14

Separation

There was a war coming, war in Iraq. As the killing around us went on, we escaped again. Jericho was a frequent choice: apart from visits to Val’s house with the Mount of Temptation looking down on us, and ruins of crusader sugar mills and the walls of Jericho below, there was Sami Musallam’s riding stables out toward Allenby Bridge, offering horses instead of trail nags, and Hisham’s Palace with its famed tree of life mosaic and its star window. On one visit there the children and I met a young Palestinian archaeologist restoring the mosaics. He let us in even though the site was closed, and showed us around, explaining everything. The mountains of Jordan in the distance loomed blue exactly as in the David Roberts lithographs; the children ate tiny apple bananas we had bought in the central square and ran about the ruins in the glow of the late afternoon light, swiping at the green grass pushing through the stones, poppies, buttercups, and blue flowers too, and laughing at the jangling goat bells of the nearby grazing herds. And yet Jericho was also a sad, bewildered place, like so much of the West Bank, its population virtually imprisoned for months on end, its produce also, and therefore minimal incomes for everyone, with not much to do. It was semicircled by a two-meter trench dug by the IDF.

In the heat of the Middle Eastern summer, a couple of months after Operation Defensive Shield, the French consul general and his Cuban wife sent out a general invitation to expats, knowing that we were the only ones allowed through the checkpoints, to stay at a Jericho hotel with a pool and tennis courts. One guest, a consul general from Latin America, headed off like the rest of us, glad of the break and to be away from Jerusalem, but she and her husband, who was Palestinian, had to make a choice: should he ride in the car with his wife and risk being picked on by the checkpoint soldiers, or should he try to sneak into Jericho using the tracks through the desert, being made to feel like a criminal? I saw him later, at the party. I did not ask which option they had taken.

Andrew and I sped down the Jerusalem–Jericho road, the children and Julita in the back, the car thermometer registering the rising temperature as the signs on the blistered rocks outside registered our sinking below sea level. Along the plain to the lone checkpoint that holds in the Jerichites, the temperature was 114°F and the few cars in line weren’t moving. In the distance, inside the ring of defenses, an out-of-place high-rise block stood like a giant molar against the soft dunes: the Jericho casino where Israelis had gambled happily before the Intifada, now empty and idle.

We waited twenty minutes, the heat sweeping in dry eddies around us. I got out of the car, in a hot summer dress that stuck to me and stab heels that were soon gritty with dust, and walked across the no-man’s expanse toward the overheated soldier who motioned me to stop. It was the heat that dictated, not the soldiers. I walked on up to him and asked “What’s going on? Why is no one being allowed through?” Boiled with sweat in his heavy fatigues, he reeled off the reasons: “It’s our job, it’s the rules, we have to do this.” But he looked as unconvinced as I was.

I said, “Surely you could let some through?”

“Yeah,” he agreed, wiping the lines of sweat with the back of his thumb as they tracked down into his eyebrows, “but at least we let the pedestrians through first because of the heat.”

I looked around at the empty plain, the city hazy in the distance. The Jericho checkpoint was a long, long way outside the city. They were only pedestrians because the IDF wouldn’t allow their cars through. By this time it was clear that I was neither a suicide bomber nor a Palestinian, so he said we could pass. “You should have come straight to the front,” he said. “What about the others?” He shrugged. I wanted out of the heat, I had the right ID. There was nothing I could do.

We apologized to the other drivers sitting in their hot cars, knowing they would have to wait, perhaps for hours. They smiled back. “What can we do?” they shrugged. Sumud again. We slipped through the chicane. And the soldiers were not awful. What they have to do is awful.

Later, by the tepid pool, Xan appeared dripping with blood, his chin split. A Palestinian pool attendant, Khaled, had rescued him and wouldn’t let go even though I explained I was his mother, and a doctor, and that I could decide if he needed stitches. He needed stitches. Khaled showed me the way through the quiet sunlit streets to Jericho’s hospital, telling me about his career as an engineer. “Not many engineering jobs in Jericho these days,” he said.

