THE BISHOP, COMSTOCK, AND JUVENILE DELINQUENTS

NEW YORK CITY was abuzz after Bishop Simpson delivered his January 1866 oration, which he had titled simply, “New-York: A Mission Field.” His primary intent was not controversial, for Simpson wanted mostly to draw attention to the bounty of souls in need of salvation throughout the city. As some indication of the potential harvest, he pointed out that the number of his Methodist Episcopal flock barely equaled that of the twenty thousand prostitutes who swarmed through the city’s streets, brothels, assignation houses, concert saloons, and dance halls, all presumably unredeemed.1

His count (which implied that one of every six young New York females was a prostitute) immediately compelled attention, and authorities joined in a chase for valid statistics. The secretary of the City Mission filed a report in the New York Times three days after the sermon that totaled the prostitute population at ten thousand, supported by a business infrastructure valued at five million dollars. (By way of comparison, there were also ten thousand drinking establishments in the city with gross annual receipts of five million dollars, a figure that exceeded the annual police budget by 250 percent.) The heaviest authority to weigh in was John A. Kennedy, commissioner of the New York City Police force. In a lengthy response filed five days after Simpson’s sermon, Kennedy declared that the bishop’s charge had prompted him to order a census of the city’s prostitutes. That study found that there were 621 brothels in the city, 99 assignation houses, and 75 disorderly concert saloons “of ill repute.” Prostitutes numbered 2,670; adding in the 747 pretty waiter girls who were likely prostitutes made for a grand total of 3,417. In August, the New York Times reported yet another number, this one attributed to the superintendent of the Home for Fallen Women (which was in a building that formerly housed a brothel and was strategically located just across Broadway from Harry Hill’s). Although the Home for Fallen Women had already rescued seventy-five women from the streets, work was still to be done, for the superintendent estimated there were four thousand full-time “public prostitutes,” something like the same number of part-timers, and an equal number of “kept mistresses and semi-respectable women”; or, in his round numbers, there were about fifteen thousand prostitutes in New York City.2

In all likelihood, Kennedy’s low number was in the best interest of the police department and Simpson’s high number was intended to motivate his congregation. More realistically, an accurate census would have counted somewhere between six thousand five hundred and thirteen thousand, or about one of every twelve young women. Significantly lower than Simpson’s ratio, this was still a number that commanded attention.3

The issue caught one politician’s eye. Elected to the State Assembly in December 1866, John C. Jacobs, a twenty-nine-year-old Democrat from Brooklyn, brought before his fellow legislators on January 8, 1867, a resolution calling for New York City’s Sanitary Committee (which consisted of physicians) and Police Commissioner Kennedy to file official reports on prostitution in New York City. Jacobs’s move was part of a long-term strategy to legalize prostitution, tax it, and ensure that the women involved underwent regular physical examinations, as was common practice in parts of Europe.4

The State Assembly adopted Jacobs’s resolution. Kennedy published his report in late February, which contained some of the predictable warnings about how male patrons were being victimized by prostitutes, i.e., trafficking with prostitutes leads to debauchery, then overindulgence, then the shirking of business and family responsibilities, and finally crime. Since Kennedy considered the providers of sex to be the source of the problems, he recommended that heavier penalties be slapped on madams, prostitutes themselves, and the owners of property who knowingly allowed their premises to be used for prostitution. He also attached a new census to his report, claiming that in Manhattan and Brooklyn there were 575 brothels, 93 assignation houses, 38 concert saloons, 2,588 prostitutes, and 336 waiter girls. Conveniently, these numbers represented a decline in prostitution from January 1866, clear evidence (in Kennedy’s view) that policing efforts were paying off.5

