Chapter 6

Communication and Network Security

IN THIS CHAPTER

Assessing and implementing secure design principles in network architectures

Assessing and implementing secure design principles in network architectures

Securing network components

Securing network components

Implementing secure communication channels according to design

Implementing secure communication channels according to design

The Communication and Network Security domain requires a thorough understanding of network fundamentals, secure network design, concepts of network operation, networking technologies, and network management techniques. This domain represents 14 percent of the CISSP certification exam.

Assess and Implement Secure Design Principles in Network Architectures

A solid understanding of networking concepts and fundamentals is essential for creating a secure network architecture. This understanding requires knowledge of network topologies; IP addressing; various networking protocols (including multilayer and converged protocols); wireless networks; communication security; and new and evolving networking trends, such as software-defined networks, microsegmentation, and cloud computing.

Data networks are commonly classified as local area networks and wide area networks. Although these classifications are basic, you should understand the fundamental distinctions between these two types of networks.

A local area network (LAN) is a data network that operates across a relatively small geographic area, such as a single building or floor. A LAN connects workstations, servers, printers, and other devices so that network resources, such as files and email, can be shared. Key characteristics of LANs include the following:

- Can connect networked resources over a small geographic area, such as a floor, a building, or a group of buildings.

- Are relatively inexpensive to set up and maintain, typically consisting of readily available equipment such as servers, desktop PCs, printers, switches, hubs, bridges, repeaters, wireless access points, and various security devices such as firewalls and intrusion prevention systems.

- Can be wired, wireless, or a combination of wired and wireless.

- Perform at relatively high speeds — typically 10 megabits per second (Mbps), 100 Mbps, 1000 Mbps (also referred to as 1 gigabit per second [1 Gbps]), 10 Gbps, and 40 Gbps for wired networks, and 11 Mbps, 54 Mbps, or 600 Mbps for wireless networks. We cover LAN speeds in the section “Physical Layer (Layer 1)” later in this chapter.

A wide area network (WAN) connects multiple LANs and other WANs by using telecommunications devices and facilities to form an internetwork. Key characteristics of WANs include the following:

- Connects multiple LANs over large geographic areas, such as a small city (such as a metropolitan area network), a region or country, a global corporate network, the entire planet (such as the Internet), or beyond (such as the International Space Station via satellite).

- Can be relatively expensive to set up and maintain, typically consisting of equipment such as routers, channel service unit/data service unit devices, firewalls, virtual private networks (VPNs), gateways, and various other security devices.

- Perform at relatively low speeds by using various technologies, such as digital subscriber line (DSL; 128 Kbps to 16 Mbps, for example), T-1 (1.544 Mbps), DS-3 (approximately 45 Mbps), OC-12 (approximately 622 Mbps), and OC-255 (approximately 13 Gbps). We cover WAN speeds in the section “Data Link Layer (Layer 2)” later in this chapter.

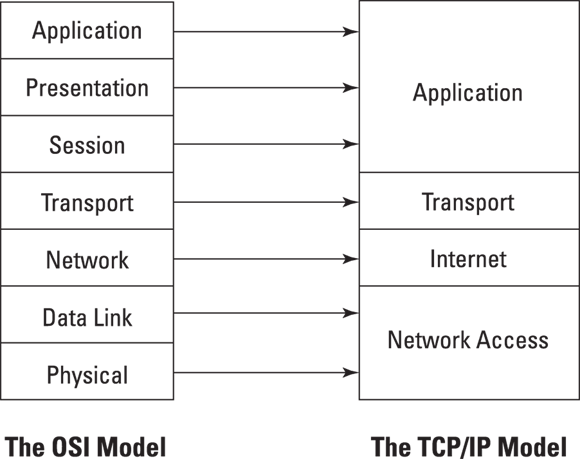

OSI and TCP/IP models

The OSI and TCP/IP models define standard protocols for network communication and interoperability by using a layered approach. This approach divides complex networking issues into simpler functional components that aid in the understanding, design, and development of networking solutions. It provides the following specific advantages:

- Clarifies the general functions of a communications process instead of focusing on specific issues

- Reduces complex networking processes into simpler sublayers and components

- Promotes interoperability by defining standard interfaces

- Aids development by allowing vendors to change individual features at a single layer instead of rebuilding the entire protocol stack

- Facilitates easier (and more logical) troubleshooting

The OSI Reference Model

In 1984, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) adopted the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Reference Model (or simply the OSI model) to facilitate interoperability between network devices independent of the manufacturer.

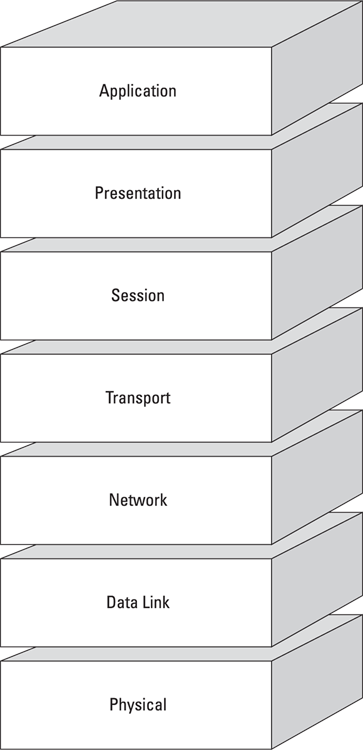

The OSI model consists of seven distinct layers that describe how data is communicated between systems and applications on a computer network, as shown in Figure 6-1. These layers include

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 6-1: The seven layers of the OSI model.

- Application (Layer 7)

- Presentation (Layer 6)

- Session (Layer 5)

- Transport (Layer 4)

- Network (Layer 3)

- Data Link (Layer 2)

- Physical (Layer 1)

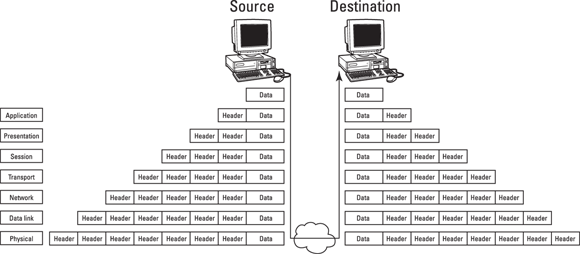

In the OSI model, data is passed from the highest layer (Application, Layer 7) downward through each layer to the lowest layer (Physical, Layer 1) and then transmitted across the network medium to the destination node, where it’s passed upward from the lowest layer to the highest layer. Each layer communicates only with the layer immediately above and below it (adjacent layers). This communication is achieved through a process known as data encapsulation, which wraps protocol information from the layer immediately above in the data section of the layer immediately below. Figure 6-2 illustrates this process.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 6-2: Data encapsulation in the OSI model.

Application Layer (Layer 7)

The Application Layer (Layer 7) is the highest layer of the OSI model. It supports the components that deal with the communication aspects of an application that requires network access, and it provides an interface to the user. So both the Application Layer and the end user interact directly with the application.

The Application Layer is responsible for the following:

- Identifying and establishing availability of communication partners

- Determining resource availability

- Synchronizing communication

Don’t confuse the Application Layer with software applications such as Microsoft Word and Excel. Applications that function at the Application Layer include

- File Transfer Protocol (FTP) and Secure File Transfer Protocol (SFTP): A program used to copy files from one system to another over a network. FTP operates on TCP ports 20 (the data port) and 21 (the control port), while SFTP only requires TCP port 22 by default.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP): The language of the World Wide Web, used by web servers and browsers for non-sensitive content. HTTP operates on TCP port 80.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS): The language of commercial transactions on the World Wide Web. HTTPS is actually the HTTP protocol used in combination with SSL/TLS (discussed in the section “Transport Layer (Layer 4)”). HTTPS operates on TCP port 443 but occasionally on other ports such as 8443.

- Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP): A store-and-forward electronic mail protocol that allows an email client to access, manage, and synchronize email on a remote mail server. IMAP provides more functionality and security than POP3, such as requiring users to explicitly delete emails from the server. The most current version is IMAPv4 (or IMAP4), which operates on TCP and UDP port 143. Email clients that use IMAP can be secured by using TLS or SSL encryption over TCP/UDP port 993.

- Post Office Protocol Version 3 (POP3): An email retrieval protocol that allows an email client to access email on a remote mail server by using TCP port 110. Inherently insecure, POP3 allows users to authenticate over the Internet by using plaintext passwords. Email clients that use POP3 can be secured by using TLS or SSL encryption over TCP/UDP port 995.

