On Wednesday morning Zoey arrived at the coffee shop a few minutes earlier than the day before. She found Henry in the back standing before The Photograph, apparently lost in thought. In a reversal of their first encounter the day before, this time it was she who startled him. “ ’Scuse me,” she said.

He jumped slightly. “Ah, Zoey!” he exclaimed. “I was just enjoying our favorite print.”

“Sorry,” she said, adding, in exactly the same words he’d used with her the day before: “Didn’t mean to sneak up on you. You were pretty focused there.” She grinned, and he gave a mild laugh.

“Good memory,” he said.

She gazed at the harbor scene again, then turned back to him. “I was wondering . . .” She hesitated, trying to figure out how to put it. “Yesterday, when you said, if I could afford my coffee, I could afford that photograph? That I might be richer than I think?”

Henry nodded.

“What did you mean, exactly?”

He cocked his head and put one finger to his lips for a moment, then said, “Let me ask you this: For you to be able to afford to buy this print, what would have to change?”

“Frankly, I’d need a job that paid more than I make now.”

“Ah,” he said. Then: “Do you mind if I get personal?”

“How could I mind?” said Zoey. “I mean, you’ve already drawn my tombstone. If that’s not personal, I don’t know what is.”

“Excellent point,” said Henry with a smile. “Where do you work again? Down in Lower Manhattan, you said?”

She nodded. “One World Trade.” She briefly described her job at the travel magazine.

“I’d imagine that would pay pretty decent money,” said Henry.

“Decent,” she agreed, “but not exactly staggering. And living in Brooklyn is expensive.”

“Indeed. If I may ask, how long have you been in the workforce, more or less?”

“About six years.”

“All right. Enough time for a bright young person to advance in her position. My guess is you’re earning a bit more now than you were six years ago. True?”

“True,” said Zoey.

Henry nodded again. “So, are you richer today than you were six years ago as a result?”

Zoey blinked. “Richer?” She spoke the word as if it were in a foreign language.

“Do you, for example, have more disposable cash to spend on whatever you want? A little nest egg tucked away?”

In fact, Zoey had gotten a good bump in pay two years earlier, when Barbara promoted her from assistant editor to associate editor. But it seemed as if the more she made, the more it cost her just to live. If anything, she was deeper in the red than ever.

“Richer,” Zoey repeated. “No, I would have to say, I am not richer.”

“Well, you’re not alone. I read a fascinating survey the other day. It said half the people in this country could not put their hands on an extra $400 even in the event of an emergency. Seven out of ten describe themselves as ‘living paycheck to paycheck,’ and many even put their everyday living expenses on credit cards.”

“Really.” Zoey was not surprised to learn that so many people were in the same boat she was. After all, wasn’t that why her travel magazine was so popular? People loved to thumb through pages of adventures they couldn’t afford to have themselves.

“Here’s where it really gets interesting,” said Henry. “When asked why they didn’t save more or make some sort of retirement plan, nearly all the survey respondents gave the same answer: ‘Not enough income.’ ” He chuckled. “At least, that’s what they all said. It’s not true, of course. More income wouldn’t help their situation at all.”

Zoey felt her brain snap to attention. “Wait—what?” She must have misheard him. “More income wouldn’t help? But . . . that’s exactly what would help!”

Henry shook his head sadly. “Not really. Most people, when they have more income, just spend it on more stuff.”

“That’s—” That’s not true, Zoey was about to say. That’s not what I do, anyway.

But was that true?

“How often do you read,” the barista continued, “about some movie star, pop star, or sports star whose career skyrockets and they’re suddenly worth millions, and the next thing you know they’re broke?” Zoey had in fact read a story exactly like that, just the week before. “How many lottery winners end up in debt? For these folks, making the money isn’t the problem, you see. The problem is keeping it.

“The strange truth, Zoey, is that earning more money—even outrageous amounts of money—does not necessarily lead to wealth. Why not? Because most people, when they earn more, simply spend more. Earnings are like the tide, you see, and your spending is like a boat. When the tide rises, the boat rises with it.”

He cast his eye around the coffee shop, then back at Zoey. “Do you still have a little time before you have to go catch your train?”

“I do,” she replied. After all, wasn’t that exactly why she’d started out early this morning? As she followed Henry back to the little high-top table, she considered the image he’d just described: Earnings are like the tide, and your spending is like a boat.

Until it capsizes, she thought. Or ends up run aground in a desert.

“Wealth, financial freedom?” said Henry as he reached the table and turned back to face her. “Not that complicated. It’s a simple three-step process.”