As mandated by Jacobs’s resolution, the Sanitary Committee also issued a report, one with far more significant recommendations. Statistics on an epidemic of venereal disease was point one: 8 percent of Union soldiers during the Civil War had venereal scars (only 1.05 percent of such soldiers were from rural areas, but 12.25 percent of those from cities were infected), and Germans were more likely to have venereal disease than Irish or (native-born) Americans. The committee’s report then moved on to four recommendations, two of which proposed that the medical treatment of venereal diseases, whether of the client or the prostitute, be made freely and easily available, with program costs to be borne by the city. Next it suggested that all those who managed houses of prostitution or assignation houses be registered, along with all prostitutes; the register, which would be maintained by the police, would not be open to public inspection. Proposal four recommended that all houses of prostitution and all prostitutes be subject to regular inspections by the Board of Health.6

Jacobs drew points from both reports and fashioned a bill that he put before the Assembly on March 6, 1867. In the spirit of compromise, it called not for the licensing of bawdy houses but for penalties to fall on those who maintained them and those who owned property used for prostitution. Furthermore, the police would be required to maintain a list of all bawdy houses and the women in them. The bill was amended in committee to mandate medical examinations of all females in the houses and, if found diseased, to provide for tax-supported convalescence in a medical facility.7

Heavy lobbying by those involved in New York’s prostitution business aimed at killing the bill. Fearing that the bill would pass, they worked with Assemblyman David G. Starr, an upstate Democrat, to frame a different bill that authorized the licensing of all bawdy houses, the appointment of a commission to regulate them, and the empowerment of a board of medical inspectors. The bill had two measures favored by the industry: 1) the de facto legalization of prostitution, and 2) licensing fees set high enough ($500 for a “first-class” house; $250 for a second-class one) that they would presumably drive lower-class houses out of business. Curiously referred to the Assembly’s Committee on State Charitable Institutions, it was thought by the New York Tribune to be the “cheekiest” bill yet presented that year, and by the New York Times as unlikely to pass. In fact, it was never reported out of committee.8

Jacobs’s bill, however, was reported out to the Assembly, but with a negative recommendation from a subcommittee of the entire Assembly. The Assembly voted the bill down; and the state of New York took a pass on its only serious opportunity to legally recognize prostitution in New York City.9

Although nothing much came from these efforts initially (except for the advancement of young Jacobs’s political career), media and public attention was now sharply focused on the issue. One result was yet more statistics on prostitution in the city. The New York Times counted fifteen thousand prostitutes in the city in August 1866; the Buffalo Commercial soon after reduced that by a touch to only fourteen thousand. The New York Tribune in early February 1867 figured a “grand army of twelve thousand six hundred criminal women” and put that number in a telling spatial context: “placed in line [with] two feet of space allowed to each, the painted procession would extend from the Battery to Fortieth-st.” Commissioner Kennedy conducted yet another census and this time recorded a mere 2,924 prostitutes and suspect waiter girls. Other numbers thrown about in 1867 were two thousand seven hundred; five thousand; ten thousand; twelve thousand; twenty-one thousand; and twenty-five thousand. The obsession with numbers was not entirely misplaced, for the decade of the 1870s represented the zenith of commercialized sex in New York’s history.10

