Nattergalen

“The Nightingale” reveals Andersen’s deep commitment to natural beauty over the artful and artificial. In choosing the fairy tale as his medium, Andersen hoped to align himself with the spontaneity of simple, “natural” forms and to empower his art with the same capacity as the nightingale’s song to create beauty, to provide pleasure, and to animate and transform.

Poets and singers are frequently referred to as “nightingales,” and Andersen’s contemporary, the singer Jenny Lind (whose repertoire included folk songs) was famously referred to as the “Swedish nightingale.” “Her voice stays with me, forever, in my story ‘The Nightingale,’ ” Andersen wrote in his travel diaries (Little, 215). Andersen’s friends dubbed him the “nightingale from Fyn”—a man whose literary song had earned him adulation and fame—and Andersen referred to himself as a “male Jenny Lind.” In The Fairy Tale of My Life, he hailed her vocal powers: “Her lovely youthful voice penetrated all hearts! Here truth and nature prevailed; everything assumed significance and clarity” (208). In a memoir published by Charlotte Bournonville, daughter of the famous ballet master who counted himself among Andersen’s friends, the following story (which Andersen may well have heard) is recounted:

One of my father’s dearest friends, a very musical young man, was seriously ill, and his sadness at not being able to hear Jenny Lind sing did quite a lot to make his condition even worse. When Jenny learned that news, she cried: “Dear Mr. Bournonville, allow me to sing for this man who is so ill!” Perhaps it was a dangerous experiment to expose a person who was mortally ill to such an emotional experience, but it worked. After he heard the beautiful singing . . . he was on the road to recovery.

The modesty, generosity, and passion of true art produced by those devoted to their craft contrasts sharply with the empty pleasure of an art as it is practiced by mechanical creatures, who can engage in little else but vacuous mimicry.

Igor Stravinsky’s opera The Nightingale, based on Andersen’s story, premiered in Paris in 1914. Several years later, Stravinsky composed a symphonic poem, “Song of the Nightingale,” for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The ballet was first performed in 1920, with sets by Henri Matisse and choreography by Léonide Massine.

Jerry Pinkey’s account of his decision to illustrate Andersen’s “Nightingale” reveals how new images for old stories can have designs on the reader. For him, the girl in the kitchen, who is attuned to nature, becomes as important as the nightingale in restoring the Emperor’s health:

The remarkable story of “The Nightingale” has always intrigued me, and in the creation of this adaptation, the plain little bird with a magnificent voice and a big heart became a symbol of the healing power of nature. The little kitchen girl, who knows where the nightingale lives, became a symbol of hope for the downtrodden. And the king, who cares for his people but is out of touch with them, learns what it means to feel vulnerable through his own illness. In the end the king’s recovery is made possible by two of his most humble subjects, the little kitchen girl, and the nightingale.

Kara Dalkey’s novel The Nightingale (1991) situates the events in Japan and transforms the nightingale into a young woman who plays the flute.

In China, as you may know, the Emperor is Chinese,2 and everyone there is also Chinese. This story took place many years ago, but that’s exactly why you should listen to it, before it’s forgotten.3

The Emperor’s palace was the most magnificent in the world. It was made entirely of fine porcelain, so costly and delicate that you had to be careful when you touched it. In the garden you could find the most wondrous flowers. The most splendid among the flowers were trimmed with little silver bells that jingled, and you couldn’t walk by without noticing them. Yes, everything was arranged quite artfully in the Emperor’s garden,4 which stretched so far back that even the gardener could not say where it ended. If you kept on walking, you reached the loveliest forest with tall trees and deep lakes. The forest stretched all the way out to the deep, blue sea. Tall ships sailed right under the branches of the trees. In those branches lived a nightingale whose song was so enchanting that even a poor fisherman, who had many chores before him, would pause when taking his nets in at night to listen. “My God! That’s really beautiful,” he would say. But then he would return to his chores and forget all about the bird’s song. The next evening, when the fisherman was back at work, the bird would start singing again, and he would say the same thing:5 “My God! That’s really beautiful.”

EDMUND DULAC

The fisherman pauses to listen to the nightingale hidden behind the branches of the tree. Marked by poverty, he experiences a moment of sublime respite from his labors.

Travelers came from all over the world to visit the Emperor’s city and to admire his palace and gardens. If they happened to hear the nightingale singing, they would all agree: “That’s just the best of all.”

When the travelers returned home, they would describe what they had seen, and learned men wrote many books about the city, the palace, and the garden. They never forgot the nightingale—in fact they praised the bird above all other things. Those who could write poetry composed the loveliest poems about the nightingale6 that lived in the forest by the deep sea.

