BOTALLACK

Towards Cape Cornwall

The landscape of St Just is Cornwall apart, a bleak, dramatic graveyard of a place, as if County Durham had come south to die. Small groups of plain houses, chapels and workaday shops sit in an infertile terrain. Behind the village of Botallack a lane leads down to the sea, where the coast is a wilderness of bare rocks and beating waves. Vegetation thins and battered ruins appear, often through a thick sea mist. The ground heaves and dips towards the shore. Granite gives way to rusty shale. This is the land of tin.

The rocks of Botallack are a geologist’s paradise. Layers of copper, quartz, garnet, cobalt, uranium and arsenic were here ‘exhaled’ through volcanic fissures. Lodes of molten earth ran vertically and diagonally, requiring an impenetrable nomenclature of metapelite hornfels and pegmatite dykes. The ground at our feet shimmers with metallic colour.

Celts and Romans mined these parts. In 1539 the historian John Norden wrote that Botallack was ‘a little hamlet on the coaste of the Irishe sea most visited with tinners, where they lodge and feede’. The need of the industrial revolution for tin and copper led to a boom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with Botallack at its peak in the 1860s. The famous Boscawen diagonal shaft drove 400 feet down and half a mile out to sea from the Crowns mine.

The engine house and chimney of Crowns are reached by a vertiginous path down the cliff. Miners told of their terror at the sound of rocks rumbling in the surf above their heads. The experience attracted tourists, including Queen Victoria in 1846. The writer Wilkie Collins admitted to being petrified. Such was the popularity of the place that visitors were charged the then huge entry of half a guinea, to be used for the much-needed relief of deceased or incapacitated miners’ families.

The St Just coast to Cape Cornwall: shrines to the gods of rock

The arrival of cheap tin from Australia in the 1870s made Cornish tin less profitable. By the turn of the century Botallack had all but ceased production, its engines having to work ever harder to pump water from the shafts. The gaunt buildings began to disappear and today just thirteen engine houses survive. The Botallack group includes the old counting house, the ruin of an arsenic works with sheds and trackways. The Levant mine over the hill to the north lived on into the 1960s and Geevor until 1990. The latter is now a museum.

The best view of Botallack is from the cliff top a quarter of a mile north along the coast path, with a scramble down onto a cliffside slab. From here we can see the two cliffside engine houses of Crowns immediately below, with behind them the coast to Cape Cornwall and its offshore islands. The view is dotted with engine houses and chimneys, disused shrines to the gods of the rocks, reminding me of parts of Norfolk where ruined churches stretch to the horizon.

Here even the ubiquitous cliff heather seems meagre and halfhearted, as if admitting its defeat by geology. The rocks offshore are equally unforgiving. The marine floor along this coast is thick with wrecks, rich pickings for future archaeologists. Only the sky is alive, with cormorants circling like vultures, feeding on the history of the place.

CARRICK ROADS

From Trelissick

At Carrick Roads every prospect pleases. The Scots would call this a sea loch, an enclosed expanse of calm water across which boats scurry in safety and the sea seems far away. At its entrance we can stand astride the battlements of Pendennis and look down on Falmouth. On its eastern shore we can walk the shoreline of St Mawes to the sub-tropical gardens of Roseland. We can snooze in the sun in Mylor churchyard.

Carrick Roads vies with Rio de Janeiro and Halifax, Nova Scotia, for the title of largest natural harbour in the world. It is a classic ria, or deep glacial valley, flooded after the ice age by the incoming sea. The outer bays have long offered refuge from Atlantic storms to sailing ships rounding the Lizard, guided by the lighthouse on St Anthony Head. Though steam mostly brought an end to this role, the Roads were used to shelter convoys in two world wars. Falmouth harbour has become the terminus for round-the-world sailors such as Sir Robin Knox-Johnston and Dame Ellen MacArthur.

