Den standhaftige tinsoldat

Among the favorite paper cuttings that Andersen fashioned for his upper-class and aristocratic hosts was a row of soldiers and ballerinas. He once presented these linked figures to Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria, who wondered if his own collection of tin soldiers (which contained three soldiers without heads) might inspire Andersen. Just as the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen challenged Andersen to write a story about a darning needle (and Andersen obliged), Prince Ludwig imagined that it would not be difficult for Andersen to animate his soldiers. Andersen wrote this tale at a time when he was deeply absorbed in the conflict between life and art. He published Only a Fiddler, a novel that charted the suffering of young artists, the same year he wrote “The Steadfast Tin Soldier.”

The soldier and the ballerina in Andersen’s story are incapable of movement and expression, but the soldier has, nonetheless, become a symbol of fortitude in the face of adversity. Like the ugly duckling, he endures all manner of assaults from humans and from the forces of nature, but he also has a romantic side, pining for a ballerina who fails to acknowledge his devotion. In the end, theirs is a failed romance, for they prove unable to transcend their inanimate condition: “He looked at her, and she looked at him, but no words passed between them.” They are joined, finally, in death. The tin soldier is, oddly, animated by the narrative voice that gets inside his head, and—stiff, rigid, and unresponsive throughout the story—he may be steadfast only because he has no other choice but to stand at attention. Still the substance into which the soldier is transformed in the end points to the possibility that he may embody something more than just pure matter.

“The Steadfast Tin Soldier” has inspired many dramatic and musical enactments, among them A Fairy Tale in Pictures, choreographed by Andersen’s contemporary Bournonville. Georges Bizet’s Jeux d’Enfants contains within it “The Steadfast Tin Soldier,” and the musical work was taken up by George Balanchine in 1975. Balanchine’s ballet allowed the soldier and the dancer to encounter and express their love just before the ballerina is blown into the fire. “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” was also adapted for Fantasia 2000, and in it the tin soldier’s adventures are accompanied by the music of Dmitri Shostakovich. The jack-in-the-box (or troll) ends up in the fire, and the soldier and the ballerina survive. The ballerina, who appears to be made of porcelain, gives the soldier a kiss for rescuing her. Even more recently, Kate DiCamillo’s The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane (2006) takes up many of the themes enunciated in Andersen’s tale.

Once upon a time there were twenty-five tin soldiers. They were all brothers, for they had been born of the same old tin spoon. They held their rifles at their shoulders, and they looked straight ahead, splendid in their red and blue uniforms.

When the lid was lifted from the box that held them, the very first words they heard in this world were: “Tin soldiers!”1 That’s what a small boy shouted as he clapped his hands for joy.2 The soldiers were a birthday gift, and he took them out of the box right away and lined them up on the table.

HARRY CLARKE

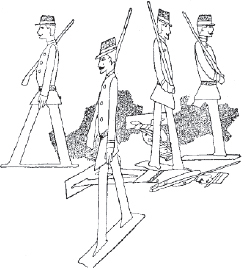

The tin soldier stands at attention while the troll barks at him to stop staring at the beautiful ballerina. Behind the ballerina is the design of a fan; the tin soldier is associated with the architecture of the town; and the troll has risen out of the box that normally contains him.

All of the soldiers looked exactly alike, except for one that was slightly different,3 for he was the last to be cast. There hadn’t been enough tin for a whole soldier, and so he had only one leg. But there he stood, as steady on the one leg as any of the other soldiers on their two. And, just wait and see, he’s the one who turned out to be astonishing.4

There were many other toys on the table with the soldiers, but the most appealing one was a charming castle made of cardboard.5 Through little windows you could look right inside it. In front of the castle were miniature trees surrounding a little mirror that was meant to be a lake. Swans made of wax were swimming on its surface, and their reflections appeared in the mirror. All this was truly enchanting, but more enchanting than anything else was a little lady who was standing by the open entrance to the castle. She had been cut from paper, but she was wearing a dress of the finest tulle. A thin blue ribbon was draped over her shoulder as a scarf, and right in the middle of it shone a spangle that was the size of her tiny face. The little lady held both her arms outstretched, for she was a dancer, and one leg was lifted so high in the air that the tin soldier couldn’t see it at all, and he imagined that she had only one leg, just as he did.6

“Now there’s a wife for me,”7 he thought. “But she may be too noble for me. After all, she lives in a castle. Here I am, living in a box that has to hold all twenty-five of us. That’s no place for her! Still, I should try to make her acquaintance.” Then he stretched out to his full length behind a snuffbox,8 where he could admire the elegant little lady, who continued standing on one leg without losing her balance.