The books themselves traveled around the world, and some of them found their way to the Emperor of China. One day, he was sitting on his golden throne, reading one book after another, nodding his head in delight over the splendid descriptions of his city, palace, and garden. “The nightingale is the best of all!” the books declared.

“What on earth!” the Emperor exclaimed. “A nightingale! I don’t know a thing about it! Is it possible that a bird like that exists in my empire, let alone in my own garden?7 And to think that I had to read about it in a book.”

The Emperor summoned the Chamberlain, who was so refined that when anyone of a lower rank had the audacity to address him or to ask a question, his only reply was “Puh!”8 which really means nothing at all.

“Apparently there is a truly extraordinary bird around here called a nightingale,” said the Emperor. “They say it’s better than anything else in all my domains. Why hasn’t anyone said a word to me about it?”

“I’ve never heard anyone say a word about it,” the Chamberlain said. “And no one has ever presented the bird at the imperial court.”

“I want it to appear here tonight to sing for me,” the Emperor said. “The rest of the world knows more about what’s in my kingdom than I do!”

“I’ve never heard anyone say a word about it,” the Chamberlain said again. “But I shall look for it, and I will find it.”

But where could the nightingale be? The Chamberlain sped up and down the stairs, through rooms and corridors, but nobody he met had ever heard of the nightingale. And so the Chamberlain raced back to the Emperor and told him that the bird must have been in a fable invented by those who write books. “Your Imperial Majesty should not believe what people write today. It’s all made up and about what can be called black magic.”

“But the book I was reading was sent to me by the mighty Emperor of Japan,” the Emperor said. “So it really must be true. I am determined to hear this nightingale. It must be here by this evening. I’ve granted it my high imperial favor. If it doesn’t show up by then, I’ll have every courtier punched in the stomach right after supper.”9

“Tsing-pe!”10 the Chamberlain shouted, and once again he sped up and down the stairs, through all the rooms and corridors. And half the court ran along with him, for no one wanted to be punched in the stomach. Everyone was asking questions about the mysterious nightingale, which was so famous all over the world but unknown at home.

They finally found a poor little girl in the kitchen,11 who said: “Good Lord! The nightingale? Of course I know all about it. Yes, indeed, it can really sing! Every evening they let me take home a few scraps from the table to my poor, sick mother. She lives down by the sea. When I start back, I am so tired that I have to stop to rest in the woods. That’s when I hear the nightingale sing. It brings tears to my eyes. It’s just as if my mother were giving me a kiss.”

“Little kitchen maid,” the Chamberlain said. “I’ll arrange a lifetime post for you in the kitchen and give you permission to watch the Emperor dine if you can take us to the nightingale. It is supposed to give a command performance at court tonight.”

KAY NIELSEN

The nightingale is little more than a speck in the landscape, but the kitchen maid, in a setting of rare beauty, listens to his song enthralled. She is able to renew her journey after the restorative song.

And so they all set off for the forest, to the place where the nightingale was said to sing. Half of the court followed. On the way into the forest a cow began mooing.

“Aha!” said the royal squires. “That must be it. What remarkable power for such a tiny creature. We’re sure that we’ve heard that song once before.”

“No, those are cows lowing,” the little kitchen girl said. “We still have a long way to go.”

Then the frogs began croaking in the marshes.

“How lovely!” the imperial Chinese chaplain declared. “It sounds just like little church bells.”

“No, those are just frogs,” said the little kitchen maid. “But I have a feeling we will hear the nightingale soon.

Then the nightingale began to sing.

“There it is,” said the little kitchen maid. “Just listen. And now you can see it!” And she pointed to a little gray bird perched on a branch.

“Can it be?” exclaimed the Chamberlain. “That’s not at all how I imagined the bird to be. How plain it looks!12 It must have lost all its color from seeing all the distinguished persons gathered around.”

“Little nightingale,” the kitchen maid called out in a loud voice. “Our gracious Emperor so wants you to sing for him.” “With the greatest pleasure,” the nightingale replied, and it sang to everyone’s delight.

“It sounds just like crystal bells,” the Lord Chamberlain said. “And just look at the bird’s little throat—you can tell it’s singing with all its might. It’s astonishing that we have never heard it before. It will be a great success at court.” “Shall I sing again for the Emperor?”13 the nightingale asked, for it believed that the Emperor was present.

“My splendid little nightingale,” the Lord Chamberlain said. “I have the great honor of inviting you to court this evening, and there you will enchant his Imperial Grace with your charming voice.”

“My song sounds best outdoors,” the nightingale replied, but it was glad to return with them when it learned of the Emperor’s wishes.

The palace had been cleaned and polished with great care. The walls and floors, made of porcelain, were gleaming from the light of thousands of golden lamps. The loveliest flowers, trimmed with little bells, had been placed in the corridors. The commotion from all the comings and goings made the bells start ringing, and you could scarcely hear yourself think.

