Psychen

Andersen reported that this story was inspired by an incident that took place in Rome: a beautiful statue of Bacchus was unearthed when a grave was being dug for a young nun. The blend of allusions to the myths of classical antiquity and the biblical stories of sin and redemption also connect Andersen’s story to the German Romantics, particularly E.T.A. Hoffmann and Josef von Eichendorff, who were enamored of Italy and used it as the setting for their novellas. Albert Küchler, a Danish artist who became a monk, may have been the model for the sculptor in “The Psyche.”

“The Psyche” was published the same year as Andersen’s “The Ice Maiden,” a terrifying tale about an icy kiss of death from a Nordic femme fatale. In Stravinsky’s musical adaptation of that tale for the ballet Le baiser de la fée (1928), the fairy in the title is a muse who captures the hero for the world of art. From the start, with his first novel The Improvisatore, Andersen was troubled by the nature of art, which aspires to the divine but often descends into the demonic. In “The Psyche,” as in “The Shadow” and other works written in the last decade of his life, he was committed to exploring the complications of a life devoted to creativity and to a cult of beauty.

At dawn, a large star, the bright morning star, shines through the red clouds. Its beams tremble on the white wall,2 as if it were planning to write a story there about everything it has seen here and there over the thousands of years it has looked down on our earth as it rotates.

Let’s listen to one of its tales.

A short time ago—although the star’s short time ago is centuries in human time—my beams shone down on a young artist.3 He was living in the city of the popes, in Rome, one of the world’s greatest capitals. Many things have changed there since that time,4 but they have not changed as quickly as humans alter in the course of moving from childhood to old age. The imperial fortress was then, as now, a site of ruins. Fig trees and laurels were growing among the upturned columns, and, in the baths, the walls were still gleaming with gold even though they had been destroyed. The Coliseum stood in ruins. Church bells were ringing, and the fragrance of incense filled the air as processions with lighted candles and magnificent canopies passed through the streets. A holy event was taking place, and art too was hallowed and considered sacred. The world’s greatest painter, Raphael,5 and the greatest sculptor of his time, Michelangelo, were living in Rome at the time. The Pope himself held both in high esteem and honored them with his visits. Art was supported, revered, and rewarded.6 Nonetheless, not all talents and abilities were seen and acknowledged, even back then.

LORENZ FRØLICH

Down a little, narrow street, there was an old house that had once been a temple. In it lived a young artist, poor and unknown but with many young friends—artists all, young in spirit, mind, and thought. They told the artist that he was blessed with talent and skill but that he was a fool for lacking confidence in those abilities. He was always destroying what he had sculpted from clay. Never satisfied with what he made, he could not finish anything, and of course you had to be able to do that if you wanted to be known, celebrated, and make a living.

“You’re a dreamer!” his friends told him. “And that is your misfortune! Your problem is that you haven’t yet lived and enjoyed life in the way that it should be savored, in great big healthy doses. It is precisely when you are young that you can and should become one with life! Look at the great master Raphael, whom the Pope honors. He is not beyond enjoying bread and wine.”

“I’ll say. And he’s likely to gobble up the girl at the bakery too, the charming Fornarina,” said Angelo, one of the rowdiest of the artist’s young friends.

Yes, indeed, the friends all weighed in on the matter, each according to his age and attitude. They were intent on drawing the young artist into a life of merriment, wildness, what could also be called madness. And sometimes, for a moment, he would feel the desire to succumb. His blood was hot, and he had a lively imagination. Occasionally he would join in the spirited banter and laugh noisily with the others. But the thought of what they called “Raphael’s carefree way of living” disappeared like the morning mists when he saw the divine brilliance of the master’s great paintings or when he stood in the Vatican before the beautiful statues that great artists had shaped from blocks of marble so long ago. His chest would heave deeply with longing, and he could feel a power—noble, holy, uplifting, great and good—inspiring him to create the same kinds of figures, to carve them from marble. He was determined to create an image of what made his heart soar up to the firmament. But how and in what shape? His hands molded soft clay effortlessly into beautiful shapes, but the very next day, as always, he would destroy what he had created.

One day, he happened to pass by an opulent palace, one of many in Rome, and he paused before a wide entrance with open gates and saw inside colonnades adorned with statues, surrounding a little garden filled with the most beautiful roses. Enormous white calla lilies with lush green leaves were growing in the basin of a marble fountain, where clear water was splashing. The contours of a delicate, graceful, marvelously beautiful young woman could be seen gliding through the garden and past the fountain—the daughter of the noble family living there. He had never before seen such a beautiful woman. Wait! Once before he had seen a beauty like that, painted by Raphael, painted as Psyche, in a Roman palace. Yes, her portrait had been there, and here she had come to life and was walking around.7

The artist carried her image in his heart and thoughts. When he returned to his humble quarters, he began to mold a Psyche in clay. The figure was the wealthy, young daughter of Rome, a noble maiden, and, for the first time ever, he was satisfied with his work. It meant something to him: it was she. When his friends saw the statue, they were overjoyed. Here was the work of true genius that they had always known to be there and that the world would now also appreciate.

