Tommelise

“Thumbelina” was the first story in the second installment of Andersen’s Eventyr, published in December 1835, just in time for Christmas. Its date coincided with his first real triumph as a writer: publication of the novel The Improvisatore, soon reprinted and translated into German. The first volume of fairy tales had met with mixed reviews; at least one reviewer advised Andersen to stop writing them altogether. In his introduction to the third volume, Andersen conceded that such reviews “weakened the desire” to write but that he had persevered. Reviving his memory of tales heard in spinning rooms and at harvest time, he brightened up “the faded colors of the images” and used them as the point of departure for imaginative creations of his own.

“Thumbelina,” Andersen’s tale of a runaway bride, has been variously interpreted as a tale teaching that “people are happy when with their own kind” (Opie, 288), as an allegory about “arranged marriages that were not uncommon in the bourgeoisie of that time” (Ingwersen 1993, 168), and as a “straightforward fable about being true to your heart” that also upholds “the traditional notion that fame and fortune aren’t worth a hill of beans compared to the love of a good old-fashioned prince” (Holden, C19). Thumbelina can also be seen as a female counterpart to the heroic Tom Thumb. Both are diminutive creatures who suffer through all manner of ordeals and survive against all odds. Thumbelina earns her good fortune and becomes a queen after an act of compassion (reviving the swallow), and Tom Thumb uses his cunning to defeat the ogre and return home to live like a king with his parents and siblings. According to Hindu belief, a thumb-sized being known as the innermost self or soul dwells in the heart of all humans and animals. Most likely the concept migrated into European folklore, surfacing in the form of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, both of whom can be seen as figures seeking transfiguration and redemption. Note that Thumbelina is renamed Maya.

“Tommelise” is the Danish title of the tale. The first English translations of the story used the names “Little Ellie,” “Little Totty,” and “Little Maja.” The name Thumbelina was first used by H. W. Dulcken, whose translations of Andersen’s tales appeared in England in 1864 and 1866, and it is now the name used in most translations and in all films based on the tale. There have been at least five cinematic adaptations, beginning with Lotte Reiniger’s in 1954 and including Barry Mahon’s (1970), Shelley Duvall’s (1984), Don Bluth and Gary Goldman’s (1994), and Glenn Chaika’s (2002). Frank Loesser’s lyrics for the 1952 film Hans Christian Andersen contain the song about Thumbelina that is still well known today: “Though you’re no bigger than my thumb . . .”

Once upon a time there lived a woman who was longing for a tiny little child, but she had no idea where to find one. Finally she decided to call on an old witch,1 and she said her: “My heart is set on having a little child. Can’t you tell me how I can get one?”

“That’s easily done,” the witch said. “Here’s a grain of barley,2 but it isn’t the kind grown by farmers in their fields or the sort used to feed chickens. Put it in a flower pot, and you shall see what you shall see.”

“Thank you so very much,” the woman said, and she gave the witch twelve pennies and planted the seed as soon as she arrived back home. The seed quickly grew into a big, beautiful flower that looked just like a tulip, but its petals were folded tightly, as though it were still a bud.

“What a lovely flower!” the woman declared, and she planted a kiss on its beautiful red and yellow petals. With the kiss, the flower went pop! and opened up. It was a tulip, sure enough, but in the middle of it, on a little green cushion, sat a tiny girl. She was delicate and fair, but she was no taller than a thumb,3 and for that reason she came to be known by the name of Thumbelina.

A brightly polished walnut shell served as Thumbelina’s cradle. Her mattress was made from the blue petals of violets, and a rose petal became her coverlet. That was how she slept at night. In the daytime she spent her time playing on a table where the woman had placed a dish, filled with a wreath of flowers. The stems of the flowers reached into the water, and a big tulip petal floated on the surface. Thumbelina sat in it and sailed clear across the dish, using a pair of white horsehairs for oars. It was a charming sight! She could sing too, and no one had ever heard a voice as soft and sweet as hers.4

One night as she lay in her pretty bed, a hideous toad hopped in through the window5—one of the panes was broken. The repulsive toad, big and slimy, jumped right onto the table where Thumbelina was lying fast asleep under the red rose petal.

“She’ll make a perfect wife for my son!” the toad exclaimed, and she grabbed the walnut shell in which Thumbelina was sleeping and hopped off with it, out the window and into the garden.

A wide stream wound its way through the garden, and its banks were muddy and swamplike. That’s where the toad lived with her son. Ugh! He was just like his mother, ugly and horrid. “Ko-ax, ko-ax, brekke-ke-kex!” was all he could say6 when he saw the lovely little girl in the walnut shell.

