Den Ville havfrue

With “The Little Mermaid,” Andersen believed that he had created one of his most moving fairy tales. “I suffer with my characters,” he told his friends again and again, and his readers too have endured the pain of his beautiful aquatic creature. P. L. Travers, author of the Mary Poppins books, found Hans Christian Andersen to be a master in the art of torture. “How much rather would I see wicked stepmothers boiled in oil . . .,” she declared, “than bear the protracted agony of the Little Mermaid or the girl who wore the Red Shoes.” In Andersen’s tales, suffering can become a badge of spiritual superiority, and his downtrodden protagonists often emerge triumphant after enduring seemingly endless humiliations.

The little mermaid has worldly ambitions that run in directions other than silent suffering. Drawn to the upper world, she is eager to sail the seas, climb mountains, and explore forbidden territory. Donning boy’s clothing, she goes horseback riding with the prince, crossing gender boundaries in unprecedented ways. For all her passion for adventure and life, she is, despite her pagan nature, a creature of compassion, unwilling to sacrifice the prince’s life for her own. The spirited curiosity that impels her to seek out the world of humans is also precisely what defeats her, leading to the condition of suffering that Travers found so troubling.

The animated Disney version of “The Little Mermaid” (1989) deviates sharply from the tale that inspired it. It may end happily with a marriage, but as Marina Warner points out, “The issue of female desire dominates the film, and may account for its tremendous popularity among little girls: the verb ‘want’ falls from the lips of Ariel, the Little Mermaid, more often than any other—until her tongue is cut out” (Warner, 403). Still, the Disney version has in many ways kept Andersen’s story alive, even if it has a heroine and an ending radically different from the story that inspired it.

Far out at sea,2 the water is as blue as the petals of the prettiest cornflowers and as clear as the purest glass. But it’s very deep out there, so deep that even the longest anchor line can’t touch bottom. You would have to pile up countless church steeples, one on top of the other, to get from the bottom of the sea all the way up to the surface. The sea people live down there.3

Now you mustn’t think for a moment4 that there is nothing but bare, white sand down there. Oh, no! The most wondrous trees and plants grow at the bottom of the sea, with stalks and leaves so supple that they stir with life at the slightest ripple in the water. The fish everywhere, large and small, dart between the branches, just the way birds fly through the trees up here. At the very deepest spot of all stands the castle of the Sea King.5 Its walls are coral, and the tall, arched windows are made of the clearest amber. The roof is formed of shells that open and close with the current. It’s a beautiful sight, for each shell has a dazzling pearl, any one of which would make a splendid jewel in a queen’s crown.

The Sea King had been a widower for many years, and his aged mother kept house for him. She was a wise lady, but also very proud of her noble birth. And that’s why she wore twelve oysters on her tail, while everyone else of high rank had to settle for six. In every other way she deserved great praise, for she was deeply devoted to her granddaughters, the little sea princesses. They were six beautiful children, but the youngest was the fairest of them all. Her skin was as clear and soft as a rose petal. Her eyes were as blue as the deepest sea. But like all the others, she had no feet,6 and her body ended in a fish tail.

All day long the sea princesses played in the great halls of the castle, where real flowers were growing right out of the walls. When the large amber windows were open, fish swam right in, just as swallows fly into our homes when we open the windows. The fish glided up to the princesses, ate out of their hands, and let themselves be caressed.

Outside the castle there was an enormous garden with trees that were deep blue and fiery red. Their fruit glittered like gold, and their blossoms looked like flames of fire, with leaves and stalks constantly aflutter. The soil itself was the finest sand, but blue like a sulphur flame. A wondrous blue glow permeated everything in sight.7 Standing down there, you really had no idea that you were at the bottom of the sea, and you might as well have been high up in the air with nothing but sky above you and below. When the sea was perfectly calm, you could catch sight of the sun, which looked like a purple flower with light streaming from its calyx.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Each little princess had her own plot in the garden, where she could dig and plant as she pleased. One arranged her flower bed in the shape of a whale; another thought it nicer to make hers look like a little mermaid; but the youngest made hers perfectly round like the sun,8 and she wanted nothing but flowers that shone just as red as it was. She was a curious child,9 quiet and thoughtful. While her sisters decorated their gardens with the wondrous objects they had gathered from sunken ships,10 she wanted only one thing apart from the rose-red flowers that were like the sun high above: a beautiful marble statue.11 The statue was of a handsome boy, chiseled from pure white stone, and it had landed on the bottom of the sea after a shipwreck. Next to it, the little princess had planted a crimson weeping willow12 that grew splendidly, draping its fresh foliage over the statue and touching the blue, sandy ocean bottom. It cast a violet shadow that, like its branches, was in constant motion. The roots and crown of the tree seemed always at play with each other, as if trying to kiss.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Nothing made the princess happier than learning about the human world up above.13 She made her grandmother tell her everything she knew about ships and towns, people and animals. She found it strangely beautiful that flowers up on the land had a fragrance—at the bottom of the sea they had none—and also that the trees in the forest were green and that the fish flying in the trees up there sang so clearly and beautifully that it was delightful to listen to them. Grandmother called the little birds fish, because otherwise the little sea princesses, never having seen a bird, would have no idea what she was talking about.

“When you turn fifteen,”14 Grandmother told them, “you’ll be allowed to swim up to the surface of the sea to sit on the rocks in the moonlight and watch the tall ships that pass by. You will also have the chance to see both forests and towns.” In the coming year, one of the sisters was going to turn fifteen, but the others—well, they were each born a year apart, and the youngest of them had to wait five whole years before she could venture up from the depths to see how things look up here. But each promised to tell the others what she had seen and what she had liked the most on that first visit. Their grandmother had not told them nearly enough, and there was so much that they still wanted to know.

No one longed to go up more than the youngest sister,15 the one who was so silent and thoughtful, and who also had the longest wait. Many a night she would stand at the open window and gaze up through the dark blue waters, where the fish were fluttering their fins and tails. She could see the moon and the stars, even though their light shone rather pale. Through the water they looked much bigger than they do to our eyes. If a black cloud passed beneath the stars, she knew that it was either a whale swimming overhead or a ship filled with many passengers. The people on board never imagined that a pretty little mermaid was waiting below,16 stretching her white arms up toward the keel of the ship.

As soon as the eldest princess turned fifteen, she was allowed to swim up to the surface.

When she returned, she had hundreds of things to report. The loveliest moment, she said, was lying on a sandbar close to the shore in the moonlight while the sea was calm. From there, you could see a city—its lights were twinkling like a hundred stars. You could hear the sounds of music17 and the commotion of carriages and people. You could see all the church towers and spires and hear their bells ringing. And because she could not get close to all those wonderful things, she longed for them all the more.

Oh, how the youngest sister drank it all in! And later that evening, while she stood at the open window gazing up through the dark blue waters, she thought of the big city with all its hustle and bustle, and she even fancied that she could hear the church bells18 ringing down to her.

The following year, the second sister was allowed to rise up through the water and swim wherever she liked. She reached the surface just as the sun was setting,19 and that, she said, was the loveliest sight of all. The whole sky was covered in gold, she declared, and the clouds—well, she just couldn’t describe how beautiful they were, with their crimson and violet hues, as they sailed over her head. Even more rapidly than the clouds, a flock of wild swans flew like a long white veil across the water toward the setting sun. The second sister swam off in that direction, but the sun sank, and its rosy glow was swallowed up by the sea and the clouds.

Another year passed, and the third sister swam up to the surface. She was the most daring of them all, and she swam upstream into a wide river that flowed into the sea. She could see beautiful green hills covered with grapevines20; castles and manors peeked out from magnificent woods; she could hear birds singing; and the sun was so hot that she often had to dive underwater to cool off her burning face. In a small cove she came upon a whole troop of human children, jumping around, quite naked, in the water. She wanted to play with them, but they were terrified and fled. Then a little black animal appeared. It was a dog, but she had never seen one before. The animal barked so ferociously at her that she became frightened and headed for the open sea. But she would never forget the magnificent woods, the green hills, and the darling children, who could swim even though they lacked tails.