Later in the evening all the other tin soldiers were put back in the box, and the people living in the house went to bed. Then the toys started to play,9 giving parties, fighting battles, and holding balls. The tin soldiers rattled about in their box, for they too wanted to play but were unable to lift the lid. The nutcracker was turning somersaults, and a pencil began scribbling all over a slate. The toys were making such a ruckus that they woke up the canary, and it started chattering too, in verse, if you can imagine! The only two who didn’t budge were the tin soldier and the little dancer. Without ever swerving from the tip of her toe, she held out her arms, and the soldier was just as steadfast on his one leg. Never once did he take his eyes off her.

Suddenly the clock struck twelve10 and, Bam! the lid of the snuffbox popped open. But there wasn’t a bit of snuff in it. No! out bounced a little black troll. What a tricky little move that was.

“Tin soldier,” the troll shouted. “Keep your eyes to yourself!”

The tin soldier acted as if he had not heard.

“Just wait until tomorrow,” the troll shouted.

When morning came and the children awoke, the soldier was put over by the window ledge. Was it the troll or was it just a gust of wind?11 All of a sudden the window flew open and the soldier went plunging headfirst down four floors. He fell with breathtaking speed—his one leg stuck straight out in the air—landing cap first, with his bayonet thrust right between the cobblestones.

The housemaid and the little boy ran down to look for him, and, even though they nearly stepped right on the tin soldier, they couldn’t see him. Had the tin soldier shouted “Here I am!” they would surely have found him, but he felt it was beneath his dignity to shout while in uniform.12

Before long it began to rain. One drop fell faster than the next and soon it was raining buckets. Just as the rain was letting up, two street urchins came running along.13

“Hey, look!” one of them said. “There’s a tin soldier over here. Let’s send him off to sea.”

The two made a boat from a newspaper, set the tin soldier right in the middle of the boat, and away he sailed down the gutter, with the two urchins running beside him, clapping their hands. Good heavens!14 Who would have thought a gutter could have such powerful waves and strong currents! Don’t forget that there had just been a downpour. The paper boat pitched from side to side, and at times it whirled around so rapidly that the tin soldier trembled and shuddered. But he remained steadfast, without changing his expression and looking straight ahead of him, standing tall with his rifle on his shoulder.

All of a sudden, the boat was washed in under a long plank used to board over the gutter. It became just as dark as it once was inside the box.15

“I wonder where I’ll finally end up,” the soldier thought. “This must be the troll’s revenge. Oh, if only that little lady were sitting here in the boat with me, it could be twice as dark here for all I care.”

Just then a big water rat appeared. He was living under the gutter plank.

“Do you have your passport?” asked the rat. “Let’s have a look.”

The tin soldier kept quiet and gripped his rifle more firmly than ever. The boat sped along, with the rat in hot pursuit, gnashing his teeth as he shouted at the sticks and straws on the path: “Stop him! Stop him! He hasn’t paid the toll! He didn’t show me his passport.”

The current ran stronger and stronger. The tin soldier could already see daylight ahead where the plank stopped, but he also began to hear a roaring sound that would have frightened even the boldest among us. Just imagine: right where the plank ended, the gutter led right into a huge canal. It was as dangerous for the soldier as a waterfall would be to us.

The tin soldier was so near the edge that he could not possibly stop the boat in time. It plunged forward. He stood as tall as he could, and no one could say that he so much as blinked an eye. The vessel spun around three or four times and then filled to the rim with water. It began to go under. The water was already up to the soldier’s neck, and the boat started sinking deeper and deeper, with the paper dissolving faster and faster. Water began rushing in over his head. That’s when the soldier thought about the pretty little dancer and how he would never see her again. In his ears, the soldier could hear an old tune:

Flee the waters, warrior brave,

Here below is thy shadowy grave.

The paper boat fell apart, and the soldier plunged right through it. And at that very moment, he was swallowed by an enormous fish.

My! How dark it was inside the fish. It was even darker than under the gutter plank,16 and it was far more cramped. But the tin soldier remained steadfast and stretched out full length, with his rifle on his shoulder.17

The fish thrashed about, making the strangest movements imaginable. Finally it became perfectly still, and then something like a bolt of lightning flashed through it. The soldier saw daylight again, and he heard a voice cry out: “The tin soldier!” The fish had been caught, taken to market, and then taken to a kitchen where the cook was cutting him open with a big knife. She picked the soldier up between her two fingers and took him into the parlor, where everyone wanted to see the remarkable traveler18 who had taken a voyage in the belly of a fish. But the tin soldier was feeling anything but pride. They put him on a table and—lo and behold—what strange things can happen in the world. There he was, back in the same old parlor he had left. There they all were, once again: the children, the toys on the table, and the lovely castle with the pretty little dancer. She was still balancing on one leg, with the other raised high in the air. She too was steadfast.19 The soldier felt so moved that he would have wept tears of tin, but soldiers are not supposed to cry. He looked at her, and she looked at him, but no words passed between them. Just then one of the little boys snatched up the soldier and, for no reason at all, threw him right into the stove.20 That old troll in the snuffbox must have put him up to it.

