De vilde svaner

Andersen’s source for this tale was Matthias Winther’s “The Eleven Swans” (included at the end of the annotations to this tale),published in his Danish Folktales of 1823. It is easy to imagine why Andersen would have been drawn to a tale that included majestic birds that represented for him mys-tery,spirituality,and sublime beauty. Andersen must also have been drawn to the mute heroine of the tale, who, like the little mermaid, suffers in silence until her moment of glory and transfiguration. Raised as an only child and always seeking “brothers” and “sisters” in his friendships, Andersen saw in this story a fantasy of sibling solidarity that he could never realize in real life.

The Brothers Grimm had included versions of this tale type in their Children’s Stories and Household Tales published in 1812 and 1815. In “Twelve Brothers,” a girl accidentally turns her brothers into ravens; in “Seven Ravens,” a father curses his sons, transforming them into ravens; and in “Six Swans,” a wicked queen casts the spell that enchants her stepsons. All of these tales show how curses can be undone with heroic determination and heartfelt generosity. For the cultural critic Marina Warner, these stories were childhood favorites, for they tell a tale of female heroism: “I had no brothers, but I fantasized, at night, as I waited to go to sleep, that I had, perhaps even as many tall and handsome youths as the girl in the story, and that I would do something magnificent for them that would make them realize I was one of them, as it were, their equal in courage and determination and grace” (Warner, 392). “The Wild Swans,” like its many folkloric cousins, is the stuff of dreams, but its heroine accomplishes her task with unwavering resolve, and the bond between her and the brothers remains tender, strong, and indissoluble.

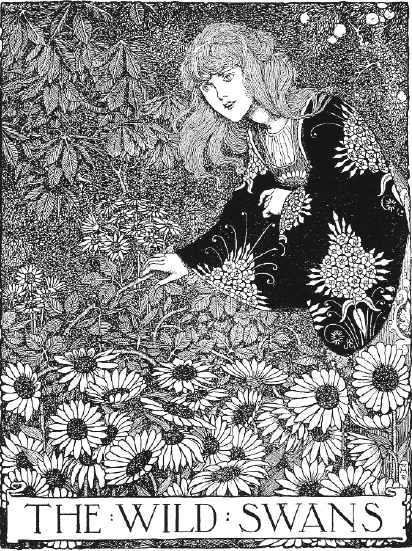

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Elisa picks nettles in a field covered with flowers. She herself wears a dress that, with its floral designs, reveals her alliance with nature.

Far, far away, where the swallows fly when it’s winter here,1 there lived a king who had eleven sons and one daughter named Elisa.2 The eleven brothers, princes all, went to school wearing stars on their chests and swords at their side. They did their writing on golden tablets with pencils of diamond, and they could recite their lessons just as well from memory as from a book. You could tell at once that they were princes. Their sister, Elisa, used to sit on a little stool made of mirror glass3 and look at a picture book that cost half the kingdom.4

Oh, those children were truly happy, but it was not to last forever.

The children’s father was king of all the land, and he married an evil queen who was not at all kind to the poor children.5 That was obvious from the very first day. During the festivities at the palace, the children played at entertaining guests.6 But instead of letting them have, as usual, all the cakes and baked apples that they wanted, the queen just gave them some sand in a teacup and told them to pretend that it was something special.

The next week the queen sent little Elisa out to the country to live with peasants. And it wasn’t long before she tricked the king into believing so many lies about the poor princes that his heart turned against them.

“Go out into the world and fend for yourselves,” the wicked queen told the boys. “Fly away like great big birds without voices.”7 But she could not harm the princes as deeply as she intended, for they turned into eleven beautiful white swans. Uttering strange cries, they flew out the castle windows, over the park and into the woods.

It was still quite early in the morning when they reached the farmer’s house, where their sister, Elisa, was sleeping. They hovered above the roof, craning their long necks and flapping their wings, but no one heard them or saw them. They had to keep flying, climbing up toward the clouds, far away into the wide world until they reached a vast, dark forest that stretched all the way down to the shores of the sea.

Inside the farmer’s house, poor little Elisa was playing with a green leaf, for she didn’t have any other toys. She poked a little hole in the leaf and looked at the sun through it. It was like looking at her brothers’ bright eyes. Whenever the warm sunshine touched her cheek, she was reminded of their kisses.

One day was just like the next. When the wind stirred the rosebushes outside the farmhouse, it would whisper: “Who could be more beautiful than you?”8 But the roses would shake their heads and say “Elisa is!” And when the old farmer’s wife sat by the doorway on Sunday, reading her hymnal, the wind would rustle the pages asking the book: “Who could be more devout than you?” “Elisa is,” the hymn book replied. And what the roses and the hymnal said was the plain truth.

When she turned fifteen, Elisa returned home. The queen saw how beautiful she had become and was filled with anger and resentment. She would have liked to turn her into a wild swan, along with her brothers, but she did not dare do it right away, because the king wanted to see his daughter.

Early the next morning, the queen went to the baths, which were built of marble and furnished with soft cushions and the loveliest tapestries. She took three toads, kissed them, and said to one of them: “Hop onto Elisa’s head when she gets into the bath so that she will grow to become as sluggish as you are.” And to the second she said: “Cling to her forehead so that she will become as ugly as you are, and her father won’t recognize her.” And to the third toad she whispered, “Settle on her heart and give her an evil soul so that she will suffer.” Then she lowered the three toads into the clear water, which promptly turned a greenish color. She called Elisa, undressed her, and made her get into the bath. Once Elisa was in the water, one of the toads climbed into her hair, another onto her forehead, and the third against her heart. Elisa did not seem to be aware of them at all, and, when she stood up, three red poppies were floating on the water.9 If the toads had not been poisonous and the witch had not kissed them, they would have turned into red roses, but they became flowers nonetheless, merely by touching Elisa’s head and heart. She was too innocent and devout for witchcraft to have any effect on her.

