The channel looked to be a mile across at least.

“I’m hungry,” Alex announced.

Mosquitoes settled on them like a cloud.

They were standing on a patch of dried mud patterned like cracked glaze. Jeep was snuffling around a sodden hulk half-sunk in water. Chuck waved his hands like windshield wipers to keep the bugs off his face.

“So, Alley, how do we get over there?”

“There’s boats at that place we passed on the road coming here,” she said. “We’ll rent one—tell ’em we’re going fishing.”

As they crunched back up the white-shelled track Chuck felt in his pockets for money. He fingered up a dime and a quarter. “This is it, Alley—all I’ve got.”

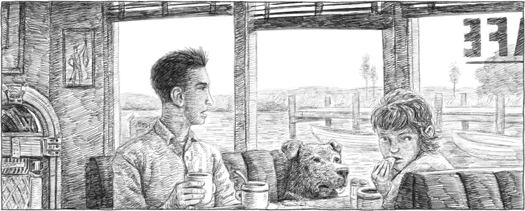

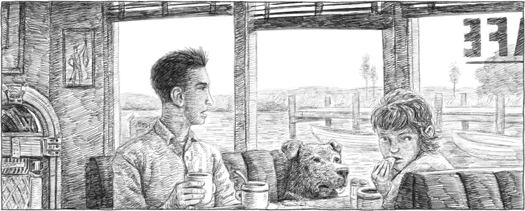

It was dim inside Cousin Marge’s. It smelled of cigarettes, stale beer, fish, and frying. They had enough for two mugs of soup and a coffee. The hard round crackers and horseradish paste on the table were free, so they filled up on those as Chuck emptied the sugar bowl into the cup of coffee he shared with Alex. Soon as they finished the coffee the cream went into the mug for Jeep. The dog worked the mug like a hummingbird going at a honeysuckle blossom: not a splash, not a drop wasted.

The jukebox was going in the corner. Two couples sat in separate booths. Three men were hunched together over their beers in another. By studying their shoes and boots Alex worked out that the men had come in the boats outside, the couples had come in the cars.

The men ordered another round. They were just warming up.

“We’ll have to borrow from them, Chuck,” Alex said, indicating with her head the men in the booth.

Chuck paid and they went out, sauntering like tourists down the dock. The skiff at the far end had an outboard. So did the newer-looking dory, but that one could be seen from Marge’s window.

“The skiff, right?” Alex said as they moved down the dock.

Chuck swung into it smooth and easy like he owned it. Alex jumped in lightly, dragged in the dog, then lifted the painter from the piling and pushed off hard as Chuck primed the motor, put the throttle to low, and set the choke. Three pulls and it caught, spitting and spluttering. Acting like they were in no hurry, Chuck eased off the choke until he’d brought the motor to a steady purr, then powered it up to a roar and headed out across the channel. They didn’t look back. They couldn’t hear anything over the motor.

Chuck didn’t aim for the lights. He pointed them toward the far end of the island, the boat going flapaflapaflap as she pounded across the waves. There was fishing gear at his feet and a gray felt hat like their dad’s, only worn and stained. Alex put it on. “Disguise,” she said.

The oars stowed against the gunwales were banged up, the handles worn with use. None of the fishing gear was fancy sportsman’s stuff. Alex felt bad about taking from a workingman, but then she figured whoever owned the boat would get it back soon one way or another—they weren’t going far.

Just then the engine staggered a few beats and died.

Chuck checked the tank and shook his head at Alex. “Dry.”

The shore was about a block away now. They were close enough to make out trees, branches, and the tall fence festooned with red, white, and blue signs.

Thinking jellyfish, Alex asked, “Do we swim it?”

Chuck shoved an oar into the water. Halfway in it stuck in mud.

“No, it’s not deep. We can walk it. Keep your shoes on; the shells are sharp.”

Chuck jumped in, gasping at the cold shock. “The bottom’s firm enough. Your turn!”

Twisting around, keeping her hands on the gunnels, Alex swung herself in, panting and blowing as the cold hit. With a big drenching splash Jeep dived in beside her.

Alex kept the hat on.

Jeep swam on before them. Chuck half towed Alex until it was shallow enough for her to clamber on her own, mud and muck sucking at her shoes. They met up with no jellyfish.

There was a narrow margin of marsh weed and ooze, then the tall Cyclone fence with strands of barbed wire flecked with blades strung in swirls on spokes leaning out along the top.

Alex figured she and Chuck could make it over somehow, but what about Jeep? They couldn’t leave him. They were stuck: no way in and no way to get back. The boat had drifted out of sight by now. Ebbs will kill me, Alex thought. I was supposed to say no to stuff like this.

Every fifty feet were red warning signs on the fence: DANGER! NO TRESPASSING. HIGH SECURITY AREA. U.S. GOVERNMENT PROPERTY. PENALTY FOR TRESPASSING: FINE AND IMPRISONMENT.

A flat, slow-paced loudspeaker voice droned in the distance, the breeze and water noise blotting out the words.