The tin soldier just lay there, in flames. He could feel the terrible heat, but he wasn’t sure whether it was coming from the fire or from love. He had lost his vibrant colors,21 perhaps in pursuit of “transcendent love” than aiming to display his fortitude through his upright position. from his hard journey, but perhaps also from grief, no one could say for certain.

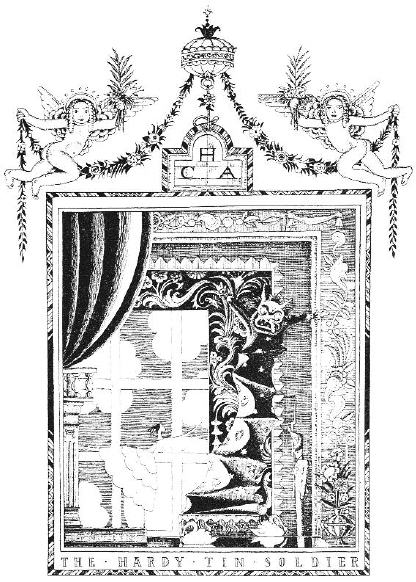

KAY NIELSEN

The tin soldier begins to go up in flames, consumed by the bright fire, while the ballerina seems to be leaping toward him, to her death. Surrounded by a border of hearts, the tale of the two figurines is framed as a love story.

The soldier looked at the little lady, and she looked at him, and he could feel that he was melting. But still he stood steadfast, his musket on his shoulder. Then the door flew open. A gust of wind picked up the dancer,22 and she soared like a sylph right into the fire with the soldier, bursting into flame, and then she was gone. The tin soldier melted into a lump. The next day, when a servant girl was taking out the ashes, she discovered him in the shape of a little tin heart.23 But all that was left of the pretty dancer was her spangle, and it had been burned black as coal.24

1. “Tin soldiers!” Toy soldiers have served as collector’s items and as war toys since antiquity. As Lois Kuznets points out, they can function as “stimuli for the reenactment of historic scenes of hostility, death, bravery, treachery, honor, and patriotism, or as nostalgic memorabilia of such violent (or gallant?) moments” (Kuznets, 76). Originally made by hand from wood, clay, stone, and metal, they were not mass-produced until the end of the eighteenth century, by a Parisian firm named Mignot. Among noted collectors of the “little men” (manufactured by Mignot, Heyde, Britain’s, and other companies) were Winston Churchill and H. G. Wells.

2. he clapped his hands for joy. Although the boy who receives the tin soldiers seems delighted by the gift, he does not appear to bond in any way with the toy, certainly not with the depth of feeling that the tin soldier has for the ballerina. In Andersen’s stories about objects with inner lives, humans are often presented as callous, materialistic beings.

3. except for one that was slightly different. Thomas Mann, a great admirer of Andersen, wove the tale of “The Little Mermaid” into his novel Doktor Faustus. Mann declared in a letter to a friend that he had always identified with “The Steadfast Tin Soldier,” who was “the symbol of my life.” Joyce Carol Oates, in a meditation on writing, quotes Mann and asks whether the choice of story, featuring a soldier who never consummates his love, indicates that writers are “secretly in love with failure” (Oates 2004, 59–60). But Mann may have identified with the “slightly different” nature of the tin soldier and seen in him a symbol of endurance and of the writer’s self-immolating commitment to his craft. Thomas Mann scholar Hans Rudolf Vaget suggests multiple possibilities for the identification, revealing the degree to which the tin soldier represents more than sheer steadfastness: “What might have prompted Thomas Mann to point to this fairy tale hero as the symbol of his life? Was it the soldierly devotion to discipline and order that he both practiced and extolled as a writer? . . . Or was it simply the combativeness of his nature . . . [or] an awareness that, as an artist and a spinner of tales, he served essentially as a kind of toy. It might even have been a secret suspicion that there was a certain tinniness to his role as the artist-soldier” (Vaget, 3).