The fourth sister was not nearly as daring. She stayed far out in the wild ocean and declared that it was the loveliest place of all. You could see for miles and miles around, and the sky overhead was like a big glass bell. She had seen ships, but at a distance so great that they looked like seagulls. Dolphins were sporting in the waves, and enormous whales spouted water so powerfully from their nostrils that they seemed to be surrounded by a hundred fountains.

And now it was the fifth sister’s turn. Since her birthday was in the winter, she saw things the others had not seen on their first outings. The sea had turned quite green, and there were large icebergs floating in it. Each one looked like a pearl, she said, and still they were larger than the church steeples built by humans.21 They appeared in the most fantastic shapes and glittered just like diamonds. She sat down on one of the largest, and all the ships seemed terrified, giving her a wide berth and sailing rapidly past. She stayed put, with the wind blowing through her long hair. Later that evening the sky became overcast. Thunder rolled and lightning flashed, and the dark waves lifted great chunks of ice high into the air, making them gleam when bolts of red lightning struck. The sails were taken in on all the ships, but amid the general horror and alarm, the mermaid remained serene on her drifting iceberg, watching blue lightning bolts zigzag down toward the glittering sea.

EDMUND DULAC

With his head only slightly above water and another wave ready to pound his body, the prince is rescued by the mermaid as she makes her way through a spectacular ocean of blues and foam, with a headdress of flowers that matches the element in which she lives.

When any one of the sisters reached the surface for the first time, she would be delighted by the many new and beautiful things up there. But as the princesses grew older and were allowed to go up as often as they liked, they began to lose interest. They longed to return home, and, after a month had passed, they declared that it was really much nicer down below. It was such a comfort to be at home.22

Many an evening, the five sisters would link arms to form a row and rise up out of the water. They had lovely voices,23 more beautiful than the sound of any human voice. If a storm was raging and they expected a shipwreck, the sisters would swim in front of the vessels and sing seductively about the delights found in the depths of the sea. They told the sailors not to be afraid to go down there, but the sailors never understood the words they sang. They thought they were hearing the howling of the storm. Nor did they ever see the beauty promised by the mermaids, because when their ships finally sank, the sailors drowned, and, by the time they reached the palace of the Sea King, they were dead.

When the sisters floated up, arm in arm, through the water in the evening, the youngest among them would be left behind, all alone, gazing after them. She would have cried, but mermaids cannot shed tears, and so they suffer even more than we do.

“Oh, if only I were fifteen years old,” she would say. “I know that I would come to love the world up there and all the people who live in it.”

Finally she turned fifteen.

“Well now, soon we’ll have you off our hands,” said the old dowager queen, her grandmother. “Come here, and let me dress you up like your sisters,” and she put a wreath of white lilies in her hair. Each flower petal was half a pearl, and the old woman clamped eight big oysters onto the princess’s tail to show her high rank.

“Ow! That really hurts,” said the little mermaid.

“Yes, beauty has its price,”24 the grandmother replied.

Oh, how the mermaid would have loved to shake off all that finery and remove that heavy wreath! The red flowers in her garden would have suited her so much better, but she did not dare make any changes. “Farewell,” she said, as she rose up through the water as swiftly and brightly as a bubble moves up to the surface.

The sun had just set when her head rose up through the waves, but the clouds were still gleaming like roses and gold. Up in the pale pink sky the evening star was shining bright and clear. The air was mild and fresh, and the sea was perfectly calm. A tall three-masted ship was drifting in the water, with only one sail hoisted because there was not so much as a breeze. The sailors could be seen taking it easy on the rigging and in the masts. There was music and singing on board,25 and when it grew dark, hundreds of colored lanterns were lit. They made it look like the flags of all nations were fluttering in the wind.

The little mermaid swam right up to the porthole of the cabin, and, every time a wave lifted her, she could see a throng of elegantly dressed people through the clear glass. Among them was a young prince, the handsomest person there, with big dark eyes. He could not have been more than sixteen. It was his birthday,26 and that’s why the festivities were taking place. When the young prince came out on the deck, where the sailors were dancing, more than a hundred rockets were shot into the air. They lit up the sky, making it look like daytime, and the little mermaid was so startled that she dove back down into the water. But she quickly popped her head back out again. It looked just as if all the stars up in heaven were falling down on her. Never before had she seen such fireworks. Huge suns were spinning around; magnificent fire fish went swooping through the blue air, and the entire display was reflected in the clear, calm waters below. The ship itself was so brightly illuminated that you could see even the smallest piece of rope—not to mention all the people there. How handsome the young prince looked! He shook hands with everyone, laughing and smiling as music filled the lovely night air.

It was growing late, but the little mermaid could not tear herself away from the ship or from the handsome prince. The colored lanterns had long been extinguished; the rockets were no longer being fired into the air; and the cannon volleys had stopped. Now you could hear the sea churning and groaning deep down below. Still the mermaid stayed on the surface, bobbing up and down so that she could look into the cabin.27 The ship began gathering speed as one sail after another caught the wind. The waves rose higher; heavy clouds darkened the sky; and lightning flashed in the distance. A dreadful storm was brewing, and so the crew took in the sails, while the great ship rocked and scudded through the raging sea. The waves rose higher and higher until they were like huge black mountains, threatening to bring down the mast. The ship dove like a swan28 between the waves and then rose again on their lofty, foaming crests. The little mermaid thought it must be fun to sail so fast, but the crew didn’t think so. The vessel groaned and creaked; the stout planks burst under the heavy pounding of the sea against the ship; and the mast snapped in two as if it were a reed. The ship rolled onto its side as water came rushing into the hold.

The little mermaid suddenly realized that the ship was in real danger. She herself had to watch out for the beams and bits of wreckage drifting in the water. For an instant it was so dark that she couldn’t see a thing, but then a flash of lightning lit everything up so that she could make out everyone on board. Now it was every man for himself. She was searching for the young prince and, just as the ship broke apart, she saw him disappear into the depths of the sea. At first she was overjoyed, for she believed that he would now live in her part of the world. But then she remembered that human beings could not survive underwater and that only as a dead man could he come down to her father’s palace. No, no, he mustn’t die! And so she darted in among the drifting beams and planks, oblivious to the danger of being crushed. She dove deep down and came right back up again among the waves, and at last she found the young prince, who barely had the strength to keep afloat in the stormy waters. His limbs were failing him; his beautiful eyes were shut; and he would surely have drowned if the little mermaid had not come to his rescue. She held his head above water and let the waves carry the two of them along.

By morning the storm had died down, and there was not a trace left of the ship. The sun, red and glowing, rose up out of the water and seemed to bring color back into the prince’s cheeks. But his eyes remained closed. The mermaid kissed his fine, high brow and smoothed back his wet hair. She thought that he looked just like the marble statue in her little garden. She kissed him again and made a wish that he might live.

Soon the mermaid saw land before her—lofty blue mountains topped with glittering white snow that made them look like nestling swans. Near the coast were lovely green forests, and close by was some kind of building, whether church or cloister she could not say. Lemon and orange trees were growing in the garden,29 and you could see tall palm trees by the gate. The sea formed a small bay at this point, and the water in it was quite calm, though very deep all the way up to the dunes, where fine white sand had washed ashore. The mermaid swam over there with the handsome prince, laid him down in the warm sunshine, and made a pillow for his head with the sand.

Bells began ringing in the large white building, and a group of young girls came walking through the garden. The little mermaid swam farther out from the shore, hiding behind some large boulders that rose out of the water. She covered her hair and chest with sea foam so that no one could see her. Then she watched to see who would come to help the poor prince.

It was not long before a young girl came by. She had a frightened look on her face, but only for a moment, and she quickly ran away to get help. The mermaid watched as the prince came back to life and began to smile at everyone around him. But there was no smile for her, because of course he had no idea that she had rescued him. After he was taken into the large building, she was overcome with sorrow and dove back into the water to return to her father’s palace.

