Chapter 6

Getting the Word

In This Chapter

Getting text into Publisher

Getting text into Publisher

Sending text out of Publisher

Sending text out of Publisher

Forming, reforming, and deforming stories

Forming, reforming, and deforming stories

Working with story text

Working with story text

Inserting Continued notices

Inserting Continued notices

Working with table frames

Working with table frames

In this chapter, I help you look closely at two frame types: text boxes and table frames. You use text boxes to place and manage text in your publication. Microsoft Publisher 2007 has some special features to help you manage text frames across pages: the capacity to make text flow automatically between linked frames, and stories, which are just blocks of text managed as a single entity. You can even place Continued notices (Continued on Page and Continued from Page) in your publication to help readers follow a story that begins on one page and continues on another.

In addition to providing regular text boxes, Publisher 2007 has two other types of frames for holding text: table frames and WordArt frames. If you’ve worked in a spreadsheet program, such as Microsoft Excel, or used a word processor that offers a table feature, such as Microsoft Word, the table frames features in Publisher 2007 should look familiar to you. If not, you can find out what you need to know about table frames at the end of this chapter. You can also create a shape, select it, and start typing. Like magic, your text then appears in the shape.

WordArt frames enable you to create fancy text by using WordArt to manipulate type. I cover WordArt in Chapter 9 because this type of frame is more commonly used for short pieces of decorative text, rather than for the longer text that comprises most people’s publications.

Getting Into the Details of Text Boxes

If you’re accustomed to creating text in other computer programs, you may find it odd that you can’t just begin typing right away in a Publisher publication. You must first create a text box to tell the program where to put your text. Not that this is in any way a big deal — Chapter 5 shows you how easy creating a text box is: You simply click the Text tool in the toolbox and then click and drag to create the text box.

After you create a text box, you can fill it in one of three ways:

Type text directly into the text box.

Type text directly into the text box.

Paste text from the Clipboard.

Paste text from the Clipboard.

Import text from your word processor or text file.

Import text from your word processor or text file.

The next few sections give you a bit more detail on each technique.

Typing text

Publisher offers a complete environment for creating page layouts, so you soon discover that you can write your text in text boxes with little trouble. Admittedly, Publisher isn’t the most capable text creation tool, and it doesn’t have all the bells and whistles you would expect to find in your word processor, but it has been updated to integrate more closely with the Microsoft Office suite of applications. The idea is to let you leverage skills acquired from other Microsoft programs, such as Microsoft Word.

Menus and toolbars: You may recognize the File, Edit, View, Insert, Format, Tools, and Help menus on the menu bar. Also, the New, Open, Save, Print, Cut, Copy, Paste, Format Painter, Undo, Redo, Show/Hide ¶, and Microsoft Publisher Help (it’s Microsoft Word Help in Word) buttons from, say, Word 2003 should all seem familiar.

Menus and toolbars: You may recognize the File, Edit, View, Insert, Format, Tools, and Help menus on the menu bar. Also, the New, Open, Save, Print, Cut, Copy, Paste, Format Painter, Undo, Redo, Show/Hide ¶, and Microsoft Publisher Help (it’s Microsoft Word Help in Word) buttons from, say, Word 2003 should all seem familiar.

AutoCorrect: This feature lets you automatically fix some common errors, such as correcting two initial capitals or automatically capitalizing the names of days.

AutoCorrect: This feature lets you automatically fix some common errors, such as correcting two initial capitals or automatically capitalizing the names of days.

Spell Check: This feature automatically checks spelling as you type; it flags any misspelled or repeated words by underlining them.

Spell Check: This feature automatically checks spelling as you type; it flags any misspelled or repeated words by underlining them.

If you’re used to typing on a typewriter or in a word processor, you may be used to doing some things that you shouldn’t do in Publisher — or in any page layout program — when you enter text.

Here’s a list of things not to do when you’re entering text:

Don’t press Enter to force a line ending. Pressing Enter tells the program that you’ve reached the end of a paragraph. If you press Enter at the end of every line, you cannot format the lines of your paragraph as a unit, which can be a bad thing. When you get to the end of a line of text, let Publisher word-wrap the text to the next line for you (which it does automatically). Press Enter only to end a paragraph or a short, independent line of text (such as a line in an address).

Don’t press Enter to force a line ending. Pressing Enter tells the program that you’ve reached the end of a paragraph. If you press Enter at the end of every line, you cannot format the lines of your paragraph as a unit, which can be a bad thing. When you get to the end of a line of text, let Publisher word-wrap the text to the next line for you (which it does automatically). Press Enter only to end a paragraph or a short, independent line of text (such as a line in an address).

Note: If you need to force a line break without creating a new paragraph, press Shift+Enter. This keystroke creates a soft carriage return (;) and places the symbol at the end of the line.

Don’t press Enter to create blank lines between paragraphs. Publisher 2007 has a much better way to create spaces before and after paragraphs: Choose Format⇒Paragraph from the main menu and then adjust the Line Spacing settings in the Paragraph dialog box that appears.

Don’t press Enter to create blank lines between paragraphs. Publisher 2007 has a much better way to create spaces before and after paragraphs: Choose Format⇒Paragraph from the main menu and then adjust the Line Spacing settings in the Paragraph dialog box that appears.

Don’t insert two spaces between sentences. Use just one. It makes your text easier to read.

Don’t insert two spaces between sentences. Use just one. It makes your text easier to read.

Don’t press the Tab key or spacebar to indent the first lines of paragraphs. Instead, use the paragraph indent controls, explained in Chapter 7. These controls offer much more flexibility than tabs.

Don’t press the Tab key or spacebar to indent the first lines of paragraphs. Instead, use the paragraph indent controls, explained in Chapter 7. These controls offer much more flexibility than tabs.

Don’t try to edit or format your text as you go. It’s much more efficient to complete all your typing first, your editing second, and your formatting last.

Don’t try to edit or format your text as you go. It’s much more efficient to complete all your typing first, your editing second, and your formatting last.

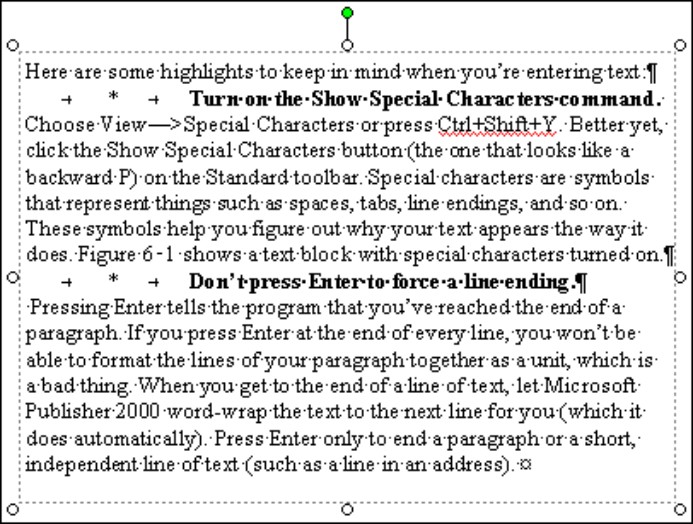

In addition to all these don’ts, I want to add a definite do: Do turn on the Show Special Characters command. Special characters are symbols that represent elements such as spaces, tabs, and line endings. These symbols help you figure out why your text appears the way it does. To turn on this feature, choose View⇒Special Characters or press Ctrl+Shift+Y. Better yet, click the Show Special Characters button (the one that looks like a backward P) on the Standard toolbar. Figure 6-1 shows a text block with special characters turned on.

|

Figure 6-1: Special characters in text boxes help you follow what’s going on. |

|

If any of the suggestions in this section seem new to you, I recommend that you check out one of the typographical style books mentioned near the end of Chapter 2, in the section about desktop style resources. I’m especially fond of The PC Is Not a Typewriter, by Robin Williams (Peachpit Press). If you’re working in a specific word processing program, you may also want to pick up the For Dummies book on that program.

As you type, your text begins filling the text box from left to right and from top to bottom. If the text box isn’t large enough to accommodate all your text, you eventually reach the bottom of the text box. When you type more text than can fit into a text box, the extra text moves into the invisible overflow area. You can type blindly in that overflow area; the program keeps track of everything you type. If you’re like most people, though, you probably want to see what you’re typing as you type it.

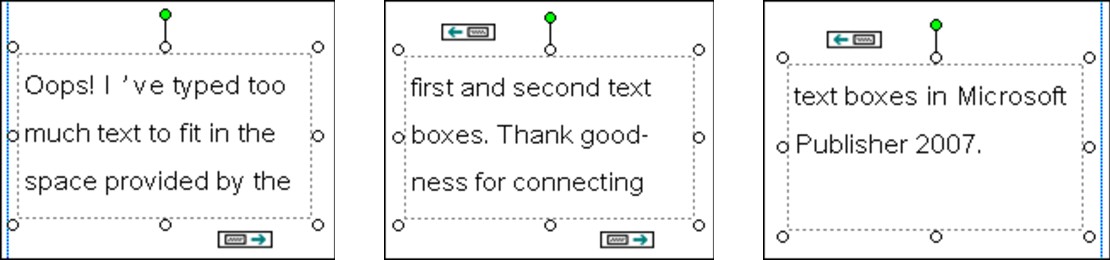

The Text in Overflow indicator alerts you when you type more text than can fit into the current text box. The indicator is located in the lower-right corner of the text box. (Figure 6-2 shows you a text box with the Text in Overflow indicator doing its thing.) If you see the indicator at the bottom of a text frame, you know that the text box isn’t large enough to contain the text.

“Good enough,” you might say, but what can you do to be able to see what you type again? You have several options, although the most straightforward method is to simply enlarge the text box by clicking the text box to select it, placing your mouse pointer on one of the round selection handles, and dragging the cursor to enlarge the text box. (If you’re still confused, Chapter 5 explains this process in even more detail.) With a larger text box, the text in the overflow area has room to spread out (and automatically appears). You can also use the Create Text Box Link button to link text boxes for autoflowing, as described later in this chapter, in the section “Autoflowing text.”

|

Figure 6-2: Text box with text in the overflow area. |

|

Pasting text from the Clipboard

You can paste text into a Publisher publication by using the Windows Clipboard. Here’s how to do it:

1. In Publisher, select the Text Box tool on the Objects toolbar and draw a text box on the page (if you don’t have a text box created).

2. Highlight the text in the program containing the text that you want to use.

3. Choose Edit ⇒Copy or press Ctrl+C.

4. In your Publisher publication, click the Select Objects tool on the Objects toolbar, and click in a text box to set the insertion point at the position where you want your text to be pasted.

Feel free to flip over to Chapter 5 to find out how to create text boxes.

5. Choose Edit ⇒Paste or press Ctrl+V.

If you didn’t set an insertion point in Step 4 or didn’t have a text box selected, Publisher creates a new text box and imports the copied text into that text box. In most cases, the text box that Publisher creates isn’t the size and shape you want, and it isn’t in the place you want it to be. Save yourself some time by creating the text box before you paste.

If you can copy formatted text successfully to the Windows Clipboard, the text should be pasted correctly into your text box. For more information about using the Windows Clipboard, see Chapter 5.