- Privacy Enhanced Mail (PEM): PEM is an Internet Engineering Task Force standard (IETF) for providing email confidentiality and authentication. PEM is not widely used.

- Secure Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (S/MIME): S/MIME is a secure method of sending email incorporated into several popular browsers and email applications.

- Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP): Used to send and receive email across the Internet. This protocol has several well-known vulnerabilities that make it inherently insecure. SMTP operates on TCP/UDP port 25. SMTP over SSL/TLS (SMTPS) uses TCP/UDP port 465.

- Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP): Used to collect network information by polling stations and sending traps (alerts) to a management station. SNMP has many well-known vulnerabilities, including default cleartext community strings (passwords). SNMP operates on TCP/UDP ports 161 (agent) and 162 (manager). Secure SNMP uses TCP/UDP ports 10161 (agent) and 10162 (manager).

- Telnet: Provides terminal emulation for remote access to system resources. Telnet operates on TCP/UDP port 23. Because Telnet transmits passwords in cleartext, it is no longer considered safe; SSH (discussed in the section “Session Layer (Layer 5)” later in this chapter) is preferred.

- Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP): A lean, mean version of FTP without directory-browsing capabilities or user authentication. Generally considered to be less secure than FTP, TFTP operates on UDP port 69.

Presentation Layer (Layer 6)

The Presentation Layer (Layer 6) provides coding and conversion functions that are applied to data being presented to the Application Layer (Layer 7). These functions ensure that data sent from the Application Layer of one system are compatible with the Application Layer of the receiving system.

Tasks associated with this layer include

- Data representation: Use of common data representation formats (standard image, sound, and video formats) enables application data to be exchanged between different types of computer systems.

- Character conversion: Information is exchanged between different systems by using common character conversion schemes.

- Data compression: Common data compression schemes enable compressed data to be decompressed properly at the destination.

- Data encryption: Common data encryption schemes enable encrypted data to be decrypted properly at the destination.

Examples of Presentation Layer protocols include

- American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII): A character-encoding scheme based on the English alphabet, consisting of 128 characters.

- Extended Binary-Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC): An 8-bit character-encoding scheme largely used on mainframe and mid-range computers.

- Graphics Interchange Format (GIF): A widely used bitmap image format that allows up to 256 colors and is suitable for images or logos (but not photographs).

- Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG): A photographic compression method widely used to store and transmit photographs.

- Motion Picture Experts Group (MPEG): An audio and video compression method widely used to store and transmit audio and video files.

Session Layer (Layer 5)

The Session Layer (Layer 5) establishes, coordinates, and terminates communication sessions (service requests and service responses) between networked systems.

A communication session is divided into three distinct phases:

- Connection establishment: Initial contact between communicating systems is made, and the end devices agree on communications parameters and protocols to be used, including the mode of operation:

- Simplex mode: In simplex mode, a one-way communications path is established with a transmitter at one end of the connection and a receiver at the other end. An analogy is AM radio; a radio station broadcasts music, and the radio receiver can only receive the broadcast.

- Half-duplex mode: In half-duplex mode, both communicating devices are capable of transmitting and receiving messages, but they can’t do so at the same time. An analogy is a two-way radio; a button must be pressed to transmit and then released to receive a signal.

- Full-duplex mode: In full-duplex mode, both communicating devices are capable of transmitting and receiving simultaneously. An analogy is a telephone; it can transmit and receive signals (but not necessarily communicate) at the same time.

- Data transfer: Information is exchanged between end devices.

- Connection release: When data transfer is complete, end devices systematically end the session.

Examples of Session Layer protocols include

- Network Basic Input/Output System (NetBIOS): A Microsoft protocol that allows applications to communicate over a LAN. When NetBIOS is combined with protocols such as TCP/IP, known as NetBIOS over TCP/IP (or NBT), applications can communicate over large networks.

- Network File System (NFS): Developed by Sun Microsystems to facilitate transparent user access to remote file-system resources on a Unix-based TCP/IP network.

- Remote Procedure Call (RPC): A client-server network redirection tool. Procedures are created on clients and performed on servers.

- Secure Remote Procedure Call (S-RPC): S-RPC is a secure client-server protocol that’s defined at multiple upper layers of the OSI model. RPC is used to request services from another computer on the network. S-RPC provides public and private keys to clients and servers by using Diffie-Hellman. After S-RPC operations initially authenticate, they’re transparent to the end user.

Secure Shell (SSH and SSH-2): SSH provides a secure alternative to Telnet (discussed in the section “Application Layer (Layer 7)” later in this chapter) for remote access. SSH establishes an encrypted tunnel between the client and the server, and can authenticate the client to the server. SSH can be used to protect the confidentiality and integrity of network communications. SSH-2 establishes an encrypted tunnel between the SSH client and SSH server, and can authenticate the client to the server. SSH version 1 is also widely used but has inherent vulnerabilities that are easily exploited.

SSH-2 (or SSH) is an Internet security application that provides secure remote access.

SSH-2 (or SSH) is an Internet security application that provides secure remote access.- Session Initiation Protocol (SIP): An open signaling protocol standard for establishing, managing and terminating real-time communications — such as voice, video, and text — over large IP-based networks.

Transport Layer (Layer 4)

The Transport Layer (Layer 4) provides transparent, reliable data transport and end-to-end transmission control. The Transport Layer hides the details of the lower layer functions from the upper layers.

Specific Transport Layer functions include

- Flow control: Manages data transmission between devices, ensuring that the transmitting device doesn’t send more data than the receiving device can process

- Multiplexing: Enables data from multiple applications to be transmitted over a single physical link

- Virtual circuit management: Establishes, maintains, and terminates virtual circuits

- Error checking and recovery: Implements various mechanisms for detecting transmission errors and taking action to resolve any errors that occur, such as requesting that data be retransmitted

Several important protocols defined at the Transport Layer include

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP): A full-duplex (capable of simultaneous transmission and reception), connection-oriented protocol that provides reliable delivery of packets across a network. A connection-oriented protocol requires a direct connection between two communicating devices before any data transfer occurs. In TCP, this connection is accomplished via a three-way handshake. The receiving device acknowledges packets, and packets are retransmitted if an error occurs. The following characteristics and features are associated with TCP:

- Connection-oriented: TCP establishes and manages a direct virtual connection to the remote device.

- Reliable: TCP guarantees delivery by acknowledging received packets and requesting retransmission of missing or corrupted packets.

- Slow: Because of the additional overhead associated with initial handshaking, acknowledging packets, and error correction, TCP is generally slower than connectionless protocols, such as User Datagram Protocol (UDP).

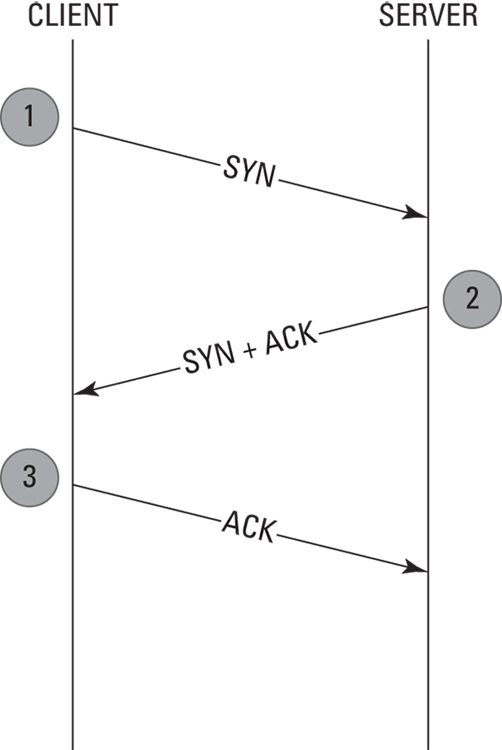

A three-way handshake is the method used to establish a TCP connection (see Figure 6-3). A PC attempting to establish a connection with a server initiates the connection by sending a TCP SYN (Synchronize) packet, which is the first part of the handshake. In the second part of the handshake, the server replies to the PC with a SYN ACK packet (Synchronize Acknowledgement). Finally, the PC completes the handshake by sending an ACK or SYN-ACK-ACK packet, acknowledging the server’s acknowledgement, and the data communications commence.

