty. Here is the beginning of “The Little Mermaid”: “Far out at sea, the water is as blue as the petals of the prettiest cornflower and as clear as the purest glass.” “The Ugly Duckling” may state in its title the antithesis of beauty, but it begins by describing the vibrant colors of country splendors: “It was so beautiful out in the country—it was summertime! The grain was golden, the oats were green, and hay was piled in tall stacks down in the green meadows.” Andersen works hard to capture in words the physical beauty of earth, sea, and sky, and of the creatures that inhabit those three regions.

Beauty, as Elaine Scarry has eloquently put it, “seems to incite, even to require, the act of replication.”25 It brings “copies of itself into being,” and “when the eye sees someone beautiful, the whole body wants to reproduce the person.” This form of expressive desire is accomplished in its most immediate and unmediated manner by what is probably the most famous of all Andersen’s fairy-tale characters: the ugly duckling. Andersen’s barnyard animal experiences the shock of beauty when he sees swans, mourns their loss, and ends by metamorphosing into the very creatures that enchanted him.

The transformation does not take place without a price, and, for Andersen, the cost for creating beauty is almost inevitably some form of suffering. The ugly duckling begins as one of the most abject of Andersen’s characters, a creature that figures as the “laughingstock of the barnyard.” An outcast in the animal world, he is scorned by humans as well—kicked by the maid, shot at by hunters, and struck with tongs. “It’s because I’m so ugly,” the duckling declares, pointing to the disruptive energy of ugliness and its capacity to elicit hatred and aggression. The ugly duckling knows beauty and has seen it in the form of “majestic birds” with “magnificent wings” and “wondrous cries.” Although not driven by ambition (“How could he ever aspire to their beauty?”), he nonetheless performs as a supremely able imitator, one who comes to embody, not just replicate or duplicate, the beauty that fills him with awe and admiration.

The ugly duckling may suffer through the icy winter, but the transformation from duckling to swan requires no real effort on his part. It is, of course, part of a natural, biological process, much like the metamorphosis from caterpillar to butterfly. In the scene of transformation, the ugly duckling engages in a moment of reflection—reflection in the double sense of the term. He sees himself in the mirrored surface of the water and at the same time reflects on his condition. In this extraordinary humanizing moment—animals cannot, of course, engage in this double process—the ugly duckling transcends both ugliness and his animal condition. Reflection may not be the cause of the transformation, but it is telling that it coincides with the moment of transformation.

The process of creating beauty is not always so smooth, and, like beauty itself, it too has a dark side. “The Snow Queen” troubles the waters of “The Ugly Duckling,” suggesting that the desire to strive for beauty, when it falls short of perfect imitation, can turn diabolical and destructive. Andersen’s story of Kai and Gerda makes it clear that creativity can turn sinister, for it is affiliated with a disturbing form of self-division and self-deception. The magic mirror introduced in the very first paragraph of “The Snow Queen” is a tool of the devil, a surface that has the capacity to shrink what is “good and beautiful” and to enlarge what is “worthless and ugly.” It may reflect reality but it also distorts it, engaging in critical disfigurement that is said to show “what people and the world were really like.”

Andersen’s troll/devil is a kind of artistic anti-Christ whose art consists of finding truth through satiric distortion. In the course of his arrogant, Babel-like project to take the glass up to the heavens, he creates shards that lodge in the eyes and hearts of all those down on earth, including Kai, who is seduced by the icy beauty of the Snow Queen. Kai is, in the end, redeemed by the warm, passionate tears of his beloved Gerda, but not before he almost loses himself in the frigid palace of the Snow Queen, working an ice puzzle of the mind, trying to shape frozen chunks into the word “Eternity.”