The hospital was out toward the checkpoint, set away from the desert road in a pool of sand and heat. A gift from a European government, it was new and crisp, but nearly empty. The corridors were slow, with linoleum and a small quiet crowd of people huddled at one end. Again the special treatment—we were guests. The red-headed Palestinian doctor left what he was doing and waved us into a yellow and gray trimmed dock. A couple of juniors watched the doctor, world-weary and dour, as he swung my boy on to the table and peered at his bleeding chin.

Xan all stitched up, I bought him an army hat from a startled stall owner in town—they were used to isolation—and we returned to the pool. It was, Khaled told me, the hottest day recorded since 1947. We sweated out our weekend, dancing in the dark moonlight, children fast asleep.

Back in Jerusalem, as the summer wore off we stuck to the Forest of Peace, with a walk in the first midday cool of the season, and a picnic on the lawn by the former Shabbat café. This had been a small place run by two young Israelis, Josh and his friend, who prepared minted lemonade and huge bowls of pasta for all-comers, Jewish, Palestinian, whatever, and open on Saturdays, hence the name. Then it burned down, mysteriously, leaving a charred shell on the edge of the lawn.

A Canadian journalist lived just above the café on the promenade. Her children were at the lycée with ours, and our boys often played together. One day she called to arrange their next encounter, and suddenly interrupted herself: “This Wall,” she said, “is wicked. And guess what, it’s Israelis who are saying so.”

She had just returned from an assignment: “In the North there’s a kibbutz on one side of the 1967 border and a Palestinian village on the other, inside the West Bank. They’ve had peaceful relations for years.” When some of the Palestinian youths started running stolen cars through the kibbutz, the kibbutzniks built a fence along the ‘67 line, but this caused no ill feeling. In fact the kibbutzniks were proud of their example: “Coexistence is possible; it really works,” they told her.

“But now,” she said, “a wall must go up to separate the terrorists—all Palestinians are terrorists—from Israel.” Okay, the kibbutzniks said, that’s one way to deal with a problem, to fence the two sides apart—they had used this method themselves. “But the wall is not going along the ‘67 border, it must go three kilometers inside. It just happens to separate the Palestinian villagers from their fields, their olive groves, their livelihoods.” And those trees and crops the villagers were not separated from were uprooted to make way for the wall itself. She used the word “wall.” Later we learned to say “Barrier.”

“You know, it’s not Western journalists who are complaining about the placement of the wall,” she said again, “it’s the kibbutzniks. And they’re not just complaining, they’re mad.” By depriving the Palestinians of their incomes, they told her, their own government was turning their neighbors into terrorists— “What else can they be now?” the kibbutzniks asked.

She had seen olive trees being pulled up to make way for the Barrier: “There are ‘relocated’ olive trees all over Israel,” she said, referring to the practice of uprooting trees from the West Bank for replanting elsewhere. “You see the despair on the farmers’ faces, and you don’t have to imagine the hopelessness.” The women and children were scrabbling among the remnants of their groves, wary of the bulldozers, trying to pick up as many olives—the last of their fruit—from the dust as they could. “The Israeli government officials,” she said, “tell the kibbutzniks that they don’t understand the political and security implications.”

It was the first eyewitness story I heard about the Barrier. There had been talk for months, but so many other things had happened that it had been lost in the background, especially with the prospect of a war in Iraq. A year before Operation Defensive Shield there had been reports that Likud had a plan, proposed by legislator Michael Eitan, to erect high fences around Palestinian enclaves of self-rule. “We are not talking about ghettos, people will be able to enter and exit through a security gate,” said one of his aides.1

