The next afternoon, Chuck told Alex about going to the Flying School. “Nobody was around,” he said. “The hangar was empty. I waited for the instructor. When he taxied up in the Piper Cub, I went over and talked to him. He told me the sound in the plane’s radio goes in and out. I said I was a student of radio, I’d fix it in exchange for a lesson. I’m going to take my tester and tools over tomorrow. If I fix it he says he’ll take me up.

“He let me sit in the cockpit and work the yoke and everything. I could do a takeoff; you aim into the wind to do it. The big thing is, you’ve got to get the wind going over the wing fast enough to lift off. There’s an indicator that shows it. Coming down is easy—you just glide in like those balsa gliders we fool around with sometimes. You want to watch? Want to go over to the airport tomorrow instead of school?”

“Sure,” said Alex, thinking about the new name on her door. Flight was flight. Ebbs said VB got started flying small planes.

“Meet me in front of Doc’s Variety so they won’t know,” Chuck said.

Jeep was waiting with Alex when Chuck drove up. “There’s an observation deck,” he said excitedly. “While I’m fixing the radio you can watch flights taking off and landing. Maybe he’ll let you come out and sit in the cockpit with me.”

Chuck drove fast, talking about taking off and flying, gesturing as they raced to the airport. When they got there he left Alex and Jeep on the deck and ran over to the flight school’s dingy-looking Quonset hut. The Piper Cub was parked nearby.

Chuck yelled something at the hangar door, then went to the plane and climbed in to work on the radio. A little while later he vaulted out, looked around, turned the prop slowly, waved to Alex, then swung himself back in. Alex got a bad feeling in her stomach as Chuck started working the Cub’s ailerons and swinging the tail. Suddenly he was out of the cockpit again checking the wheel chocks. He flipped the prop. There was smoke. The engine caught.

“Hey, Chuck! Don’t do it!” Alex screamed as he kicked away the chocks and pitched himself back in. The plane started to roll. Alex could hardly breathe.

The flight instructor rushed out yelling and waving his arms as the plane wobbled off, the sun catching it like a golden toy. Icarus, Alex thought as the plane straightened out and sped down the runway.

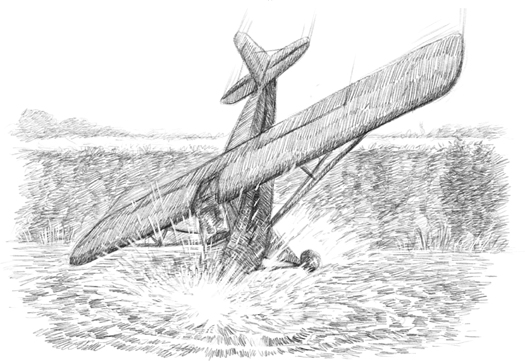

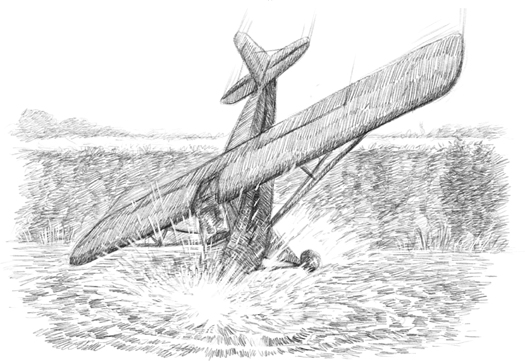

Toward the end of the runway it slowed and lurched to the left, the wing scraping the pavement as Chuck tried to turn the plane around. He was going too fast. The plane skidded, ran through a patch of grass, bounced over a mound of earth, and splashed into the river.

For a long moment there was a silence like sand falling, then pandemonium. Sirens went off. An air horn sounded stunning blasts. Alex raced down the stairs with Jeep close behind and ran as fast as she could to the end of the strip. By the time she got to the wreck emergency vehicles were on their way. They brought Chuck up, muddy and stumbling. Nobody noticed Alex until Chuck saw her and waved.

“I’m OK, Alley!” he yelled, trying to look brave. He pantomimed holding a telephone and mouthed, “Ebbs.”

“Who is he? Who are you?” an official demanded.

Suddenly Alex was cool and professional. “I’m his sister,” she said. “He’s a student of flying. He’s learning it like Doctor von Braun. Please help me. I need a telephone.”

She ended up in somebody’s office. The man got Ebbs on the line. As soon as Alex heard her friend’s voice her self-control dissolved. She began to sob so hard she could barely get out the news that Chuck had crashed a plane. “He—yes—he’s OK. He had a deal with the flying school pilot. For fixing his radio he was going to get a lesson, but, but he tried to take off himself and it went into the river. I told the people here he was just being like VB.”

“I’ll be right over,” Ebbs said. “Have you called your father?”

“No.”

An hour later they were all crowded in the airport security office: Chuck in a corner looking sullen; the officer in charge and some of his people; Alex and Jeep; and the flight instructor, who was sputtering, “He stole it. He stole my airplane and wrecked it.” That was when Ebbs walked in.

She looked around, then stared hard at the officer in charge. He recognized her. He mouthed the word “paperclip.”

She nodded.

Alex noticed and glanced at Chuck. He had noticed too.

“I’m representing the boy’s parents,” she said.

“This is a serious matter,” the officer began. “He maybe thinks it was a prank, but it’s really what the owner says—theft—not to mention violation of all sorts of federal flight regulations.”

Ebbs spoke up in her army voice. “Perhaps there was a misunderstanding.” She turned to the flight instructor. “My young friend here was doing a radio repair on your aircraft when it happened, right? He was in the plane with your permission, correct? In exchange for his work he was to get a lesson—yes?”

The man tried to speak, his lips working like a goldfish, but Ebbs kept talking and turned back to the officer in charge.

“It could be attempted theft,” she continued in a respectful tone, “but it could be he was trying to give himself the lesson he’d earned: taxi down a little, brake, turn, and taxi back. But he got going too fast, couldn’t stop and turn, so he ran it into the river. Looked at that way, it’s reckless and careless—but not criminal.”

The officer shook his head. “It’s a whole lot more than reckless and careless, Cap … ah, ma’am—an unlicensed person running an aircraft out on an active runway without tower clearance or anything—and what do you do about this man’s aircraft?”

“We’ll take care of the repairs,” Ebbs replied evenly. “They’ve already pulled it out. I checked it before I came in. There’s damage to the wing and some struts and the wheel assembly, but nothing that can’t be fixed. We’ll cover it.”

The airport security people talked things over. “We could charge you with criminal trespass,” the chief announced, glaring at Chuck, “but we’re not going to. We’ll give you the benefit of the doubt under the, ah, circumstances,” he said, glancing at Ebbs, “provided you satisfy the owner that you will pay for everything.”

“Done,” said Ebbs, nodding to the instructor, who was already holding her check. “Right?”

When it was over and they were standing outside, Ebbs turned to Chuck, her eyes narrowed, her voice low. “Mister, if you were in the army under my command, starting now you’d be in jail doing real hard duty.”

Riding home, Chuck was blithe. “You know what, Alley? I really was trying to take off. I just wasn’t going fast enough. The airspeed indicator was still showing red when I got to the end of the runway. I tried to work the Cub’s brakes as I turned, but things were happening so fast I couldn’t. I wasn’t afraid, though. I had this great taste in my mouth—like when I swing on that fraying grapevine over the ravine and I’m hanging at the end of the pitch and I don’t know whether I’m going to snap and crash or make it back—and either way’s OK.”