Ole Lukøie

Ole Shut-Eye is related to the figure of Jon Blund, an elf who sprinkles sand in children’s eyes so that they will go to sleep. Andersen not only substitutes sweet milk for the sand but also turns Ole Shut-Eye into a storyteller, one who needs lights out and eyes shut to work his magic. Ole Shut-Eye is both an incarnation of dreams (with a brother named Death) and an unrivaled storyteller, who understands the importance of stories as a bridge between the real world and the world of imagination.

Ole Shut-Eye is related to the Sandman and Willie Winkie in Anglophone countries, and Dormette in France. Wee Willie Winkie comes from a Scottish nursery rhyme of 1841 written down by William Miller in dialect: “Wee Willie Winkie rins through the toun, / Up stairs and doon stairs in his nicht-goun, / Tirlin’ at the window, cryin’ at the lock, / ‘Are the weans in their bed, for it’s noo ten o’clock?’ ” Wee Willie Winkie and his kin have been used for centuries to frighten, coerce, and entice children to go to bed. Ole Shut-Eye seems the most benevolent of these spirits.

No one in the world knows as many stories as Ole Shut-Eye, and he certainly knows how to tell them!

When night falls, and the children are sitting around the table or on their little stools, behaving well, Ole Shut-Eye arrives. He comes upstairs without making noise, for he has socks on. He opens the door gently, and he flicks some sweet milk on the children’s eyes—just a tiny bit, but enough to make them close their eyes so that they can’t see him. He tiptoes behind them and breathes softly on their necks, making their heads feel heavy. Yes, indeed! But it doesn’t hurt, for Ole Shut-Eye adores children and just wants them to quiet down, and that only happens after they’ve been put to bed. He wants them to be quiet so that he will be able to tell them stories.

As soon as the children have fallen asleep, Ole Shut-Eye sits down at their bedsides. He is well dressed, with a coat made of gleaming silk that changes color as he turns around, first red, then green, then blue. Under each arm he holds an umbrella. One has pictures all over it, and he opens that one up over good children. They dream the most beautiful stories all night long. The other is just a plain umbrella with nothing on it at all, and that one he opens over naughty children. They are restless and can’t sleep, and when they wake up in the morning they have had no dreams at all.1

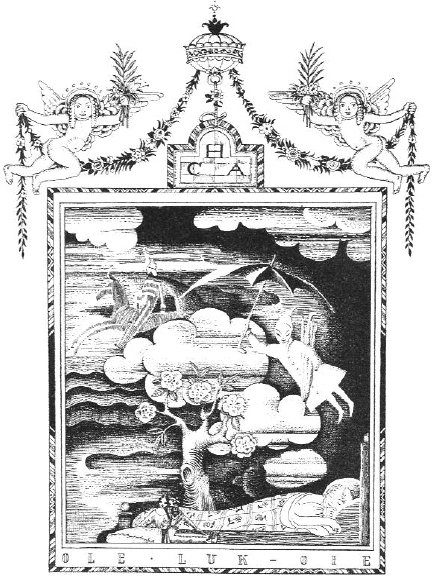

KAY NIELSEN

Hjalmar lies peacefully in bed, with his dolls at the foot of the bed. Above him Ole Shut-Eye has opened an umbrella that will enable him to have beautiful dreams.

Now you shall hear about how Ole Shut-Eye came every day of the week to a little boy named Hjalmar and about all the things he told him. There are seven stories in all, because there are seven days in the week.

“Now listen up,” Ole Shut-Eye said one night after he had managed to get Hjalmar to go to bed. “First of all, I’m going to spruce things up.” And before long all the flowers in their pots had grown into big trees, with their long branches arching across the ceiling and back down along the wall until the room had become a beautiful bower.2 The branches were covered with flowers, each prettier than a rose and with a fragrance so sweet that, if you tasted it, it was sweeter than jam. The fruit gleamed like gold, and there were also buns bursting with raisins. No one has ever seen anything like it! 3

Suddenly you could hear a dreadful howling over in the drawer where Hjalmar kept his schoolbooks.4

“What could that be?” Ole Shut-Eye asked, as he went over to the desk and opened the drawer. The slate was throwing a fit and was about to fall apart. A sum would not come out right because an error had slipped into the calculations. The pencil was tugging and leaping at the end of its string like a little dog. It wanted to correct the sum but didn’t know how.

