Skyggen

Andersen wrote much of “The Shadow” in 1846 when he was in Naples. In a diary entry of June 8, he complained: “The heat is pouring down. I hardly dare go outside.” The following day, he announced: “In the evening, began writing the story of my shadow.” Note the use of the possessive pronoun, with Andersen cast as the “learned man” from “cold lands” so that “The Shadow” becomes a reflection—or shadow—of its author. The tale marks a real turning point in Andersen’s literary production, for it establishes him as an author whose work is animated by the theme of artistic and existential crisis. Like his British, European, and American contemporaries, he became fascinated with doubles, shadows, portraits, and statues, finding in them metaphors for exploring the divided self.

The autonomous shadow has appeared in many nineteenth-century literary works, most notably Adelbert Chamisso’s The Marvelous Story of Peter Schlemihl (1814), which was translated into many languages shortly after its publication. Andersen met Chamisso when he traveled to Berlin in 1831 and noted in his autobiography that he had found in the Prussian poet of French descent a “life-long” friend. Andersen deepens Chamisso’s story by turning the shadow into the sinister force of the tale, suggesting that truly menacing forces emerge from within.

In the hot countries the sun can really scorch you!2 People can turn as brown as mahogany, and in the hottest countries they can be baked black. One day, a learned man traveled from the cold countries to one of the moderately hot countries. He was sure that he would be able to go about his business just as he had back home, but he soon discovered otherwise. Along with all other sensible souls, he had to stay indoors.3 All day long, the shutters were drawn and the doors were kept closed. It looked just as if everyone was still sleeping or not at home. The narrow street on which the man lived was lined with tall buildings and was laid out so that it was flooded with sunshine from morning until evening. It was really unbearable!4 The learned man from the cold countries—he was a young man, a clever man—felt just as if he were sitting inside a blazing hot oven. It wore him out. He grew quite thin, and even his shadow began to shrink until it was much smaller than it had been at home. The sun took its toll on it as well. Not until the evening, after sundown, did the man and his shadow come back to life.5

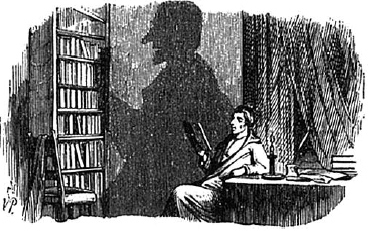

VILHELM PEDERSEN

The learned man is already overshadowed by his shadow as he reads at his desk. The illustration captures the drama that will unfold between the man and his shadow in a closed, claustrophobic space.

It was a real pleasure to watch that happen! As soon as a candle was brought into the room, the shadow would stretch itself out all the way up the wall and would even reach the ceiling, it made itself so long. It had to stretch out like that to get its strength back. The learned man went out on the balcony to stretch, and, as soon as stars appeared in the lovely, clear sky, he also seemed to come back to life.

People appeared on all the balconies up and down the street—and in the warm countries every window has a balcony—because you have to breathe fresh air, even if you are used to being mahogany colored. Things grew quite lively, upstairs and down. Cobblers and tailors and everyone else moved out into the street. Tables appeared, then chairs, and candles were lit—there were over a thousand candles burning. One person would be talking, while another sang. People strolled down the street, carriages drove by, and donkeys trotted along, with their bells sounding ding-a-ling-ling. Hymns were sung as the dead were buried; urchins set off firecrackers; and church bells were ringing. Oh yes, it was very lively down in that street.6

Only one house stayed quiet7—the one directly across from where the learned man was living. Someone must have been living there, because there were flowers growing on the balcony. They were thriving, even under a hot sun, and how could they unless there was a person there to water them? Someone had to be watering them, and so there must be people living in the house. As it turns out, the door across the way was left ajar every evening, but it was completely dark inside, at least in the front room. From somewhere farther back in the house you could hear the sound of music. The learned stranger thought the music was quite fabulous, but it is possible that he was just imagining all this, for he thought that everything in the warm countries was really marvelous, except for the sun. The stranger’s landlord said that he had no idea who was renting the house across the street. No one seemed to be living there, and, as for the music, he found it terribly dreary: “It sounds as if someone is practicing a piece that is beyond him—always the exact same piece. ‘I’ll get it right one of these days,’ he probably tells himself, but he just never does, no matter how hard he tries.”

The stranger woke up once in the middle of the night. He was sleeping right near the open balcony door, and when a breeze lifted the curtain, he thought he saw a strange, shimmering light on his neighbor’s balcony.8 The flowers were glowing like flames in the most beautiful colors. Right in the middle of the flowers stood a slender, enchanting maiden, and she seemed to be glowing too. The brightness hurt his eyes, but that was because he had just woken up and opened them too wide after rousing himself so suddenly. Then he jumped out of bed and, without making a sound, peered through the curtains, but the maiden had vanished and so had the light. The flowers were no longer in flames and looked just fine, as they always did. The door was ajar, and from far inside came the sound of music so lovely and soothing that you could lose yourself in sweet thoughts. It was enchanting. But who was living there? Where was the real entrance? The entire ground floor was nothing but shops, and people couldn’t constantly be walking through them.