A three-way handshake is the method used to establish a TCP connection (see Figure 6-3). A PC attempting to establish a connection with a server initiates the connection by sending a TCP SYN (Synchronize) packet, which is the first part of the handshake. In the second part of the handshake, the server replies to the PC with a SYN ACK packet (Synchronize Acknowledgement). Finally, the PC completes the handshake by sending an ACK or SYN-ACK-ACK packet, acknowledging the server’s acknowledgement, and the data communications commence.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 6-3: The TCP three-way handshake.

A socket is a logical endpoint on a system or device used to communicate over a network to another system or device (or even on the same device). A socket usually is expressed as an IP address and port number, such as 192.168.100.2:25.

- User Datagram Protocol (UDP): A connectionless protocol that provides fast best-effort delivery of datagrams across a network. A connectionless protocol doesn’t guarantee delivery of transmitted packets (datagrams) and is thus considered unreliable. It doesn’t

- Attempt to establish a connection with the destination network prior to transmitting data

- Acknowledge received datagrams

- Perform re-sequencing

- Perform error checking or recovery

A datagram is a self-contained unit of data that is capable of being routed between a source and a destination. Similar to a packet, which is used in the Internet Protocol (IP), datagrams are commonly used in UDP and other protocols.

A datagram is a self-contained unit of data that is capable of being routed between a source and a destination. Similar to a packet, which is used in the Internet Protocol (IP), datagrams are commonly used in UDP and other protocols. The term Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is used to describe the unit of data used at a particular layer of a protocol. In OSI, the Layer 1 PDU is a bit, Layer 2’s PDU is a frame, Layer 3’s is a packet, and Layer 4’s is a segment or datagram, and Layer 7’s is message.

The term Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is used to describe the unit of data used at a particular layer of a protocol. In OSI, the Layer 1 PDU is a bit, Layer 2’s PDU is a frame, Layer 3’s is a packet, and Layer 4’s is a segment or datagram, and Layer 7’s is message.UDP is ideally suited for data that requires fast delivery as long as that data isn’t sensitive to packet loss and doesn’t need to be fragmented. Examples of applications that use UDP include Domain Name System, Simple Network Management Protocol, and streaming audio or video. The following characteristics and features are associated with UDP:

- Connectionless: Doesn’t pre-establish a communication circuit with the destination network

- Best effort: Doesn’t guarantee delivery and thus is considered to be unreliable

- Fast: Has no overhead associated with circuit establishment, acknowledgement, sequencing, or error-checking and recovery

Jitter in streaming audio and video is caused by variations in the delay of received packets, which is a negative characteristic of UDP.

Jitter in streaming audio and video is caused by variations in the delay of received packets, which is a negative characteristic of UDP.Sequenced Packet Exchange (SPX): The protocol used to guarantee data delivery in older Novell NetWare IPX/SPX networks. SPX sequences transmitted packets, reassembles received packets, confirms that all packets are received, and requests retransmission of packets that aren’t received. SPX is to IPX as TCP is to IP, though the order is stated as IPX/SPX rather than SPX/IPX (as in TCP/IP): SPX and TCP are Layer 4 protocols, and IPX and IP are Layer 3 protocols. Just think of the SPX-IPS and TCP-IP relationships as yang and yin, rather than yin and yang!

Several examples of connection-oriented and connectionless-oriented protocols are identified in Table 6-1.

- Secure Sockets Layer/Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS): The SSL/TLS protocol provides session-based encryption and authentication for secure communication between clients and servers on the Internet. SSL/TLS provides server authentication with optional client authentication.

- Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP): A message-oriented protocol (similar to UDP) that ensures reliable, in-sequence transport with congestion control (similar to TCP). SCTP also provides multihoming and redundant paths for resiliency and reliability.

TABLE 6-1 Connection-Oriented and Connectionless-Oriented Protocols

Protocol |

Layer |

Type |

|---|---|---|

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) |

4 (Transport) |

Connection-oriented |

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) |

4 (Transport) |

Connectionless-oriented |

IP (Internet Protocol) |

3 (Network) |

Connectionless-oriented |

ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol) |

3 (Network) |

Connectionless-oriented |

IPX (Internetwork Packet Exchange) |

3 (Network) |

Connectionless-oriented |

SPX (Sequenced Packet Exchange) |

4 (Transport) |

Connection-oriented |

Network Layer (Layer 3)

The Network Layer (Layer 3) provides routing and related functions that enable data to be transported between systems on the same network or on interconnected networks (or internetworks). Routing protocols — such as the Routing Information Protocol (RIP), Open Shortest Path First (OSPF), and Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) — are defined at this layer. Logical addressing of devices on the network is accomplished at this layer by using routed protocols, including IP and Internetwork Packet Exchange (IPX).

ROUTING PROTOCOLS

Routing protocols are defined at the Network Layer and specify how routers communicate with one another on a WAN. Routing protocols are classified as static or dynamic.

A static routing protocol requires an administrator to create and update routes manually on the router. If the route is down, the network is down. The router can’t reroute traffic dynamically to an alternative destination (unless a different route is specified manually). Also, if a given route is congested, but an alternative route is available and relatively fast, the router with static routes can’t route data dynamically over the faster route. Static routing is practical only on very small networks or for very limited, special-case routing scenarios (such as a destination that’s reachable only via a single router). Despite the limitations of static routing, it has a few advantages, such as low bandwidth requirements (routing information isn’t broadcast across the network) and some built-in security (users can get only to destinations that are specified in the routing table).

A dynamic routing protocol can discover routes and determine the best route to a given destination at any given time. The routing table is periodically updated with current routing information. Dynamic routing protocols are further classified as link-state and distance-vector (for intradomain routing) and path-vector (for interdomain routing) protocols.

A distance-vector protocol makes routing decisions based on two factors: the distance (hop count or other metric) and vector (the egress router interface). It periodically informs its peers and/or neighbors of topology changes. Convergence — the time it takes for all routers in a network to update their routing tables with the most current information, such as link status changes — can be a significant problem for distance-vector protocols. Without convergence, some routers in a network may be unaware of topology changes, causing the router to send traffic to an invalid destination. During convergence, routing information is exchanged between routers, and the network slows considerably.

Routing Information Protocol (RIP) is a distance-vector routing protocol that uses hop count as its routing metric. To prevent routing loops, in which packets effectively get stuck bouncing between various router nodes, RIP implements a hop limit of 15, which significantly limits the size of networks that RIP can support. After a data packet crosses 15 router nodes (hops) between a source and a destination, the destination is considered to be unreachable. In addition to hop limits, RIP employs three mechanisms to prevent routing loops:

- Split horizon: Prevents a router from advertising a route back out through the same interface from which the route was learned.

- Route poisoning: Sets the hop count on a bad route to 16, effectively advertising the route as unreachable if it takes more than 15 hops to reach.

- Holddown timers: Cause a router to start a timer when the router first receives information that a destination is unreachable. Subsequent updates about that destination will not be accepted until the timer expires. This mechanism also helps prevent problems associated with flapping, which occurs when a route (or interface) changes state (up, down, up, down) repeatedly over a short period.

RIP uses UDP port 520 as its transport protocol and port; thus, it is a connectionless-oriented protocol. Other disadvantages of RIP include slow convergence and insufficient security. (RIPv1 has no authentication, and RIPv2 transmits passwords in cleartext.) RIP is a legacy protocol, but it’s still in widespread use on networks today despite its limitations, because of its simplicity.

A link-state protocol requires every router to calculate and maintain a complete map, or routing table, of the entire network. Routers that use a link-state protocol periodically transmit updates that contain information about adjacent connections (called link states) to all other routers in the network. Link-state protocols are computation-intensive but can calculate the most efficient route to a destination, taking into account numerous factors such as link speed, delay, load, reliability, and cost (an arbitrarily assigned weight or metric). Convergence occurs very rapidly (within seconds) with link-state protocols; distance-vector protocols usually take longer (several minutes or even hours in very large networks). Two examples of link-state routing protocols are

- Open Shortest Path First (OSPF): OSPF is a link-state routing protocol widely used in large enterprise networks. It’s considered to be an interior gateway protocol because it performs routing within a single autonomous system. OSPF is encapsulated directly into IP datagrams, as opposed to using a Transport Layer protocol such as TCP or UDP. OSPF networks are divided into areas identified by 32-bit area identifiers. Area identifiers can (but don’t have to) correspond to network IP addresses and can duplicate IP addresses without conflicts. Special OSPF areas include the backbone area (also known as area 0), stub area, and not-so-stubby area.