“Don’t raise your voice or you will wake her up,” the old toad said. “She might get away from us yet, because she’s as light as swan’s down. We had better put her on one of those big water-lily pads out in the stream. She’s so tiny and dainty that it will seem just like an island to her. That way she can’t escape, and we’ll have a chance to fix up the parlor down in the mud for the two of you.”

There were many water lilies growing in the stream, and their big green pads looked just as if they were floating on the surface. The pad farthest away was also the largest, and the old toad swam out to it and there she left the walnut shell, with Thumbelina fast asleep in it.

The poor little thing woke up early the next morning, and when she saw where she was she began to weep bitter tears, for there was nothing but water on all sides of the big green lily pad, and she had no way to reach the shore.

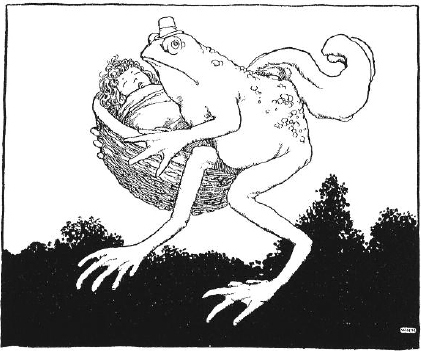

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Thumbelina sleeps peacefully in her walnut-shell cradle, while a toad hops off with her, hoping that she can turn the girl into her daughter-in-law.

The old toad was sitting in the mud, decorating the parlor with reeds and yellow water lilies, for she wanted it to look elegant for her new daughter-in-law. She and her ugly son swam out to Thumbelina’s lily pad to fetch her pretty little bed, which they were hoping to set up in the bridal chamber before she arrived there herself. The old toad made a deep curtsy in the water before Thumbelina and said: “Meet my son. He is going to be your husband, and the two of you will have a delightful home down in the mud.”

“Ko-ax, ko-ax, brekke-ke-kex!” was all her son could say.

Mother and son took the comfortable little bed and swam away with it. Thumbelina was left all alone on the green lily pad, weeping, for she did not want to live with the horrid toad or marry her revolting son. The little fish swimming in the water beneath her must have seen the toad and heard her words. That’s why they poked their heads out of the water to take a look at the little girl. As soon as they set eyes on her, they felt very upset that anyone so lovely would have to go live with that vile toad. No! That was never going to happen! The fish gathered down below around the green stem holding up the lily pad. They gnawed the stalk in half with their teeth, and the lily pad began to float downstream,7 taking Thumbelina far away, to a place where the toad could never reach her.

Thumbelina sailed past so many places, and little birds perched in the bushes watched her and chanted, “What a pretty little girl!” The lily pad carrying her drifted farther and farther away, and soon Thumbelina was traveling abroad.8

A lovely little white butterfly9 kept circling around her and finally landed on the lily pad because he had grown fond of Thumbelina. She was so happy that the toad would not be able to find her. Everywhere she sailed it was beautiful: the sun was shining on the water and turning it into the loveliest golden color. Thumbelina undid her sash, tied one end of it to the butterfly, and fastened the other to the lily pad. The lily pad began to move much faster, and so did Thumbelina, for she was, of course, standing on it.

Just then a big beetle flew by and caught sight of Thumbelina. He grabbed her slender waist with his claws and flew up into a tree with her. The lily pad kept floating downstream, and the butterfly went with it, for he was still tied to the lily pad and could not get loose.

Goodness! How frightened little Thumbelina was when the beetle flew up into the tree with her. But she was much sadder when she thought about the beautiful white butterfly that she had tied to the lily pad. If he couldn’t free himself, he would end up starving to death. But the beetle wasn’t one to worry about that. He set Thumbelina down on the largest green leaf of the tree, fed her honey from the flowers, and told her how pretty she was, even if she didn’t look at all like a beetle.10 After a while, all the other beetles living in the tree came to pay a visit. They stared at Thumbelina, and all the lady-beetles shrugged their feelers and said: “Why she has only two legs—how pitiful!”

“She has no antennae!” another one shrieked. “She’s pinched in at the waist—ugh!” the lady-beetles said. “Why, she looks just like a human being. How revolting!”

Yet Thumbelina was as pretty as ever. The beetle who had kidnapped her would have agreed, but all the others kept describing her as hideous. In the end the beetle went along with them and would have nothing to do with her any longer. She could now go where she pleased. The beetles brought her down from the tree and left her on a daisy, where she sat and wept because the beetles found her so ugly and would have nothing to do with her. In truth, she was the loveliest little creature you could imagine, as delicate and radiant as the most beautiful rose petal.

