Alex nodded to herself as she hurried down the hill sniffing the bands of honeysuckle fragrance that came in gentle waves on the warm breeze. “Rockets. Space food. Wait till Chuck hears,” she muttered, quickening her step. “She said to come back.” The dog wagged and trotted on ahead.

Chuck was Alex’s main friend. She had other friends, but when Chuck was around she skipped them because his adventures were more interesting. He liked to show off for her. She knew he was dangerous. None of the neighbors let their kids play with him. Those that did often got hurt. Chuck got hurt a lot too, but he didn’t seem to mind—it was like he wanted to go to the edge of everything.

“Dinner in ten minutes, dear,” her mother called as Alex walked into the house. Her mother was a small, quick, straight-standing figure. The gold chain with her heart pills capsule hung around her neck. Dinner smelled good. Pot roast.

Alex’s mother kept their home as tidy as Ebbs’s but with a lot more stuff, mostly old family things she’d brought back from Europe. She had gone to school in Germany and learned languages. Now she worked at home translating German songs. Alex liked to listen when her mother played the phonograph and sang the strange words.

Before Alex could eat she had to pass John’s tests. It was part of his tutoring deal with their mother. Every Sunday noon before dinner Alex had to define and spell five vocabulary words and work some math problems from her schoolbook. She resented John’s getting paid for ordering her around, but her grades were getting better. John said he was doing it so she wouldn’t end up dumb like Chuck.

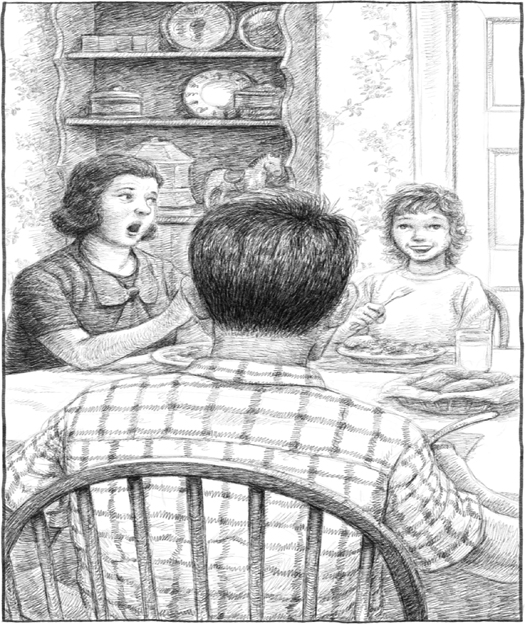

“In the development there’s this lady named Ebbs,” Alex announced as they sat down. “She’s got pictures of airplanes and rockets all over her walls, says she makes food space pilots will eat—seaweed tubes they’ll boil up into spaghetti and smear with chemicals—if they can swallow since they’ll be eating upside down, and if their ears haven’t blown out without pressure and gravity.”

“Easy, Alley,” Chuck said, laughing as his sister gobbled her dinner. “She’s putting you on.”

“No!” Alex exclaimed through a mouthful. “She told me a lot about her work, and she’s got pictures. She’s in one of them, in uniform with a bunch of men standing around this big rocket they captured. She says since a gallon of water weighs five pounds they can’t take up much, so they’re gonna drink recycled made out of their pee.…”

“Alexis! Please!” her mother said. “That’s vulgar.”

Alex went on undaunted. “And before she started making the space pilots’ food she made energy bars for bomber pilots. She gave me one. It’s got coffee and raisins in it. She said she invented it for the long-distance pilots who’d be up in the air for hours and hours and had to stay sharp, but I had to spit it out.”

John made a noise. Alex was delighted; she’d got to him. She was always fighting for a place in the conversation.

“Why she’s telling you this stuff, I can’t imagine,” John said, “but if she’s for real and you ever see her again find out why we want to go up there in the first place. It’s empty! The stories we hear about looking for life? It’s a boondoggle to get money for the airplane makers!”

“Empty?” Chuck said with a snort. “Some night pull your nose out of your books and look up!”

“Boys!” their mother said firmly. “Let’s not argue about Alexis’s new friend. I think it’s nice that she’s met someone in the development, and I’m sure Mrs. Ebbs is glad to have met someone from the established part of the neighborhood—”

“Ebbs is just Ebbs,” Alex interrupted. “Or Captain Ebbs. There’s no Mister around.”

John rolled his eyes.

“That’s not all,” Alex said excitedly. “She told me how to train for taking off in spaceflight.”

She leaned back in her chair and pantomimed. “See, you put a brick on your belly like this and push down real hard and grunt—unnnnhhhh!” she bellowed as loud as she could. Jeep lurched up with a woof.

“Alexis!” her mother scolded as Chuck laughed and her dad struggled to look serious.

“She got it from this German rocket scientist she helped capture—that and the experiment he did to see if our brains would turn to puddings on liftoff. He got some mice and tied them up in little hammocks and turned his bicycle upside down and fitted the hammocks around the rear wheel. He started cranking the pedals as hard as he could to get the wheel spinning fast enough to stress the mice like a pilot taking off, but he hadn’t balanced them right, and one of the mice shot free and splattered against the wall and made a big mess.”

“Alexis!” her mother exclaimed. “That’s enough.”

“Oh, it was OK, Mother. I mean, not for the mouse, but for the experiment. Ebbs said he got a fresh mouse, balanced the wheel more carefully, and started cranking again. When he stopped and checked, the mice were all alive, so Ebbs says that proves we can stay alive getting free of gravity. The guy she helped capture is named von Braun. She says he’s gonna be the Christopher Columbus of space.”

“A Nazi!” John snorted.

“Sounds like you’ve met someone really interesting,” her dad said as John glowered.

“Yeah,” said Alex. “She says she had to ride roller coasters a lot to learn what would keep the space pilots from puking in flight.”

“Alexis!”

“It’s tomato juice!” Alex giggled, getting up from the table to start clearing. “Tomato juice keeps you from puking.”