Investing in a tax-deferred account can make a huge difference!

Difference: $1,083,503

Thursday morning was bitter cold outside, and despite wrapping her coat tightly around herself, Zoey felt the chill reach into her bones as she fast-walked against the wind. Even so, when she reached the entrance to Helena’s Coffee, she hesitated. Jeffrey’s words were still echoing in her head. She didn’t want to buy into his cynical slant on things . . . but he had some valid points, didn’t he? Maybe she should just walk on by and go to work.

She took a breath, pulled the door open, and stepped inside.

She found Henry sitting at his high-top table in the corner, talking with a tall man who might’ve been a gentleman cowboy from central casting: string tie, pressed white shirt, dark jeans, snakeskin cowboy boots, and a weathered face that looked like a contour map of the Sierra Nevadas.

It was curious, she thought as she waited in line for her latte, how Henry commandeered that corner table, as if it were his official station. It occurred to her for the first time that maybe he wasn’t just a barista; maybe he was the morning-shift floor manager. But hadn’t Barbara said he was a barista?

“Good morning, Zoey,” said Henry when he saw her approach with her latte. “Let me introduce you to my friend. Baron’s in the energy business.”

“Ben Dawson,” the man said, shaking her hand, “but my friends all call me Baron. And my enemies are all back in Oklahoma, so who cares what they call me?”

“Pleased to meet you, Baron. Zoey Daniels.” Zoey shook his hand. Where Henry’s handshake felt like a fine canvas, Baron’s felt like buffalo hide. “I hope I’m not interrupting,” she added.

“Not at all,” said Henry, and he gestured toward an empty stool. “Please. Zoey’s a lover of fine photography,” he said to Baron as she drew the stool up to the table.

“Henry’s been sharing his thoughts on perspective and wealth,” said Zoey.

Baron’s eyebrows shot up into his forehead. He gave a slow, solemn nod and said, “Aha.” Then: “Three secrets? Pay yourself first?”

“Exactly,” said Zoey. “Getting rich on ten dollars a day.” She grinned.

Baron’s eyebrows shot up again. “Ahh-ha,” he said gravely. He turned to Henry. “You fillin’ that poor thing’s head with your nonsense, coffee-boy?”

Henry smiled and leaned in toward Baron. “She’s already rich,” he said confidentially. “She just doesn’t know it yet.” He glanced back at Zoey and winked.

“Ah,” she said. “Well, that’s a relief.”

Baron chuckled.

Henry cocked his head and looked at her thoughtfully. “Though you do have a question.”

Several, thought Zoey. “Seriously, I do,” she said. “So I’m not great with structure when it comes to money, as I said. The whole dollar-in-the-jar thing.” Henry nodded. “Honestly, I have a hard enough time sticking to an exercise plan. I get the whole ‘pay yourself first’ idea. But I just don’t see myself having the discipline to keep doing that, week after week, for months, let alone years.”

Henry nodded. “You probably wouldn’t. Which is why there’s a second secret.” He paused slightly for dramatic effect, then said: “I imagine you’ve been taught about the virtue of budgets.”

Oh, boy, thought Zoey, here we go. Zoey hated budgets. She knew it wasn’t rational, but something in her rebelled at the very idea of it.

“Budgets!” trumpeted Baron. “Ha! First thing you do with a budget is you take the whole idea, virtue an’ all, and toss it in the trash with the rest of the garbage!”

Zoey stifled a burst of laughter. Yes! A kindred spirit!

“Budgets!” Baron repeated. “What hogwash.” The man was on a roll. He leaned in toward Zoey. “You hate budgets, am I right?” She nodded. “Course you do. Everyone does. Well, not everyone, now: there’s such things as people who naturally do well with budgets. Rare, precious creatures, like unicorns. We need those folks, and we give ’em important jobs. Where I work, that’s the CFO. He loves budgets. Probably keeps one under his pillow at night. The rest of us mortals? We hate the things, hate ’em like poison.”

Zoey was looking forward to seeing how Henry was going to handle that outburst and still remain his ever-polite barista self.

Henry just nodded. “He’s right, of course.”

Zoey stared at him. “Excuse me?”

“Oh, budgets work well enough for corporations and other organizations,” Henry continued. “But not so well for individuals. If you have to write a check every week to make your savings plan work, it just won’t happen. It’s not a measure of character, Zoey. It’s human nature. The idea of a personal budget sounds sensible, in theory, but in the real world, it doesn’t work.”

“Know why that is?” put in Baron.