The little mermaid had always been silent and thoughtful, but now she was even more so. Her sisters asked what she had seen during her first visit up above, but she did not say a word.

Many a morning and many an evening she swam up to the spot where she had left the prince. She saw the fruits in the garden ripen and watched as they were picked. She saw the snow melt on the peaks. But she never saw the prince, and so she always returned home, filled with even greater sorrow than before. Her one consolation was sitting in her little garden, with her arms wrapped around the beautiful marble statue30 that looked so like the prince. She gave up tending her flowers, and they grew into a kind of wilderness out over the paths, winding their long stalks and leaves around the branches of the trees until everything became quite gloomy.

Finally she could bear it no longer and told one of her sisters everything. The others learned about it soon enough, but no one else knew about it, except for a few other mermaids who didn’t breathe a word to anyone (apart from their closest friends). One of them knew who the prince was. She too had seen the festival held on board and knew where the prince came from as well as where his kingdom lay.

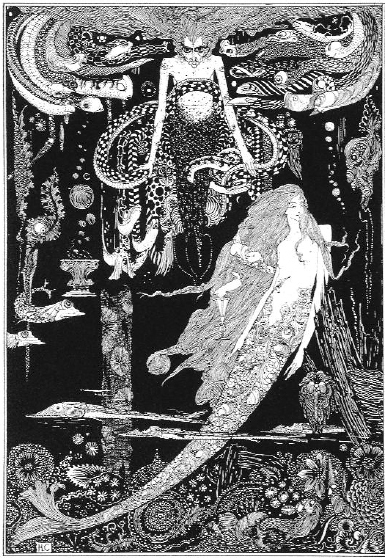

EDMUND DULAG

The little mermaid, eager to win the prince’s love, returns from the domain of the Sea Witch with the potion that will transform her body. The potion glows as she makes her way past sea creatures, a human skull, bones, and a gigantic octopus.

“Come, little sister!” the other princesses said. And with their arms on each other’s shoulders, they rose in one long row to the surface, right in front of where the prince’s castle stood.

The castle had been built with a gleaming, pale yellow stone, and it had grand marble staircases, one of which led straight down to the sea. Magnificent gilded domes rose above the rooftops, and between the pillars that surrounded the entire building stood lifelike marble statues. Through the clear glass of the tall windows you could see grand rooms decorated with sumptuous silk curtains and tapestries. The walls were covered with huge paintings that were a pleasure to behold. In the center of the largest room was a fountain that sprayed sparkling jets high up to the glass dome of the ceiling. The sun shone through it down on the water and on the beautiful plants growing in the large pool.

EDMUND DULAC

The prince, wearing oriental garments, leans up against a pillar and gazes down at the naked girl who has washed up on the marble steps to his palace. With only her long hair to cover her, the mermaid appears vulnerable in ways that she never was while at sea. In the distance appear the lights of the city that so entertained the mermaid’s sisters.

Now that the little mermaid knew where the prince lived, she spent many an evening and many a night at that spot. She swam much closer to the shore than any of the others dared. She even went up the narrow channel to reach the fine marble balcony that threw its long shadow across the water. Here she would sit and gaze at the young prince, who believed that he was completely alone in the bright moonlight.

Often in the evening, the little mermaid saw him go out to sea in his splendid vessel, with flags hoisted, to the strains of music. She peeked out from among the green rushes, and, when the wind caught her long silvery-white veil and people saw it, they just fancied it was a swan, spreading its wings.

On many nights, when the fishermen were out at sea with their torches, she heard them praising the young prince, and that made her all the more happy about saving his life on the day he was drifting half dead on the waves. And she remembered how she had cradled his head on her chest and how lovingly she had kissed him. But he knew nothing about any of this and never even dreamed she existed.

The little mermaid grew more and more fond of human beings and longed deeply for their company. Their world seemed far vaster than her own. They could fly across the ocean in ships and climb the steep mountains high above the clouds. And the lands they possessed, their woods and their fields, stretched far beyond where she could see. There was so much she would have liked to know,31 and her sisters weren’t able to answer all her questions. And so she went to visit her old grandmother, who knew all about the world above, which she quite rightly called the lands above the sea.

“If human beings don’t drown,” asked the little mermaid, “can they go on living forever? Don’t they die, as we do down here in the sea?”

“Of course they do,” the old woman replied. “They too must die, and their lifetime is even shorter than ours. We sometimes live for three hundred years, but when we cease to exist, we turn into foam on the sea.

We don’t even have a grave down here among our loved ones. We lack an immortal soul,32 and we shall never have another life. We’re like the green rushes. Once they’ve been cut, they stop growing. But human beings have a soul that lives on forever, even after their bodies have turned to dust. It rises up through the pure air until it reaches the shining stars. Just as we rise up from the sea to behold the lands of humans, they rise up to beautiful, unknown regions that we shall never see.”

“Why weren’t we given an immortal soul?” the little mermaid asked mournfully. “I would give all three hundred years of my life in return for becoming human for just one day and having a share in that heavenly world.”33

“You mustn’t waste your time worrying about these things,” the grandmother told her. “We’re really much happier and also better off than the human beings who live up there.”

“So then I’m doomed to die and to drift like foam on the sea, never to hear the music of the waves or see the lovely flowers and the red sun. Is there nothing I can do to gain an immortal soul?”

“No,” said the old woman. “Only if a human loved you so much that you meant more to him than his father and mother. If he were to love you with all his heart and soul and had the priest place his right hand in yours with the promise of remaining faithful and true here and in all eternity—then his soul would glide into your body and you too would share in human happiness. He would give you a soul and still keep his own. But that will never happen! Your fish tail, which we find so beautiful, looks hideous to people on earth. They don’t know any better. To be beautiful up there, you have to have those two clumsy pillars that they call legs.”

The little mermaid sighed and looked mournfully at her fish tail.

“Let’s celebrate,” said the old woman. “Let’s dance and be joyful for the three hundred years we have to live—that’s really quite time enough. After that we have plenty of time to rest in our graves. Tonight there will be a royal ball.”

That event was more splendid than anything we ever see on earth. The walls and ceiling of the great ballroom were made of thick, transparent crystal. Hundreds of colossal seashells, rose-red and grass-green, were lined up on all sides, each burning with a blue flame. They lit up the entire room and, by shining through the walls, also lit up the sea. Countless fish, large and small, could be seen swimming toward the crystal walls. The scales on some of them glowed with a purple-red brilliance; others appeared to be silver and gold. Down the middle of the ballroom flowed a wide rippling current, and in it mermen and mermaids were dancing to their own sweet songs. No human beings have voices so beautiful. The little mermaid sang more sweetly than anyone else, and everyone applauded her. For a moment there was joy in her heart, because she knew that her voice was more beautiful than any other34 on land or in the sea. But then her thoughts turned to the world above. She was unable to forget the handsome prince or her deep sorrow that she did not possess the same immortal soul humans possess. And so she slipped out of her father’s palace, and, while everyone inside was singing and making merry, she sat in her own little garden, feeling sad.

Suddenly the little mermaid heard the sound of a hunting horn echoing down through the water, and she thought: “Ah, there he is, sailing up above—the one I love more than my father or my mother, the one who is always in my thoughts and in whose hands I would gladly place my happiness. I would risk anything to win him and to gain an immortal soul. While my sisters are dancing away in Father’s castle, I’ll go visit the Sea Witch. I’ve always been terrified of her, but maybe she can give me some advice and help me out.”

The little mermaid left her garden and set out for the place where the Sea Witch lived, on the far side of the roaring maelstroms. She had never been over there before. There were no flowers growing there35 and no sea grass at all. Nothing was there but the bare, gray, sandy bottom of the sea, stretching right up to the maelstroms, where the water went swirling around like roaring mill wheels and pulled everything it got hold of down into the depths. She had to pass through the middle of those churning whirlpools in order to reach the domain of the Sea Witch. For a long stretch, there was no other path than one that took her over hot, bubbling mud—the witch called it her swamp.

