We descended as quickly as we could into Azure Canyon, the horses picking their way along the path, which zig-zagged down the steep canyon walls. The gray clouds overhead were gathering faster, but it was so hot that it seemed hard to believe it could ever rain.

My horse was a gentle palomino and she responded to my hands on the reins better than any machine ever could. After a while I relaxed into the Western saddle, letting her carry me along. I checked Dad’s map and the one that Bongo had given us every once in a while so I would know when to look out for Drowned Man’s Canyon. It was beautiful down there; the red limestone walls of the canyon were marbled with brown and gold and darker red and there were bright green cottonwood trees along the way. Every once in a while, a clear stream formed little waterfalls before it disappeared into the ground. The water tasted delicious, cold, and sweet. All along the walls were caves and crevices in the rock and it all made the canyon seem otherwordly, like some kind of desert paradise. I remembered reading about the ancient peoples of these canyons, who had built their houses high in caves in the cliffs in order to defend themselves from attackers.

“Yahoo!” I called out. “We’re free! There aren’t any pictures of President Hildreth to salute down here!”

“Yeehaw!” Zander called back.

“Yodeleheeho!” Sukey answered.

Pucci squawked, then mimicked Sukey’s yodel.

M.K. laughed and yelled, “Whoo whoo! It’s beautiful down here!” We gave the horses free rein and galloped along the path into the canyon.

Before long, we’d reached the canyon floor and we set off toward the West, into the thin sun. I took the compass out of my vest pocket to get our bearings, and once I’d established that we were heading west, just as the map indicated, I noticed a tiny counter in one corner of the compass. As the horses walked along, the numbers slowly went up. After I’d consulted the map, I realized it was tracking our mileage.

“Dad put a sort of odometer on it,” I told them. “It’s counting out the mileage as we go, like a pedometer for horses. I can compare this to the scale on the map and I’ll be able to figure out exactly where we are.”

“As long as we’re heading for Drowned Man’s Canyon, that’s all I care about,” Zander said.

“What do you think about those?” I asked Zander as we rode, pointing to the gray mass in the distance. The ugly bank of clouds we’d run into in the glider seemed to be settled to the North. “Anything we should worry about?”

“Maybe,” he said. “They’re pretty far away. And they don’t seem to be doing anything.” Pucci was flying up ahead of us, making big lazy circles in the sky, as though he was enjoying stretching his wings.

We rode as fast as we could, conscious of the Nackleys and Foley and his agents somewhere behind us. I didn’t know how they’d get out here, airship, maybe, or train, but I knew they’d be here soon.

I gave my horse a gentle kick in the side and trotted a little bit ahead of everyone, then fell back into step next to Sukey and her tall red mare. “So where do you live, anyway?” I asked her.

“That’s right,” said Zander, catching up to us and falling in on the other side of Sukey in a way that annoyed me a little. “We don’t know anything about you.”

“Oh, it’s not very exciting,” Sukey said. “Delilah and I live in the city and during the school year I go to the Academy.”

“How do you like it?”

Her whole face lit up. “It’s so great. This was only my first year, but the classes are amazing. This past year, I took the Science of Flight, Celestial Navigation, Introduction to Outdoor Survival, and Carnivorous Amphibians of the Southern Hemisphere. Next year I get to take Flight Strategy in Remote Jungle Regions and I forget what else. I can’t wait.”

“I heard you have to take Cartography and Compass Mapping,” I said.

“Is it true you learn how to fix engines and construct gliders?” M.K. asked.

The three of us listened in envy as Sukey went on about her teachers and fellow students. We had gone to the local elementary school for a while, but Dad hadn’t thought we were learning anything but government propaganda, so he’d been teaching us at home for the last couple of years.

“Lazlo Nackley goes to the Academy, too,” Sukey said. “He thinks he’s so much better than everyone. On the Final Exam Expedition last fall, he put tacks in a friend of mine’s hiking boots so he wouldn’t make the top of the peak we were aiming for. And once in our geography seminar, he and I got into an argument about the Grygian War. He said that the U.S. and the Allied Nations deserved the land because we had found it and the Grygians were too stupid to hang onto it. He said the Treason Camps were the Grygians’ own fault because they didn’t give in when we tried to take their land. I called him a dirty land grabber and he said he was proud of the name!”

“I think I remember Dad telling us about the Final Exam Expedition,” Zander said. “That’s where you have to plan a whole expedition all by yourself, right?”