If the text on the Clipboard can’t fit in the text box you selected, the program performs an autoflow operation. First, it displays a dialog box informing you that the inserted text doesn’t fit into the selected text box and asks whether you want to use autoflow. I talk about autoflow in more depth later in this chapter, in the section “Autoflowing text.”

Importing text

As an alternative to using the Windows Clipboard to import text into a text box, you can choose Insert⇒Text File to move text between your word processor and Publisher. (The process is rather more complicated than my description here lets on — the text does a bit of a two-step, in that it first gets converted to an intervening text file and is then brought into Publisher.)

Before you choose Insert⇒Text File, you must save your text to a file by using a format that Publisher can read. Fortunately, Publisher accepts many different file formats, including the ones in this list:

All Publisher files (No surprise here!)

All Publisher files (No surprise here!)

Plain text (ASCII) or plain formatted text (RTF)

Plain text (ASCII) or plain formatted text (RTF)

Although most programs should at least be able to save text as plain, or ASCII, text, ASCII should be your last resort because ASCII text uses no formatting. If you save a text file in ASCII format, the file loses all formatting (such as bold, italic, or underlining). Try to avoid this option.

Single File Web Page (*.htm, *.html)

Single File Web Page (*.htm, *.html)

Rich Text Format, or RTF: In RTF (the Microsoft text-based, formatted text interchange format), ASCII characters are saved in your file, along with special commands to indicate formatting information — such as bold, italic, or underlining. You don’t need to concern yourself with these formatting commands; you need to know only that the RTF text format saves formatting on text.

Rich Text Format, or RTF: In RTF (the Microsoft text-based, formatted text interchange format), ASCII characters are saved in your file, along with special commands to indicate formatting information — such as bold, italic, or underlining. You don’t need to concern yourself with these formatting commands; you need to know only that the RTF text format saves formatting on text.

Microsoft Word 2007 (and other versions for Windows or the Macintosh)

Microsoft Word 2007 (and other versions for Windows or the Macintosh)

Recover Text from Any File

Recover Text from Any File

WordPerfect 5.x and 6.x

WordPerfect 5.x and 6.x

Microsoft Works

Microsoft Works

If your word processor doesn’t save to one of these file formats automatically, check to see whether it offers an Export command, which can translate your word processor file into a form that Publisher understands.

Okay, you save whatever you want to import into your Publisher publication to a file using an acceptable format. Now what? To import the text file into Publisher, follow these steps:

1. Locate the text box into which you want to import the text, and then position the insertion point inside the box where you want the text to appear.

2. Choose Insert ⇒Text File.

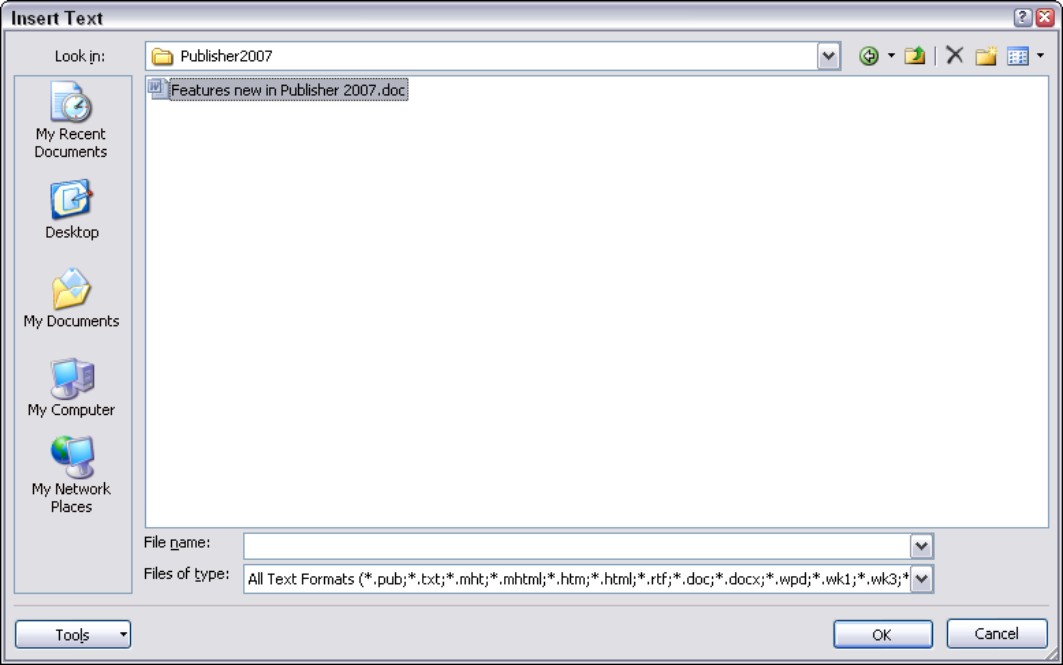

The Insert Text dialog box, shown in Figure 6-3, appears.

3. Locate the file you want, highlight it, and then click OK.

After a moment, the text appears in the selected text box.

|

Figure 6-3: The Insert Text dialog box displays a selected DOC file. |

|

Here are some tips for using the Insert Text dialog box:

If you can’t find your text file, make sure that you selected the correct import filter from the Files of Type drop-down list.

If you can’t find your text file, make sure that you selected the correct import filter from the Files of Type drop-down list.

To see all files in a folder, select All Text Formats in the Files of Type drop-down list.

To see all files in a folder, select All Text Formats in the Files of Type drop-down list.

If the file still doesn’t appear, you’re looking in the wrong place. Use the Look In drop-down list, at the top of the dialog box, to switch to another location.

If the file still doesn’t appear, you’re looking in the wrong place. Use the Look In drop-down list, at the top of the dialog box, to switch to another location.

If not all the imported text can fit in the selected text box, the program opens a dialog box asking whether you want to autoflow the rest of your text into other text boxes. (I present more information on autoflowing text later in this chapter, in the section “Autoflowing text.”)

If not all the imported text can fit in the selected text box, the program opens a dialog box asking whether you want to autoflow the rest of your text into other text boxes. (I present more information on autoflowing text later in this chapter, in the section “Autoflowing text.”)

You can view the contents of a text file without importing the file into your publication. Choose File⇒Open (or press Ctrl+O) to access the Open dialog box, click the down arrow next to the Files of Type text box, and select All Text Formats. Find the file you want and click Open. Publisher opens the text or word processor file as a full-page publication that offers the requisite number of pages filled with full-page text boxes. Keep in mind that, depending on your computer and the size of the document you’re opening, this process can take a while to complete.

|

Figure 6-4: Inserting a text file by using the context-sensitive menu in the text box. |

|

Exporting text

Hey, here’s something you already know how to do! Just as easily as you can transfer text that’s created elsewhere into Publisher, you can also send text out of the program so that other computer programs can use the text. (Isn’t it nice when programs share? I feel like I’m back in kindergarten.) Just as bringing text into Publisher is called importing, sending text out is called exporting.

Publisher provides two ways to export text:

Choose Edit

⇒Copy to copy selected text from Publisher to the Windows Clipboard, and then switch to another Windows program and choose Edit

⇒Paste to paste it directly into that program. If the program you’re pasting text into uses the Ribbon, choose Paste on the Clipboard group of the Home tab.

Choose Edit

⇒Copy to copy selected text from Publisher to the Windows Clipboard, and then switch to another Windows program and choose Edit

⇒Paste to paste it directly into that program. If the program you’re pasting text into uses the Ribbon, choose Paste on the Clipboard group of the Home tab.

Choose File

⇒Save As to send all text in a publication to a text file or word processor file in one of the formats listed in the preceding section. Publisher opens a dialog box informing you that the file type you selected supports only text. Click OK to save it anyway.

Choose File

⇒Save As to send all text in a publication to a text file or word processor file in one of the formats listed in the preceding section. Publisher opens a dialog box informing you that the file type you selected supports only text. Click OK to save it anyway.

It’s probably unfortunate that Publisher (still!) doesn’t have an Export command on its File menu, as other desktop publishing programs do. Then I could make believe that there’s more to know about exporting text from the program than there really is. It’s almost too easy.

Word up

In the past, the folks at Microsoft went to a lot of trouble to make typing and editing text in Publisher as easy as typing and editing text in Microsoft Word. One way they did that was by maintaining a remarkable similarity between the toolbars in Publisher and in the available versions of Word.

My, how times have changed. Microsoft Word 2007 was released with its new Ribbon feature, and now we have to unlearn the old way of doing things in Word and learn the new ways. If you went to the trouble of learning them, you may want to stick with Word 2007 when you want to create and edit text, rather than create and edit text within Publisher. I do. Let’s face it: Publisher is an excellent publication design and layout program, but a word processor it isn’t.

Inserting a Word document

If you have an existing Microsoft Word document that you want to include in your publication, follow these steps:

1. Locate the text box into which you want to import the Word file, and then position the insertion point inside the box where you want the text to appear.

2. Choose Insert ⇒Text File.

The Insert Text dialog box appears. (Refer to Figure 6-3.)

3. Select All Text Formats from the Files of Type drop-down list.

4. Locate your Word document, highlight it, and click OK.

After a moment, the text from your Word document appears in the selected text box. Breathe a sigh of relief as you realize that you don’t have to reformat all that text. Your Word document retains its formatting when you import it into Publisher.

Using Word to edit your text

If, after bringing your Word document into Publisher, you need to make changes, you don’t have to launch Word, open the Word document, save your changes, close Word, and import the document all over again. And, you don’t have to edit the text in Publisher, either. Just tell Publisher that you want to use Word to edit the text contained in the current text box:

1. Click inside the text frame that contains the text you want to edit.

2. Choose Edit ⇒Edit Story in Microsoft Word.

Word leaps (or crawls, depending on your computer) onto the screen, replete with your Publisher text.

3. Edit the text to your heart’s content.

4. Choose File ⇒Close & Return To <your publication name>.

If you’re lucky enough to have Word 2007 installed on your computer, you may have noticed by now that it has no File menu. Just click the Office Button, in the upper-right corner of the Word window. You see the Close & Return To <your publication name> menu choice at the bottom of the menu.

Word wanders off to whatever hiding place it occupies when you aren’t using it, and your publication, including the edits made in Word, returns to the screen. (Try to refrain from doing a victory dance if anyone is watching.)

Using part of a Word document

The technique of inserting a text file works well for bringing an entire Microsoft Word document into a publication, but what do you do if you want to use only part of a Word document? You copy and paste, of course! Follow these steps:

1. Launch Word and open the document that contains the text you want to place into your publication.

2. Use your favorite text selection technique to highlight some text.

3. Choose Edit ⇒Copy, press Ctrl+C, or click the Copy button on the Standard toolbar.

If you use Word 2007, you can just click the Copy button in the Clipboard section of the Home tab.

4. Switch to the Microsoft Publisher 2007 window by clicking its button on the Windows taskbar.

If the Windows taskbar isn’t visible, you can switch applications by pressing Alt+Tab. Hold down the Alt key and press Tab until the Microsoft Publisher 2007 icon is highlighted in the Cool Switch box that appears. Release both keys.

5. Click in the text box at the location where you want to insert the text from the Word document.

If the text box is empty, click anywhere inside the text box.

6. Choose Edit ⇒Paste, press Ctrl+V, or click the Paste button on the Standard toolbar.

The text from the Word document appears in the selected text box as if by magic. (Gotta love that copy-and-paste operation.)

