Prinsessen paa ærten

Andersen claimed to have heard this story as a child, and it is likely that he was inspired by a version akin to the Swedish “Princess Who Lay on Seven Peas.” The heroine of that tale is an orphaned child who sets out into the world accompanied by a pet cat or dog and who presents herself as a princess. Challenged by a suspicious queen, the girl’s royal ancestry is put to the test at night, when a small object (a bean, a pea, or a straw) is slipped under her mattress. Informed by the cat or the dog about the object, the girl complains about her inability to sleep and is declared to be of royal blood. The folktale heroine uses deceit to raise her social rank, but Andersen’s princess is the “real” thing and does not have to misrepresent her sensitivity.

For Andersen, a story demonstrating that “true” nobility resides in sensitivity rather than birth had a certain appeal. Constantly reminded of his lowly social origins by his many benefactors as well as by friends and critics, Andersen compensated by developing narratives demonstrating that those who are born in barnyards (the ugly duckling) or those who appear out of nowhere at the doorstep of royals (the princess) may turn out to be the real thing. As a poet, he aspired to become Denmark’s representative among a European elite of writers and thinkers. In “The Nightingale,” Andersen once again took up the distinction between the real thing and sorry imitators.

The 1959 musical Once Upon a Mattress, starring Carol Burnett as the irrepressible princess Winnifred the Woebegone, enjoyed success on Broadway for many years and was revived in 1997 with Sarah Jessica Parker in the lead role. There have been numerous cinematic adaptations, and the story has been rewritten creatively by Jon Scieszka as “The Princess and the Bowling Ball.”

“The Princess and the Pea” remains a favorite among Andersen tales, and the princess herself has become an emblem of supremely delicate sensibilities. The casual, conversational tone and humorous touches, which operate to produce parody, redeem many features that might offend modern sensibilities. The prince’s insistence on finding a “true” princess and the characterization of sensitivity as the exclusive privilege of nobility challenge our own cultural values about character and social worth. And yet the sensitivity of the princess can also be read on a metaphorical level as a measure of the depth of her feeling and compassion. Andersen also gives us a feisty heroine, one who defies the elements and shows up on the doorstep of a prince, whom she has succeeded in tracking down on her own.

Once upon a time, there was a prince. He wanted to marry a princess, but she would have to be a true princess. And he traveled all over the world in search of one,2 but something was always wrong. There were plenty of princesses around, but the prince could never be quite certain that they were real princesses. No matter what, something was always not exactly right. And so he would return home feeling sad, for his heart was set on marrying a real princess. One evening a terrible storm broke out.3 Lightning flashed, thunder roared, and rain came down in buckets—it was really dreadful! There was a sudden knock at the city gate, and the old king himself went to open it.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The prince takes his time scrutinizing the various young women masquerading as princesses. His robe has floral designs on it but also displays a dragon. One defiant toddler seats herself on the robes of the prince, who has his back turned to us as he contemplates the surprisingly youthful candidates for marriage.

It was a princess, and she was waiting outdoors.4 But goodness gracious! What a sight she was from all the rain and the nasty weather! Water was dripping from her hair and her clothes. It flowed in through the tips of her shoes and back out again through the heels. And she said that she was a real princess.

“Well, we shall see about that soon enough!” the old queen thought. She didn’t say a word, but went straight to the bedroom, removed all the bedclothes, and placed a pea on the bottom of the bed. Then she took twenty mattresses and piled them on top of the pea and placed another twenty featherbeds on top of the mattresses.

KAY NIELSEN

A windswept princess seeks shelter in the castle and is welcomed by the king, who has the foresight to bring an umbrella when he lets in this “real” princess.

EDMUND DULAC

The canopy, the posters of the bed, the mattresses and featherbeds, and the massive timbers of the ceiling contain the tiny figure of the princess, who appears uncomfortable, despite the small mountain of cushioning protecting her from the pea. The many layers beneath the princess provide the artist with an opportunity to create several tiers of decorative touches.

KAY NIELSEN

The princess kneels atop the many mattresses in a room governed by extraordinary symmetry. The single light in the chandelier, the mirror over one chair, and the design on the bedstead, along with the princess herself, disrupt the symmetries.

The princess was going to sleep on them that night.

In the morning, everyone asked the princess how she had slept.

“Oh, just dreadfully!” the princess said. “I barely closed my eyes all night long!5 Goodness knows what was in that bed! I was lying on something so hard that I’m just black and blue all over. It’s really dreadful!”

Then of course everyone knew that she really was a princess, because she had felt the pea6 right through the twenty mattresses and twenty featherbeds. No one but a real princess would have skin that tender.

And so the prince took her as his wife, because now he knew that he had a true princess. And the pea was sent to the Royal Museum, where it is still on display,7 unless someone has stolen it.

Now you can see, that was a real story!8

W. HEATH ROBINSON

“I have scarcely closed my eyes the whole night through” reads the caption for this image of a distraught princess.

1. The Princess and the Pea. The literal translation of the title is “the princess on the pea,” emphasizing the test embedded in the story. I have kept the conventional English title, despite the fact that some translators insist that there is a critical difference in the formulation “on the pea.”