- Intermediate System to Intermediate System (IS-IS): IS-IS is a link-state routing protocol used to route datagrams through a packet-switched network. This interior gateway protocol is used for routing within an autonomous system and is, used extensively in large service-provider backbone networks.

A path-vector protocol is similar in concept to a distance-vector protocol, but without the scalability issues associated with limited hop counts. Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is an example of a path-vector protocol. BGP is a path-vector routing protocol used between separate autonomous systems. It’s considered to be an exterior gateway protocol because it performs routing between separate autonomous systems. It’s the core protocol used by Internet service providers, network service providers, and very large private IP networks. When BGP runs between autonomous systems, it’s called external BGP (eBGP). When BGP runs within an autonomous system (such as on a private IP network), it’s called internal BGP (iBGP).

ROUTED PROTOCOLS

Routed protocols are Network Layer protocols, such as Internetwork Packet Exchange (IPX) and IP, which address packets with routing information and allow those packets to be transported across networks via routing protocols (discussed in the preceding section).

Internetwork Packet Exchange (IPX) is a connectionless protocol used primarily in older Novell NetWare networks for routing packets across the network. It’s part of the Internetwork Packet Exchange/Sequenced Packet Exchange (IPX/SPX) protocol suite, which is analogous to the TCP/IP suite.

IP contains addressing information that enables packets to be routed. IP is part of the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) suite, which is the language of the Internet. IP has two primary responsibilities:

- Connectionless, best-effort (no guarantee of) delivery of datagrams

- Fragmentation and reassembly of datagrams

IP Version 4 (IPv4), which is currently the most commonly used version, uses a 32-bit logical IP address that’s divided into four 8-bit sections (octets) and consists of two main parts: the network number and the host number. The first four bits in an octet are known as the high-order bits, and the last four bits in an octet are known as the low-order bits. The first bit in the octet is referred to as the most significant bit, and the last bit in the octet is referred to as the least significant bit. Each bit position represents its value (see Table 6-2) if the bit is on (1); otherwise, its value is zero (off or 0).

TABLE 6-2 Bit Position Values in an IPv4 Address

High-Order Bits |

Low-Order Bits |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Most significant bit |

Least significant bit |

||||||

128 |

64 |

32 |

16 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

Each octet contains an 8-bit number with a value of 0 to 255. Table 6-3 shows a partial list of octet values in binary notation.

TABLE 6-3 Binary Notation of Octet Values

Decimal |

Binary |

Decimal |

Binary |

Decimal |

Binary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

255 |

1111 1111 |

200 |

1100 1000 |

9 |

0000 1001 |

254 |

1111 1110 |

180 |

1011 0100 |

8 |

0000 1000 |

253 |

1111 1101 |

160 |

1010 0000 |

7 |

0000 0111 |

252 |

1111 1100 |

140 |

1000 1100 |

6 |

0000 0110 |

251 |

1111 1011 |

120 |

0111 1000 |

5 |

0000 0101 |

250 |

1111 1010 |

100 |

0110 0100 |

4 |

0000 0100 |

249 |

1111 1001 |

80 |

0101 0000 |

3 |

0000 0011 |

248 |

1111 1000 |

60 |

0011 1100 |

2 |

0000 0010 |

247 |

1111 0111 |

40 |

0010 1000 |

1 |

0000 0001 |

246 |

1111 0110 |

20 |

0001 0100 |

0 |

0000 0000 |

IPv4 addressing supports five address classes, indicated by the high-order (leftmost) bits in the IP address, as listed in Table 6-4.

TABLE 6-4 IP Address Classes

Class |

Purpose |

High-Order Bits |

Address Range |

Maximum Number of Hosts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

A |

Large networks |

0 |

1 to 126 |

16,777,214 (224-2) |

B |

Medium networks |

10 |

128 to 191 |

65,534 (216-2) |

C |

Small networks |

110 |

192 to 223 |

254 (28-2) |

D |

Multicast |

1110 |

224 to 239 |

N/A |

E |

Experimental |

1111 |

240 to 254 |

N/A |

Several IPv4 address ranges are also reserved for use in private networks, including

- 10.0.0.0–10.255.255.255 (Class A)

- 172.16.0.0–172.31.255.255 (Class B)

- 192.168.0.0–192.168.255.255 (Class C)

These addresses aren’t routable on the Internet and thus are often implemented behind firewalls and gateways by using Network Address Translation (NAT) to conserve IP addresses, mask the network architecture, and enhance security. NAT translates private, non-routable addresses on internal network devices to registered IP addresses when communication across the Internet is required. The widespread use of NAT and private network addresses somewhat delayed the inevitable depletion of IPv4 addresses, which is limited to approximately 4.3 billion due to its 32-bit format (232 = 4,294,967,296 possible addresses). But the thing about inevitability is that it’s … well, inevitable. Factors such as the proliferation of mobile devices worldwide, always-on Internet connections, inefficient use of assigned IPv4 addresses, and the spectacular miscalculation of IBM’s Thomas Watson — who in 1943 predicted that there would be a worldwide market for “maybe five computers” (he was no Nostradamus) — have led to the depletion of IPv4 addresses.

In 1998, the IETF formally defined IP Version 6 (IPv6) as the replacement for IPv4. IPv6 uses a 128-bit hexadecimal IP address (versus 32 bits for IPv4) and incorporates additional functionality to provide security, multimedia support, plug-and-play compatibility, and backward compatibility with IPv4. The main reason for developing IPv6 was to provide infinitely more network addresses than are available with IPv4 addresses. Okay, it’s not infinite, but it is ginormous — 2128 or approximately 3.4 × 1038 (that’s 340 hundred undecillion) unique addresses!

IPv6 addresses consist of 32 hexadecimal numbers grouped into eight blocks (sometimes referred to as hextels) of four hexadecimal digits, separated by a colon.

TABLE 6-5 Decimal, Hexadecimal, and Binary Notation

Decimal |

Hexadecimal |

Binary |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0000 |

1 |

1 |

0001 |

2 |

2 |

0010 |

3 |

3 |

0011 |

4 |

4 |

0100 |

5 |

5 |

0101 |

6 |

6 |

0110 |

7 |

7 |

0111 |

8 |

8 |

1000 |

9 |

9 |

1001 |

10 |

A |

1010 |

11 |

B |

1011 |

12 |

C |

1100 |

13 |

D |

1101 |

14 |

E |

1110 |

15 |

F |

1111 |

The basic format for an IPv6 address is

xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx

where x represents a hexadecimal digit (0–f).

Following is an example of an IPv6 address:

2001:0db8:0000:0000:0008:0800:200c:417a

There are several rules the IETF has defined to shorten an IPv6 address:

- Leading zeroes in an individual hextel can be omitted, but there must be at least one hexadecimal digit in each hextel (except as noted in the next rule). Applying this rule to the previous example yields the following result: 2001:db8:0:0:8:800:200c:417a.

- Two colons (::) can be used to represent one or more groups of 16 bits of zeros, as well as leading or trailing zeroes in an address, and can only appear once in an IPv6 address. Applying this rule to the previous example yields the following result: 2001:db8::8:800:200c:417a.

- In mixed IPv4 and IPv6 environments, the form x:x:x:x:x;x:d.d.d.d can be used, in which x represents the six high-order 16-bit hextels of the address and d represents the four low-order 8-bit octets (in standard IPv4 notation) of the address. 0db8:0:0:0:0:FFFF:129.144.52.38 is a valid IPv6 address. Applying the previous two rules to this example yields the following result: db8::ffff:129.144.52.38.

Security features in IPv6 include network-layer security via Internet Protocol Security and requirements defined in Request For Comments 7112 to prevent fragmentation exploits in IPv6 headers.

IMPLICATIONS OF MULTILAYER PROTOCOLS

Multilayer protocols are groups of protocols that are purpose-built for some type of specialized communications need. Multilayer protocols have their own schemes for encapsulation, like TCP/IP itself.

One good example of a multilayer protocol is Distributed Network Protocol (DNP3), which is used in industrial control systems (ICS) and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) networks. DNP3 has a Data Frame Layer, Transport Layer, and Application Layer.

DNP3’s original design lacks security features, such as authentication and encryption. Recent updates to the standard have introduced security protocols. Without security features, relatively simple attacks (such as eavesdropping, spoofing, and perhaps denial of service) can be carried out easily on specialized multiprotocol networks.