Let Me Tell You a Story

In its simplest form, a Publisher story is a block of text that exists in a single, self-contained text box. When you add large amounts of text to a publication, you often have text that doesn’t fit in a single text box. In these cases, the traditional publishing solution is to jump (continue) each story to other pages. Jumps are extremely common in newspapers and magazines: How often each day do you see lines that read “Continued on page 3” or “Continued from page 1”?

The capability to jump a particular story between text boxes and pages is one of the best arguments for using Publisher rather than a word processing program. Although most word processing programs deal with all the text in a file as one big story, Publisher excels at juggling multiple stories within a single publication. For example, you can begin four stories on page 1 and then jump half those stories to page 2 and the other half to page 3. At the same time, you can begin separate stories on pages 2 and 3 and jump each of those stories to any other page. If there’s not enough room on a page to finish a story that you already jumped from another page, you can jump the story to another page and then another and another. The sky (or maybe the forest) is the limit.

Forming, reforming, and deforming stories

To enable a story to jump across and flow through a series, or chain, of several text boxes, you connect those text boxes to each other in the order that you want the story to jump and flow. A chain of connected text boxes can exist on a single page or across multiple pages. You can even connect text boxes that are in the scratch area (the gray work area surrounding your page) and then later move those text boxes to your publication pages.

How and when you connect text boxes depends on your situation:

If you haven’t yet typed or imported text: You can manually connect empty text boxes to serve as a series of ready-made containers for that text. When you then type or import your text, it automatically jumps and flows between text boxes, like water jumps and flows between the separate compartments in a plastic ice-cube tray. (Just remember not to put your Publisher files in the freezer.)

If you haven’t yet typed or imported text: You can manually connect empty text boxes to serve as a series of ready-made containers for that text. When you then type or import your text, it automatically jumps and flows between text boxes, like water jumps and flows between the separate compartments in a plastic ice-cube tray. (Just remember not to put your Publisher files in the freezer.)

If you’re typing text in Publisher and don’t know how much text you’ll have: You can manually connect to new text boxes as you run out of room in each current text box.

If you’re typing text in Publisher and don’t know how much text you’ll have: You can manually connect to new text boxes as you run out of room in each current text box.

If you’re importing text and there’s not enough room to fit it in the current text box: You can use the program’s autoflow feature to help connect your text boxes. You can even have Publisher draw new text boxes and insert new pages as needed to fit all the text.

If you’re importing text and there’s not enough room to fit it in the current text box: You can use the program’s autoflow feature to help connect your text boxes. You can even have Publisher draw new text boxes and insert new pages as needed to fit all the text.

The next few sections show you how to best handle each of these situations.

Connecting text boxes

When you select a text box, you may see one of several items attached to the top or bottom of the text box. The Text in Overflow indicator (refer to Figure 6-2) lets you know that the text doesn’t fit in the text box and has, well, overflowed. The appearance of either the Go to Next Text Box button or the Go to Previous Text Box button is an indication that the selected text box is already connected to at least one other text box. Clicking one of these buttons moves the insertion point to the next or previous connected text box in the chain.

Here’s how to connect a text box to another text box:

1. The easiest way to create linked text boxes is to create a series of text boxes first. Select the Text Box tool on the Objects toolbar and draw text boxes of the number and size that you estimate you need.

You might need to modify the number or sizes of text boxes later, but it’s helpful to begin with a series already created.

2. Click a text box to select it.

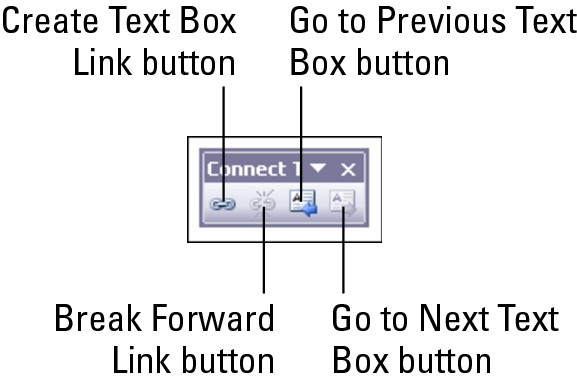

The Connect Text Boxes toolbar appears next to the Standard toolbar.

If the Connect Text Boxes toolbar is being stubborn and doesn’t show up when you click a text box, you can force the toolbar to appear by choosing View⇒Toolbars⇒Connect Text Boxes from the main menu.

3. Click the Create Text Box Link button on the Connect Text Boxes toolbar.

The Text Box Link Button looks exactly like three links in a chain.

The mouse pointer changes from a standard arrow pointer to a cute little pitcher pointer, bearing a downward-pointing arrow. As you move over an empty text box, the pitcher tilts, and the arrow points to the right. The metaphor that Publisher is using is that you’re pouring text from one text box to another. (It could be worse. In earlier days, programs often used a loaded-gun icon.)

By the way, anytime you accidentally click the Create Text Box Link button, you can press the Esc key or just click away from a text box to get rid of the pitcher pointer.

4. After clicking the Create Text Box Link button in Step 2, click the empty text box to which you want to connect the first text box. The text “pours” into the text box, filling it until it overflows.

5. To link additional text boxes, click the Create Text Box Link button again, and then click the next empty text box (even one on another page) to which you want to connect in the sequence.

The pitcher pointer tips sideways, drains its text, and reverts to a normal pointer.

The two text boxes are now connected; any text in the first text box’s overflow area appears in the second text box. Also, as you type or enter additional text into the first text box, it pushes extra text into the second text box. To create a chain of more than two linked text boxes, repeat the preceding steps. If a chain is empty, you can link another chain to its first text box to create the combination of the two chains.

As you might guess, you can connect only text boxes. If you select a table frame or a picture frame, you don’t see the Connect Text Boxes toolbar. Also, you can’t connect a text box that’s already connected to some other text box or a text box that has some text in it already. If you try to do this, Publisher displays a message box informing you that the text box must be empty.

After you connect text boxes, extra buttons appear at the top and/or bottom of each text box when the text box is selected. Figure 6-5 shows examples of three connected text boxes on a page and in sequence. Notice that when the middle text box is selected, two buttons are attached to it: the Go to Previous Text Box button on top and the Go to Next Text Box button on the bottom. Think of the text boxes in Figure 6-5 as three separate figures, though: If you try to select all three text boxes at the same time on your screen, you see the text boxes selected as a group with only a single Group Objects button.

|

Figure 6-5: Three connected text boxes. |

|

Don’t worry too much about connecting text boxes in the proper order the first time around. After you connect text boxes, you can disconnect and rearrange them quite easily. Later in this chapter, the “Rearranging chains” section tells you how.

Moving among the story’s frames

One of the first issues to consider when you work with multiple-text-box story text is how best to move among the story’s text boxes — and how to know which text box follows which! You can move easily and reliably between connected text boxes by using either the mouse or the keyboard. Both methods are easy.

Use one of these two methods to move between connected frames by using the mouse:

To move backward in the sequence: Click the Go to Previous Text Box button.

To move backward in the sequence: Click the Go to Previous Text Box button.

To move forward in the sequence: Click the Go to Next Text Box button.

To move forward in the sequence: Click the Go to Next Text Box button.

These two buttons are shown in Figure 6-5. The arrow button at the top of the text box is the Go to Previous Text Box button; the arrow button at the bottom is the Go to Next Text Box button. The first text box in a chain has no Go to Previous Text Box button, whereas the last text box has no Go to Next Text Box button.

You can also use the Go to Previous Text Box and Go to Next Text Box buttons on the Connect Text Boxes toolbar. They’re the second-to-last and last buttons on the toolbar, respectively. Figure 6-6 shows the Connect Text Boxes toolbar.

Use one of these methods to move between connected text boxes by using the keyboard:

To move to and select the chain’s next text box: Press Ctrl+Tab from a connected text box (that’s selected).

To move to and select the chain’s next text box: Press Ctrl+Tab from a connected text box (that’s selected).

To

move to and select the chain’s previous text box: Press Ctrl+Shift+Tab from a connected text box (that’s selected).

To

move to and select the chain’s previous text box: Press Ctrl+Shift+Tab from a connected text box (that’s selected).

|

Figure 6-6: The Connect Text Boxes toolbar. |

|

If your connected text boxes are full of text, you can also use many of the keyboard shortcuts for navigating text (listed in Chapter 7) to move between connected text boxes. If your insertion point is on the last line of text in a connected text box, for example, you can press the down-arrow key to move to (and select) the chain’s next text box.

Autoflowing text

Publisher uses an autoflow feature to help you fit long text documents into a series of linked text boxes. This feature is handy for automatically managing the flow of text among pages of your publication. To autoflow text into a set of linked text boxes, you select the first text box in the chain. When you insert (or copy) text into the text box, Publisher fills the connected text boxes, beginning with the text box you selected, with the inserted text. If the inserted text fits in the selected text box or chain of text boxes, you’re done.

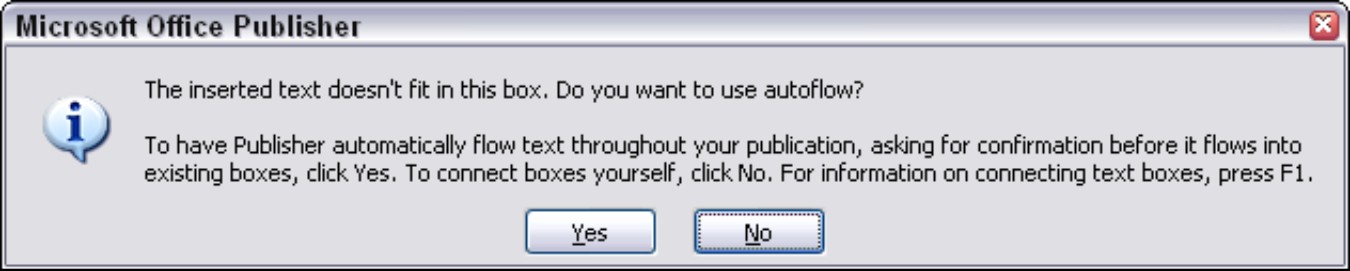

If not all the text fits into the first text box or the set of linked text boxes, Publisher displays the message box shown in Figure 6-7. Click Yes to autoflow your text, or click No to put the text into the overflow area of the first text box. Publisher then proceeds to the next text box in the sequence and again asks your permission to autoflow text to that text box. Publisher continues posting this message box with every additional text box it requires.

|

Figure 6-7: Publisher asks whether to use autoflow. |

|

If you don’t have enough linked text boxes to take care of the incoming text, the autoflow process continues: Publisher autoflows the extra text into the first empty or unconnected text box it can find or, failing that, the first text box of any empty, connected series of text boxes that exist in your publication. At each new text box, the program asks your permission to use that text box.