When the evil queen realized this, she rubbed Elisa all over with walnut juice until she turned dark brown, smeared her beautiful face with a vile ointment, and left her lovely hair in a tangled mess. You could not recognize the beautiful Elisa. When her father set eyes on her, he was horrified and insisted that she could not be his daughter.10 No one else would have known who she was except the watchdog and the swallows, but they were humble creatures and had no say in the matter. 11

Poor Elisa began to weep as she thought of her eleven brothers, who were all so far away. With a heavy heart, she stole out of the palace and spent the day wandering over fields and moors until she came to a vast forest. She had no idea where to turn, but she was full of sorrow and longed to be with her brothers, who had also been driven out into the wide world. She set her heart on finding them.

Not long after Elisa entered the forest, night fell. She had wandered far away from roads and paths. She said her prayers and lay down on the soft moss, leaning her head against the stump of a tree. It was quiet, and the air was sweet. Hundreds of fireflies glittered like some kind of green fire above the grass and moss.12 When she gently touched a branch with her hand, glittering insects darted all around her like shooting stars.

All night long she had dreams about her brothers. 13 They were children again, playing together, writing with their diamond pencils on their golden tablets and looking at her wonderful picture book that had cost half a kingdom. But they were no longer just scribbling circles and lines as they once had. No, they were writing about their bold deeds and about everything they had seen and done. What was once in the picture book had come alive.14 Birds were singing, and people stepped out of the pages of the book and talked with Elisa and her brothers. But the moment she turned a page, they leaped back into place so that the pictures wouldn’t get out of order.

When Elisa awoke, the sun was already high overhead.15 She couldn’t actually see it through the dense branches of the tall trees around her, but the sun’s rays played through the tangle of branches like a golden veil aflutter. There was a fresh, green scent in the air, and the birds flew so close that they nearly perched on her shoulder. She could hear the sound of water splashing—many large springs flowed into a pond with the most beautiful sandy bottom. Thick bushes had grown all around, but in one spot deer had made a large opening, one wide enough to allow Elisa to reach the water. The pond was so clear that, if the wind had not stirred the branches and shrubs all around, you would have thought that they were painted on its surface. Every leaf—whether in the sun or in the shade—was reflected perfectly on the waters.

When Elisa saw her face in the water, she was frightened, for it was so stained and ugly. But when she dipped her little hand into the water and rubbed her eyes and forehead, the pale skin shone through again. She took off her clothing and stepped into the cool waters. You could not have found a more beautiful royal child16 anywhere in the world.

After Elisa put her clothes back on and braided her long hair, she went over to the sparkling spring and drank from the hollow of her hand. Then she wandered deeper into the woods, not knowing where she was going. She thought about her brothers and about the good Lord who would surely not abandon her. He had made wild apples grow to feed those who were hungry, and he led her to a wild apple tree, its branches weighed down by fruit. Here she ate her midday meal and propped up the tree’s branches. Then she entered the deepest part of the forest. It was so quiet that she could hear the sound of her own footsteps and every little dry leaf crushed under her foot. There were no birds in sight, and not a single ray of sunshine was able to penetrate the thick, dense tree branches all around. The tall trees were growing so closely next to each other that, when you looked straight ahead, it seemed as if a solid fence was surrounding you. Elisa had never before known such loneliness. 17

The night was pitch black, and not a single firefly could be seen in the moss. Feeling sad, Elisa lay down to sleep. Suddenly the branches above her seemed to part, and the good Lord was looking down kindly upon her. Little angels peeked out from above his head and under his arms.

When Elisa woke up the next morning, she had no idea whether she had dreamed what had happened or whether it was real. She had taken no more than a few steps when she met an old woman carrying a basket of berries. 18 The old woman gave her a few, and Elisa asked whether she had ever seen eleven princes riding through the forest.

“No,” the old woman said, “but yesterday I saw eleven swans with golden crowns on their heads floating down the river not far from this spot.”

The old woman led Elisa some distance away to a steep slope. Down below, a stream wound its way, and trees on both banks stretched their long, leafy branches toward each other. Wherever their limbs couldn’t touch, they had pulled their roots loose from the earth and leaned out over the water until their branches met. 19

Elisa took leave of the old woman and followed the river down to where it flowed into the great open sea.

The vast, beautiful sea lay in front of the young girl, but there was not a sail in sight, and not a boat to be seen. How could she possibly continue her journey? She looked at the countless pebbles on the beach, all washed round and smooth by the water. Glass, iron, rocks, everything that had washed up had been worn down by the water, and yet the water was so much softer than her delicate hand. “It keeps on rolling and never tires, and it smoothes out whatever is hard. I want to be just as strong! Thanks for the lesson, dear waves that rise and fall. My heart tells me that someday you will carry me to my beloved brothers!”

Scattered among the seaweed washed up on shore, Elisa found eleven white swan feathers, and she gathered them up into a little bundle. There were still drops of water on them, but she could not tell whether they were drops of dew or tears. It was lonely out there by the sea, but she didn’t mind, because the sea was always changing20—in a matter of hours it could change more dramatically than a freshwater lake does in an entire year. When a big black cloud appeared in the sky, the sea appeared to be saying: “I can also look threatening.” Then the wind would blow, and white crests would rise on the waves. But if the clouds turned crimson and the winds died down, the sea looked just like a rose petal. Sometimes it looked green, then it would turn white, but no matter how calm it might appear, there was always some kind of gentle movement at the shore. The water rose and fell softly, like the chest of a sleeping child.

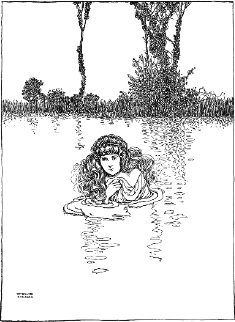

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Elisa scans the vast horizon in search of a sail, but she remains isolated on the surface of the waters.

Just as the sun was setting, Elisa caught sight of eleven swans with golden crowns on their heads21 flying toward land. Like a long, white ribbon, they glided in, one after another. Elisa climbed up the slope and hid behind a bush. The swans landed near her and flapped their magnificent white wings.

When the sun had disappeared into the water, the swans shed their feathers, and there stood eleven handsome princes—Elisa’s brothers. Although they had changed a great deal, she knew in her heart that she was not mistaken. She uttered a loud cry, and rushed into their arms, calling them each by name. They were overjoyed to see their little sister, who had grown so tall and lovely. They laughed and they cried, and soon they understood exactly how badly their stepmother had treated all of them.