“Let me guess,” said Zoey. “Write a Top-40 song, hit the lottery, and have a rich great-aunt who’s accident-prone?”

Henry laughed as he sat up on his stool. Zoey took the seat she’d had the day before.

“I call them the Three Secrets to Financial Freedom,” said Henry. “Although that’s perhaps a bit grandiose, because they’re the kind of secrets that lie hidden in plain view. Everyone thinks they know about them, but hardly anyone does them.

“Let me tell you how the first secret works.”

“All ears,” said Zoey. Eccentric, but insightful. For the first time, she wondered what Henry’s story was—where he came from, and how he had ended up working at a little coffee shop in Brooklyn.

“If I may ask,” Henry was saying, “how many hours did you work last week?”

“Forty, more or less.” It was really more like fifty, but close enough.

“All right. Now, how many of those hours did you work for yourself?”

Zoey started to reply but stopped before getting a word out. All of them? None of them? “I’m . . . I’m not clear on what you mean. Worked for myself, how?”

“Worked for yourself, as in, the money you earned went to you. To building your life. To investing in Zoey.”

“Okay.” She paused, then said, “I’m not really sure how to answer that.”

“Well, let’s look at it.” He opened his well-worn Moleskine to a fresh page, took out his brushed steel drafting pencil, and began sketching as he talked.

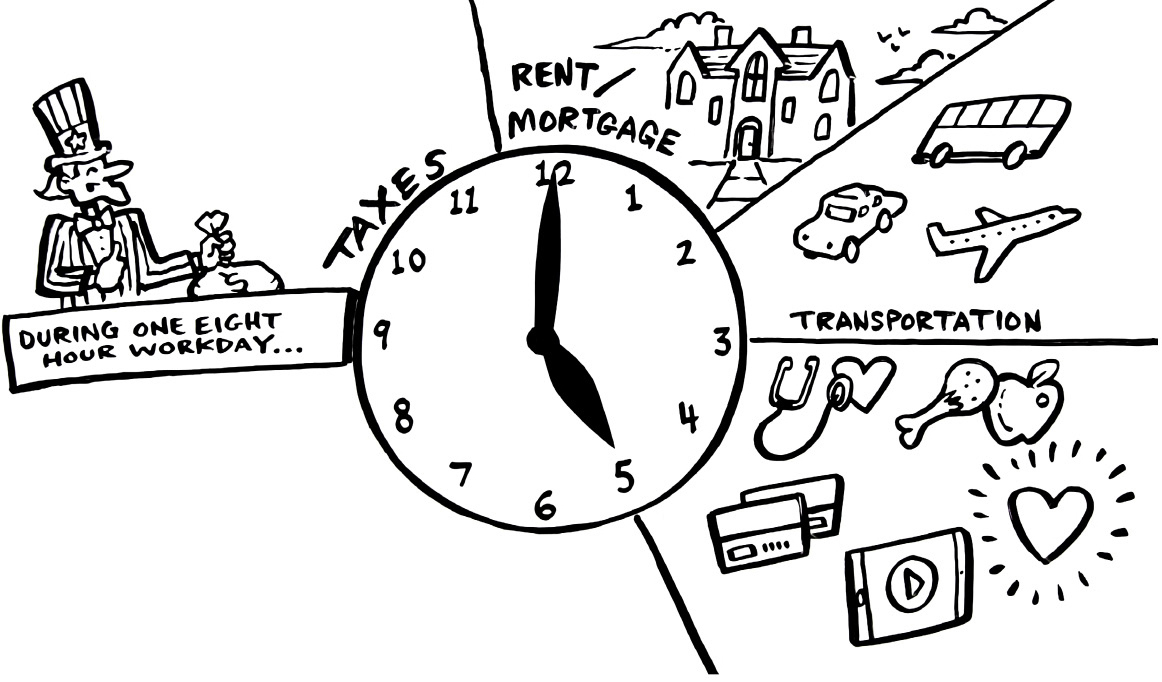

“Let’s say you start work at nine. Typically the pay you earn from nine to eleven thirty comes right off the top and goes straight to taxes.”

He drew a clockface, blocking off the space from nine to eleven thirty and filling it with a bag of money and a tall, bearded Uncle Sam.

“Wow,” murmured Zoey. “I never thought of it that way.”

Henry nodded. “Kind of makes you want to come to work after lunch.” He chuckled. “Then, from eleven thirty to two, you’re paying your . . .” He glanced up at her. “Mortgage? Rent?”

“Rent,” said Zoey. She was struck by how he sketched—a few strokes, sure and rapid, and he was done. The illustration seemed to spring complete from the tip of the pencil, as if it had been waiting in there to pop out.