Then Hjalmar’s copybook started howling as well. It was just dreadful to hear. On each page, capital letters ran down the page, with lowercase letters right next to them, a complete column of them all the way down. They were the models, and next to them were letters that believed they looked just the same. Hjalmar had written those, and they looked as if they had tripped over the straight line, where they were supposed to be.

“Look here—this is how you are supposed to stand,” the model said. “See this—sloping a bit, then with a bold stroke.”

“Oh, we would be glad to,” Hjalmar’s letters replied. “But we can’t. We’re so weak.”

“Then you will have to take some medicine!” Ole Shut-Eye replied.

“Oh, no,” they shouted, and suddenly they stood up as straight as you would want them to be.

“No time for stories now,” said Ole Shut-Eye. “I have to put them through their paces. Left, right! Left, right!” And he drilled the letters until they were just as elegant and straight as their models.5 But after Ole Shut-Eye had left and when Hjalmar looked at them the next morning, they were just as miserable as before.

TUESDAY

As soon as Hjalmar was in bed, Ole Shut-Eye sprinkled his magic potion on all the furniture in the room, and every piece began chattering.6 They all talked about themselves except for the spittoon, which kept quiet. It was annoyed that all the others were so self-centered and constantly talking and thinking only of themselves, without paying the least bit of attention to it, sitting so humbly in the corner and allowing others to spit in it.

A large painting in a gilt frame was hanging above the chest of drawers. It showed a landscape with tall old trees, flowers growing in a meadow, and a large lake from which a river flowed away through the woods, past many castles, far out to the open sea. Ole Shut-Eye used his magic spray on the painting,7 and birds began to sing. The branches stirred in the trees, and clouds billowed out. You could see their shadows moving across the landscape.

Ole Shut-Eye picked little Hjalmar up and put him right at the edge of the painting so that he could step into the painting and stand in the tall grass, with the sun shining down on him through the branches of the trees. He ran down to the water and climbed into a little boat that was right there. It was painted red and white, and its sails shone like silver. Six swans, all with golden crowns down over their necks and bright blue stars on their foreheads, towed the boat past the green woods, where the trees were telling tales about robbers and witches,8 and the flowers were whispering about dear little elves and about what butterflies had told them.

KAY NIELSEN

Hjalmar sails on a placid river, accompanied by swans. A princess extends a treat to him from the balcony of a radiant castle on the riverbank.

Lovely fish with scales that seemed like gold and silver swam after the boat, leaping up now and then so that the water started to speak in splashes. Birds red and blue, large and small, flew behind the boat in two long lines. Gnats danced and May bugs went boom, boom! They all wanted to go with Hjalmar, and every one of them had a story to tell.

What a magnificent voyage it was! At times the woods were dark and deep, and then suddenly they turned into the loveliest garden filled with flowers and sunshine. You could see palaces of marble and glass, with princesses on their balconies. Hjalmar knew all of them well, for they were his playmates. They stretched their hands out to him, offering him the prettiest sugar pigs that any cake woman had ever sold. Hjalmar caught one end of a sugar pig as he sailed by, and the princess held on tight to the other end, so that each was left with a piece. The princess had the smaller piece, and Hjalmar had the larger one. Little princes with gold swords stood guard at the palaces and saluted. They showered Hjalmar with raisins and tin soldiers. You could tell that they were real princes!

Sometimes Hjalmar sailed through forests, sometimes through what seemed to be great halls, or even straight through towns. That’s how he arrived in the town where his nanny lived, the woman who had looked after him when he was a small boy.9 She had been very fond of him, and now she nodded and waved, singing the pretty verses she had made up on her own and sent to Hjalmar:

Once I kissed your eyes so clear

And held you tight

Both day and night.

I heard your words and saw your tears,

Then good-byes after tender years.

God keep you near as you grow wise,

My joyous herald from the skies.

Birds joined in her songs, and the flowers began keeping time on their stalks. And the old trees nodded, just as if Ole Shut-Eye were telling them stories too.