One evening the stranger was sitting out on his balcony. In the room behind him a candle was burning, and so it was quite natural that his shadow appeared over on the wall across the way. Yes, it appeared right there with the flowers on the balcony. And whenever the stranger moved, the shadow moved too, for that is what shadows do.

“I think my shadow is the only living thing you can see over there,” the learned man thought to himself. “Look how much at home it is among the flowers. The door is wide open. If only my shadow were clever enough to step inside,9 have a look around, and come back to tell me what it had seen.”

“Yes, you would be doing me a real service,” he said jokingly. “Kindly step inside. Aren’t you going in?” He nodded to the shadow, and the shadow nodded back at him. “Run along now, but don’t get lost!”

The stranger rose, and his shadow on the opposite balcony got up with him. The stranger turned, and his shadow turned as well. If anyone had been paying attention, they would have seen the shadow enter the half-open balcony door in the house across the street at the very instant when the stranger returned to his room, letting the drapes fall behind him.

The next morning the learned man went out to drink his coffee and read the newspapers. “What’s this?” he said, as he stepped out into the sunlight. “My shadow is gone! So it actually did leave me last night, and it hasn’t come back. That’s really irritating.”

What annoyed him most was not so much the loss of his shadow as the fact that there was already a story about a man without a shadow.10 Everyone back home in the cold countries knew that story. If he returned home and told them his own story, they would just say that he was copying the other one and shouldn’t bother going on. So he decided to say nothing at all about it, and that was certainly the sensible thing to do.

That evening he went back out on the balcony. He put a candle directly behind him, because he knew that shadows always like to use their masters as a screen, but he could not entice it to come back. He made himself short, and he made himself tall, but there was just no shadow. It refused to show up. “Ahem, ahem!” he repeated, but it was no use.

This was all very annoying, but in the hot countries everything grows quite rapidly, and in a week or so he noticed to his great satisfaction that a new shadow had started growing11 at his feet whenever he went out into the sunlight. The root must have been left behind. Within three weeks he had a decent enough shadow, which, when he set out to go back north, grew longer and longer until it became so long and broad that half of it would have been quite enough.

The learned man returned home. He wrote books about what was true in the world and what was good and what was beautiful. Days turned into years, and many years went by. Then one evening he was sitting in his parlor and heard a faint knock at the door.

“Come in,” he said, but no one did. He opened the door and there before him stood a man so extraordinarily thin that it gave him an eerie sensation. The caller was, by the way, dressed faultlessly and was no doubt a distinguished fellow.

“With whom do I have the honor of speaking?” the learned man asked.

“Oh,” the distinguished visitor said. “I had a feeling you wouldn’t recognize me now that I’ve put some flesh on my body and have some clothes on. You probably never expected to see me in such fine shape. Can’t you tell that I’m your former shadow? You probably didn’t think I would ever show up again. Everything has gone exceptionally well for me since I last saw you. I’ve become a wealthy man in every way, and, if I have to buy my freedom, I can.” With that, he rattled a bunch of valuable seals hanging from his watch and began to stroke a massive gold chain around his neck. His fingers seemed to glitter from all the diamond rings on them. And the jewelry was all real.

“I can’t get over it!”12 the learned man said. “What can this all mean?”

“It’s definitely not something you see every day,” the shadow said. “But then you’re also no ordinary man, and, as you know, I’ve been following in your footsteps since childhood.13 As soon as you thought I was mature enough to go out into the world on my own, I went my way. And now I find myself in splendid circumstances, but a strange longing to see you one last time before you die overcame me. You are going to die, you know! I always wanted to return to this region, because we all love our homeland. I know that you have a new shadow. Do I owe you—or it—anything?14 Please let me know if I do.”

“Is it really you?” asked the learned man. “This is highly unusual. I would never have imagined a shadow could return as a human being.”

“Just let me know what I owe,” the shadow said, “because I don’t want to be in anyone’s debt.”

“How can you talk like that?” the learned man said. “What kind of debt are we talking about? You’re as free as anyone else. I’m just delighted to learn of your good fortune. Sit down, old friend, and tell me how all this came about and what you saw in the house across the street in the hot country.”

“I’ll tell you all about it,” the shadow said, sitting down. “But you must promise me that if we run into each other in town, you won’t tell a soul that I was once your shadow. I’m considering getting engaged, and I’m wealthy enough to support more than one family.”

“Don’t worry,” the learned man said. “I won’t tell anyone who you really are. Let’s shake on it. I promise, and a man is as good as his word.”15

“And a word is as good as its—shadow,” the shadow replied, for that was the only thing it could say.

