It was first light. Alex was dreaming and drifting, half-asleep, half-awake, when the sound of a hummingbird working a dark orange trumpet vine blossom just overhead snapped her alert. It sounded like a giant wasp. The bird was the size of her thumb, its beak stitching fast among the flowers like a long black needle, its wings invisible. It never stopped to rest. It was so fast, so slight and magical it made her smile. A squirrel began dropping chips of the green pinecone he was gnawing. The sky was streaked with pink like the inside of a shell. Low-flying birds skimmed over water that looked like it had been combed in two directions at once. Dew had caught in the spiders’ webs in the grass, making them glow like pewter weavings.

Crows calling and crying roused Jeep. His muzzle was swollen, his nose parched. He’d had a bad night, dozing and whimpering, too pained even to push his way to the foot of Alex’s bag, where he usually slept.

Alex wet a cloth from her canteen and bathed the dog’s nose. Ebbs produced a can of chicken broth. Alex spooned it into Jeep’s mouth sip by sip.

Ebbs hustled them through breakfast, each one mixing his own bowl of cereal with hot water. The cereal was the blend of dried grains called Meals for Millions that Ebbs had fed the refugees in Europe. The formula was one part cereal to six parts boiling water, then you shook on powdered milk. Busy tending to Jeep, Alex forgot the one cereal to six waters proportion. She mixed hers one to two parts, like oatmeal. There was tepid coffee with cocoa and sweetened condensed milk; then they waded out to the boat, Ebbs carrying Jeep paws up like he was a baby. “Next landfall, Tangier Island!” Ebbs called as Alex hauled up the anchors.

Alex had never been at sea before. Looking out over the open water, she couldn’t see anything. She shivered with what she told herself was excitement.

Once they were under way, the morning sun glared off the water. The three sailors looked like desert travelers with smears of charcoal under their eyes and the hats and long-sleeved shirts Ebbs made them wear. Jeep groaned and nursed his hurt in his hammock under the deck.

Alex began to feel thirsty.

The water’s emptiness made her uneasy. She wished she had something to do, like climbing a tree. She figured if you’re not in the stern holding the tiller and running things, sailing’s a waste of time—unless, of course, that’s the only way to get where you’re going. She decided the sailing life wasn’t for her. She looked down at Jeep and nodded. The dog wagged feebly.

Between sessions of leaning out when Ebbs ordered it, Alex pumped and marked their course on the chart from seamark to seamark. Then she glanced at the barometer mounted on the cockpit cowling. “Hey, Ebbs!” she shouted. “The barometer’s falling.”

“Right!” Ebbs called back, glancing at the sky. “Weather’s coming.”

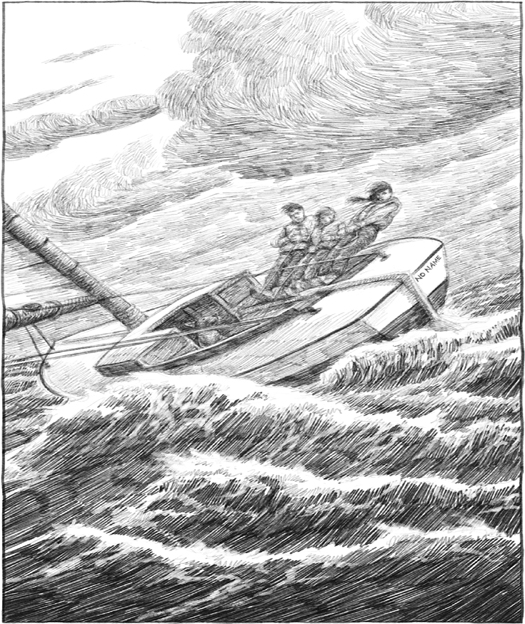

Over the next hour the wind changed quarters, opposing now as strongly as it had favored them before. Ebbs tacked this way and that, battling the onrush, spume swishing over the bow and gunnels as she worked the lurching winds to their advantage. They were all leaning out a lot now. It was a rough ride under fast-moving clouds, first mares’ tails, then the slower, ominous low cumulus.

Chuck called over. “Hey, Alley! How far from Tangier to Wallops?”

Ebbs shook her head. “Can’t do it, Chuck. Can’t sail there in this. Anyway, Wallops is off-limits. No civilian boat can land there.”

“OK, so never mind sailing to it,” Chuck countered, “but as the crow flies, straight line from Tangier to Wallops, Alley, how far?”

Alex studied the map and worked the dividers. “Maybe thirty miles,” she answered. “Seventeen over water, then maybe twelve across the peninsula, over the bridge to Chincoteague, then to the channel next to Wallops. But I don’t see any bridge to Wallops.”

“There isn’t one,” Ebbs snapped. “Put it out of your mind, Chuck. For security they keep it remote. The engineers and army folk live there in Quonset huts with no weekends off. You fly in or go by boat. No one is allowed to visit without prior authorization. It’s a military installation—they’re testing missile rockets there, so they’re real edgy about spies and saboteurs. They’ve got armed guards all over the place.”

Chuck frowned. “So we’ll be watching the launch from thirty miles away? Heck! You can’t see anything from that far, and anyway there’ll be land humped up between us and them, so we won’t see the tracking radar at all.”

“If you’re watching at the moment of liftoff you’ll see the flame,” Ebbs said, “maybe even get a glimpse of the rocket itself before you hear it. It’s like a big rolling thunderclap.”

“Yeah, but the tracking stuff,” Chuck pressed, “the radar—we won’t be able to see that.”

“No.”

“What does it look like?”

“Two saucers angled up, each as big across as a man,” Ebbs said. “They’re called Dopplers. They measure how fast the rocket’s rising and track its direction. A technician stands beside each dish aiming it with a hand crank as the craft rises, if it rises. It’s dangerous work. If the rocket fails on liftoff the technicians risk getting hurt. Some have.”

Alex handed Chuck the map. He was fidgety as he studied it. “We could get closer, Ebbs,” he said. “A lot closer. Like, we could go over to the peninsula and put in at Crisfield.”

“Could,” said Ebbs, “but Tangier’s where we’re headed.”

“How do folks get to the mainland from Tangier?” Chuck asked.

“Most take the mail boat,” Ebbs said.

“Does it go every day?” Chuck asked.

“Every day except Sunday. It’s the island’s lifeline, brings in news, batteries, gasoline, everything.”

“Today’s Saturday,” Chuck said. “The launch is maybe tomorrow?”

“Maybe,” said Ebbs. “I hear it might be the new rocket. They don’t make it public, but they always cut back the mainland’s power beforehand. When I called Pete from the marina to say we were heading out, he said Crisfield Harbor had gone dark to send extra out to Wallops. I know what you’re thinking, Chuck, but put it out of your mind. Remember our deal: no more dumb moves. I’m working on our plan. Don’t mess it up.”