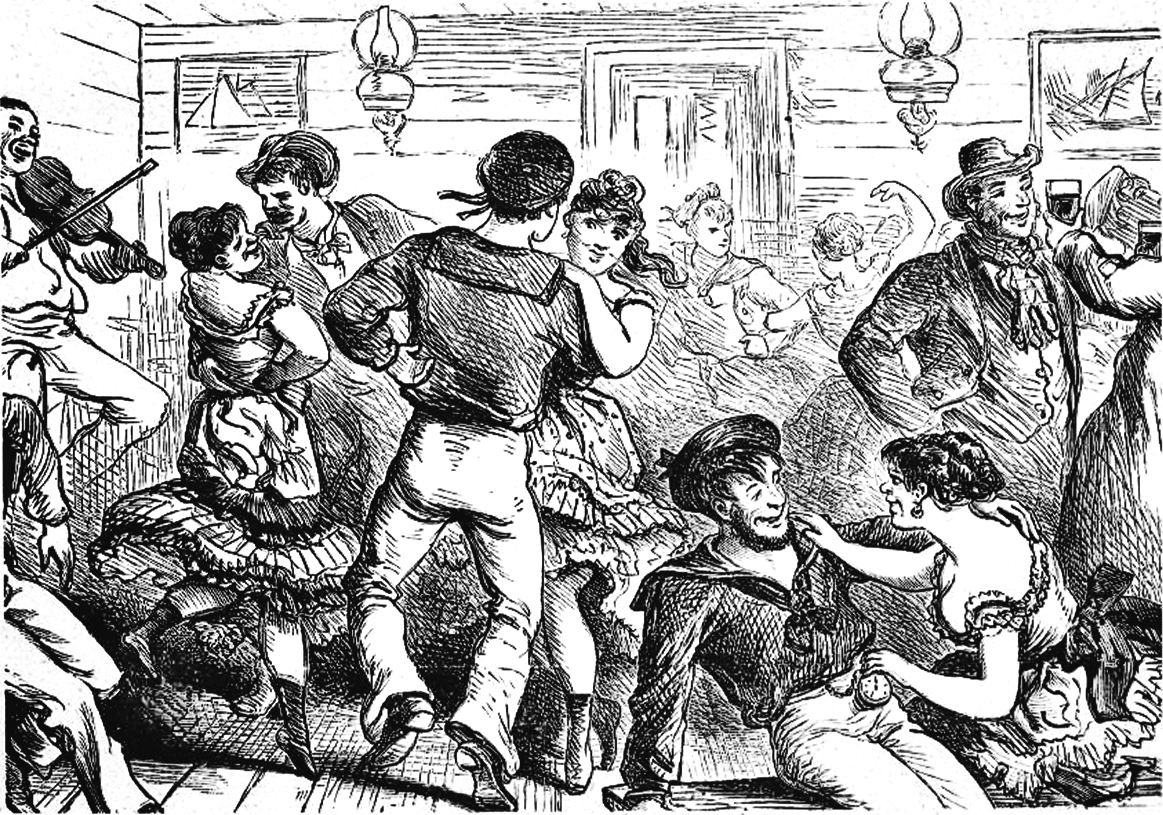

The services of prostitutes could be procured in many places. Dance halls, as in the past, were prime locations, especially for the lowest classes and for sailors freshly in port, who were known for seeking the “greatest amount of pleasure within the shortest possible time.” Concert saloons during this time were little or no better. In these places the dresses of already scantily clad pretty waiter girls shrank during the decade until they were finally “microscopic,” whereupon “immodesty [threw] off as it were the last fig leaf” and celebrated lust and revelry, according to one reporter. And, conveniently, many concert saloons arrayed “wine rooms” around the floor, furnished with a table, two chairs, a sofa, and a door that locked.11

And if still unsure where prostitution’s business might be found, there was always the Gentleman’s Companion (1870), fifty-five pages and sized to fit unobtrusively in a pocket. Descended in a line from the sporting press of years before, the Companion contained the names and addresses of 150 brothels and concert saloons, ratings for many of them (nine were “first-class”), the numbers of prostitutes in each, and information on any special qualities or skills held by the women. Of course, the Companion made emphatically clear that the publication’s purpose was that “the reader may know how to avoid” such places. Readers, for instance, needed to be warned against the second-class house at 127 West Twenty-Sixth Street, which had little reason for special attention but for the fact that a bear was kept in the cellar, the purpose of which “may be inferred.” Things were better right behind that house, at 128 West Twenty-Seventh Street, where Madam Lizzie Goodrich’s five attractive boarders had dispositions that would “tend to drive away the blues.” And if a naive visitor to the house had been overcome and entrapped by one of the prostitutes, a physician was always on hand to tend to any health concerns. Readers also learned from ads about the erotic books for sale at John F. Murray’s establishment on West Houston (Fanny Hill, Fast Young Lady, Annie or the Ladies’ Waiting Maid, among others). And that Dr. Charles Manches, on Broadway, offered great prices on a dozen “French Male Safes,” with the buyer given a choice of base materials—skin or India rubber. Clearly, sex and sexuality in that day’s New York City as practiced by the many was not at all like the polite prudery widely imagined for them today.12

“Jack Tar Among the Land Sharks.” Image from Samuel Anderson MacKeever, Glimpses of Gotham and City Characters (New York: Richard K. Fox, 1880).