ELEANOR VERE BOYLE

Thumbelina floats on top of the water on her lily pad, which is pulled by the butterfly. The fish below seem unaware of her presence.

All summer long poor Thumbelina lived alone in the deep woods. She wove a bed for herself from blades of grass and hung it under a large burdock leaf to keep the rain away. She lived on honey from the flowers, and, every morning, she drank the dew found on the leaves. Summer and fall passed in that way, but then winter arrived, the long, cold winter. All the birds that had been singing so sweetly for her flew away, and the trees and flowers began to wither. The big burdock leaf under which she had been living curled up and soon there was nothing left of it but a dead yellow stalk. She was terribly cold,11 for she was slender and frail, and the clothes she had were threadbare. Poor Thumbelina, she was sure to freeze to death! Snow began falling, and whenever a snowflake fell on her, it felt just the way that an entire shovel load would feel to us. We are, after all, quite tall, and she was only as high as a thumb. Thumbelina wrapped herself in a withered leaf, but it didn’t keep her warm at all, and she began to shiver with cold.

At the edge of the woods was a vast field of grain, but the grain had long since been harvested, and there was nothing on the frozen ground but dry, bare stubble. For Thumbelina, it was like being lost in an immense forest, and, oh, how she was shivering with cold! She reached the door of a field mouse, right where there was a little hole amid the stubble. That’s where the mouse lived, snug and cozy, with a whole storeroom of grain and a lovely kitchen and pantry. Poor Thumbelina stood at the door, just like any other beggar child, and asked for a little bit of barley corn, because she had eaten nothing for the past two days.

“You poor little thing!” the field mouse said, for she was at heart a kind old field mouse. “Come into my warm parlor and join me for dinner.”

MABEL LUCIE ATTWELL

Thumbelina, shivering with cold, emerges from a vast forest to discover the home of the field mouse, who invites her to stay in her cozy abode.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Thumbelina is seated on a dry leaf, shivering from the cold, when she is greeted by the field mouse.

The field mouse took a fancy to Thumbelina and said to her: “You are welcome to stay here with me for the winter, but you must keep my house nice and clean12 and tell me stories, because I’m quite fond of them.” Thumbelina did exactly what the old field mouse asked and settled in comfortably.

“We’ll be having a visitor before long,” the field mouse said. “My neighbor usually comes to see me once a week. He is even better off than I am, and his rooms are much larger. He has such a lovely black velvet fur coat.13 If you could win him as a husband, you would be set for life. But he can’t see. You’ll have to tell him the most enchanting stories you know.”14

Thumbelina was not thrilled by that idea. She did not even consider the suggestion of marrying the neighbor, for he was a mole.15 The mole came to call, wearing his black velvet coat. All the field mouse could talk about was how wealthy and learned he was and how his lodgings were twenty times the size of hers. He had erudition as well, but he did not care at all for the sun and for flowers. He had nothing good to say about them because he had never set eyes on them. Thumbelina had to sing to him, and she sang both: “Fly, Beetle, Fly, Fly Away Home” and “The Monk Walks through the Meadows.” The mole fell in love with Thumbelina when he heard her beautiful voice, but he said nothing, for he was a most discreet fellow.

The mole had just finished digging a long underground passageway from his house to theirs, and the field mouse and Thumbelina were invited to use it whenever they wanted. He told them not to be alarmed by the dead bird lying on the path. The bird still had its feathers and beak, and it must have died not long ago, just about the time when winter was settling in. Now it was buried in the very place where the mole had dug out the tunnel.

The mole picked up a piece of decaying wood, which, in the darkness, glowed like fire and worked as a torch. He walked ahead of them, lighting the way through the long dark tunnel. When they came to where the dead bird was lying, the mole shoved his broad nose against the ceiling and made a large hole through which daylight streamed. In the middle of the floor you could see the dead swallow,16 his beautiful wings pressed to his sides and his head and legs tucked under his feathers. The poor bird must have died from the cold. Thumbelina felt so very sorry for him. She loved all of the small birds because they had sung and chirped so beautifully for her all summer long. The mole gave the bird a kick with his stubby legs and declared: “That’s the end of his chirping. Nothing could be worse than coming into the world as a little bird! Thank goodness none of my children will be birds. All they do is chirp, and then, when winter comes along, they end up starving to death.”

“Yes, you’re so right, sensible man that you are,” the field mouse agreed. “What good does all that chirping do for birds in the wintertime? They just end up starving and freezing to death. But I suppose people imagine that to be very noble.”