It was really quite remarkable how human the shadow had become. It was dressed in black,16 with clothes made from the finest cloth, and it was wearing patent-leather shoes along with a top hat that could be pressed perfectly flat until only brim and top remained, not to mention what we have already seen—those seals, the gold chain, and the diamond rings. Yes, indeed, the shadow was exceptionally well dressed, and that’s just why it appeared to be so human.

“Well, let me tell you!” the shadow said, stepping down as hard as it could with those new patent-leather shoes on the sleeve of the learned man’s new shadow, which lay like a poodle at his feet. Maybe this was arrogance, but maybe it was just trying to make the new shadow stick to his own feet. The shadow on the floor didn’t move or make a sound.17 It was no doubt listening carefully so that it could learn how to win its freedom and someday become its own master.

“Do you know who was living in the house across the street?” the shadow said. “She was the most beautiful of all creatures—Poetry herself. I was there for three weeks, and I might as well have been there for three thousand years, reading everything that has ever been written. That’s what I’m telling you, and it’s the truth. I’ve seen everything, and I know everything.”

“Poetry!”18 the learned man cried. “Oh, yes, yes—she often keeps to herself in the big cities. Poetry! Yes, I saw her myself, for one brief moment, but my eyes were heavy with sleep. She was standing on the balcony, as radiant as the Northern lights. Tell me more! Tell me more! You were up on the balcony. You went through the door, and then—”

“And then I was standing in the antechamber,” the shadow said. “You used to stare into that room all the time from across the street. There were no candles in there, and the room was in a kind of twilight. But one door after another stood open in a long row of brilliantly lit halls and rooms. The blaze of lights would have killed me if I had gone all the way into the room where the maiden was. I was level-headed and took my time—that’s what you have to do under those circumstances.”

“And what did you see?” the learned man asked.

“I saw everything, and I’ll tell you all about it. But—and I’m not saying this to be arrogant—if you take into account that I’m a free man with considerable talents, not to mention my social position and my considerable fortune, it makes sense for you to address me in a more formal manner,19 and I would be grateful for the courtesy.”

“I beg your pardon, Sir!” the learned man said. “I’m just falling back into an old habit that is hard to change. You’re perfectly right, and I’ll be more careful now. But now, sir, tell me about everything that you saw.”

“Everything!” the shadow said. “You realize, then, that I saw everything and that I know everything.”

“What did it look like all the way back?” the learned man asked. “Was it like a green forest?20 Was it like a holy temple? Was it like the starry skies when you stand high up on a mountain?”

“Everything was there,” the shadow said. “I didn’t go all the way inside, as you know. I stayed in that antechamber in the twilight, but that was the perfect place to be. I saw everything, and I know everything. I have been in the antechamber of Poetry’s court.”

“But what did you see? Did the ancient gods march through the halls? Were the heroes of times past fighting there? Were sweet children playing there and talking about their dreams?”

“I’m telling you, I was there, and you have to realize that I saw everything there was to see. Had you come over there, it would not have made a man of you, but it did make a man of me. I learned to understand my innermost nature, what I was born with, and my connection with Poetry.21 Yes, back when I was living with you, I never thought at all about such matters. But you must remember how astonishingly large I became at sunrise and sunset. And the moonlight made me almost more visible than you. I didn’t understand myself at the time, but in that antechamber, I came to know my true nature. I became a man and returned completely transformed. But you were no longer in the hot regions. Being a man, I was ashamed to be seen as I was. I needed boots, clothing, and all the surface polish that makes a person recognizable.

“I went into hiding—and I’m going to tell you this because I know you won’t put it in a book22—under the skirts of the woman who sells cakes. That woman had no idea how much she was concealing. I didn’t venture out until evening, and then I ran through the streets in the moonlight and stretched myself tall against the walls. It really tickled my back. I ran up and down the streets,23 taking peeks into the highest windows, into parlors and into garrets. I looked in where no one else could look. I saw what no one else could, or should, see.24 If truth be told, it’s a nasty world. I wouldn’t even want to be human except that everyone seems to think that it’s so grand. I saw the most unthinkable things going on between men and women, and between parents and their perfectly darling children.”

“I saw,” the shadow continued, “what nobody knows but what everyone would like to know, the scandalous behavior next door. If I had written a newspaper, everyone would have been reading it! Instead I just wrote to the people directly involved, and everywhere I went there was a huge uproar. They were terrified of me, but they also became terribly fond of me. The professors appointed me a professor, and the tailors made me new clothes—in fact, my wardrobe is almost complete. The master of the mint coined new money for me, and women told me that I was quite handsome. And so I became the man I am now. For now I must bid you farewell. Here’s my card. I live on the sunny side of the street, and I am always at home when it rains.” And off he went.

“That was really strange,” the learned man said.

Days and years passed, and the shadow called again. “How are you doing?” he asked.

“Not so well, I’m afraid,” the learned man said. “I’m still writing about the good, the true, and the beautiful,25 but no one wants to hear about such things. I’m in utter despair, because I take it all personally.”

