“What was that about?” Zander asked once the dirigible had disappeared from sight. Pucci, sensing it was safe, flew down and landed on Zander’s shoulder.

“I don’t know, but I hate those damn agents,” M.K. said, picking up a small rock from the driveway and chucking it at one of the oak trees. It made a dull thud and a red squirrel jumped down from an upper branch and sat there for a minute looking dazed. “Run, run,” Pucci squawked at it, cackling. “Run for your life!” The squirrel ran around the side of the house.

I looked around nervously, though I knew no one could hear us. “The thing is,” I whispered, “I did see that man.”

“What?” M.K. wheeled around. “Who was he?”

“I thought you looked nervous,” Zander said. “What happened?”

I scanned the road again, completely paranoid now. “Inside. I wouldn’t put it past them to leave someone behind to spy on us.”

They followed me into the house and through the front hallway. The house hadn’t warmed up yet, and I shivered as we stepped into Dad’s study.

“He was an Explorer. He had a clockwork hand. I thought he was going to mug me,” I told them once we were inside. “But instead he gave me this and said it was from Dad.” I took the package out of the backpack, unwrapping it completely, and held it up for them to see. “The New Modern Age of Exploration by R. Delorme Mountmorris.”

“A book?” M.K. asked. It was cold without a fire in the fireplace, and she took a bearskin Dad had brought back from Grygia off one of the couches and wrapped it around her shoulders.

The room was filled with candlesticks and statues and carved masks and odd-looking animal skins and hides from Dad’s travels. There were a few photographs on the walls of places that Dad had visited. As an Explorer, he’d been allowed to use a camera on his expeditions, though the government had controlled how much film he got and which pictures could be developed. I looked up at the photograph of him at the summit of Mount Anamata, grinning and holding his arms out as though he were holding up the sky.

It was a strange-looking room, I suppose, with Dad’s collections and bits and pieces of gadgets and utilities scattered all around. I loved it, though, because it reminded me of him.

Even though I knew there was no way Francis Foley could hear us, I pressed a button on the wall and the government-issued radio squawked to life. “…restored peace in the Fazian capital,” a radio announcer was saying. “Government agents were able to secure the square before significant casualties occurred.”

“Hah!” M.K. said. “I wonder how many Fazians died before they ‘restored peace’?”

“Peace!” Pucci squawked. “Ha, ha! Restore Peace!”

The announcer went on. “President Hildreth announced an additional one thousand BNDL peacekeepers would be deployed to mountainous regions of Deloia in order to secure the Raproot mines in the territory of Deltan. Spokesperson…”

“They can’t hear us.” Zander reached up to shut off the radio. “Well, are you going to tell us?”

I told them about the man with the clockwork hand and put the book down on the special table in the center of the room. The table had clips for holding the big paper maps that Dad had used for his explorations and that he had made based on his travels. He’d been an expert cartographer, one of the best of the New Modern Age Explorers who had had to learn to make paper maps again after the Muller Machines were all shut down. He had made incredible maps of all of the new places discovered by the Explorers of the Realm. He’d also made maps for us, made-up maps of storybook places, and treasure maps that led us to chocolates or coins hidden in the woods behind our house. He’d made maps with disappearing ink and maps that were hidden inside other maps and once, for M.K.’s birthday, a secret map that you had to peel away from a dummy map on top and that led to her present, a new soldering iron.

The wall above the table had once been covered with frames holding his maps, their delicate blue and red and green and black lines forming amazing patterns. But Francis Foley and his agents had taken them all the night they’d come to tell us Dad had disappeared, and now the wall was scarred by the unfaded rectangles on the wallpaper where they’d once hung.

I lifted the heavy leather cover. Printed books had started to be made again after the Muller Machines were outlawed, but they were still pretty scarce and I had read the ones Dad had in his library over and over. I’d never seen this one.

“It’s about the New Modern Age of Exploration,” I told them, skimming the introduction. “Just the usual stuff about Arnoz and the Muller Machines and the Explorers of the Realm and BNDL.”