CONVERGED PROTOCOLS

Converged protocols refers to an implementation of two or more protocols for a specific communications purpose. Examples of converged protocols include

- Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS)

- Fibre Channel over Ethernet (FCoE)

- Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP)

- Session Initiation Protocol (SIP)

- Internet Small Computer System Interface (iSCSI)

SOFTWARE-DEFINED NETWORKS

Software-defined networks (SDN) represent the ability to create, configure, manage, secure, and monitor network elements rapidly and efficiently. SDN uses an open standards architecture that enables intelligent network functions, such as routing, switching, and load balancing (the overlay function), to be performed on virtual software that is installed on commodity network hardware (the physical underlay), similar to server virtualization. In SDN, network elements and network architectures are virtual, which enables organizations to build and modify their networks and network elements quickly.

As with other virtualization technologies, correct management of SDN requires policy, process, and discipline to avoid network sprawl (the phenomenon in which undisciplined administrators bypass change control processes and unilaterally create virtual network elements).

Related to SDN, software-defined WAN is discussed later in this chapter.

IPSEC

Internet Protocol Security (IPsec) is an IETF open standard for VPNs that operates at the Network Layer (Layer 3) of the OSI model. It’s the most popular and robust VPN protocol in use today. IPsec ensures confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity by using Layer 3 encryption and authentication to provide an end-to-end solution. IPsec operates in two modes:

- Transport: Only the data is encrypted.

- Tunnel: The entire packet is encrypted.

The two main protocols used in IPsec are

- Authentication Header (AH): Provides integrity, authentication, and nonrepudiation

- Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP): Provides confidentiality (encryption) and limited authentication

Each pair of hosts communicating in an IPsec session must establish a security association (SA), which is a one-way connection between two communicating parties; thus, two associations are required for each pair of communicating hosts. Additionally, each association supports only a single protocol (AH or ESP). Therefore, using both an AH and an ESP between two communicating hosts requires four security associations. A security association has three parameters that uniquely identify it in an IPsec session:

- Security Parameter Index (SPI): The SPI is a 32-bit string used by the receiving station to differentiate between SAs terminating on that station. The SPI is located within the AH or ESP header.

- Destination IP address: The destination address could be the end station or an intermediate gateway or firewall, but it must be a unicast address.

- Security Protocol ID: The Security Protocol ID must be an AH or ESP association.

Key management is provided in IPsec by using the Internet Key Exchange (IKE), which is a combination of three complementary protocols: the Internet Security Association and Key Management Protocol (ISAKMP), the Secure Key Exchange Mechanism, and the Oakley Key Exchange Protocol. Internet Key Exchange operates in three modes: Main, Aggressive, and Quick.

OTHER NETWORK LAYER PROTOCOLS

Other protocols defined at the Network Layer include Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) and Simple Key Management for Internet Protocols (SKIP).

ICMP is used for network control and diagnostics. Commonly used ICMP commands include ping and traceroute. Although ICMP is very helpful in troubleshooting routing and connectivity issues in a network, it is also commonly used by attackers for network reconnaissance, device discovery, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks (such as an ICMP flood).

SKIP is a Network Layer key management protocol used to share encryption keys. An advantage of SKIP is that it doesn't require a communication session to be established before it sends encrypted keys or packets. The protocol is bandwidth-intensive, however, because of the size of additional header information in encrypted packets.

NETWORKING EQUIPMENT AT THE NETWORK LAYER

The primary networking equipment defined at Layer 3 is routers and gateways.

Routers are intelligent devices that link dissimilar networks and use logical or physical addresses to forward data packets only to the destination network (or along the network path). Routers employ various routing algorithms (such as RIP, OSPF, and BGP) to determine the best path to a destination, based on variables that include bandwidth, cost, delay, and distance.

Gateways are created with software running on a computer (workstation or server) or router. Gateways link dissimilar programs and protocols by examining the entire Layer 7 data packet so as to translate incompatibilities. A gateway can be used, for example, to link an IP network to an IPX network or a Microsoft Exchange mail server to a Lotus Notes server (a mail gateway).

Data Link Layer (Layer 2)

The Data Link Layer ensures that messages are delivered to the proper device across a physical network. This layer also defines the networking protocol (such as Ethernet, USB, Wi-Fi, or token ring) used to send and receive data between individual devices. The Data Link Layer formats messages from layers above into frames for transmission, handles point-to-point synchronization and error control, and can perform link encryption.

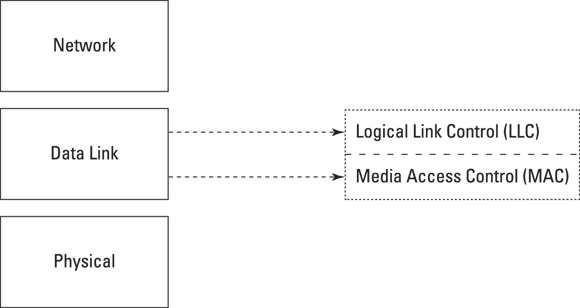

The IEEE 802 standards and protocols further divide the Data Link Layer into two sublayers: Logical Link Control (LLC) and Media Access Control (MAC), as shown in Figure 6-4.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 6-4: The LLC and MAC sublayers.

The LLC sublayer operates between the Network Layer above and the MAC sublayer below. The LLC sublayer performs the following three functions:

- Provides an interface for the MAC sublayer by using Source Service Access Points and Destination Service Access Points.

- Manages the control, sequencing, and acknowledgement of frames being passed up to the Network Layer or down to the Physical Layer.

- Bears responsibility for timing and flow control. Flow control monitors the flow of data between devices to ensure that a receiving device, which may not necessarily be operating at the same speed as the transmitting device, isn’t overwhelmed and dropping packets.

The MAC sublayer operates between the LLC sublayer above and the Physical Layer below. It’s responsible primarily for framing and has the following three functions:

- Performs error control: Error control uses a cyclic redundancy check (CRC), a simple mathematical calculation or checksum used to create a message profile. The CRC is recalculated by the receiving device. If the calculated CRC doesn’t match the received CRC, the packet is dropped, and a request to resend is transmitted back to the device that sent it.

- Identifies hardware device (or MAC) addresses: A MAC address (also known as a hardware address or physical address) is a 48-bit address that’s encoded on each device by its manufacturer. The first 24 bits identify the manufacturer or vendor. The second 24 bits uniquely identify the device.

- Controls media access: The three basic types of media access are

- Contention: In contention-based networks such as Ethernet, individual devices must vie for control of the physical network medium. This type of access is ideally suited to networks characterized by small bursts of traffic. Ethernet networks use a contention-based method, known as Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD), in which all stations listen for traffic on the physical network medium. If the line is clear, any station can transmit data. If another station attempts to transmit data at the same time, a collision occurs, the traffic is dropped, and both stations must wait a random period of time before attempting to retransmit. Another method, used in Wi-Fi networks, is known as Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA). Unlike CSMA/CD, CSMA/CA prevents collisions from occurring in the first place. This is accomplished by listening for traffic on the network. If the network is clear (or idle), a station waits a period of time (known as the inter-frame gap, or IFG) and then sends a frame. The sender station then sets a timer and waits for acknowledgement from the receiver that the frame was successfully received. If the acknowledgement is not received, the sender waits for a back-off time period and then re-transmits the frame.

- Token passing: In token-passing networks such as token ring and Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI), individual devices must wait for a special frame, known as a token, before they transmit data across the physical network medium. This type of network is considered to be deterministic (transmission delay can be reliably calculated, and collisions don’t occur) and is ideally suited for networks that have large, bandwidth-consuming applications that are delay-sensitive. Token ring, FDDI, and ARCnet networks use various token-passing methods for media access control.

- Polling: In polling networks, individual devices (secondary hosts) are polled by a primary host to see whether they have data to be transmitted. Secondary hosts can’t transmit until permission is granted by the primary host. Polling is typically used in mainframe environments and on wireless networks.

LAN PROTOCOLS AND TRANSMISSION METHODS

Common LAN protocols are defined at the Data Link and Physical layers, and include the following:

- Ethernet: The Ethernet protocol transports data to the physical LAN medium by using CSMA/CD (discussed in the preceding section). It is designed for networks characterized by sporadic, sometimes heavy traffic requirements. Ethernet is by far the most common LAN protocol used today, most often implemented with twisted-pair cabling (discussed in the section “Cable and connector types”). Ethernet operates at speeds up to 10 Mbps, Fast Ethernet operates at speeds up to 100 Mbps (over Cat 5 twisted-pair or fiber-optic cabling), and Gigabit Ethernet operates at speeds up to 40 Gbps (over Cat 5e, Cat 6, or Cat 7 twisted-pair or fiber-optic cabling).