“We brothers,” said the eldest, “fly like wild swans as long as the sun remains in the sky. When it sets, we return to our human form. And so at sunset we must always try to find firm ground, because if we were still flying up in the clouds, we would come plunging down into the deep. This is not where we live. Beyond the sea there is another land as fair as this one, but it is far away. You have to cross the vast ocean to reach it and there is not a single island along the way to spend the night, just one little rock jutting up midway across. There’s barely room for us to stand on it, even when we are right next to each other. If the sea is rough, the water sprays right on us. But still we thank God for that one spot where we can rest as humans during the night. Otherwise we would never be able to visit our own dear homeland. It takes two of the longest days of the year for us to complete the journey. We can visit the home of our ancestors only once a year, and we don’t dare stay longer than eleven days.

“When we fly over this forest we can see the palace where Father lives and where we were born. We can see the high tower of the church where Mother lies buried. And even the trees and bushes feel like family to us. Wild horses gallop across the moors as they did when we were young, and the charcoal burner sings the same old songs to which we used to dance as children. This is our homeland. It draws us close, and here, dear sister, we have found you again. We can stay for just two more days, and then we must fly across the sea to a land which is quite beautiful, but not our own. How shall we ever manage to take you with us? We have neither a ship nor a boat.”

“How will I be able to set you free?” their sister asked, and they talked for most of the night, sparing only a few hours for sleep.

The next morning Elisa awakened to the rustling of swans’ wings overhead. Her brothers had been transformed again, and they were flying in ever widening circles until finally they were out of sight. But one of them, the youngest, stayed behind. He rested his head in Elisa’s lap, and she stroked his white wings. They spent the entire day together. Toward evening the others returned, and when the sun set, they resumed their human shape.

“Tomorrow we must fly away from here,” one of the brothers said, “and we will not be able to return for a whole year. But we can’t leave you alone like this. Do you have the courage to come with us? My arm is strong enough to carry you through the forest, and surely the strength of our wings can be used to carry you across the sea.”

“Yes, take me with you!” Elisa said.

Together they spent all night braiding a net from the softest willow bark and the toughest rushes to be found, and they made it big and strong. Elisa lay down in it. When the sun rose and the brothers had been turned back into wild swans, they lifted the net with their bills and flew high up toward the clouds with their dear sister, who was still fast asleep.22 Since the sun’s rays were shining right down on her face, one of the swans flew overhead to provide shade with his broad wings.

They were still far from land when Elisa woke up. She thought she must be dreaming, because it was so strange to be high up in the air, flying over the sea. A bunch of tasty roots and a branch covered with delicious ripe berries were at her side. They had been gathered by the youngest of the brothers and placed there for her to eat. Elisa smiled at him with gratitude in her eyes, for she could tell that he was the one flying right above her and protecting her from the sun with his wings.

They were flying so high up that the first ship they caught sight of looked like a white seagull floating on the water. A large cloud rose up behind them, the size of a mountain. Elisa could see the gigantic shadows cast by herself and the eleven swans as they flew. It was the most magnificent sight she had ever seen. But as the sun rose higher and the clouds faded into the distance, the phantom shadows disappeared.

HARRY CLARKE

Lying in her net of willow bark and rushes, intertwined with decorative ribbons, Elisa flies up to the clouds and back down again with her brothers.

All day long the swans soared like arrows flying through the air. And yet, because they were carrying their sister, they were moving more slowly than usual. Evening was approaching, and a storm was brewing. With rising anxiety, Elisa noticed that the sun was beginning to set, and the solitary rock in the sea was still nowhere to be seen. It felt to her as if the swans were flapping their wings harder and harder. It was all her fault that they couldn’t fly faster. When the sun went down, they would turn into humans, plunge into the sea, and drown. She prayed to the dear Lord with all her might, but there was still no sign of the rock. Black clouds were gathering, and strong gusts of wind warned of a storm. The clouds formed one huge, menacing wave23 that came rushing toward them like a mass of molten lead. One lightning bolt after another flashed across the skies.

The sun was just reaching the rim of the sea. Elisa’s heart was beating like mad. Suddenly the swans took a quick downward plunge. Elisa was sure it was the end, but soon they were flying straight ahead again. The sun was halfway into the water when she caught sight of the little rock below them. It looked no larger than a seal poking its head out of the water. The sun was sinking so rapidly that it was now no bigger than a star. Just as Elisa’s foot touched solid ground, the sun went out like the last ember when a piece of paper finishes burning. She looked at her brothers, who were standing around her, arm in arm, and there was just enough space there for all twelve of them. The waves beat down on the rock and drenched all of them with sprays of water. The sky was lit up with fiery flashes, and thunderbolts kept crashing around them, one peal after another. Elisa and her brothers held hands and sang a hymn that gave them comfort and filled them with courage.

By dawn the air was clear and calm. As soon as the sun rose, the swans flew away with Elisa, leaving the rock behind them. The sea was still rough, and from the height at which they were soaring, the white crests of foam on the dark green waves looked like millions of swans floating on the waters.

As the sun rose higher, Elisa saw before them—almost hovering in the air—a mountain range. Its peaks were capped with glittering masses of ice, and from its midst rose a castle that seemed to be miles long, with one bold colonnade perched on another. Down below palm trees were swaying in the wind, and there were magnificent flowers as large as mill wheels24 below. She asked whether this was the land for which they were bound, but the swans shook their heads. What she had seen was Fata Morgana’s lovely castle25 in the air, a place that was always changing. They didn’t dare take anyone in there. When Elisa stared at it, the mountains, forest, and castle collapsed, and twenty splendid churches stood there, all exactly alike, with tall towers and arched windows. She thought she could hear the sound of an organ, but it was only the sea. As she drew closer to the churches, they turned into a fleet of ships sailing beneath her. She looked down again and saw nothing but sea mist drifting over the water. The scene kept changing before her eyes,26 and then at last she saw the actual country toward which she was headed. Lovely blue mountains with cedar forests, cities, and castles rose up before her. Long before sunset, she was sitting on a mountainside, in front of a cave carpeted with fine, green vines that looked like embroidered tapestries.

“Now we’ll see what you dream about tonight while you are here,” her youngest brother said, showing her where she was to sleep.

“If only I could dream about how to set you free,” she replied.