It was history that everyone knew, the first part about the Muller Computing Machines. They had kept track of numbers, stored information, and made maps of the world, of the countries of the Allied Nations, and the Indorustan Empire. They did other things too, connected you to networks of other machines and showed you pictures of faraway places. The idea for the machines had been brought to George Washington by a spy in 1791. The plans had been developed by a man named J. H. Muller, an engineer in the Hessian army who hadn’t been able to get the Hessians to build the machines. But in 1880, the Americans finally had. There had been a lot written about how, without the machines, America might not have won the war over Britain and then the rest of Europe. Without the military weapons controlled by the Muller Machines, the United States and its Allied Nations might not have been able to force the Indorustan Empire into a stalemate in 1970, bringing the long years of war between the two superpowers to a halt. The Muller Machines had become so much a part of everyone’s lives that people trusted them completely. Once the gasoline from Texas ran out, there wasn’t much to be had and only a very few people approved by the government could fly on airplanes or own cars. No one traveled or explored the world. Everyone believed the Muller Machines that there wasn’t anything left to explore.

You could take “vacations” on the Muller Machines, and see photographs of all kinds of amazing places, even feel the heat of the sun, or the chill of the snow, from the machines. Dad said that people would take time off from work, even put on their bathing suits or ski clothes in their living rooms, never realizing how ridiculous it was.

And then the machines were hacked. Over the course of three months, a series of coordinated attacks on the networks and the power stations that kept them running brought it all down and the “century of the Muller Machines” came to an end. No mail, no power, no trade. It had happened when Dad was eight, and for a couple of years there was no heat, no money, and very little food. Martial law was declared, but things were so bad that the government was overthrown the first winter, and when the new government came in, President Barbado outlawed the Muller Machines and anything that had been run by them, including the power stations. Engineers returned to what had worked in that distant past: steam and clockwork engines, old-fashioned to be sure, but safe as could be.

“Here’s the stuff about the New Lands,” I said, reading aloud.

“Little did the citizens of the world know that in the midst of a crisis of epic proportions, a light of hope and possibility was shining high on a cold and forbidding mountain.”

“The book says that?” M.K. asked. “That’s really corny.”

“No, that’s what I think. Of course that’s what the book says.” I crossed my eyes at her and went on.

R. Delorme Mountmorris detailed how one day, a couple of years after the failure of the Muller Machines, a young biologist and explorer named Harrison Arnoz, who had been living in a remote region of Eastern Europe near the Indorustan border, studying bear populations, discovered that where the “official” maps showed absolutely nothing, there was in fact an entire mountain range, new species of animals, and a group of tree-dwelling people who had never had contact with the outside world. Only a few months after Arnoz told the world about this new region, called Grygia, a commercial cargo ship got lost north of Denmark and came upon a small sea, obscured by a glacier, that appeared not to be on any of the official digital maps. The ship’s captain and crew had discovered the New North Polar Sea.

There was only one conclusion: the maps of the world were wrong.

Pretty soon the Explorers were heading out to discover what else had been hidden on the Muller Machine maps, and the discoveries from the New Lands started to trickle in: an ultra-strong metal in Grygia called Gryluminum that could be used to make fabric and armor; a breed of hearty, high-yield cattle in Deloia; disease-resistant bananas in Fazia. BNDL found itself in the position of governing the New Lands, and the American Newly Discovered Lands Corporation—or ANDLC—was started to run the mines and farms and factories and to send all the goods home. First President Barbado’s government and then President Hildreth’s had controlled everything very tightly, anxious to make sure that the United States and its allies owned all the new discoveries.

And that was when the Archaics—the “Archys”—had gotten going, making cars and airships and furnaces and dishwashers that were powered by steam and coal and clockwork gears, technologies that didn’t require gasoline or electricity. Dad was an Archy and I guess we were, too.

There were also the Neotechnologists—or “Neos”—who dreamed of wind power and solar batteries and dressed in their strange, bright, fabricated outfits—plastics and rubbers and odd fabrics, flashing lights embedded in their bodies. But the government suspected them of building secret Muller Machines and kept them from experimenting too much. Only a handful of Neo inventors had successfully developed new technologies, like gliders and electric autos. A lot of Archys refused to use these strange, silent machines, but Dad had always said that he didn’t care who had made his boat or plane, as long as it worked.

Mountmorris wrote all about it, about the new Explorers who went out to find the New Lands, about how they were celebrated for their discoveries, and about how, around the time M.K. was born, the new discoveries had trickled to a stop and the government had decided we’d found everything new there was to find.

The problem was that there wasn’t enough of anything to go around.

And so the people in the territories and colonies we’d claimed had started fighting back. And just as we started eyeing the territories claimed by the Indorustans, they started eyeing ours, too.

It was pretty likely that the uprisings in Simeria were just the beginning.

“We know all this,” M.K. said in an exasperated voice. “Why did Dad want us to see this?”