- ARCNET: The Attached Resource Computer NETwork (ARCNET) protocol is one of the earliest LAN technologies developed. It transports data to the physical LAN medium by using the token-passing media access method that we discuss in the preceding section. It’s implemented in a star topology by using coaxial cable. ARCNET provides slow but predictable network performance.

- Token ring: The token ring protocol transports data to the physical LAN medium by using the token-passing media access method that we discuss in the preceding section. In a token ring network, all nodes are attached to a Multistation Access Unit (MAU) in a logical ring (but physical star) topology. One node on the token ring network is designated as the active monitor and ensures that no more than one token is on the network at any given time. (Variations permit more than one token on the network.) If the token is lost, the active monitor is responsible for ensuring that a replacement token is generated. Token ring networks operate at speeds of 4 and 16 Mbps — pretty slow by today’s standards. Token ring networks are rarely seen nowadays.

- Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI): The FDDI protocol transports data to the physical LAN medium by using the token-passing media access method that we discuss in the preceding section. It’s implemented as a dual counter-rotating ring over fiber-optic cabling at speeds up to 100 Mbps. All stations on a FDDI network are connected to both rings. During normal operation, only one ring is active. In the event of a network break or fault, the ring wraps back through the nearest node onto the second ring.

- Address Resolution Protocol (ARP): ARP maps Network Layer IP addresses to MAC addresses. ARP discovers physical addresses of attached devices by broadcasting ARP query messages on the network segment. Then IP-address-to-MAC-address translations are maintained in a dynamic table that’s cached on the system.

- Reverse Address Resolution Protocol (RARP): RARP maps MAC addresses to IP addresses. This process is necessary when a system, such as a diskless machine, needs to discover its IP address. The system broadcasts a RARP message that provides the system’s MAC address and requests to be informed of its IP address. A RARP server replies with the requested information.

LAN data transmissions are classified as

- Unicast: Packets are sent from the source to a single destination device by using a specific destination IP address.

- Multicast: Packets are copied and sent from the source to multiple destination devices by using a special multicast IP address that the destination stations have been specifically configured to use.

- Anycast: Packets are copied and sent from the source to a single destination IP address that is shared by several devices in multiple locations. Anycast is commonly used in CDNs (discussed earlier in this chapter).

- Broadcast: Packets are copied and sent from the source to every device on a destination network by using a broadcast IP address.

WIRELESS NETWORKS

Important wireless networks to be familiar with for the CISSP exam include Li-Fi, Wi-Fi, Near-Field Communication (NFC), ZigBee, and satellite.

Similar to fiber-optic networks, which use light rather than electrical signals to transmit data over wired networks, Li-Fi uses light in the visible, ultraviolet, and infrared spectrums rather than radio frequency to transmit data up to 100 Gbps over wireless networks.

WLAN (wireless LAN) technologies, commonly known as Wi-Fi, function at the lower layers of the OSI Reference Model. WLAN protocols define how frames are transmitted over the air. See Table 6-6 for a description of the most common IEEE 802.11 WLAN standards.

TABLE 6-6 Wireless LAN Standards

Type |

Speed |

Description |

|---|---|---|

802.11a |

54 Mbps |

Operates at 5 GHz (less interference than at 2.4 GHz) |

802.11b |

11 Mbps |

Operates at 2.4 GHz (first widely used protocol) |

802.11g |

54 Mbps |

Operates at 2.4 GHz (backward-compatible with 802.11b) |

802.11n |

600 Mbps |

Operates at 5 GHz or 2.4 GHz |

802.11ac |

1 Gbps |

Operates at 5 GHz |

802.11ad (WiGig) |

6.7 Gbps |

Operates at 60 GHz (range limited to 30 ft) |

802.11ah (WiFi HaLow) |

347 Mbps |

Operates at 900 MHz |

802.11ax (WiFi 6) |

10 Gbps |

Operates at 5 GHz or 2.4 GHz (backwards-compatible with 802.11a/b/g/n/ac) |

ZigBee is a low-cost, low-power wireless mesh network protocol based on the IEEE 802.15.4 standard. ZigBee is commonly used in industrial environments and smart home products. Various ZigBee specifications include ZigBee Pro, ZigBee Radio Frequency for Consumer Electronics (RF4CE), and ZigBee IP.

Near-Field Communication (NFC) is a set of communication protocols used over short distances (up to 4 cm), often used with smartphones for access control and contactless payments.

SATELLITE NETWORKS

Satellite broadband technologies are commonly used in remote areas where wired, wireless, or cellular services may not be readily available, as well as to provide backup connectivity. Other applications include providing connectivity for logistics (ships, planes, and trains) and communication backbones for IoT devices (such as fleet management and remote maintenance).

CELLULAR NETWORKS

Smartphones, IoT devices, and other mobile devices use cellular networks as well as Wi-Fi networks to communicate. The Third Generation Partnership Project defines the various generations and develops the protocols for mobile telecommunications (that is, cellular networks). The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) is a regulatory organization of the United Nations that is responsible for the global use of mobile telecommunication. Relevant cellular network generations include

- 3G: The first 3G networks provided minimum information transfer rates of 200 kilobits per second (Kbps). The ITU has never formally defined a standard for 3G data rates, so downlink data speeds vary widely from 384 Kbps for Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (W-CDMA) to 168 Mbps for Advanced Evolved High Speed Packet Access (HSPA+). 3G cellular networks are still commonly used in many countries and are increasingly being used as offload networks for 4G and 5G, as well as IoT applications.

- 4G: 4G Long-Term Evolution (LTE) mobile networks are currently the most commonly deployed cellular networks used for mobile technology. LTE networks are built on packet-switched all-IP core networks. LTE Advanced and LTE Advanced Pro have theoretical peak data rates of 1 Gbps and 3 Gbps, respectively.

- 5G: 5G networks deliver significantly higher speeds and lower latency than previous generations but also introduce many other important innovations to support a wide variety of use cases, including massive Machine-Type Communications (mMTC), Ultra Reliable and Low Latency Communication (URLLC), and enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB).

WAN TECHNOLOGIES AND PROTOCOLS

WAN technologies function at the lower three layers of the OSI Reference Model (the Physical, Data Link, and Network layers), primarily at the Data Link Layer. WAN protocols define how frames are carried across a single data link between two devices. These protocols include

- Point-to-point links: These links provide a single, pre-established WAN communications path from the customer’s network across a carrier network (such as a Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN)) to a remote network. These point-to-point links include

- Layer 2 Forwarding Protocol (L2F): A tunneling (data encapsulation) protocol developed by Cisco and used to implement VPNs, specifically Point-to-Point Protocol (discussed later in this section) traffic. L2F provides encapsulation but doesn’t provide encryption or confidentiality.

- Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (L2TP): A tunneling protocol used to implement VPNs. L2TP is derived from L2F (described in the preceding item) and PPTP (described in this list) and uses UDP port 1701 (see the section “Network Layer [Layer 3]” earlier in this chapter) to create a tunneling session. L2TP is commonly implemented along with an encryption protocol, such as IPsec, because it doesn’t encrypt traffic or provide confidentiality by itself. We discuss L2TP and IPsec in more detail in the section “Remote access” later in this chapter.

- Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP): The successor to SLIP (see the discussion later in this section), PPP provides router-to-router and host-to-network connections over synchronous and asynchronous circuits. It’s a more robust protocol than SLIP and provides additional built-in security mechanisms. PPP is far more common than SLIP in modern networking environments.

- Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP): A tunneling protocol developed by Microsoft and commonly used to implement VPNs, specifically PPP traffic. PPTP doesn’t provide encryption or confidentiality, instead relying on other protocols, such as PAP, CHAP, and EAP, for security. We discuss PPTP, PAP, CHAP, and EAP in more detail in the section “Remote access” later in this chapter.

- Serial Line IP (SLIP): The predecessor of PPP, SLIP was originally developed to support TCP/IP networking over low-speed asynchronous serial lines (such as dial-up modems) for Berkeley Unix computers. SLIP is rarely seen today except in computer museums.

- Circuit-switched networks: In a circuit-switched network, a dedicated physical circuit path is established, maintained, and terminated between the sender and receiver across a carrier network for each communications session (the call). This network type is used extensively in telephone company networks and functions similarly to a regular telephone call. Examples include

- Digital Subscriber Line (xDSL): xDSL uses existing analog phone lines to deliver high-bandwidth connectivity to remote customers.

Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN): ISDN is a communications protocol that operates over analog phone lines that have been converted to use digital signaling. ISDN lines are capable of transmitting both voice and data traffic. ISDN defines a B-channel for data, voice, and other services, and a D-channel for control and signaling information.

With the introduction and widespread adoption of DSL and DOCSIS, ISDN has largely fallen out of favor in the United States and is no longer available in many areas.

Circuit-switched networks are ideally suited for always-on connections that experience constant traffic.

Circuit-switched networks are ideally suited for always-on connections that experience constant traffic.Packet-switched networks: In a packet-switched network, devices share bandwidth (by using statistical multiplexing) on communications links to transport packets between a sender and receiver across a carrier network. This type of network is more resilient to error and congestion than circuit-switched networks. We compare packet-switched and circuit-switched networks in Table 6-7.

Examples of packet-switched networks include

- Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM): A very high-speed, low-delay technology that uses switching and multiplexing techniques to rapidly relay fixed-length (53-byte) cells that contain voice, video, or data. Cell processing occurs in hardware that reduces transit delays. ATM is ideally suited for fiber-optic networks that carry bursty (uneven) traffic.

- Data Over Cable Service Interface Specification (DOCSIS): A communications protocol for transmitting high-speed data over an existing cable TV system.

- Frame Relay: A packet-switched standard protocol that handles multiple virtual circuits by using High-level Data Link Control encapsulation (which we discuss later in this section) between connected devices. Frame Relay uses a simplified framing approach that has no error correction and Data Link Connection Identifiers to achieve high speeds across the WAN. Frame Relay can be used on Switched Virtual Circuits (SVCs) or Permanent Virtual Circuits (PVCs). An SVC is a temporary connection that’s dynamically created (in the circuit establishment phase) to transmit data (which happens during the data transfer phase) and then disconnected (in the circuit termination phase). PVCs are permanently established connections. Because the connection is permanent, a PVC doesn’t require the bandwidth overhead associated with circuit establishment and termination. PVCs are generally more expensive than SVCs.

- Multi-Protocol Label Switching (MPLS): A packet-switched, high-speed, highly scalable, highly versatile technology used to create fully meshed VPNs. It can carry IP packets as well as ATM, SONET (Synchronous Optical Networking), or Ethernet frames. MPLS is specified at both Layer 2 and Layer 3. Label Edge Routers (LERs) in an MPLS network push or encapsulate a packet (or frame) with an MPLS label. The label information is used to switch the payload through the MPLS cloud at very high speeds. Label Switch Routers within the MPLS cloud make routing decisions based solely on the label information without actually examining the payload. At the egress point, an LER pops (decapsulates) the packet, removing the MPLS label when the packet exits the MPLS network. One advantage of an MPLS network is that a customer loses visibility into the cloud. If you’re a glass-half-full type, one advantage of an MPLS network is that an attacker loses visibility into the cloud.

- Synchronous Optical Network (SONET) and Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH): A high-availability, high-speed, multiplexed, low-latency technology used on fiber-optic networks. SONET was originally designed for the public telephone network and is widely used throughout the United States and Canada, particularly within the energy industry. SDH was developed after SONET and is used throughout the rest of the world. Data rates for SONET and SDH are defined at optical carrier (OC) levels (see Table 6-8).

- Switched Multimegabit Data Service (SMDS): A high-speed, packet-switched, connectionless-oriented, datagram-based technology available over public switched networks. Typically, companies that exchange large amounts of data bursts with other remote networks use SMDS.

- X.25: The first packet-switching network, X.25 is an International Telecommunication Union – Telecommunications (ITU-T) standard that defines how point-to-point connections between data terminal equipment (DTE) and data carrier equipment (DCE) are established and maintained. X.25 specifies the Link Access Procedure, Balanced (LAPB) protocol at the Data Link Layer and the Packet Level Protocol (PLP; also known as X.25 Level 3) at the Network Layer. X.25 is more common outside the United States but largely has been superseded by MPLS and Frame Relay.

Packet-switched networks are ideally suited for on-demand connections that have bursty traffic.

Packet-switched networks are ideally suited for on-demand connections that have bursty traffic.- Other WAN protocols: Two other important WAN protocols defined at the Data Link Layer include

- High-level Data Link Control (HDLC): A bit-oriented, synchronous protocol that was created by the ISO to support point-to-point and multipoint configurations. Derived from SDLC, it specifies a data encapsulation method for synchronous serial links and is the default for serial links on Cisco routers. Unfortunately, various vendor implementations of the HDLC protocol are incompatible.

- Synchronous Data Link Control (SDLC): A bit-oriented, full-duplex serial protocol that was developed by IBM to facilitate communications between mainframes and remote offices. It defines and implements a polling method of media access, in which the primary (front end) polls the secondaries (remote stations) to determine whether communication is required.

WAN protocols and technologies are implemented over telecommunications circuits. Refer to Table 6-8 for a description of common telecommunications circuits and speeds.

TABLE 6-7 Circuit Switching versus Packet Switching

Circuit Switching |

Packet Switching |

|---|---|

Ideal for always-on connections, constant traffic, and voice communications |

Ideal for bursty traffic and data communications |

Connection-oriented |

Connectionless-oriented |

Fixed delays |

Variable delays |

TABLE 6-8 Common Telecommunications Circuits

Type |

Speed |

Description |

|---|---|---|

DS0 |

64 Kbps |

Digital Signal Level 0, framing specification used in transmitting digital signals over a single channel at 64 Kbps on a T1 facility |

DS1 |

1.544 Mbps or 2.048 Mbps |

Digital Signal Level 1, framing specification used in transmitting digital signals at 1.544 Mbps on a T1 facility (U.S.) or at 2.048 Mbps on an E1 facility (EU) |

DS3 |

44.736 Mbps |

Digital Signal Level 3, framing specification used in transmitting digital signals at 44.736 Mbps on a T3 facility |

T1 |

1.544 Mbps |

Digital WAN carrier facility; transmits DS1-formatted data at 1.544 Mbps (24 DS0 user channels at 64 Kbps each) |

T3 |

44.736 Mbps |

Digital WAN carrier facility; transmits DS3-formatted data at 44.736 Mbps (672 DS0 user channels at 64 Kbps each) |

E1 |

2.048 Mbps |

Wide-area digital transmission scheme used primarily in Europe that carries data at a rate of 2.048 Mbps |

E3 |

34.368 Mbps |

Wide-area digital transmission scheme used primarily in Europe that carries data at a rate of 34.368 Mbps (16 E1 signals) |

OC-1 |

51.84 Mbps |

SONET (Synchronous Optical Networking) Optical Carrier WAN specification |

OC-3 |

155.52 Mbps |

SONET |

OC-12 |

622.08 Mbps |

SONET |

OC-48 |

2.488 Gbps |

SONET |

OC-192 |

9.9 Gbps |

SONET |

OC-768 |

39 Gbps |

SONET |

NETWORKING EQUIPMENT AT THE DATA LINK LAYER

Networking devices that operate at the Data Link Layer include bridges, switches, DTEs/DCEs, and wireless equipment:

- A bridge is a semi-intelligent repeater used to connect two or more (similar or dissimilar) network segments. A bridge maintains an Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) cache that contains the MAC addresses of individual devices on connected network segments. When a bridge receives a data signal, it checks its ARP cache to determine whether the destination MAC address is on the local network segment. If the data signal turns out to be local, it isn’t forwarded to a different network. If the MAC address isn’t local, however, the bridge forwards (and amplifies) the data signal to all other connected network segments. A serious networking problem associated with bridges is a broadcast storm, in which broadcast traffic is automatically forwarded by a bridge, effectively flooding a network. Network bridges have been superseded by switches (discussed next).

- Data Terminal Equipment (DTE) is a general term used to classify devices at the user end of a user-to-network interface (such as computer workstations). A DTE connects to Data Carrier Equipment (DCE; also known as Data Circuit-Terminating Equipment), which consists of devices at the network end of a user-to-network interface. The DCE provides the physical connection to the network, forwards network traffic, and provides a clocking signal to synchronize transmissions between the DCE and the DTE. Examples of DCEs include NICs (Network Interface Cards), modems, and CSUs/DSUs (Channel Service Units/Data Service Units).