She was completely absorbed by this thought, and she was praying so ardently for God’s help that she was still speaking in her sleep. It seemed to her that she was flying to Fata Morgana’s castle in the air. The fairy who came out to meet her was dazzlingly beautiful, and she looked very much like the old woman who had given her the berries in the forest and who had told her about the swans with the golden crowns.

“You have the power to set your brothers free,” she said. “But do you have the courage and perseverance? The sea may well feel softer than your delicate hands, and yet it can still change the shape of hard stones. But it does not feel the pain that your fingers will feel. It doesn’t have a heart, and it doesn’t have to suffer the anguish and heartache that you will have to endure. Do you see these nettles in my hand? Many of them grow around the cave where you are sleeping. Listen carefully! You can only use the ones here and the ones that grow on churchyard graves. They will burn blisters on your skin, but you have to be sure to gather only those. Then crush the nettles with your feet, and you’ll get flax, which you must spin and weave into eleven shirts of mail with long sleeves. Throw those shirts over the eleven wild swans, and the spell will be broken. But remember! From the moment you start this task until it is finished, you may not speak.27 If you utter one word, it will pierce the hearts of your brothers like a deadly dagger. Their lives depend on your silence. Don’t forget what I have told you.”

At that instant, the fairy touched Elisa’s hand with a nettle. It burned her skin like fire and woke her up. It was broad daylight, and right near where she had been sleeping were nettles just like the ones she had seen in her dream. She fell to her knees to give thanks to God and left the cave to start her work.

With her lovely hands, Elisa picked the dreadful nettles that burned her hands and arms like fire, raising blisters on them. She did not mind as long as it meant that she would be able to free her beloved brothers. She crushed all the nettles with her bare feet and spun them into green flax.

When the brothers returned at sunset, they were alarmed to find that Elisa was unable to speak. They thought that their wicked stepmother had cast another spell, but when they looked at her hands, it dawned on them what she was doing for them. The youngest of the brothers burst into tears. And when his tears touched Elisa, the pain was gone,28 and the burning blisters vanished.

Elisa toiled all night long, for she did not want to rest until she had freed her beloved brothers. The next day, while the swans were away, she sat in solitude, but never had time flown by so quickly. One shirt of mail was already finished, and she set to work on the next one.

All at once, the sound of a hunting horn echoed through the mountains. She grew quite frightened. The sound came closer, and she could hear hounds baying. Terrified, she ran inside the cave, put the nettles she had gathered and woven into a small bundle, and sat down on it.

Suddenly a huge hound came bounding in from the thicket, followed by a second, and then a third. All three were barking loudly and running back and forth. Before long, a band of hunters had gathered in front of the cave. The handsomest among them was the king of the land, and he walked over to Elisa. Never before had he seen a girl so beautiful.29

“How did you get here, you lovely child?” he asked. Elisa could only shake her head, for she did not dare to say a word. Her brothers’ lives and their freedom were at stake. She hid her hands under her apron so that the king would not see what she had to endure.

“Come with me,” he said to her. “You should not stay here. If you’re as good as you are beautiful,30 I shall clothe you in silk and velvet, put a golden crown on your head, and you shall live in my grandest palace.” And the king lifted her up onto his horse. Elisa wept and began wringing her hands. The king said to her: “My only wish is to make you happy. One day you will thank me for this.” Off he rode through the mountains, with Elisa seated in front of him on his horse, with the hunters galloping behind them.

By the time the sun set, the magnificent royal city with all its churches and domes lay before them. The king took Elisa into his palace, where water was splashing in grand fountains in enormous marble halls, and where both walls and ceilings were decorated with paintings. But she had no eyes for any of these things. All she could do was cry and grieve. Without resisting, she let the women dress her in royal garments, weave strings of pearls into her hair, and pull fine gloves over her blistered fingers.

She was so dazzlingly beautiful in her finery that the whole court bowed even more deeply than before. And the king chose her as his bride, even though the archbishop was shaking his head31 and whispering that this lovely maid from the woods must be a sorceress who had bewitched the court and stolen the king’s heart.

The king refused to listen. He gave commands and music was played, sumptuous dishes were served, and lovely girls began dancing. Elisa was escorted through fragrant gardens into magnificent halls, but nothing could bring a smile to her lips or make her eyes sparkle. Sorrow had set its seal upon them as if that were her eternal destiny. At length the king opened the door to a little chamber adjoining her bedroom. It was covered with splendid green tapestries and looked exactly like the cave in which she had been living. On the floor lay the bundle of flax she had spun from the nettles, and from the ceiling hung the shirt of mail she had already woven. One of the hunters had decided to bring back these curiosities.

“Here you can dream yourself back to your old home,” the king told her. “This is the work that kept you occupied. Now, in the midst of all this splendor, it may amuse you to think back to that time.”

When Elisa discovered all the things that were so precious to her, a smile came to her lips, and the color came back into her cheeks. Overjoyed at the thought of her brothers’ salvation, she kissed the king’s hand. He pressed her to his heart and ordered that all the church bells ring in honor of the wedding celebration. The beautiful mute girl from the forest was crowned queen.

The archbishop continued muttering evil things into the king’s ear, but they could not reach his heart. The wedding took place,32 and the archbishop himself had to place the crown on her head. Out of malice, he pressed the tight circlet so low down on her forehead that it began to hurt. But an even heavier band gripped her heart. The sorrow she felt for her brothers kept her from feeling any pain in her body. Her lips were sealed, for a single word would spell the death of her brothers. In her eyes shone a deep love for the kind, handsome king who was doing everything in his power to make her happy. Every day she grew fonder of him, with all her heart. Oh, if only she dared confide in him and tell him of her torment. But she had to remain mute and finish her task in silence. At night she would steal away from the king’s side and retreat to her own little room, which was furnished like the cave. She finished knitting one shirt of mail after another, but just as she was about to begin the seventh shirt, she ran out of flax.

She knew that the nettles for the shirt were growing in the churchyard, and she had to pick them herself. How could she possibly get there?

“What is the pain in my fingers compared with the anguish I feel in my heart!” she thought. “I have to risk it, and I know God will not abandon me.”