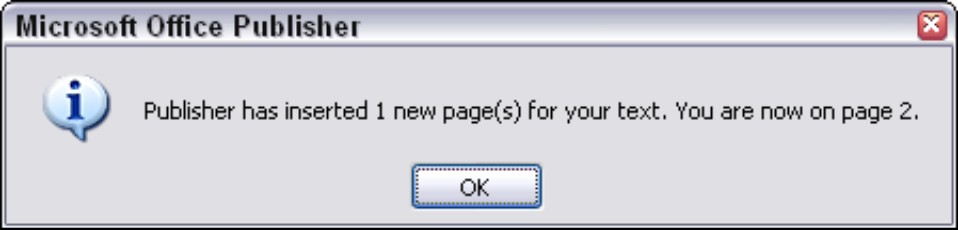

Wait — there’s more! If no empty text boxes are available, Publisher displays a third message box that asks whether you want to create additional pages at the end of your publication and fill those pages with full-page text boxes until the imported text has been placed. If you click Yes, Publisher 2007 continues flowing the story to the end, creating new pages and full-page text boxes as required. At the end of this process, the program displays a dialog box that tells you the number of new pages created and your current page location, as shown in Figure 6-8.

|

Figure 6-8: Publisher tells you how many pages it created. |

|

The autoflow process is a lot more complex to explain than it is to do. I find it natural, efficient, and well thought out; I doubt that it will give you pause or worry.

Rearranging chains

When you rearrange a chain, you have to tackle two tasks: Temporarily break the chain (disconnecting two text boxes in the chain) at the point at which you want to begin rearranging, and then reconnect the text boxes in the order you want.

Suppose that you have a chain, A-B-C-D, and you plan to add the text box X between text boxes B and C, to make the chain A-B-X-C-D. Follow these steps to rearrange the chain:

1. Click text box B to select it.

2. Click the Break Forward Link button (the second button from the left; refer to Figure 6-6) on the Connect Text Boxes toolbar.

If the Connect Text Boxes toolbar doesn’t appear when you click text box B, choose View⇒Toolbars⇒Connect Text Boxes from the main menu. You now have two chains: A-B and C-D.

3. Click the Create Text Box Link button (the first button on the left; refer to Figure 6-6) on the Connect Text Boxes toolbar.

Text box B is still selected, and the mouse pointer turns into that cool pitcher again.

4. Click text box X.

Now you have chains A-B-X and C-D.

5. Click the Create Text Box Link button on the Connect Text Boxes toolbar.

Text box X is still selected.

6. Click text box C.

Now you have one chain: A-B-X-C-D.

Voilà — you’re ready to go into the chain-repair business!

Text box X in this example can be an empty, unconnected text box or an empty, connected text box that’s the first text box in another chain — no surprise there. Because you’re rearranging a chain, however, text box X also can be any empty text box that was, but is no longer, an original part of the current chain. For example, if you disconnect text boxes B and C in the chain A-B-C-D, you can then click text box D to make it the third frame in the chain A-B-D-C.

If you try to type in an empty, connected text box that isn’t the first text box in a chain, Publisher informs you that this text box is part of another chain and asks whether you want to begin a new story at this point in the chain. Click OK to have the program disconnect that text box from the preceding text box in the chain. Any text boxes farther down the chain are now part of the new story.

After you know how to break a chain temporarily to rearrange it, permanently breaking a chain is easy. Just select the text box that you want to be the last in the chain and click the Break Forward Link button on the Connect Text Boxes toolbar. All text that follows in the next text boxes disappears from those text boxes and becomes overflow text for the last text box in the sequence. You can place the text where you want it at a later time when you connect this last text box to another text box.

Deleting stories

Connecting text boxes makes accidental text deletions a little less likely. Unfortunately, it also makes intentional deletions a little more difficult. Life is full of trade-offs!

When you delete a story’s only text box, the story text has nowhere else to go, so it gets wiped out along with the text box. When you delete a text box from a multiple-text-box story, however, the story text has somewhere it can go: into the other text boxes in the chain. Publisher is also nice enough to mend the chain for you. If you have the chain A-B-C and you delete text box B, for example, the program leaves you with the chain A-C.

If you really want to delete multiple-text-box story text, follow these steps:

1. Click any text box in the story and choose Edit ⇒Select All or press Ctrl+A.

2. Press the Delete or Backspace key.

The entire story is deleted without deleting the text boxes.

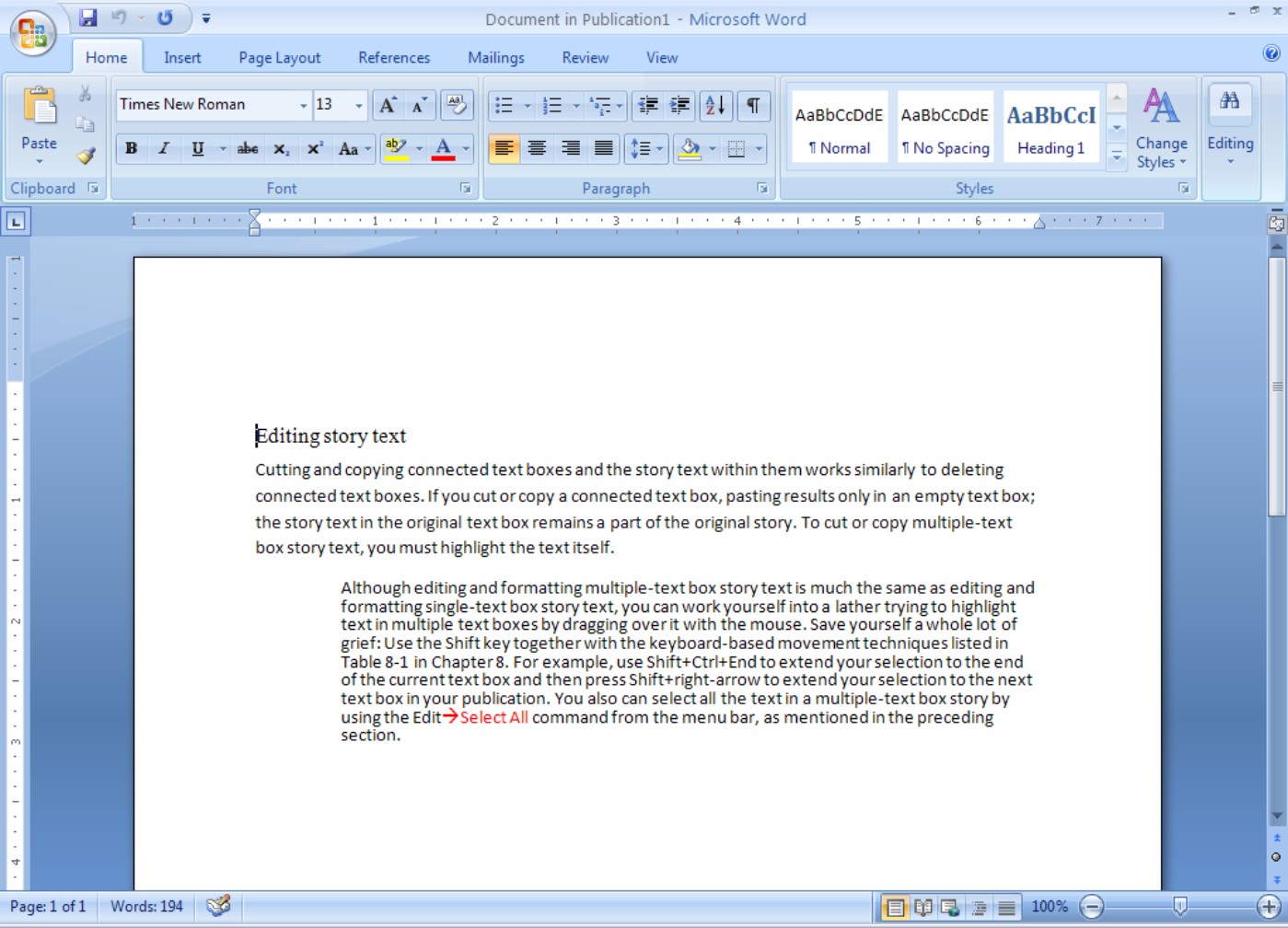

Editing story text

Cutting and copying connected text boxes and the story text within them work similarly to deleting connected text boxes. If you cut or copy a connected text box, the pasting action results in only an empty text box; the story text in the original text box remains a part of the original story. To cut or copy multiple-text-box story text, you must highlight the text itself.

Although editing and formatting multiple-text-box story text is much the same as editing and formatting single-text-box story text, you can work yourself into a lather trying to highlight text in multiple text boxes by dragging over it with the mouse. Save yourself a whole lot of grief: Use the Shift key together with the keyboard-based movement techniques listed in Table 7-1 (over in Chapter 7). For example, press Shift+Ctrl+End to extend your selection to the end of the current text box, and then press Shift+right arrow to extend your selection to the next text box in your publication. You also can select all text in a multiple-text-box story by choosing Edit⇒Select All from the menu bar, as mentioned in the preceding section or press Ctrl+A.

Select All is helpful for other processes too — for example, for deleting the entire text in a story. (Maybe you want to place a new version of the story in your publication.) Or, perhaps you want to edit your story in a word processor: You can use Select All to select the story and then export the story to a text or word processor file, open your word processor, open the file, and make your edits.

Adding Continued notices

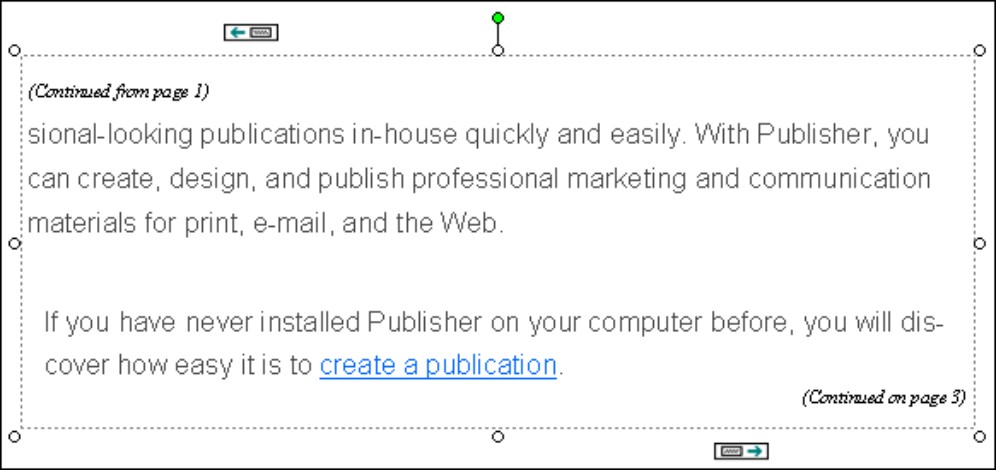

Publisher offers a feature to help readers locate the next and previous frames in a story in your publication: Continued notices. Publishing professionals sometimes refer to these handy guidance devices as jump lines. They come in two types: a Continued from Page notice tells readers where the story left off; a Continued on Page notice tells readers where the story continues.

Publisher manages Continued notices for you as an automated feature. You must manually insert and delete Continued notices to get things rolling, but after you set them up, Publisher keeps them up to date as your story grows (or shrinks) to new pages. Publisher even keeps the Continued notices up to date even when a text box is manually moved to a different page. To create a Continued notice, just right-click a linked text frame, choose Format Text Box from the context-sensitive menu, and select the Text Box tab in the Format Text Box dialog box. Select or deselect the Include Continued on Page and Include Continued from Page check boxes to turn the notices on or off, respectively, for the selected text box. When you click OK, the program places the notices in your text box. Figure 6-10 shows you an example.

