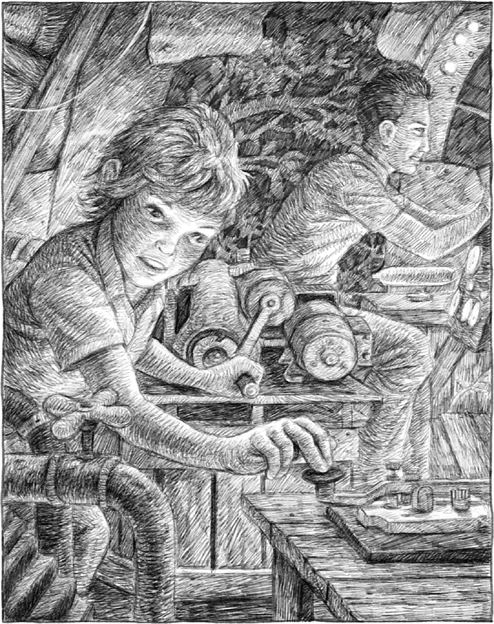

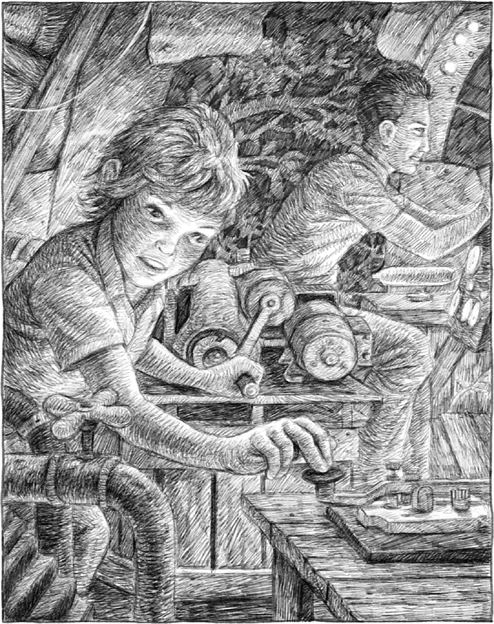

That night in the Moon Station’s cockpit Alex cranked the hand generator. Red lights glowed over switches and dials, the pretend radar gave off a pale green light, the big vacuum tubes glowed pink with what looked like tiny buildings inside. Chuck was navigating. Suddenly he called to Alex, “Pilot to copilot: sighting craft approaching fast fifteen degrees off starboard.” It was the flashing lights from the WTOP radio tower. “Adjust thrust,” he ordered as Alex turned valves. “Quick, signal identity and greeting in Code Alpha.”

“Roger,” Alex snapped in her official voice as she cranked the generator with one hand and tapped out a message on the Morse code key. She looked out of the Station’s nose cone. The red and green signal lights were pulsing as she tapped dot dash dot dot dot dash dash.

“Message received,” Chuck announced. “Prepare to dock. Mission done.”

They leaned back for their evening chat.

“Sounds like huffduff to me,” Chuck said when Alex told him about Ebbs’s space colony plan.

“It isn’t. Ebbs says she knows the people who build rockets and she’s been to some island near here where they track asteroids on radar.”

“Wallops?” Chuck asked, sitting up. “She knows about the radar dishes on Wallops?”

“Yeah. That’s it. Wallops.”

“Huh!” said Chuck. “If she’s for real she must have a really high security clearance. What I don’t get, though, is why she’s got all this time for you.”

“Dad says it’s the plants. He says working with plants you make friends and it doesn’t matter how old you are or if you’re man or woman. Anyway, do we ever hear voices from space?”

“Maybe in some of the static we get on the radio,” Chuck replied. “Rosy says the new radar is going to pinpoint where it’s coming from. That’s why I want to get in on it, and it sounds like maybe you’ve met somebody who can help me.”

“I guess,” Alex muttered. She’d told herself she wasn’t going to tell Chuck much about Ebbs because Ebbs was her find, and if Ebbs met Chuck, maybe she wouldn’t pay attention to her anymore, and maybe Chuck wouldn’t either. Alex had always felt possessive about Chuck, and now she felt possessive about Ebbs too. “Because they’re interesting,” she told herself. “They’re hybrids.” That was the word her dad used to describe his rarest plants.

Later, in her bedroom, Alex felt for the space rock in her pocket. She hadn’t shown it to Chuck because it was private, a symbol of her special bond with Ebbs—Ebbs had given her something she’d prized. Alex had gotten lots of presents, but they’d all been bought things or hand-me-downs, nothing the giver really wanted to keep.

Alex’s room was in the front of the house. Her shelves were filled with books, stuffed animals, junk, her box of crystals. A large chunk of petrified wood was on the corner of the lowest shelf. Every night she saw a head in the shadow where streetlight hit it. She knew she was too old to take it for real or be scared of it, but she was, so every night she’d bargain with the shadow to leave her alone.

Tonight she didn’t notice the head. She watched the sky for space rocks. Suddenly a bright greenish light flashed through the stars. She held her breath and felt for the smooth square she’d put under her pillow. Ebbs said it was going more than a hundred feet a second. What if there’s some kid standing outside in Australia?

She watched the sky. There were no more shooting stars. She looked around her room. It was as if she were seeing it for the first time. She got up and took down the pictures of the dancing insect musicians. When she got back in bed she stared at her shelves. “Ebbs doesn’t keep things she isn’t using,” she murmured, getting up again.

Jeep lay on the bed watching as Alex cleared her shelves until the only things left were The Greek Myths and the crystals. “Shipshape”—that’s what Ebbs would say. “Just the essentials and everything shipshape.”

A painting of Icarus was on the book’s cover. As Alex stared, the sun melted his wings of gold, the feathers went free, Icarus fell horror-stricken toward the blue-green sea. She heard his cry, but his father was out of sight and the ship in the distance was too far away to help—even if the sailors had seen something amazing, a winged boy falling out of the sky.

Just then Jeep shot under the bed like a mole to his hole. Alex’s mother was coming up the stairs. “Time to tuck in, dear,” she said, breathing hard as Alex slid under the covers. If her mother noticed anything changed, she didn’t say. She didn’t come up often—only when she felt strong enough to give her daughter a good-night kiss. Tonight, though, was different. She had something on her mind.

“You’re almost twelve, Alexis,” she said as she sat down on the bed, “so I think it’s time you spent less time in that Moon Station and quit climbing up trees where nobody can see you, coming home scratched and bruised. And your hair,” she continued as she smoothed what was left of it, “your lovely hair all chopped away. Oh my.”

Alex gently pushed her mother’s hand away. She felt a cautious tenderness for her, as if her mother were a delicate china cup.

“It’s time for you to act more ladylike, Alexis, pay more attention to your schoolwork, start music lessons, and dress more carefully. Skirts. The neighbors say you’re becoming a tomboy.”

“I’m not,” Alex protested, “but I don’t want to do that other stuff. I want to learn radio and flying and do space work.”

“No, Alexis,” her mother said. “What you’re talking about is not for girls.”

Alex lurched away. “What do you mean? Mrs. King had us read about this woman who flew alone across the Atlantic. They called Earhart a tomboy too, but she wasn’t. Ebbs says all kinds of women are pilots now. She says the first space pilots will be women because they weigh less. Chuck and I are going to do it together.”

Her mother got up wearily, shaking her head. “Charles,” she corrected. “His proper name is Charles.” She bent over and kissed Alex on the top of her head. “Good night, dear. That woman pilot you’re reading about crashed somewhere in the Pacific. We don’t want that to happen to you.”