Because of prostitution’s proliferation and its ubiquity, many New Yorkers were genuinely appalled by what they saw around them. They felt that to bring a vice epidemic into the blinding light of a more moral day a crusade was needed, one to be headed by a strong-willed, right-minded captain.

Enter Anthony Comstock.

Comstock was of New England Puritan stock, with his moralistic perspectives sharpened by allegiance to many of the period’s social-reform movements, particularly abolitionism, temperance, and pseudo-medical reforms involving bodily purity. He had moved to New York City shortly after serving in the Civil War (where he alienated many of his fellow soldiers by pouring his rations of whiskey on the ground instead of sharing them). There he joined the Sons of Temperance in Brooklyn and found a job selling dry goods.13

New legislation at both the federal and state level pointed Comstock toward his life’s purpose. In 1865, the U.S. Congress passed a law banning the distribution of obscene publications through the postal system. The New York State Senate in 1867 went further and considered legislation to suppress the publication and distribution of indecent images as well. Such a bill was forwarded to the State Assembly and was widely expected to pass, but the document went “missing” from the clerk’s desk and could not be brought forth for consideration. Another year and another legislative session, and in January 1868 Senator John O’Donnell introduced into the Senate a bill banning the dealing in or circulation of obscene materials of all sorts and any object or artifact of “immoral character.” It was passed by the Senate in March and the Assembly toward the end of April. Within its wording there was no effort to define “immoral,” “indecent,” or “obscene”—apparently one just knew it when one saw it.14

Later in 1868, with those laws now on the books, Comstock’s personal diary contained an annotation on how an acquaintance had been “led astray and corrupted and diseased” by indecent literature. The Puritan in Comstock billowed and he immediately sought out the seller of the literature, Charles Conroy. Comstock then bought from him an obscene book. With the evidence literally in hand and a conveniently placed police captain nearby, Comstock had Conroy arrested and his stock of immoral materials seized and destroyed.15

Comstock must have been thrilled with his easy victory, for he soon became a vigilante force of one. His method was always the same: identify sellers of immoral literature; incriminate them; get their stocks destroyed; extract legal justice. Among the many he found peddling illegal material during this time was, once again, Conroy, which ended with a result similar to that in 1868. In 1874 Comstock went after Conroy for the third time. Perhaps weary of his antagonist’s tenacity, Conroy retaliated, produced a small knife, slashed at Comstock, and cut his face from the temple to the left chin. Undeterred by mere mortal harm, with blood spurting from the cut, Comstock seized Conroy and again had him arrested. He would wear a distinctive scar the rest of his life.16

Comstock’s success at suppressing obscene materials prompted renewed interest from the U.S. Congress. Encouraged by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and other organizations to seek stronger federal legislation against the immoral trade, Comstock lobbied in Washington for the “Act for Suppression of Trade in and Circulation of Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use,” which was subsequently passed on March 1, 1873. A much-strengthened successor to the 1865 law, it made it illegal for anyone to use the postal service to send obscene materials, any information on obscene materials, contraceptives or information on preventing pregnancies, abortion medicines or information thereof, “rubber goods” (i.e., condoms), even medical anatomy books. For good reason, the Act came to be widely known as the “Comstock Law.” In recognition of his vigilance in suppressing obscene literature, the postmaster general appointed Comstock a special agent of the postal service, a position he would proudly hold for forty years.17

Comstock’s newfound notoriety garnered broad citizen support for the establishment and legal incorporation in May 1873 of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, with support from J. P. Morgan and the YMCA. The Society’s seal made the mission clear: on the left side, an image of a handcuffed purveyor of obscene materials being taken away by a policeman; on the right, a derby-hatted, upstanding citizen burning smut.18

Comstock now had the ways and means to broaden his campaign. Abortion came into his line of sight, and in 1874 he boasted of having arrested eleven abortionists in three days. Then in 1878 he turned his attention to the most notorious, best-known abortionist of the era.