In the middle of the great hall in which the Emperor was seated, a golden perch had been set up, and it was for the nightingale. The entire court had assembled there. The little kitchen maid had been given permission to stand behind the door, for she now held the title of Real Kitchen Maid. People were dressed in their finery, and, when the Emperor graciously nodded, everyone fixed their eyes on the little gray bird.

The nightingale’s voice was so lovely that tears began to fill the Emperor’s eyes and roll down his cheeks. The bird sang even more beautifully, and the music went straight to his heart. The Emperor was so delighted that he ordered his own golden slipper to be hung around the nightingale’s neck.14 But the nightingale graciously declined it and declared that it had received reward enough.

“I have seen tears in the eyes of the Emperor,” it said. “For me that is the greatest treasure. The tears of an Emperor have a wondrous power. God knows that I have received my reward.” And it sang once again with a sweet, sublime voice.

“We’ve never seen such lovable flirtatiousness,” the ladies all declared. And they put water in their mouths so they would twitter whenever they talked. They were hoping that they too could be nightingales. Even the footmen and chambermaids declared that they were satisfied, which is saying a lot, for they are the hardest to please. Yes, indeed, the nightingale was a complete success!

EDMUND DULAC

The chamberlain is appalled to discover that the nightingale is so plain and gray. Illuminated by the lamp, the nightingale is that brilliant, rare object that lights up the world with its beautiful song.

The nightingale was supposed to stay at the palace and have its own cage, as well as the freedom to go on outings twice a day, and once at nighttime. Twelve servants stood in attendance, each one holding tight to a silk ribbon attached to the bird’s leg. There was no pleasure at all in outings like that.

The whole town was talking about the remarkable bird. If two people happened to meet, the first just said “Night!” and the other would respond with “Gale!” and then they would both just sigh, with no need for words. What’s more, eleven grocers named their children “Nightingale,” although not a single one of them was able to carry a tune.

One day a big package arrived for the Emperor. The word “Nightingale” had been written on it.

“It must be a new book about our famous bird,” the Emperor said. But it was not a book. Inside the box was a work of art, a mechanical nightingale15 that was supposed to look just like the real one except that it was covered with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires.16 When it was wound up, the mechanical bird sang one of the melodies of the real bird, all the while beating time with its gleaming tail of gold and silver. Around its neck hung a little ribbon, and on it were the words: “The Emperor of Japan’s nightingale is a paltry thing compared with the one owned by the Emperor of China.”

“Isn’t it lovely!” they all said, and the person who had delivered the contraption was immediately given the title Supreme Imperial Nightingale Transporter.

“Let’s have them sing together. What a duet that will be!” And so the two birds sang a duet, but it didn’t work, because the real nightingale had her own style, while the mechanical bird ran on cylinders. “You can’t blame it for that,” the Music Master said. “It keeps perfect time, entirely in line with my theories.” And so the mechanical bird sang on its own. It pleased them all just as much as the real bird, and on top of that it was far prettier to look at, for it sparkled just the way that bracelets and brooches do.

The mechanical bird sang the same tune thirty-three times without tiring out. Everyone would have been happy to hear it again, but the Emperor thought that the real nightingale should also take a turn. But where had it gone? No one had noticed that it had flown out the window, back to the green forests.

“Well, what kind of behavior is that?” the Emperor exclaimed. And the courtiers all sneered at the nightingale, declaring it to be a most ungrateful creature. “Fortunately, the best bird of all is still with us,” they said. And the mechanical bird started singing the same tune, now for the thirty-fourth time. But no one knew it by heart yet, because it was a terribly difficult piece. The Imperial Music Master lavished great praise on the mechanical bird. Yes, he assured them, this contraption was far better than any real nightingale, not only because of how it looked on the outside with its many beautiful diamonds but also because of its inner qualities.

“Ladies and gentlemen—and above all Your Imperial Majesty: You never know what will happen when it comes to a real nightingale. But with a mechanical bird everything is completely under control. It will sound a certain way, and no other way. You can explain it; you can open it up and take it apart;17 you can see how the mechanical wheels operate, how they whirl around, and how one interlocks with the other.”

“My sentiments precisely,” they all said. And the Music Master was given permission to put the bird on display for all to see on the following Sunday. They too should hear it sing, the Emperor declared. And hear it they did, with so much pleasure that it was as if they had all become tipsy from drinking tea, in the Chinese fashion. Everyone said “Oh!” and held up a finger—the one you lick the pot with—and then nodded. But the poor fisherman, the one who had heard the real nightingale sing, said: “That sounds nice enough, and it’s very close to the real thing. Something’s missing, but I’m not sure what it is.”