“Well, I don’t,” said the shadow. “I’m putting on weight, and that’s what we all should try to do. You don’t understand the ways of the world, and that’s why your health is suffering. You really have to get away. I’m taking a trip this summer. Would you like to join me? I’d enjoy having a traveling companion. Will you come along as my shadow? It would be such a pleasure to have you accompany me, and I’ll even pay all the expenses.”

“That’s going too far,” the learned man said.

“It all depends on how you look at it,” said the shadow. “It would do you a world of good to travel. If you promise to be my shadow, the trip won’t cost you a thing.”

“This has gone far enough!” the learned man declared.

“But that’s how the world is,” the shadow told him. “And that’s how it will always be.” And off he went.

Things were not going well at all for the learned man. Misfortune and all kinds of trouble plagued him, and what he had to say about the good, the true, and the beautiful was as appealing to most people as roses are to a cow. In the end, he became quite ill.

“You look like a shadow of yourself,” people said to him, and the learned man would tremble because it made him stop to think.

“You really have to spend some time at a spa,” the shadow told him when he came for a return visit. “It isn’t really a matter of choice. I’ll take you with me for old times’ sake. I’ll pay for the trip, and you can write up an account and do your best to amuse me along the way. I need some time at a spa as well, for my whiskers are just not growing out the way they should be. That’s a trial as well, because you can’t get along without a beard. Come now, be reasonable and accept my proposal. We’ll travel together, just like friends!”

And off they went. The shadow was now the master, and the master was the shadow.26 They drove together; they rode together; they walked together, side by side, in front or in back, depending on where the sun stood in the sky. The shadow made sure that it always took the lead, and the learned man himself didn’t spend much time thinking about it, for he was a kindhearted person, exceedingly amiable and gentle. One day he said to the shadow: “Now that we have become traveling companions and because we have been together since childhood, shouldn’t we call each other by our first names? That would be much more agreeable.”

“You have a point there,” said the shadow, who was now the true master. “What you say is very candid and tactful, and so I will be equally candid and tactful with you. As a learned man, you are perfectly well aware of how strange human nature can be. Some people cannot bear to touch gray paper—it makes them feel queasy. Others recoil when they hear the sound of a nail scraping against a windowpane. As for me, I have a queasy sensation when I imagine you calling me by my first name. I feel pressed down to the ground just as I was in my former position with you. As you can see, it’s just a feeling—it has nothing at all to do with arrogance. I just can’t let you call me by my first name. But I’m entirely happy to meet you halfway and to call you by yours.”27 And from then on, the shadow called his former master by his first name.

“This has really gone too far,” the learned man thought. “Now I’m calling him by his last name and he is using my first name.” But he had to put up with it.

They arrived at last at the spa, where there were many people from foreign lands, among them a beautiful princess. She was suffering from the disease of being able to see too well,28 and that can be highly distressing. She noticed right away that the newcomer was a very different sort of person from all the rest. “They say he is spending time here so that his beard will grow. But the real reason is obvious to me. He can’t cast a shadow.”

Once her curiosity was aroused, the princess went out for a stroll and struck up a conversation with the stranger. As the daughter of a king, she could come right to the point, and so she said, “Your problem is that you can’t cast a shadow.”

“Your Royal Highness must have improved considerably!” the shadow replied. “I know that you suffer from seeing things far too clearly. But you are getting over it, and I see that you are just about cured. As a matter of fact, I have a most unusual shadow. Do you see that fellow who is always by my side? Other people have ordinary shadows, but I’m not fond of the ordinary. Some people give their servants finer livery than they themselves wear. In that spirit, I’ve dressed up my shadow as a man. As you can see, I’ve even outfitted him with a shadow of his own. Yes, it’s very expensive, but it’s worth it to have something unique.”

“What?” the Princess thought to herself. “Can it be true that I’ve recovered? This is the best spa anywhere, and these days the waters are said to have wonderful medicinal powers. But I’m not planning on leaving now, because this place is just starting to become interesting. I’ve taken a liking to that stranger. I just hope that his beard doesn’t start to grow, because then he’ll leave.”

That evening, the princess and the shadow danced in the grand ballroom. She was light on her feet, but he was even lighter.29 She had never danced with a partner like that. She told him the name of the country she was from, and he knew it well. He had spent some time there, but while she had been away. He had peeked in every window, high and low. He had seen this, and he had seen that. And so he found it easy to talk with the princess and to make references that astonished her. She was convinced that he had to be the wisest man on earth. His knowledge impressed her deeply, and, when they started dancing again, she fell in love with him. The shadow was aware of this, for she was practically looking right through him. Then they danced again, and she came very close to telling him, but she hesitated. She really had to consider her country and her throne, as well as all the people she would rule in her kingdom.

“He’s a wise man,” she said to herself. “And that’s all to the good. He’s a superb dancer, and that’s also good. But I wonder if he has a deep knowledge of things—that’s just as important. I’ll have to test him.” She began asking more difficult questions, questions she herself could never have answered. The shadow gave her a strange look.

“You can’t answer my questions?” asked the king’s daughter.