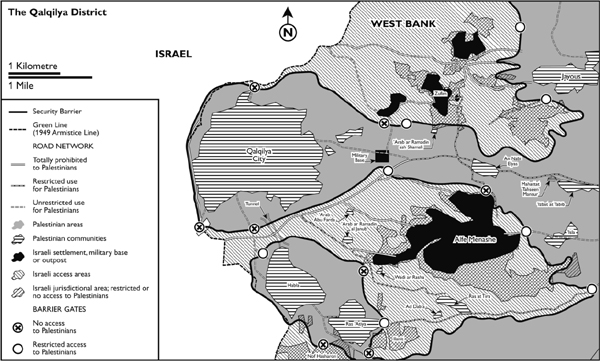

The Security Barrier, or security fence, apartheid wall, terror fence—there were many names—grew out of a Labor plan for unilateral separation (in other words a separation without negotiation with the other side). Fostered by Israeli fears and the longing to prevent civilians from being killed by suicide bombs while trying to lead a normal life, the idea gained acceptance. In June 2002, after a spate of bombings that left scores of Israelis dead and injured, Likud accepted that it had not protected Israelis, and adopted Labor’s plan to build a barrier, one between Israel and the Occupied Territories. It was to be, as far as possible, impenetrable to terrorists. Teams of specialists were recruited to design and build the structure, a combination of patrol roads, barbed wire, trenches, tracking zones, electronically sensitized wire fencing, and stretches of an 24-foot-high wall of concrete. It would be manned at intervals by soldiers in watchtowers, and monitored via the electronic paraphernalia. The Barrier would help ensure Israelis the “right to life.” It would run along the Green Line.

If the last sentence had turned out to be true, the Barrier that Israel built would certainly have had the support of most of the international community, most Palestinians, and a great many Israelis. Instead, the Barrier brought a storm of bitter disagreement and a hearing at the International Court of Justice. Some Israeli commentators were in no doubt that the political and security implications, which the kibbutzniks had been told they did not understand, were straightforward. In their view the Barrier may have started as a security measure, but it became a tool for taking land.*

I saw the wall soon enough, on my first trip to Qalqilya, a small Palestinian town about 45 miles north of Jerusalem on the Green Line between Israel and the West Bank, to visit the hospital’s obstetric department. My coworker Laura and I drove behind an UNRWA truck, partly to help us find the way, but also because we thought we might stand a better chance of getting into the town if we were with a supply truck.

It is not far from Jerusalem to Qalqilya but the journey time, as always, was dictated not by distance but by the closures. The cluttering of checkpoints along the direct route through the West Bank ruled out going that way. We followed the UNRWA truck as it went west into Israel toward Tel Aviv, then turned north. The road across the toes of the foothills was being superseded by a new motorway coursing north–south: Route 6, the vertebral column of Israel that would open up the interior to development. The old road, which had itself been the new road not so long ago, was spliced by roadworks for the new motorway. And every now and again there were ruins, remnants of unburied Palestinian villages along the way.

Once on the opened motorway, we found ourselves suddenly parallel with the wall. Here the Barrier can be called a wall because it is a wall. The vast concrete slabs towered over us, dwarfing even the giant construction vehicles still at work on it, smoothing out the skirts of the wall. The skirts were swathes of cleared land, wiped clean of crops, sheds, houses, and humans in order to protect the wall. In some ways, the wall was like other sound barriers along motorways except that its height was so massive, so un-human. And at intervals there were watchtowers.

We began a dance, twisting back and forth. We knew that Qalqilya was on the other side of the wall, but we couldn’t find a way in. The lead truck turned across the motorway and doubled back. The driver carried on for a while, then paused to make a call. He climbed down from the cab, raised his arms in a shrug at us, then asked directions of a work crew on the roadside. He listened, climbed back, started up and headed west, away from Qalqilya—then doubled back eastward.

I looked for signposts. There were plenty, but none said “Qalqilya.” The map showed it as a big town, a splash of gray on white paper. It existed on paper, but the real town was hidden. We kept driving, wondering. Into the West Bank the road scaled down and became ragged. A checkpoint straddled the road. Settler cars streamed through to their jobs in Israel; all other vehicles waited. More road, and at last Qalqilya appeared, to our left beyond a gash of stripped land. We made a left turn, doubling back again, on to the one remaining road into Qalqilya.

The long arms of the wall had mutated into fence, and the wrists of the fence were tied together at a final checkpoint. This was the pore through which Qalqilya breathed. The IDF watched, controlled. In the line ahead of us sat a line of vehicles, trying to get in. A Frenchwoman left her NGO-marked car in the line and came over to talk to us. She had been there two hours already. “Medical work—they won’t let us through. One of the soldiers is insisting.” Aid organizations bringing supplies and help to the Occupied Territories were accustomed to being blocked and hassled, “and we’re the ones doing the Israelis’ job for them—keeping the occupied going,” she said angrily. Just then the UNRWA truck, laden with food and medicine, was called forward out of the queue, and allowed through the checkpoint. We made a bid for his slipstream, and eased through. The NGO worker was still trying to get in when we came back out again, hours later.