Clay is supple and lifelike, but it does not possess the whiteness and permanence of marble. This Psyche had to come to life in marble,8 and the artist already owned a precious slab of marble. For years, it had taken up space in his parents’ courtyard, with broken glass, stalks of cabbage, and artichoke leaves collecting around it and soiling its purity.9 But on the inside, the slab was as white as shining mountaintops covered with snow. Psyche would emerge from this piece of marble.

Now, it happened one day (the morning star did not report this because it never knew about it, even though we do) that a party of Romans stopped in the narrow, uninviting street. The carriage in which they were traveling was parked at the top of the street, and the visitors walked down to the house in order to see the young artist’s work, which they had learned about only by chance. Who were these distinguished visitors? Poor young man! Or should we call him a young man who will become happy, perhaps too happy? The young maiden herself was right there in his dwelling, and what a smile broke out on her face when her father declared: “Why, it’s your image, as you live and breathe!” That smile, that gaze—what a wondrous look she gave the young artist! It cannot be carved, and it cannot be created. It was a look that inspired him and ennobled him—but it also crushed him!10

“Psyche must be realized in marble,” the rich gentleman proclaimed. And those were words of life for the dead clay and for the heavy marble block, just as they animated the young man, who was deeply moved. “When you have completed the work, I shall buy it,” the noble gentleman added.

It was as if the humble studio had suddenly come to life. It was lit up by joy and good cheer, and accompanied by a buzz of activity. The bright morning star watched as the work progressed. The clay itself had come to life since she had been there. It molded itself into the familiar features with heightened beauty.

“Finally I know what life is!” the artist rejoiced. “It is love! It is sacred devotion to the ecstatic rapture of losing yourself in beauty! What my friends called life and pleasure is as unreal and as fleeting as the bubbles made by yeast in dough. It has nothing to do with the pure, divine altar wine that consecrates life.”11

The marble block was hoisted into place, and the chisel began to cut away large chunks. Measurements were taken; points and lines were drawn on the stone; the work of the craftsman was done. Before long, the stone began to transform itself into Psyche, a figure of beauty as graceful and perfect as God’s own image of the maiden.12 The weighty stone was turned into a hovering, graceful, sprightly Psyche with the smile of divine innocence that had been captured in the mirror of the young sculptor’s heart.

The star of the rosy-colored dawn saw it and knew right away what was stirring the young man’s soul. It understood why his cheeks kept changing color and why his eyes were flashing while he was representing what God had created.

“You are like one of the masters from ancient Greek times,” his friends told him. “Soon the entire world will be admiring your Psyche!”

“My Psyche,” he repeated. “Mine! Yes, she must be mine! I am like one of the artists of old who are no longer with us! God has given me this divine gift and raised me to be the equal of nobles!”13

He fell to his knees and wept tears of gratitude to God. But he soon forgot about God and thought only of her and of her image in marble—his Psyche who was standing there as if she had been formed of snow,14 blushing in the morning sunlight.

He was supposed to go see her—the living, breathing Psyche, whose words were like music. Finally he could announce the news in the stately palace that the marble Psyche was finished. He entered the gates, crossed the open courtyard, where water was splashing from the mouths of dolphins into marble basins and where calla lilies and fresh roses were blooming in abundance. He walked into a long, lofty entryway, with walls and ceilings painted in beautiful colors and covered with coats of arms and works of art. Uniformed servants, haughty and pretentious, swaggering like sleigh horses decked out with bells, strutted up and down. A few of them even stretched out lazily and boldly on the carved wooden benches, as if they were the masters of the house.

The artist explained his errand and was escorted up polished marble steps covered with thick carpets. Marble statues lined both sides of the staircase. He walked through magnificent rooms with paintings and floors of mosaic. The sight of so much brilliance and finery was overwhelming, but he quickly regained his composure. The noble master of the house received him kindly, even warmly. When the artist was taking his leave, he was told to visit the young signorina, who wished to see him again. A servant took him through more magnificent rooms, until he was ushered into a room where she was the most brilliant ornament.

The young woman spoke to him, and even a prayer of mercy or church song would not have had the same great power to melt his heart and lift his soul. He took her hand and pressed it to his lips. Even rose petals were not as soft as that hand, but flames—flames of some kind—leaped from it. He felt grand sentiments coursing through him. Words flowed from his lips, but he had no idea what he was saying. Is a volcano aware that its eruptions produce fiery lava?15 He confessed his love to her. She drew herself up before him, astonished, offended, and proud, with a look of contempt on her features, as if she had just touched a cold, wet frog. Her cheeks turned red; her lips grew pale; and her eyes flashed pitch-black, as dark as the night.