The inland reaches become more intimate and exciting. The Roads dissolve into Restronguet Creek and the fjord-like inlet of the King Harry Ferry. These creeks are steep-sided and deep, ideal for mothballing container ships and tankers. An adjacent coastal lane offers surreal glimpses of maritime superstructures seemingly suspended in the trees. I have seen tankers moored here in a line astern, like victims of some bizarre GPS malfunction.

The best view of Carrick Roads is south from the Trelissick peninsula, where a meadow sweeps down to the water’s edge, its convex curve creating a distant illusion of cows grazing amid bobbing masts and sails. Sky and glistening water are framed by tall trees. This is a place of peace.

Grass meets water meets sky: Trelissick towards Falmouth

From here the lie of the land has the Roads drifting out towards the sea, its shore bending gently from one side to the other like the shoulders of the ria it once was. To the right is the Feock peninsula, to the left Camerance Point. Next on the right is the creek of Mylor village, with the misty outline of the Fal estuary beyond. Each promontory slides easily into the water, crowned by trees. The only sign of life is the occasional yacht, attended by egrets, herons and grebes. Nothing is in a hurry.

On either side of the meadow lie the gardens of Trelissick House, oaks, beeches and pines interspersed with dense rhododendron, camellia and azalea. The garden is home to the national collection of photinia. More exotic species such as banana, palm and tree fern flourish inland.

CLOVELLY

Clovelly is famously attractive. A single cobbled street, known as Up-along, Down-along, stumbles down an isolated coastal ravine to a bay and small harbour. Public access is on foot (or donkey) and requires good legs and flat shoes. Residents have to haul their goods on sledges. They must have strong lungs.

Credit for preserving Clovelly goes to Christine Hamlyn, a former owner who restored the cottages in the 1930s and installed plumbing and lighting. Her initials adorn many of the buildings. The main street is attended by tiny courtyards through vaulted passages. There is no room for a square or church, other than a tiny chapel. Village business takes place where it always did, round the harbour below.

Clovelly before restoration, painting by Anna Brewster, 1895

Confronted by the popularity that Hamlyn’s preservation brought in its train, her descendants (now the Rouses) decided in the 1980s to turn its car park and access point into a large supermarket. Visitors now enter, pay to visit and leave Clovelly through a shopping mall. It has become a gift shop with a village attached. This is dismaying, yet nothing can detract from the intrinsic charm of the place. It has the quality of a Greek island settlement while remaining unmistakably English.

Halfway downhill, the street reaches a small plateau from where there is a view both up and down. Upwards, the curve of the street is defined by cottage walls, lime-washed white, cream, lemon and pink. Devon slates cover the roofs and windows are wooden casements. From every crevice erupt petunia, geranium, hydrangea and fuchsia. As the eye travels upwards, the street line is broken by an intimation of courtyards and alleys, everywhere backed by the trees of the surrounding cliff.

The view downhill to the harbour is quite different. The village’s existence depended on fishing and sea rescue, its harbour built in Tudor times. As the only haven along this stretch of coast its accessibility to the herring grounds of Lundy brought it prosperity. By the late nineteenth century the Red Lion hotel was already attracting seaborne tourists from Bristol and Wales. On my last visit, the harbour was hosting a crowded shellfish festival.

The harbour is set against the backdrop of the obscurely named Bight a Doubleyou, curving round to Bideford Bay. It is a Mediterranean prospect, contrasting starkly with Hartland Point to the south-west with its crashing Atlantic rollers.

There is an undeniable tweeness to Clovelly. Houses are called Crazy Kate’s Cottage and Rat’s Castle. Residents warn, Beware: Grumpy Old Women, or Remove Your Choos. But for all the complaints about ‘Disneyfication’ such places are alive. Their industry may be tourism rather than fish and smuggling, but a quarter of a million visitors a year are real. The goods they buy may seem down-market, but that does not invalidate the enterprise. Above all, Clovelly continues to please the eye.