The UNRWA hospital we were visiting was tucked away inside the town. The truck slipped into an improbably small alley, forced an oncoming car to reverse, almost scraping the buildings on either side as he went, and squeezed right, disappearing into a compound. We followed the truck, parked, and were greeted by the staff of the obstetric department. They showed us around the cramped wards and explained that a new wing was under construction. In the maternity ward grandmothers and fathers came up to us, handing out chocolates wrapped in stiff paper, celebrating their new babies’ arrivals. Siblings sat by, enjoying the sweets and peering at the babies, then at us. We were finally led back to the head midwife’s office. She sat us down and began describing hospital procedures.

Given the restrictions, their policies, procedures, and results were impressive. It was the conditions that were so hard. Many of the staff came from out of town, which meant living and working in the hospital for weeks at a time, hoping that at the end of their month-long shift they could negotiate a ride in an ambulance to get through the checkpoint and home to see their own children. One midwife, Fatima, explained that she lived in Tulkarem, thirty minutes away. Except that now, because of the roadblocks, it was six or seven hours away by five different taxis, and a two-kilometer walk for good measure. They were not complaining about conditions, they said; things were good for them compared with others, and at least the hospital, being an UNRWA institution, was adequately supplied so they didn’t have the extra worry of running out of equipment and drugs. As long as the soldiers at the checkpoint permitted.

At one stage the head midwife, who had already spent the morning plying us with sweet coffee, suddenly had a thought. She leaned far out of the office window and called to some invisible person to fetch guavas from the market. They appeared minutes later, and the midwife smiled with pleasure. She sat, portly, homely, peeling the fruits for us, handing us slice after slice, fresh and scented, on the tip of her knife. The guavas we were eating were the last crop Qalqilyans would be harvesting, she said. The trees were on the other side of the Barrier.

The Barrier and the checkpoints ruled everything, she told us, and destroyed everything. It wasn’t just the crops that were on the wrong side; it was also the many Palestinians who relied on Qalqilya for services. Cut off from its hinterland, Qalqilya had been condemned to death.

As we drove away from the hospital, I noticed an old signpost near one of the settlements. I could just make out “Qalqilya” printed on it, but someone had daubed swirls of black paint over the word to make it disappear, as though the town would take the hint and follow suit.

After dropping Laura at Damascus Gate, I went home and called Andrew. We arranged a weekend away. There is plenty of solitude to be found in the tiny land of Israel: north to the verdant Galilee or south to the Negev. The Negev sits in a wedge at Israel’s base, dotted with remnants of ancient civilizations. Here the Nabateans plied their trade routes, building khans to shelter camel trains from the elements and wild animals as they wended through the desert, loaded with exotic goods, flocks trailing in their wake. Here stood great cities like Mamshit and Avdat, whose irrigation schemes had tamed the desert centuries ago, and now the desert was dry again. We slept in a Bedouin tent and watched the flies change shifts with mosquitoes and then swap back again the following morning.

Later that week Andrew came home in the evening and looked at me as I sat at my desk. He stood there, hand in his hair. I thought someone must have died. A plug of dread balled in my stomach.

“I have to leave.”

“What?”

“I’m being sent away. To Senegal.”

“Senegal?” Where was that exactly? But at least no one was dead.

UN Headquarters in New York wanted him to spend six months helping to set up its new West Africa office based in Dakar and covering sixteen countries, many of which seemed to be in constant crisis. And then he would return to his post in Jerusalem. So the rest of us would stay. Jobs and schools meant stability, and he would come back every month to see us and to keep his current unit on track.

Everything was changing. In its campaign to free the world from terror, the US administration was linking Saddam Hussein to al-Qaeda. The Israeli government was linking Iraq to the Palestinians, publishing reports of financial aid from Iraqis to Palestinians. Saddam and Osama, Saddam and the Palestinians, the Palestinians and al-Qaeda: all one confusing pot of terror to scoop into and stir about. We, in the middle, were receiving alarmist calls from family reacting to the foment. Time to think about moving back “home,” they were saying, guardedly, but increasingly strongly. Being whipped up, they were whipping us up.