Zoey cleared her throat and said, “No. Why?”

“ ’Cause they’re no fun, that’s why!” Baron had hijacked the conversation once again. “They’re like diets: easy to start and dang near impossible to stick with. Makin’ up this list of where all your money oughta go, and tryin’ to squeeze your life into all these little pigeonhole categories—it’s a nightmare. Goes against our nature!”

Henry smiled. “True enough. Which is more or less where I was going with that: no budget is going to make you, ‘pay yourself first,’ no matter how logical or responsible it may seem. There’s only one way to make that happen.”

He turned to his notebook and flipped back to the page he’d written on the day before, where underneath the words “Pay Yourself First” he now added a second line in his long, sweeping hand:

2) Don’t Budget—Make It Automatic.

“If you have to write a check every week, or keep going online to make regular deposits, sooner or later the thing will unravel. You just won’t do it.

“Zoey, let me ask you: Do you consider yourself a busy person?”

“Ha!” said Zoey. “Understatement of the year.”

Henry nodded. “Of course you’re busy. Everyone is. I’m guessing that the last thing you need is some extra task piled on—like drawing up a budget and then keeping track of it week after week. The truth is, you probably just wouldn’t do it.”

Zoey certainly couldn’t argue with that.

“The only solution,” said Henry, “is to take the day-to-day decision out of your hands, by setting up a simple, automatic system that will run by itself in the unseen background. So it takes zero discipline, zero self-control, zero willpower. Just set it up and let it run.”

“Can’t spend what ain’t in your pocket,” put in Baron.

“Exactly,” said Henry. “That’s the beauty of the automatic system. Every two weeks, or every month, or however often you’re paid, you set it up with your employer so that your 401(k) contribution automatically comes off the top—which happens before withholding comes out for taxes, by the way—and the balance of your paycheck is automatically deposited into your checking account. That’s it.”

“It’s that simple?” said Zoey.

“It has to be that simple. If it isn’t, you won’t do it. And if you don’t make it automatic, it just won’t happen.”

“ ‘Make it automatic,’ ” she murmured, tapping the words into her phone.

Baron spoke up again. “The government had this figured out years ago. Up till World War II, all us good Americans collected our paychecks in full and didn’t pay Uncle Sam his chunk till the following year. Problem was, all us good Americans didn’t plan so well. We didn’t budget.” He chuckled. “So they tried spending a bunch on campaigns to teach us how to budget so we could pay our taxes. And son of a gun—that didn’t work, either! So Uncle Sam said, ‘The heck with it,’ and set up a simple system that pulled out his chunk—”

“Automatically,” added Henry.

“Automatically,” Baron repeated, “before it even reached our undisciplined little hands. And whaddaya know: it worked. Every time we earned a dollar, Uncle Sam got paid first.”

“And then corporate America got into the game,” said Henry. “Do you belong to a gym, Zoey?”

As a matter of fact, she did, treadmills and all.

“Does the gym automatically take a membership fee from your checking account every month?”

She nodded. “They set it up the day I joined.”

“Course they did!” put in Baron. “So do most companies these days. ’Cause it works!”

“And that’s the second secret,” said Henry. “You simply do the same thing for yourself. In fact, the government provided a specific pathway for you to do exactly that—before they take out their share for taxes.”

“My 401(k),” murmured Zoey.

“Your 401(k),” Henry agreed. “A pretax retirement account. There are other types, too—IRA, self-employment plan (SEP) IRA, and so forth—and other countries have the same idea. They go by different names, with different details, but they all boil down to the same thing: a place where you can pay yourself first, automatically, before your income is taxed.”

“And with that,” Baron said as he pushed back his stool and got to his feet, “if you’ll excuse me, ladies and gents, I think it’s time to partake in some of Helena’s finest. Anything for you, ma’am?”

Zoey smiled. “I’m fine, thanks.” When was the last time she heard someone say “ma’am”?

“Quite the character, your friend,” said Zoey as they both watched Baron head up toward the front to go foraging for food.

“Oh, yes,” said Henry. “Resilient, too. Used to be in the oil business, but that industry went through some tough times. When he moved to New York, he found a job here with a company working in the energy sector, dealing in renewables: wind, solar, and some new technologies, too. Fascinating. Hydrogen, waste heat conversion . . .” He put a rough twang in his voice and dropped it an octave. “ ‘Stuff my daddy wouldn’t reckonize.’ ”

Zoey laughed. His Baron impression was excellent.

“Welcome to the future,” Henry added. He looked at Zoey. “But you’ve still got a question.”