“They are mere child’s play,” said the shadow. “Even my shadow over there by the door could answer those questions.”

“Your shadow!” said the princess. “That would be quite remarkable.”

“I’m not saying for certain,” the shadow said. “But I believe he can, because he has been following me around all these years and paying attention. Yes, I’m inclined to think he can. But if Your Royal Highness will permit, I must explain that he is so proud of being able to pass for human that, if you want to put him in a good mood—and he will have to be in a good mood in order to answer properly—you will have to treat him as if he were a regular human being.”

“That’s fine with me!” the princess replied.

And so she walked over to the learned man, who was standing in the doorway. She talked with him about the sun and the moon, and about people, what they are like on the inside as well as on the outside. He answered her wisely and well.

“What a man he must be to have such a wise shadow!”30 she thought. “What a blessing it would be for my people and for my kingdom if I were to marry him. And that’s just what I’m going to do.”

The princess and the shadow soon came to an understanding, but no one was to know anything until after she had returned to her kingdom.

“No one. Not even my shadow!” the shadow said. And he had his reasons for saying that.

They arrived at last in the country where the princess ruled when she was at home.

“Listen, my good friend,” the shadow said to the learned man. “Now that I am as happy and powerful as anyone can be, I’d like to do something special for you. You can live with me in the castle, drive around with me in the royal carriage, and make a hundred thousand a year. But in return you will have to let everyone call you a shadow, and you can never claim that you were once a human being. Once a year, when I’m sitting on the balcony in the sunshine, you must lie at my feet as shadows do. I am planning on marrying the king’s daughter, and the wedding is to take place tonight.”

“No! That’s going too far,” said the learned man. “I refuse. I refuse to do it! That would mean betraying the entire country and the princess as well. I’m going to tell everyone the whole story31—that I’m the man and that you are just a shadow dressed up like a man.”

“No one will believe you,” the shadow said. “Be reasonable, or I’ll call the guards.”

“I’m going straight to the princess,” the learned man said.

“But I’ll get there before you,” said the shadow. “And you are going to jail.” And that’s exactly where he went, because the guards decided to obey the man who was going to marry the princess.

“You’re trembling,” the princess said, when the shadow came into her room. “Has something happened? You mustn’t get ill on the night that we are going to be married.”

“I have just been through the most dreadful experience you can imagine!” said the shadow. “Just think! Well, I suppose a poor shadow’s brain can’t take very much. But imagine! My shadow has gone mad. He thinks that he is a human, and—picture this—he takes me for his shadow.”

“That’s horrifying!” said the princess. “He’s locked up, isn’t he?”

“Oh, of course. But I doubt he will ever recover.”

“Poor shadow,” said the princess. “He must be terribly unhappy. It would be an act of compassion to liberate him from the little bit of life left in him. If I stop to think about it, there’s no choice but to do away with him—very quietly.” “How painful that is,” the shadow said. “He was such a loyal servant.” And he managed to let out what sounded like a sigh.

“What a noble character you have,” the princess declared.

VILHELM PEDERSEN

The shadow and the princess appear on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowds at their wedding ceremony.

That evening the entire city was brightly lit. The cannons boomed, and the soldiers presented their arms. It was quite a wedding!32 The princess and the shadow appeared on the balcony to be admired by all, and they received another round of cheers.

The learned man didn’t hear any of that, for by then they had taken his life.33

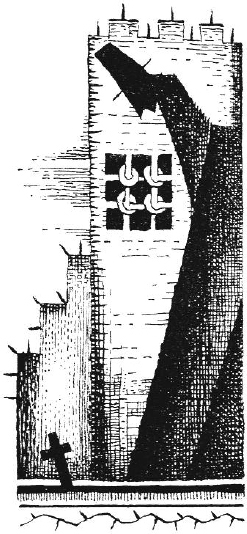

KAY NIELSEN

The shadow itself (or the shadow of the shadow), in silhouette against the prison, gazes down at the cross marking what is presumably the gravesite of the learned man.

1. Shadow. Edgar Allan Poe’s “Shadow: A Parable” (1850), Oscar Wilde’s “The Fisherman and His Soul” (1891), J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904), and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s The Woman without a Shadow (1919) are all about what it means to lose a shadow. Often seen in symbolic terms as a manifestation of the soul (“the shadow of the body is the body of the Soul,” Wilde tells us in his story), the shadow can also function as an uncanny double that detaches itself from the body to haunt others. The shadow becomes a spectral presence that generally incarnates the darker desires and longings of the self. The Danish term for shadow, skygge, can mean both shade (in the sense of a ghost or a spirit) and shadow.

2. the sun can really scorch you. The opening sentences, in Andersen’s signature casual, conversational tone, make light of what will become a weighty matter. The scholar has entered a domain in which your skin color can change (note that the implied reader has white skin) to brown or black. Instead of risking that particular metamorphosis, in which he could be “baked black,” the scholar takes up residence in a “moderately hot” country and avoids heat and light, retreating into his study to investigate the good, the true, and the beautiful (thereby remaining “white”). Ironically, his “black” side nonetheless emerges in the form of a shadow that achieves dominance.