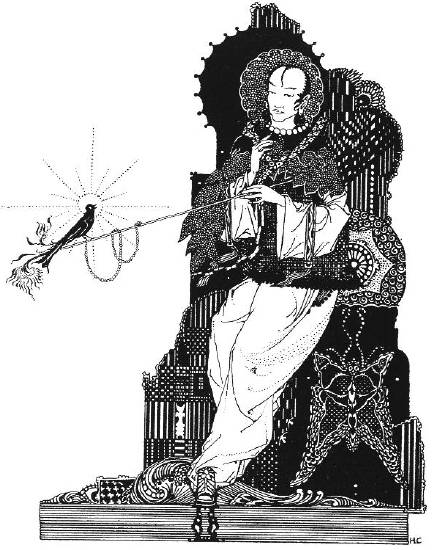

HARRY CLARKE

Few illustrators choose to depict the artificial bird, but here it sings for the Emperor, who clearly values opulence and luxury.

The real nightingale was banished from the realm.

The mechanical bird took up its place on a silk cushion near the Emperor’s bed. It was surrounded by the many gifts people had given it—gold and precious stones. It had also risen in office to become Supreme Imperial Nightstand Singer. In rank it was number one to the left, for the Emperor believed the left side of the body was nobler. After all, that’s where the heart is, even the Emperor’s.

The Music Master wrote twenty-five volumes about the mechanical bird18—books so learned, long-winded, and full of obscure Chinese words that everyone claimed to have read them and understood them, because otherwise people would have said they were stupid and they would have been punched in the stomach.

A year went by in this way, and the Emperor, his court, and all the people in China knew every little twitter of the mechanical bird’s song by heart, and that was exactly why they liked it so much more than anything else. They could sing its song on their own, and they did. Boys and girls in the streets sang: “Zi-zi-zi! Click, click, click,”19 and the Emperor sang along with them. Oh, yes, it was that lovely!

But one evening, when the mechanical bird was singing with all its might and the Emperor was lying in bed listening, something inside the bird went “boing!” Something else burst and went “whirr!” Gears began spinning wildly, and then the music stopped.

The Emperor jumped right out of bed and sent for the royal physician. But what could he do? They summoned a watchmaker,20 who deliberated and investigated, then finally patched up the bird after a fashion. The watchmaker warned that the bird had to be kept from overdoing things, for the cogs inside it were badly worn and, if they were replaced, the music would not sound right. That was really dreadful! No one dared to let the bird sing more than once a year, and even that was almost too much. But before long the Music Master gave a little speech full of big words and claimed that the bird was just as good as new. And so it was just as good as new.

Five years went by, and the entire country was in deep mourning, for everyone was really fond of their ruler, and he was ill—so ill that he would probably not survive. A new Emperor had already been chosen. People were standing outside in the streets, waiting to ask the Chamberlain how the Emperor was faring.

“Puh!” he said and shook his head.

The Emperor was lying in a huge, magnificent bed, and he looked cold and pale. All the courtiers were sure that he was already gone, and they were hurrying to get out of the palace to pay homage to the new Emperor. The footmen darted around, spreading the news, and the chambermaids were holding a big party and drinking coffee. Mats had been put down in all the rooms and passageways to muffle the sound of footsteps, and that’s why it was so quiet, ever so quiet. But the Emperor was not yet dead. He lay stiff and pale in his magnificent bed with its long velvet curtains and heavy golden tassels. High above him was an open window, and the moon was shining in through it on the Emperor and his mechanical bird.

The poor Emperor could barely breathe. He felt as if something was sitting on his chest.21 When he opened his eyes, he realized that it was Death, and he was wearing the Emperor’s crown on his head, holding the Emperor’s golden sword in one hand, and carrying the Emperor’s splendid banner in the other. Eerie-looking faces peered out between the folds of the great velvet curtains. Some looked perfectly dreadful, others were gentle and sweet. They were the Emperor’s deeds, good and bad, and they had come back to haunt him now that Death was seated on his heart.

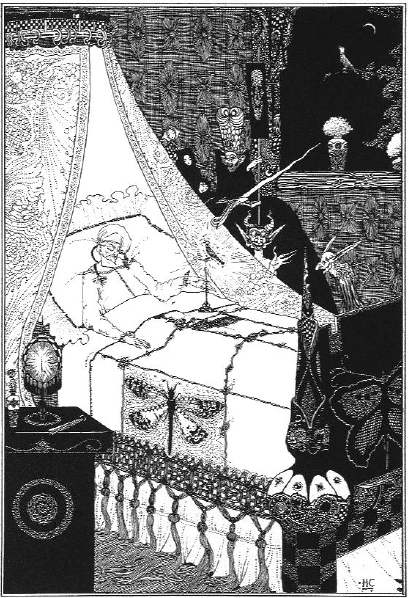

EDMUND DULAC

A depleted Emperor lies in bed, near death. The figure of Death is marked by emaciated boniness, but also by touches of beauty that include a helmet of gold, earrings, and peacock feathers.