The witch’s house lay behind the swamp in the middle of a strange forest. All the trees and bushes were sea polyps, half animal and half plant. They looked like hundred-headed serpents growing out of the ground. Their branches looked like long slimy arms, with fingers like slithering worms. Joint by joint from the root up to the very tip, they were constantly on the move, and they wound themselves tight around anything they could grab hold of from the sea, and then they would not let go.

The little mermaid was terrified and paused at the edge of the wood. Her heart was pounding with fear, and she came close to turning back. But then she remembered the prince and the human soul, and her courage returned. She tied her long flowing hair tightly around her head so that the polyps wouldn’t be able to grab hold of it. Then she folded her arms across her chest and darted forward like a fish shooting through the water, right in among the hideous polyps that reached out to snatch her with their nimble arms and fingers. She noticed how each of the sea polyps had caught something and was holding it fast with a hundred little arms that were like hoops of iron. The white skeletons of humans who had perished at sea and sunk down into the deep waters became visible in the arms of the polyps. Ship rudders and chests were held in their grip, along with the skeletons of land animals and—most horrifying of all—a small mermaid, whom they had caught and throttled.

She finally reached a great slimy clearing in the woods, where big, fat water snakes were romping in the mire and showing off their hideous, whitish-yellow bellies. In the middle of the clearing stood a house, built with the bones of shipwrecked human folk.36 There sat the Sea Witch,37 letting a toad feed from her mouth, exactly the way you can feed a canary with a lump of sugar. She called the hideous water snakes her little chickadees and let them cavort all over her big spongy chest.

“I know exactly what you want,” the Sea Witch said. “How stupid of you! But I’m going to grant your wish, and it will bring you misfortune, my lovely princess. You’re hoping to get rid of that fish tail and replace it with two stumps to walk on like a human being. You’re sure that the young prince will then fall in love with you, and then you can win him along with an immortal soul.”

And with that the witch let out such a loud, repulsive laugh that the toad and the water snakes tumbled to the ground and went sprawling. “You’ve come here just in time,” said the witch. “Tomorrow, once the sun is up, I wouldn’t be able to help you for another year. I shall prepare a potion for you. You will have to swim to land with it before sunrise, sit down on the shore, and swallow it. Your tail will then split in two and shrink into what human beings call pretty legs. But it will hurt. It will feel like a sharp sword passing through you. Everyone who sees you will say that you are the loveliest human child they have ever encountered. You will keep your graceful movements—no dancer will ever glide so lightly—but every step you take will make you feel as if you were treading on a sharp knife, enough to make your feet bleed.38 If you are willing to endure all that, I think I can help you.”

“Yes,” said the little mermaid, but her voice trembled. And she turned her thoughts to the prince and the prize of an immortal soul.

“Think about it carefully,” said the witch. “Once you take on the form of a human, you can never again be a mermaid. You’ll never be able to swim back through the water to your sisters or to your father’s palace. The only way you can acquire an immortal soul is to win the prince’s love and make him willing to forget his father and mother for your sake. He must cling to you always in his thoughts and let the priest join your hands to become man and wife. If the prince marries someone else, the morning after the wedding your heart will break, and you will become foam on the waves.”

“I’m ready,” said the little mermaid, and she turned pale as death.

“But first you will have to pay me,” said the witch. “And it’s not a small thing that I’m demanding. You have a voice more beautiful than anyone else’s down here at the bottom of the sea. You may be planning to charm the prince with it, but you are going to have to give it to me. I want the dearest thing you possess in exchange for my precious potion. You see, I have to add my own blood to make sure that the drink will be as sharp as a double-edged sword.”

“But if you take my voice away,” said the little mermaid, “what will I have left?”

“Your lovely figure,” said the witch, “your graceful movements, and your expressive eyes. With all that you can easily enchant a human heart. Well, where’s your courage? Stick out your little tongue and let me cut it off in payment.39 Then you shall have your powerful potion.”

“So be it,” said the little mermaid, and the witch placed her cauldron on the fire to brew the magic potion.

“Cleanliness above everything else,” she said, as she scoured the cauldron with the water snakes, which she had tied into a large knot. Then she made a cut in her chest and let her black blood ooze out. The steam from the cauldron created strange shapes, terrifying to behold. The witch kept tossing fresh things into the cauldron, and when the brew began to boil, it sounded like a crocodile weeping. At last the magic potion was ready, and it looked just like clear water.40

“There you go!” said the witch as she cut out the little mermaid’s tongue. 41 Now she was mute and could neither speak nor sing.

“If the polyps try to grab you on your way out through the woods,” said the witch, “just throw a single drop of this potion on them,42 and their arms and fingers will burst into a thousand pieces.” But the little mermaid didn’t need to do that. The polyps shrank back in terror when they caught sight of the luminous potion glowing in her hand like a glittering star. And so she passed quickly through the woods, the marsh, and the roaring whirlpools.

The little mermaid could now see her father’s palace. The lights in the ballroom were out, and everyone was probably fast asleep by now. But she did not dare to go take a look, for she could not speak and was about to leave them forever. Her heart was aching with sorrow. She stole into the garden, took a flower from the beds of each of her sisters, blew a thousand kisses toward the palace, and then swam up through the dark blue waters.

The sun had not yet risen when she caught sight of the prince’s palace and made her way up the beautiful marble steps. The moon was shining clear and bright. The little mermaid drank the bitter, fiery potion, and it felt to her as if a double-edged sword was passing through her delicate body. She fainted and fell down as if dead.

When the sun came shining across the sea, it woke her up. She could feel a sharp pain, but right there in front of her stood the handsome young prince. He stared at her so intently with his coal-black eyes that she cast down her own and saw that her fish tail was gone.43 She had as charming a pair of white legs as any young girl could want. But she was quite naked, and so she wrapped herself in her long, flowing hair. The prince asked who she was and how she had found her way there, and she could only gaze back at him tenderly and sadly with her deep blue eyes, for of course she could not speak. Then he took her by the hand and escorted her into the palace. Every step she took, as the witch had predicted, made her feel as if she were treading on sharp knives and piercing needles,44 but she willingly endured it. Hand in hand with the prince, she moved as lightly as a bubble. He and everyone else marveled at the beauty of her graceful movements.

She was given costly dresses of silk and muslin after she arrived. She was the most beautiful creature in the palace, but she was mute and could not speak or sing. Enchanting slave girls dressed in silk and gold came out and danced before the prince and his royal parents. One sang more beautifully than all the others, and the prince clapped his hands and smiled at her.45 The little mermaid felt sad, for she knew that she herself had once sung far more beautifully. And she thought, explain so much they would like to. I don’t know that I felt particularly misunderstood but the threat is always there for children that they will be inadequate, possibly even speechless, when it’s urgent that they be heard. So the idea that the mermaid, for love, would volunteer to lose her voice and thus yield up any chance to make her case—ah, this was so terrible to me I could hardly look it in the eye. And so, of course, I looked and looked” (Brown, 55). “Oh, if only he knew that I gave my voice away forever in order to be with him.”

The slave girls performed a graceful, swaying dance to the most sublime music. And the little mermaid raised her beautiful white arms, lifting herself up on the tips of her toes, and floating across the floor, dancing as no one had ever danced before. She looked more and more lovely with every step, and her eyes spoke more deeply to the heart than the songs of the slave girls.

Everyone was enraptured, especially the prince, who called her his little foundling. She kept on dancing, even though it felt like she was treading on sharp knives every time her foot touched the ground. The prince insisted that she must never leave him, and she was allowed to sleep outside his door on a velvet cushion. 46

The prince had a page’s costume made for her47 so that she could ride on horseback with him. They galloped through fragrant woods, where green boughs brushed her shoulders and little birds sang among the fresh, new leaves. She climbed with the prince to the tops of high mountains and, although her delicate feet began to bleed and everyone could see the blood, she just laughed and followed the prince until they could look down and see clouds fluttering in the air like flocks of birds on their way to distant lands.