With fear in her heart, as if she were about to commit some kind of evil deed, she tiptoed out into the garden by the light of the moon. She walked down avenues out into the deserted streets toward the churchyard. There she saw, seated in a circle on one of the largest tombstones, a group of hideous ghouls33—horrid witches. They were taking off their rags as if they were about to bathe, but then they buried their long, gaunt fingers in the new graves, snatched the bodies out of them, and began to eat their flesh. Elisa had to pass right by them, and they fixed their evil eyes on her, but she recited a prayer while she was picking the nettles that were stinging her and carried them back home to the palace.

One person had seen her—the archbishop, who had remained awake while everyone else was sleeping. He finally had proof for what he had long suspected. Something was not quite right about the queen. She must be a witch, and that was how she had managed to fool the king and all his subjects.

In the confessional, the archbishop told the king what he had seen and reported everything that he feared. As the harsh words escaped his lips, the carved images of the saints shook their heads34 as if to say: “That’s not true. Elisa is innocent!” The archbishop, however, had a different explanation. He claimed that they were bearing witness against her and that they were shaking their heads at her wickedness. Two big tears rolled down the king’s cheeks. He returned home with doubt in his heart. That night he did not sleep at all, but he pretended to be asleep when Elisa got up. Night after night she arose, and each time he followed her without making any noise and saw her disappear into the little room.

Every day the king’s countenance grew darker. Elisa noticed, but she had no idea what it meant. It made her worry and added to the pain she was already feeling about her brothers. Hot tears rolled down upon her royal robes of purple velvet. They glittered like diamonds, and everyone who saw this precious splendor wanted to be queen. Before long Elisa would be finished with her task. She had just one more shirt of mail to finish, but she ran out of flax again, and there was not a single nettle left. Once more, now for the last time, she would have to go to the churchyard and pick a few more handfuls. She was filled with dread at the thought of that lonely walk and of those ghastly witches, but her will was as firm as her faith in God.

Elisa went out, and both the king and archbishop followed her. They watched her disappear through the wrought-iron gates of the churchyard, and as soon as they entered, they saw the very same hideous demons sitting on a gravestone that Elisa had seen. The king turned away, for he imagined that Elisa—whose head had rested on his heart that very evening—was one of them.

“Let the people judge her,” he said. And the people did judge her and condemned her to burn at the stake.

Elisa was taken from the splendid royal halls to a dark, dank dungeon, where the wind whistled through the bars of the window. Instead of silk and velvet, she was given the bundle of nettles she had gathered as a place to rest her head. The harsh, stinging shirts of mail she had woven were her comforter and coverlet. Nothing they could have given her would have been more precious. She started her work again and prayed to God. Outdoors she could hear boys in the street mocking her with their songs. Not a soul came to comfort her with a kind word.

Toward evening a swan’s wing whooshed past the grating on Elisa’s window. It was the youngest of the brothers. He had found his sister, who sobbed aloud with joy, even though she knew that the coming night might be her last. Now her work was almost finished, and the brothers were there.

The archbishop arrived to pass the final hour with her, as he had promised the king. But Elisa shook her head, begging him with her eyes and with gestures to leave. Tonight she must finish her task or it would all be in vain—the pain, the tears, and the sleepless nights. The archbishop left, uttering cruel words about her, but poor Elisa knew that she was innocent and continued with her work.

Tiny mice ran across the floor,35 bringing nettles right to her feet and doing everything they could to help. A thrush perched near the bars of her window and sang all night long, as cheerfully as possible, so that she would not lose her courage.

In the early hours of the dawn, an hour before sunrise, the eleven brothers arrived at the palace gate, demanding an audience with the king. That was impossible, they were told. After all, it was still nighttime. The king was fast asleep, and no one dared wake him up. They pleaded and made threats until the guards turned out and even the king came out to find out what was wrong. Then suddenly the sun rose, and the eleven brothers vanished, but eleven swans could be seen flying over the palace.

Everyone in town was streaming through the gates, for they were all eager to watch the witch burn. A decrepit old horse was pulling the cart in which Elisa was seated. She was dressed in a smock made of coarse sackcloth. Her lovely, long hair was hanging loosely around her beautiful face. Her cheeks were deathly pale, and her lips were moving while her fingers were twisting the green flax. Even on the way to her death she would not stop the work she had begun. Ten shirts of mail lay at her feet, and she was working hard on the eleventh. The mob jeered at her.

“Look at the witch! See how she’s muttering under her breath. She doesn’t even have a prayer book in her hands. There she sits, with her revolting handiwork. Let’s take it away from her and tear it into a thousand pieces!”

The crowds surged toward her, trying to tear her work to bits. Suddenly eleven swans appeared, flapping their wings and making a circle around her. The mob drew back in terror.

“It’s a sign from heaven. She must be innocent,” many whispered, but no one dared to say it out loud.

The executioner grabbed her by the arm. In haste, she threw the eleven shirts over the swans, and instantly they turned into eleven handsome princes. The youngest had a swan’s wing in place of an arm, because his shirt of mail was missing a sleeve.36 Elisa had not quite managed to finish it. “Now I can speak,” she declared. “I am innocent.”

Everyone who had witnessed what had happened bowed down before her as if she were a saint. The strain, the anguish, and the pain were too much for her, and she sank lifeless into her brothers’ arms.

“She is indeed innocent,” the eldest brother proclaimed, and he told them everything that had happened. While he was speaking, the aroma of millions of roses began to spread,37 for every piece of wood piled on the fire had taken root and grown branches. An enormous hedge had spread out,38 dense with fragrant red roses. At the very top was a single blossom, gleaming white and shining like a star. The king broke it off and placed it on Elisa’s chest. She woke up, feeling peace and happiness in her heart.

All the church bells began to ring of their own accord, and birds appeared in great flocks. 39 A wedding procession headed back toward the palace40—one grander than any king had ever seen.

The Eleven Swans

by Matthias Winther

Once there lived a king with eleven sons and one daughter. When they were growing up, the queen died. The king spent so much time grieving over her that he believed he would never recover. But when the twelve children were grown up, he married again, but this wife was an evil witch. She could not stand the twelve children, and she sent the daughter out to work as a servant and transformed the eleven sons so that they were swans in the daytime and humans at night. They would fly far away, and the father was left all alone with the evil woman, sighing, and thinking often of the good wife who had died. When a year had passed, the sister returned home and asked about her eleven brothers, but she was not given an answer. She wondered where they could be, and she wept all the time, for she wanted to be with her brothers. She asked her father for money, took all her brothers’ clothes as well as their eleven silver spoons and went out into the wide world to find them.