“That’s right. And then the teachers pick the ten best plans and the kids whose plans don’t get picked get assigned to the other expeditions, and we go on them during the spring semester. How you perform on the expedition makes up 50 percent of your grade for the year.”

We rode on, stopping for a quick look at the famous blue waterfalls. They were pretty amazing; a bright turquoise color that didn’t seem like it could be natural. But the sun was going down and we knew we didn’t have much time. We had the lights on our vests and we decided that we’d keep going into the night, to stay ahead of BNDL and the Nackleys.

I’d been tracking the mileage, and Dad’s map showed the entrance to Drowned Man’s Canyon at eight miles along the floor of Azure Canyon, but when we’d been traveling for only five miles, we saw a narrow opening in the rock and a canyon that seemed to jut off in the right direction.

“That’s strange.” I checked the map again. “Dad’s map says it shouldn’t be for another three miles.”

Zander kicked his horse and trotted over to the entrance. “But this looks like it, right?”

I fumbled with the map that Bongo had given me. “Yeah, I guess. This map has it at five miles.”

“So Dad’s must be wrong,” Zander said.

“But Dad was never wrong. You guys wait here. I have to make sure that it isn’t up ahead.”

“But that’ll be six miles,” Zander protested. “We can’t waste that much time. This must be it, right? What else could it be?”

“We have to find out,” I told them, “just in case it’s the wrong one. Then we’d really be in trouble.”

“All right,” Zander said, looking exasperated. “I’ll go. I’m a faster rider.”

“I’ll go,” I said. But he’d already given his horse the heel of his boot and pulled up next to me, taking my spyglass out of my hands. He was off in a cloud of red dust before I could even put the map away.

“Let him,” M.K. said. “He is fast.”

“Three miles!” I called after him. “Check in three more miles!”

The three of us waited silently, watching as the sun sank and the walls of the canyon turned the colors of the sunset: red and pink and rippling orange. Zander was back twenty minutes later, racing along the floor of the canyon.

“I was right,” he said, giving me an ‘I told you so’ look that made me want to punch him. “Nothing up there. The canyon just gets narrower and keeps going. This must be it.”

“Fine.” I pulled my horse around and made my way into Drowned Man’s Canyon.

The opening was pretty narrow—just wide enough for the four of us to pass on horseback side by side—and water wouldn’t have drained out of it very quickly. I could see how Dan Foley had gotten into trouble. Once it started to rain, it would have been like being stuck in a giant bathtub.

As the horses trudged along the canyon floor, we saw that we’d entered a completely different landscape. For one thing, it was narrower, the walls steeper and made of a darker limestone, pocked with sinister-looking caves and crevices. Maybe it was the darkening skies and the fact that it was getting late in the day, but suddenly I thought about Bongo and his story about the ghost.

“Do you feel like we’re being watched?” M.K. asked.

I nodded, looking nervously over my shoulder. Pucci had come to sit on Zander’s saddle, as though something was making him nervous, too.

Twenty minutes later, the clouds were darkening, moving fast across the sky. When I felt a couple of drops on my face, I called out to the others, “What should we do?”

“Keep going,” Zander said.

It was raining harder and in a few minutes the rain started to fill up the canyon. The horses went more carefully, plodding along in the swirling water.

We kept pressing on along the canyon floor. Pucci had flown ahead a bit and now he circled back, calling out a warning. Sukey found a rain poncho in her pack. But the three of us were getting soaked. “Hey!” M.K. called out suddenly, and we turned around to find her sitting there, completely sheltered by an umbrella that seemed to have sprung out of her back. “Try your vests!” she shouted over the rain. She gestured toward the back waist of the vest and Zander and I both felt around on our own. I pushed the button that appeared under my fingers and, sure enough, I heard a whoosh and, two seconds later, was shielded from the rain by a large umbrella. Another two seconds and Zander was sheltered, too.

Sukey looked surprised, and a little jealous. I motioned for her to ride next to me, but she waved her hand to say she didn’t care if she got wet.

The horses were soaked now and they started moving nervously in the water, turning their heads and snorting in protest. Pucci, still on Zander’s saddle, was wet and bedraggled, his shoulders hunched against the rain.

“We’ve got to get up higher,” Zander called back to us. “It’s going to be a flash flood in a minute.” He pointed toward a steeply climbing bridle path that wound up the sides of the canyon. “Kit and Sukey, you go first.” The walls were almost completely vertical. I kicked my horse hard in the side and Sukey did the same to hers and we led them up the steep slope ahead of Zander and M.K. I was leaning so far back in my saddle that I was afraid I was going to fall, and every time I looked over the edge, I saw the swirling water and the steep slide down to the bottom.