At night, back in the prince’s palace, when everyone in the household was fast asleep, the little mermaid would go over to the marble steps and cool her burning feet by standing in the icy seawater. And then she would think about those who were living down there in the deep.

One night her sisters rose up and sang mournfully as they floated arm in arm on the water. She beckoned to them, and they recognized her and told her how unhappy she had made them all. From then on, they started visiting her every night, and one night she even saw, far off in the distance, her old grandmother, who had not been up to the surface for many years, and she also saw the old Sea King, wearing his crown on his head. They both stretched their arms out toward her, but they did not dare to venture as close to the shore as her sisters.

With each passing day, the prince grew fonder of the little mermaid. He loved her as one loves a dear, sweet child, and it never even occurred to him to make her his queen. And yet she had to become his wife or else she would never receive an immortal soul. On his wedding morning, she would dissolve into foam on the sea.

“Do you care for me more than anyone else?” the little mermaid’s eyes seemed to ask when he took her in his arms and kissed her lovely brow.

“Yes, you are more precious to me than anyone else,” said the prince, “for you have the kindest heart of anyone I know. And you are more devoted to me than anyone else. You remind me of a young girl I once met, but shall probably never see again. I was in a shipwreck, and the waves cast me ashore near a holy temple, where several young girls were performing their duties. The youngest of them found me on the beach and saved my life. I saw her just twice. She is the only one in the world whom I could ever love.48 But you look so much like her that you have almost driven her image out of my mind. She belongs to the holy temple, and my good fortune has sent you to me. We will never part!”

“Ah, little does he know that it was I who saved his life,” thought the little mermaid. “I carried him across the sea to the temple in the woods, and I waited in the foam for someone to come and help. I saw the beautiful girl that he loves better than he loves me.” And the mermaid sighed deeply, for she did not know how to shed tears. “He says the girl belongs to the holy temple and that she will therefore never return to the world. They will never again meet. I will stay by his side and can see him every day. I will take care of him and love him and devote my life to him.”

Not long after that, there was talk that the prince was going to marry and that his wife would be the beautiful daughter of a neighboring king. And that’s why he was rigging out a splendid ship. They said that he was going to pay a visit to the lands of a neighboring kingdom, but in fact he was going to visit the neighboring king’s daughter. He was taking a large entourage with him. The little mermaid shook her head and laughed. She knew the prince’s thoughts far better than anyone else.

“I shall have to go,” he told her. “I must visit this beautiful princess—my parents insist. But they would never force me to bring her back here as my wife. I could never love her. She’s not at all like the beautiful girl in the temple, whom you resemble. When I have to choose a bride someday, it is much more likely to be you, my quiet little orphan child with your expressive eyes.” And he kissed the mermaid’s red lips, played with her long hair, and laid his head on her heart so that she began to dream of human happiness and an immortal soul.

“You are not at all afraid of the sea, are you, my dear quiet child?” he asked, when they stood on board the splendid ship that was carrying them to the neighboring kingdom. He told her about powerful storms and calm waters, about the strange fish in the deep, and what divers had seen down there. She smiled at his tales, for she knew better than any one else about the wonders at the bottom of the sea.

In the moonlit night when everyone was asleep but the helmsman at his wheel, the little mermaid stood by the railing of the ship and gazed down through the clear water. She thought she could see her father’s palace, and there at the top of it was her old grandmother, a silver crown on her head as she stared up through the turbulent currents at the keel of the vessel. Then her sisters rose up to the surface and looked at her with eyes filled with sorrow, wringing their white hands. She beckoned to them and smiled and would have liked to tell them that she was happy and that all was going well for her. But the cabin boy came up just then, and the sisters dove back down, and the boy thought that the whiteness he had seen was nothing but foam on the water.

The next morning the ship sailed into the harbor of the neighboring king’s magnificent capital. All the church bells were ringing, and trumpeters blew a fanfare from the towers. Soldiers saluted with flying colors and flashing bayonets. Every day brought a new festival. Balls and banquets followed one another, but the princess had not yet appeared. It was reported that she had been raised and educated in a holy temple, where she was learning all the royal virtues. At last she appeared.

The little mermaid was eager for a glimpse of her beauty, and she had to admit that she had never seen a more enchanting person. Her delicate skin glowed with health, and her warm blue eyes shone with deep sincerity from behind her long, dark lashes.

“It’s you,” said the prince. “You’re the one who rescued me when I was lying half dead on the beach.” And he reached out and drew his blushing bride toward him.49 “Oh, I’m really overjoyed,” he said to the little mermaid. “The best thing imaginable—more than I ever dared hope for—has been given to me. My happiness is sure to give you pleasure, for you are fonder of me than anyone else.” The little mermaid kissed his hand, and she could feel her heart breaking. The day of the wedding would mean her death, and she would turn into foam on the ocean waves.

All the church bells were ringing when the heralds rode through the streets to proclaim the betrothal. Perfumed oils were burning in precious silver lamps on every altar. The priests were swinging the censers, while the bride and bridegroom joined hands to receive the blessing of the bishop. Dressed in silk and gold, the little mermaid was holding the bride’s train, but her ears could not take in the festive music, and her eyes never saw the holy rites. All she could think about was her last night on earth and about everything in this world that she had lost.

That same evening, bride and bridegroom went aboard the ship. Cannons roared, flags were waving, and in the center of the ship a sumptuous tent of purple and gold had been raised. It was strewn with luxurious cushions, for the bridal couple was to sleep there during the calm, cool night. The sails swelled in the breeze, and the ship glided lightly and smoothly across the clear seas.

When it grew dark, colored lanterns were lit, and the sailors danced merrily on deck. The little mermaid could not help but think of that first time she had come up from the sea and gazed on just such a scene of splendor and joy. And now she joined in the dance, swerving and swooping as lightly as a swallow does to avoid pursuit. Cries of admiration greeted her from all sides. Never before had she danced so elegantly. It was as if sharp knives were cutting into her delicate feet, but she didn’t notice, for the pain in her heart was far keener. She knew that this was the last night she would ever see the prince, the man for whom she had forsaken her family and her home, given up her beautiful voice, and suffered hours of agony without his suspecting a thing. This was the last evening that she would breathe the same air that he did or gaze into the deep sea and up at the starry sky. An eternal night, without thoughts or dreams, awaited her, since she did not have a soul and would never win one. All was joy and merriment on board until long past midnight. She laughed and danced with the others although the thought of death was in her heart. The prince kissed his lovely bride, while she played with his dark hair, and arm in arm they retired to the magnificent tent.

The ship was now hushed and quiet. Only the helmsman was standing there at his wheel. The little mermaid was leaning on the railing with her white arms and looking to the east for a sign of the rosy dawn. She knew that the first ray of sunlight would mean her death. Suddenly she saw her sisters rising up from the sea. They were as pale as she, but their beautiful long hair was no longer blowing in the wind—it had been cut off.

“We gave our hair to the witch,” they said, “so that she would help save you from the death that awaits you tonight. She gave us a knife—take a look! See how sharp it is? Before sunrise you must plunge it into the prince’s heart.50 Then, when his warm blood spatters on your feet, they will grow back together to form a fish tail, and you will be a mermaid again. You can come back down to us in the water and live out your three hundred years before being changed into dead, salty sea foam. Hurry up! One of you will die before the sun rises. Our old grandmother has been so grief-stricken that her white hair started falling out, just the way ours fell to the witch’s scissors. Kill the prince and come back to us! Hurry—look at the red streaks in the sky. In a few minutes the sun will rise, and then you will die.” And with a strange, deep sigh, they sank down beneath the waves.