“All right. Rent and utilities. From two to three typically goes to transportation costs. And from three to five, it’s everything else: health care, entertainment, debt, credit cards . . .”

“Student loans,” added Zoey.

“Ah, yes,” he said. “Student loans. Vicious things. And of course groceries—”

“Eating out, mostly,” put in Zoey.

“Ah,” he said again. He nodded at the latte in her hand. “And the coffee.”

“Yes,” she said. “Let’s not forget the coffee.” They both smiled.

“Somewhere in there,” he said, “you try to scrape off a few minutes’ worth to save. Except most people don’t. So, at the end of the day, there’s nothing left to buy your photo print.”

Despite how dismal that all sounded, Zoey couldn’t help feeling a slight electric thrill ripple through her at those last few words. Your photo print. She nodded, curious to see just where this was all leading.

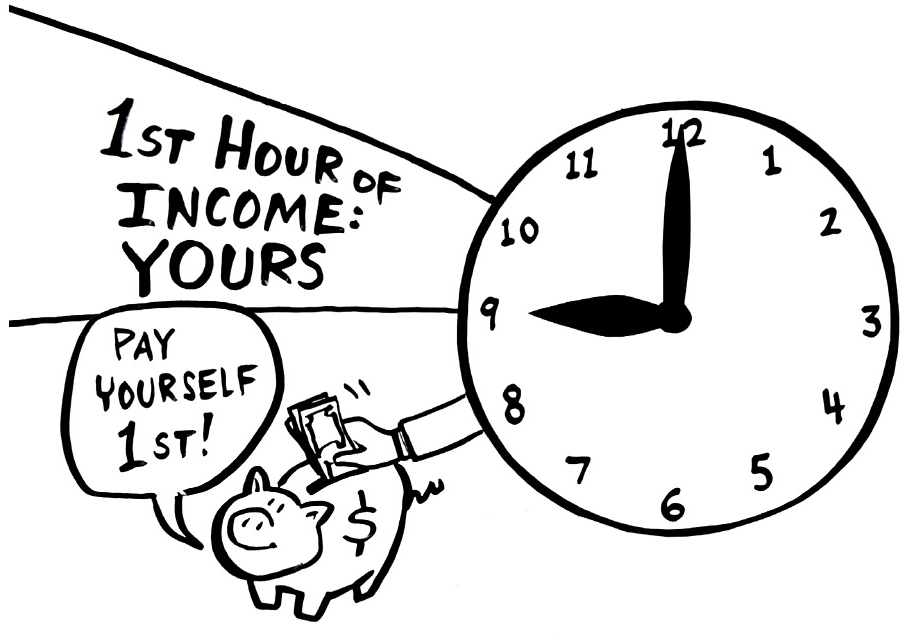

“All right, so I said three secrets, right? Here’s secret number one.”

He turned to a fresh blank page and wrote quickly in long, sweeping strokes:

“Pay yourself first,” repeated Zoey, nodding to herself. “Sure.”

“You’ve heard that before?” said Henry.

“I don’t remember where exactly, but yes, it’s a familiar concept.”

“Excellent,” said Henry. “Do you know what it means?”

Zoey was about to say Of course, but instead she paused, then said cautiously, “I . . . think I know what it means.”

Henry smiled and raised his eyebrows. Yes?

“Well,” said Zoey, “when I get paid, the first person I should spend money on is me.” She looked at Henry. “No?”

Henry smiled again. “Close. That’s what most people think it means: when you make money, you should treat yourself first. Buy yourself something nice, something you want.”

“But that’s not it?” said Zoey.

“Not exactly,” said Henry. “What ‘pay yourself first’ means is that the first person who gets paid is you—and you keep that money. In other words: you pay yourself the first hour of each day’s income.”

He turned to another fresh page in his notebook and began making a second sketch:

“When you go to work, you trade your time for money. Why would you work all day, every day,” he said as he sketched, “and not keep at least an hour of that income for yourself? Yet here’s how most people operate: When they’re paid, the first thing they do, after the government takes its slice, is pay their bills and buy stuff. If there’s anything left over—and that’s a big if—then they save something to keep for themselves. Maybe. In other words, they pay everyone else first, and themselves last. If at all.

“That’s why so many people work eight, nine, ten hours a day, week after week, month after month, for decades, an average of 90,000 hours over a lifetime—ninety thousand!—and at the end of the ride they get off and discover that they have nothing to show for it. That they’ve just spent their whole lives building someone else’s wealth, but not their own.”

Zoey was silent for a moment. Was that what her parents had done?