Near where they stood the fence was humped up over a rock the size of a large wastebasket. High tides and storm wash had loosened it.

Exploring the shoreline they found a heavy piece of driftwood. They dragged it back to the rock, levered the rock aside enough to make a slither hole, pushed Jeep through, then squirmed under themselves.

“Wallops!” Chuck whooped. “We made it! I’ve got that great taste in my mouth, Alley! This is big!”

Their faces were streaked, their bodies covered in greasy, dead-smelling mud.

Jeep shook himself, sending clots of mud and sand flying. Everything except his muzzle was smeared and splattered. The only other unmuddied thing about them was the hat Alex had managed to keep dry and now pulled low over her head.

“Ha!” Chuck exulted. “Wish I had a picture, Alley! So here’s our plan. We’re Captain Smith going to meet the Turks. We’re going to walk toward the lights. When we get close enough to be seen you’re gonna put that hat up on a stick so if they start shooting that’s what they’ll hit first.”

Shooting? Then Alex remembered what Ebbs and TJ had said about security on the island—“armed guards.” She caught her breath. She’d been scared before—caught in her spy tree when a thunderstorm came up, knocked overboard earlier that day—but this was worse: soldiers might be shooting at her?

Chuck doesn’t care, she thought as he kept talking away.

“Then we’re going to start marching like we’re going to a camp inspection: hut-two-three-four, hut-two-three-four, and, and”—he was getting more and more worked up—“and we’re gonna be singing—yeah!—singing! ‘Halls of Montezuma’—singing it as loud as we can. We’re gonna get caught—we want to get caught, OK? But they won’t shoot if we come on like that. When they get us, let me do the talking. It’s gonna be scary, you’re gonna be scared, me too, but whatever they ask or threaten just pretend they’re all standing around in dirty underwear, embarrassed and wishing they could get away. Got it? Once they see you’re a girl we’ll be OK. They’ll never shoot a girl.”

Gonna be scared? Alex thought as she tried to wipe the mud away from her tickling nose. The back of her hand was even muddier than her face. Her knuckle smeared on a clown’s mustache. Underwear? They’ll never shoot a girl?

They started out. Chuck picked up a long stick, forked at the end. “Perfect!” he exclaimed. “When I say to, perch the hat on it so it rides level and hold it up high as a tall man. A decoy!”

Like what T did for Smith, Alex thought. Hope it works again.

“Keep control of Jeep,” Chuck ordered. “Don’t let him get excited and lunge or bark or anything. It’s all a game, right? Play it like a game. We’re gonna see that rocket and the radar!”

It was dark. Lightning bugs flickered. They made their way toward the launch site lights until they came to a long stretch of paving painted with yellow bars. In the darkness they could make out several small airplanes parked off to one side.

“A landing strip!” Chuck said in a hushed voice. “You know what, Alley? Maybe I’ll fly us out of here in one of those after the launch—do a Captain Smith escape!”

It was too dark for Alex to see Chuck’s face, but she knew he meant it.

The loudspeaker was clear now, the voice slow and methodical as it reported the launch protocols: “Procedure thirty-two.” Pause. “Check. Procedure thirty-three.”

Alex was shivering but she wasn’t cold. Jeep rambled and sniffed, marking territory as he went along.

They were skirting a lighted circle now, three sides of it a concrete baffle barrier with a clamshell roof pulled back. Suddenly, coming up on the open side, they could see the rocket. Alex forgot about being scared. She caught her breath. It was beautiful—shinier and more wonderful, more alive than anything in Ebbs’s photographs, even though it was smaller than the V-2 in Ebbs’s picture. The rocket was slender and straight-sided, the latticework gantry hugging it like a mother her child, a flag and USA in vertical black letters on the side, its gleaming white nose. The nose was wreathed in swirls of fog-like mist. The rocket was surrounded by a lot of machines and pipes and men scurrying around. It was like a giant white wasp in its cocoon, trembling, dangerous.

“Liquid oxygen or maybe coolant,” Chuck said softly, pointing at the mist. “Put up the hat.”

The loudspeaker droned on: “Procedure fifty.” Pause. “Check. Procedure fifty-one.”

Off to the right was a low cinder block box with a few small rectangular openings, each the size of a shoebox. “Flight control,” Chuck whispered.

Then: “Look, Alex!” A few yards beyond were the big radar dishes they were looking for—the Dopplers.

“Oh, man,” she sighed, all the air going out of her at once. They were like giant eyes, insect eyes, monster eyes for the towering white wasp.

A uniformed operator stood to one side of the closest radar dish, his hands resting on the aiming wheel he would use to keep the dish focused on the missile as it rose.

Alex couldn’t help it. The hat on the stick began weaving and twitching.

The operator noticed and started yelling.

“Forward, march!” Chuck bawled.

They began moving toward the cinder block box, Chuck marching stiff and formal, Alex stumbling to get in step as Chuck roared out the song, Jeep striding alongside, tail up—

“From the Halls of Montezuma

To the shores of Tripoli

We fight our country’s battles

In the air, on land, and sea …”