The next morning Alex helped her father weed. Working with dirt and plants made her feel better. She told her dad about getting caught stealing. He already knew. “Hold to your pledge, Alex,” he said. “Stealing leads to a world of trouble.”

That afternoon Ebbs said the weekend weather looked promising, so they should go sailing on Saturday. “Old clothes,” she ordered, “the oldest you’ve got, and your most beat-up sneakers. If your dad’s got any old white shirts he can spare and some old hats, bring those along too. And dog food. I’ve got everything else.”

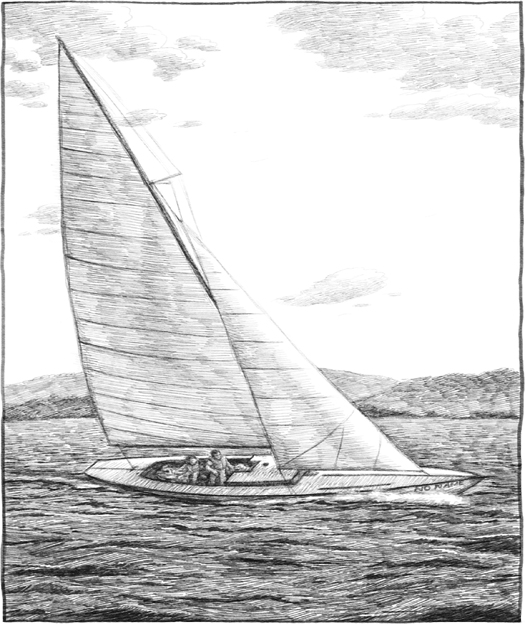

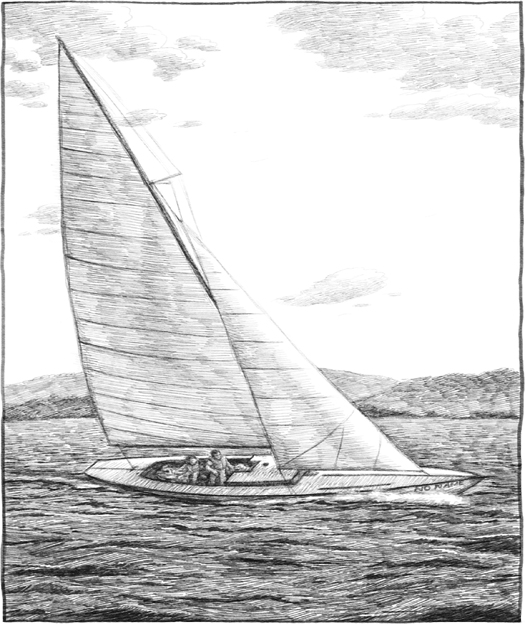

On Saturday morning Alex, Chuck, and Jeep rode with Ebbs down to the river to see the No Name. Ebbs fumbled and bumped into things on shore, but on board her moves were exact. She handed out heavy kapok life vests that made them all look like red blocks. For Jeep she’d rigged a harness belowdecks, a sort of hammock that held him dangling like a carcass, his paws barely touching the bilge boards. He grumped and grunted as she fitted him into it. It offended his dignity to ride that way, but Ebbs was firm. She was firm about everything. Jeep could have escaped. Ebbs left it loose enough for him to get out if they capsized, but he felt it his duty to stick with them.

“Shipshape is more than housekeeping,” Ebbs explained as she showed them how everything had its special place. “It’s survival. We’re on our own out there, nobody can help us; we might as well be a mile down in a cave. Something goes wrong, it’s on us to fix it—replace a broken halyard, stitch up a torn sail, jury-rig a snapped mast. We’ve got to be ready for anything, so you’ve gotta learn the four basic sailors’ knots: reef, square, bowline, and half hitch. They’re not easy. It took me a lot of practice to get them right, but like my father said, ‘Patience is never wasted.’ If I can manage ’em with my clumsy fingers, you can too.”

Ebbs pushed them off from the dock and ordered Chuck to raise the mainsail. A slight breeze swelled it and they were off. Alex was surprised how just that wisp of wind could make the heavy boat heel as it glided them along.

Ebbs showed Alex how to set the anchors and check the tide chart. “And pump,” she added, reaching down for a black tube the length of her arm with a handle on top. “You’ll stick the bottom end into the bilge and pump it as dry as you can. In weather and rough water we’ll take turns.”

The current and the outgoing tide carried the No Name along, but they were going faster than the water, as Ebbs proved by tossing out a chip that they shot past. The river had a strong smell, something between old salad and wet dog.

“Smith mapped all this,” Ebbs said, one hand on the tiller, the other pointing to the shore. “The chart he made shows that point over there. He knew it would prove useful. It’s where barrels of tobacco the later colonists called Virginia gold got loaded on ships to London. Helps you understand the connectedness of water, how it links up everywhere. Stick your hand into the Potomac here and you’re connecting with London docks, or whatever port you name.”

Suddenly the river wasn’t empty. A cruise ship came toward them heading up to Washington. Ebbs shifted the mainsail, tacking and working the tiller to steer them away. They waved, the ship’s captain tooted, and soon they were dancing in its wake, Jeep swinging like a clock pendulum in his harness. He gave Alex a baleful look as she laughed and rocked. Chuck stayed forward, leaning against the mast, silent.