DARTMOOR

From Haytor

Haytor is Dartmoor accessible: popular, touristy, anything but Dartmoor profond. I was warned to shun its coach parties and head west, to the bogs and mires of the interior, to Conan Doyle’s Baskerville country and Princetown’s notorious jail. But while they may be more remote, Haytor has the most commanding view, a 360-degree sweep of moorland and sea, hill and valley. Its tor is the finest on the moor.

Granite Haytor, Dartmoor in the distance

Dartmoor is England’s biggest dome of volcanic granite, heaving up through the Devonian sandstone to form the highest land in the south-west. On the peaks, erosion has worked on the fissures in the granite to create tors of rounded rock. These now stand as such distinctive features that it was once thought they were carved by hand, familiarly described as cyclopean. There are some 120 of these tors, among the strangest geological formations in England, surrounded by some 250 square miles of mostly peat moorland. Local churches made of this granite are rough-cast and crude, blunting the keenest chisel.

Haytor was long a granite quarry. The old workings can be seen to the north east, a landscape of smashed megaliths and deep pools. Rail tracks are still visible in places. The stone was much prized for its durability, used for many London bridges, and best seen in the hard grey base of Nelson’s Column.

The tor’s car park may be crowded, but the walk to the summit sorts out the strong from the weak. The final scramble onto the crowning boulder is by no means easy, up smooth slabs of unyielding granite. I must admit to getting so stuck I needed help to get down. The view from the top embraces a sizeable expanse of south-west England, a panorama from Dartmoor and Exmoor in the north to the inlets of the Devon coast and the English Channel in the south.

Dominant is Dartmoor itself, a rolling wilderness that seems to extend for ever. Each prominence is topped by its own distinctive boulder, as if the landscape had been furnished by Henry Moore. The ground is largely blanket bog, among the wettest in England. The vegetation is mainly cotton-grass, sedge, sphagnum and moss, often lying thin over pools of water unable to penetrate the granite. This creates the notorious mires into which people and horses can sink.

The landscape is bare of trees other than a scattering of birch and pine. Sheep and ponies eke out a living, helped by the occasional dark combe where a watercourse has slashed its way into the granite cap. Loveliest of these is due west of Haytor, at Widecombein-the-Moor, where the barren hillside swoops down in a fertile valley, marked by a superb Perpendicular steeple.

The view east is wholly different from the moor, showing the lush woodlands of the Exe valley with Exmoor’s Dunkery Beacon in the far distance. To the south lies the sea, flanked by the expanse of Lyme Bay, Chesil Beach and Portland Bill, the celebrated Jurassic coast. In the foreground, the Haldon Hills shield Exmouth and Dawlish from view, but we can make out Newton Abbot and the suburbs of Torquay.

Haytor is in the manner of a border fortress. For centuries after the Roman withdrawal, it defied the invading Saxons and guarded a distinctive Celtic language and culture to its west. This culture vanished from all other parts of England, from Cumbria and the Scottish border country, surviving only across Offa’s Dyke and Hadrian’s Wall. Cornish – Kernewek – lasted into the eighteenth century and is now being revived. To this day some Cornish flirt with independence, and refer to the English as outsiders.

DARTMOUTH

From Dyer’s Hill

This is ocean-going England, a coastline that looked not to Europe but to the Atlantic and the world beyond. Of its many deep-water shelters, Plymouth was the grandest and Falmouth the biggest, but the lesser havens of Salcombe, Helford and Dartmouth served the same purpose. Each has its champions, but to me Dartmouth is the most appealing.

JMW Turner’s evocation of Dartmouth Cove from Dyer’s Hill, c. 1822

Two cliffs guard its steep, wooded entrance, with medieval castles on either side. These were once linked by chains laid under the narrow estuary entrance, to be raised in emergency to obstruct attackers. It was here that the mischievous ‘historian’ Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed Brutus, grandson of Aeneas, landed from France to become first king of the Britons. If you believe this you can go to Totnes and see the stone on which he declared himself monarch.