I went numbly to Nablus with Laura the next morning. The new posting had been confirmed: Andrew was to go to Senegal in two weeks’ time. A civil war had just started in Côte d’Ivoire; there were problems in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria. I met Laura at our rendezvous in north Jerusalem, outside a tiny post office on the old road that was now sidelined by the newly finished settler highway and stilled by checkpoints. We couldn’t risk driving ourselves to Nablus—too many checkpoints. We would use taxis, and if checkpoints were blocked we would abandon the taxi, walk across, and take another on the far side, then on to the next. People buzzed about us as we waited for the first driver. The staff of the cab company brought coffee, and helped me park my car in an unobtrusive slot in a side street.

I sat in the taxi, thinking about being alone in Jerusalem. My head filled with separation, situation. Nablus is north of Jerusalem and Ramallah, not far, but for many it is an impossible journey. Another impossible distance, Jerusalem to Senegal. Maybe the whole family should move to Senegal for six months. There was a great deal of our research program left to do. The road to Nablus winds through hills of olive groves and almond orchards, pink in springtime with violets under the trees, but now dusty after the long summer. The conflict so visible: Palestinian villages in the valleys, Israeli settlements on the hilltops, squads of IDF vehicles on the road.

The driver, with typical insouciance, quipped: “What’s going on here? Anyone would think there was a war on.” Laura and I had foreign passports, but the driver, who had managed to get us so far, had no chance of taking us through the notorious checkpoint, Huwarra. We switched to another vehicle. Senegal, I was thinking. It’s so far away—and no direct flights. No driver dared go too near the soldiers for fear of becoming another victim. Soldiers routinely picked on taxi drivers, who might end up beaten up, their keys confiscated, or their vehicle impounded.

Laura knew her way around Nablus, a lattice of the very old and the sharply new, lying in a valley with steep hills looking down on us. We found our way past shop windows of shoes and sheets and plastic toys, up two flights of concrete stairs and into an outpatient clinic. Women sitting with their babies and bellies, and nurses busying round them, looked at us momentarily. The doctors were stoical. They talked of the way the conflict had affected their patients. I wasn’t concentrating. I had always thought medical terms were a code, a way of conferring uniformity on to a range of signs, symptoms, and syndromes and what to do about them so that everyone knew, with precision, what everyone else was talking about. Occasionally medical language was for obfuscation: to spare the patient too much frankness all at once. Fluency in the code gave entry into a club of sorts, a club of Latin and Greek roots and stems—why say “blood in the urine” when you can say “hematuria?” Senegal? Why did he have to be sent to Senegal?

Here the medical code was for obfuscation of another sort. By using terms like “maternal mortality,” obstetricians were able to discuss the dead mothers without confronting the cause too bluntly, and when I tuned into our host, Dr. Salim, he was talking about the “decrease in prenatal care translating into increased perinatal morbidity and mortality.” This code gave him control over the anger he felt at the cruelty of the checkpoints and closures. It was part of a far broader barrier Palestinian doctors put up against their rage. Israeli doctors used the same tools to protect themselves against their anger when they were dealing with the maimings and mutilations inflicted by suicide bombers: the young woman turned overnight into a “monster,” her face a patchwork of skin grafts; the children with stumps instead of limbs.

Medicine often means dealing with the cruelty of “nature,” its brutishness and inevitability. Sometimes there is also “avoidability” to deal with: the consequences of road accidents, domestic violence, alcohol. But here dealing with the avoidable was excessively painful—the avoidability of suicide bombs; the avoidability of death by closure, checkpoint, and collective punishment. Dr. Salim’s training and early professional life—in England, as it happened—had not prepared him for his patients dying before they could get to him, to medical safety, “because of the stroppy mood of some Jewish kid with a gun at a checkpoint.” There, he’d said it. Then he flipped back into code.

“Pregnancy,” he added at the end. “The minute the women here get pregnant they get worried. In Britain when women get pregnant they go shopping; in Palestine they get terrified.”

