Lulled by the motion of the train and curled up on piles of hay, we slept through the darkness in an empty cargo car on the Philadelphia—Los Angeles line.

It wasn’t until daylight angled through the half-open door that we really looked at the leggings and Explorer’s vests. We examined them as we sped across the country.

“Look,” M.K. said, “there’s a tool set on mine.” She showed us a little flap on the front of her vest that concealed a complete miniature tool set. “And Dad put a bunch of utilities in these pockets. This one has a picture of a sleeping person on it. Wonder what that does.” She laid three more brass boxes out on the floor of the car and poked and prodded them. “I can’t figure out what they do, though.”

There were a lot of buttons and flaps on M.K.’s vest, and she pressed them one after the other, trying them out. “Hey, what’s this?”

“Ow!” Zander grabbed his right shoulder and we all looked up to see a small arrow embedded in the wall of the cargo car. “You shot me!”

“It just nicked you,” M.K. said, inspecting a tiny wound on his upper arm. “Don’t be such a baby.”

I checked my own vest. Aside from the shining brass compass embedded in the animal hide on the front, there was also a small pocket on the inside that contained a sextant, just like the little tool Dad had used for navigation. I opened another inside pocket and found a brass spyglass. “Look at this,” I told them. “It has ten degrees of magnification, like a really powerful set of binoculars!”

“What do you think this is?” Zander asked us, holding up a small brass utility about the size of a pack of playing cards that he’d found in one of his pockets. He pushed a button on the box and a flame shot out of one end. A little fire started in the hay and he jumped on it to stamp it out. “That might come in handy,” he said. He held up another one, this one a bit larger, and when he pressed a button, a large piece of silver fabric, complete with zippers, shot out. “It’s a sleeping bag!” Zander said, delighted. “Thin but warm. And I think we each have a light on the vests. He thought of everything.” He reached over and pushed a button on the left shoulder of my vest. A light shone out into the train car, illuminating a large area in front of me.

Zander also found a small hunting kit, containing a few arrows and a foldable bow, and we all found utilities in our pockets that we couldn’t quite figure out. We put some of them in the pockets on the leggings and left the rest in the vests.

“We’ll be all right now,” M.K. said, settling back against a pile of boxes at one end of the car. “He knew we’d need the vests.”

We were all quiet, thinking about Dad, wondering if this was what he had imagined when he’d hidden the gear in Raleigh’s closet. It was one of those moments when I missed him so much that I could feel the pain of it deep in my skin, like a hidden burn that wouldn’t ever go away. And somehow, Raleigh’s mention of our mother had seared a twin burn next to it. All the years of her absence, the way Dad’s eyes would cloud over when we asked him about her, it had all lodged there in my body and I felt something I’d let myself feel only a handful of times since he’d disappeared: pure, hot anger at him for leaving us.

I looked around at the graffiti-covered walls of the cargo car; symbols and pictures that I knew had been left by rail riders who had used the empty cargo cars to move around the country. Soon after the invention of the ultra fast trains, Neo kids who didn’t have anywhere to live had started riding the empty cars, defending their turf with the long-handled knives they carried.

The train moved quickly across Pennsylvania and down through Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas, and then straight across the wide fields of Oklahoma. Outside the cargo car, the sun rose slowly and we could feel the air get hotter and more humid as we raced west across the country. We took off our sweaters and opened the door of the car a bit, but there wasn’t much of a breeze and it wasn’t long before we were drenched in sweat. Even Pucci looked miserable, his feathers bedraggled and limp. The cookies Raleigh had given us were gone by the time we crossed the Oklahoma border. I had visions of us starving to death and dying of thirst in the hot train as the train chugged on for hours and hours.

We were speeding through a huge expanse of cornfields when all of a sudden, as the train slowed down around a bend, the door flew open and a Neo boy with spiky blue hair came crashing into the car.

He hit the floor hard and when he looked up and saw Pucci, he grinned and said, “Hey, where am I, the zoo car?”

“Funny,” Pucci squawked. “Very funny!”