“Do you remember this?” they whispered one after the other. “Do you remember that?” And they told him so many things that he began to break out into a cold sweat.

“I never knew that!” the Emperor exclaimed. “Music, music! Sound the great drum of China,” he cried, “so that I won’t have to listen to everything they are saying.”

But they would not stop, and Death nodded, like a Chinaman,22 at every word that was uttered.

“Music, music!” the Emperor shouted. “My blessed little golden bird! Sing for me, sing! I’ve given you gold and precious jewels. I’ve even put my golden slipper around your neck. Sing for me, please sing!”

But the bird remained silent. No one was there to wind it up, and without help, it couldn’t sing. Death kept on looking at the Emperor with his great hollow sockets, and everything was quiet—so dreadfully quiet.

Suddenly the loveliest song could be heard from just outside the window. It was the little nightingale—the living one—perched on a branch outdoors. It had learned of the Emperor’s distress and had come from afar to sing and offer comfort and hope. While it was singing, the phantoms all around began to grow more and more pale, and the blood in the Emperor’s enfeebled body began to flow more and more quickly. Death itself was listening,23 and said, “Keep singing, little nightingale! Keep singing!”

“Yes, I will, if you give me the imperial golden sword! And if you give me the splendid banner! And if you give me the Emperor’s crown!”

Death returned each of the treasures in exchange for a song. The nightingale kept on singing. It sang about silent churchyards where white roses grow, where elder trees make the air sweet, and where the grass is always green, watered by the tears of those left behind. Death began to long for his own garden and drifted out the window in a cold, gray mist.

“Thank you, thank you, you divine little bird!” the Emperor exclaimed. “Now I recognize you. I banished you once from my realm. And even then you sang until all those evil faces disappeared from around my bedside. You drove Death from my heart. How can I ever repay you?”

“You have already given me my reward,” the nightingale said. “I brought tears to your eyes when I first sang for you, and I will never forget that about you. Those are the jewels that warm the hearts of singers. But go to sleep now and grow hale and hearty while I sing to you.” The bird continued singing until the Emperor fell into a sweet slumber—a gentle and refreshing sleep.

The sun was shining through the windows when the Emperor awoke, restored and healthy. Not one of his servants had yet returned, for they all believed that he was dead. The nightingale was still there, singing.

“You must stay with me forever,” the Emperor said. “You only have to sing when you wish, and, as for that mechanical bird, I’ll smash it into a thousand pieces.”

“Don’t do that,” the nightingale said. “It has done the very best it could—and you really should keep it. I can’t live inside the palace, but let me come for a visit whenever I wish. In the evening, I’ll alight on the branch by your window and bring you pleasure and wisdom with my song. I will sing about those who are happy and those who suffer. I’ll sing about the good and evil that remains hidden from you. A little songbird gets around—to the poor fishermen, to the rooftops of farmers, to everyone who is far away from you and your court. I love your heart more than I love your crown, but there is something sacred about your crown.24 I’ll come to sing for you, but you must promise me one thing.”

“Anything!” the Emperor replied, standing there in the imperial robes that he himself had donned and holding his heavy golden sword against his heart.

“Just one thing,” the nightingale asked. “You must not let anyone know that you have a little bird that tells you everything,25 for things will go better that way.”

Then the nightingale flew away.

The servants came in to attend their dead Emperor. Yes—there they stood. And the Emperor said to them, “Good morning!”26

KAY NIELSEN

The nightingale sings triumphantly, perched on Death’s scythe, which seems to be racing away from the Emperor’s bed.

1. The Nightingale. The nightingale (“singer of the night”) is a songbird of reddish-brown plumage found in Great Britain, Asia, Africa, and on the Continent. Its celebrated song refers to the male’s breeding-season calls, which are endowed with an impressive range of whistles, gurgles, and trills. Although the nightingale sings both day and night, the nocturnal refrain is considered unusual, since few other birds sing at night—hence the word “night” in its name in English and in other languages. The nightingale has enjoyed a robust literary life. It appears in Ovid’s story of Procne, Philomela, and Tereus, which ends with the transformation of Philomela into a nightingale. The thirteenth-century Middle English poem “The Owl and the Nightingale” sets down a debate between a sober owl with ascetic and unworldly views and a cheerful nightingale, who is an exponent of pleasure and beauty.

John Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” (1819) apostrophizes the expressive power and transcendent beauty in the bird’s melody. Keats’s close companion, Charles Brown, describes the origins of the poem: “In the spring of 1819 a nightingale had built her nest near my house. Keats felt a tranquil and continual joy in her song; and one morning he took his chair from the breakfast table to the grass-plot under a plum-tree, where he sat for two or three hours. When he came into the house, I perceived he had some scraps of paper in his hand, and these he was quietly thrusting behind the books” (Rollins, The Keats Circle, II, 65). For Keats, the nightingale is a model of creative artistry, singing with a “full-throated ease” so soulful and expressive that it inspires in the poet a sense of morbid self-abandonment (“Now more than ever seems it rich to die”).

In Oscar Wilde’s “The Nightingale and the Rose,” the bird impales itself on a thorn in order to transform a white rose into a red one. She (Wilde’s nightingale is designated as female) sings of the “birth of passion” and celebrates “the Love that is perfected by Death, of the Love that dies not in the tomb.” In contrast with the callous student in the tale, who dismisses love as inferior to logic and returns to the study of metaphysics, the nightingale dies with a thorn in its breast, a martyr to love and passion. Wilde’s tale might have been inspired by Andersen’s story, in which the nightingale is not allied with death but sings in a fashion that challenges and defies the power of death.

The Danish term nattergal (nightingale) contains within it the term gal (madman).

2. the Emperor is Chinese. Andersen establishes a “once upon a time” feeling by setting the tale in a distant, exotic land and in the remote past. That the Emperor of China is also a “Chinaman” (as some translations of the story have it) may not be as obvious as first appears, given the number of foreign lands controlled by colonial powers during the nineteenth century. In his almanac entry for October 11, 1843, Andersen declared that the tale, which was written in a single day, “began in Tivoli,” Copenhagen’s new amusement park, which featured pagodas, Chinese lanterns, and peacocks. The apparent tautology has a humorous and charming ring to it, suggesting a certain childlike levity. Andersen’s travels never took him beyond Istanbul and Athens, and his contact with China was limited to European Chinoiserie, an artistic style that developed in the seventeenth century and continued to be popular through the nineteenth century.

3. that’s exactly why you should listen to it, before it’s forgotten. Andersen lived in an era when old wives’ tales were in retreat. And, like the Grimms who preceded him, he felt some anxiety about oral story-telling traditions, which were rapidly vanishing with the migration of certain forms of labor from the domestic to the industrial sphere. Note that Andersen connects himself to those traditions as a teller of tales (“you should listen”) rather than to the writing practices in which he is actually engaged.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The nightingale, framed by trees, leaves, and acorns, sings with full-throated pleasure.

4. Yes, everything was arranged quite artfully in the Emperor’s garden. Fragility, delicacy, and beauty: these are, as always, the characteristics of the gardens in Andersen’s tales, the sites where nature meets culture. Like the undersea world in “The Little Mermaid,” the Emperor’s castle and gardens are places of exquisite beauty, where nature has been improved by those with refined aesthetic sensibilities.

5. he would say the same thing. Does beauty have a lasting effect? The fisherman’s response to the nightingale’s song suggests that those who habitually dwell in the vicinity of beauty remain unaffected by its transformative power and merely carry on with their daily chores. By contrast, the nightingale is a rare sight for visitors to the city, and its melody haunts them.

6. composed the loveliest poems about the nightingale. Here, the rich literary tradition that enshrines the nightingale as the bird of love, passion, tragedy, and beauty is invoked. The refrain of the bird inspires the song of poets—and also the work of storytellers.

7. “Is it possible that a bird like that exists in my empire, let alone in my own garden?” Andersen would surely have identified with a bird of song that is so famous abroad but unknown at home. He complained endlessly about how badly the Danes treated him and believed that his work was appreciated abroad far more than at home. And indeed, the critical reception of his work was far more positive in foreign lands than it was in Denmark. In Munich, Andersen mused about how he longed to return to Copenhagen, although he was discouraged by news about contemptuous reviews of his work: “Letters from Denmark told how my work was discarded, destroyed, how I was still the weed in the otherwise healthy garden of young Danish poets. I felt nervous about coming under attack again, being caught in the suffocating seas of criticism” (Travels, 72–73).

8. his only reply was “Puh!” In the Danish original, the reply is “P,” a sound with no more significance than its English equivalent. Perhaps all that Andersen reached for here was a consonant with a brusque, dismissive sound.