“You madman,” she cried. “Go away! Get out of my sight!”16 And when she turned her back on him, the face of beauty bore a resemblance to that petrifying face with serpent hair.17

The artist descended the stairs in a stupor and found his way back to the street. He managed to reach his lodgings, moving like a sleepwalker, but came to in a fit of rage and pain. Taking his hammer in hand, he raised it high in the air and was about to smash the beautiful marble image. He was so beside himself that he did not even realize that his friend Angelo was standing right next to him. With a strong grip, Angelo held his arm back.

“Are you mad? What’s the matter?”

The two struggled, but Angelo was stronger and prevailed. Exhausted and breathing heavily, the young artist flung himself into a chair.

“What happened?” Angelo asked. “Pull yourself together. Tell me what happened!”

But what could he say! And since Angelo could not understand his ravings, he gave up.

“You’ll get into trouble with your eternal dreaming! Be a man, like your friends, and stop living in a fantasy world. You’ll go crazy. Get a little tipsy, and you’ll sleep it off! A beautiful girl can be your healer. The girls from the campagna18 are as beautiful as your princess in the marble castle. They are all daughters of Eve,19 and when you’re in paradise, you won’t be able to tell them apart. Take the advice of your Angelo. I’m your angel now, your angel of life! The time will come when you will be old, and your body will fall apart. Then, on a beautiful, sunny day, when everyone else is laughing and having a good time, you’ll lie there, like limp straw with no life left in it. I don’t have much faith in what the priests tell us about life beyond the grave. That’s a nice fantasy, a fairy tale for children—quite pleasant if you can persuade yourself that it’s true. As for me, I deal in reality. Come along with me! Start acting like a man!”

The artist was able to drag himself along, at least for the moment. He felt fire in his blood. A change had taken place in his soul, and he sensed a deep desire to move away from the familiar and to tear himself loose from his old self. And so he followed Angelo.

On the outskirts of Rome, there was a tavern frequented by artists. It had been built into the ruins of ancient baths. Large yellow lemons could be seen among dark, shining leaves and covered part of the old reddish-yellow walls. The tavern consisted of a vaulted chamber, almost like a cavern located in the ruins. Inside it, a lamp was burning before the image of the Madonna.20 A fire was blazing in the hearth, and there was much cooking and roasting. Outdoors, beneath the lemon and laurel trees, there were tables covered with food.

The two young men were greeted with shouts of joy by their friends. They didn’t eat much, but they drank a lot, and that raised everybody’s spirits. There was singing, and someone was playing the guitar. Then the saltarello21 was played, and everyone began dancing merrily. Two young Roman girls who were working as artists’ models joined in the dance and festivities—two charming Bacchantes,22 not as lovely as Psyche, to be sure, not delicate, beautiful roses, but fresh, sturdy, vibrant carnations.

How hot it was that day! There was fire in the blood, fire in the air, fire in everyone’s eyes. Gold and roses were glowing in the air; life was gold and roses.

“At last you have joined us. Let yourself go with the flow all around you and in your soul.”

“I’ve never felt so healthy, so full of joy,” the young artist said. “You’re right, you were all right. I’ve been a fool and a dreamer. We should live in reality and not in fantasy.”

Singing and playing their guitars, the young artists left the tavern and strolled through the narrow streets under the clear, starlit skies. The daughters of the campagna, those colorful carnations, accompanied them.

They returned to Angelo’s room, where colored sketches, folios, and sensuous, lustrous images were scattered all around, and their voices became quieter but were no less animated. On the floor there were many sketches23 that resembled the daughters of the campagna, showing their robust beauty from many different angles. And yet the women were far more attractive than the images. Every candle on the sixarmed candelabra had been lit, and it was blazing and glowing. And from deep within the artist’s soul, something divine was also blazing and glowing.

“Apollo! Jupiter! I’m carried aloft to your heavens and into your glory. The flower of life in my heart has blossomed for the first time.”

Yes, it blossomed, and then it bent, broke, and a nauseating vapor arose from it, blinding his eyes, numbing his thoughts, and extinguishing the fireworks of the senses. Everything turned black.

He was back in his room again, and there he sat on his bed, collecting his thoughts. “Shame on me!”—those words came out of his own mouth, from the depths of his heart. “Get out of my sight, be gone, you wretched man.” He heaved a deep, painful sigh.

“Go away! Get out of my sight!” Those words, the words of the living Psyche, resounded within and were spoken by his own lips.24 He buried his head in the pillow, and, with confused thoughts in his head, he fell asleep.