It was at Dartmouth that crusader fleets mustered in the twelfth century to sail for the Mediterranean. Here was the base of the medieval wine trade with Bordeaux. Dartmouth was also the departure point for the Pilgrim Fathers to America, before they were driven into Plymouth Sound by a storm. There are as many Dartmouths in America as there are Plymouths.

The viewpoint overlooks the first elbow of the Dart river creek, from Dyer’s Hill above Warfleet. From here we can see down what is almost a ravine to one of the entry castles. On the slope opposite thick trees give way to smooth meadows on the hill crest. The swirling tides below are where Alice Oswald’s epic poem, Dart, has Proteus guiding the seals out to sea, asking

Who’s this moving in the dark? Me,

. . . the shepherd of the seals,

Driving my many selves from cave to cave.

Inland the river opens out into the protected basin of Dartmouth harbour, with the town on the left and the answering village of Kingswear on the right. The latter’s houses climb uphill in shades of white, pink and cream, architecture imitating watercolour. The harbour teems with sailing ships, the masts and spars a filigree against the trees. For once an English riviera is reminiscent not of an aquatic caravan park but of ancient sailing ships.

Piracy was to the south coast of Devon what smuggling was to the north. The town’s larger-than-life mayor in the fourteenth century, John Hawley, ‘always kept the law because he made it himself’. Chaucer visited Dartmouth as inspector of customs and his pilgrims included a Dartmouth captain, who ‘of nyce conscience took he no keep’.

The church’s tower is prominent, its interior nautical in furnishings, as if built by ship’s carpenters. A ferry fusses round the same quay as was used by the Crusaders and later by a large flotilla gathered for D-Day. Above rises the palatial Edwardian building of the Royal Naval College, the shades of empire drawing inspiration from the buccaneering history of the port below.

The Dart valley wanders upstream through charming meadows past Agatha Christie’s holiday home of Greenway, high on the east bank. The tidal reach goes as far inland as Totnes. Queen Victoria called this England’s Rhine.

Irresistible force meets immovable rock at Hartland

HARTLAND QUAY

Hartland is X-certificate coast. It craves bad weather, leaden skies and tumultuous waves. Facing due west, it is the first land the Atlantic has encountered since America, and it is not pleased. The cliffs and rocks are irresistible force meeting immovable object. They are best seen in a swirling mist, disappearing and re-emerging with added menace. Hartland is always a good view, but it rages into life in a storm.

The road to the quay from inland seems headed for the end of the earth. Trees shorten to stumps, hills empty and the few farms look like desperate survivors of a climatic disaster. We pass through the village of Stoke, its tall church tower supposedly a beacon to sailors, before dipping down to the isolated manor of Hartland Abbey and on to the coast at Hartland Quay. It is an unfrequented spot.

Hartland Point, two miles to the north along the ‘iron coast’, was notorious in the days of sail. A ship failing to round it into Bideford Bay in a sou’westerly was usually doomed. Admiralty advice to sailors was, if wrecked, to stay aboard as ‘there is little or no chance of saving life by taking to the ship’s boats’. The Victorian vicar of neighbouring Morwenstow, Robert Hawker, recorded that ‘so stern and pitiless is this iron-bound coast’ that a parishioner had witnessed eighty wrecks in just fifteen miles ‘with only here and there the rescue of a living man’.

There was a Tudor harbour here, but it fell into ruin and collapsed in the nineteenth century, battered to pieces by the surf and considered not worth replacing. The settlement now comprises a single, strangely urban lane called ‘The Street’, housing the Wrecker’s Retreat pub. Opposite are a museum and rental cottages. The best views are either from the folly on the cliffs above or, especially in rough weather, from the grassy platform and lookout by the quay. There is no better place to sense the fury of sea, with the foreshore stretching on either side under the cliffs.

Hartland is England’s version of Ulster’s Giant’s Causeway, well described in a guide by a local geologist, Peter Keene. Its sedimentary mudstone and sandstone were compressed, buckled, fissured and folded into corrugations by tectonic collision some 300 million years ago. The resulting layers are embedded in the cliffs, fashioned into waves, arches, zigzags and chevrons.