She had walked for many days when she reached a great, dark forest. She wandered around for a long time until she reached a hut where an old woman was sitting and spinning. She asked whether she had seen the eleven boys, one older than the next, but the witch replied that she had only seen eleven beautiful swans floating on the river. The sister went to the river with hope in her heart and found a little straw hut. In it were eleven beds and eleven pots, with eleven wooden spoons in them. She took the wooden spoons out of the pots and put the eleven silver spoons in their place. And then she left. Towards evening, eleven snow-white swans came swimming up the river, and when they came to the hut, they turned into human beings. They were her brothers. When they went inside, they recognized their spoons, thought of their sister, and looked for her. The next day they turned again into beautiful swans and flew away over the tree-tops. But the sister had, in the meantime, made three nets, and when she finally found the eleven swans lying among the reeds, she threw nets over them and caught every single one of them. She asked how she could save them, but they could not tell her. She wept bitter tears and went with them through the woods to their hut. When thorns and bushes were in their way, she lifted the swans with care to prevent injury. She stayed with them at night, and the eleven swans put their heads on her lap and fell asleep. They turned human only in the middle of the night. During the day, the oldest brother dreamed that there was a way to save them. While remaining silent, their sister would have to go out in the morning and gather thistles in the field, then turn them into flax, spin and weave it, and sew eleven shirts from the cloth.

She went into the field to gather with her soft hands the thistles growing there. Then she turned them into flax and spun busily so that her brothers could return to their human form. One day the weather was so beautiful that she picked up the spinning wheel and took it outside into the woods. She was sitting under a tree and spinning, while the birds all around were singing to her. Her brothers were swans again and were floating far away on the river. As she sat there spinning, a king came riding past, and when he saw her, he thought that he had never seen a more beautiful woman. He took her home and married her. The old king had died just recently.

One day a message arrived for the king. He had to go to war. While he was away, the queen gave birth to two lovely children. The old queen took them away and ordered a servant to kill them. She put two motley pups in their place. Meanwhile the young queen continued spinning and weaving, thinking about her brothers and worrying about where they might be. When the king returned and heard that his wife had given birth to two pups, he became so angry that he ordered her to be murdered. By then she had finished all the shirts, except for one sleeve in the eleventh. She wept bitter tears once again, wishing that she had been able to finish her work. When the coach took her to the place of execution, eleven snow-white swans followed. They flew in circles around the queen and finally settled on the coach, fluttering their white wings. The queen threw one shirt after another on them, and, when the shirts landed on them, they turned into human beings. But the eleventh, who had the shirt with only one sleeve, kept one swan wing. The queen told the king everything that had happened. One of the servants was summoned. Out of pity, he had hidden the two princes instead of killing them. The second stepmother was put into a barrel with spikes and rolled down a hill to her death.

1. where the swallows fly when it’s winter here. Although the folktale being recast has its origins in Scandinavian countries and German-speaking countries, Andersen chose to set it in southern climes, in a domain where birds settle to escape the harsh winter climate of northern countries.

2. one daughter named Elisa. Elisa is a shortened form for Elisabeth, from the Hebrew Elisheba, which signifies that God is “satisfaction,” “perfection,” or “plenitude.” Unwavering in her mission to liberate her brothers from the spell that keeps them in animal form, Elisa becomes a figure who enacts the meaning of faith and devotion.

3. a little stool made of mirror glass. Fairy tales famously use gold to express beauty, but glass also appears frequently—in the form of slippers, coaches, coffins, axes, and mountains—symbolizing not only beauty but also clarity and rarity. To be sure, there is something absurd about a stool made of glass, but glass, like gold, is connected with delicate radiance.

4. look at a picture book that cost half the kingdom. Half the kingdom is a measure frequently used as the reward for princes and young men who rescue princesses. The value attached to pictures in this context reflects the degree to which the beauty of images is—especially for children—incalculable.

5. he married an evil queen who was not at all kind to the poor children. Like the stepmothers of Cinderella, Snow White, and Hansel and Gretel, this second wife withholds love and tries to banish the children from the safe enclosure of family life. The ghoulish creatures that appear later in the story embody her evil character, giving it physical force.

6. the children played at entertaining guests. “Company’s coming” was a common children’s game in Andersen’s time, and it is also played by the princess in “The Swineherd.”

7. “Fly away like great big birds without voices.” The curses and spells in fairy tales have been seen as bearing witness “to an early and perhaps continuous belief—or at least continuous reference to—a peculiarly female ability to control, direct or affect natural powers” (Bottigheimer, 43). The evil queen is initially described as a human, but her identity as a witch is quickly revealed, first by her ability to transform humans into birds, then by the term used to designate her in the bathing scene. The transformation of the boys into birds is accompanied by a loss of voice, anticipating the vow of silence Elisa will take. Margaret Atwood recalls the special attraction to her as a child of humans transformed into birds: “Now, in real life birds were birds. They cawed, hooted, quacked and chirped, and, if they were loons, made eerie sounds at night that caused the hair to stand up on your arms. But in fairy tales, birds were either messengers that led you deeper into the forest on some quest, or brought you news or help, or warned you, like the bird at the robbers’ house in ‘The Robber Bridegroom,’ or meted out vengeance, like the eye-pecking doves at the end of ‘Cinderella’; or else they were something you could be transformed into. These last were my kind of birds” (“Of Souls as Birds,” 25).

8. “Who could be more beautiful than you?” The rose and the hymnal, by combining beauty with piety, suggest that more is at stake than in the traditional folktale, where beauty alone is sufficient to mark the heroine’s magnetic quality. Note how Andersen adds a layer of Christian morality to a tale with pagan origins. The beauty of nature (as symbolized by the rose) and the beauty of the word (as symbolized by the hymnal) pale before Elisa, who becomes “the fairest of all,” but who remains unreadable because she cannot speak.

9. three red poppies were floating on the water. The red poppy has traditionally been a symbol of death, renewal, and resurrection. The flower has seeds that can remain dormant for years on end but will blossom when the soil is turned over. The fields of northern France and Flanders became the site of vast tracts of poppies after World War I, and their presence was commemorated in John McCrae’s famous verse: “In Flanders Fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses row on row.”