At the main Nablus hospital the midwives were slumped on metal chairs in the delivery room. Six delivery beds were lined up along the oblong room, each had its curtains swiped back against the head of the bed. Two were occupied. The new mothers lay as they had delivered, a sheet pulled up over their pudendae—code again—legs akimbo. One was cradling her baby. Another newborn lay wrapped in pink on a shelf under a warming lamp.

“It seems like a quiet moment,” I said.

“If you’d been here an hour ago,” said one midwife, “we’d have had you with your sleeves rolled up. Every bed was full and only three midwives, all of us crazy—and it’s been like that for I don’t know how long.”

A laboring mother was brought in and the midwives turned their attention to her. I left, and met a doctor in the corridor outside the room. He was leaning against the wall, holding his head.

“No, today hasn’t been a good day,” he said. “We had a mother come in at eight and a half months this morning. She had been tear-gassed at the checkpoint and the baby died in utero. I’ve no idea if this was cause and effect, but for her—well, she’ll live the rest of her life hating the Israelis for killing her unborn child.”

He told me about his years of training in Russia, and how eager he had been to come back to Palestine and make his contribution. “Now look at me. I haven’t been home in a month—I haven’t been out of this building in a month. If I’m lucky I might get a ride in an ambulance so that I can see my family. The only other way is to make a break for it across the fields—and I’m not trying that again.”

“What happened?”

“Once I did that—me, a doctor—I was running and the army was shooting at me and I knew I was going to die. One hundred percent, I knew. And that very day a pregnant woman had been killed when the IDF fired on her ambulance—they claimed the ambulance hadn’t stopped... and I just thought, what’s the point?”

“Was it during curfew?”

“What are you talking about, was it during curfew? What’s curfew?—I’m talking about a doctor trying to get home from work and a woman in labor trying to get to the hospital. In an ambulance. I nearly get shot, she gets killed. By what, why? This is our city. It’s miles from Israel. They put on curfews so we can’t move in our own cities?”

“Suicide bombers have come out of Nablus and attacked Israelis...”

His face opened in astonishment. “You find this amazing? Can you really be amazed if some Palestinians want to hit back at the occupation, the collective punishment, the daily killing? Every day they kill us, every day, and no one says a thing in your world.” He looked at me. “Are you one of those who thinks Palestinian blood is cheaper than Jewish?”

“I...”

He didn’t want to hear. “Come on, does anyone know what’s going on here? Do people know? Tell me honestly. Do they understand at all?”

“They...”

“Where else in the world would you find a quarter of a million people not permitted to leave their homes? Sometimes we can’t even leave one room—for day after day after day—in one room. In April we couldn’t go near a window. We would be shot. Think about it.”

Curfew... the thought of being trapped... Trying to imagine what it meant to be locked inside the house when the children were begging to go to school... or just begging to be allowed outside, through the door into the open air. What did they do, hour after hour, day after day? How did they survive the suffocating feeling, hearing the church bells calling them to prayer, or the muezzin from the minaret, putting a hand on the door to push it open and run out—but then stopping themselves? Knowing their families were a street away, or half a town away, yet trying to explain to the children why their grandfather would not be coming with the traditional presents and food for Ramadan. Explaining to my own children that their father would be going away for work, that was easy enough. But explaining to Palestinian children that Christmas had been canceled and there would be no celebration, no games or singing, no gatherings, because the IDF wanted them all to stay at home and not to leave the house, not even to get food, or to go to the doctor if they got sick?

Oh God, and on the other side, the Israeli children whose fathers or mothers or brothers, sisters and grandparents were dead, blown up. Or maimed, mutilated in the suicide bombings. All the avoidability. And the interminable suffering.

On our way out of Nablus Laura and I bought shawarma—lamb sliced off a spit into a fold of bread—in the market. We walked a little way into the kasbah to take in the ancient buildings, the heavy stone and delicate carvings,4 then wandered about the fruit and vegetable market, found a servees taxi to take us out of town and rejoin our own taxi.

At the checkpoint one soldier was shouting with rage at anyone who tried to approach. No one was going anywhere. It is very hard to know what to do when you face a soldier in a fury blocking your route home. After all, you have to get home. Laura and I moved forward and he screamed at us: “When I tell you to WAIT—you wait, and you WAIT until I tell you to stop waiting. Do you understand!” Storming up to us, still shouting “Get back! You cannot pass.”