Thumbelina did not say a word, but when the others had turned their backs on the bird, she kneeled down, smoothed the feathers that were covering the bird’s head, and kissed his closed eyes. “Maybe it was he who sang so sweetly to me in the summertime,” she thought to herself. “What great pleasure you brought me, you dear, beautiful bird.”

The mole closed up the hole that let in daylight and escorted the ladies back home. That night Thumbelina did not sleep a wink. She got up and wove a beautiful coverlet out of hay, took it over to the dead bird, and spread it over him, tucking him in. She placed some soft cotton she had found in the field mouse’s parlor around the bird to keep him warm in the cold ground.

“Farewell, you beautiful little bird,” she said. “Farewell and thank you for your lovely summer song, when the trees were still green and the sun shone so warmly on us all.” Then she put her head on the bird’s breast, but felt quite frightened because it seemed as if something was making a pounding noise. It turned out to be the bird’s heart. He was not dead—he was only numb with cold, and now that he had been warmed up, he was returning to life.

In the autumn the swallows fly off to warmer climates, but if they linger, they can become so cold that they drop down as if dead. They end up lying wherever they happen to fall, and when the cold snow comes, it covers them up.

Thumbelina was so frightened that she began to tremble all over. The bird was so huge, just enormous compared to her own height of merely a thumb. But she gathered her courage, tucked the cotton closer around the poor bird, brought over the mint leaf that covered her own bed, and spread it over the bird’s head.

The following night she tiptoed back to see the bird. He was alive now, but so weak that he could barely keep his eyes open to take a look at Thumbelina, who was standing by his side with a piece of glowing wood, all the light that she had.

“Thank you, my pretty little child,” the ailing swallow said. “I feel so nice and warm again. Soon I’ll be strong enough to fly back into the warm sunshine.”

“Oh,” she replied. “It’s still cold outside—there’s snow and ice on the ground. Just stay here in your nice warm bed, and I’ll take good care of you.”17

Thumbelina found a flower petal and brought the swallow some water. He drank it and told her how he had torn his wing on a thorn bush and couldn’t keep up with the other swallows when they left to fly far away to the distant warm countries. He had finally landed on the ground. That was all he could remember, and he had no idea how he had ended up where he was.

The swallow stayed underground all winter long, and Thumbelina was kind to him and grew quite fond of him. She did not say a word to the mole or to the field mouse, for she knew that they would not care for the unfortunate swallow.

When spring arrived and the sun began to warm the earth, the swallow said farewell to Thumbelina, who opened up the hole that the mole had made overhead. The sunshine flooded in with splendor, and the swallow asked if Thumbelina wished to accompany him. She could climb on his back, and they would fly away into the green forest. But Thumbelina knew that the old field mouse would feel very sad if she left.

“No, I can’t leave,” Thumbelina said.

“Farewell, farewell, my pretty, kind child,” the swallow said as he flew out into the sunlight. Thumbelina gazed at the swallow as he departed, and tears filled her eyes, because she was so fond of him.

“Tweet, tweet,” the bird sang as he flew away into the green forest.

Thumbelina felt very sad. She wasn’t allowed to go out into the warm sunshine. And the grain sown in the ground above the field mouse’s house had grown so tall that, to a poor girl who was no bigger than a thumb, it was like a vast, dense forest.

“You must begin work this summer on your trousseau,” the field mouse told Thumbelina, because her neighbor, the loathsome mole in the black velvet coat, had already proposed to her. “You’ll need both woolens and linens. And you must have cushions and bedding once you become the mole’s wife.”

Thumbelina had to turn the spindle, and the field mouse hired four spiders to spin and weave, day and night. The mole came to call every evening, and he loved to talk about how summer would soon be over and the sun would no longer be so hot, scorching the earth and making it as hard as a rock. Yes, as soon as the summer was over, he would be marrying Thumbelina. But Thumbelina was not at all happy about it, because she did not like the dreary mole one little bit. Every morning at sunrise and every evening at sunset, she would steal out the door. When the breeze parted the ears of grain, she was able to catch glimpses of the blue sky. She would dream about how bright and beautiful it was outside, and more than anything else she wanted to see her dear swallow again. But he did not return, and he must have been flying far away into the beautiful green woods.

By the time autumn came, Thumbelina’s entire trousseau was ready.

“Four weeks until the wedding!” the field mouse told her. Thumbelina began to weep and declared that she had no wish to marry the dreary mole.

“Fiddlesticks,” said the field mouse. “Don’t be stubborn, or I’ll bite you with my white teeth. Why, you’re getting a superb husband. Even the queen doesn’t have a black velvet coat as fine as his. Both his kitchen and cellar are well stocked. You ought to be grateful for a fellow like that.”