“Actually,” said Zoey, “it’s a few questions, I guess. If that’s okay?”

“Shoot.”

Okay, here goes, she thought. Zoey did not want to be rude, but she didn’t see any way to get clarity on Jeffrey’s objections without just coming out and asking.

“So, yesterday,” she began. Henry nodded. “You talked about setting aside some of your income and putting it into an account that gets 10 percent a year.” Henry nodded again. “I’m . . . wondering about that. I have a friend who says you can’t really get that kind of return anymore. That it’s a thing of the past.”

Henry smiled. “I understand. A lot of people are skeptical about that. But the reality of it is, since 1926, the first year they started collecting reliable data, the stock market has shown an average annual gain of over 10 percent. Sure, the economy booms and busts, we have bull markets and bear markets. How much you actually earn in any given year depends on the year and what you invest in. But when you get past all the drama and look at the big picture, it all averages out. Markets go up, then down, and then up again—always. There’s never been a market that went down but didn’t ultimately go up again.

“After the Great Recession of 2008, people said the days of making money in the market were over. Guess what the market has done since then?”

“Gone up?” said Zoey.

Henry smiled. “With an average annual gain of more than 10 percent.”

“Wow,” said Zoey.

“Historically,” added Henry, “even the most boring, conservative portfolio of stocks and bonds would have earned you a solid 8 percent. But the exact number isn’t the point, Zoey. The point is to save and let that number compound for you.”

“Okay.” Zoey thought back to her conversation with Jeffrey again. “But I still get taxed when I take it out, right? So I end up being taxed either way.”

“True enough,” Henry replied. “But if you keep that dollar for yourself now, instead of giving thirty cents of it to the government, then you have more to invest now. Time and the miracle of compound interest have more to work with, so it’s going to grow a good deal more. And you don’t have to pay taxes on it as it grows each year.

“Here,” he said as he turned to another blank sheet in his notebook. “Let me show you.”

