TJ’s mother made an omelet with a lot of tomatoes and onions. They all sat around her kitchen table and listened to Chuck and Alex tell about sneaking onto Wallops.

Jeep barked frantically when Alex jumped up and started marching and singing again to show what they’d done. He’d had enough.

“You two are just plum lucky you didn’t get shot,” Mrs. Jester opined. “From all we hear, folks out there are real touchy, but then you don’t exactly look like spies, and I reckon they was too busy to notice much, getting ready for the launch. Guess you brought ’em luck—the last three fizzled.”

Chuck smiled. “I told VB how to fix the rocket.”

“Go on!” TJ said, laughing.

“It’s true,” Alex said. “Chuck told him to cut the line while the rocket sat live on the launchpad, and VB said he’d been thinking the same thing, so that’s what they did.”

TJ’s mother made up beds for Pete and Ebbs. She got out stuff for Chuck and Alex to sleep on the floor in TJ’s room.

“Oh no, no dogs,” she said when Alex asked for some rags for Jeep. “Lie down with dogs, get up with fleas.”

“Then I’m sleeping outside with him,” Alex announced. Mrs. Jester relented.

Alex didn’t stir until she smelled coffee and bacon. Only after she’d pushed all the bedding aside did Jeep move, starting with a languid rolling-over. A great shake followed to clear himself of fleas.

Over breakfast Alex got Ebbs to tell TJ about the T she’d described in her version of Smith’s journal. Ebbs agreed that Alex’s new friend looked a lot like the boy standing beside Smith in the portrait.

After TJ did his tomato run, with Alex helping, TJ took her to see the headstone. It was weathered and lichened over. Alex thought if you didn’t know what you were looking for, it would look like an ordinary stone. The only singular thing about it was how it sort of stood up on end. She couldn’t make out anything until TJ took her hand and guided her finger along the outline of the letter.

After they got back to the bookshop, Ebbs said TJ should come up and see Smith’s portrait as soon as tomato-hauling season was over. She said she’d cover his bus fare and put him up, seeing as how he was likely close to being kin.

“There’s no point our going back to Tangier,” she said. “Pete will take the Captain Sam over. Between Thanksgiving and Christmas we’ll sail the No Name back up to Washington. What’s important now is getting Chuck in a program for VB, so tomorrow morning we’ll catch the bus home.”

It was a little tricky getting Jeep on the bus. Company policy didn’t allow for pets, just service animals, but Chuck made up some story about Jeep’s name and his war service, so they got him aboard.

“Focus is the big thing,” Ebbs told Chuck as they rode north.

“He’s focused when I read aloud to him,” Alex said. “He doesn’t have any problem following then. Maybe if you taught him by talking to him it would work.”

Ebbs looked thoughtful. “Worth a try,” she said.

Alex listened, half dozing, as Chuck and Ebbs talked over their plans. The land outside the bus window flashed by like sheets of colored paper, flat field after flat field, soybeans and corn, sometimes alfalfa, an occasional grain silo, now and then a long chicken shed. Ebbs’s attention was on Chuck now, but it didn’t bother Alex as it had before. She’s getting him going, saving him, she thought, counting the telephone poles. I figured he’d take her over, but she’s taking him over. It’s not all on me anymore. And TJ’s coming!

“We’re going to start with your writing,” Ebbs was saying. “Benjamin Franklin learned to be a good writer because he had to write real slow as he set type in his print shop, one letter at a time. You don’t jump around in your head doing that, so our program for you is going to be Franklin’s making one letter at a time.”

They ate the bag lunches Mrs. Jester had prepared as they skirted water, a finger of the bay Alex remembered from studying the maps. But she didn’t want to check with Ebbs and interrupt her telling Chuck about the program. Alex saw possibilities for herself if she could attend some of the sessions.

“For math we’re gonna start with the basics,” Ebbs was saying. “I’ve got a box of sugar cubes we’re going to work with, so you can see and feel what we’re doing as we stack them and move ’em around, adding, dividing, multiplying. Then we’ll cut a strip of paper into like pieces—fractions. You’re going to see right off how numbers fit together—that they’re really all just bits and pieces you can see and move around. You said with radio if you can see it you can do it. It’ll be the same with math.”