He awoke the following day at dawn with a start and tried to collect his thoughts again. What had happened? Had it all been a dream? Had he just dreamed about going to see her, about the trip to the tavern, and the evening spent with those two purple carnations from the campagna? No, it was all reality, a reality that he had not known up until now.

The bright morning star shone through the purple-tinted air. Its rays fell on him and onto the marble Psyche. He began to tremble when he looked at the image of immortality. His gaze seemed to taint the work. He threw a sheet over the statue, and then he touched it one more time to uncover the figure, but he was no longer able to look on his own work.

The artist sat alone all day long, quiet, gloomy, and absorbed in his thoughts. He did not hear a bit of what was going on outdoors. No one knew what was stirring in that human soul.

Days passed and weeks went by. The nights seemed endless. The twinkling star saw him rise from his bed one morning, pale and feverish. He walked over to the marble statue, pulled back the sheet covering it, and gazed one last time, with pain and longing, at his work. And then, staggering under its weight, he took the statue down into the garden, where there was a dried-up well that was now nothing more than a hole in the ground. He lowered Psyche down into it,25 threw dirt over her and then scattered dry sticks and nettles over the spot.

“Go away! Get out of my sight”—that’s all there was to the burial service.

The morning star witnessed everything in the rosy-red air, and its beams illuminated big tears on the deadly pale cheeks of the young man. Feverish and mortally ill, he was said to be on his deathbed.

Brother Ignatius came to see him often, as both friend and physician. He brought the consolations of religion to the ailing artist and told him about the peace and happiness that comes from the church, and he spoke of man’s sin and about grace and the peace found through God. His words were like warm sunshine landing on tilled soil that sends forth clouds of mist, fantastic thoughts, and images that were also reality. The ailing artist reviewed human life from these floating islands. It was nothing more than error and deception, for him as for everyone else. Art was nothing but a sorceress that fuels vanity and earthly desires. We betray ourselves, our friends, and God. The serpent within keeps telling us: “Taste and you shall become like God.”26

LORENZ FRØLICH

It seemed to him that for the first time he understood himself and had finally found the road to truth and to freedom. In church you could find God’s light and wisdom, and, in the monk’s cell, you could find the peace needed by the human tree to strike roots and grow through all eternity.

Brother Ignatius strengthened his resolve, and his mind was made up. A worldly creature was about to become a servant of the church. The young artist renounced the world and entered the monastery.

The brothers received him warmly, and it was a festive day when he took his vows. It seemed as if God was standing right there in the sunlight of the church, radiating his presence from the sacred images and the shining cross. When he was in his little cell that evening at sunset, he looked out from his window across old Rome with its desolate and its great, if dead, Coliseum and saw the city adorned in its springtime garb, with its acacias in bloom, its fresh evergreens, its abundance of roses, its glistening lemons and oranges, its waving palms. Then he felt moved and fulfilled as never before. The wide, open campagna stretched out as far as the bluish, snow-capped mountains, which seemed as if painted in the sky.27 Everything melted together, breathing peace and beauty, floating, dreaming—it was all a dream!

LORENZ FRØLICH

Yes, the world here was like a dream, and dreams can last for hours and can return for hours, but life in the monastery is a matter of years, many long years.

Much of what taints humans comes from within—that much was confirmed for the artist. What flames burned in him at times! Why did the evil that he wanted so much to defy refuse to go away? He chastised his body, but the evil was coming from within. A small part of his mind wrapped itself as lithely as a snake around him and crawled with his conscience under the mantle of universal love and comforted him with these words: “The saints pray for us, the Madonna prays for us, and Jesus himself gave his blood for us.” Was it childlike innocence or the flippancy of youth that partook of grace and felt elevated by it, elevated over many others now that he had rejected the vanity of the world? After all, he was a son of the church.

One day, after many years had passed, he met Angelo, who recognized him at once.

“My boy!” Angelo cried out. “It’s you! Are you happy now? You sinned against God by throwing away the gifts that he gave you. You forfeited your mission in this world. Have you ever read the parable about the talents?28 The wise man who told that story spoke the truth. What have you earned and what have you found? Don’t you think that you are living a dream, a religion that is simply in your head, the way it is for others? What if everything were just a dream, a fantasy, and beautiful thoughts!”

“Get thee behind me, Satan,” the monk shouted and walked away from Angelo.