“Mount Vernon,” Ebbs announced as they glided soundlessly past a long green sloping meadow that led up to a large white mansion with columns. “George Washington’s plantation. There’s his tobacco pier. Story goes, he once tried to skip a silver dollar across the river from that pier.”

Alex scrunched up her face to judge the distance. She shook her head. “Bet it wasn’t his dollar.”

“Check the tell tail,” Ebbs ordered.

“The what?” Alex asked.

“The wind indicator. That strand of horsehair tied to the mainstay.”

Alex looked. The tell tail had begun to droop. Gradually the wind stilled to nothing.

Ebbs turned to Alex. “Looks like we’ll be drifting for a while, so tell me, do you know what Quo vadis means?”

Alex shook her head. It sounded like something John would ask.

“It’s Latin for ‘Where are you going?’ ” Ebbs explained. “Tell me where you’re going.”

“Doctor von Braun told me I’m going to fly in space someday. He said maybe I’d go with him.”

“Great!” Ebbs exclaimed. “But how are you going to get ready? What are you going to study? What’s your work going to be? The test pilots I work with—the people who are going to be our astronauts—they didn’t train to be passengers. They’re medical doctors, physicists, chemists, biologists. You’ve told me where you’re going—now I want to know what you’re going to do to get yourself there. Chuck’s talking about doing electronics, but right now he’s luffing, which is a sailing term meaning his sails are flapping idle so he’s not going anywhere. I’ll get to him. What I want to know from you is, how are you going to get to liftoff? What are you interested in?”

“Rockets, space, radio …”

“Right,” said Ebbs. “So what are you going to do with your life?”

Alex squirmed. It felt like she should have nailed that down by now.

When the wind picked up again they came about and started back upriver. Suddenly Ebbs winched up the keel, handed Alex the tiller, and pointed to a pier. “Get us there,” she ordered.

Alex swung the tiller, but the boat didn’t respond. She tried fishtailing it. Nothing happened. The No Name turned like a leaf in the current and started drifting downstream at a pretty good clip.

“It’s like you,” Ebbs said. “Drifting with no plan. Having no life plan is like having no keel, no control over where you’re going. You don’t have to hold to it, but it’s high time you both start mapping out where you’re going in life, what you might do. You can always change course later on, but it’s good to have a starting point—something to measure your progress against. So here’s a project to start you both off,” she announced as she let the keel down and brought the boat about again.

“I need deckhands for a cruise—one-way down the Potomac and out into the Chesapeake to Tangier Island, where I’ve got a friend who will put us up. It’s my vacation. I want to spend it on the No Name, but I can’t do it without crew. If you two say OK, and your parents agree after they come and check things out—your mother especially, since she’s the sailor—your pay will be a dollar a day each. I’ll get you back home before school starts. As we go, we’ll make like we’re Captain Smith’s crew, mapping the shoreline as we follow the chart he made and searching like he did for the lost Roanoke colonists I’ll tell you about. We’ll carry all our food. I’ve got some great new recipes going.”

Chuck caught Alex’s eye and raised his eyebrows.

“I saw that,” Ebbs said with a laugh as she got out the navigation chart. “As we go along we’ll tuck in here and there for ice-cream cones, bread, and suchlike, but you guys will be my food testers. I’ve been living on my new stuff for months now, and I’m not wasting away, am I?”

Ebbs rolled out a much-thumbed sea chart and pointed to the upper left corner. “Here’s where we are, Washington,” she said. As the heavy paper curled tightly over her left hand she pointed down to its far right. “And here’s where we’re going. You’re going to mark our progress, Alex, so hold the chart,” she said as she reached for a pair of dividers that looked like heavy tweezers with sharp points at the ends. “You’ll use these to work out our distances,” Ebbs explained. “You spread them against the miles scale to set the distance, then swing them point to point down our course. We’ll follow Smith’s course from here at Washington downriver to the bay. As a crow flies it’s about a hundred and thirty miles to our jump-off at Smith Point.

“From there out to Tangier it’s about twenty miles straight across open water, but of course we’ll be zigging and zagging to keep the wind, so it’s going to be up to you, Alex, to keep us on course following the buoys against the map and working the compass.”

On the map Tangier looked tiny and far away, barely a gray-brown dot against the bay’s blue green. “It’s the top of an undersea hill,” Ebbs explained. “That’s all any island is, a mountaintop sticking up out of the water.

“From Washington down to Smith Point it’ll take us five to ten days, depending on the wind and tides. Then to the island, a day—with any luck. If we don’t make it in one we’ll anchor and sleep on board. It’ll be a little tight, but we’ll manage. You can sleep down below—there’s room, but it gets stuffy—or I’ll wrap you in tarps and tie you down on deck so you won’t roll off in your sleep.”

Alex didn’t like the idea of getting tied down. She and Jeep moved around at night, but sleeping in the space under the deck didn’t sound like much of an alternative.

“What’s the island like?” she asked.

“Flat. One church. Three miles long, a mile across. It’s close enough to Wallops that you can hear the roar when they do a test firing. If they launch we’ll get to see the flare.”

“Great!” Chuck exclaimed. “Any chance they’ll do one when we’re there?”

“Launch times are classified,” Ebbs said, “but I hear from my friend Pete they’re getting ready.”