4. he’s the one who turned out to be astonishing. Although the tin soldier has a deficiency that is connected with mobility, he becomes a heroic wanderer resembling Odysseus or his fairy-tale counterpart Tom Thumb. The disability is emphasized at the beginning of the tale, but it quickly becomes insignificant in light of the fact that the soldier’s fate would not be any different were he to possess two legs. Yet the disability remains important: “narrative embraces the opportunity that such a ‘lack’ provides—in fact, wills it into existence—as the impetus that calls a story into being” (Mitchell and Snyder, 55). The term “astonishing” may refer to the soldier’s adventures but also to the “little tin heart” that becomes the objet d’art at the tale’s conclusion.

5. a charming castle made of cardboard. The castle and its surroundings constitute one of the many architectural wonders and marvelous landscapes found in Andersen’s works. The miniaturization makes the castle appealing, and the artful use of mirrors to create illusions reminds us that we are in the realm of creative wizardry. The swans swimming on the surface, producing reflections, are reminiscent of the ending to Andersen’s “Ugly Duckling.” Finally, the ballet dancer in her beautiful costume stands at the entrance, suggesting that the castle is a monument to art, beauty, and mobility.

6. he imagined that she had only one leg, just as he did. The tin soldier’s feelings of affinity with the tiny maiden are based on an error in perception. The ballerina, although she represents grace and mobility, is made of paper and remains as incapable of movement as the tin soldier, with his single leg. Andersen’s choice of soldier and ballerina is mildly ironic, in that both are associated with movement—marching and dancing. And both are figures to be admired for their display of colors and beauty.

7. “Now there’s a wife for me.” Andersen’s tin soldier leads a strange in-between existence, possessing, like humans, the power to think and meditate about his future, yet also without the mobility that enables humans to act as agents. As one critic puts it: “Andersen’s animated man-made objects inhabit a strange land. They are alive, so it seems; they are personified and equipped with human attributes; they are conscious of their existence; they contemplate their experiences and become wiser for doing so; they are very sensitive creatures. On the other hand, though, they are wrong in assuming they are important to man: they are alive, but they are so much wrapped up in their narcissistic memories that they never realize that they are not free to act” (Schwarcz, 79). The soldier may have consciousness and a voice, but he remains surprisingly unappealing, even if his steadfastness is presented as admirable.

8. behind a snuffbox. Snuff, or powdered tobacco, was imported from North America and introduced to Europeans in the sixteenth century. The use of snuff (inhaling a pinch of tobacco, then sneezing elegantly) became fashionable in Europe, and snuff-taking was seen as a mark of aristocracy in the nineteenth century. Artisans created beautiful containers to hold the tobacco, and the presence of the snuffbox in the home is another sign of a comfortable bourgeois setting.

The novelist Kathryn Davis writes about her childhood reaction to the snuffbox in Andersen’s story: “When I was seven years old I didn’t have a clue what a snuffbox was, but I knew it was the right name for an object that sprang open unexpectedly to release a goblin. ‘Snuffbox’ dropped straight from God’s mouth, where it hadn’t yet acquired meaning, and into my brain. Recognizing its aptness, I participated in its creation” (Davis, 86).

9. Then the toys started to play. The animation of the toys was surely inspired by E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Nutcracker and the Mouse King” (1816), a tale in which toys come to life at midnight. In Hoffmann’s Christmas Eve tale, an army of soldiers, led by the Nutcracker, defeats an army of mice. A nutcracker also appears among the toys in Andersen’s story, and the troll who leaps out from the snuffbox is a diabolical figure resembling Hoffmann’s evil Mouse King. The uncanny effect of toys coming to life is both marvelous and magical yet also dark and sinister, suggesting a grotesque, topsyturvy world in which the mechanical becomes real. Andersen’s story, like Hoffmann’s, locates romance, violence, adventure, and passion in a childhood setting.

KAY NIELSEN

An angry troll seems intent on keeping tin soldier and ballerina apart, while on the surface below him, swans swim toward each other.

10. Suddenly the clock struck twelve. Midnight is, of course, the “witching hour,” the time of night when goblins, ghosts, witches, and other demons emerge to perform their pagan rituals. The black troll who pops out of the snuffbox belongs to Scandinavian folklore and is a figure who cannot tolerate the light of day—hence the fact that he remains, like vampires and other creatures of the night, in the coffinlike snuffbox.

11. Was it the troll or was it just a gust of wind? The rhetorical question is important, for it questions agency and proposes a natural explanation for the soldier’s fall. Given the importance of the elements in the story (water, fire, and air), the question of whether the troll or nature conspires against the tin soldier is an important one.