“The devil exists, and he is made of flesh and blood! I saw him today,” the monk muttered. “Once I gave him my little finger, and he grabbed my whole hand! But no,” he sighed, “the evil is in me and in him too, but it doesn’t weigh him down. He walks around free as a bird and lives comfortably while I struggle to find comfort in the consolations of religion. If only it were a consolation! If only everything here were just beautiful thoughts, like the world that I left behind—illusions, like the beauty of the rose-colored evening clouds, like the drifting blues of the distant mountains. Up close they look quite different. Eternity29: you are like the vast, boundless, silent seas that beckon and call and fill us with hopes. But as soon as we wade in, we start to sink, vanish, and die. We cease to exist. Deception! Go Away! Fall down!”

Without shedding any tears and completely absorbed in his thoughts, he sat down at his place of prayer, bowed down, but before whom? Before the stone cross in the wall? No, it was sheer habit that led him to assume this position.

The deeper he looked into himself, the blacker the darkness seemed. “Nothing within, nothing without! My entire life squandered.” And these thoughts grew like a snowball that became larger as it rolled along until finally it crushed him—wiping him out.

“I can’t confide in anyone or tell anyone about the worm that is gnawing away at my insides! My secret is my prisoner, and if I let him escape, I’m his.”

And the divine power within him suffered and struggled.

“God, my heavenly God,” he called out in his anguish. “Have pity on me! Give me faith! I left my mission unfulfilled. I squandered the talent you gave me. I lacked the strength, for it was not given to me. Immortality, the Psyche in my breast—go away, down with you! It must be buried like that Psyche which was the finest ray of hope in my life. She will never rise from her grave.”

The star in the rosy-red skies was shining, the very star that will some day fade and disappear even as the soul lives and shines. Its trembling beam landed on the white wall, but it wrote nothing at all about God’s glory, about his blessings, about his love, about all those things that resound in the hearts of those who have faith.

“The Psyche within me will never die! To live in consciousness? Can the unfathomable happen? Yes, yes, my being is unfathomable, and you, oh Lord, are unfathomable! Your entire creation is a wondrous work of power, glory, and love!”

His eyes were glowing, and then they dimmed. The sound of the church bells was the last thing he heard before he died. His body was lowered into soil that had come from Jerusalem and that had been mixed with dust from the corpses of pious souls.

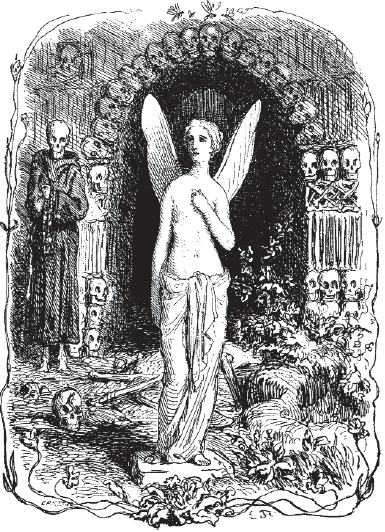

Many years later his bones were disinterred, as had also happened with monks who had died before him. His skeleton was clothed in a brown monk’s robe and a rosary was put in his hand. It was placed in the ranks with others in the cloisters of the monastery. And while the sun was shining outdoors, incense was burned indoors and the mass was read.

Many years went by, and the bones of the skeletons had crumbled. The skulls had been gathered together to make a wall around the church. There they all were—his among them—in the burning sunlight. There were many there, and no one knew their names. Nobody knew his name either. But look! Something was moving in the sockets of his skull, and it was alive! What could it be? A spotted lizard was darting around in the hollow skull, leaping in and out of the empty eye sockets.30 The lizard was now the only form of life in that skull that had once entertained bold thoughts, bright dreams, and a love of art and splendor—it had shed hot tears and aspired to immortality. The lizard jumped and then disappeared. The skull crumbled, and dust returned to dust.31

Centuries later the bright morning star could be found continuing to shine, large and radiant, as it had for thousands of years. The skies were aglow in hues of red, fresh as roses, red as blood.

A monastery now occupied the site of the temple that had been on that narrow street and had lain in ruins. A grave was being dug in the convent’s garden. A young nun had died and was to be buried at dawn. The spade hit a stone, and a dazzling ray of whiteness gleamed through the dirt. The perfect form of a shoulder made from marble emerged from the ground. The spade was guided with greater care, and the head of a woman was uncovered, and then suddenly butterfly wings appeared.32 The gravediggers lifted the marvelous figure of Psyche—chiseled from white marble and resplendent in the rose-red hues of the dawn—from the grave where the nun was to be buried. “How beautiful, how perfect she is! A work of art by one of the great masters!” people were saying. Who could that master have been? No one knew, no one had known him but the bright, shining star that had sent its beams down for thousands of years. It was familiar with the course of his life on earth, his sufferings and weaknesses, and also knew that he was a man, nothing more! But he was gone now, scattered abroad as dust is destined to be. But Psyche, the fruit of his most noble labors and the glorious work that revealed the spark of the divine in him, remained, and she would never die. She had transcended fame and fortune, and her glory would remain here on earth. She would be seen, appreciated, admired, and idealized.