10. he was horrified and insisted that she could not be his daughter. The king’s repudiation of his daughter sets the stage for a second rejection that will take place when the king who marries Elisa listens to the archbishop’s denunciations of his wife. The atrocities at home are habitually repeated at the heroine’s second, new home in fairytale plots.

11. they were humble creatures and had no say in the matter. Andersen repeatedly placed his sympathies with migratory creatures like swallows, with whom he, as an energetic traveler, identified. In a letter to Jonas Collin, he described his nomadic habits: “Now I have a home for 25 rix-dollars a month, which I will probably fly away from when the first warm rays of the sun prickle me, the way they prickle the migratory birds” (Rossel 1996, 48). The watchdog may be a reference to Argos, the faithful dog who is the first to recognize Odysseus when he returns home disguised as an old beggar.

12. Hundreds of fireflies glittered like some kind of green fire above the grass and moss. Fireflies, also known as lightning bugs, and as glowworms (the term for the larvae and the wingless females), belong to the nocturnal beetles of the family Lampyridae, which have special chemicals in the abdomen that produce a flashing light. The males fly around in the evening during early summer. Andersen was fascinated with special light effects, the play of the sun’s rays, the sparkling of stars, and the Northern lights. Luminescence in general works a profound aesthetic and spiritual charm in Andersen’s works and, as holds true for “The Wild Swans,” provides inspiration and hope.

13. All night long she had dreams about her brothers. Elisa, unlike Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, and other characters from oral storytelling traditions, has a lively nocturnal dream life. In her dreams—which can be seen as a slow incubation period for developing the self—she reminisces about the past, ponders the future, and discovers the means to release her brothers from their enchanted state.

14. What was once in the picture book had come alive. The notion of a book whose characters can step out of the pages is a literary conceit, with origins in the Romantic period that flourished when Andersen was a boy. Related to the notion that portraits and statues can come to life, the concept suggests a breaking of the boundaries between art and life. In many children’s books, for example Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story, characters can enter into the story that unfolds while they are reading. Andersen may have been influenced by Heinrich von Ofterdingen (1799), a novel by the German Romantic Novalis, that charted the travels of a young man on his way to becoming a poet. On his journey, Heinrich encounters a hermit who possesses an exotic volume written in a foreign language. As he leafs through the pages, he realizes that the figures in the book represent him and members of his family, all dressed in costumes from another time and place.

15. the sun was already high overhead. Idyllic nature scenes abound in Andersen’s work, but the description of Elisa at the pond is almost unsurpassed in its beauty. The visual, aural, and olfactory elements combine to produce a utopian scene of arresting natural splendor, as the pure surface of the pond reflects and reproduces all that surrounds it.

16. a more beautiful royal child. The bathing scene presents a pagan baptism in which Elisa purges herself of her stepmother’s evil influence. If the earlier immersion in water (at home) had a transformative effect, this second cleansing reveals, once again, Elisa’s inherent nobility.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Elisa bathes in a pond in order to remove the stains left by the walnut oil and “vile ointment” applied by her stepmother.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

An old woman carrying a basket of berries emerges from the forest to help Elisa in her quest to disenchant her brothers. By contrast to the stepmother, she will offer guidance and advice.

17. Elisa had never before known such loneliness. After the idyllic beauty of the woodland scene comes a moment in which Elisa feels the deepest emotional despair of her entire ordeal. For the ugly duckling and other figures like Elisa, the existential crisis marks what J.R.R. Tolkien has referred to as the eucatastrophe, the dark desolation that signals a turning point that will lead to redemption.

18. an old woman carrying a basket of berries. Like the various old women in “The Snow Queen,” the woman with the basket of berries provides physical nourishment and spiritual guidance to the solitary heroine. Although she possesses no magical powers, she serves as a counterweight to the stepmother and her evil machinations, suggesting that benevolent forces will emerge in the course of the heroine’s peregrinations.

19. leaned out over the water until their branches met. The force of desire operates powerfully, even in nonsentient beings. The description of the trees transcending their rooted nature and reaching out to each other across the waters prefigures the strength of Elisa’s desire to reunite with her brothers. The kind of contact pictured here—reaching across obstacles to meet and embrace—mirrors the poetic effect of the kiss in Andersen’s works.

20. the sea was always changing. The notion of mutability is introduced in the descriptions of the changing landscape. The narrative begins with the transformation of the boys into swans and repeatedly takes up the theme of metamorphosis. The toads in Elisa’s bath, for example, are turned into poppies. Here, the landscape participates too, albeit in more subtle ways, in the process of transformation.

21. eleven swans with golden crowns on their heads. The swans are presented as a wondrous sight. As in “The Ugly Duckling,” their golden crowns mark them as royal beings, and their movements create the impression of an aesthetic ornament that fills the sky with beauty. Swans, as Jackie Wullschlager points out, were cherished birds in Andersen’s personal mythology. They were closest to his “romantic selfimage as wild, pure, lofty and loyal.” They are also, as she points out, monogamous creatures who take care of their young as a pair. They appear to soar with great power in the air even as they are “elegantly resigned” on water and “uncomfortable and graceless” on land (Wullschlager, 189). And, as Boria Sax points out, their families, “at least viewed from a distance, seem close to the domestic idylls of the human imagination” (Sax, 63).

22. who was still fast asleep. Even as Elisa becomes savior to her brothers, she also becomes something like a child to the swan brothers. Placed in netting that resembles a cradle, she is sheltered from the sun by one of their protective wings. She is even provided with nourishment in her aerial bed.

23. The clouds formed one huge, menacing wave. During the travels of the brothers and their sister, “up,” “above,” and “down below” become nearly interchangeable. The clouds above take on the characteristics of the ocean, and the world becomes one vast tract without any kind of division between air and sea. Swans are, of course, at home on land, in the air, and at sea.