In “The Ugly Duckling,” we have a triumphant moment of self-reflexivity, for the transformed duckling, unlike Narcissus, does not fall in love with his image. He recognizes that what is being mirrored back to him is his own reflection. Consider Kai, however, who labors in solitude, mirror lodged in his heart, to achieve immortality. He is caught in a conflict that one critic has called the “nemesis of mimesis,” the revenge of art on those who try to represent and create.26 Striving for mathematical perfection and rarefied beauty, Kai remains trapped in narcissistic self-absorption, struggling with the Snow Queen’s ice puzzle, which, when solved, will reward him, not only with the whole world and a pair of ice skates, but also with immortality. And yet “everything ends up in the trash,” as we learn in “Auntie Toothache,” Andersen’s most astonishingly dark anti–fairy tale. Works of art may outlive their creators, but the notion of “immortality” for artists and for their creations is nothing but a cultural lie. Even works of art are doomed to decay and crumble.

ANIMATING ART

Andersen is deeply committed to art, but at the same time he recognizes the dangers of a cold, austere cult of beauty that, in its quest for immortality, endangers the artist’s soul. These are grown-up matters, and the second installment of fairy tales in this collection was meant for adult audiences willing to follow the writer’s struggle to define exactly what is at stake in artistic creation. These “high-voltage” narratives map a deeply personal poetics that complicates the straightforward aesthetics of fairy tales like “The Ugly Duckling.”27 I will turn to two tales—“The Psyche” and “The Shadow”—to deepen our understanding of questions that troubled Andersen far more profoundly than the more prominent fairy tales let on. These are stories that need to be resurrected and put in dialogue with the earlier tales if we are to understand how devotion to beauty raises a legion of devilish ethical questions.

A beautiful work of art occupies the central position of “The Psyche.” Written in 1861, the story engages in its title the thematic nexus found in so many of Andersen’s fairy tales: beauty, spirituality, and transformation. Psyche, the legendary beauty who marries Cupid and breaks the taboo of looking at him, bears the Greek name for “soul” and is endowed by the gods with immortality. She is only one of many mythological figures invoked by the text, which reworks the Pygmalion story and also draws on the figure of Medusa to work out its narrative terms. As in many of Andersen’s tales, the pagan (Greek, Roman, and Nordic mythologies) informs the narrative in unexpected ways and bumps up against the overlay of religious themes.

The wondrous invented object in “The Psyche” takes the form of a marble statue sculpted by an unnamed perfectionist who destroys everything he creates until he achieves flawless beauty. Inspired by a young woman he sees in a garden, he molds a statue, not just of the young woman but also of an image familiar to him from his studies of art, Raphael’s Psyche. “He had never seen such a beautiful woman before. Yes, once! He had seen one painted by Raphael, painted as Psyche, in one of Rome’s palaces. Yes, her portrait was there—and here she was alive!”

When the young Roman woman sees the artist’s statue and hears his passionate declaration of love for her, she turns on him. In that instant, “the face of beauty bore a resemblance to that petrifying face with serpent hair.” Repeating the sculptor’s act of turning a person into an image of stone, she transforms herself from Psyche to Medusa. Pygmalion may have brought his statue to life, but here the statue’s model saps life from the artist. However much the artist’s masterpiece may succeed as a work of art, it turns on him in ways so powerful that he abandons art, hoping to find salvation in monastic life.

The artist never makes a name for himself, but his work of art is unearthed long after his death and acquires immortality: “He was gone now, scattered abroad as dust is destined to be. But Psyche—the fruit of his most noble labors and the glorious work that betokened the spark of the divine in him—remained, and she would never die.” The artwork effaces the artist, leaving him to molder while it gets its revenge as an admired, acclaimed, shining exemplar of beauty.