The wedding day arrived. The mole had already come and was planning to take Thumbelina home with him. She would have to live deep underground and would never go out into the warm sunshine again, because he disliked it so much. The poor child felt miserable, because she had to bid farewell to the sun. At the home of the field mouse, she had at least had the chance to see it through the doorway.

“Farewell, bright sun!” she said, stretching her arms toward it as she took a few steps out of the field mouse’s house. By now, the grain had been harvested, and all that remained on the fields was dry stubble. “Farewell, farewell!” she said as she flung her tiny arms around a red flower that was still in bloom. “If you happen to see my dear swallow, please give him my love.”

“Tweet, tweet! Tweet, tweet!” she suddenly heard overhead. She looked up and there was the little swallow, flying overhead. He was overjoyed to see Thumbelina, who told him how much she hated the idea of marrying the mole and living deep under the ground where the sun never shines. She had trouble holding back her tears.

“The cold winter is on its way,” the swallow said to her. “I’m going to fly far away to the warm countries. Why don’t you come along? You can sit on my back. Just tie your sash around me,18 and we’ll fly far away from the hideous mole and his dark house—over the mountains to the warm countries where the sun shines so much more brightly than it does here and where it’s always summer, with beautiful flowers. Fly away with me, dear little Thumbelina. You saved my life when I was frozen in that dark underground cellar.”

“Why, yes, I’ll come with you!” Thumbelina exclaimed, and she climbed onto the bird’s back, put her feet on his outstretched wings, and tied her sash to one of the broader feathers. The swallow soared through the air, high up above forests and lakes over to the tall mountains that are always capped with snow. At first, Thumbelina shivered in the chill air, but then she crept under the bird’s warm feathers and poked her little head out to gaze at all the wondrous sights below her.19

At last they reached the warm countries. The sun was shining more brightly there than it ever does here, and the sky seemed twice as high. Along the ditches and hedgerows grew marvelous green and blue grapes. Lemons and oranges were hanging from trees in the forest, and the air was fragrant with myrtle and mint. The most adorable children were running on the road here and there, chasing after brightly colored butterflies. The swallow flew even farther away, and everything became even more beautiful. Beneath magnificent green trees near a blue lake there stood a dazzling white marble palace from ancient times.20 Its lofty pillars were wreathed with vines, and many swallows had made their nests on top of them. One of those nests belonged to the swallow that was carrying Thumbelina.

“Here is my home,” the swallow said. “But if you want to pick out one of those magnificent flowers down below, I’ll set you down on it, and you will have everything your heart desires.”

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Thumbelina sits on the swallow’s back and soars through the air, gazing at the wonders below her.

ELEANOR VERE BOYLE

The swallow swoops down to deposit Thumbelina on one of the beautiful white flowers growing near his home.

“How lovely,” Thumbelina cried, and she clapped her tiny hands.

One of the great white marble pillars had fallen to the ground and broken into three pieces. The most beautiful big white flowers were growing among them. The swallow flew down with Thumbelina and put her on one of the larger petals. How surprised Thumbelina was to find a tiny man sitting in the middle of the flower, as white and transparent as if he were made of glass. He was wearing the daintiest golden crown on his head, and on his shoulders were the loveliest bright wings. He was not a bit bigger than Thumbelina. He was the flower’s angel. In every flower there lived a tiny man or woman just like him, but he was king of them all.

“My Lord, he’s handsome,” Thumbelina whispered to the swallow. The little prince was rather afraid of the swallow, for the bird was gigantic compared to him. He himself was so tiny and delicate. But he was elated when he saw Thumbelina, for she was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen. No one was surprised that he took off his golden crown and placed it on her head. He asked if he might know her name and wanted to know if she would be his wife. Then she could become queen of all the flowers. Yes, he would certainly make quite a husband—not at all like the toad’s son or the mole with his black velvet coat. And so Thumbelina said yes to the handsome prince, and from every flower a tiny lady or a tiny gentleman appeared, each bearing a gift for Thumbelina. But the best gift of all was a pair of beautiful wings from a big white fly. They were fastened to Thumbelina’s back so that she could also flutter from one flower to the next. Everyone rejoiced, and the little swallow sat in his nest and sang the nicest songs he could for them. But deep down in his heart he was sad, for he was so fond of Thumbelina that he never wanted to be parted from her.