He sat up and we all stared. He wasn’t too much older than we were. He was a thin, wiry boy who looked five inches taller than he really was because of the blue spike of hair that stood up like the blade of a circular saw. He had a pile of chains around his neck and little flashing lights embedded in his ears and neck. When he grinned at us, we could see that the insides of his lips were pierced with the lights, too.

“Whew. Hot in here. You got anything to drink?” Something about the way he said it put me on my guard.

“No,” I said. “Wish we did.”

“Ah. You’re thirsty, too? I’ve come down from the North myself. Didn’t know it would be so hot.” He studied us for a moment, his brown eyes wary. “You don’t look like the usual rail riders,” he said. “Not at all. You’re Archys, aren’t you? Where you ridin’ from?”

“Canada,” Zander said.

“That right? Huh.” He watched Zander for much too long, as though he was trying to see the lie on his face.

“Yeah,” Zander said, but not very convincingly.

The guy nodded at M.K. “She looks a little young to be ridin’ rails.”

“Looks can be deceiving,” said M.K, putting a hand on the sheathed knife on her belt. The guy looked surprised for a minute and then he smiled and said, “So they can, so they can.”

The train slowed and then stopped, and we were all quiet as we listened to the sleek sound of the doors whooshing open and the voices of passengers getting on and off. A few minutes later we were moving again. The rail rider was sitting with his back against the wall of the car, still watching us. The little lights in his ears and lips flashed in time, as though they were sending out some sort of message.

He laughed quietly. “So you don’t have a thing to drink, do you? That’s what you’re telling me?” He stood up. He was very tall, six-feet or more. “What about money, then? You got any money, four-eyes?” Self-consciously, I pushed my glasses up on my nose. “Riders share with each other. That’s the tradition.”

There was a long silence as we all looked at him, and then M.K. jumped up, the little knife out of its sheath and up in the air where the guy could see it. He sat back down again, laughed nervously, and held his hands up where we could see them.

“Hey, hey, sorry about that. Gotta try, you know, gotta try. But you three are all right. You’re all right. Yeah, yeah…”

M.K. stood there for another couple minutes, just to be sure he got the message, and then smiled sweetly at him, put her knife away, and sat down again.

He was quiet for a few minutes and then said, “Look, like I said, you three are all right. So I’m gonna tell you something. I’d get off this train if I were you. Word on the rails is that the next station up ahead is crawling with cops looking for three kids traveling with a black parrot. Modified, I heard. If I’m not mistaken, that’s you. Something about assaulting federal agents. I’m pretty impressed, I’ve got to tell you. Wouldn’t have thought you had it in you.”

I was already on my feet. “How much farther to the station? What are we going to do?”

Blue Hair put a hand out. “Easy now. You can make it. We’ll slow down up here on the final approach. The grass is pretty high there on the side of the tracks. I think you can jump out as we slow down and hide pretty well next to the rails. Crouch down until the train is gone and then you might want to lay low awhile. That’s my advice, anyway.”

“Thanks,” Zander said, standing, too, and holding on to the side of the rocking train.

“Hey,” Blue Hair said, “good luck and don’t forget this.” He pressed Raleigh’s newspaper into M.K.’s hand. “You’re probably going to want some reading material. Now go.” He slid the door open for us. Outside the car, we could see the cornfields flashing by.

And we could feel the train slow as it leaned into the curve.

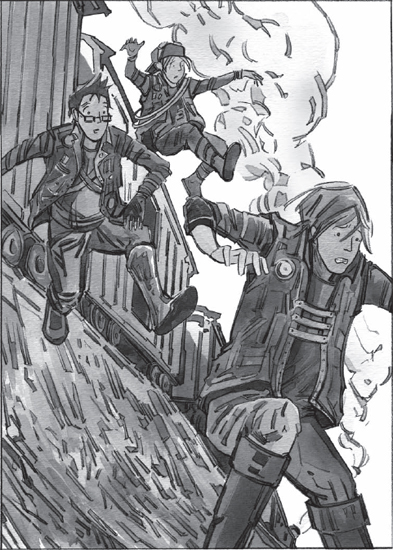

We jumped.