The little mermaid drew back the purple curtain of the tent, and she saw the lovely bride sleeping with her head on the prince’s chest. She bent down and kissed his handsome brow, then looked at the sky where the rosy dawn was growing brighter and brighter. She gazed at the sharp knife in her hand and fixed her eyes again on the prince, who was whispering the name of his bride in his dreams. She was the only one in his thoughts. The little mermaid’s hand began to tremble as she took the knife—then she flung it far out over the waves. The water turned red where it fell, and it looked as if blood was oozing up, drop by drop, through the water. With one last glance at the prince from eyes half-dimmed, she threw herself from the ship into the sea51 and felt her body dissolve into foam.

And now the sun came rising up from the sea. Its warm and gentle rays fell on the deadly cold sea foam, but the little mermaid did not feel as if she were dying. She saw the bright sun and realized that there were hundreds of lovely transparent creatures hovering over her. Looking right through them, she could see the white sails of the ship and rosy clouds up in the sky. Their voices were melodious, but so ethereal that human ears could not hear them, just as mortal eyes could not behold them. They soared through the air on their own lightness, with no need for wings. The little mermaid realized that she had a body like theirs and that she was rising higher and higher out of the foam.

“Where am I?” she asked, and her voice sounded like that of the other beings, more ethereal than any earthly music.

“Among the daughters of the air,”52 they replied. “Mermaids do not have an immortal soul, and they can never have one without gaining the love of a human being. Eternal life depends on a power outside them. The daughters of the air do not have immortal souls either, but through good deeds they can earn one for themselves. We can fly to the hot countries, where sultry, pestilential air takes people’s lives. We bring cool breezes. We carry the fragrance of flowers through the air and send relief and healing. Once we have struggled to do all the good we can in three hundred years, immortal souls are bestowed on us, and we enjoy the eternal happiness humans find. You, my dear little mermaid, have struggled with all your heart to do what we do. You have suffered and endured and now you have been transported to the world of the spirits of the air. Through good deeds, you too can earn an immortal soul53 in three hundred years.”

The little mermaid lifted her transparent arms toward God’s sun, and for the first time she could feel tears coming to her eyes.

Over by the ship, there were sounds of life, with people bustling about. The mermaid could tell that the prince and his beautiful bride were searching for her. With deep sorrow, they were staring out at the pearl-colored foam, as if they knew that she had thrown herself into the waves. Unseen, the mermaid kissed the bride’s forehead, smiled at the prince, and then, with the other children of the air, rose up into the pink clouds that were sailing across the skies.

EDMUND DULAC

Bearing a distinct resemblance to Ophelia, the little mermaid, now wearing splendid, regal garments, returns to her element and believes that she is about to become foam, while in the distance the sun is rising, warming the foam.

“In three hundred years we will soar like this into the heavenly kingdom.”

“And we may arrive there even sooner,” one of her companions whispered. “Invisible to human eyes, we float into homes where there are children. For every day we find a good child who makes his parents happy and deserves their love, God shortens our time of trial. Children never know when we are going to fly into their rooms, and if we smile with joy when we see the child, then a year is taken away from the three hundred. But a mean or naughty child makes us shed tears of sorrow, and each of those tears adds another day to our time of trial.”55

ARTHUR RACKHAM

1. The Little Mermaid. In constructing his aquatic character, Andersen drew on varied strands of both folkloric and literary traditions about fairy creatures—selkies, nymphs, nixies, undines—who appear on earth, marry mortals, but can remain on land only under certain conditions. Stories about selkies, seals who bask seductively in the sun on outlying rocks and who have the power to turn into beautiful humans, circulate broadly on the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland. Nixies are akin to the Greek sirens, who lure mortals to their death, but sirens have a birdlike appearance rather than pisciform features.

It is not clear exactly when sirens evolved into mermaids, losing their ornithomorphic features to acquire fish tails (Dundes, 56). A female siren in the form of a beautiful woman with the tail of a fish famously appears in Heinrich Heine’s “Loreley,” a poem that recounts the death of fishermen who drown when distracted from dangerous reefs by the Loreley’s enchanting song. Melusine, or Melusina, another figure of European legends and folklore, is usually represented as a woman, sometimes with wings, sometimes as a serpent or fish from the waist down.

Andersen was familiar with Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s short story “Undine” (1811), a tale about a knight who falls in love with the daughter of the King of the Sea and betrays her. Fouqué’s work inspired a host of ballets and operatic tales about the beautiful femme fatale who cannot speak about her origins: Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, Dvořák’s Rusalka, and Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Andersen did not approve of Fouqué’s ending and wrote to a friend on February 11, 1837, shortly after completing his own story: “I have not . . . let the mermaid’s acquisition of an immortal soul depend on an alien creature, upon the love of a human being. I’m sure that would be wrong! It would depend rather a lot on chance, wouldn’t it? I won’t accept that sort of thing in this world. I have permitted my mermaid to follow a more natural, a more divine path.”

Andersen was also familiar with mermaid tales by the Danish writers Ingemann and Oehlenschläger, as well as Bournonville’s ballet La Sylphide, which was performed in Copenhagen in 1836. His “Little Mermaid” in turn inspired a host of nineteenth-century tales and twentieth-century films. Oscar Wilde’s “The Fisherman and His Soul” (1891) and H.G. Wells’s The Sea Lady (1902) were both influenced by Andersen’s tale. In more recent times, the mermaid has become what Susan White describes as “a pervasive cinematic symbol of the girl’s difficult rite of passage to womanhood” (White, 186), with films like I Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987), Mermaids (1990), and La Petite Sirène (1990) taking up painful “growth” experiences. Splash, starring Tom Hanks and Daryl Hannah, adds many modern twists to the tale, with an ending that pays tribute to the attractions of life underwater.

The mermaid, as Dorothy Dinnerstein points out in her landmark study of human sexual arrangements, Mermaids and Minotaurs (1976), has traditionally been framed as a “seductive and impenetrable female representative of the dark and magic underwater world from which our life comes and in which we cannot live.” Drawing voyagers into an aquatic world linked with the sinister and irrational, she “lures them to their doom” (Dinnerstein, 5). But Andersen’s little mermaid is less siren than innocent child (the prince repeatedly refers to her as a foundling and child) trying to acquire a soul. She is driven more by the desire for a soul than by love for the prince.

The great granddaughter of Jonas Collin (Andersen’s benefactor in Copenhagen) danced the role of the mermaid in a ballet production of 1913. A patron of the arts gave to the city of Copenhagen a statue of a mermaid after seeing her dance. The head has been sawed off twice, once in 1964, and again in 1998. A group called the Radical Feminist Faction claimed responsibility for the act, apparently because the statue was seen as a symbol of women’s abject willingness to sacrifice everything for the love of a man.

EDMUND DULAC

Holding a shell in his hand and perched on a rock with a lobster, the Sea King feeds the subjects in his aquatic domain. His crown of coral and shells and his sparkling bracelets and necklaces are the signs of his regal status.

In turning an adult legend about fairies and mortals into a tale for children, Andersen also changed the story’s character, placing such social values as love, duty, and the transcendent value of self-sacrifice in the foreground. In her memoir Leaving a Doll’s House, actress Claire Bloom reminisces about the “sound of Mother’s voice as she read to me from Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’ and ‘The Snow Queen.’ ” Although the experience of reading produced “a pleasurable sense of warmth and comfort and safety” for Bloom, she also emphasizes that “these emotionally wrenching tales . . . instilled in me a longing to be overwhelmed by romantic passion and led me in my teens and early twenties to attempt to emulate these self-sacrificing heroines” (Bloom, 9).

Andersen scholars frequently point out that the tale was begun the day after Jonas Collin’s son Edvard married, and that “The Little Mermaid” could be an expression of the writer’s anguish that his friend had an attachment to a woman with whom he could never compete.

2. Far out at sea. Here, Andersen calls attention to the performative aspect of the story. The phrase “far out at sea” presumes that narrator and audience are on dry land and need to be plunged, through their imaginations, to the depths of the sea. The sea bottom is represented as a world completely separated from the world of humans, at a depth that makes it completely inaccessible. The proliferation of adjectives—“blue,” “clear,” “pretty,” and “pure”—all point to an Atlantis-like beauty and grandeur, even if the sea kingdom remains a pagan site, though its distance from the human world is, ironically, measured in church steeples. (The early introduction of church steeples is significant, for church bells, as we shall see, play a significant role in the story.)