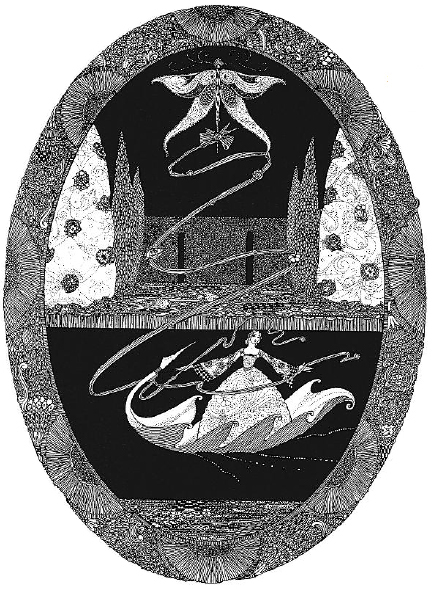

HARRY CLARKE

The swallow bids farewell to Thumbelina, while she and the prince are surrounded by flowers of dazzling beauty on a moonlit night.

“Your name will no longer be Thumbelina,” the flower’s angel told her. “It’s too ugly a name for someone as beautiful as you are. We shall call you Maya.”21

“Farewell! Farewell!” said the little swallow as it flew away from the warm lands back to faraway Denmark, where he had a little nest above the window of the man who can tell you fairy tales.22 To him the bird sang, “Tweet, tweet! Tweet, tweet!” and that’s how we heard the whole story.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

1. an old witch. The designation “witch” does not always signify evil in Andersen’s works: The witches in “The Snow Queen” and “The Tinderbox,” for example, are not particularly wicked or nasty. In “The Wild Swans” and “The Little Mermaid,” however, witches have malevolent designs on the heroine. This particular witch seems to function as a midwife with magical means at her disposal to help the childless woman. In some English translations, the childless woman at the beginning of the tale is turned into a couple without children. The woman and witch both disappear quickly, but one illustrator has depicted the woman and witch as doubles, thereby suggesting that “Thumbelina’s story is the imaginary projection of a childless woman longing for a child” (Nikolajeva and Scott, 48).

2. “grain of barley.” With its countless references to a world divided between an underground realm and a domain of bright sunshine, “Thumbelina” contains a number of allusions to the myth of Demeter and her daughter Persephone. Persephone is abducted by Hades to become goddess of the underworld, and her distraught mother, goddess of agriculture, goes into deep mourning, turning the earth into a site of barren misery. Persephone is returned to her mother, but, each year, she must return to Hades for a period of several months, during which the earth yields no harvest. In this context, it is worth noting that barley seeds planted in the ground during Persephone’s absence come to naught because of the goddess’s anger. In Greek mythology, children of the soil (Cecrops and Erichthonius, for example), or Autochthons, were creatures born of the earth, without mother or father. Folklore contains many examples of children born in nutshells, peppercorns, hazelnuts, and groves of bamboo.

3. she was no taller than a thumb. Diminutive figures are common in folklore, and they are often described as being the size of a thumb, hence the terms Tom Thumb, Thumbkin, Thumbling, and Thumbelina. Many tales featuring boys repeat the terms of the David and Goliath story, but Thumbelina is characterized by beauty, fragility, and vulnerability (rather like the princess in “The Princess and the Pea”) as well as by her small stature. Illustrators have depicted her in a variety of ways, occasionally as an infant, sometimes as a sylphlike child, and even as a miniature grown woman.

4. a voice as soft and sweet as hers. Thumbelina is not only visually attractive but also possesses an enchanting voice. The many references to the chirping of birds makes it clear that Thumbelina and the swallow she rescues are linked by song.

5. a hideous toad hopped in through the window. In fairy tales rooted in ancient cultures, toads and frogs often function as benefactors, for they were seen as symbols of fertility, regeneration, and rebirth. Ancient Egypt, for example, associated frogs with renewal, and the water goddess Heket was represented as a woman with the head of a frog. Egyptian women often wore amulets in the form of frogs to honor the midwife goddess Hegit. In European folklore, by contrast, toads and frogs are commonly presented as hideous creatures that arouse feelings of revulsion, as in “The Little Mermaid,” which describes a toad feeding from the mouth of the Sea Witch. The Grimms’ “Frog King” inaugurated a tradition of repulsive frog suitors by showing a princess pursued by an amorous amphibian, who demands to dine with her, sleep with her, and be her companion. There are many European and Slavic versions of tales about benevolent frog princesses who assist humble young bumpkins in their pursuit of wealth and power. The animal bride in all variants of that tale type is a humble, charming, and generous creature who turns into a young woman of radiant beauty once the spell is broken.

6. “Ko-ax, ko-ax, brekke-ke-kex!” was all he could say. The toad, unlike his mother, who has the power of human language, can utter only cacophonous noises that make him all the more frightening. Thumbelina’s sweet voice and her ability to sing lullabies form a powerful contrast to the disruptive, unattractive sounds that issue from the toad’s throat. The associations with mud and dirt of the earthbound and waterbound toad position him as a creature standing in opposition to the melodious birds encountered by Thumbelina during her journey.