It kept raining as we climbed, and down below us, in the canyon, the stream of water had turned to a river. If we had stayed down in the riverbed, the water would now be up to our chests. It was just as I’d thought: there was nowhere for the water to go and it was rising fast.

I peered through the torrential rain beyond my umbrella. A couple yards ahead, I could see a shelflike cave in the rock. It looked to be seven or eight feet high and I waved wildly at the others, pointing them toward it. Sukey and I pulled in and dismounted and Zander and M.K. did the same. Once we’d figured out how to return the umbrellas to our vests, we squeezed under the overhang and looked out at the veil of water cascading outside our shelter. The horses seemed unfazed now that we’d found higher ground, putting their heads down as the water ran off their backs and waiting for it to end.

Pucci found his way inside and he sat on the ground, squawking at us as if to ask what we were doing in such a terrible place.

“What is this?” M.K. asked, looking around. “Hey, it goes back farther. Look, it’s really big!” She felt along the back of the cave and disappeared into the darkness at the back.

“M.K.?” I called out after a couple of minutes. We didn’t hear anything and I was starting to worry when she popped her head out. “It’s huge,” she said. “And look at this.” She pointed toward the back, where I noticed, for the first time, the sound of falling water. When I ducked my head, I could see that there was a wide hole carved through the rock. There was a hole underneath that seemed to be draining water away from the cave. When I pointed my vest light at it, I could see chisel marks on the inside.

“It’s a chimney!” I told them. “Someone lived here and made that hole in the rock for a chimney.”

“What do you mean someone lived here?” Sukey asked, looking nervous all of a sudden. Outside, the rain was pelting the rock and we heard a clap of thunder.

“Long ago, maybe,” I told her. “There were lots of cliff dwellings in this part of the Southwest. I remember reading something about the geology. The rock is soft and the caves and tunnels formed easily.”

We sat at the mouth of the cave and looked out at the downpour. “When are we going to be able to get going again?” M.K. asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s bad out there. We’re going to have to spend the night here and get going in the morning.”

“If the Nackleys are on IronSteeds, the rain won’t slow them down.” Sukey looked worried.

“Well, we might as well make a fire and have something to eat.” Zander stood up and started looking for dry firewood that had been blown into the cave.

Pretty soon there was a nice pile of firewood and some pine branches to use as kindling, and Zander was hunting around in our vests for matches.

“I would think there would be some,” he said.

“I’ve got some,” Sukey said, but when she got them out of her pack, she found that they were soaked. I tried to strike one against the box, and then on the wall of the cave, but the match just hissed a bit and didn’t light.

“All right,” Zander said, picking two sticks—one large and flat and one thin and small—out of the pile of firewood. “We’re going to have to do this the hard way.” He took out his pocketknife and started whittling away at the smaller one, and in a couple of minutes he had a long, needle-shaped stick. With his knife, he made the other stick into a flat plane, then carved a little hole in it and inserted the smaller stick’s point into the hole.

“There’s an old saying: Know how to make a fire with two sticks?” he asked us as he started to twirl the needle-shaped stick between his hands.

“How?” Sukey asked.

“It’s easy as long as one of them is a match,” Zander answered and we all laughed.

He kept twirling the stick quickly between his palms, but nothing happened. M.K. went over and started rummaging around in our vests, taking out all of Dad’s brass utility boxes.

“Hang on,” Zander said. “I’ve almost got it.” He kept twirling when suddenly there was a whoosh and the little pile of wood erupted in flames. Pucci squawked and retreated to the mouth of the cave, and when we looked up, we saw M.K. standing there holding Zander’s flamethrower utility.

“Wish Dad had given this to me,” she said. Twenty minutes later, a large fire was crackling in the cave. Pucci kept his distance. Zander had noticed he was afraid of fire, and we thought maybe it was from dropping bombs or whatever awful things they’d made him do in the territories.

We buried two cans of beans in the coals to heat them, making a meal of them and some beef jerky we’d found at the little market in Azure City. It wasn’t much, but we were so hungry we ate every last bean.