WEDNESDAY

Goodness, how it was pouring outside! Hjalmar could hear the rain in his sleep, and when Ole Shut-Eye opened the window, water splashed right onto the windowsill. There was a lake right outside the window, and a fine ship right beside the house.

“Hjalmar, my boy, are you ready to go?” Ole Shut-Eye asked. “We can travel to distant lands tonight and be back by morning.”

All at once Hjalmar was in his Sunday best on board the splendid ship. The weather had turned glorious as they sailed through the streets, rounded the church, and steered toward the open seas. They sailed on and on until you could no longer see land, and they met a flock of storks, who were also leaving home, bound for warmer climes. They had been flying in one long line, and had already covered a great distance. One of them was so weary that his wings could scarcely keep him in the air. He was the very last in the line, and, before long, he had been left behind by the others. He began to sink lower and lower, his wings still spread out, trying to make a few more feeble strokes, but it was no use. His feet touched the ship’s rigging; he glided down the sail, and, plop! There he was on the deck.10

The cabin boy picked him up and put him in the chicken coop with the hens, ducks, and turkeys. The unfortunate stork looked miserable among them.

“What a funny-looking fellow,” the hens declared.

And the turkey puffed himself up as big as he could and asked the stork who he was. 11 The ducks backed off and nudged each other: “Start quacking! Keep it up!”

The stork began to tell them about how hot it was in Africa, about the pyramids, and about ostriches that can run across the desert like wild horses. But the ducks could not understand what he was saying and again they nudged each other: “We all agree, don’t we, that he’s a fool.”

“Yes, a real fool,” the turkey declared with a “gobble, gobble,” while the stork kept silent and turned his thoughts to his beloved Africa.

“Those are nice thin legs you have,” the turkey said. “How much are they a yard?”

“Quack, quack, quack,” chuckled the ducks, and the stork pretended not to hear.

“You may as well join in,” the turkey told him, “for that was a really witty remark, but maybe it went over your head! No, indeed, he is not very bright, so we will have to rely on ourselves for fun.”

The hens clucked away, and the ducks kept on quacking. It was dreadful to see how they made fun of him among themselves.

Hjalmar went over to the chicken coop door and called over to the stork, who hopped out on the deck. He had had a chance to recover, and it looked as if he was thanking Hjalmar by nodding in his direction.12 Then he spread out his wings and flew away to the warm countries. The hens went on clucking, the ducks quacked, and the turkey gobbled until he was red in the face.

“Tomorrow we shall make a soup out of you,” said Hjalmar, and then he woke up in his own little bed. The voyage arranged by Ole Shut-Eye had been truly astonishing.

THURSDAY

“What’s next?” Ole Shut-Eye asked.

“Now don’t be afraid if I show you a little mouse.” And there sat the quaint little creature, right in Ole Shut-Eye’s hand. “It has come,” he said, “to invite you to a wedding. Two little mice are about to enter the state of holy matrimony tonight. They are living under the wooden boards in your mother’s pantry in a most charming little flat.”

“How will I ever be able to squeeze through that tiny mouse hole in the floor?” Hjalmar asked.

“Leave that to me,” Ole Shut-Eye said. “I’ll make you small enough.” And as soon as he used some of the magic spray on Hjalmar, the boy became smaller and smaller13 until he was no taller than your finger. “Now you will be able to wear the tin soldier’s uniform.14 It should fit perfectly, and uniforms are always so smart for parties.”

“Rather!” Hjalmar said, and the next moment he looked like the most dashing tin soldier.

“If you’ll kindly be seated in your mother’s thimble,” the mouse said, “I shall have the honor of pulling you.”

“Are you really willing to go to all that trouble?” Hjalmar cried out. And, with that, he was whisked off to the mouse wedding.

At first they went down a long passage under the floorboards. There was just room enough for them to drive through in the thimble, and the whole passage was lit up with touchwood.15

“Doesn’t it smell delightful here?” said the mouse. “This whole road has been greased with bacon rinds, and nothing can beat that.”

Then they entered the wedding hall. To the right stood all the little lady mice, whispering and giggling as if they were making fun of each other. To the left stood all the gentlemen mice, twirling their mustaches with their forepaws. The bridegroom and bride stood in a hollow cheese rind in the center of the floor and began kissing each other like mad, in plain view of all the guests. Well, after all, they were engaged and about to be married.