2. And he traveled all over the world in search of one. The prince leaves home to search the world for a wife, but his quest will prove to be in vain, for what he seeks, he will find at his doorstep. Unlike his mother, he has no accurate test for measuring authenticity and simply relies on his feeling that something is “not right.”

3. One evening a terrible storm broke out. As in “The Little Mermaid,” a storm signals a life-threatening situation, but it typically produces the opportunity for a romantic alliance. Lightning and thunder, once again, produce the chiaroscuro effects that repeatedly flash through Andersen’s fairy tales.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The old king goes to the door, candle in hand and massive keys at his side, to let in the princess.

4. It was a princess, and she was waiting outdoors. Like the French Donkeyskin and Cinderella, this princess conceals her nobility until it is put to a test. Rather than matching a foot to a shoe or a finger to a ring, she must reveal her sensitivity to a hidden object. Note that she appears out of nowhere and seems to be more of an orphan than a young woman of royal parentage.

5. “I barely closed my eyes all night long!” In a speech full of double entendres, the princess declares herself to have passed the test of authentic sensitivity but also creates the opportunity for risqué humor in retellings for adults.

6. she had felt the pea. Folklorists have noted that the pathological sensitivity, or “marvelous sensitiveness,” found in Andersen’s story is not common in fairy tales, but they have identified a few examples of it in fairy tales from some cultures. An Indian tale recounts the restlessness of a prince who thinks that he has slept on a wooden beam although nothing more than a hair is found in his bed. An Italian folktale called “The Most Sensitive Woman” describes how a prince’s quest for a marriage partner ends when he encounters a woman whose foot is bandaged after the petal of a jasmine blossom falls on her toe.

The Grimms had included “The Princess on the Pea” in one edition of their Children’s Stories and Household Tales, but they removed the tale once they realized that it belonged to a Danish literary tradition. Knowing that the Brothers Grimm were aware of his work, Andersen decided to pay them a surprise visit when he was in Berlin during the summer of 1844. It is not difficult to imagine his deep mortification when Jacob, the only one of the two brothers at home, was mystified by the presence of the Danish caller and declared that he had no idea who he was. A few weeks later, Jacob apologized in person to Andersen (he had read some of the tales in the interim and reported, “Now I know who you are”). The brothers remained on good terms with Andersen, and their Danish admirer spent time with them during the Christmas holidays in 1845.

Negative responses to the princess are based on what one critic calls “the cultural association between women’s physical sensitivity and emotional sensitivity, specifically, the link between a woman reporting her physical experience of touch and negative images of women who are hypersensitive to physical conditions, who complain about trivialities, and who demand special treatment” (Esrock, 25). The princess’s sensitivity is therefore often recalled by readers as a signal of bad manners rather than of her noble birth.

The feminist writer and essayist Vivian Gornick has read the princess’s sensitivity as a form of dissatisfaction that will define her life in negative terms: “She’s not after the prince, she’s after the pea. That moment when she feels the pea beneath the twenty mattresses, that is her moment of definition. It is the very meaning of her journey, why she has traveled so far, what she has come to declare: the dissatisfaction that will keep her life at bay.” For Gornick, the princess falls into “a petulance that mimick[s] the act of thinking. . . . Soon enough, through the painful logic of inborn grievance, the irritation becomes a wound, an infliction: a devotion and a destiny” (Gornick, 156–57).

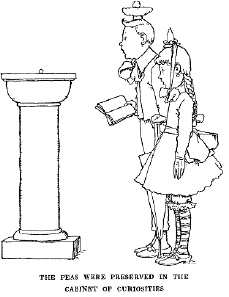

W. HEATH ROBINSON

A boy, book in hand, and a girl gaze with reverence and astonishment at the pea on the pedestal in the cabinet of curiosities.

The folklorist Christine Kawan has documented the existence of stories about boys who are subjected to a so-called bed test. These “pea seekers” or “bean kings” discover a pea or bean that appears to be an object of value. They journey to a castle, are given a bed of straw, and, after spending the night tossing and turning for fear of losing the pea or bean, are assumed to be of aristocratic lineage (they are unaccustomed to sleeping on straw) and are married to the princess (Kawan, 102).

7. the pea was sent to the Royal Museum, where it is still on display. For Andersen, the material objects of everyday life—needles, pincushions, and whistles—are endowed with special whimsical human qualities. Here, the pea is never endowed with human feelings, but it becomes an iconic object, signaling the princess’s special sensitivity, presumably not only to a pea under the mattress but also, in an optimistic interpretive move, to the wishes of her human subjects. Once placed in the Royal Museum, the pea becomes an objet d’art, a cult object endowed with an aesthetic and material value that creates the risk of theft.

8. that was a real story! The last line, in declaring the story to be “real,” suggests a parallel between the princess and the narrative about her. And yet, for the narrative, there is no “pea,” no object that will test for its authenticity. It is the narrator who vouches for the “real,” proclaiming the aristocratic lineage of his tale.