The menacing shadow has dark habits. In his first appearance as a man, he is “dressed in black, with clothes made from the finest cloth,” with a black hat. But his transformation is achieved through exposure to the “brightness” of the apartment that is described as the dwelling place of Poetry. And he begins to sport accessories that are generally associated with the sparkle and shimmer of art. The sharp distinctions between black and white established at the beginning of the story through skin color begin to break down in both moral and aesthetic terms.

3. Along with all other sensible souls, he had to stay indoors. The use of the term “sensible,” along with the description of the learned man as a scholar dedicated to the life of the mind, suggests that the warmer countries lack the intellectual power found in northern regions. Yet the term “sensible” may also be used ironically, as it is when the narrator notes that the learned man decides not to write about himself, “which was very sensible of him.”

4. It was really unbearable! The living conditions are unbearable in part because of the heat and in part because of the claustrophobic living conditions. Shutters and doors close the learned man off from the world, and his contact with the outside world seems limited to the nocturnal outings on the balcony, where he appears as an observer rather than as a participant, looking onto a narrow street with tall buildings. It is precisely by shutting himself off from the world and retreating from life that the learned man creates the conditions for the separation of shadow from self. On his own trips to Italy, Andersen rarely closeted himself in and spent much of his time visiting sights, meeting literary worthies, and socializing with his fellow travelers. In his diaries, he describes the effects of the sun during a stay in Naples: “The heat from the sun followed us, becoming more and more oppressive as the sirocco blew hot and dry air; I thought as a Northerner that the heat would do me good. I should have noticed that the Neapolitans stayed at home, or crept along in the shadow of the houses, as Paar and I dashed from one museum to the next or down to the pier. Then, one day, my breathing started to fail, the sun burnt into my eyes, the rays going through my head and back, and I fainted dead away” (Travels, 257).

5. did the man and his shadow come back to life. Even at this early point in the story, the shadow has been anthropomorphized with its own identity and agency. It seems to shrink, stretch, and become animated on its own.

6. it was very lively down in that street. The effervescent quality of everyday life forms a sharp contrast to the quiet, hermetic existence in which scholar and shadow dwell and to the silence of the building in which Poetry dwells. The scholar, while aware of the life below, finds himself attracted more powerfully to the mysterious, silent abode. Andersen, like many writers, found himself divided between the lively attractions of the real world and the beauty of an imaginative, inner world. The learned man, however, seems to reside in a limbo, not daring to engage with one or the other.

7. Only one house stayed quiet. The beauty of the flowers is the most compelling attraction of the building across from the scholar. The “fabulous” music breaks the silence of the front rooms and deepens the aura of mysterious beauty in the architectural wonder situated in the urban landscape.

8. a strange, shimmering light on his neighbor’s balcony. It is not clear whether the enchanting maiden is dream or reality. The stranger thinks he sees a peculiar glow and is then persuaded that the flowers are indeed gleaming like flames, but when he opens his eyes and rouses himself “from sleep,” the vision of flowers in flames and of the maiden vanishes. The vision produces uncertainty in the mind of the character and the reader. That uncertainty is symptomatic of an effect that the literary critic Tzvetan Todorov has called “the fantastic,” as opposed to “the marvelous,” which is truly supernatural, or “the uncanny,” which is strange but not contrary to natural laws. The fantastic is the hallmark of the poetic fairy tales written by E.T.A. Hoffmann, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Adelbert von Chamisso, and the other German Romantics who inspired this particular story.

9. “If only my shadow were clever enough to step inside.” “No sooner said than done” takes on a new depth of meaning here. The learned man speaks words that work magic, for his wish is quickly—and subtly—translated into reality. He has, in a sense, willed his shadow to detach itself from him, commanding it to do what he is afraid to do. At first the shadow’s moves are in concert with its owner (“the shadow moved too”), then the shadow appears to have an independent existence (“Look how much at home it is among the flowers”), and finally it actually walks in the opposite direction, entering the building across the way. Note the absence of witnesses (“If anyone had been paying attention”), a fact that emphasizes the possibility that the learned man is hallucinating.

10. a story about a man without a shadow. The story that everyone in the “cold countries” knows about is most likely Adelbert von Chamisso’s The Marvelous Story of Peter Schlemihl. Chamisso’s story of a man who sells his shadow to the devil became so well known that it was cited in works by E.T.A. Hoffmann (“Adventures on a New Year’s Eve,” written in the year Peter Schlemihl was published) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (“The Intelligence Office” of 1844). Note the anxiety of influence expressed in the scholar’s fear that others will believe that he is simply copying another author and creating a shadow of another story. That shadow of the story of Peter Schlemihl does exactly what the shadow of the learned man does: disappear only to reappear in an unexpected new form. In Andersen’s tale, the shadow detaches itself from the scholar to lead a successful, independent life.