Chuck looked dubious.

“You’re gonna like it,” Ebbs insisted. “I’m going to get the music of math into your head. It’s all rhythm, getting the numbers to dance. They want to dance. Once you start hearing their music you’ll be charmed. First thing in the morning for half an hour before I go to work you’re going to come up to my house for a talking math lesson like Alex suggested. Then when I get home we’ll do a half-hour talking review. In between times, you’re going to go to that new vocational school in town. I called. You’re enrolled: an early Christmas present!”

“Holy cow, Ebbs!”

“Hold on,” she said. “I’m not done yet. You know why they hang the carrot in front of the donkey’s nose?”

“Yeah, to keep him going.”

“That’s part of it. The other part is to keep him from snatching at grass by the side of the road—getting diverted.” She paused.

“So what’s my carrot?” Chuck asked.

“Flight lessons. Saturdays we’ll go out to the field at Rockville. A friend of mine from Paperclip days has an old Piper Cub—the two-seater J-type they trained army pilots on during the war. You do your part during the week—with no escapades—you get a carrot. Deal?”

“What about me?” Alex demanded. “There’s gotta be something in all this for me.”

“Like what?” Ebbs asked.

“Flight lessons.”

“They don’t do them for kids,” Chuck said.

“I’m not a kid anymore,” Alex said, glowering. “I’m an astronaut in training. VB said so.”

“I’ll talk to my friend,” Ebbs said. “We’ll work out something.”

That night, at home around the dinner table, Chuck asked, “Why is she doing all this for us?”

“Because you and Alex have become her family,” Stuart replied. “She loves you.”

Chuck started going up to Ebbs’s every morning for Focus and Drill and every afternoon for review. He told Alex how Ebbs was talking him through numbers and holding his hand to shape his letters. Alex felt left out. Ebbs had no time for her now, and she and Chuck spent less and less time in the Moon Station. Alex saw what was coming.

The big consolation was that every Saturday she went with Ebbs and Chuck out to Rockville for a flying lesson. She had to sit on a pillow to manage the controls, and she couldn’t solo, but she was learning to fly. The instructor said there was no question about it, she’d get her junior license the day she turned fourteen. Just like VB, Alex thought.

A week before Labor Day, Ebbs sent TJ money for a bus ticket to Washington. She took off work so she and Alex could meet his bus and drive him around Washington, showing him the Capitol high on its hill, the White House sitting in its great expanse of green lawn, the Lincoln Memorial out by the river. TJ was handsomer than Alex had remembered, and taller. He limped a little. “New shoes,” he explained when Alex asked why. “Mom made me get ’em.”

The thing he most wanted to see was the Moon Station, so as soon as they got to Alex’s, she sent him up the slats. He almost fell when the screecher went off. That weekend TJ and Alex spent most of their time up there. Jeep insisted on going up with them. After being on the No Name, he was steady on his feet in the Station now.

By Christmas, Chuck was beginning to manage the basic design diagrams and calculations at the vocational school, and now even John could read what he wrote in blocky capital letters. Their parents invited Ebbs for Christmas dinner. She came with a letter. “Just came this afternoon, Special Delivery!” she announced. “VB’s agreed to give Chuck a chance. He says they’ve got a school at Fort Bliss that can pick up from where he is in his vocational schoolwork. If Chuck will enlist in the army and passes all their tests—which I’m sure he can do—VB will take him.”

“Hey! Hurray!” Alex shouted, even as she fought to hold herself in.

In order to enlist, Chuck had to present a copy of his birth certificate. Stuart stopped at the bank on the way home from work to get it out of the safe-deposit box. He arrived home with two stamped documents. The whole family stood around when Chuck unfolded the top paper. It was in German. The only word Alex recognized was “Carlus.” The names and surnames for both Mutter and Vater—mother and father—were strange.

Chuck’s face twisted. “I knew it,” he whispered.

“What does it mean?” Alex asked.