Immediately north of the quay lie Warren Beach and Bear Rock, an upward stack with saw-like teeth stretching out into the waves. The rocks seem twisted in agony, piled against each other like corpses at the mouth of hell. To the south is Well Beach. Here erosion has left smooth wave-cut platforms of rippled rock sliding into the water, ideal for landing small boats. Behind it are the rock-falls of a so-called storm beach, patiently awaiting their turn to be crushed to sand. In the distance lies Screda Point, its lofty slabs of sandstone so smooth as to look man-made.

Along the tops of these cliffs clumps of thrift and sea campion cling where trees have long given up the ghost. In one thicket I heard a stonechat chirping defiance at the elements.

KYNANCE COVE

Towards Lizard Point

Kynance is picture perfect. Open heath slopes down to sandy shore. Elegant rocks do not enrage the surf, as at Hartland, but soothe it. The beach abounds in streams, rock pools and windbreaks. A discreet café causes no offence. Acquired by the National Trust in the 1990s, Kynance is perpetually posing for a photograph.

The secret of the Lizard peninsula, of which Kynance is part, lies in its geology, in ancient volcanic rock taking the form of green or red serpentine stone. This stone, unique in England, is cut and polished for jewellery and trinkets. Serpentine also yields a unique Cornish heathland, and lends a deep turquoise to the surrounding waters.

Kynance bay is divided into two beaches by Asparagus Island with its prominent Lion Rock and, to the right, by Sugarloaf Rock. They are joined to the shore by a tombolo, a sandy spit covered at high tide. Facing them on the cliff is a grassy promontory from which the best view of the whole bay is obtained. I once sat here surrounded by heather, thyme and thrift in bright sunlight after days of miserable weather and could hardly believe myself in England.

Asparagus Island from Tennyson’s look-out

It was here in 1860 that the Pre-Raphaelites Holman Hunt and Val Prinsep sat sketching Asparagus Rock on a holiday visit with Tennyson and Palgrave. Hunt wrote of looking down on ‘the emerald waves breaking with foam, white as snow, on to the porphyry rocks . . . The gulls and choughs were whirling about to the tune of their music, with the pulsing sea acting as bass.’ Palgrave was desperate lest the elderly Tennyson go too near the cliff, infuriating the poet by his attentiveness. Tennyson eventually relaxed and imagined an eagle on the rock:

He clasps the crag with crooked hands

Close to the sun in lonely lands

Ring’d with the azure world he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

The rocks compose a complete gallery of natural sculpture, formed of cones, cubes and triangles. At high tide they emerge from the water like floating mountains in an oriental print. From each angle, and especially in moonlight, they take on new shapes, as faces, volcanoes, lions and dolphins’ heads. The seaweed underwater floats like fish in shoals. Lesser rocks litter the beach, forming pools of childhood delight. This is a beach of clean sand and privacy, a monument to the variety and intimacy of England’s shore. In the distance are the cliffs of the Lizard, the country’s southernmost point.

MINACK THEATRE

Towards Logan Rock

The cliffs of Minack form the most exciting natural amphitheatre in England. In 1929 Rowena Cade, a thirty-six-year-old Derbyshire woman, came with her widowed mother to live at Porthcurno. A troupe of amateur actors were performing A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a local meadow. So entranced was Cade that she suggested next year they do The Tempest on a cliff ledge at the foot of her garden at a spot called Minack, Cornish for rocky place. A rudimentary stage was built and lighting supplied from car batteries and a wire from the house. As the moon rose on the setting that first evening, Cade knew she had found magic.

Cade and her gardeners slowly transformed the cliffside into a Greek theatre. Granite boulders were levered into place, concrete poured and timbers hauled up the slopes, Cade doing much of the work herself. The result is not just a feat of engineering but the most dramatic of theatrical backdrops. The actors perform in front of two great rocks and a backdrop of wave-capped sea. Gulls cry overhead. The birds are distracting for the audience at first, but they and the setting gradually fuse nature and drama into one experience. Only during the war did performances cease.