7. the lily pad began to float downstream. As Clarissa Pinkola Estés points out in Women Who Run with the Wolves, fairy-tale figures frequently encounter magic objects with “transportive and sensory abilities that are apt metaphors for the body, such as magic leaf, carpet, cloud.” Cloaks, helmets, boots, and hats also often provide mobility and magical powers: “Each enables the physical body to enjoy deepened insight, hearing, flight, or protection of some sort for both psyche and soul” (Estés, 205). The ordinary comes to be invested with the extraordinary, and the magic object has the power to transport not only the body but also the senses.

In 1874, many years after writing “Thumbelina” and just a year before his death, Andersen complained about a sense of depletion and loss of motivation by referring to how the sight of a lily pad reminded him that he had already exhausted its power to inspire him: “If I see the broad leaf of a water lily, then Thumbelina has already ended her journey on it” (Rossel 1986, 119).

8. soon Thumbelina was traveling abroad. Thumbelina escapes her domestic prison and makes her way out into the same “wide world” that Gerda entered in “The Snow Queen.” Open to adventure and eager to explore, Thumbelina has traded a sheltered existence that will drag her down into muddy foulness for an audacious journey that will expose her to risk but will also let her see the beauty of the world.

9. A lovely little white butterfly. As a symbol of transformation and renewal as well as of death and rebirth, the butterfly helps Thumbelina flee her muddy prison and begin a new life, one marked by a turn in her fortunes. Liberated from an earth-bound existence, Thumbelina joins with the butterfly to enter airy, spiritual domains. The butterfly, long associated with the human soul, also symbolizes the magnificence of an unworldly life. Characterized by beauty (“lovely”), daintiness (“little”), and innocence (“white”), the butterfly is almost like a double of the heroine and anticipates her elevation from an earthbound life to one characterized by regal splendor and the ability to fly.

10. even if she didn’t look at all like a beetle. Social acceptance is always based on conformity in the worlds constructed by Andersen, and Thumbelina—for all her charm and beauty—cannot overcome differences in appearance. Andersen provides a critique of conformity in the encounter between girl and beetles by reversing and defamiliarizing the commonplace revulsion of humans for insects with a chorus of complaints from beetles about the revolting features of humans.

HARRY CLARKE

The butterfly pulls Thumbelina along the water in her lily-pad boat.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Thumbelina is terrified as she flies through the air, carried by a beetle. This flight contrasts strikingly with her magically absorbing journey on the swallow’s back.

11. She was terribly cold. Like the ugly duckling and the little match girl, Thumbelina experiences not only the cruel ordeal of exile and abandonment but also the harshness of the climate. This double exposure to emotional degradation and bodily mortification is Andersen’s trademark, and only the intensification of the condition leads to its reversal.

12. “you must keep my house nice and clean.” Thumbelina’s travels are followed by a period of domestic hibernation in the stillness of an underground world. Like many of her female folkloric cousins, most notably Vasilisa (the Snow White and Cinderella of Russian folklore) and the heroine of the German “Mother Holle” (a Cinderella who proves her worth by carrying out domestic chores under the tutelage of the title figure), Thumbelina finds shelter in a sphere associated with both domesticity and death. She undergoes an apprenticeship, in which she puts on display her ability to care for things. It is no accident that Thumbelina first makes a pact that requires her to care for things, then discovers her power to care for living beings and to heal them. The move from the domestic to the restorative is seamlessly woven into Thumbelina’s underground experiences.

13. “He has such a lovely black velvet fur coat.” Like Hades, the mole is cloaked in black and lives underground, preferring darkness and gloom to sunshine and light. The division of the earth into three regions ruled by three deities (Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades) is taken up and mapped anew in zoological terms. Moles and mice inhabit the nether world; toads and fish dominate the land and the seas; birds and butterflies soar into higher regions. Just as Hades was referred to as “the Rich One” because he possesses the treasures of the earth, so too the mole is described as a creature of great wealth (and great learning as well). Although Thumbelina finds shelter and safety with the mouse, she encounters underground a second suitor who is charged with qualities more lethal than those of the toad. Women writers from Mary Shelley to Muriel Rukeyser have used the myth of Persephone to describe the dark side of female sexual initiation, mapping the consequences of “abduction, rape, the death of the physical world, and sorrowful separation from female companions” (Gilbert and Gubar, 504).