Water appears as the source of life in nearly all creation myths, and its healing properties are celebrated in many cultures. But bodies of water are also the site of death, the source of pollution as well as cleansing, the home to beautiful creatures as well as hideous monsters, the site of drowning as well as baptism and rejuvenation. “Bodies of water,” one commentator on “The Little Mermaid” points out, “are . . . emotionally charged in the human psyche, and the mythical creatures who reside in them become variously inflected with their power, with their potent blend of threat and allure” (Easterlin, 259).

3. The sea people live down there. The realm of the sea folk is described as a benign paradise, something of a parallel universe to the human world (with fish instead of birds, and so on) but with more natural beauty and the leisure to enjoy it. Disney’s little mermaid, Ariel, inhabits a kingdom where the creatures living under the sea seem to do little more than sing and dance.

4. Now you mustn’t think for a moment. Note the conversational tone that is taken right from the start as the narrator establishes himself as the source of authority on sea folk and vouches for their existence. The (presumably human) narrator seems to have an unbiased attitude toward merfolk. As James Massengale points out, “his narrative ‘camera’ . . . focuses upon the youngest of the Merking’s daughters, and from that point it essentially never leaves her” (“The Miracle and A Miracle in the Life of a Mermaid,” 556–57). His stance appears to be neutral and undogmatic, for he is both enchanted by the beauty of the undersea world and committed to the notion of Christian salvation. It is important to remember that he uses the term “we” to designate humans, and he reveals the spiritual shortcomings of the Sea King’s world in the course of telling the story.

5. the castle of the Sea King. The underwater domain of the Sea King is an aesthetic paradise, a site where art (song, dance, and spectacle) meets natural beauty. Still, certain hierarchical distinctions, such as the number of oysters worn on the tail of the Sea King’s mother, make it clear that this is no social utopia.

6. But like all the others, she had no feet. Despite the exceptional beauty of the undersea region, a clear hierarchical relationship begins to be established between humans and sea folk, in which humans are seen as superior. The “but” betrays a bias again the sea folk, who lack the feet that figure so importantly in Andersen’s tales. Note also the repeated allusion to movement in the seascape. It is, however, a movement that imitates life rather than capturing it—everything moves “as if” it were alive. Sheldon Cashdan, author of The Witch Must Die, points out that as long as the little mermaid lacks legs, she remains unappealing to the prince: “A tail is an impediment when it comes to making love” (Cashdan, 165). But in ancient lore, the fish tail was a symbol of the mermaid’s power rather than her inferiority, and the mirror she held was a symbol of the sea rather than a sign of her vanity.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

7. A wondrous blue glow permeated everything in sight. Blue and red are the dominant colors in the narrative, the one associated with the depths of the sea and the heights of the heavens, the other linked with sunlight, passion, suffering, and blood. Even the little mermaid is first introduced as having skin as delicate as a rose leaf and eyes as blue as the sea. Gold too makes frequent appearances and is often connected with gleaming, glittering surface beauty. It is possible that Andersen, who spent many months in Italy, may have been influenced by the blues, reds, and golds in Italian paintings of the Madonna and child.

8. the youngest made hers perfectly round like the sun. The little mermaid’s aspirations are clear early on. She strives to transcend her aquatic nature and reach a higher stage of existence. In the end, she does indeed become an airborne creature. Her two sisters remain wedded to marine life in choosing the shapes for their gardens (whales and mermaids), while she moves out of her own realm and her own being to represent something otherworldly (the sun). Focused on what she can perceive of the other world—the sun shining through the waters and the ships creating shadows as they pass by overhead—she exhibits desires that deviate from what is expected in the undersea realm.

9. She was a curious child. The little mermaid is “curious” in the double sense of the term—intellectually adventurous and also something of an oddity. She is (somewhat like Andersen himself) upwardly mobile, intent on gaining knowledge of the world above, but also destined to remain a misfit among the sea folk with her desire to inhabit land, and an anomaly among humans with her lack of a soul. As James Massengale points out: “She grows a different garden. She longs for church bells she has never heard. She saves the Prince instead of watching him drown. She pines for him instead of forgetting him as an inaccessible or inimical being. She refuses to follow her grandmother’s mermaid-rules. She denies her Mermaid tendencies and her Mermaid shape, and makes a contract with the Sea Witch, which causes her to destroy her body and abandon her kingdom forever, in order to balance on the keen edge of a possibility of becoming human” (Massengale, 568).

10. wondrous objects they had gathered from sunken ships. The sisters’ mania for collecting is transferred in the Disney film to Ariel, who hoards and fetishizes artifacts of civilization (forks, combs, and so on) as a sign of her desire to live with humans. If Andersen’s little mermaid is inspired by church bells she has never heard and is driven by longing for the hustle and bustle of the big city (as was the young Andersen), Ariel—as is appropriate for a Disney character—becomes a slave to commodity fetishism.

11. a beautiful marble statue. If Andersen’s mermaid has a fetishized object, it is the marble statue, which becomes the target of chaste feelings as well as erotic longings. Many of Andersen’s stories feature inanimate figurines such as the tin soldier and ballerina in “The Steadfast Tin Soldier.” The shepherdess and the chimney sweep, in the story of that title, are also both made of marble.

Stories of animated statues can be documented in folklore and literature from all over the world. The two most famous tales are of Pygmalion and Don Juan. The statue of the boy, rescued from a shipwreck, has none of the haunting qualities found in other nineteenth-century literary statues, for example, those in Prosper Mérimée’s “Venus of Ile” or Henry James’s “Last of the Valerii.”

Andersen’s “Psyche” works within a Romantic literary tradition of statues and portraits of women so disturbingly lifelike that they produce uncanny effects and (often) tragic endings. Inspired by the beauty of a real-life woman, the unnamed artist in Andersen’s “Psyche” transforms a marble stone into her likeness. He falls madly in love with the statue, which is as “perfect as God’s own image of the young girl.” The little mermaid, by contrast, seeks the human incarnation of the marble statue that she has enshrined in her garden.

12. a crimson weeping willow. Note that the undersea world lacks green and that red and blue are the colors used for all living things. A traditional symbol of mourning that is refigured by Andersen in sentimental terms (the roots and the crown are always “trying to kiss each other”), the presence of the tree nonetheless hints at a tragic ending. The little mermaid’s garden contains elements that prefigure her future: the sun-shaped flower bed that stands for the light of the human world and for redemption, the statue that is a double of the prince, and the weeping willow that anticipates her pain and sorrow in the world above.

13. learning about the human world up above. It is through stories, told by one generation to the next, that the little mermaid first hears about the world of humans. The grandmother’s descriptions of beauty are what attract the attention of her granddaughter. The aroma of the flowers, the green of the trees, and the song of the birds together create olfactory, visual, and acoustic pleasures. One feminist critic points out that “the sea world is rendered either invisible or mythic while the land world is endowed with cultural validity” (Sells, 178).

14. “When you turn fifteen.” Andersen himself was just fourteen years old when he left Odense in 1819 to seek his fortune in Copenhagen. Fifteen marks the transition from childhood to adulthood, to a state of physical and emotional maturity. At that age, the mermaids are viewed as sensible enough to take a look at the upper world without being seduced by the temptation to see more. The grandmother emphasizes that they can see the world of humans only by moonlight, presumably because the sunlit upper world would be too tantalizing. It is only the “bolder” of the sisters who goes to the world of humans in daylight. Although the little mermaid is fifteen and undergoes a rite of passage from child to woman, she remains childlike even after her birthday.

15. No one longed to go up more than the youngest sister. Curiosity is once again emphasized as the defining feature of the little mermaid and as the trait that singles her out from others. A hybrid creature to begin with, she longs with all her being—mind as well as body (think of those outstretched arms as she watches ships sailing above her)—to attain a higher state even while she lives underwater.