Guests kept arriving, and the mice were nearly trampling each other to death. The bridal couple had posted themselves in the doorway, so that no one could come in or go out. Like the passage, this whole hall had been greased with bacon rind, and that was the complete banquet. But for dessert, a pea was carried in. A little mouse in the family had gnawed the name of the bridal couple on it—or at least the first letter of the name. That was really something out of the ordinary.

The mice all agreed that it had been a charming wedding, and all the conversations had been just perfect. Hjalmar drove back home again. He had spent time in very smart society, but he had had to put up with no end of shrinking in order to be small enough to fit in that tin soldier’s uniform.

FRIDAY

“It’s amazing how many grown-ups are anxious to get hold of me,” Ole Shut-Eye said. “Especially the ones with bad consciences. ‘Dear little Ole,’ they tell me, ‘we can’t shut our eyes. We lie awake all night long staring at our wicked deeds sitting on the edge of the bed like ugly little goblins and making us soak in perspiration. Can’t you chase them off so that we can have a good night’s sleep?’ And then they add with a deep sigh: ‘We’re only too glad to pay. Good night, Ole. The money’s on the windowsill.’ But I don’t do anything for money,” Ole Shut-Eye declared.

“Well, what should we do tonight?” little Hjalmar asked.

“I’m not sure if you care to go to another wedding. But it will be quite different from last night’s. Your sister’s big doll, the one that looks like a man and is named Herman, is supposed to marry a doll named Bertha. It’s Bertha’s birthday too, and that means there will be presents galore.”

“Yes, I know what that means,” Hjalmar said. “Whenever the dolls need new clothes, my sister lets them have a birthday or a wedding. It’s happened at least a hundred times already.”

“And tonight’s wedding is the one hundred and first, and when this one’s over, there won’t be any more. That’s why it’s going to be so splendid. Just take a look.”

Hjalmar looked over at the table. He could see a little cardboard house with lights in the window. Tin soldiers were presenting their arms outside it. The bride and bridegroom were seated on the floor, leaning up against the leg of the table and looking very thoughtful, and with good reason. Ole Shut-Eye, rigged out in Grandmother’s black petticoat, conducted the ceremony. When the wedding was over, all the furniture in the room joined in to sing the following beautiful song, written for the occasion by the pencil, and sung to the tune of the soldier’s tattoo:

Our song will greet through wind and weather

These two that love has brought together.

Neither knows quite what’s been done,

And who’s to say what has been won?

Wood and leather blend together,

Hurrah for them in wind and weather!

Next came the wedding presents. The pair said that they didn’t need any food at all, because they were planning to live on love.

“Shall we go to the country, or would you rather travel abroad?”16 the bridegroom asked. They consulted the swallow, who was a great traveler, as well as the old hen, who had hatched five broods of chicks. The swallow described the lovely warm countries, where grapes hang in heavy, ripe bunches, and where the air is soft. The colors on the mountains are something we never see here.

“Still, they don’t have our green cabbage,” the hen declared. “I once spent the summer with all my chicks in the country. There was a gravel pit there in which we could scratch all day, and then we had the use of a garden where there were cabbages. Oh, how green they were! I can’t imagine anything more lovely!”

“One cabbage looks just like the next,” the swallow said. “And the weather is often so bad here.”

“Oh, well, we’re used to that,” the hen replied.

“But it’s so cold here. It’s often freezing.”

“That’s good for the cabbage,” said the hen. “And besides, we have warm weather at times. Don’t you remember that hot summer we had four years ago? It was so hot for five weeks that you could barely breathe. Then too, we don’t have all those poisonous creatures that live abroad. And we don’t have robbers.17 Anyone who doesn’t believe that ours is the most beautiful country is a scoundrel who doesn’t deserve to live here!” Tears came into the hen’s eyes. “I’ve done a bit of traveling myself. I once made a twelve-mile trip in a coop, and there was no joy in it at all.”

“That hen is a sensible woman!” Bertha the doll said. “I don’t fancy traveling in the mountains either, because all you do is go up and then down. No, let’s move to the gravel pit and take walks in the cabbage patch.”