Madame Restell had served out her prison sentence in 1841 after George Washington Dixon engineered her indictment and subsequent conviction. She soon returned to providing backroom abortions, although now with more circumspection. Restell still advertised her services in New York newspapers, but in densely coded language: “A Certain Cure for Married Ladies, With or Without Medicine” and “infallible French Female Pills.” Her illegal and dangerous work over four decades had made her an exceedingly wealthy woman but also earned her the title of the “Wickedest Woman in New York.” And she was now in Comstock’s crosshairs.19

His method, as almost always, was to gather incriminating evidence incognito. In this case, Comstock posed as an impoverished husband desperately seeking Restell’s French Female Pills for his wife. Once purchased, he brought in waiting police officers and had Restell arrested. Ann Lohman (her real name) was then sixty-five and had battled against police and reformers from even before Dixon. Comstock’s pursuit and arrest of her must have been a final indignity. The day after her arrest she was discovered in her bathtub, dead from self-inflicted knife wounds. To Comstock, never the empathetic humanitarian, that represented justice—“A bloody ending to a bloody life.”20

Comstock liked to tote up and broadcast the results of his crusades. Among his hauls: the destruction of 320,000 pounds of obscene literature, 284,000 pounds of publishers’ plates, 4,000,000 pictures (including 186,000 pounds of indecent postcards), and enough people arrested to fill a passenger train of sixty-one coaches. But he seemed to have overplayed his hand when he boasted that Madame Restell was the fifteenth person he had driven to suicide after exposing criminal behavior. Public opprobrium was widespread after this comment, something of a shock to Comstock. Ezra Heywood, an anarchist who promoted free love and was long a special target of Comstock’s crusades, wrote tellingly of the man, his mission, and his methods: “This is clearly the spirit that lighted the fires of the Inquisition.”21

There had been crusaders and societies of crusaders before, of course. By and large these people and their organizations were typically conservative in their actions and reserved in public demonstrations of righteousness. Comstock, on the other hand, realized that citizens and societies of organized citizens might function as aggressive vigilance groups that directed the attention of authorities toward targeted problems and, moreover, could and should lobby lawmakers for strong laws governing personal and social behavior. The influence of Comstock and his aggressive approach would be felt well into the twentieth century. Indeed, one wonders if laws such as the 1910 Mann Act (prohibiting interstate trafficking in sex), the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, the widespread banning of prostitution districts (1910–1917), or the 1919 Volstead Act (prohibition of alcohol) would have come to pass without his towering influence.

The Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents in New York City, although a much older institution, soon adopted some of the methods perfected by Comstock. New York’s high-minded had long been concerned about incarcerating young people who had committed petty crimes alongside seasoned, adult criminals. To address this problem, some citizens in the mid-1820s helped establish a House of Refuge for young offenders, an institution that would later be called a reform school and today a juvenile detention center or a halfway house. The idea was to provide juvenile delinquents with a safe and supportive peer-group environment, then train them in a trade that would lead to a meaningful place in society.