Publisher displays Continued notices only when it makes sense to display them. A Continued on Page notice is displayed only if the current story jumps to another text box on another page. A Continued from Page notice is displayed only if the current story jumps from a previous text box on another page. If you modify a story in such a way that a Continued notice no longer makes sense, the program automatically hides that notice.

|

Figure 6-9: Editing a Publisher story in the Microsoft OLE server. |

|

|

Figure 6-10: A text box with Continued notices. |

|

When a Continued notice is displayed, it always contains the proper page reference. If you move or delete the next text box in a chain or add or remove pages between connected text boxes, Publisher adjusts the page reference automatically; it certainly is smart in its handling of Continued notices!

If you don’t like the wording of a Continued notice, you can edit it the same way you edit any other text. For example, you can change a Continued on Page notice to read “See page x” or “I ran out of room here, so I stuck the rest of the story on page x.” You can even add multiple lines to a Continued notice by pressing Enter while the insertion point is in the Continued notice, which is an improvement over earlier versions of the software. If you pressed Enter in a Continued notice in an earlier version, your computer just beeped at you. And, although you can add multiple lines to a Continued notice, you have to be careful not to type more than a full line of text on any of those lines. If you add so much text to a Continued notice that it no longer fits on one line, some of the text disappears.

Aligning Your Text with Table Frames

As you discover in Chapter 7, you can use tab stops and tabs in paragraphs to create tables in text boxes. You can use a more elegant method, however — table frames — to create a predefined grid of columns and rows that automatically aligns your text perfectly, and keeps it perfectly aligned. Table frames are so easy to create and manage that it makes little sense not to use them throughout your publication whenever you need tabular displays.

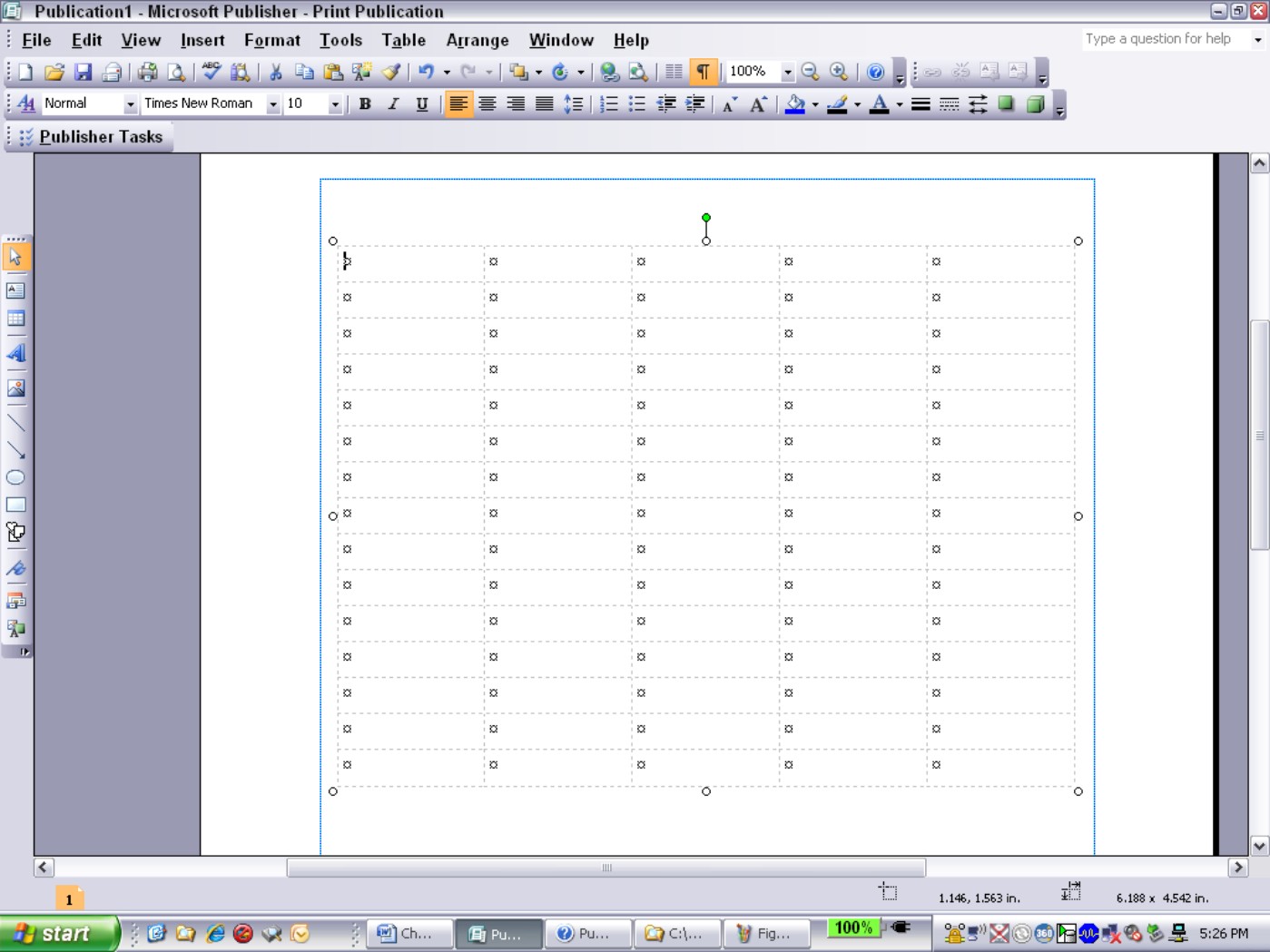

Figure 6-11 shows you how a plain, unformatted table frame might look after you create it. You can tell by the selection handles that the table frame is selected.

|

Figure 6-11: A blank, five-column table. |

|

Here are some important concepts to know about table frames:

A table frame’s selection handles are displayed only when the frame is selected — and they’re never printed.

A table frame’s selection handles are displayed only when the frame is selected — and they’re never printed.

If you can’t see gridlines on-screen, choose View⇒Boundaries and Guides or press Ctrl+Shift+O. You can hide gridlines by choosing View⇒Boundaries and Guides again.

If you can’t see gridlines on-screen, choose View⇒Boundaries and Guides or press Ctrl+Shift+O. You can hide gridlines by choosing View⇒Boundaries and Guides again.

If you choose a table format, elements that appear to be nonprinting gridlines in your table frame may instead be cell borders that do print.

If you choose a table format, elements that appear to be nonprinting gridlines in your table frame may instead be cell borders that do print.

If you choose to show special characters in your publication (which I recommend), each cell also displays an end-of-story mark that looks like a small starburst. (You see these marks in text boxes too.) As with other special characters, end-of-story marks are displayed only on-screen; they aren’t printed.

If you choose to show special characters in your publication (which I recommend), each cell also displays an end-of-story mark that looks like a small starburst. (You see these marks in text boxes too.) As with other special characters, end-of-story marks are displayed only on-screen; they aren’t printed.

Moving around in tables

Publisher has only two navigation techniques specific to table frames:

Press Tab to move to the next cell (to the right). If there’s no cell to the right, the next cell is the first (leftmost) cell in the row immediately below. If you press Tab in a table frame’s lower-right cell, however, you create an extra row of cells at the bottom of the table frame.

Press Tab to move to the next cell (to the right). If there’s no cell to the right, the next cell is the first (leftmost) cell in the row immediately below. If you press Tab in a table frame’s lower-right cell, however, you create an extra row of cells at the bottom of the table frame.

Press Shift+Tab to move to the previous cell (to the left). If there’s no cell to the left, the previous cell is the last (rightmost) cell in the row immediately above. If you press Shift+Tab in a table frame’s upper-left cell, nothing happens.

Press Shift+Tab to move to the previous cell (to the left). If there’s no cell to the left, the previous cell is the last (rightmost) cell in the row immediately above. If you press Shift+Tab in a table frame’s upper-left cell, nothing happens.

If the cell you move to contains any text, these movement techniques also highlight that text.

Creating a table frame

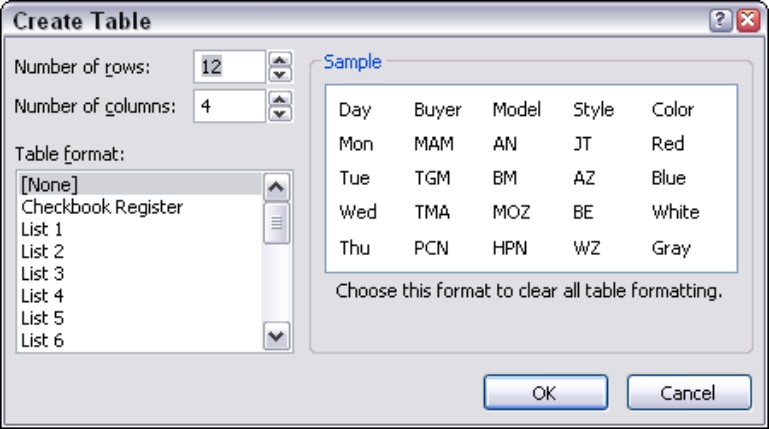

Chapter 5 briefly explains how to create a table frame: Click the Insert Table tool in the toolbox and then click and drag the frame outline. Table frames are different from text boxes in this respect: After you create a frame outline, you have to make a selection from the Create Table dialog box that then appears. (See Figure 6-12.)

You make three selections in this dialog box:

Number of rows

Number of rows

Number of columns

Number of columns

Table format

Table format

|

Figure 6-12: The Create Table dialog box. |

|

Publisher lets you create tables as large as 128 x 128 cells and offers 21 different table styles, or formats. As you select a format, the program shows you a sample of the format in the Sample area of the dialog box. The [None] format displays a plain, unformatted table frame. When you click OK in the Create Table dialog box, Publisher creates your table in the frame you drew. If the size of the frame you draw is too small to contain the number of columns and rows you chose, Publisher displays a message box asking whether you want to resize the table to hold the selected rows. Click Yes to have Publisher resize the table so that it’s larger; click No to reduce the number of rows and columns in your table.

Each table format has a minimum default cell size. If you select a larger number of cells than can be accommodated, Publisher displays a dialog box asking your permission to resize the frame. If you click No, you return to the Create Table dialog box, where you can then reduce the number of rows and columns in your table. If you click Yes, you create a table with the number of rows and columns you specified using the minimum cell dimensions.

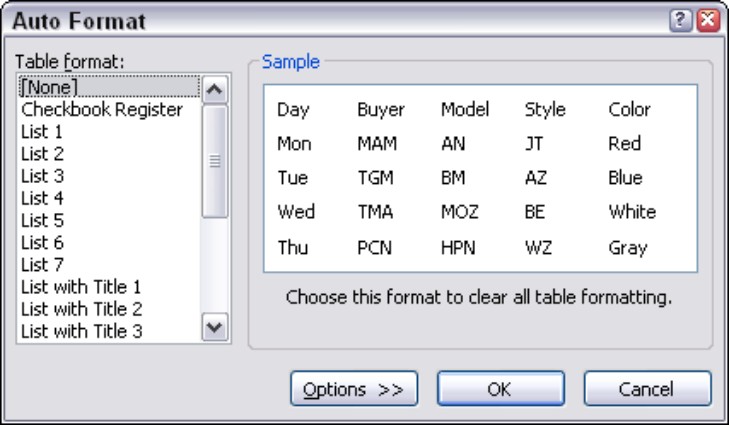

Modifying tables

When a table is selected, the Table menu commands become active. This menu, shown in Figure 6-13, contains commands you can use to modify the appearance of the table. If you choose the Table AutoFormat command, the Auto Format dialog box appears. (See Figure 6-14.) This dialog box is almost identical to the Create Table dialog box, shown earlier, in Figure 6-12. The differences are that you can’t change the number of rows or cells, but you can control some of the formatting options you apply to the table.