9. “I’ll have every courtier punched in the stomach right after supper.” One Andersen scholar points out that “The Nightingale” presents a China “composed of all the West’s shallow misconceptions of the Celestial Empire: a sort of marionettetheater China where everything is of porcelain, gold, or silk, with people nodding their heads like dolls; where conventions are so ingeniously devised as to seem actually Chinese; where the emperor can have his courtiers punched in the stomach after supper when they have displeased him; where those in authority are ridiculously impressed with their own dignity and the common people foolishly ape their masters” (Grønbech, 103). In this ritualized culture, where arrogance, sophistry, and rigid hierarchies rule supreme with brutal results, the nightingale represents a unique instance of spontaneity and pleasure. The bird’s soulfulness and generosity contrast sharply with the courtiers’ selfserving callousness.

10. “Tsing-pe!” Most likely a variation of the Chinese “ch’in p’ei,” or “as you please,” but the phrase could also be nonsense. Andersen’s playful use of gibberish anticipates Lewis Carroll’s insights into the appeal of nonsense words for children. Both authors had a clear sense of how to use words to create wonders.

11. They finally found a poor little girl in the kitchen. The kitchen maid is a Cinderella figure who would seem the least likely person to locate the nightingale. Unlike the courtiers and imperial rulers in the tale, she is a person of humble origins who remains unimpressed by the royal entourage. But she is quite happy to accept a promotion to “Real Kitchen Maid,” a title that spoofs the 1717 Danish law that raised a person’s rank with the addition of the term “real.”

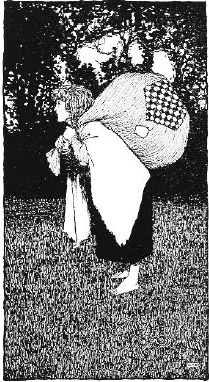

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The kitchen maid has a heavy load to carry as she makes her way to her mother’s home. On her way, she is stopped in her tracks by the arresting sound of the nightingale’s song.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The kitchen maid has put down her bundle, and the courtly delegation stands in awe of a nightingale that combines a modest appearance with an enchanting song. Robinson’s humans have a real decorative solidity that contrasts powerfully with the airy lightness of the delicate objects in the sparse landscape.

12. “How plain it looks!” Nicolai Bøgh kept a diary during a journey taken with Andersen in 1873. He reported Andersen’s views on Jenny Lind: “They say Jenny Lind was hideous to look at, and maybe she was. The first time she walked on stage, I said the same: ‘She’s hideous’ . . . but then she sang and became divinely beautiful. She was like an unlit lamp when she came in, and then, when you lit the lamp and she began to speak, it was as if her spirit cast a divine radiance on the stage and every seat in the theater. You weren’t in the theater, you were in church” (Frank and Frank, 151).

Likewise, the nightingale itself is an unprepossessing bird, slightly larger than a robin, brown, with a broad tail and a plain appearance. Many illustrators emphasize the bird’s drabness and diminutiveness, which contrast with the lavish trappings of the court.

HARRY CLARKE

An intrigued emperor listens to the vibrant sounds of the nightingale.

13. “Shall I sing again for the Emperor?” The nightingale is not only gifted and modest but also completely obliging, willing to sing on command and to leave its home in the woods to sing at court. Moreover, unlike its mechanical counterpart, the nightingale is able to vary and improvise.

14. he ordered his own golden slipper to be hung around the nightingale’s neck. The European folktale “The Juniper Tree” features a bird that sings as melodiously as the nightingale of Andersen’s tale. In the Grimms’ recording of the tale, the bird asks for rewards while repeating its song. In one instance, it receives red slippers and picks them up with one claw, while holding a gold chain with the other.

15. Inside the box was a work of art, a mechanical nightingale. Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium” contains an echo of Andersen’s “Nightingale.”

16. it was covered with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. The nightingale is covered with precious stones in the classic fairytale color combination of white, red, and blue. Fairy tales, as Max Lüthi has emphasized, are concerned with surface beauty: everything that glitters, sparkles, and glows. The mechanical nightingale represents the pinnacle of artifice and human invention, and it stands in stark contrast to the “plain” nightingale, who lives in the woods and sings of nature’s beauty and poetry. Artifice is set against art in the rivalry between the mechanical nightingale and the undomesticated avian creature that lives in natural surroundings. Similar themes come up in Andersen’s tale “The Swineherd.”

17. “You can explain it; you can open it up and take it apart.” The superiority of the mechanical bird is based on the principle that the familiar, rational, and logical are more comforting and reassuring than the mysterious, irrational, and magical. The music master represents Enlightenment views that elevate reason over emotion and celebrate the human capacity to demystify the world.

18. twenty-five volumes about the mechanical bird. Once again the written word is invoked as the source of pedantic and arcane efforts to explain the obvious. Just as nature is set in opposition to artifice, so too the melodious song of the nightingale is set against the desiccated written word. Writing fails to enrich or augment, and contributes nothing to the beauty created by the nightingale, even in its mechanical form. The figure of the music master mocks the pedantry of the renowned Danish writer and critic Johan Ludvig Heiberg.