Bricks and mortar plus maintenance and staff, the House of Refuge was an expensive proposition. It was initially supported by members of the newly incorporated Society, the federal government (which loaned and later sold an unused building to the Society), the State of New York (which had passed a bill in 1824 offering assistance in the amount of two thousand dollars per annum), and commensurate help from the municipal government. Budget support was modified in 1829 when the State Assembly passed legislation directing the New York City commissioner of health to channel funds to the Society, including a proportion of licensing fees paid by city theaters and saloons. As a result, the Society’s ledger sheet in 1830 showed fifteen hundred dollars from fees paid by three unnamed theaters. In addition, the Society that year benefited from licensing fees levied on 2,842 taverns, which accrued to the account books a total of $4,263. A funding pattern was thus established that would prevail for many decades, the policy’s rationale being that if entertainment and alcohol provided the soil in which vice, criminality, and juvenile delinquency flourished, let entertainment and drink pay the social costs.22

In 1861, funds to aid the Society from “Theatre licenses, &c.” amounted to $8,081.80, with an additional amount from the Board of Education of $5,199.60. Then came the Anti-Concert Saloon Bill of 1862, which outlawed alcohol in places of public amusement. This had the effect of severely cutting revenue from licensing fees as theaters and saloons could now seek a liquor license or a theatrical license, but not both. In 1872, for example, the Society received funds from theatrical licensing fees of only $1,365.08, leaving its budget more than two thousand dollars in the red.23

It was soon clear that state legislative efforts to regulate vice by removing alcohol and pretty waiter girls from theatrical events clearly had not worked as intended, for many establishments (and the police) simply ignored the law. The legislature addressed the issue on May 22, 1872, when it passed “An Act to Regulate Places of Public Amusement in the City of New York.” Among other things, the Act declared that it was unlawful to mount any “interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, ballet, play, farce, [blackface] minstrelsy or dancing . . . equestrian, circus, or any performance of jugglers or rope dancing, acrobats” without a theatrical license. To obtain a license, a place of public amusement paid five hundred dollars, which amount “shall be paid over to the treasurer of the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents in the City of New York, for the use of the said Society.” Without said license, each performance was subject to a penalty of one hundred dollars. Then came the clause that gave the Act heft: “which penalty the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents in this city is hereby authorized to prosecute, sue for and recover for the use of said Society, in the name of the People of New York.” The legislature essentially turned over to the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents legal incentive for policing theatrical performances in New York.24

To no surprise, the Society soon sent undercover agents into suspect places without theatrical licenses: beer gardens, medicine shows, sponsored balls and parties, museums, dens, and most any other places where illegal performances might occur. There they waited for and documented any infraction of the Act. After passing evidence to the authorities, the Society collected the fines and any subsequent licensing fees.

And it paid off. Within a year of the Act’s passage, the “Theatrical Licenses” line in the Society’s annual report had increased by more than one thousand percent to almost fifteen thousand dollars. By 1878 it was $22,457.56. And in 1880, the Society would benefit to the amount of about thirty-five thousand dollars from licensing fees and fines.25

To gather and consolidate evidence, agents were required to file reports with the Society on what they saw and heard. Those reports would then be edited into affidavit form and submitted to the courts. As a result, some details of the investigations have survived in the affidavits, although the reports themselves have not. For example, agent Charles R. Groth visited the Liverpool Variety Theatre at 27 Bowery on September 13, 1881, and testified that it was a “combination of a ‘pretty waiter girl’ saloon and a theater and is the resort of a low class of people of both sexes.” Rudolph W. Faller was with Groth and repeated the testimony in his affidavit. Affidavits in hand, the Society stood to be at least one hundred dollars richer.26

The Bowery Varieties Theatre at 33 Bowery received special attention from Society agents. In 1879, one agent described the “concert room and theatre.” There was a raised stage, footlights, a drop curtain, and an orchestra of piano, violin, cornet, and drums. Performers included four men and four women, the latter of whom wore tights under their fancy dresses. In keeping with contemporaneous entertainment traditions, the men were in blackface, dressed in minstrel costumes, and played the tambourine and bones. The ensemble sang songs and told jokes that consisted mainly of a string of bad puns. The minstrels were followed by a musical interlude, then another act of three men (one dressed as a woman) took the stage and entertained the audience of about 150 persons with their songs, dances, and acrobatics. A later report noted that there was a female singer who wore a short dress, fancy shoes, and colored stockings, and that she pranced up and down the stage. Her act was followed by a blackfaced clog dancer.27