Although applying manual formatting is a good way to get your table frame to look just the way you want, it sometimes can mean plenty of work. Rather than manually format a table frame, use AutoFormat; it can do a lot of work for you. The AutoFormat feature not only applies character and paragraph formatting but also can merge cells and add cell borders and shading. Cell borders overlay table-frame gridlines and, unlike gridlines, are printed. Cell shading, a color or pattern that fills the interior of a cell, is also printed.

Click the Options button in the Auto Format dialog box to open a list of formatting options, such as Text Formatting, Text Alignment, Patterns and Shading, and Borders. You can select and deselect the options you want or don’t want to apply.

Resizing tables, columns, and rows

The structure of a table frame truly differentiates it from a text frame. Whereas a text frame is one big rectangle into which you dump your text, a table frame is divided into a grid of separate text compartments (cells). After you create a table frame, you’re not stuck with its original structure. You can resize the entire table frame; resize, insert, or delete selected columns and rows; merge multiple cells into one; and split a cell into separate cells. In short, you can restructure a table frame in just about any way you want.

|

Figure 6-13: The Table menu. |

|

|

Figure 6-14: The Auto Format dialog box. |

|

Here are some guidelines for resizing a table frame:

You can click and drag any of its selection handles. Publisher automatically adjusts the height of each row to fit each row’s contents.

You can click and drag any of its selection handles. Publisher automatically adjusts the height of each row to fit each row’s contents.

When you narrow or widen a table frame, thus decreasing or increasing the available horizontal area in each cell, Publisher often compensates by heightening or shortening some rows, thus heightening or shortening the overall frame.

When you narrow or widen a table frame, thus decreasing or increasing the available horizontal area in each cell, Publisher often compensates by heightening or shortening some rows, thus heightening or shortening the overall frame.

When you shorten a table frame, Publisher reduces each row to only the minimum length required to display the text in each row.

When you shorten a table frame, Publisher reduces each row to only the minimum length required to display the text in each row.

Regardless of whether your table frame contains text, you can’t reduce any cell to less than 1⁄8-inch square. You can heighten a table frame as much as you want, however; and Publisher heightens each row by the same proportion.

Regardless of whether your table frame contains text, you can’t reduce any cell to less than 1⁄8-inch square. You can heighten a table frame as much as you want, however; and Publisher heightens each row by the same proportion.

If you choose Table⇒Grow to Fit Text, the table’s row height expands to accommodate the text you enter.

If you choose Table⇒Grow to Fit Text, the table’s row height expands to accommodate the text you enter.

Here are some guidelines for resizing a column or row:

Move the mouse pointer to the edge of a column until it becomes a double-headed arrow. Then click and drag until the column or row is the size you want.

Move the mouse pointer to the edge of a column until it becomes a double-headed arrow. Then click and drag until the column or row is the size you want.

You can’t shorten a row to a shorter length than is required to display its text, and you can’t shrink any cell to less than 1⁄8 inch wide by 1⁄4 inch tall.

You can’t shorten a row to a shorter length than is required to display its text, and you can’t shrink any cell to less than 1⁄8 inch wide by 1⁄4 inch tall.

By default, when you resize a column or row, Publisher keeps all other columns and rows at their original size. Columns to the right are pushed to the right or pulled to the left, whereas rows below are pushed down or pulled up. The table frame increases or decreases in overall size to accommodate the change.

By default, when you resize a column or row, Publisher keeps all other columns and rows at their original size. Columns to the right are pushed to the right or pulled to the left, whereas rows below are pushed down or pulled up. The table frame increases or decreases in overall size to accommodate the change.

To keep a table frame the same size when resizing a column or row, hold down the Shift key as you resize. You then move only the border between the current column or row and the next one. If you enlarge a column or row, the next column or row shrinks by that same amount. If you instead shrink a column or row, the next column or row enlarges by that amount. In either case, all other columns and rows remain the same size, as does the overall table frame.

To keep a table frame the same size when resizing a column or row, hold down the Shift key as you resize. You then move only the border between the current column or row and the next one. If you enlarge a column or row, the next column or row shrinks by that same amount. If you instead shrink a column or row, the next column or row enlarges by that amount. In either case, all other columns and rows remain the same size, as does the overall table frame.

If you use the Shift key while resizing, you face even more limits. Unless you first lock the table frame (by selecting Table⇒Grow to Fit Text from the main menu), you can’t shorten the row below the row you’re resizing to less space than that lower row requires in order to display its text. And, you can’t shrink any adjacent column to less than 1⁄8 inch wide or a row to less than 1⁄4 inch tall. In addition, even if you lock the table frame, you can increase a column or row only by the amount you can take from the next column or row.

If you use the Shift key while resizing, you face even more limits. Unless you first lock the table frame (by selecting Table⇒Grow to Fit Text from the main menu), you can’t shorten the row below the row you’re resizing to less space than that lower row requires in order to display its text. And, you can’t shrink any adjacent column to less than 1⁄8 inch wide or a row to less than 1⁄4 inch tall. In addition, even if you lock the table frame, you can increase a column or row only by the amount you can take from the next column or row.

You can resize multiple columns or rows simultaneously. Just highlight those columns or rows, point to the right or bottom edge of the selection bar button that borders the right or bottom edge of your highlight, and then click and drag. Note that if you use the Shift key to resize, however, the program ignores your highlighting. You resize only the rightmost highlighted column or bottommost highlighted row.

You can resize multiple columns or rows simultaneously. Just highlight those columns or rows, point to the right or bottom edge of the selection bar button that borders the right or bottom edge of your highlight, and then click and drag. Note that if you use the Shift key to resize, however, the program ignores your highlighting. You resize only the rightmost highlighted column or bottommost highlighted row.

If you resize an entire table frame after resizing individual columns and rows, Publisher resizes the columns and rows proportionally. For example, if the first column is 2 inches wide and the second column is 1 inch wide, and you then double the width of the entire table frame, the first column increases to 4 inches wide, and the second column increases to 2 inches.

If you resize an entire table frame after resizing individual columns and rows, Publisher resizes the columns and rows proportionally. For example, if the first column is 2 inches wide and the second column is 1 inch wide, and you then double the width of the entire table frame, the first column increases to 4 inches wide, and the second column increases to 2 inches.

Inserting and deleting columns and rows

You can insert and delete as many as 128 columns and rows apiece. If you move to the last cell and press Tab, Publisher adds a new row at the bottom of the table frame and places the insertion point in the first cell of that row. You’re now ready to type in that cell. How convenient!

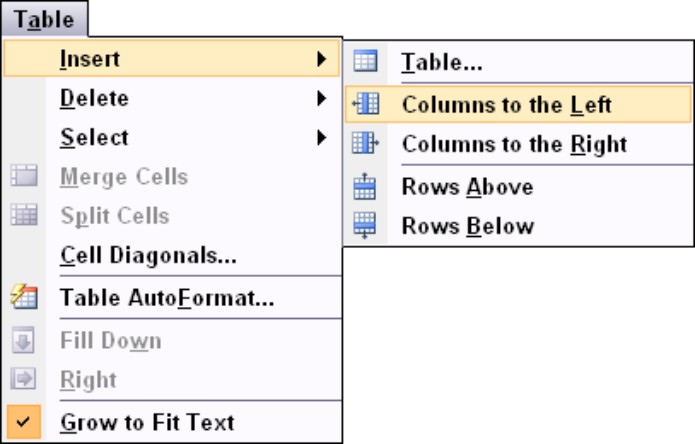

To insert rows elsewhere, or to insert columns anywhere, you need to do only a little more work:

1. Place the insertion point in the column or row adjacent to where you want to insert a new column or row.

2. Choose Table ⇒Insert.

Publisher displays the Insert menu, as shown in Figure 6-15.

|

Figure 6-15: The Table Insert submenu. |

|

3. Select whether you want columns to the left, columns to the right, rows above, or rows below.

Even if a table frame is locked (refer to the section “Resizing tables, columns, and rows,” earlier in this chapter), the program increases the table frame’s size to accommodate the new columns or rows.

Deleting a column is easy. Follow these steps:

1. Highlight the entire column you want to delete by placing the mouse pointer immediately above the column. When the pointer changes to a bold, downward-pointing arrow, click to select the column.

You can click and drag to select multiple columns.

2. Choose Table ⇒Delete ⇒Columns.

Deleting a row is just as easy:

1. Highlight the entire row you want to delete by placing the mouse pointer immediately to the left of the row. When the pointer changes to a bold, right-pointing arrow, click to select the row.

You can click and drag to select multiple rows.

2. Choose Table ⇒Delete ⇒Rows.

The quickest way to delete a single row or column is to put an insertion point in the row or column you want to delete, and select the option from the menu. The row or column is now deleted, and you didn’t have to highlight or drag over anything.

Merging and splitting cells

You may occasionally want to merge multiple cells so that they become one cell. For example, you may want to merge cells so that you can center a heading over multiple columns, as shown in Figure 6-16.

|

Figure 6-16: Cells merged to create column headings. |

|

Keep these concepts in mind when you’re merging cells:

To merge cells, highlight the cells you want to merge and then choose Table

⇒Merge Cells. Your highlighted cells become one. Any text in the individual cells moves into the single merged cell. You then can work with this merged cell as you would work with any other cell.

To merge cells, highlight the cells you want to merge and then choose Table

⇒Merge Cells. Your highlighted cells become one. Any text in the individual cells moves into the single merged cell. You then can work with this merged cell as you would work with any other cell.

After you merge a cell, you can split it into individual cells again. Click or highlight the merged cell and choose Table⇒Split Cells. The merged cell splits back into the original number of separate cells. The text, however, doesn’t return to the original, individual cells. Instead, all the text moves intact to the leftmost and topmost cell.

After you merge a cell, you can split it into individual cells again. Click or highlight the merged cell and choose Table⇒Split Cells. The merged cell splits back into the original number of separate cells. The text, however, doesn’t return to the original, individual cells. Instead, all the text moves intact to the leftmost and topmost cell.

In addition to being able to split cells horizontally, you can split cells diagonally in Publisher. Select the cells you want to split diagonally and choose Table⇒Cell Diagonals. In the Cell Diagonals dialog box, pick the type of diagonal you want (Divide Down or Divide Up) and click OK.

Working with table text

As with text boxes, you can fill a table frame by either typing the text directly into the frame or importing existing text from somewhere else. Except for the differences that I point out in the next two sections, the techniques for typing and importing text into text boxes and table frames are pretty darn similar.