Her mother took a deep breath and explained. “After I came home and married your father I heard from a cousin in Germany about an infant whose parents—her dearest friends—had both just died in a typhus outbreak. My cousin could not keep this child. She begged me to come and take him. Germany was in chaos then, close to revolution, so we went and collected him. That second paper is the important one, Charles. It’s your adoption certificate. There you see your full name: Charles Stuart Hart.”

“I knew it,” Chuck said again. Alex couldn’t tell whether he was sad or angry.

“You knew from what I told you when I gave you the ring,” his mother said. “When I gave it to you I said it was old and had come down to you from your family in Europe. I hinted and waited for you to ask, but you didn’t. It seemed to me you didn’t want to know more right then.”

Chuck shook his head.

“You’re the same brother I had yesterday,” Alex said. “It’s not like they just hung a name on you like you told TJ. They rescued you because they wanted you—they wanted you to make it, like Ebbs and VB and me.”

“And me!” John said.

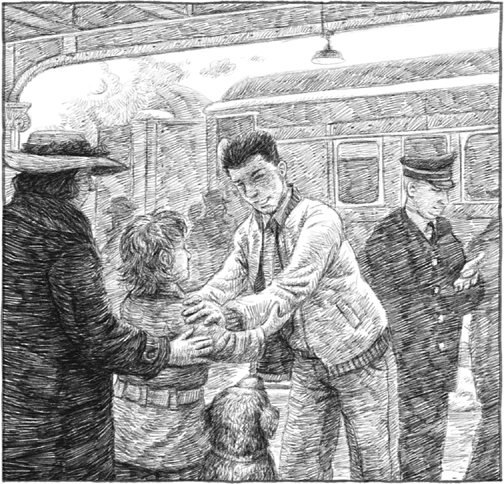

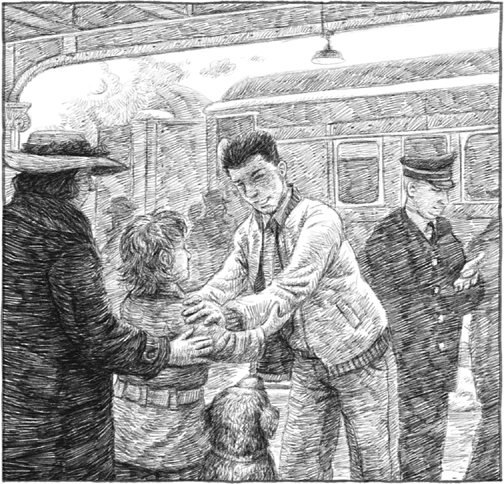

A week later the whole family and Jeep and Ebbs stood together in Washington’s huge Union Station. It was the biggest building Alex had ever been in, the waiting room an immense white marble hall with vaulted ceilings. Alex felt small in it. The government had sent Chuck a travel voucher to Fort Bliss with meals and everything provided. He seemed changed—serious, older, a little frightened. His chin-out, dare-’em edginess was gone. Alex had never seen him like that. It was like he’d settled into himself, wasn’t fighting to get out. It was like after trying on all sorts of different lives he’d finally found the one that fit.

His train was announced. They went to the platform.

There were hugs all around. John gave Chuck an envelope. “It’s the money I got tutoring Alex,” he explained. “Good luck.”

When Chuck got to Alex, he whispered, “Don’t worry, Alley. I’m going to do it right this time. I’m going to do it right for both of us. You’ll see.”

“Yes,” Alex said, clenching her teeth to keep from crying.

“Chin up, Alex,” Ebbs ordered as they rode home together. “We’ve got work to do. Starting now, we’re going to train you to be the astronaut VB said you’d be, get you ready for your Columbian moment.”

“My what?” Alex asked, blinking back tears.

“You’re gonna go off like Christopher Columbus,” Ebbs said. “Up and away—like his setting-out orders: ‘Nothing to the north, nothing to the south, nothing to the east’—only for you it’s nothing to the west either—just up! Right?”

“Right,” said Alex with a smile. She caught herself. “Right!”