Gently, I asked, “Until when? You see, I have to pick up my children from school...”

“Until I say you can pass! It doesn’t matter what you have to do.” His face was puce, his helmet bouncing in his rage. “Now GET BACK! Understand my words?” Not only his words: two vehicles driven by settlers sped through. We turned to go back but were beckoned forward by another soldier, who looked at our passports and gave us to understand that his colleague was having a bad day. A third soldier came up, calmed down the screamer and led him away, motioning for us, the foreigners, to pass through.

On our way home the taxi driver pointed out his village and its olive groves, and the fields along the way that were his but that he no longer dared harvest. Settlers had attacked him, his family, and his crops too many times and they had given in. “I cannot work my land now,” he explained. “If I try to harvest my olives, the settlers shoot at me, and the army does nothing.” Along the road we looked up again at the tops of the hills, at the settlements up there, looking down on us.5

There was one weekend left before Andrew left for West Africa. We flew to Istanbul and visited Andrew’s cousins who lived there. I was still thinking about curfew. I had thought curfew was simple. Simply locked indoors. The Nablus doctor had said they were being shot at while in their homes, and a number of people had died that way, including Lana’s mother. It wasn’t just prison: prisons offer some safety. Here families were not safe even inside their own houses.

In prison, but you have to fend for yourself, forced to remain indoors for days at a time, a brief release for an hour or two, and then several days’ curfew again. In the grinding heat of the Middle Eastern summer, a family of maybe fourteen people in two rooms, with no running water and no air conditioning, you run out of baby milk because the army didn’t tell you how long the curfew would be, and anyway you have no money to buy food, or milk, as you haven’t been allowed to work for months, and if you step out you may be shot on sight.6 Then, if someone does fall sick, you have to hope they don’t get too sick, because if they do then you have to risk breaking the curfew to get help. And the worry. And all the time the children scream because they are hungry and bored and just maddened with frustration.

The words of one Israeli woman came back to me: “You know what the Palestinians do under curfew?” she asked. “They make babies.”

Andrew’s cousins showed us some of the glories of the Ottoman Empire, the vast mosques and churches with exquisite mosaics. They gave us lunches in the souk and sumptuous dinners overlooking the Bosphorus. How was a curfew “lifted?” How did the message get through to each family that they had a couple of hours to stock up before curfew was imposed again for days on end? Palestinian TV stations were one way, but sometimes the IDF cut the electricity. There was word of mouth, but you couldn’t move; mobile phone calls, but how to charge the batteries with no power and anyway the messages were often wrong. People missed the lifting, or went out when the curfew was still on. Some were shot getting to the shops. The Nablus doctor had laughed sourly: “You know when the curfew is on again because you get shot at in the street, or your water tank is pumped full of holes. The IDF can make it very clear like that.”

Before we left Istanbul we had a drink with the historian Norman Stone. We chose arak (raki in Turkey) and sipped its aniseed strength as we talked. Curfew came up again—curfew that had lasted in some places for eight days without one break. Was he aware, I asked of any other curfew so draconian in the last hundred years? The professor thought it unlikely. “Maybe in Eastern Europe toward the end of World War Two.”

Landing in Jerusalem again, we drove home and saw Sholto take his first steps—four of them—in the garden. He didn’t like to try walking inside the house on the glassy marble tiles. He liked to be outside on the limestone flags. In the fresh air.

* The Barrier, declared Ha’aretz, “hijacked the original idea of a security fence and twisted it into an invasive and provocative fence running deep into the West Bank,” confirming that “the networks of settlements to be surrounded by the fence and situated deep inside the territories were always meant to prevent the formation of a viable Palestinian state.”2 For a Ma’ariv commentator, “The pointless presentation of the fence route is part of Israel’s general policy; speaking about security yet really intent on occupation, settlement, and annexation. As with the fence, so it is with the territories: Israel’s friends would not criticize if it were acting in the security interests of its citizens, but they cannot stand actions like establishing settlements, land expropriation, and annexation.”3