The bright morning star in the rose-tinted air sent its sparkling beams down on Psyche and on the lips and eyes of her admirers, who were smiling with delight as they beheld the soul carved from a block of marble.

Everything that is of the earth will crumble and be forgotten. Only the star in the vast firmament will remember. What is heavenly will shine through the ages, and when that too has passed, Psyche will live on.33

LORENZ FRØLICH

1. Psyche. In Apuleius’s story “Cupid and Psyche” from the second century A.D., Psyche, whose name is the Greek word for “soul,” disobeys her husband Cupid and lights a lamp in order to see him. When Cupid flees, Psyche pursues him, undertaking a series of tasks, which, although not successfully completed, lead to a reunion with the beloved and bestow on Psyche immortality. The deep irony of the artist’s quest in Andersen’s story becomes apparent with the realization that, in the ancient story, Psyche acquires immortality through her marriage to a figure who embodies Eros. The two give birth to a child named Pleasure. The soul is represented in many cultures as a butterfly (symbol of metamorphosis) that leaves the body at the moment of death.

2. Its beams tremble on the white wall. The star is identified as the story’s first narrator and makes an attempt to write the story down with its rays as pen. But that act of writing remains in the realm of “as if,” and the star ends up telling the first part of the story. Although the morning star seems to witness much of what happens, the narrator occasionally has access to events that are not seen by the star (“the bright star did not report it”). The artist in the story may be haunted by anxieties about usurping God’s power to create life, but the narrator remains supremely untroubled by any possible rivalry between him and the star, who witnesses the events and tries unsuccessfully to write them down. The two seem to work in partnership, with the star as the oral teller of the tale, and the narrator as scribe, a figure who engages in the very same activity as the artist by trying to create the semblance of reality through his art.

3. a young artist. Ironically, the artist, who is intent on making a name for himself, is never given a name in the story. Unlike Raphael and Leonardo, who inspire him, he remains unknown. He may have been modeled in part on the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, who moved to Rome in 1797 and did not return to Copenhagen until 1838. While visiting Thorvaldsen in Rome, Andersen mentioned that the sculptor’s statue of Pontius Pilate was dressed more like an Egyptian than a Roman. Thorvaldsen destroyed the figure and Andersen was scolded for having forced the artist “to destroy an immortal work” (Travels, 234–35).

4. Many things have changed there since that time. The notion of metamorphosis is introduced right away in a story that sets up oppositions between permanence and change, death and immortality, the fleeting and the durable. It is no accident that the events take place in Rome, a site known as “the eternal city” even as it stands in ruins. The city had been Andersen’s travel destination on more than one occasion. Teeming with life, with lights, sounds, and scents, Rome is also seen as a place of decay and bears everywhere the signs of destruction. Ruins can be particularly attractive because they show nature reclaiming culture even as they display the remnants of that culture.

5. Raphael. In a diary entry of 1833, Andersen describes seeing Raphael’s representation of Psyche: “Went to the Palazzo Farazina, where Raphael and his pupils had painted the story of Psyche in a fresco on the ceiling.” Raphael died in 1520, and Michaelangelo lived until 1564. “The Psyche” is therefore set in sixteenth-century Renaissance Italy. In 1833, Andersen visited Raphael’s villa and drew a sketch of it. He was impressed by the violets growing in the garden and sent a pressed violet from the garden to a friend.

6. Art was supported, revered, and rewarded. The high status of art and the deference paid to it by the Pope stand in apparent contrast to modern times. The nostalgic view of a golden age in which art and religion were in harmony rather than in competition reflects Romantic views that originated in Germany and England and migrated to Scandinavian countries.

7. here she had come to life and was walking around. Like photographs, shadows, and mirrors, paintings have been seen as producing doubles that both capture the soul and can take on a life of their own. The animated portrait has a venerable history, reaching back to folktales from China, India, and Persia that depict subjects stepping out of their framed representations. Andersen, like Poe, Hawthorne, Wilde, and other nineteenth-century writers, draws on the theme to illuminate the complex relationship between an artist and his work and to reflect on the power of artists, who ceaselessly violate the biblical taboo against making images and who fashion lifelike figures that rival God’s creation. (“Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image, nor any manner of likeness of any thing that is in Heaven above or that is in the earth beneath or that is in the water under the earth,” Exodus 20:4–5.)

8. This Psyche had to come to life in marble. Among the many mythological references embedded in the tale, the story of Pygmalion is the most pertinent. Ovid’s Metamorphoses contains one story about a sculptor who has no interest in the women of Cyprus and, inspired by an image of Aphrodite, carves a woman out of ivory. He falls in love with the statue, and Aphrodite, taking pity on him, brings the statue to life. Andersen’s artist, like Pygmalion, creates a statue from an already-existing work of art—an image of an image—even if he claims to be creating the image of the Roman maiden.