“I don’t know,” Zander said. “We don’t even know who this guy is.” He seemed annoyed, and I thought it might be because the Explorer had given the book to me and not to him. Zander always talked about how he was the one who was going to follow in Dad’s footsteps and go to the Academy for the Exploratory Sciences, how he was the one who was going to make a discovery and join the Expedition Society. I loved maps and understood them better than he did, but he didn’t care about that.

“The thing that I never got,” I said as I flipped through the pages of history, “is why it took so long for the New Lands to be discovered.”

“Because of the Muller Machines,” Zander said, still sounding annoyed. “They were wrong and people became so dependent on them that they didn’t question the maps. People just went to the places that were on the maps. They didn’t look for new places. The government didn’t let them.”

“But someone had to put the information into them, didn’t they? The coordinates and everything.” I had always wondered about this. Whenever I’d asked Dad, he’d just told me again about the Muller Machines and how the government hadn’t let anyone travel freely or use gasoline for anything but an approved purpose. I’d never found his answers satisfying.

“I don’t know, Kit,” Zander said. “See if there’s anything about Dad in there.”

I opened the book to the table of contents and sure enough, there was a chapter entitled “Alexander West: Mountains and Mapmaking.”

For the next half hour, we turned the pages of the book, reading about all of his famous expeditions and discoveries during the New Modern Age: his ascent of Mount Anamata, the tallest of the mountains in the New Lands; his discovery of St. Helena, a new volcanic island in the Caribbean; all of his scientific and mapping expeditions to the New Lands. I’d heard about all of it before, of course, but it was interesting reading someone else’s account of Dad’s bravery; he hadn’t been one for bragging about his expeditions and had always made it sound like he’d lucked into whatever record it was he’d set. There were chapters about other Explorers too: Leo Nackley, Jacob Omboodo, Delilah Neville, and all the names we’d come to know.

The book was full of photographs of Dad with his best friend, Raleigh McAdam. In all of them he was wearing his Krakoan alligator hat, which had been made for him during an expedition to Krakoa, and his Explorer’s vest, which he was never without. The vest had been as much a part of him as his right arm; it was made of patches of different hides: multi-colored Krakoan alligator, green Fazian anaconda, reddish-brown Juboodan whizrat, and other skins I couldn’t remember the names of. But Dad, who didn’t have most Archy Explorers’ aversion to synthetics, had also included patches of Gryluminum and plastics, the Gryluminum forming a sort of breastplate over his heart and vital organs. The vest was lined with the soft, incredibly warm fur of the blue Arctic namwee, a weasel-like creature discovered around the New North Polar Sea. The namwee’s fur had been discovered to be both extremely warm in cold climates and extremely cooling in warm ones.

And, of course, the vest was embedded with gadgets, its pockets filled with his expedition “utilities”—small brass gadget boxes the size of a pack of playing cards or a lighter that might transform into a knife or an inflatable sled at the touch of a button.

“Why,” Zander asked, leaning over my shoulder, “would anyone risk his life to give you that? It’s just a book.”

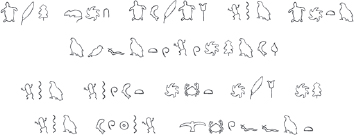

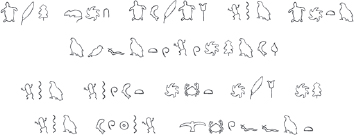

“I don’t know.” I really didn’t. It didn’t make any sense to me. I flipped through the book and was reading about Leo Nackley, who had gone to school with Dad and had gone on some expeditions with him, too, when I noticed some symbols scrawled in the margin of the page, in the bright red India ink that Dad had always used in his mapmaking.

“What are those?” M.K. asked, pointing to them.

“Beats me.” They looked like Native American symbols to me, little birds and feathers and animals and suns and moons and trees. Dad had loved doodling when he was reading or writing, so it didn’t seem strange that they were there. But there was something about the way they were arranged that made me look more closely.

They appeared to be random, but that was what seemed strange to me. If they were doodles, wouldn’t Dad have arranged them in some sort of pattern? A bird, a feather, a frog, a turtle, a bird, a feather, a frog, a turtle? I hesitated. Maybe I was overthinking this. But when I looked again, I saw what was really bothering me. The symbols were grouped together like… well, like… words.

“What are you doing?” M.K. asked.

Ignoring her, I found an old magnifying glass on the mantel and used it to study the symbols in the thin, late-spring light coming through the library window. The glass wasn’t bad: I could see the little turns Dad’s pen had taken, where he’d made a false start or gone back to correct something. He’d been very careful, separating the symbols so it was clear where one word ended and another began. And suddenly I understood.

It was a code.