Wireless Access Points (APs) are transceivers that connect wireless clients to the wired network. Access points are base stations for the wireless network. They’re essentially hubs (or routers) operating in half-duplex mode — they can only receive or transmit at a given time; they can’t do both at the same time (unless they have multiple antennas). Wireless access points use antennas to transmit and receive data. The four basic types of wireless antennas are

- Omnidirectional: The most common type of wireless antenna, omnidirectional antennas are essentially short poles that transmit and receive wireless signals with equal strength in all directions around a horizontal axis. Omnidirectional antennas often employ a dipole design.

- Parabolic: Also known as dish antennas, parabolic antennas are directional dish antennas made of meshed wire grid or solid metal. Parabolic antennas are used to extend wireless ranges over great distances.

- Sectorized: Similar in shape to omnidirectional antennas, sectorized antennas have reflectors that direct transmitted signals in a specific direction (usually, a 60- to 120-degree pattern) to provide additional range and decrease interference in a specific direction.

- Yagi: Similar in appearance to a small aerial TV antenna, yagi antennas are used for long distances in point-to-point or point-to-multipoint wireless applications.

Client devices in a Wi-Fi network include desktop and laptop PCs, as well as mobile devices and other endpoints (such as smartphones, medical devices, bar-code scanners, and many so-called smart devices such as thermostats and other home automation devices). Wireless network interface cards (or wireless cards) come in a variety of forms, such as PCI adapters, PC cards, and USB adapters or are built into wireless-enabled devices, such as laptop PCs, tablets, and smartphones.

Access points and the wireless cards that connect to them must use the same WLAN 802.11 standard or be backward-compatible. See the section “Wireless networks” earlier in this chapter for a list of the 802.11 specifications.

Access points (APs) can operate in one of four modes:

- Root (also infrastructure): The default configuration for most APs. The AP is directly connected to the wired network, and wireless clients access the wired network via the wireless access point.

- Repeater (also stand-alone): The AP doesn’t connect directly to the wired network but provides an upstream link to another AP, effectively extending the range of the WLAN.

- Bridge: A rare configuration that isn’t supported in most APs. Bridge mode is used to connect two separate wired network segments via a wireless access point.

- Mesh: Multiple APs work together to create the appearance of a single Wi-Fi network for larger homes and workspaces.

Physical Layer (Layer 1)

The Physical Layer sends and receives bits across the network medium (cabling or wireless links) from one device to another.

It specifies the electrical, mechanical, and functional requirements of the network, including network topology, cabling and connectors, and interface types, as well as the process for converting bits to electrical (or light) signals that can be transmitted across the physical medium. Various network topologies, made from copper or fiber-optic wires and cables, hubs, and other physical materials, comprise the Physical Layer.

NETWORK TOPOLOGIES

Four basic network topologies are defined at the Physical Layer. Although there are many variations of the basic types — such as FDDI, star-bus (or tree), and star-ring — we stick to the basics here:

- Star: Each individual node on the network is connected directly to a switch, hub, or concentrator. All data communications must pass through the switch (or hub), which can become a bottleneck or single point of failure. A star topology is ideal for practically any size environment and is the most common basic topology in use today. A star topology is also easy to install and maintain, and network faults are easily isolated without affecting the rest of the network.

- Mesh: All systems are interconnected to provide multiple paths to all other resources. In most networks, a partial mesh is implemented for only the most critical network components, such as routers, switches, and servers (by using multiple network interface cards or server clustering) to eliminate single points of failure.

- Ring: A closed loop connects end devices in a continuous ring. Functionally, this topology is achieved by connecting individual devices to a Multistation Access Unit (MSAU or MAU). Physically, this setup gives the ring topology the appearance of a star topology. Ring topologies are common in token ring and FDDI networks. In a ring topology, all communication travels in a single direction around the ring.

- Bus: In a bus (or linear bus) topology, all devices are connected to a single cable (the backbone) that’s terminated on both ends. Bus networks were commonly used for very small networks because they were inexpensive and easy to install. In large environments, they were impractical because the media had physical limitations (namely, the length of the cabling), the backbone was a single point of failure (a break anywhere on the network affects the entire network), and tracing a fault in a large network could be extremely difficult. Bus networks are extremely rare today and are no longer the least expensive or easiest to install network option.

CABLE AND CONNECTOR TYPES

Cables carry the electrical or light signals that represent data between devices on a network. Data signaling is described by several characteristics, including type (see the sidebar “Analog and digital signaling” in this chapter), control mechanism (see the sidebar “Asynchronous and synchronous communications,” in this chapter), and classification (baseband or broadband). Baseband signaling uses a single channel for transmission of digital signals and is common in LANs that use twisted-pair cabling. Broadband signaling uses many channels over a range of frequencies for transmission of analog signals, including voice, video, and data. The four basic cable types used in networks include

- Coaxial cable: Coaxial (abbreviated as coax and pronounced KOH-axe) cable consists of a single, solid-copper-wire core, surrounded by a plastic or Teflon insulator, braided-metal shielding, and (sometimes) a metal foil wrap, all covered with a plastic sheath. This construction makes the cable very durable and resistant to Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) and Radio Frequency Interference (RFI) signals. Coax cable is commonly used to connect cable or satellite television receivers (the cable that goes from the black box to the wall). Note that coax cable used for television signals is not compatible with coax cable used for computer networking due to different capacitance. Coax cable comes in two flavors, thick and thin:

- Thick: Also known as RG8 or RG11 or thicknet, thick cable uses a screw-type connector, known as an Attachment Unit Interface (AUI).

- Thin: Also known as RG58 or thinnet, thin cable is typically connected to network devices by a Bayonet Neill-Concelman (BNC) connector.

Twinaxial cable: Twinaxial (also known as twinax) cable is very similar to coax cable, but it consists of two solid copper-wire cores rather than a single core. Twinax is used to achieve high data transmission speeds (such as 10 Gb Ethernet over very short distances such as 10 meters) at a relatively low cost. Typical applications for twinax cabling include SANs and top-of-rack network switches that connect critical servers to a high-speed core. Other advantages of twinax cabling include lower transceiver latency (delay in transmitter/receiver devices), low power consumption (compared with 10 GbE twisted-pair cables), and low bit error ratios.

Bit error ratio (BER) is the ratio of incorrectly received bits to total received bits over a specified period of time.

Bit error ratio (BER) is the ratio of incorrectly received bits to total received bits over a specified period of time.Twisted-pair cable: Twisted-pair cable is the most popular LAN cable in use today. It’s lightweight, flexible, inexpensive, and easy to install. One easily recognized example of twisted-pair cable is common telephone wire.

Twisted-pair cable consists of four copper-wire pairs that are twisted together to improve the transmission quality of the cable by reducing crosstalk and attenuation. The tighter the twisted pairs, the better the transmission speed and quality.

Crosstalk occurs when a signal transmitted over one channel or circuit negatively affects the signal transmitted over another channel or circuit. An (ancient) example of crosstalk occurred over analog phone lines when you could hear parts of other conversations over the phone. Attenuation is the gradual loss of intensity of a wave (such as electrical or light) while it travels over or through a medium.

Crosstalk occurs when a signal transmitted over one channel or circuit negatively affects the signal transmitted over another channel or circuit. An (ancient) example of crosstalk occurred over analog phone lines when you could hear parts of other conversations over the phone. Attenuation is the gradual loss of intensity of a wave (such as electrical or light) while it travels over or through a medium.Currently, 10 categories of twisted-pair cabling exist, but only Cat 5/5e, Cat 6/6a, and Cat 7/7a cable are typically used for networking today (see Table 6-9).

Twisted-pair cable can be unshielded (UTP) or shielded (STP). UTP cabling is more common because it’s easier to work with and less expensive than STP. STP is used when noise is a problem or when security is a major concern and is popular in IBM rings. Noise is produced by external sources and can distort or otherwise impair the quality of a signal. Examples of noise include RFI and EMI from sources such as electrical motors, radio signals, fluorescent lights, microwave ovens, and electronic equipment. Shielded cabling also reduces electromagnetic emissions that may be intercepted by an attacker.

TEMPEST is a (previously classified) U.S. military term that refers to the study of electromagnetic emissions from computers and related equipment.

TEMPEST is a (previously classified) U.S. military term that refers to the study of electromagnetic emissions from computers and related equipment.Twisted-pair cable is terminated with an RJ-type terminator. The three common types of RJ-type connectors are RJ-11, RJ-45, and RJ-49. Although these connectors are similar in appearance (particularly RJ-45 and RJ-49), only RJ-45 connectors are used for LANs. RJ-11 connectors are used for analog phone lines, and RJ-49 connectors are commonly used for ISDN lines and WAN interfaces.