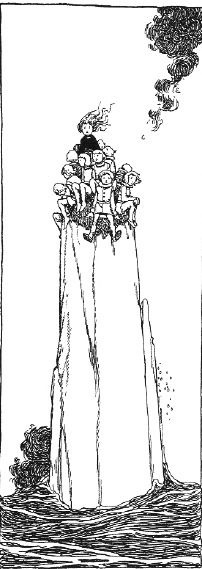

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Elisa and her brothers huddle together on a rock that has just enough room for them to stand. Black clouds, thunderbolts, and waves threaten them all around.

24. as large as mill wheels. In “The Tinderbox,” Andersen used mill wheels to describe the size of the dog’s eyes.

25. Fata Morgana’s lovely castle. Fata Morgana, also known by the name of Morgan le Fay, is an enchantress with the ability to transform her appearance. Trained by Merlin the Magician, she is described by one source as King Arthur’s shape shifting half-sister. Her name is used to describe a special type of mirage, formed by alternating warm and cold layers of air near the ground or near the water, that appears in the form of a castle half in the air and half in the sea. Fata Morgana was said to live in a castle under the sea, and the enchantress had the capacity to cause the castle to appear reflected in the air. Sailors would be lured to their deaths when they mistook her magnificent castle for a safe harbor. The term is used colloquially to denote a mirage or optical illusion.

26. The scene kept changing before her eyes. Mutability in the landscape creates a sense of dangerous instability. Elisa has little control over her constantly changing environment when she flies with her brothers.

27. you may not speak. Like the little mermaid, Elisa combines virtue with silence, epitomizing heroism as she sacrifices her own well-being for others. The yoking of virtue with silence appears frequently in earlier literature—for instance, Shakespeare’s Cordelia in King Lear and Constance in Chaucer’s “Man of Law’s Tale.” Marina Warner locates the origins of this fairy tale in a time when “women’s capacity for love and action tragically exceeded the permitted boundaries of their lives” (Warner, 392–93). The silence in this particular tale creates a sense of powerlessness even as the heroine is developing the capacity to transform her brothers. Ruth B. Bottigheimer points out that “a historical understanding of fairy tales leads to the conclusion that insistent privation or imminent deprivation can be and have been recast into a narrative in which silence and being condemned to silence stand for the domestic, political and social experience of the poor” (Bottigheimer, 73).

28. the pain was gone. The power of tears to heal is evident in stories like “Rapunzel,” in which the heroine’s tears have the capacity to bring sight back to the prince’s eyes. In “The Snow Queen,” Gerda’s tears break the wintry spell cast on Kai by the glass splinter in his heart.

29. Never before had he seen a girl so beautiful. Max Lüthi has pointed out that the actual form beauty takes in fairy tales is rarely made explicit: “The beauty is abstract. The listener must fall back on his own imagination.” He notes further that this kind of abstract beauty does not have an erotic quality: “Beauty spellbinds and attracts, and with magic power. But there is no talk of sensual vibration, either with respect to the beautiful girl herself or with respect to those affected by her” (Lüthi, 4–5). Andersen’s fairy tales, in contrast to his novels and plays, construct beautiful scenes and images that yield aesthetic rather than sensual pleasure.

30. If you’re as good as you are beautiful. In On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry notes that virtue and beauty are powerfully linked: “beautiful things give rise to the notion of distribution, to a life-saving reciprocity, to fairness not just in the sense of loveliness of aspect but in the sense of ‘a symmetry of everyone’s relation to one another’ ” (Scarry 1999, 95). Elisa is fair in both senses of the term. She rights the wrongs of the stepmother and becomes an agent of justice, restoring her brothers to their human form and returning them to their natural home.

31. even though the archbishop was shaking his head. In most other versions of the tale, it is a mother-in-law or other evil female figure who spreads vicious rumors about the heroine, switching her newborn child with whelps or monsters and branding her a sorceress. The association of evil with an ecclesiastical figure reflects skepticism about nineteenth-century religious orthodoxies. More importantly, it is also consonant with a deeply critical attitude toward the clergy in folktales. Parsons and priests are frequently represented as freeloaders and cheats who deserve to have the tables turned on them.

32. The wedding took place. This first wedding is a ceremony that may bring Elisa and the king together in official terms, but they remain divided because of Elisa’s secret.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Elisa steals out of the castle and makes her way to the churchyard in order to find the nettles she needs to finish the shirts.

33. a group of hideous ghouls. The flesh-eating witches in the churchyard are a reminder that, from the 1400s up until 1693, the Danes engaged in witch hunts (coinciding with those in Salem and elsewhere) that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of old women.

34. the carved images of the saints shook their heads. In “The Red Shoes,” the paintings on the walls appear to fix their eyes on Karen’s footwear. Certain sins are so brazen that even images of the dead are stirred back to life in protest. But Elisa herself, a miracle of beauty and piety, can also work wonders.

35. Tiny mice ran across the floor. Elisa, like many orphaned children in fairy tales, finds in nature a source of aid and support. The mice and the birds, like the birds in “Cinderella,” make sure that she can complete the tasks assigned to her. Protagonists of fairy tales often become children of nature. Cut off from human help, they find in animals the help they need.

36. because his shirt of mail was missing a sleeve. The tiny flaw that accompanies the great accomplishment provides a moment of imperfection in a genre that famously prefers perfection and utopian closure to compromise and negotiation. Falling just short of a deadline can lead to resolution, as in this tale, but more frequently it ushers in a second catastrophe.

37. the aroma of millions of roses began to spread. Bengt Holbek points out how innocent goodness triumphs over evil in this story. He emphasizes the difference between the virtues set forth in folktales and those celebrated in Andersen’s work: “In Andersen’s universe, the qualities of good and evil have become absolute. . . . We observe a number of what may be called social virtues like helpfulness, generosity, steadfastness in danger, faithfulness, honesty and so on” (Holbek, 157).

38. An enormous hedge had spread out. The dense hedge of roses is, of course, well known from “Sleeping Beauty.” For Andersen, the rose bears an added redemptive layer. The white blossom signals innocence and salvation, and the red, passion and love.

39. birds appeared in great flocks. Birds, which can soar high into the heavens while roses remain rooted on earth, add a further dimension of spirituality to the tale. And these creatures are, of course, kindred to the boys in their avian form.

40. A wedding procession headed back toward the palace. This second wedding will presumably be marked by more trust than the first, for the king’s willingness to listen to the archbishop and to let his wife perish by fire did not signal great confidence in Elisa.