“Wow,” she said.

“Wow, indeed,” Henry agreed.

After another brief silence, Zoey said, “So, how is it supposed to work?”

Henry regarded her thoughtfully, then said, “When you were a kid, did you ever save your quarters in a jar? To save up for something you wanted to buy?”

In fact, Zoey had done exactly that—not as a kid but as an eighteen-year-old, freshly arrived in New York City to start college. All that summer she’d saved every dollar bill she could scrounge, and after three months she’d bought a bicycle so she could fully explore her new neighborhood. Which had amazed her, because she was normally terrible with money. She’d tried it other times, too, putting ten-dollar bills or even twenty-dollar bills in a jar on her kitchen counter for this purpose or that, but had never reached her goal. Something always came up, and she ended up raiding the jar. She still had that bike, though.

“Well, it’s the same thing here,” Henry said. “Only instead of putting quarters in a jar, you put your dollars into a ‘pay yourself first’ account. A retirement account, technically speaking.”

“Like a 401 whatever,” she said.

“Exactly,” said Henry. “A 401(k).”

Zoey’s company had a 401(k) plan; she remembered being told about it when she started working there. She’d gotten mailings and emails about it and kept meaning to sit down and go through them.

“The idea behind a 401(k) is simple,” said Henry. “Every time you earn a paycheck, you set aside a portion of it—say, 10 percent—first, before it’s taxed. Which totally changes how it compounds.”

“How it compounds,” she repeated. Zoey was fluent when it came to sentences and paragraphs, but math: again, not her thing.

Noting her expression, Henry said, “Here, let me demonstrate.” He reached into his pocket for his wallet, took out a five-dollar bill, and placed it on the table between them.

“Let’s say you took five dollars a day and put it in a jar. How much would you have after a week?”

“Five dollars a day, for a week?” said Zoey. That was easy. “Thirty-five dollars.”

Henry nodded. “Which comes to about $150 per month. Now, let’s say you put that daily five dollars into a pretax account where it earned, say, 10 percent interest per year. Do you know what you’d have at the end of the first year?”

Zoey thought about that. Twelve times $150. “I don’t know, a little more than 1,500?”

Henry nodded. “One thousand eight hundred and eighty-five, to be exact, with the interest included. Now, let’s see what happens to that when you let the power of compound interest take over.”

He slipped a small calculator out of his jacket pocket and began tapping away at it as he jotted down numbers. Who still uses pocket calculators? thought Zoey, smiling to herself. Her barista was definitely old-school.

He paused and looked up at Zoey. “Still saving five dollars a day, where do you think that would go after, say, forty years?”

“I don’t know, maybe . . .” Zoey didn’t see how it could be much more than $50,000, but, just to be safe, she doubled that amount. “A hundred thousand?”

Henry smiled. “Actually, almost ten times that amount.” He turned the little notebook around so Zoey could read what he’d jotted down:

If you saved $5 a day and earned 10% annual interest, you’d wind up with:

1 year |

= |

$1,885 |

2 years |

= |

$3,967 |

5 years |

= |

$11,616 |

10 years |

= |

$30,727 |

15 years |

= |

$62,171 |

30 years |

= |

$339,073 |

40 years |

= |

$948,611 |

Zoey stared at the numbers. “But . . . ,” she stammered. “But that’s nearly a million dollars!”

“It is,” Henry agreed. He slipped another bill out of his pocket, this one a ten, and placed it on top of the five.

“Now let’s say we raised the stakes and paid ourselves ten dollars a day, deposited into our pretax account. Let’s see where that goes after forty years:

If you saved $10 a day and earned 10% annual interest, you’d wind up with:

1 year |

= |

$3,770 |

2 years |

= |

$7,934 |

5 years |

= |

$23,231 |

10 years |

= |

$61,453 |

15 years |

= |

$124,341 |

30 years |

= |

$678,146 |

40 years |

= |

$1,897,224 |

Zoey’s eyes widened as she scanned down the last few rows of numbers and saw the total at the bottom. “Whoa!” she said. “How . . . how did you do that?”

Henry chuckled. “I didn’t do it, Zoey. Mother nature did it. That’s the way nature works. It’s how bacteria multiply. How rumors spread. How wealth is built. Some say it’s the most powerful force in the universe. The miracle of compound interest.”

Zoey stared at his little chart. How was that possible?

“Just ten dollars a day . . . !” she murmured.

“Just ten dollars a day,” Henry agreed. “But ten dollars a day can change your life. Because, make no mistake about it, Zoey: the action itself may seem small, even insignificant—the quarter in the jar, the ten dollars a day—but the decision to do it?” He smiled. “Might be the most important decision you’ll ever make.”