9. soiling its purity. In Andersen’s work, the sublime can coexist with the impure, polluted, or grotesque, often undermining the transcendent values attributed to a person or thing. Gutters, garbage heaps, and refuse serve as reminders of mortality, decay, and transience.

10. but it also crushed him! Much as the artist appears to be enamored of the young Roman girl, he feels mortified when he realizes that he cannot duplicate the enchanting smile of the living woman.

11. “divine altar wine that consecrates life.” This allusion to the yeast used to make bread and also to altar wine is one of many references to bread and wine, and wine’s sustaining influence. Unlike Raphael, who appreciated the value of both bread and wine, the artist makes a distinction between the two. The symbolic power of the sacrament figures importantly in a story about art’s power to represent the soul.

12. as graceful and perfect as God’s own image of the maiden. The artist’s creation is repeatedly set in opposition to God’s creation of man. Adam was made from what has variously been translated as dust, earth, and clay, and God breathed life into him. The artist too begins with clay, then translates his clay image into the refined purity of marble. The sacred breath may never enter his creation, but the statue endures long after God’s own image in the maiden is gone.

13. “the equal of nobles!” The aspirations of the artist go beyond sculpture. His success, he believes, will lead to social mobility as well as to fame, a connection that was not trivial in Andersen’s mind.

14. as if she had been formed of snow. The white of the statue is compared repeatedly to snow, to icy mountaintops, and to other natural marvels. The artist’s art consists precisely of creating something that does not appear to be artifice but rather is completely natural. Through snow, the statue comes to be linked with Andersen’s other women in white: the Snow Queen and the Ice Maiden, both deadly to men.

15. Is a volcano aware that its eruptions produce fiery lava? In The Improvisatore, Andersen describes an amorous encounter using the same terms, but literally in this case, rather than figuratively, since the protagonist, Antonio, lives in Naples: “When I reached the street, everything was in flames, just like my blood! A current of air blew the heat toward me. Vesuvius was glowing with flames—eruptions followed one another rapidly, illuminating everything around. . . . The sea was shining like the fire of the red lava, which was rolling down the mountain. Wherever I looked, I could see her standing there, as if painted with flames.”

16. “Go away! Get out of my sight!” The young woman’s words anticipate what the artist will say first to himself after the night of revelry, then to the statue of Psyche when he lowers it into the well, and finally to his friend Angelo who tries to persuade him to return to life. In this last instance, the artist uses the term “Apage Satanas,” emphasizing a need to exorcize the devil. On two other occasions the phrase is repeated by the artist, who seems to labor under the compulsion to appropriate the words of the woman whose image he created. Ironically, the artist’s efforts to remove the statue from sight, to lower her into a grave, and to bury her in darkness lead to the return of the repressed.

17. bore a resemblance to that petrifying face with serpent hair. The artist transforms his Psyche into a Medusa figure, who returns his petrifying gaze with her own stony look. In October 1833, after seeing Leonardo da Vinci’s Medusa, Andersen wrote to his friend Henriette Wulff: “The head has something magical about it that attracted me—the foam of the abyss in its most beautiful shape. It is a hell that has created the head of a Madonna with warm poison streaming out of her mouth. The serpent’s hair is moving as the person beholding it becomes petrified.”

Andersen expressed his horror at how the animating power of imagination can devolve into the petrifying power of a Medusa in those who are mad. Visiting an asylum, he observed: “Imagination, this life’s best cherub, that conjures up an Eden for us in the sandy desert—is here a frightful chimera, whose Medusa-head petrifies reason and thoughts, and breathes a magic circle around the unfortunate victim, who is then lost to the world” (Bøggild, 79).

18. “The girls from the campagna.” “Campagna” is the Italian term for countryside, and the Roman campagna is the region around Rome. For Andersen, Rome and its surroundings were “like a book of fairy tales . . . where new wonders are constantly being uncovered so one can immerse oneself in a world of fantasy” (Travels, 256).

19. “They are all daughters of Eve.” That a painter named Angelo who is dismissed with the phrase “Apage Satanas” tries to convince the artist that women are all tainted by sin shows how deeply the story is invested in staging a religious debate about sin and innocence and about death and immortality in gendered terms.

20. a lamp was burning before the image of the Madonna. The untroubled juxtaposition of sacred and profane in the tavern reveals the degree to which the artist suffers from self-division in a unique way, with his art preventing him from partaking of the pleasures of life and the consolations of religion. Note too that the tale features both the Madonna and the Medusa.