As in “The Ugly Duckling” and “The Snow Queen,” an aesthetics of whiteness dominates “The Psyche.” The blinding white beauty of the marble statue, “carved from snow,” like Kai’s letters, can be seen as what Toni Morrison, in a study that identifies the racial fault lines in black/white aesthetics, has called an “antidote for and meditation on the shadow that is companion to this whiteness.”28 Just as beauty is haunted by death even as it lays claim to immortality, white is troubled by blackness, by shadows and darkness that are a source of both fear and desire. It therefore comes as no surprise to find that Andersen had written, some fifteen years before he penned “The Psyche,” a story called “The Shadow.” And it is perhaps not coincidental that the Danish titles (“Psychen” and “Skyggen”) come close to rhyming with each other.29

“The Shadow” is itself haunted by the anxiety of influence. When its protagonist, a “learned man,” loses his shadow, he is less disturbed by the disappearance of the shadow than by the fact that “there was another story about a man without a shadow.” “The Shadow” is mirrored by another tale: Adelbert von Chamisso’s Romantic novella Peter Schlemihl’s Marvelous Story (1814), which was quickly translated from German into many European languages, including Danish. It had established itself as a classic by the time Andersen read it. The learned man, discouraged by the notion that others will believe that he is doing nothing but imitating a literary character, decides not to tell his story at all. In a grotesque inversion of a fairy-tale ending, he is liquidated on the wedding day of his shadow, who has come to life by imitating him.

How does the shadow disengage from his proprietor to lead an independent existence? Like so many of Andersen’s characters, he finds in beauty a power so seductive that it leads him to abandon his ordinary existence. One evening the learned man awakens to see “a strange glow” coming from his neighbor’s balcony, where flowers gleam like flames of the loveliest colors. There he sees an “enchanting” maiden and is nearly blinded. Light quickly gives way to sound, and the learned man finds himself under the “spell” of gentle and lovely music.

The house across the way is described as some kind of magic world (en Trolddom). The scholar turns his back on it and retreats to his study, where he devotes himself to the good, the true, and the beautiful. The shadow, by contrast, stretches himself and crosses over into the realm of poetry, exposing himself to the transformative power of art. There, he finds the means for attaining autonomy, creating illusions, and reversing the power relations between himself and his host. The shadow’s strategic alliance with beauty marks the triumph of double-dealing, duplicity, and fraud.

Andersen created in “The Shadow” a shadow of himself, a creature that feeds off his artistry but also lives on even after his creator has perished. If Andersen celebrated beauty and its transformative power in tales such as “The Ugly Duckling,” he also began to explore the sinister side to beauty—its links to artifice, frigidity, and paralysis—in works ranging from “The Emperor’s New Clothes” through “The Snow Queen” to “The Psyche.” “The Shadow” is his supreme concession to the troubled and troubling side to beauty, a dark exploration of how beauty may not in fact engage the good, the true, and the beautiful and may instead conceal a deadly desire to destroy as it takes over life, becoming animated and, at times, even achieving immortality.

Beauty may have a beastly side, but it never loses its power to weave spells that draw us into its alluring orbit. And Andersen summons it for us again and again, as if to remind us that, through its jolts and shimmers, it still has the power to animate us. Great writers, as Nabokov reminded us, are not only storytellers and teachers but also enchanters. The storyteller produces somatic effects, speeding up our beating hearts, leaving us breathless, making us weep real tears, or prompting us to laugh. The great teachers are beyond Aesop, instructing us less in the art of problem-solving than in the art of identifying and deepening them. The enchanters—along with the effects of the spells they work—are less easy to describe, but how they work their magic becomes utterly clear when we read the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen.

1. August Strindberg. “H. C. Andersen. Till Andersen-jubileet 2 april 1905,” in Efterslåtter: Berättelser. Dikter. Artiklar, ed. John Landquist, Samlade skrifter av August Strindberg 54, Supplementdel 1 (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 1920), 443–45. I am grateful to my colleague Stephen Mitchell for the translation of Strindberg’s remarks about Andersen.

2. Adam Gopnik, “Magic Kingdoms: What Is a Fairy Tale Anyway?” The New Yorker, December 9, 2002, 139.

3. The phrase is inspired by Elaine Scarry’s concept of radiant ignition as developed and elaborated in Dreaming by the Book (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1999).