That settled the matter.

SATURDAY

“Any stories tonight?” little Hjalmar asked, as soon as Ole Shut-Eye had got him to bed.

“We haven’t time this evening,” Ole told him, as he opened his umbrella with the prettiest pictures on it. “Take a look at these Chinese figures.” The entire umbrella looked like a large Chinese bowl, with blue trees and arched bridges, with little Chinese figures nodding their heads.

“We must have the whole world spruced up18 by tomorrow morning,” Ole Shut-Eye said. “You see, it’s Sunday, a holiday. I have to go over to the church tower to make sure that the little church elves are polishing the bells so that they will sound their best. I must check the fields to make sure that the wind is blowing the dust off the leaves and grass, and then there is my hardest task, taking down all the stars and polishing them. I put them in my apron, but, before that, I have to number each one along with the place it comes from so that they can return to their proper places, otherwise they won’t fit tight and we would end up with too many shooting stars, because one after another would come tumbling down.”

“Oh, I say here, Mr. Shut-Eye,” an old portrait hanging on the wall of Hjalmar’s bedroom said. “I am Hjalmar’s greatgrandfather. Thank you for telling the boy your stories, but you mustn’t put strange ideas in his head. The stars can’t be taken down and polished. The stars are globes just like the earth. That’s the beauty of them.”

“Thanks very much, Great-grandfather,” Ole Shut-Eye said. “I’m grateful to you. You are the head of the family, of course, the Grand Old Man, but I’m even older than you are. I’m an ancient heathen. The Greeks and Romans called me the Dream God. I visit the homes of the best families all the time. I know how to get along with all kinds of people, big and small. Now you may tell the stories on your own.” Ole Shut-Eye picked up his umbrella, and off he went.

“Well! Nowadays you can’t even express an opinion,” the old portrait grumbled.

And just then Hjalmar woke up.

“Good evening,” Ole Shut-Eye said, and Hjalmar nodded, and then he turned his great-grandfather’s portrait to the wall so that it wouldn’t interrupt them, as it had the night before.

“Please tell me some stories,” he said. “The one about the five peas living in a pod, the cock-a-doodle-doo that courted the hen-a-doodle-doo, and the darning needle who gave herself such airs19 because she believed she was a sewing needle.”

“That might be too much of a good thing,” said Ole Shut-Eye. “I’d rather show you something. In fact, I’m going to introduce you to my own brother.20 He is also named Ole Shut-Eye, but he never comes more than once to a person. When he comes, he takes you for a ride on his horse and tells you stories. He only knows two: one is more beautiful than anyone on earth can imagine, and the other is so ghastly that it’s beyond description.”

Ole Shut-Eye lifted Hjalmar up to the window and said: “Look, there’s my brother, the other Ole Shut-Eye. He’s also known as Death. You can see that he doesn’t look nearly as bad as he is made out to be in pictures, where he is nothing but a skeleton. No, his coat is embroidered with silver. It’s like the magnificent uniform of a hussar, with a cloak of black velvet billowing behind him over his horse. See how he gallops along!”

Hjalmar saw the other Ole Shut-Eye riding away, carrying both young and old on his horse. He placed some in front of him, others behind, but he always asked them first: “What does it say in your report card?” “Good,” they all replied. Then he would say: “Let me see for myself.” And then they had to show him the cards, and the ones who had “very good” or “excellent” would get to ride in front of him and hear a beautiful story.21 But those who had “mediocre” or “poor” had to ride behind him and hear a ghastly tale. They trembled and sobbed and tried to jump off the horse, but they couldn’t do that because they were stuck fast to it.

“Why, Death is a most wonderful Ole Shut-Eye,” Hjalmar exclaimed. “I’m not at all afraid of him.”

“No, you needn’t be,” Ole Shut-Eye told him. “But be sure that you always have a good report card.”

“Most enlightening!” the portrait of Great-grandfather muttered. “It does some good, after all, to speak your mind.” And he was quite satisfied.

There! That’s the story of Ole Shut-Eye. Tonight he can tell you some more himself.

