The first day out, cramped and hungry in my hiding, I fed myself on what I imagined I’d see and do in Rome, but then the ship began to pitch so hard and the sailing got so rough it drove me out from my hiding.

When they discovered me a stowaway, and worst of all a Protestant, they threw me overboard, the sailors swearing God would drown them all if I stayed on board. Not a voice was raised to save me as they told their rosaries loud to be spared my screams as they pitched me in like another Jonah.

When I hit the water I counted myself dead, but then my luck, which always comes to me in threes, came on in the form of a pirate ship that had been tracking my pilgrims just over the horizon. They picked me up as a slave to sell. When I told them what sort of ship their quarry was, they let it go, not out of mercy but because pilgrim luggage wasn’t worth their trouble.

I was with them all that summer learning their pirate tricks of surprise, our faces made up fierce and reckless like actors, screaming and roaring as we boarded to drown our own terror.

My tutor was a jagged three-inch piece of mirror glass I could use as a weapon if need be. I studied in it for hours to cast fire from my eyes so you’d know that once you took me on, if you didn’t kill me I was going to do my best to kill you. I was small but quick, and I could wrestle better than anybody. The scars I earned in that trade soon made me look older than my years.

The night we landed at Marseille I dropped off the side naked as a fish, my boots and clothes in a tarred bag at my side. I swam to shore with a gold coin in my cheek and a sailor’s knife in my teeth.

I hung around the port, watchful lest my old shipmates see me and try to get me back, juggling and cartwheeling in the dark and poorer places to pick up food and news until I snared what I needed: stale bread and word that the King of Hungary had work for soldiers. I set out to the northeast. Having now my scars and pirate knowledge, I hired on to fight the Turks attacking Vienna.

I was some years in that business, learning the work of a journeyman soldier and teaching my fellows the tricks of fireworks for signaling and terrorizing until, to show off my bravery to my employer, I volunteered for single combat against the Turks’ champion.

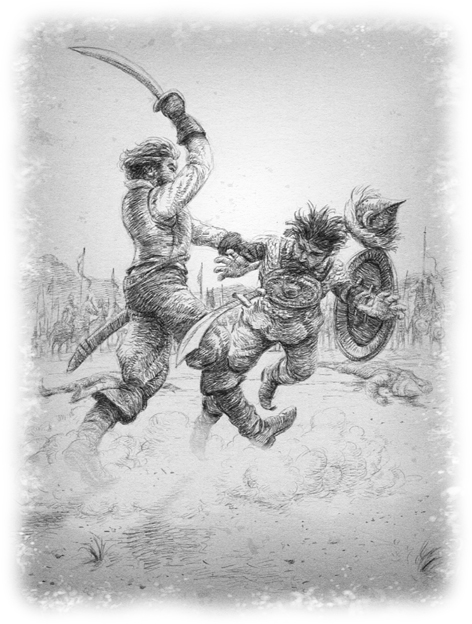

We fought in an open field in sight of both armies. I killed my man with a lucky stab to the eye, but then the Turks put forward a second champion saying I hadn’t fought fair, as if any Turk ever does. No choice and no matter, I dispatched the second one as well by cartwheeling around him to chop at his heel strings. As he fell my slash sent his neck gushing blood like a bilge pump. Then the Turks called forth their third champion. This one was timider, a slow, cautious dancer as he sought to avoid me. I tripped him with a wrestling trick—a quick side step—and took his head too for my pile. They had many more champions, I’m sure, but no more volunteers.

For this service the Hungarian king awarded me the title Captain and a coat of arms featuring my three Turks’ heads. Now I, a poor man’s son, was a Captain in the Austrian Imperial Guard with a coat of arms and a chamois leather bag of gold as well.

I counted that adventure my third piece of luck, but that bag of gold and all that’s passed through my hands since I’ve never liked as much as some men do because I seem to smell the stench of dead flesh on every piece. Gold remembers; it is the one metal that never tarnishes.

There I was, by reputation the terror of Turks who swarmed before us, but then my luck turned as it always has for me: three bads following three goods. In what was meant to be a minor skirmish I went down with a gash deep in my leg. That night I lay faint and cold, bleeding to death when the pickers found me—the folks who come out after battles to strip the dead for clothing and treasure. By what I wore they recognized I was no common soldier, so they staunched my wound and cleaned me up for ransom, but unfortunate for them and me they stripped and shaved me so bare that no one believed I had any significance at all, so I ended up bald as an egg, sold as a common slave in the Constantinople market.

Constantinople, that magic-sounding place I’d dreamed of in my dull merchant’s shop back in England: it was now all mine to see, but it didn’t look so fine through a prisoner’s eyes.

The pasha who bought me riveted a heavy iron ring around my neck with an outsticking spike shaped like a sickle to grab me by and haul me about. He used me badly. I was the lowest of the low, but I kept up my spirits by thinking of nothing but learning the Turk language.

One afternoon my pasha came alone to where I was working by myself threshing grain. He spat on me for being a Christian. In a black rage I hurled my threshing bat into his gut. He went down doubled. My next blow did for his head.

I stripped him, put on his Turk clothes and knapsack, buried his body in straw and was off on his horse with the heavy spiked iron still around my neck.

As I rode off I remembered other times I’d escaped in another man’s clothes and wondered if someday someone would slip into mine to make his escape smelling my stink of fear and feeling the last of my own damp warmth.

I rode for my life. Wherever one road crossed another there were arrows with pictures: to Persia, a black man with white spots; to China, a sun; to Russia, a cross.

For sixteen days I rode for Russia, afraid of being identified as a runaway by that iron around my neck with its spike sticking out, my shaved head and my ignorance of the land and language. For food I played the beggar, juggling, cartwheeling, and grinning like an idiot until I reached the Russian garrison on the River Don, where my newly grown red hair and freckled skin caught the eye of a Russian lady. She had my iron removed.

For a time the lady Calamata befriended me. When she finally turned me out it was with a piece of news and a jewel to remember her by, a diamond. Before she told me her news she taught me how to test if a diamond be true: a true one pressed against ice will melt it. Glass will not, nor will any other jewel.

Her news was of a means to get back to England: a group of English merchants had come to the czar at Moscow seeking permission to trade English woolens for sables and timber. Sure that I knew the Russian tongue better than anyone else in that group and certain that the czar was after warmer stuff than cloaks and blankets, she sent me to Moscow to make myself useful. I went in the guise of a priest. The high-collared shirt hid the scar of the iron ring I’d worn.

Her hunch paid off. It was how to make guns and gunpowder the czar was after, and I knew that business from my pirate time. So you see now how my hands are still stained black from kneading sulfur, saltpeter, and charcoal with old urine to make fire signals, smoke bombs, lightning, and blasts to blow down walls and forts.

In disguise I finally made it back to England. I was twenty-five when I got home, scarred for life from that ring—a body mark that was to fascinate my Native American captors, as did my black-veined hands. To my former neighbors’ surprise I now had a title, a coat of arms, a sable collar to hide my mark, and some gold, not that they sneered at me any the less. New titles and new gold did not count as much with them as old.