21. saltarello. The saltarello was a lively dance whose origins can be traced to thirteenth-century Naples. It is in triple meter and is named after its characteristic leaping step, from the Italian verb saltare (“to jump”). The dance became part of the popular traditions of the Roman Carnival and appears in Felix Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony, which was written after the composer had attended the Roman festivities in 1831. In his travel diaries, Andersen describes seeing girls in Rome dancing the saltarello. The Italian dance made a strong impression on him, and during his second visit to Rome he bemoaned the fact that he no longer heard “tambourines ringing in the streets” and that the “young girls dancing the saltarello” had disappeared (Travels, 256).

22. two charming Bacchantes. The allusion to Bacchus is a reminder of the inspiration for the story—a statue of Bacchus rather than Psyche. Andersen develops in this story a distinction that Nietzsche famously made between the Apollonian and Dionysian—the serene world of Apollonian appearances, beauty, and light versus the fluid, sensual, orgiastic union of opposites in the cult of Dionysus. Angelo’s encouragement to “Let yourself go with the flow all around you” is a reminder that the artist is turning from the pleasures of the Apollonian to the delights of the Dionysian.

23. On the floor there were many sketches. The sketches of the girls from the campagna are not part of a cult of art but come to be connected, through their position on the floor, with refuse.

24. resounded within and were spoken by his own lips. If the artist first imitated the living Psyche by creating a sculpture of her, he now mimics her words, internalizing her reproaches to him and repeating them to himself.

25. He lowered Psyche down into it. Just as the block of marble was covered by refuse, so the statue returns to the earth, covered with leaves and dirt. In lowering the statue into the ground, the sculptor buries it (as if it were a living thing), represses it (trying to bury the painful conflict it produces in him), and returns it to the earth (giving it back to Mother Nature).

26. “Taste and you shall become like God.” These are the words from Genesis 3:5, used by the serpent to tempt Eve: “You shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.”

27. which seemed as if painted in the sky. The artist has obviously not been completely converted, for God’s presence seems to radiate from images and symbols in the church, and he looks at God’s creation, not as nature, but as if it were a beautiful work of art.

28. “Have you ever read the parable about the talents?” Matthew 25:14–30 tells the parable about the talents, which are not talents in the sense of abilities or aptitudes but units of weight or currency: “Again, it will be like a man going on a journey, who called his servants and entrusted his property to them. To one he gave five talents of money, to another two talents, and to another one talent, each according to his ability. Then he went on his journey. The man who had received the five talents went at once and put his money to work and gained five more. So also, the one with the two talents gained two more. But the man who had received the one talent went off, dug a hole in the ground and hid his master’s money.” The master returns and rewards the first two servants, who have used their talents wisely: “For everyone who has will be given more, and he will have in abundance. Whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken from him.”

When Andersen’s compatriot the Danish artist Albert Küchler proposed that Andersen join an order to which he had converted in Rome and “live in peace with God,” Andersen replied quickly: “I could stay here for a few days, and then I would have to leave, go out in the world again . . . live in it, be in it” (Travels, 339).

29. Eternity. Eternity is the word that Kai is trying to form from blocks of ice in “The Snow Queen.” The search for immortality in “The Psyche” is also connected with whiteness, purity, and cold, hard surfaces.

30. leaping in and out of the empty eye sockets. The story turns in many ways on the visual, on beautiful images and their seductive power. The gaze, sight, vision, light, and blinding are further emphasized in the repeated invocation of the morning star, which beams down and witnesses the events taking place. The image of the white skull with its dark sockets not only negates the beauty of the “immortal” marble sculpture but also reveals that the power of vision itself is only fleeting.

31. dust returned to dust. In Genesis 3:19 God tells Adam and Eve: “By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.”

32. butterfly wings appeared. Ironically, the butterfly appears only when the statue is unearthed, not when the artist’s bones are disinterred. As noted, Psyche means both soul and butterfly in Greek. Andersen habitually connected swans, butterflies, and ballerinas in the many whimsical paper cuttings he created over the years at social events. Butterflies, related through flight to the many avian creatures in Andersen’s stories, appear frequently in the fairy tales, most notably in “Thumbelina” and in a story about a winged bachelor called “The Butterfly.”

33. Psyche will live on. Andersen develops a strong link to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a work that establishes a firm bond between poetic artistry and immortality. If Ovid ends his work about the metamorphic nature of creativity by confidently declaring “Vivam” (“I shall live”—meaning both the book and its creator), Andersen concludes by emphasizing that the work of art will triumph over its creator and attain the immortality for which he longed. Despite the artist’s efforts to plunge the statue into darkness, to lower it into the nether regions, and to bury it and return it to the earth, the statue emerges in all its pure, gleaming, transcendent glory, even as the monk’s white skeletal remains (the skull through which the lizard darts) turn to dust.