By the time Cade died in 1983, the Minack was an established summer festival. Companies now visit from across the world, performing mostly Shakespeare but also local favourites such as The Pirates of Penzance. I recall an Oxford student troupe returning from a summer appearance, spellbound by the experience.

The auditorium, which borders the South West Coast Path, is open daily to visitors and offers a sweeping view east over Porthcurno bay. The precipitous slope to the stage, beautiful as it may be, is not for acrophobics, giving the impression of the sea rising vertically as a giddy backdrop. In the distance is Logan Rock, a ‘rocking boulder’ of eighty tons of granite. It used to move to the touch, but was toppled by a group of drunken sailors in 1820. They were forced by local villagers to restore it, which they did, but the rocking is now harder to achieve.

Porthcurno and Logan Rock as backdrop to Minack’s drama

Among other interests, Cade was intrigued by the botanical challenge of her site, sunny most of the time and sheltered from the prevailing south-west wind. Exotics were imported to see whether they could survive the salt-laden air, planted in among the theatre’s seats and tiers. They include bird-of-paradise trees from South Africa, Californian poppies, aeoniums from the Canary Isles, agaves from Mexico and Madeiran geraniums.

The only threat to the Minack is from Cornwall’s planners. They have allowed rows of holiday homes to break the cliff horizon in almost every direction, bringing intimations of suburbia to what should be a wild, open coast. Such development could at least have been pushed a hundred yards inland.

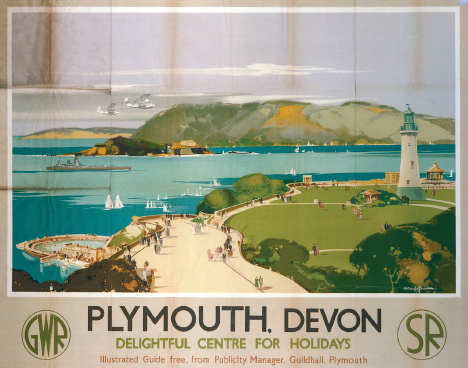

PLYMOUTH SOUND

From the Hoe

I can’t love it, I can’t hate it. The post-war devastation of Plymouth was unparalleled among English towns. What the Luftwaffe left standing, Plymouth’s city fathers set about destroying. Even where old buildings remained, as in the Barbican neighbourhood, planners forced setbacks and realignments that spoiled the rhythm of the streets and alleys. Plymouth seems a far cry from Thomas Hardy’s ‘marble-streeted town’ and nearer to Geoffrey Grigson’s post-war lament, ‘Dirty concrete rises and replaces/ Your town’s stuccoed dignities and maritime graces.’

Nor did Plymouth spare its most notable feature, the Hoe, from which generations of seafaring families had watched their ships sail, first from the Barbican and then from the naval base at Devonport. Today its Regency terrace is punctuated by a bland slab and a tower. A Ferris wheel has been deposited on the Hoe’s summit, while the descent to the waterfront is crowded with modern leisure facilities. In 2008 the council published a plan boldly proposing the removal of buildings of ‘negative quality’. They are still there.

For all that, the Hoe remains the hub round which the Plymouth landscape revolves. It ranks in England’s historical geography with the white cliffs of Dover, testified by the cluster of memorials on its summit. It was here in 1588 that Sir Francis Drake supposedly played bowls while waiting for the tide to turn before confronting the Armada, a happy tale now discredited. Below on the Barbican quayside, the Pilgrim Fathers embarked in 1620 to found the colony of New Plymouth in America, having been forced by a storm to come ashore after leaving from Dartmouth.

The Hoe remained strategically important into the seventeenth century, when Plymouth rallied to Parliament during the Civil War and was besieged for four years. On the Restoration a star-shaped citadel was built on its summit, its guns pointing both out to sea and inland over the town. Local regicides were imprisoned on Drake’s Island, a prominent rock in the Sound. This island was later converted into a naval fortress, last fitted with guns in 1942. Since then the defence ministry and Plymouth council have vied with each other in failing to find a use for it.