Each cell in a table frame works much like a miniature text box. For example, when you reach the right edge of a cell, Publisher automatically word-wraps your text to a new line within that cell. If the text you type disappears beyond the right edge of the cell, you have probably locked the table. Choose Table⇒Grow to Fit Text to unlock it. If you want to end a short line within a cell, press Enter. The easiest method is usually to fill in the table frame row by row; when you finish one cell, just press Tab to move on to the next one.

There’s one important difference between typing in a cell and typing in a text box: When you run out of vertical room in a cell, Publisher automatically heightens that entire row of cells to accommodate additional lines of text. If you later remove or reduce the size of some of that text, Publisher automatically shortens that row. Compare this process to typing in a text box: When you run out of room, the text box remains the same size, and the program sticks the text into an overflow area or, if it’s available, a connected text box.

Importing table frame text

Just as you can do with text boxes, you can paste or insert a text file into a table frame. Some important differences exist, however. If your text is arranged in a table-like manner, such as in a spreadsheet or a word processing table, Publisher senses the arrangement and imports that text across the necessary number of cells in your table frame. If the text isn’t arranged in a table-like manner, Publisher imports all text into the current cell.

Although you may be able to use the Insert⇒Text File command to import text into a table frame (as described earlier in this chapter), the Windows Clipboard is much more reliable. Use it whenever possible.

Choose one of these two methods to paste or insert text into a table:

Cut or copy the text to the Windows Clipboard; then click the cell that will become the upper-left cell of the range and choose Edit⇒Paste or press Ctrl+V.

Cut or copy the text to the Windows Clipboard; then click the cell that will become the upper-left cell of the range and choose Edit⇒Paste or press Ctrl+V.

Select a table cell and choose Insert⇒Text File to import text into the table frame.

Select a table cell and choose Insert⇒Text File to import text into the table frame.

.jpg)

Here are some other important concepts to remember about bringing text into your table:

If the copied text is arranged in a table-like manner and the current table frame doesn’t have enough cells to accommodate all the copied cells, Publisher opens a dialog box to ask whether it should insert columns and rows as necessary. Click Yes to make sure that you paste all your text.

If the copied text is arranged in a table-like manner and the current table frame doesn’t have enough cells to accommodate all the copied cells, Publisher opens a dialog box to ask whether it should insert columns and rows as necessary. Click Yes to make sure that you paste all your text.

If you haven’t selected a table frame and the copied text is arranged in a table-like manner, the program creates a new table frame and places the copied text into that frame.

If you haven’t selected a table frame and the copied text is arranged in a table-like manner, the program creates a new table frame and places the copied text into that frame.

Although a table frame can look much like a spreadsheet, Publisher doesn’t have the power to calculate numbers. If you want to calculate the numbers in a table, calculate them in a spreadsheet program before importing. If you don’t have a spreadsheet program, pull out your calculator!

Although a table frame can look much like a spreadsheet, Publisher doesn’t have the power to calculate numbers. If you want to calculate the numbers in a table, calculate them in a spreadsheet program before importing. If you don’t have a spreadsheet program, pull out your calculator!

You can also make objects inline to table cells or to the text in a cell. When the object is inline to the text in the cell, the inline object moves with the text. When the object is inline to the table cell, the object is embedded in the cell and moves with the table. To make an object inline to a table cell or to text, right-click and drag the object. Release the mouse button where you want the object to land and then select Move Here or Move into Text Flow Here.

You can also make objects inline to table cells or to the text in a cell. When the object is inline to the text in the cell, the inline object moves with the text. When the object is inline to the table cell, the object is embedded in the cell and moves with the table. To make an object inline to a table cell or to text, right-click and drag the object. Release the mouse button where you want the object to land and then select Move Here or Move into Text Flow Here.

Editing table-frame text is much the same as editing text-box text. You need to know just a few extra procedures to efficiently highlight, move, and copy table-frame text.

You can use all the same mouse techniques to highlight (select) table-frame text as you use to highlight text-box text: drag, double-click, and Shift+click. You can also highlight table-frame text by combining the Shift key with any table-frame-movement techniques that I mention earlier in this section.

When you highlight any amount of text in more than one cell, you automatically highlight the entire contents of all those cells.

Here are some additional ways to select table-frame text:

Select the entire contents of the current cell: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Cell or press Ctrl+A (for All).

Select the entire contents of the current cell: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Cell or press Ctrl+A (for All).

Select every cell in a column: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Column.

Select every cell in a column: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Column.

Select every cell in a row: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Row.

Select every cell in a row: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Row.

Select multiple columns or rows: Click in any cell and drag across the rows or columns you want to select. Then choose Table⇒Select⇒Column or Table⇒Select⇒Row. Hold the Shift key and press the arrow keys to expand the selection.

Select multiple columns or rows: Click in any cell and drag across the rows or columns you want to select. Then choose Table⇒Select⇒Column or Table⇒Select⇒Row. Hold the Shift key and press the arrow keys to expand the selection.

Select every cell in a table frame: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Table.

Select every cell in a table frame: Choose Table⇒Select⇒Table.

Moving and copying table text

As with text boxes, you can use the Clipboard or drag-and-drop text editing (see Chapter 7) to copy and move text within and between table frames. If you like, you can even copy text between text and table frames.

Working in a table frame involves a very important difference, however: Whenever you move or copy the contents of multiple cells into other cells, Publisher automatically overwrites any text in those destination cells. To retain the contents of a destination cell, be sure to move or copy the contents of only one cell at a time. If you accidentally overwrite text when moving or copying, immediately choose Edit⇒Undo from the menu (or press Ctrl+Z).

Because of the way in which Publisher overwrites destination cells, rearranging entire columns and rows of text requires some extra steps. First, insert an extra column or row where you want to move the contents of an existing column or row. Then move the contents. Finally, delete the column or row you just emptied. Repeat these steps for every column and row you want to move.

Two commands on the Table menu, Fill Down and Fill Right, enable you to copy the entire contents of one cell into any number of adjacent cells either below or to the right.

Follow these steps to fill a series of cells in a row or column:

1. Select the cell containing the text you want to copy and the cells to which you want to copy the text.

To use the Fill commands, you must select cells adjacent to the cell containing the text to be copied.

2a. Choose Table ⇒Fill Down to copy the value in the topmost cell to the selected cells in the column below it.

or

2b. Choose Table ⇒Fill Right to copy the value in the leftmost cell to selected cells in the row to the right.

Formatting table text manually

You can format table-frame text manually to make that information easier to read and understand. You can use all the character- and paragraph-formatting options detailed in Chapter 7: fonts, text size, text effects, line spacing, alignment, tab stops, indents, and bulleted and numbered lists, for example. You can even hyphenate table-frame text.

The key difference when applying paragraph formatting in table frames is that Publisher treats each cell as a miniature text box. Thus, when you align text, the text aligns within just that cell rather than across the entire table frame. And, when you indent text, the text is indented according to that cell’s left and right edges.

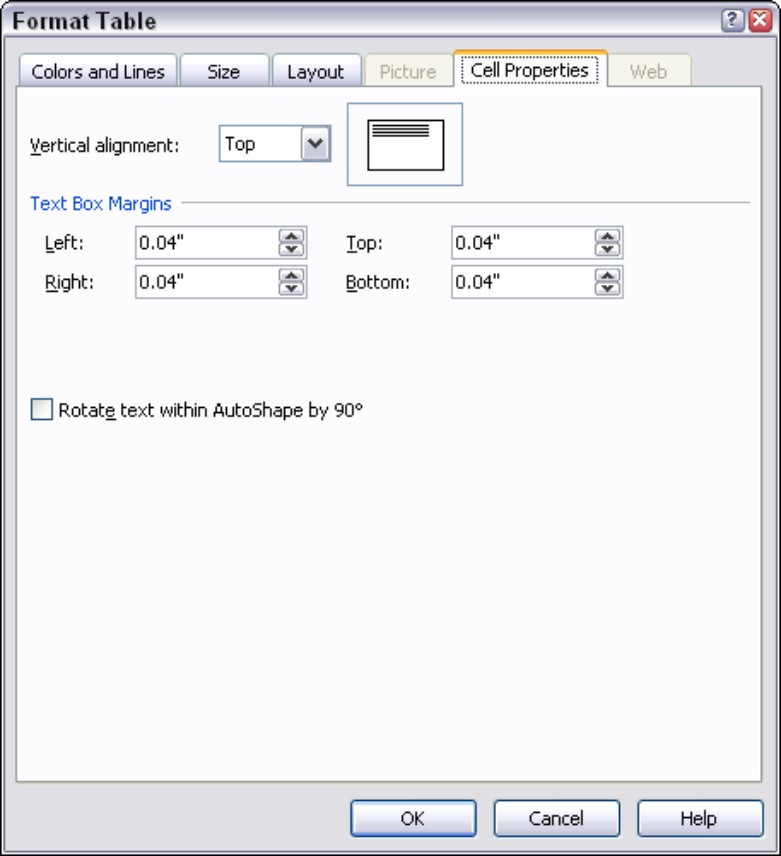

To improve the look of cells, you can also change cell margins, thus changing the amount of space between a cell’s contents and its edges. To change cell margins, choose Format⇒Table and click the Cell Properties tab. The resulting dialog box is shown in Figure 6-17.

|

Figure 6-17: The Cell Properties tab of the Format Table dialog box. |

|

Using Excel tables

Publisher lets you create and edit tables in your publication. It even has that cool Table AutoFormat command. However, if you’re a Microsoft Excel user, you may find entering and formatting your tabular data in Microsoft Excel more convenient. Maybe you already have a Microsoft Excel worksheet that contains data you want to include in your publication. You don’t have to waste time and risk data entry errors by retyping the information.

Importing an Excel worksheet

If you use Microsoft Excel and don’t want to remember all the instructions for working with tables in Publisher, don’t. Use Microsoft Excel to enter and format your tabular data and then import the worksheet into Publisher:

1. In Microsoft Excel, enter and format some tabular data.

2. Save the Microsoft Excel worksheet.

If you’re finished working in Microsoft Excel, you can close it.

3. Switch to the Publisher window by clicking its button on the Windows taskbar.

If the Windows taskbar isn’t visible, you can switch applications by pressing Alt+Tab. Hold down the Alt key and press Tab until the Microsoft Publisher 2007 icon is highlighted in the Cool Switch box that appears. Release both keys.

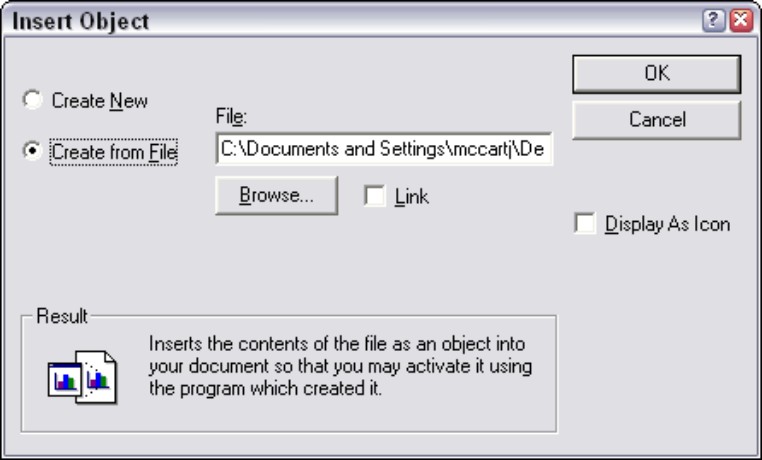

4. Choose Insert ⇒Object.

The Insert Object dialog box, shown in Figure 6-18, appears with the Create from File radio button selected.