11. a new shadow had started growing. The growth of a new shadow points to the possibility that the learned man is simply hallucinating, but it may also function as an event that reinforces the supernatural turn to the story once the shadow detaches itself.

12. “I can’t get over it!” The literal meaning of the learned man’s words are “I can’t come to my self!” It is at this point that the text, as Clayton Koelb points out, acts out a literal meaning that is ordinarily impossible. “That ‘I’ should meet ‘myself’ is a simple matter for language,” he observes, “but we do not expect that grammatical possibility to be thus transformed into practice” (Koelb, 207).

13. “I’ve been following in your footsteps since childhood.” The playful rhetoric in the midst of existential crisis is characteristic of the tale’s style, and here the shadow plays on the figurative and literal dimensions of language, revealing how he has, for most of his life, taken after the scholar.

14. “Do I owe you—or it—anything?” Note how the shadow here, in acknowledging the new shadow as “it,” also validates the division of self and shadow even as he sets up a hierarchy that privileges the learned man (“you”) over his shadow (“it”). The shadow seems to have the success in commerce that the learned man himself never achieved.

KAY NIELSEN

The shadow appears at the home of the learned man. He is dressed in black and carries in one hand the flat top hat and wears diamond rings, along with a watch on a chain. Confident and debonair, he cuts a dashing figure on the moonlit evening.

15. “a man is as good as his word.” In this key dialogue between the man and his shadow, the learned man asserts that a man is his word and his shadow declares that a word is his shadow. Both man and shadow have the word in common, and, in this rhetorical sleight-of-hand, it becomes evident that, through language, man and shadow can reverse their positions, as they do in Andersen’s narrative. As soon as shadow and learned man take these oaths, the shadow begins to take over the life of the man.

16. It was dressed in black. The shadow, appropriately, wears clothing that reflects his true identity, including a hat that can be closed so that only the crown and brim (for which the Danish word is “shadow”) remain. At the same time, he wears brilliant, costly jewelry—gold and diamonds that point to his wealth and to the fact that he has, at least in part, transcended his dark existence and affiliated himself with the bright light of art, even if in its vulgar, material manifestation.

17. didn’t move or make a sound. The second shadow, which has grown as a replacement for the first, seems also to have human qualities. Note that the first shadow contemplates the possibility of obtaining the scholar’s second shadow, perhaps to facilitate his full transformation into a man. Unlike the learned man, the shadow has “a root” and can continue to grow new copies of itself.

18. “Poetry!” The learned man had perceived the building across the way as an enchanted world (en Trolddom), and he discovers, retrospectively, that the maiden he saw was Poetry, a figure who appears at nighttime, but with a brightness rivaling that of the sun, “as radiant as the Northern lights.” Like the sun, the maiden creates a lethal abundance of light, enough to have “killed” the shadow, who cannot tolerate too much brightness, given his dark nature (shades of the mole in “Thumbelina”). The encounter between the dark shadow and the bright spirit of Poetry allegedly leads to knowledge (“I’ve seen everything, and I know everything”) and also gives flesh to the shadow, but, ironically, it appears to have turned him into a cynical, sinister figure who uses his shadowy abilities to intimidate others, betray the learned man, and dupe the princess.

19. “address me in a more formal manner.” In Danish, as in French and many other languages, a distinction is made between the formal “you” (De) and the familiar “you” (Du). During their first encounter, the man uses the familiar Du, and the shadow speaks with the man using De until finally insisting on also being addressed with De. Andersen himself had been deeply humiliated when his offer to Edvard Collin (the son of his benefactor) to shift to the Du form of address was rejected. On May 28, 1831, Collin wrote to him: “There is something that I simply can’t explain in my reaction. . . . When someone I’ve known for a long time—a person I admire and like—invites me to use Du, I develop a mysteriously unpleasant reaction.”

20. “Was it like a green forest?” The learned man assumes that either verdant nature or powerful spiritual beings will occupy the halls of Poetry. His reference to the “starry sky” could be alluding to Kant’s declaration, from the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), that he was moved to awe and wonder by “the starry sky above me and the quiet law within me.” Those words were chosen by Kant’s friends for his tombstone and became a commonplace expression.

21. “connection with Poetry.” As an entity affiliated with darkness and shady matters, the shadow claims to be completely at home in the sphere of poetry. Dwelling there, he manages to discover his innermost being and to develop depth despite the fact that he is a two-dimensional being. Poetry here fulfills its mission of cultivating profundity, but it does not succeed in achieving moral improvement of any kind.

22. “because I know you won’t put it in a book.” The learned man has not only liberated his shadow by declaring it to be free, he has also abdicated the power to tell his story because he fears being perceived as an imitator. This double disavowal, first of his shadow, then of his narrative voice, deepens the identity crisis he faces even as it is symptomatic of an attempt to achieve singularity. “The Shadow” is, of course, told by a third-person omniscient narrator, not by the learned man.