The view out over the Sound is refreshingly sylvan. The west side is occupied by the woods of Mount Edgcumbe, green, lush and preserved. Here in the 1550s Sir Richard Edgcumbe built a mansion to complement his ‘country’ seat up the Tamar at Cotehele. The house survived, much altered, until hit by a German incendiary bomb in the war. The seventh Earl of Mount Edgcumbe rebuilt it within the old walls in neo-Georgian style. After his death the estate passed to a succession of New Zealand relatives who dutifully returned to occupy it. The house passed to the local council in 1987.

Opposite to the east is Mount Batten, site of the first prehistoric settlement of the area. Archaeologists have revealed the possible remains of a trading post with links to Iberia and the Mediterranean. The round tower is a seventeenth-century artillery base. Mount Batten was later used for flying boats, a mode of transport now sadly almost defunct, with the Sound as an ideal landing strip. Covering its entrance is a breakwater, used to stage the British firework championships since 1997.

In the 1870s the Hoe played host to the relocated Eddystone light, known as Smeaton’s Tower, removed from the notorious rock out at sea. It now stands prominent on the slope, and can be climbed for a better view (though curiously not after 4.30 or on Sundays). Behind, at 3 Elliot Terrace, is the house that once belonged to Nancy Astor, Britain’s first sitting woman MP, who represented Plymouth after her husband’s resignation. She famously came out onto the Hoe during the blitz to dance with the sailors.

Early Great Western: flying boats over the Hoe, poster by Claude Buckle, 1938

ST MICHAEL’S MOUNT

From Newlyn

St Michael led the army of God, defended Christians against Satan and is patron saint of high places. His Cornish ‘home’ rises from the sea to gaze across Mount’s Bay towards Penzance, oozing legend and tourist appeal in equal measure. St Michael appeared to local fishermen in 495. The rock was used by the giant Cormoran, eventually slain by Jack the Giant Killer, and again by the hermit Ogrin to buy dresses for Queen Isolde. It was also the scene of yet another of King Arthur’s incessant battles. St Michael’s is a plot of land entirely surrounded by myth.

The rock was certainly an Iron Age trading post for Cornish tin. A chapel is said to have been founded here by Edward the Confessor and later given to the celebrated Normandy abbey of Mont Saint-Michel. Confusion surrounds a report in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that the rock was originally five miles inland, surrounded by sea only in 1099 after an inundation of the Penzance plain. If so it can hardly have been a prehistoric port. Either way, after the conquest it passed to the Benedictines, who founded a priory on the rock in 1135.

History has rarely left St Michael’s in peace. As a French foundation, the priory saw early dissolution by Henry V in the Hundred Years War, but it remained as a powerful fortress. It was held against the Yorkists in the Wars of the Roses and against Henry VII by the pretender, Perkin Warbeck. Elizabeth I gave it to her loyal aide, Robert Cecil, and it was later held for the king in the Civil War. It then passed to Colonel John St Aubyn, whose descendants live there to this day, under lease from the National Trust.

The mount forms a triangular profile, its rocks turning into the ramparts of the castle and priory buildings that form its summit. The stone causeway over the beach to its quay is usable only at low tide. The monastery’s military, religious and domestic ranges are reached up a winding path through richly exotic semi-tropical gardens. It is a peaceful spot with little of the ‘industrial’ tourism of its French sister at Mont Saint-Michel. Whatever the weather it seems an island of calm.

The most photogenic view of St Michael’s Mount is from the shore and the narrow streets of adjacent Marazion. I prefer a wider setting, across the bay from the lanes above Newlyn harbour. From here the whole shoreline is visible along a twenty-five-mile sweep to Lizard Point. The mount rises dark across the water in the middle distance. To the left are the uplands of Mulfra Hill, with the remains of the remarkable Iron Age village of Chysauster, which must once have traded tin through the port at St Michael’s.