Zoey heard Barbara’s voice in her head, saying, Well, then. Do something about it.

“Now, let me give you another example,” said Henry. “One that’s more to the point. How old are you now?” Before she could reply, he added, “I know a gentleman never asks, but this is for the sake of science. And your secret’s safe with me.”

“Well, if it’s for science, then,” Zoey deadpanned. “Twenty-seven.”

“Perfect,” said Henry. “So, let’s just say you earn $1,000 a week—even I am discreet enough not to ask you how much you actually earn.” Zoey laughed. In fact, that was pretty close to her actual gross pay. “That would be $200 a day,” Henry continued. “Here’s a good rule of thumb: Keep your first hour’s worth of each day’s pay. An hour a day, in other words, of paying yourself first.

“Most people don’t even come close. The average American saves less than 4 percent of what they earn. In other words, most of us work barely twenty minutes for ourselves. And one in five saves nothing at all—that is, they pay themselves zero.”

“Ouch,” murmured Zoey. That was her, all right. Total savings: nothing at all.

“Assuming you work an eight-hour day,” Henry continued, “let’s say we set aside the first hour of each day’s pay for Zoey to pay Zoey. That would be”—he cocked his head as he did the calculation—“$25 a day, or $125 per week. Times fifty-two weeks, that comes out to $6,500 over the course of a year—nearly $6,800, when you add in the interest.”

He started writing out another chart, tapping on his tiny calculator intermittently as he went.

Zoey felt her pulse quicken as she watched the numbers unfold from Henry’s pencil.

If you saved $125 a week (or $25 per workday) and earned 10% annual interest, you’d wind up with:

1 year |

= |

$6,798 |

2 years |

= |

$14,308 |

5 years |

= |

$41,893 |

10 years |

= |

$110,821 |

15 years |

= |

$224,228 |

30 years |

= |

$1,222,924 |

40 years |

= |

$3,421,327 |

When he finished, he quietly set the pencil down and sat back on his stool, waiting.

Zoey sat stunned, staring at the numbers. Over three million dollars. From one hour a day.

Henry glanced at his wristwatch. “It’s getting on,” he said quietly. “You probably need to run.”

With a start, Zoey looked at her phone and leapt to her feet. “Omigosh, I really do,” she said.

“Here,” said Henry, slipping off his stool. “I’ll walk you to the door.”

As they headed toward the front, Zoey said, “It seems so . . . I don’t know. Too simple.”

“It is simple,” Henry replied. “That’s why it works. It’s usually the simplest ideas that change people’s lives, not the complicated ones.”

“Like your ten dollars a day,” she said.

He nodded toward the latte in her hand and smiled again. “Like your coffee drink. Your latte factor.”

“Right,” she said as they reached the front door. “My latte factor.” She had not the slightest idea what that was supposed to mean. “Well, thank you,” she said. “That was most . . . educational.” She reached out to shake his hand.

“Uh-huh,” he said, reading the doubt in her face. He held on to her hand for an extra moment and peered at her. “Zoey,” he said softly, “forget the numbers for the moment. What matters is what’s behind the numbers. When you pay yourself first, what you’re really doing is putting yourself first.”

Zoey frowned. She couldn’t help it: she heard her mother’s voice in her head saying, Put others first, Zoey, always put others first.

Henry gave a small nod. “I know: kind of goes against everything you’ve been taught, right? Nice people don’t put themselves first. Good people think of others first. That what you were thinking?”

“Something like that,” Zoey admitted.

He nodded. “And of course that’s all quite true. A focus on service to others is the defining trait that makes us civilized human beings. But life is paradox, and sometimes the only way you can serve others is to put yourself first. You know what I mean by that?”

“To be honest,” said Zoey, “I don’t.”

“You know that speech they always give on airplanes, when you’re about to take off? About how, in the event there’s a problem, you should put on your own oxygen mask first and then take care of the children? It sounds backwards. You’d think they’d tell you to take care of the kids first, right? But no. Because if you pass out, you’re not going to be any good to anyone. You see?”

“I . . . think so,” said Zoey.

Still holding her hand, Henry placed his other hand on top of hers. “Here’s what I believe, Zoey. I believe that each one of us was put here on this earth, in this life, to do something, something special. Something no one else can do. And most of us aren’t doing it—because we’re too busy paying everyone else first.”

Riding the L train to work, Zoey thought about what Henry had said. I believe each one of us was put here to do something special. And most of us aren’t doing it.

Did she believe that?