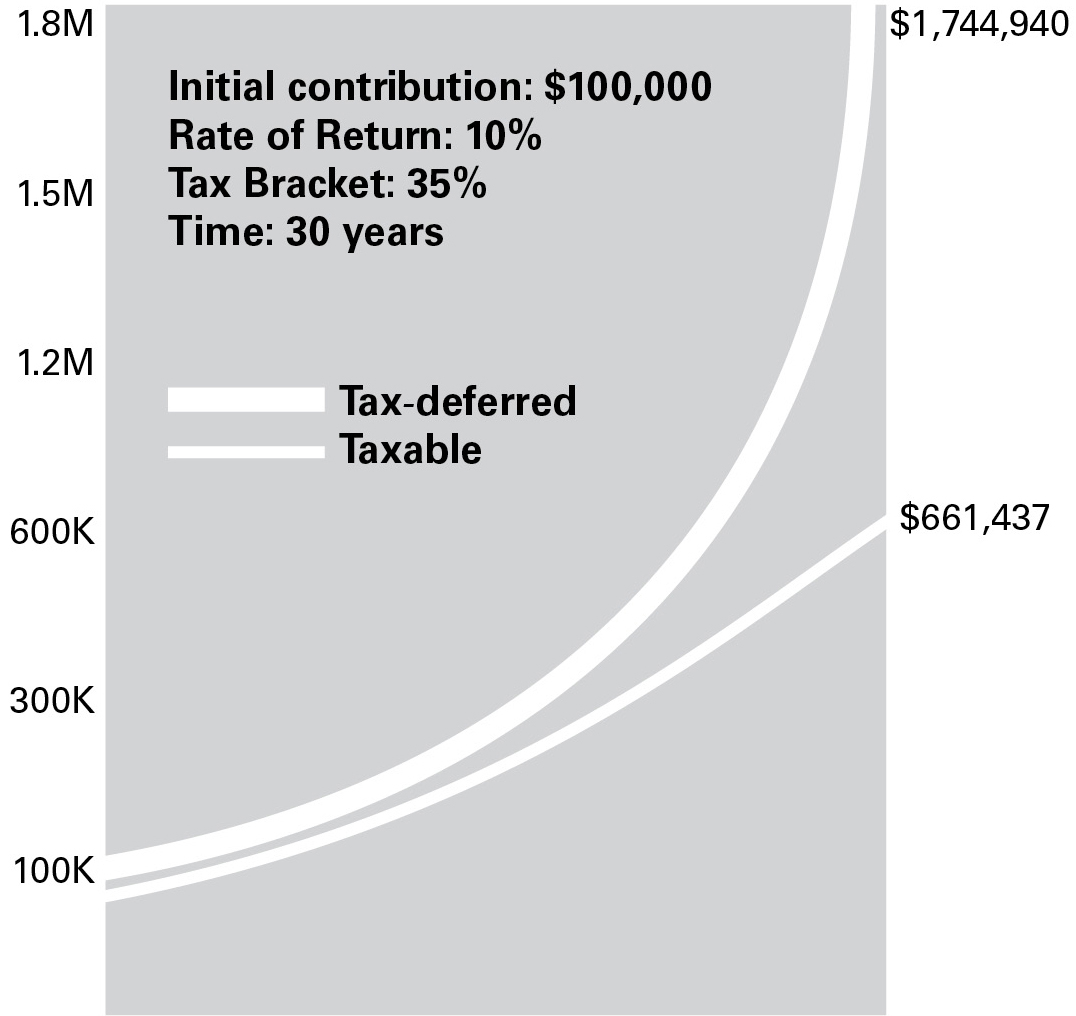

He began sketching a graph with some numbers and two long curved lines.

A burst of raucous laughter erupted from the front of the shop. Zoey looked up and saw that Baron was regaling the four other customers in line with some story or other. They were all chuckling with him. So was the hipster behind the counter.

Ignoring the scene Baron was making, Henry began explaining his graph.

“Let’s say you put $100,000 into an investment that pays an annual return of 10 percent; in thirty years it will have grown to about $661,000. But if you put that same hundred grand into a tax-deferred account over the same amount of time, it would come to more than $1.7 million. Nearly triple, in other words.”

Zoey didn’t follow all the math in every detail, but she got the picture, all right. “Nearly triple” was clear enough.

“When it isn’t taxed while you’re growing it,” added Henry, “money grows not just faster but exponentially faster. So who cares if you pay taxes on it later, after you’ve done the growing? If you really want to pay the taxes first, you can start a Roth IRA, where your money grows tax-free forever—after you pay taxes on it going in. But if I have a choice between keeping all the money in my account now and paying the government later, versus giving them part of it now? I don’t know about you, but I’d rather keep it all now.”

Zoey was still staring at the chart. “Why doesn’t everyone know this stuff?”

Henry shrugged. “That’s an excellent question. Sometimes the simplest truths are the easiest to overlook. Or to dismiss as . . . well, as too simple. Not dramatic enough.

“You know that expression about how you eat an elephant?”

Zoey took a sip of her latte and nodded. “One bite at a time.”

“Well, that’s exactly how you build a fortune. One dollar at a time. But here’s how most people think you get rich: you win the lottery. You get lucky, and a friend gives you a tip on a new cryptocurrency or great tech stock no one else knows about yet.”

Zoey thought of Jeffrey and his surefire plan to launch the next Instagram.

“Or you get an inheritance. A piano falls on that accident-prone great-aunt.” (Good memory, Zoey thought with a smile.) “Or maybe you find buried treasure in your backyard. And you know what they all have in common? They’re all dressed-up versions of the same vague fruitless hope: Someday my ship will come in.

“In the movies, sure. But in reality?” He shook his head. “For each person who pulls a winning ticket, there are millions standing in line waiting for the ticket that never comes. Perched on the shore looking out at sea, hoping for that loaded ship to arrive. It’s a fairy tale, Zoey—a way of comforting ourselves with a fantasy, perhaps so that we don’t have to face the day-to-day reality of our situation.”

“Yikes,” she said. “You make it sound so bleak.”

“Well, it is bleak. Bleak is exactly how it works out for a great number of people. It’s the financial expression of what Thoreau called ‘lives of quiet desperation.’

“But here’s the thing, Zoey: it doesn’t have to be. The truth is your ship is right here, right under your feet. You’re standing on the deck. It has already set sail. And you’re the captain.

“The question is, what course have you set? And what course do you want to set?”

“Here we go,” Baron’s voice boomed as he rejoined them and set a plate on their little table with two thick slices of some kind of cake, followed by a coffee cup, which he placed in front of Zoey. “Zucchini bread,” he said. “Brought you another latte, Zoey. Just in case.”

Henry looked up and saw that the line in front now stretched clear to the front door. He got to his feet.

“Will you excuse me?” he said, and he went up front to step behind the counter.

Baron turned back to the little tray he’d set down on the table next to them and now brought out a tiny ceramic cup of something hot. “And a fresh hot espresso, neat, for—”