4. J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” in The Tolkien Reader (New York: Ballantine, 1966), 22.

5. Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature, ed. Fredson Bowers (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 2.

6. Ibid., 6.

7. C. S. Lewis, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to Be Said,” in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories (New York: Harcourt, 1994), 36.

8. Jackie Wullschlager, Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller (New York: Knopf, 2000), 3.

9. Reginald Spink, Hans Christian Andersen: The Man and His Work, 3rd ed. (Copenhagen: Høst, 1981), 10.

10. Hans Christian Andersen, The Fairy Tale of My Life: An Autobiography (New York: Paddington Press, 1975), 21.

11. Wullschlager, Hans Christian Andersen, 3.

12. Hans Christian Andersen, Das Märchen meines Lebens ohne Dichtung, trans. Michael Birkenbihl (Frankfurt a.M.: Insel, 1979), 145–46.

13. Jackie Wullschlager refers to Andersen’s double gift of adapting and inventing: “He was the first writer who was not only skilled at adapting existing stories in an original and lasting manner, he was also capable of creating new tales that entered the collective consciousness with the same mythic power as the ancient, anonymous ones. This individual achievement has never been matched. Almost two centuries after he wrote them, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ and ‘The Ugly Duckling’ are still bywords for elements of the human condition, while his Snow Queen, Little Mermaid, and Steadfast Tin Soldier belong with characters of folk memory” (Introduction, in Hans Christian Andersen: Fairy Tales [New York: Viking, 2004], xvi).

14. Hans Christian Andersen, The Emperor’s New Clothes: An All-Star Retelling of the Classic Fairy Tale (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1998).

15. Joseph L. Graves, The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium (Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press, 2001), 1.

16. Jack Zipes, Hans Christian Andersen: The Misunderstood Storyteller (New York: Routledge, 2005), 127–28.

17. Ibid., 129.

18. Hollis Robbins, “The Emperor’s New Critique,” New Literary History 34 (2004): 663.

19. Zipes points out that the red shoes “are magical like our appetites, for they cannot be tamed on this earth, and Karen’s obsessive appetite reveals the injustices and mortifying humiliation that any child from the lower classes must suffer for desiring to improve his or her lot. Though she is punished for her fetish, the harsh punishment does not fit the crime, and one must wonder why a girl’s innocent longing for some beauty in her life is considered a sin” (Hans Christian Andersen, 88–89).

20. Barbara Bazilion, illus., The Red Shoes (Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge Publishing, 1997).

21. Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (New York: Random House/Modern Library, 1992), 25.

22. Francis Spufford, The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading (Holt/Metropolitan Books, 2002), 87.

23. Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype (New York: Ballantine, 1992), 322.

24. Jacob Bøggild, “Ruinous Reflections: On H. C. Andersen’s Ambiguous Position between Romanticism and Modernism,” in H. C. Andersen: Old Problems and New Readings, ed. Steven P. Sondrup (Odense: Univ. of Southern Denmark Press, 2004), 85.

25. Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2001), 3.

26. Karin Sanders, “Nemesis of Mimesis: The Problem of Representation in H. C. Andersen’s Psychen,” Scandinavian Studies 64 (1992): 1–25.

27. Jack Zipes focuses on Andersen’s “discourse of rage and revenge,” but he too recognizes that Andersen’s tales are also “theoretical speculations about the nature and beauty of art and the qualities a great artist needs to gain the recognition he deserves” (Zipes, Hans Christian Andersen, xv). Jackie Wullschlager describes these tales as “high-voltage,” for they take up “the terror of psychological disintegration” and other existential matters. See Introduction, Hans Christian Andersen: Fairy Tales, trans. Tiina Nunnally (New York: Viking, 2005), p. xvii.

28. Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1992), 33.

29. Bøggild, “Ruinous Reflections,” 94.