16. a pretty little mermaid was waiting below. The term “little mermaid” is used for the first time in the story. Here, the term “little” is linked with beauty and youth. But with such phrases as “you poor little mermaid,” the diminutive stature soon comes to be associated with unhappiness, longing, and suffering.

17. You could hear the sounds of music. The sisters, unable to communicate with humans through their song, turn into spectators and listeners who are eager to take in sights and sounds from the world above. They become “voyeurs who gleefully consume the ephemeral sights and sounds of human life as spectacles of the first rank” (Alter and Koepnick, 7). The eldest of the six sisters finds the main appeal of that domain in sound. For her, music, the sounds of everyday life, and the ringing of church bells are “wondrous things” that produce a desire to inhabit the human world.

The church bells, more than any other sound, tellingly serve as the most powerful lure to enter the world of humans for this sister. The many distractions of urban life—artificial lights, swift carriages, hectic activity—form a stark contrast to the tranquillity of the mermaid’s garden and to the serenity of the churches in which the bells are ringing. The city nonetheless remains a site of fascination, with sonic and visual attractions that are a source of deep longing.

18. she even fancied that she could hear the church bells. Oddly, the little mermaid longs for the sound of the church bells, even though she has never heard them and has no understanding of their symbolic function.

19. She reached the surface just as the sun was setting. The powerful allure of the sun becomes evident upon the second sister’s visit. She swims in the direction of the sunset, only to find that the orb has disappeared. This sister visits the earth at a time of transition from day to night, and it is no accident that she sees a flock of white swans during her expedition. For Andersen, swans are creatures that have transcended a state of gawky awkwardness to become, as in “The Ugly Duckling,” incarnations of majestic splendor. Like butterflies, the romantic symbol par excellence for transformation, swans are able to metamorphose into a more noble physical state. The transformation of the little mermaid from sea creature to mermaid in human form to a creature of the air reflects Andersen’s constant engagement with mutability and changes in identity.

20. beautiful green hills covered with grapevines. Andersen’s landscapes are filled with vivid sights, sounds, and aromas. The third sister sees nature’s beauty and also discovers how humans have entered it to cultivate it (with grapevines), build residences (castles and manors), and produce children. The mutual animosity (based on fear driven by lack of familiarity) between the two worlds becomes evident when the mermaid terrifies the children and the dog terrifies the mermaid.

21. they were larger than the church steeples built by humans. Again church steeples are invoked, even in the icy landscape visited by the fifth sister. The green ocean, icebergs that glitter like diamonds, black waves, and red and blue lightning create a colorful spectacle of sublime delights. Here again, the conflicts between humans and merfolk are deepened, for it becomes clear that what the mermaid perceives as a source of visual pleasure is a real danger to the sailors. Humans and merfolk cannot coexist under conditions in which what is beautiful for one group is lethal for the other.

22. It was such a comfort to be at home. All but the little mermaid remain homebodies. Only she will find that familiarity does not breed contempt and that the world above offers more than the visual and acoustic attractions so appealing to her sisters.

23. they had lovely voices. The sisters have powerful vocal talents, but their “enchanting” song cannot accomplish its aim of drawing the attention of humans sailing by. No matter how beautifully the mermaids sing, the sailors cannot be seduced by them, for they hear nothing but the sounds of a storm. Andersen intensifies the divide between merfolk and humans by showing that song and storm coexist, but what is (beautiful) song to merfolk is (fatal) storm to humans.

Having a voice and the ability to display its artistry figure importantly in a tale that celebrates spectacle and sound. That the little mermaid later loses her voice reveals the drawbacks of the exchange made with the Sea Witch. While the mermaid’s voice has emotive strength, it is linked above all with artistic expression. It is what makes her appealing to both merfolk and humans.

24. “Yes, beauty has its price.” The costuming scene with grandmother and mermaid prefigures the later scene of mutilation with Sea Witch and mermaid. The grandmother, oddly, dresses the little mermaid up for a voyage that is not intended for exhibitionistic purposes—the little mermaid is rising up in order to look at others. Even in these preliminary preparations, the little mermaid learns that beauty and the power to attract exact a toll.

25. There was music and singing on board. The sound of music and the light of lanterns draw the little mermaid to the activity on board the ship. Like her sisters, she is attracted to the music of humans, which does not seem to have the seductive, treacherous overtones of the songs sung by the sisters. The songs and merriment on board inspire her wish to join the human throng.

26. It was his birthday. Note that the little mermaid and the Prince share a birthday, suggesting that they could be soul mates. The Prince is most likely either exactly her own age or a year older, since he could not have been more than sixteen years old.

27. bobbing up and down so that she could look into the cabin. The little mermaid’s curiosity about human beings draws her to the world of the prince. Fascinated by what is above the surface, by the unknown, and by the forbidden, she shows an investigative curiosity lacking in many fairy-tale heroines but shared with biblical figures like Eve and Lot’s wife.

28. the ship dove like a swan. The comparison suggests that the vessel is a graceful ship, with a nobility and beauty resembling that of a creature that Andersen repeatedly frames as aristocratic. The mountains in the prince’s domain are also described as having the appearance of “nestling swans.” The little mermaid will perform the same graceful movements as the swanlike ship when she rescues the prince, diving into the waves and darting through the ship’s wreckage. Andersen himself has been described as a “water fanatic” who loved to “throw himself into the waves so he could then rise up again—as he said—with a feeling of being reborn and see the world from a whole different perspective” (Jens Andersen, 197).

29. Lemon and orange trees were growing in the garden. The prince’s domain is clearly in southern regions. The architecture of the buildings suggests a southern European locale, and it is likely that Andersen had Italy in mind. He had been deeply impressed by the beauty of the Italian countryside and wrote with enthusiasm about Italy’s landscape and culture: “If France is the country of reason, then Italy is the country of imagination. . . . Here is all you could wish for in a landscape—the oranges hanging so yellow between the lush greenery; big, grass-green lemons greeted us with their fragrance.—Everything was like a painting. . . . When visiting the magnificent galleries, the rich churches with their monuments and magnificence, I learned to understand the beauty of form—the spirit which reveals itself in form” (Diaries, 48).

HARRY CLARKE

Eels and eel-like fish serve as extensions for the Sea Witch’s hair. The magical potion drifts down to the little mermaid, whose grace is admired by some of the fish below.

30. with her arms wrapped around the beautiful marble statue. The little mermaid clings to the statue in much the way that the flowers wind their stems and leaves around the tree, blocking its light. Drawing on the ancient marriage trope of the elm and the vine, Andersen points to the possibility that the little mermaid’s feminine devotion to the prince may block light from the sun and thereby stand in the way of her salvation rather than promoting it.

31. There was so much she would have liked to know. The little mermaid is intent on broadening her horizons. What she sees on earth stimulates her desire for challenges. She wants, above all, to explore the world—by flying across oceans and climbing mountains—to discover what is beyond the realm of “home.” Her twin longing for both the prince and the world he inhabits create two competing narrative models, one based on the male bildungsroman, or novel of education, the other on the female marriage plot. As Rhoda Zuk puts it, “The heroine’s aspiration to progress and perfection is forwarded by the virtues appropriated from feudal romance . . . including imaginative sympathy, resourcefulness, courage, and self-discipline. Yet the tale is also predicated on the marriage quest” (Zuk, 166).

HARRY CLARKE

The little mermaid dances in a skirt forming an oval that contrasts with elongated leglike patterns behind her. The touch of red is reminiscent of Karen’s footwear in “The Red Shoes.”

32. We lack an immortal soul. Andersen was deeply invested in conveying Christian messages about immortal souls and eternal life, even as he and his characters clearly delight in worldly pleasures. Roger Sale finds the hierarchies set up in the tale nearly intolerable, for the prince, who is “a dense and careless man,” is positioned as morally and spiritually superior to the mermaid.