In May 1882, an agent visited the as-yet-unlicensed theater again. He testified that there was no admission charge, which suggests that the Bowery Varieties functioned more as a disorderly concert saloon than a bona-fide theater. “Private boxes” were noted (probably available for use by the hour), and a female singer entertained with “The Pitcher of Beer,” a popular song from 1880 by Edward Harrigan and David Braham, a clear violation of the Act.

Each night in the week and week in the year,

With a heart and a conscience that’s clear,

I’ve a friend and a glass for to let the toast pass,

As we drink from our pitcher of beer.

Another woman then launched into “Awfully Awful,” a somewhat risqué English music-hall song. The program closed tearfully with a maudlin rendition of “A Violet from Mother’s Grave” (1881).28

Although the Society did not need to provide evidence of immoral behavior to claim the fee and fine, it seemingly could not resist. The last item on the preprinted affidavit form concerned the size of the audience, which agents then typically used to note the nature of the audience, specifically the women in it: “including many females who sat at tables drinking and smoking with male companions” was a common formulation. Agent Sooney made sure to mention that “about one hundred persons were present” and the “females [were] of loose character.” References to the relative virtue of audience females occurred so frequently in the affidavits they strongly suggest that while some male patrons might have been there for the “concert” or the “saloon” aspect, many of them were there for the women.29

The agents of the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents also occasionally included the names of entertainers in their affidavits, some forty-one of them from 1879 to 1883 alone. Although most of those named were apparently singers or instrumentalists, several were pugilists who boxed in rings installed in many concert saloons, à la Harry Hill’s. Only a few names among the musicians left much of an historical mark. Then (as now) many loved to make music and dedicated important parts of their lives to the profession, but the bold impression on music history was infrequent.30

Blackface minstrels were almost half of the named musicians. At the Bowery Music Hall in 1879, a quartet of them sang and played the fiddle, banjo, bones, and tambourine, and “besides singing, marked time with their feet, shouted, and the bones and tambourine players did many ludicrous things to amuse the audience.” Some of the blackface acts featured performers of some renown. Vocalist and dancer Billy Emerson, for instance, a popular Irish-born minstrel who first appeared on the stage as a twelve-year-old in 1858 and performed throughout the English-speaking world during a long career, gave stopover performances in New York’s concert saloons. That blackface minstrelsy, more than forty years old in the 1870s, was still a vital presence on the American stage speaks reams of its centrality to developments in American popular culture, to say nothing of its place in expressing race and society.31

“Interior of a Concert Saloon.” Image from George Ellington, The Women of New York; or, The Under-World of the Great City, Illustrating the Life of Women of Fashion, Women of Pleasure, Actresses and Ballet Girls, Saloon Girls, Pickpockets and Shoplifters, Artists’ Female Models, Women-of-the-Town, Etc., Etc., Etc. (New York: New York Book Co., 1869).

In addition to naming entertainers and entertainment genres, agents listed song titles—eighty-six of them from 1879 to 1882—thus providing a useful cross section of the music heard in that day’s concert saloons and variety theaters. They ranged from old ballads (“Sally in Our Alley”) and eighteenth-century patriotic songs (“Yankee Doodle,” “Hail Columbia”) to Scottish and Irish songs (“Scotch Lassie Jean,” “The Irish Fair”) and older popular songs (“Old Folks at Home,” “What Are the Wild Waves Saying”). But by far the majority of songs noted were the day’s most popular, with titles such as “Cradle’s Empty, Baby’s Gone” (1880), “De Golden Wedding” (1880), “Little Log Cabin in the Lane” (1871), “The Mulligan Guard Picnic” (1878), “Silver Threads Among the Gold” (1873), “A Violet from Mother’s Grave” (1881), and “When the Robins Nest Again” (1883).32