1. they have had no dreams at all. Ole Shut-Eye, like Santa Claus and other benevolent figures, differentiates between naughty and nice, providing an instructive moral example in this bedtime story. Being deprived of the beautiful images in bedtime stories proves to be a powerful punishment, but not quite as bad as the one for “poor” or “mediocre” marks in school, as described at the end of the tale.

2. until the room had become a beautiful bower. The child’s bedroom turning into a place where things grow will be familiar to readers of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Golden Flower Pot, which also influenced Andersen’s “The Goblin and the Grocer,” similarly describes a writing studio turning into an outdoor landscape. From Hoffmann (one of the three writers whom Andersen acknowledged as the most important influences on his writing—the other two were Sir Walter Scott and Heinrich Heine), Andersen learned how to build the transition from the ordinary to the extraordinary, finding poetry and magic in everyday objects and in the diminutive mode.

3. No one has ever seen anything like it! With a few deft strokes the narrator manages to evoke a vivid new world and coax it into being. Moving from the visual (“prettier than a rose”) to the olfactory (“with a fragrance so sweet”) to the gustatory (“if you tasted it”), he not only “spruces things up” but creates beauty that is drenched in light (“the fruit gleamed like gold”) and full of savory delights (“buns filled with currants”).

4. over in the drawer where Hjalmar kept his schoolbooks. The imaginative and fantastic are often shadowed by the instructive and pedagogical in Andersen’s stories for children. Just when Hjalmar seems to be set free for the pleasures of storytelling and dreaming, the slate and the copybook demand attention and turn the volume up so high that they cannot be ignored. Andersen saw deep conflicts between education and imagination, and he mourned how schooling banishes enchantment from the child’s world: “As long as the little one has never been further than Copenhagen, and their grandmother or nurse has filled their heads with enchanted princes and princesses, with mountains of gold and talking birds, the little heads will dream about this fantasy land and will look over the sea which meets the sky between the Danish and Swedish coasts. That’s where it must be, they think, as they paint a picture of the lovely new world, but they grow older and go to school, and this immediately destroys the fantasy land, because they learn that beyond the water lies Prussia and all of Germany” (Travels, 289).

5. until they were just as elegant and straight as their models. Beautiful handwriting is important for Andersen, and he makes a point of emphasizing the capabilities of the artist student in “The Goblin and the Grocer.” Ole Shut-Eye has the power to transform Hjalmar’s handwriting, but only for the duration of his stay. The magic loses its effect with the dawning of a new day.

6. every piece began chattering. In “The Goblin and the Grocer,” the supernatural creature in the title also has the ability to endow objects with the power to speak. He does so by placing a human tongue on pieces of furniture and other objects.

7. Ole Shut-Eye used his magic spray on the painting. The landscape described in the painting is one that appears frequently in Andersen’s works, most notably in “The Ugly Duckling” and “The Nightingale.” A forest, a lake, a castle, and flowers seem to be the primary features in many of the nature scenes, and Andersen did not hesitate to repeat those elements with little variation. Just as Hjalmar’s room can transform itself into an outdoor scene, so too the painting can come to life, allowing Hjalmar to enter its domain and to travel on a boat down its river through forests and towns. The painting as portal to a wonder world functions like the books and mirrors of many fantasy worlds, for example Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

8. the trees were telling tales about robbers and witches. Hjalmar enters a world that contains many allusions to other tales by Andersen. The description of the landscape echoes that of other tales, but there are also swans with golden crowns (“The Wild Swans” and “The Ugly Duckling”), tales about robbers and witches that recall “The Snow Queen,” and flowers, elves, and butterflies that indulge in activities reminiscent of what goes on in “Thumbelina.”

9. the woman who had looked after him when he was a small boy. In meeting up with his nanny, Hjalmar seems to be regressing, moving back into the past rather than maturing and moving forward. But like Gerda and Thumbelina, he is drawn into a world of light, beauty, and poetry, thereby developing an artistic sensibility that runs counter to what he learns in school.

10. There he was on the deck. Like the swallow in Thumbelina, this stork is unable to keep up with the others and collapses from exhaustion. Thumbelina revives the swallow through her tender ministrations, unlike Hjalmar, who is both kind in liberating the stork from the henhouse and aggressive in threatening to use the turkey for the next day’s dinner.