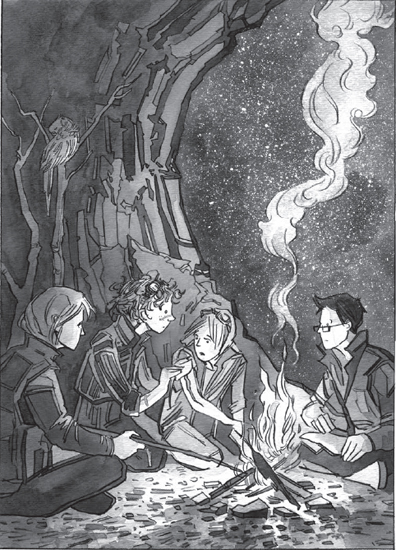

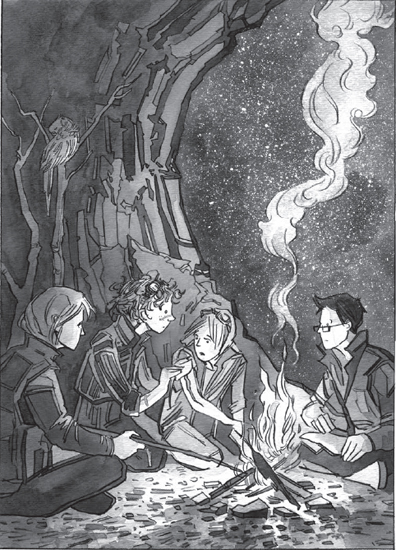

We all sat around the fire drying our clothes, watching the smoke curl upwards through the chimney, looking up at the stars outside the cave. Pucci dozed on a stick away from the fire, making little murmuring coos in his sleep. The sky was an inky blue-black, the stars brighter than I’d ever seen them. The air even smelled different out here, wet and piney from the rainstorm, now filled with the sweet, woody scent of our fire.

“Clear the square,” Pucci murmured in his sleep. “Big fire.”

Sukey raised her eyebrows. “Did he just say ‘Clear the square’?”

“Yup,” M.K. said. “He says that a lot in his sleep.”

“You know that’s weird, right?”

“Zander thinks he has flashbacks,” I told her. “About things he had to do when he was working in the territories. Dropping bombs and stuff.”

“Okay… Where did you get him, anyway?” she asked.

“There was a stray cat that used to hang around our house, to catch mice,” M.K. told her, “and one day, Zander looked out the window and saw it playing with something. When he went out, he found Pucci, almost dead. Zander saved him. A couple of weeks later, when he was strong again, he picked up a rock with his legs and dropped it on the cat’s head. That cat never came back.”

“Have you been by yourselves since your dad died?” Sukey asked us. She hesitated. “You never said anything about your mother. Delilah’s friends said they never met her.”

Zander and M.K. were silent so I said, “She died when M.K. was a baby.”

“I’m sorry.” Sukey poked at the fire with a stick. We all stared at the tiny orange-hot sparks that popped and shimmered between the burning logs.

Something about the darkness, the silence, made me say, “Dad never talked about her. He refused to. So we stopped asking. But when we were at Raleigh’s, he told us she was called ‘Nika’ and that she was really smart, that she knew all about the Muller Machines and how they worked. Dad never told us that. Not once.”

Sukey hesitated again. “How did she die?”

“SteamCar accident,” Zander said.

“What about her family?”

“We never met her parents, if that’s what you mean.” I stared at the fire. “They died before Zander was born.”

“When Dad disappeared, we kept expecting them to make us go to an orphanage or something, but they never did,” M.K. said. She reached up to rub her arm and I realized I’d forgotten about her cut.

“They had agents watching us, though,” I told Sukey. “I’d see them every once in a while. They must have known about the map. They took all of the maps in the house and when they didn’t find it there, they must have figured that the guy with the clockwork hand would try to get it to us. We think that’s why they didn’t send us to an orphanage. They wanted to use us as bait.” I’d been thinking about it some more. “And they must have had someone watching me by the markets. They didn’t see me talking to the man with the clockwork hand, but he was spotted.”

“So this map is pretty important,” Sukey said, “if they’d go to all that trouble.”

“I guess it must be.”

“M.K.,” Zander said, “how does your arm feel?” She’d been rubbing it the whole time I’d been talking. “Let me see it.”

She leaned down toward the fire and pulled her sleeve up so we could see the gash. I felt a little wave of fear wash over me. It looked swollen and angry red, the edges of the cut pulling away.

“That’s nasty,” Sukey said. She refused the juper berry cream I took out of my vest, getting a real first-aid kit out of her backpack and dressing M.K.’s wound. “Here, this should take care of the infection, M.K. But you have to tell us if it starts hurting again.” M.K., already looking happier, agreed, and Sukey put the juper berry cream and the first-aid kit back in her pack.