23. “I ran up and down the streets.” The shadow, despite the fact that he has become a man, still resembles a shadow. That he stays at home when it rains (a time when shadows disappear) is further evidence that he has not completely evolved into a human being.

24. “I saw what no one else could, or should, see.” The shadow asserts his kinship with poetry and describes himself as a creature who can pry, eavesdrop, and snoop, gaining access to the secret life of the soul. And yet he does not translate this knowledge into any kind of poetic insight, using his observations for nothing other than venal purposes. Dickens, to whom Andersen had paid a visit in 1857 when he traveled to London, writes about a proposed commentator for a periodical he was planning and sketches a character much like Andersen’s spectral figure: “a certain SHADOW, which may go into any place, by sunlight, moonlight, starlight, fire-light, candlelight, and be in all homes, and all nooks and corners, and be supposed to be cognizant of everything, and go everywhere, without the least difficulty. . . . a kind of semi-omniscient, omnipresent, intangible creature” (Forster, II 419–20). Like the nightingale in the tale of that title and the daughters of the air who appear at the end of “The Little Mermaid,” the shadow has the capacity to supervise and surreptitiously monitor behavior.

25. “the good, the true, and the beautiful.” The learned man is committed to a Platonic vision in which reality is nothing but a refraction of the world of ideas in which the good, the true, and the beautiful are one. His search for the good, the true, and the beautiful reveals an inability to engage with reality, and that inability has real consequences, for the shadow emerges to claim all the materialistic, venal, sinister traits that the learned man has worked so hard to purge from his life.

26. The shadow was now the master, and the master was the shadow. Despite the fact that the shadow does not become fully human, he begins the process of overshadowing his host. The learned man has become nothing more than a shadow of himself. The interplay between shadow and self continues in a verbally playful manner but in a situation charged with malice. The learned man may be kind and gentle, but his shadow operates with calculation and ruthlessness, aiming for a complete reversal of positions.

27. “to call you by yours.” The shadow claims to meet the learned man halfway, but he is, of course, gaining the upper hand by offering to use the informal form of address. The reversal in forms of address marks the point at which subjection becomes complete. The shadow has now become “the real master.”

28. the disease of being able to see too well. The princess suffers from a malady that the shadow may well understand, since he has “seen everything.” That she immediately perceives the shadow’s lack of a shadow and understands that the failure to grown a beard is simply a cover for deeper problems suggests that she may have some redeeming virtues, but in fact she is easily taken in by the shadow and proves less insightful than she initially appears. She may see too much, but she cannot see through the shadow and his machinations.

29. She was light on her feet, but he was even lighter. The narrator continues to engage in word play, with the shadow, despite his darkness, being “light,” if only in the sense of insubstantial and without weight.

30. “What a man he must be to have such a wise shadow!” It is telling that the learned man retains the quality that has been his chief attribute all along, as signaled in the adjective “learned.” In the end, however, even his intellect is appropriated through the clever ruse of the shadow, who understands how to get the upper hand on every count.

31. “I’m going to tell everyone the whole story.” The scholar decides to tell his story at last, but too late to ensure his own survival. Ironically, he fails to write about himself for fear of being perceived as an imitator, and ends up, not just as a shadow of himself, but as a shadow of his shadow, doomed to mime his every move. Storytelling has been linked with survival ever since the time of Scheherazade, who told her thousand and one tales to delay her execution by King Shariyar. For the scholar, the impulse to tell his story and thereby save his life comes too late, for the shadow has already secured the power he needs to engineer an execution.

32. It was quite a wedding! Ending like a fairy tale, with a wedding between the title character and a princess and the execution of a “villain,” the story also violates the conventions of the fairy tale in perverse ways, punishing the figure who seeks the good, the true, and the beautiful while rewarding the sinister character who uses deception to win the hand of a princess. “The Shadow” is a kind of anti–fairy tale, reversing the terms of the genre. Only a few of Andersen’s fairy tales end happily with marriages, and tales like “The Tinderbox” and “Thumbelina,” for example, are closer to anomalies than representative tales.

33. they had taken his life. The final sentence can be read as having a double meaning, for the shadow and the princess kill the scholar but also take their life from him—that is, they exist because of him. “The Shadow” can be read as a fable about how characters take their life from their authors and then, once they become “immortal,” also outlast their authors, putting them in the shade. Andersen had originally planned to have the learned man beheaded, but friends urged him to tone down the violence. Koelb notes that the conclusion takes us into morally troubled waters but also points to an artistic triumph: “Although the shadow has succeeded in wiping his master from the page, ‘The Shadow’ has effectively displaced another progenitor, Chamisso’s Peter Schlemihl. The defeat of the author, his absolute destruction in terms of the plot, is his great victory” (Koelb, 220). “The Shadow” is not at all about a “once-upon-a-time” existence in which a character emerges from a position of subordination to defeat villains and live happily ever after. It stages the struggles of a self divided against itself and reveals that we ourselves sometimes produce our worst enemies.