19. “Zi-zi-zi! Click, click, click.” That the story is designed to be read out loud (and Andersen famously loved to read his fairy tales to captive audiences) becomes evident from the various amusing sounds in the text—ranging from the Chamberlain’s “Puh” to noises made by the mechanical nightingale. Andersen’s use of onomatopoeia becomes more pronounced over time. Beginning with the sound of the matches in “The Little Match Girl” through the chants of the robber girl in “The Snow Queen” to the sound of the fire drum in “The Golden Treasure,” Andersen used language expressively and in ways that suggest how attuned he was to acoustical effects. As Jens Andersen points out, he also created the “most splendid military title in all of world literature: ‘Billygoat-Leg-Field-Marshal-Brigadier-General-Commander-Sargeant’” (Andersen, 239) in “The Shepherdess and the Chimneysweep.” Onomatopoetic effects and playful names and titles, as we know from the works of writers like Lewis Carroll and Roald Dahl, work magic in getting the attention of children.

20. They summoned a watchmaker. Deism, a system of thought prominent during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, sometimes portrayed God as an indifferent watchmaker, who set up the universe and simply allowed it to run. Operating as precisely as the machines crafted by humans, the universe was seen to evolve in an orderly fashion.

21. He felt as if something was sitting on his chest. In describing the Emperor’s condition, Andersen is drawing on a medical condition known as “sleep paralysis,” in which an individual experiences hypnagogic hallucinations and partial muscle paralysis upon awakening. Sufferers report feeling an evil presence in the room, often in the form of a threatening incubus, hag, or monster. As in Henry Fuseli’s famous painting “The Nightmare,” there is the sensation that someone or something is sitting on the chest, causing suffocation. Episodes are often terminated through the perception of sounds emanating from the real world.

HARRY CLARKE

Both artificial bird and nightingale appear to be singing the Emperor back to life, as demons gather around his bedside. “Music! Music!” cried the Emperor. “You little precious golden bird, sing!” The illustrator does not seem concerned about fidelity to the text in this case. He also removes the oriental element from the story through the illustration.

22. Death nodded, like a Chinaman The reference to the habit of nodding among the Chinese may be linked with the porcelain mandarin figures imported from China in the nineteenth century. The figures had heads attached to the body by a spring and would nod when tapped, much like today’s bobbleheads. In Danish, a yes-man is often referred to as a mandarin. The porcelain mandarin figure can be linked with the mechanical nightingale and with the notion of the automatonlike behavior that characterizes the Emperor before his transformation. In “The Shepherdess and the Chimneysweep,” a porcelain mandarin figures prominently.

23. was listening. In ancient China, music was regarded as having transcendent power. In Andersen’s story, it even has the capacity to conquer death. For nineteenth-century philosophers and other contemporaries of Andersen, like Schopenhauer, music ranked highest in the hierarchy of the arts because it does not engage in any effort to imitate, copy, or duplicate. Instead music directly captures and expresses feelings such as misery, pain, sorrow, joy, or horror.

24. something sacred about your crown. All his life, Andersen harbored an ambivalent attitude toward monarchs and the nobility, combining contempt with reverence. However, some biographers, most notably Jack Zipes, see him as consistently “servile” and “opportunistic.” For Zipes, Andersen’s tales revealed a “false consciousness” and represented “literary exercises in the legitimation of a social order to which he subscribed” (Zipes 2005, 75). In “The Nightingale,” Andersen mirrors his own sycophantic relationship to the aristocracy when he restores “the relationship of servitude” between bird and emperor: “Feudalism has been replaced by a freemarket system; yet, the bird/artist is willing to serve loyally and keep the autocrat in power” (Zipes 2005, 67).

25. “You must not let anyone know that you have a little bird that tells you everything.” The bird takes on a supervisory role, monitoring and reporting on the behavior of the Emperor’s subjects. Note the emphasis on good deeds and bad deeds in the deathbed scene. The story ends on a moralizing note, suggesting that the nightingale does not just create beauty but also polices the ethical dimension of human actions. As in “The Little Mermaid,” the moral duties assumed by the main character seem like an afterthought, and it is odd to see the nightingale, who loves the solitude of the woods, suddenly take on a social function.

26. “Good morning!” The Emperor’s subjects are obviously receiving a shock, but the bright, sunny greeting comes as something of a surprise for the reader as well. The reversal in the Emperor’s health and fortune seems to usher in a new day marked by good cheer and enlightened rule. The Emperor will, presumably, no longer threaten his subjects with punches in the stomach.