11. asked the stork who he was. The cruelty of the barnyard is well known from “The Ugly Duckling,” which shows the newly hatched bird attacked as a misfit by the other animals.

12. he was thanking Hjalmar by nodding in his direction. The motif of the grateful animal is found in the folklore of many cultures. “The White Snake” and “The Queen Bee” in the Grimms’ collection show the hero benefiting from interventions to protect the safety of animals. The hero’s humility and suitability for a rise in rank are often demonstrated through his willingness to assist those who are lower in social station (beggars), less strong (old men and women), and lower on the food chain. Hjalmar’s willingness to liberate the stork from the taunts of the other animals demonstrates his kindness and maturity, but at the same time it does not signify pure benevolence, for Hjalmar is not at all loath to contemplate the slaughter of the turkey for tomorrow’s soup.

13. the boy became smaller and smaller. Magical shrinking and growth are associated most frequently with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, but Andersen took advantage of miniaturization, not only here but in the tale of Thumbelina. Tom Thumb is the most famous of all diminutive fairytale figures, but he and Thumbelina, unlike Hjalmar, are small to begin with.

14. “you will be able to wear the tin soldier’s uniform.” Hjalmar, like the steadfast tin soldier in the story of that title, goes out into the wide world to find adventure. He is whisked off to the wedding but, as a living boy rather than as a tin soldier, retains control over his actions.

15. touchwood. A type of wood that readily ignites and also a form of tinder made from a species of fungus.

16. “Shall we go to the country, or would you rather travel abroad?” The bridegroom’s innocent question provokes a deep debate about the virtues of home versus abroad. The swallow, a migratory bird that flies to warmer climes in the winter, trumpets the beauty of southern regions, while the hen insistently defends the pleasures of home. A defining paradox of Andersen’s life, according to one critic, was “traveling with border- and boundary-crossing desires through a life filled with borders and boundaries” (Houe 1999, 95).

17. “And we don’t have robbers.” The risks associated with travel were high in Andersen’s time, and the travel diaries provide a clear sense of the dangers facing tourists. On the one hand, Andersen saw travel as “invigorating, a cleansing of the soul.” “I need this refreshing bath which seems to make me both younger and stronger when I return home.” In his travels to Turkey and Greece, Andersen documented some of the risks he was facing. He writes about a “recent uprising in the Balkans—where it was said thousands of Christians had been murdered.” Yet Andersen was undaunted: “I am not among the bravest, a fact that has often been pointed out to me. . . . However, I must explain that while lesser dangers disturb me, when an adventure presents itself I forget my fearful anticipations, and, even if I am still trembling, I meet this perhaps even more dangerous situation with equanimity” (Travels, 166–67). Disease (outbreaks of cholera required quarantine), bandits, political uprisings, storms at sea were just a few of the “adventures” awaiting Andersen on his travels.

18. “We must have the whole world spruced up.” Ole Shut-Eye, for all his associations with whimsy and imagination, also tidies up and keeps order in the domestic sphere, as in celestial regions. Combining flights of fancy with good etiquette, he is a puckish pedagogue for Hjalmar.

19. “darning needle who gave herself such airs.” Andersen’s tale “The Darning Needle” begins, “There was once a darning needle, who thought herself so fine, she imagined she was a sewing needle.” The proud darning needle bears a close resemblance to the steadfast tin soldier and experiences many of the same adventures, traveling and sailing, until she is run over by a wagon: “She lay there, stretched out full length, and there she may lie still.”

20. “introduce you to my own brother.” The Greek Hypnos (his Roman counterpart is Somnus) personifies sleep and was represented as a brother of Death (Thanatos) and a son of Night (Nyx). In many ancient works of art, Sleep and Death are represented as two youths slumbering or holding torches turned upside down. Andersen here evokes an association that is already powerfully present in the minds of children—the fear that falling asleep and losing consciousness is akin to dying. “If I should die before I wake” (a common nighttime prayer in the Western world) reinforces the anxiety that you might fall asleep and never wake up.

21. hear a beautiful story. The distinction between those with “good” cards and those with “mediocre” or “poor” cards repeats the distinction made at the beginning of the tale between good children and naughty children.