12. he felt it was beneath his dignity to shout while in uniform. The tin soldier’s pride is not necessarily admirable—in many instances it undermines his chances for survival. But there is an added layer of irony in the fact that the soldier does not have the power to speak, yet rationalizes his silence with the alibi of preserving his military dignity. Here, pride is affiliated with vanity (as in “The Emperor’s New Clothes”), but in this case it leads to stoicism.

13. two street urchins came running along. As is often the case in Andersen’s stories, schoolboys and street urchins can be counted on to engage in sadistic behavior. Saintly urchins like the little match girl are invariably female.

14. Good heavens! With this phrase, the narrator makes it evident that he is presenting an account of the events consonant with his character’s point of view. The exclamation “Good heavens!” reveals the degree to which the thoughts of the narrator and his character merge, creating a narrative situation in which all sympathy is extended to the character.

15. It became just as dark as it once was inside the box. The soldier can be seen as undergoing a rite of passage, a three-part process defined by the renowned anthropologist Arnold van Gennep as separation, transition, and reincorporation. In the second, or “liminal,” stage of transition, the soldier is neither here nor there, existing in a state of “betwixt and between.” Liminality, as Gennep’s disciple Victor Turner emphasized, is frequently “likened to death, to being in the womb, to invisibility, to darkness, to bisexuality, to the wilderness, and to an eclipse of the sun or the moon” (Turner, 95). The soldier himself, whether at home or in the gutter, displays the behavior of neophytes who are in that transitional phase: “passive or humble” and accepting “arbitrary punishments without complaint.” The soldier, unlike the neophyte, does not undergo rebirth and transformation, although he could be said, in the end, to experience a mock reincorporation.

16. It was even darker than under the gutter plank. The tin soldier’s lot is arduous, for he sinks from the comforts of a bourgeois home into the gutter and finally into an even darker and more dangerous site.Andersen scholar John Griffith points out that “frequently the physical ordeal Andersen’s lovers must go through in pursuit of transcendent love is a descent into dark, close, filthy places—the tin soldier floats down a gutter into a sewer and is swallowed by a fish; the shepherdess and the chimney sweep have to creep up and down a chimney flue; the ball and the top meet in a garbage bin where ‘all kinds of things were lying: gravel, a cabbage stalk, dirt, dust, and lots of leaves that had fallen down from the gutter’ ” (Griffith, 83).Andersen’s tin soldier, however, seems less in pursuit of “transcendent love” than aiming to display his fortitude through his upright position.

17. stretched out full length, with his rifle on his shoulder. The soldier is a stoic Jonah, who willingly endures life inside the belly of the fish. George Orwell once described the comforts of living within a creature: “For the fact is that being inside a whale is a very comfortable, cosy, homelike thought. The historical Jonah, if he can be so called, was glad enough to escape, but in imagination, in daydream, countless people have envied him. It is, of course, quite obvious why. The whale’s belly is simply a womb big enough for an adult. There you are, in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens” (Orwell, 177–78). Tom Thumb and Pinocchio undergo similar experiences in the bellies of beasts, domestic and wild.

18. everyone wanted to see the remarkable traveler. The soldier has undertaken the voyage of the hero, returning as a “remarkable” personage who has found his way back home again.

19. She too was steadfast. There is more than a touch of irony to the fact that both soldier and ballerina have no choice but to remain immobile and that the soldier is persuaded that he and the ballerina are kindred spirits because they share the quality of steadfastness.

20. for no reason at all, threw him right into the stove. The soldier seems to be a survivor, but in the end, he loses his life “for no reason at all”—just on a small boy’s whim. The soldier attributes the boy’s urge to an evil power, suggesting that the troll has engineered his death.

21. He had lost his vibrant colors. Like the ballerina, the soldier is a figure on display, with an attractive, multicolored uniform. Ole Shut-Eye, in the story of that title, also wears a suit of many colors.

22. A gust of wind picked up the dancer. Once again, a chance event—the opening of the door and the creation of a draft—leads to death. The ballerina, for all her steadfastness, cannot resist the force of the wind, just as the tin soldier succumbed to it at the beginning of the tale.

23. in the shape of a little tin heart. Given the importance of contingency in the tale, it seems possible that the heart-shaped mass is nothing more than an accident. It is also possible that the tin soldier’s ardor was so powerful that it shaped his remains. Andersen’s paper cuttings often had heart shapes in them.

24. it had been burned black as coal. The transformation of the brilliant spangle into a remnant black as coal contrasts with the conversion of the soldier into a little tin heart. A moral judgment in favor of the soldier is entered through the symbolic nature of the remains.