I got out the map and laid it out carefully by the fire so I could study the route and check it once again for any sign of where the old mine might be. We would be hiking farther into the canyon tomorrow and we still had no idea where to look. With the Nackleys behind us, we didn’t have much time.

As I studied Dad’s map, I was bothered again by the fact that the entrance to Drowned Man’s Canyon hadn’t been where it was supposed to be. According to Dad’s scale, it should have been eight miles along the floor of Azure Canyon. But we had entered it at five miles. What had happened to those additional three miles? Time and rivers could make canyons wider and longer, but nothing could have altered where the canyon started.

“What are you doing?” M.K. asked, coming to sit beside me.

“I don’t know. There’s something funny about this map.” I showed her how I’d compared it with the tourist map that Bongo had given us and my own calculations as we’d ridden through the canyon, and found that Dad’s map was wrong.

“But he was never wrong,” I muttered, as much to myself as to M.K. I fooled around with the two halves of the map, making sure I’d matched them up precisely. They fit perfectly when I placed the two halves together so that they didn’t overlap at all, but I started experimenting, overlapping the edges and trying to match up the contour lines representing the depth of Drowned Man’s Canyon on one side with the lines on the other side.

Dad’s map represented Drowned Man’s Canyon as a series of closely spaced squiggling contour lines, each one representing points connected at the same elevation.

Contour lines were only invented in the sixteen hundreds, when a French mapmaker came up with them as a way of representing the actual features of a landscape, the mountains and valleys and lakes and rivers. Until then, maps had been able to represent places in only one dimension. You could draw a blue circle for a lake, but you couldn’t see how deep the lake was or how steeply the edges of it dropped off toward the middle. You could draw mountains and hills, but on paper Mount Everest would appear to be the same height as a little foothill. But once topographical maps—that is, maps that represented the rising and falling of the landscape—came along, you could read a map on paper or on a Muller Machine and get a feel for the landscape, for whether it was flat or hilly or wet or dry. It was funny, sitting in the cave high in the walls of Drowned Man’s Canyon, looking at a map representing those walls.

I shifted the sides of the map.

“Wait a second,” I said. Zander and Sukey looked up from their conversation.

“What?” M.K. watched as I fiddled with the edges of the two halves, overlapping them and then making a few calculations. Instead of matching up at the edges, the right side of the map—the side we’d found in Dad’s desk—was now laid over the other half—the half we’d found in the Map Room—covering about three inches of the left side. The contour lines still matched, but the strange lines that I had assumed were mesas and hills to the north of Drowned Man’s had now come together.

“The map wasn’t wrong,” I said. “I was.”

“What do you mean? And what’s that?” M.K. pointed to the squiggly contour lines. Zander and Sukey had come over and were looking at the map over my shoulder.

“We haven’t been thinking about why there are two maps or, I mean, two halves,” I told them, so excited by my discovery that I was talking too fast. “Dad wanted us to find the map, right? He wanted us to find both halves of it. But why split it in half? Look.” I placed the maps next to each other. “Here’s Dad’s map of Drowned Man’s Canyon and here’s the one Bongo gave us.”

I went on. “Remember when I said that we reached the turnoff to Drowned Man’s Canyon too soon? Well, we did, according to Dad’s map, anyway. Because Dad’s map is wrong.”

“But you said Dad was never wrong,” M.K. said suspiciously.

“Well, he wasn’t. Or at least, he was wrong on purpose. Because the two halves of the map aren’t meant to be matched up perfectly. It’s meant to go like this.”

I pointed to the two halves, now overlapping by three inches rather than matching up exactly. I waited, for dramatic effect. “It goes like this instead.”

Now we were all looking at the same canyons we’d seen before, but Azure Canyon was a bit shorter than it had been and branching off from Drowned Man’s Canyon was another canyon. I was too excited to stop and calculate the depth but I assumed it was about the same as Azure and Drowned Man’s.

“When you do it like this,” I told them, so excited now I could barely contain myself, “there’s another canyon there. See?” I pointed to the spot where it broke off. “There is a secret canyon. He found it and included it in his map. He split the map in two so that we could put it together only if we actually came here! He knew that I would map it as we came through the canyon. He knew that I would notice that it wasn’t right. It must be where the treasure is. And we’re the only ones with this map. We’re the only ones who know there’s a secret canyon and the only ones who know how to get there.”