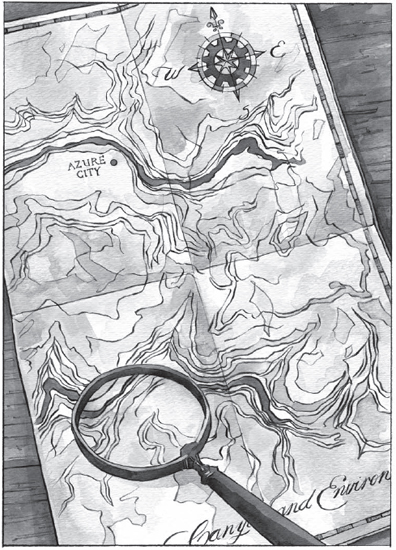

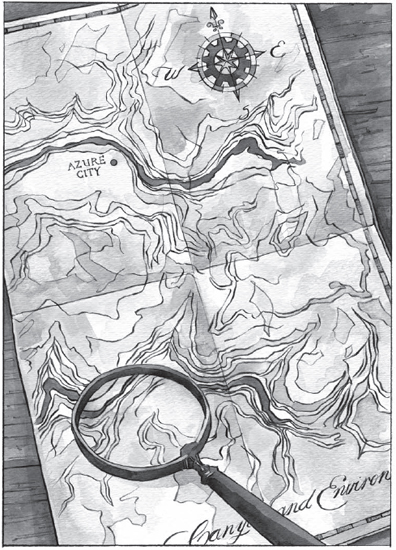

To be precise, it was half a map. It had been neatly torn in half so that it ended abruptly on the left-hand side. The title, written in red ink at the bottom in Dad’s handwriting, was cut off so that it read “ed Man’s Canyon and Environs.”

“Is it one of his?” M.K. asked in a quiet voice.

“I think so,” Zander said. “I think that’s his handwriting.”

“Of course it’s his handwriting,” I told them. Even if I hadn’t recognized the handwriting I would have known that Dad had made the map. It was beautifully done, the graceful, wavelike contour lines describing the depth of the canyons and mesas, the words written in his distinctive, scrolling handwriting. The map was obviously of a desert region, probably in the American Southwest. I made note of a town called Azure City and crossed the room to search for it in the big atlas on the windowsill; I found it not far from the Grand Canyon. So it was northern Arizona. The legend was missing; it must have been on the other side.

I took the map over to the window to look at it in the bright spring sunlight coming in the library windows. I looked through the magnifying glass and the tiny lines seemed nearer.

“We’re missing part of it,” I told Zander and M.K.

Pucci had been dozing up on the curtain rod, but now he flew down and perched on the windowsill, looking at the map and bobbing his head. “Canyon,” he squawked. “Azure Canyon.” We all looked at him. It was weird; I could never tell if Pucci was just repeating something he’d heard or actually talking. Zander said that black knight parrots had been known to put sentences together using words they knew, but he wasn’t sure, either.

“He’s right,” I said. It was hard to tell without the rest of it, but the map seemed to focus on Azure Canyon. I knew that this part of Arizona was full of deep, winding canyons, carved out of the bedrock by rivers over thousands and thousands of years. Some of them were now dry or wet for only part of the year, and others—like the Grand Canyon—had rivers running through them still. By reading Dad’s carefully drawn contour lines, I could tell that Azure Canyon was quite deep, dropping at least half a mile down into the earth—the thin lines crowded together to show the sheer drop of the canyon’s walls. Like all of Dad’s maps, this one was easy to read and beautiful. From the arrangement of the contour lines, it seemed like maybe another canyon branched off from Azure Canyon, but it must have been on the other half of the map.

I looked up at my brother and sister, who seemed as confused as I was. “But why was it hidden in the desk?” M.K. asked.

“And why did he cut it in half?” Zander ran his finger along the rough edge.

“How did he get the book to the man with the clockwork hand?” I asked the silent room.

None of us had any answers.

“Obviously he wanted us to find the map,” I said. “But it was only by chance that he got it to me. What if I hadn’t cut through the alley? What if someone else had been there?”

“That’s a good point,” Zander said. He thought for a moment. “You said he looked like he was just back from an expedition. Maybe he was… I don’t know, traveling with Dad or something, and he brought the book back for us.”

“Everyone who was traveling with Dad in Fazia died,” M.K. said. “At least that’s what they told us.” We were all quiet, remembering the night Francis Foley had arrived, telling us that pieces of Dad’s party’s boats had been found in the Fazian River, in an area “unsuitable for human survival.” We’d known exactly what that meant. If the Fazian crocodiles or piranhas hadn’t gotten him, the cannibals had.

“Yeah, that’s what they told us. But I’ve gone over and over the maps and there’s no way they were in Bartoa when the government says they were. I told you that I don’t believe it for a minute.”

They both looked at me. “So what, you think Dad’s alive?” Zander asked.

“No. If he was alive he would have let us know. But I don’t think he died where the agents say he did.”

“Because I think that…,” Zander started, then trailed off, looking troubled. “Forget it.”

We all fell into silence for a minute, remembering all the times Dad had complained about the government agents. He was always talking about how they asked so many questions about his expeditions and how he thought that they sometimes followed him, how no Explorer could go anywhere without BNDL’s okay. Dad hadn’t been a big fan of the government.

“What do you think it means, anyway?” M.K. whispered, as though they were listening in at this very moment. “Do you think Dad wants us to go to this canyon, wherever it is? Do you think he went there?”

“I have no idea,” I told her. “I don’t remember him ever talking about going to Arizona. He didn’t go on any expeditions there or anything like that. Arizona was explored a long time ago. By the Spanish. He liked to go to the New Lands.”

“I think he wants us to go to Arizona,” Zander said. “I think that’s what he’s trying to tell us.”

“Hold on a minute.” It was just like Zander to start packing before we knew anything about the map. “What we need to do first is find out whether he ever went to Arizona and whether there’s another half to the map.”

“Who’s this Mountmorris guy?” M.K. asked, picking up the book. “He seems to know a lot about him. Was he friends with Dad?”

I went over to the bookshelf and took down Dad’s raggedy copy of The Explorer’s Yearbook, which the BNDL agents hadn’t found interesting enough to take with them. “Here he is.” I read aloud from his entry, “‘Randolph Delorme Mountmorris. Author, historian, and collector. Notable for his books about the New Modern Age of Exploration and for his collections of animal specimens and artifacts from the New Lands.’ That’s pretty much it. There’s an address here too. In the city. On Fifth Avenue.”

“He must have met Dad when he was writing the book,” Zander said. “Maybe he could tell us about the map.”

“I think we have to be careful…,” I was starting to say when I heard the faint chug of an engine. “Did you guys hear something?”

Pucci cocked his head, listening, too.

We were all silent for a moment, and I was just about to say that I must have imagined it when we heard knocking from the hallway.

“Knock, knock,” Pucci cackled. “Knock, knock.” He hid himself behind the dingy curtains.

M.K. went to the window. “SteamCycles,” she told us, standing behind the drapes so she couldn’t be seen. “With BNDL logos on their sides. They’re back!”