5. Click the Create from File radio button and then click Browse.

The Browse dialog box appears.

|

Figure 6-18: The Insert Object dialog box. |

|

6. Navigate to (and select) the Microsoft Excel file you want to insert into your publication and then click Open.

You return to the Insert Object dialog box.

7. Click OK to insert the Microsoft Excel worksheet into your publication.

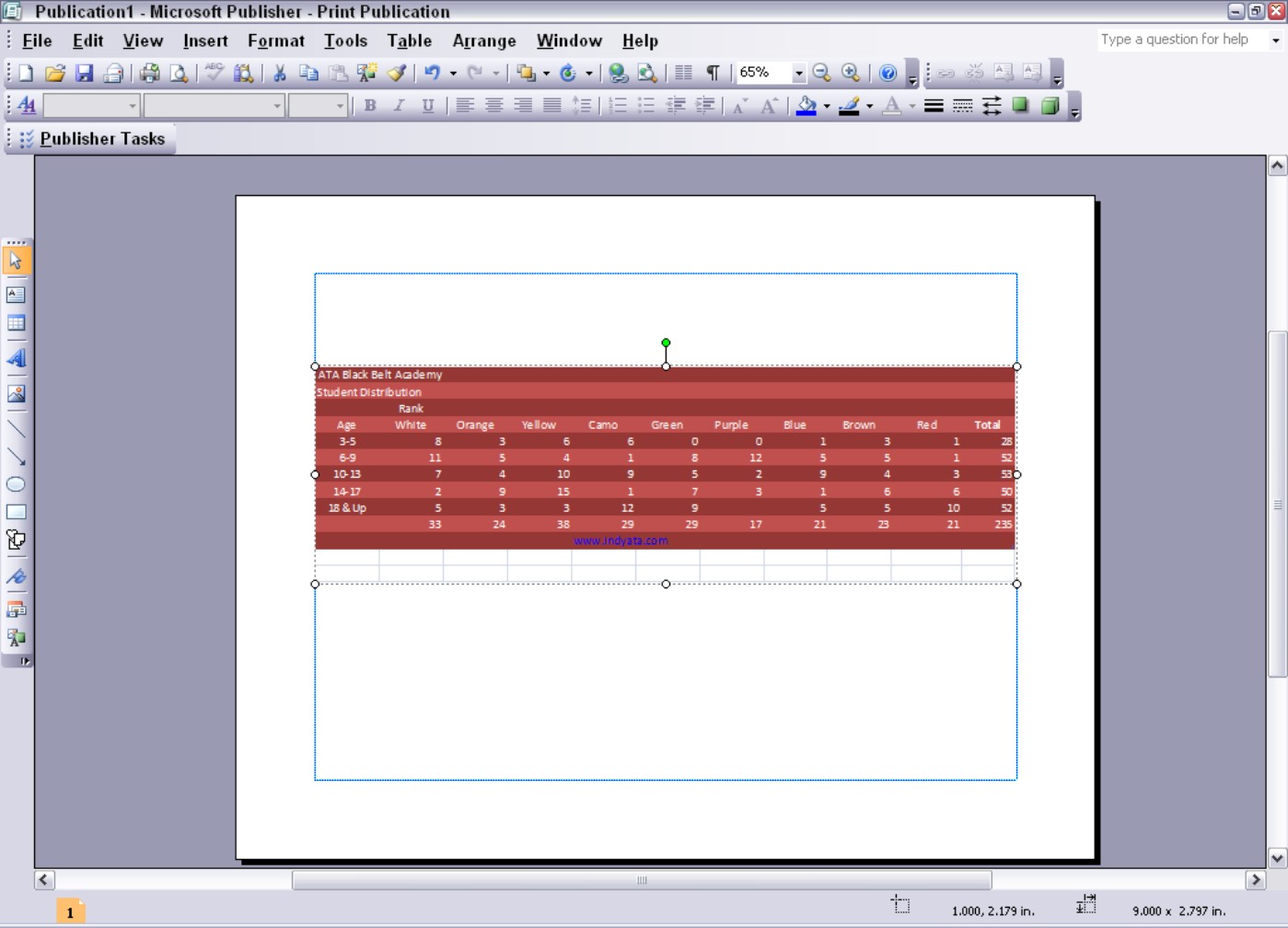

Figure 6-19 shows an example of an Excel worksheet inserted into a publication.

The Excel worksheet you insert into your publication isn’t really a table. I know: If it looks like a duck, waddles like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it must be a duck. Well, in Publisher, it isn’t a duck, er, table. It’s an object. If you select the newly inserted Excel worksheet and choose Table from the main menu, you notice that none of the Table commands is available.

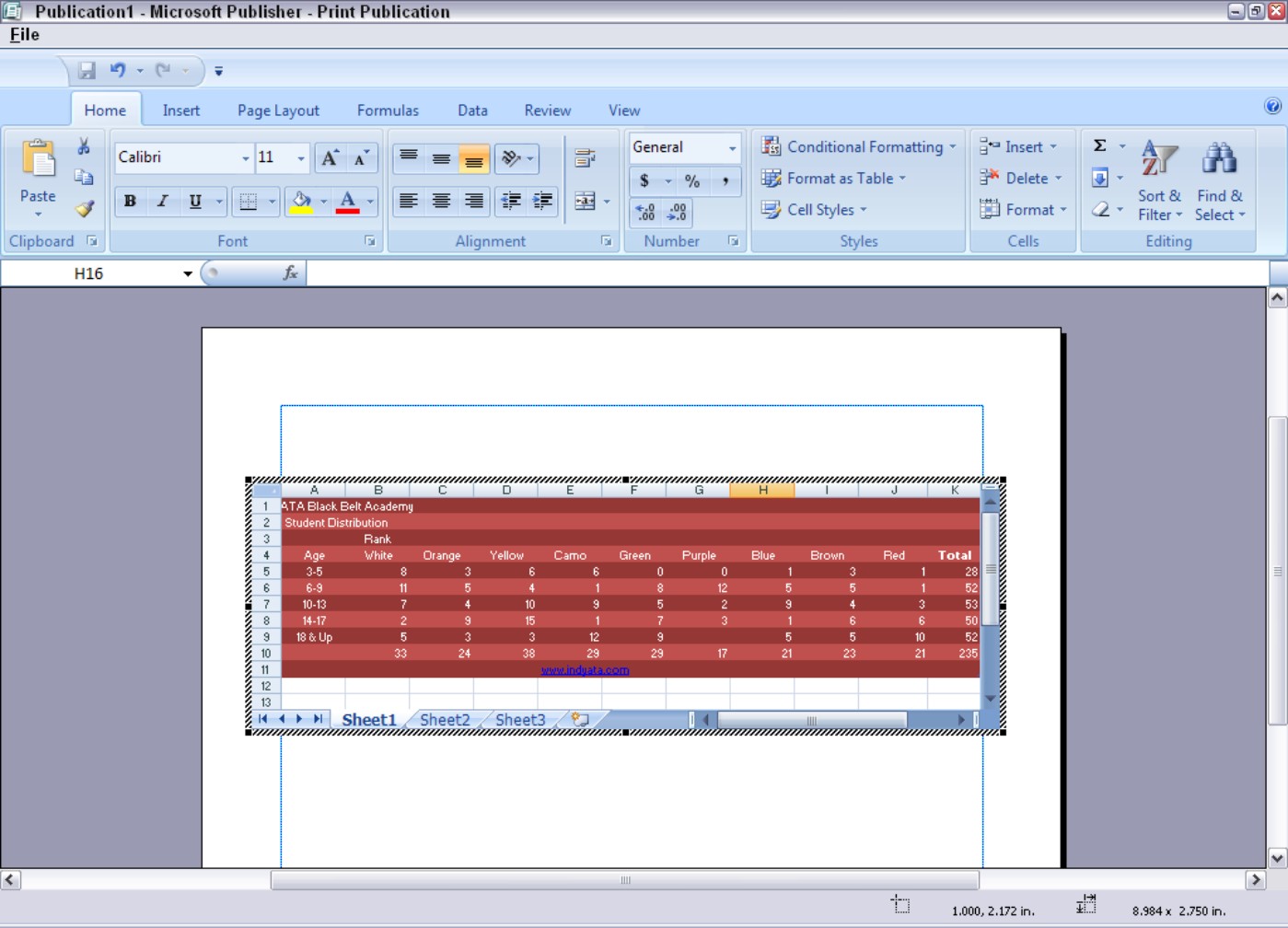

Editing an Excel worksheet in Publisher

So you create a jazzy-looking worksheet in Microsoft Excel, save it to your hard drive, and import it into Publisher. That’s great — until you realize that you spelled your company’s name incorrectly. Do you have to launch Microsoft Excel, open the worksheet, correct the spelling of the company name, save the worksheet, and import it into Publisher again? Yes.

|

Figure 6-19: An Excel worksheet object in Publisher. |

|

Okay, just kidding. You don’t have to do that. Just double-click the worksheet to launch Microsoft Excel inside Publisher. Although the title bar still proclaims that you’re in Publisher, the menu bar and toolbars change to those belonging to Microsoft Excel. (See Figure 6-20.) In fact, because I created the sample worksheet in Microsoft Excel 2007, when I edit the worksheet, the Publisher menus and toolbars are replaced by the fancy new Excel 2007 Ribbon! Edit the worksheet as you would edit in it Excel. When you finish making changes, just click anywhere outside the worksheet. That’s all there is to it!

Accessing tables in Access

If you’re a database diehard who’s wondering whether you can use your Microsoft Access tables in your publications, the answer is Yes. You can even use your Microsoft Access query results. Essentially, you have two options for getting data from your Access tables and query results into Publisher. You can import the entire table (or query results), or you can select part of the table (or query results) to bring into Publisher.

|

Figure 6-20: The Excel menu bar and toolbars show up inside Publisher. |

|

Follow these steps to import an entire table or query results:

1. In Microsoft Access, open the database that contains the table or query you want to use in your publication.

2. Click the Tables button in the Objects pane of the Database window.

To import the results from a query, click the Queries button in the Objects pane of the Database window.

3. Select a table or query and then click the Copy button on the Standard toolbar. If you’re using Access 2007, click the Copy button in the Clipboard section of the Home tab.

4. Switch to the Publisher window by clicking its button on the Windows taskbar.

If the Windows taskbar isn’t visible, you can switch applications by pressing Alt+Tab. Hold down the Alt key and press Tab until the Microsoft Publisher 2007 icon is highlighted in the Cool Switch box that appears. Release both keys.

5. In the Publisher window, choose Edit ⇒Paste, press Ctrl+V, or click the Paste button on the Standard toolbar.

Publisher creates a new table containing the records from your Microsoft Access table or query.

Publisher creates an honest-to-goodness table from your Access table or query. Format the table just as you would format any other Publisher table. After pasting the table into Publisher, resize the table to your liking.

If you want to use only a portion of the records in your Microsoft Access table or query, select the records before clicking the Copy button in Step 3 in the preceding step list.