Workaday Cornwall: The Mount from Newlyn harbour

In the foreground lies Newlyn, once home to a school of landscape artists and bustling with maritime commerce. The mount is thus seen rising through the masts of workaday fishing boats, surrounded by quays, warehouses, cranes and seamen’s missions.

TINTAGEL

Dark headland hovers over massive rock. Round them crash seas of a turquoise colour produced by light acting on copper embedded in slate. This slate is one of the few sure things about Tintagel. It is a place where history has conceded victory to myth. The castle’s website is stuffed with Arthur, Merlin, Guinevere, Tristan and Isolde, not to mention advertisements for £170 chain-mail tunics. The small village is surrounded by a rampart of hot-dog stalls and an outer bailey of caravan and camp sites.

The exploitation of Tintagel is not new. The link with Arthur derives from a twelfth-century cleric, Geoffrey of Monmouth, who wrote a work of fiction with the unhelpful title History of the Kings of Britain. He told of someone called Arthur, conceived at Tintagel by Uther Pendragon of Igraine, wife of the local warlord, Gorlois. This was achieved by Merlin magically transforming Uther into the form of Gorlois, and thus getting him into the castle to impregnate Igraine.

The result of this unseemly congress was a saga of romance, chivalry and tomfoolery of timeless appeal. The story consumed all Europe throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. During the Hundred Years War, Edward III had his courtiers dress as Arthurian characters, and welcomed his treacherous mother, Isabella, back to court as Guinevere. By the time Caxton printed Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur in the 1480s, the legendary monarch was a world celebrity.

As usual the Victorians trumped the pack. Tennyson and Swinburne rewrote the legends at length. The Pre-Raphaelites and William Morris added copious depictions. In 1899 a Tintagel entrepreneur built a mock-medieval hotel called Camelot on the headland overlooking the island. It now claims Ava Gardner, Noël Coward and Winston Churchill as guests who came to see ‘the birthplace of King Arthur’. Hollywood continues to bolster the genre.

There is evidence that the rock and adjoining cliff may have been occupied in the Dark Ages, possibly by a lord of the Cornish kingdom of Dumnonia. The first known castle was built by an English earl, Richard of Cornwall, in 1233, apparently to identify himself with Geoffrey’s Arthur and ingratiate himself with the locals. He found Tintagel a miserable spot and the castle was ruinous by the fourteenth century. Were it not for Geoffrey it would have been forgotten. Tintagel should thank him, not Arthur.

Arthurian Tintagel, Samuel Palmer, c. 1848

The best place from which to see Tintagel rock is from the cliffedge to the north, directly in front of the Camelot hotel – if only because no other view can avoid it. The rock is linked to the mainland by a tenuous causeway, now crossed by a footbridge. It is worth a view if only for the way it rises majestically from the sea in defiance of the elements. Some scattered ruins, enhanced by the Victorians and English Heritage, can be made out on the inland side of the island. Others on the mainland are partial reconstructions. As so often I would love more of this, to convey some sense of place and purpose.

The setting is tremendous, a vista of brutal rocks and headlands stretching in either direction along the Atlantic shore. The most vivid monument along this shore is not the castle but Tintagel church, standing wild on its cliff top defiantly gazing out to sea like a lighthouse. This is a Norman building with all the antiquity the castle lacks. It appears Roman Catholic in its fixtures and dressings, as ignorant of the Reformation as Tintagel is of the truth.

This has long been an inspiring place. The composer Arnold Bax wrote his surging tone poem, ‘Tintagel’, after a secret visit with his mistress, Harriet Cohen, in 1917. The theme is taken from Wagner’s Tristan and the words include, ‘For all my heart’s warm blood is mixed/ With surf and green-sea flame.’ A few miles to the south, the young John Betjeman likewise sat on a cliff, contemplating suicide after his poems were ridiculed by the press. He gazed over the edge where

Gigantic slithering shelves of slate

In waiting awfulness appear,

Like journalism full of hate.