14. “You’ll have to tell him the most enchanting stories you know. ” The mole’s blindness to visual beauty draws attention to his dark side and his inability to appreciate higher values—he does not care for the sun or for flowers. Still, he is enchanted by Thumbelina’s voice when she sings songs to him. Although Thumbelina withholds stories from the mole, she agrees to use her voice, singing children’s songs that were popular in Andersen’s day.

15. he was a mole. Simon Meisling, the headmaster at the school Andersen attended in Slagelse, has been seen as the model for the mole. A classical scholar, Meisling treated others miserably and told Andersen he was a “stupid boy” who would never succeed in life. Cai M. Woel, in his biography of Andersen, provides the following description that hints at an identification between the mole and Meisling: “below average height with a very round head . . . his mouth thin, his nose bulbous. . . . His body was plump with a protruding stomach, big flat feet and short arms. . . . Something about the man’s appearance made you think about the underworld. His hands hardly ever touched water; they were so black that a quick glance would make you think he was wearing gloves” (Frank and Frank, 76–77).

16. you could see the dead swallow. On a trip to Greece in 1841, Andersen’s attention was drawn by a shipmate to “a little bird, who lay among the coiled ropes on the deck, so exhausted it couldn’t even lift its wings. . . . I became quite irritated with the Roman cleric, because he wanted to cook it straightaway. . . . One of the Lieutenants took care of the bird, gave it bread crumbs and water, and it was our guest for the whole day, indeed for the night too. It did not fly away until the next day, chirping as it went, as though in thanks for the kind reception” (Travels, 134).

In Danish folklore, the swallow is known as the svale and was said to have received its name from chirping “Svale, svale” (Cheer up, cheer up) when it flew around the suffering Christ on the cross. The swallow is part of many different folkloric traditions, but it is, above all, associated with springtime. The moribund bird can be seen, in this instance, as both a symbol of winter’s petrifying and deadening effects and a reminder of Christ’s entombment before his resurrection. Oscar Wilde revived the swallow as a symbol of freedom in his fairy tale “The Happy Prince,” which contains multiple allusions to Andersen’s tales.

17. “I’ll take good care of you.” Thumbelina cares for the swallow, bringing him back to life through her tender ministrations. When we learn that the swallow tore his wing on a thorn bush (a possible allusion to Christ’s crown of thorns), it becomes evident that there are biblical undertones to Thumbelina’s nurturing efforts. Not-withstanding a pagan emphasis on nature qua nature and allusions to mythical beings, Andersen’s story also refers repeatedly to Christ’s suffering and resurrection and to the Christian notion of salvation.

18. “Just tie your sash around me.” A second time Thumbelina is rescued by a winged creature, but on this occasion she is able to soar rather than skim the surface of the waters. The swallow is able to lift her into airy regions that put an end to the manifold risks on land and sea as well as underground.

19. poked her little head out to gaze at all the wondrous sights below her. In 1906, the Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf (the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature) published part one of The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, a storybook commissioned by the National Teachers’ Association to teach geography to schoolchildren. Lagerlöf’s Nils Holgersson, alone at home and obliged by his parents to read the script of a church service he is missing, falls asleep and awakens to find that an elf is making mischief in the household. Outwitted by the creature, he is turned into an elf himself and finds that he has the ability to communicate with animals. Wild geese take him on a trip across Sweden, and, in the course of his “wonderful adventures,” Nils (or Thumbietot) receives many lessons in the geography of his native land and also learns that humans do not have the world to themselves. Nils’s adventures were no doubt inspired in part by Thumbelina’s journeys.

20. a dazzling white marble palace from ancient times. Where has Thumbelina landed? Andersen was probably alluding to Italy, where he had traveled the year before. Since the swallow returns to Denmark, Thumbelina has clearly found a home in foreign regions, one that can also be seen as a kind of fairyland or even a realm of death, inhabited by angels.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Thumbelina receives a pair of wings and is able to fly on her own.

21. “We shall call you Maya!” The renaming signals that Thumbelina has developed a new identity, living in a world where she is no longer diminutive. The transformation takes her from adolescence to marriage and moves her from the condition of being a perpetual misfit to membership in a community of kindred spirits. In Hinduism, Maya represents the manifold appearance of the world of phenomena, a world of illusion that obscures the spiritual reality from which it emerged.

22. the man who can tell you fairy tales. The coda embodies the two narrators (the mellifluous bird and the Danish writer) and is reminiscent of the conventions of oral storytelling. At the end of the tale, tellers find a way of drawing attention back to themselves and to the origins or consequences of the stories they tell. The writer’s association with the swallow suggests his existential kinship with Thumbelina, a creature who experiences hardship as a misfit.