Many popular songs heard in concert saloons were undoubtedly performed as published, with a vocalist and a pianist respecting the notes on the printed page. Indeed, there were occasional reports of a “gurgling piano, ring-wormed by wet beer glasses” loaded down with a stack of well-used sheet music, implying that something like straight performances was common. But published songs could also be reshaped to fit the situation. Concert saloons had pianos, but musicians also played violins, cornets, French horns, banjos, tambourines, bones, guitars, and more. With such rich musical resources available, songs must often have been “arranged” or, perhaps more accurately, improvised—made up on the spot and never written down. In fact, the urge toward ad-hoc music-making is a long-standing and salient characteristic of American popular music performance. For instance, Stephen Foster (who had died in January 1864 at 30 Bowery) published “Oh! Susanna” in sheet music form in the hopes that there would be profit from its sale. He wanted the song to be performed as printed in thousands of American parlors, generally by middle-class musicians (often female) who had some training in reading music. But Foster also knew that the song might be (and was) performed by minstrel bands, marching bands, solo fiddlers, and a host of others, all without his sheet music in view, and in an era when performance rights were nonexistent. In fact, the sheet music of that time often functioned more like a musical chart than a musical score not to be violated. In that regard alone, “Oh! Susanna” (1847) was different in actual practice than, for example, the rigorously authoritative score to Chopin’s “Sonata in G minor for Piano and Cello” (also 1847). Popular music was performed in a manner befitting situation, audience, and the musicians at hand. In that way it lived in concert with its time and place.33

Fluidity of performance was also true of the song’s lyrics. Many concert saloon performers surely rendered the text as printed. But many others used the sheet music as a set of ideas, situations, characters, and rhymes—a jumping-off place for extrapolation to topical parody. Beyond that, parody could even veer into the bawdy (or “smutty,” as one agent described the process). Of course, of the three possible permutations of a popular song—printed, topical parody, or bawdy parody—the form most likely to endure as a historical record is the printed. Parodies are expressions of an oral tradition meaningful in the lived moment, with half-lives rarely chronicled and often only implied.

One well-known song heard in the Opera Concert Saloon gives some idea of how far parody could deviate from the printed page. “Dixie” was performed there in 1864 by a pretty waiter girl named Fanny, who was known for “accidentally dropping her cambric and stooping down to pick it up so as to let the young fellows see that there’s nothing artificial about her.” Fanny sang Dan Emmett’s song to the accompaniment of a piano and a fiddle. But her parody version, quite unlike the published version from five years before, told the story of a young gallant who wooed lovely young Nancy by taking her for a boat ride in Central Park. The boat capsized and in the process the gentleman lost his coat, watch, waistcoat, and cash. He kindly escorted Miss Nancy home “to tea” and learned that she too had suffered losses—her teeth, her heavy makeup, and her wig. Months later, the protagonist bumped into Nancy again, this time with a babe in arms. She had been before a judge and the gallant now learned that he was legally a father. As a result:

“An East Side Jamboree.” Images from Alfred Trumble, The Mysteries of New York; A Sequel to Glimpses of Gotham and New York by Day and Night (New York: Richard K. Fox, 1882).

Three dollars a week I had to pay

To Nancy, Miss Nancy,

I never was there I do declare,

And that’s what I don’t fancy.34

In spite of efforts by the agents of the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents and by Comstock and colleagues, the concert saloon sustained its free-wheeling, subversive, sybaritic air through the 1870s. Here, dance-based music long associated with demimonde culture was fluidly conjoined with more genteel popular song idioms of the day, in the process changing how American popular music was made, appreciated, and consumed. Such music gave expressive voice to the voiceless, for deep beneath the dour Comstockian regime, wild music could ignite a jamboree of joy, wit, and camaraderie that revealed puritanical delusions for what they were.35