Chapter 6

Early Contact with the New World (1491–1607)

Colonization of North America (1607–1754)

NATIVE AMERICANS IN PRE-COLUMBIAN NORTH AMERICA

Historians refer to the period before Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the “New World” as the pre-Columbian era. During this period, North America was populated by Native Americans—not to be confused with native-born Americans, a group that includes anyone born in the United States. Five percent of multiple-choice questions test you on this era, so it is extremely important to understand the clash of cultures that occurred between the European settlers and the Native Americans, as well as their subsequent conflicts throughout American history.

Most historians believe that Native Americans are the descendants of migrants who traveled from Asia to North America. The migration likely occurred in multiple waves, from as early as 40,000 years ago to as recently as 15,000 years ago. During this period, the planet was significantly colder, and much of the world’s water was locked up in vast polar ice sheets, causing sea levels to drop. The ancestors of the Native Americans could therefore simply walk across a land bridge from Siberia (in modern Russia) to Alaska. As the planet warmed, sea levels rose and this bridge was submerged, forming the Bering Strait. These people and their descendants eventually migrated south, either by boat along the Pacific coast or possibly along an ice-free corridor east of the Rocky Mountains, and went on to populate both North and South America.

At the time of Columbus’s arrival, between 1 million and 5 million Native Americans lived in modern Canada and the United States; another 20 million populated Mexico. Native American societies in North America ran the gamut from small groups of nomadic hunter-gatherers to highly organized urban empires. In the year 1500, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was more populous than any city in Europe, and both the Aztecs and the Maya are noted for their advances in astronomy, architecture, and art. While these civilizations were located in Mesoamerica, the territory that would become the United States was home to urban cultures as well, such as the Pueblo people of the desert southwest with their multistory stone houses consisting of hundreds of rooms and the Chinook people of the Pacific Northwest who subsisted on hunting and foraging or the nomadic Plains Indians. The first Native Americans to encounter Europeans were smaller tribes, such as the Iroquois and Algonquian, who had permanent agriculture and lived along the Atlantic Ocean; Columbus, mistakenly believing he had reached the East Indies, dubbed them “Indians,” and the name stuck for centuries.

Cahokia

Located near the site of modern-day St. Louis, Cahokia was the largest North American city north of Mexico prior to the arrival of European settlers. In the thirteenth century its population rivaled or surpassed that of any European city, and while it was abandoned a hundred years before the voyages of Columbus, no American city passed Cahokia’s peak population mark until after the United States had achieved its independence. Cahokia was dominated by a huge earthwork known as Monks Mound, an artificial hill 100 feet high and covering 17 acres, consisting of soil transported to the site by hand in baskets.

EARLY COLONIALIZATION OF THE NEW WORLD (1491–1607)

The Early Colonial Era: Spain Colonizes the New World

Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492. He was not the first European to reach North America—the Norse had arrived in modern Canada around 1000—but his arrival marked the beginning of the Contact Period, during which Europe sustained contact with the Americas and introduced a widespread exchange of plants, animals, foods, communicable diseases, and ideas in the Columbian Exchange. Columbus arrived at a time when Europe had the resources and technology to establish colonies far from home. (A colony is a territory settled and controlled by a foreign power.) When Columbus returned to Spain and reported the existence of a rich new world with easy-to-subjugate natives, he opened the door to a long period of European expansion and colonialism.

During the next century, Spain was the colonial power in the Americas. The Spanish founded a number of coastal towns in Central and South America and in the West Indies, where the conquistadors collected and exported as much of the area’s wealth as they could. Under Spain’s encomienda system, the crown granted colonists authority over a specified number of natives; the colonist was obliged to protect those natives and convert them to Catholicism, and in exchange, the colonist was entitled to those natives’ labor for such enterprises as sugar harvesting and silver mining. If this sounds like a form of slavery, that’s because it was.

Spanish and Portuguese colonization of North America was also marked by liberal mixing of cultures, leading to a racial caste system, with Europeans at the top of the hierarchy, followed by Mestizos (those of mixed European and Native blood, Zambos (those of mixed African and Native American heritage) and pure-blooded Africans at the bottom of the ladder. Meanwhile, the strength of Spain’s navy, the Spanish Armada, kept other European powers from establishing much of a foothold in the New World. In 1588 the English navy defeated the Armada, and consequently, French and English colonization of North America became much easier.

Much of early American history revolves around the conflict between Native Americans and European settlers. Europeans were generally victorious. Why? One seemingly obvious answer is that the Europeans had more advanced technology, but this wasn’t actually a major factor. In fact, in many ways, the Native Americans’ technology was superior: Their canoes were far better at navigating North American rivers than any European ship, and their moccasins offered better footing than clumsy European boots. The most important factor, by a wide margin, was disease. Native Americans had never been exposed to European microbes and had never developed immunities to them. Epidemics, such as smallpox, devastated Native American settlements, sometimes killing 95% of the population years before Europeans themselves arrived to mop up the few survivors.

Competition for Global Dominance

Once Spain had colonized much of modern-day South America and the southern tier of North America, other European nations were inspired to try their hands at New World exploration. They were motivated by a variety of factors: the desire for wealth and resources, clerical fervor to make new Christian converts, and the race to play a dominant role in geo-politics. The vast expanses of largely undeveloped North America and the fertile soils in many regions of this new land, opened up virtually endless potential for agricultural profits and mineral extraction. Concurrently, improvements in navigation, such as the invention of the sextant in the early 1700s, made sailing across the Atlantic Ocean safer and more efficient.

Intercontinental trade became more organized with the creation of joint stock companies, corporate businesses with shareholders whose mission was to settle and develop lands in North America. The most famous ones were the British East India Company, the Dutch East India Company, and, later, the Virginia Company which settled Jamestown.

Increased trade and development in the New World also led to increased conflict and prejudice. Europeans now debated how Native Americans should be treated. Spanish and Portuguese thinkers, such as Juan de Sepúlveda and Bartolomé de Las Casas, proposed wildly different approaches to the treatment of Native populations, ranging from peace and tolerance to dominance and enslavement. The belief in European superiority was nearly universal.

Some American Indians resisted European influence, while others accepted it. Intermarriage was common between Spanish and French settlers and the natives in their colonized territories (though rare among English and Dutch settlers). Many Indians converted to Christianity. Spain was particularly successful in converting much of Meso-America to Catholicism through the Spanish mission system. Explorers, such as Juan de Oñate, swept through the American Southwest, determined to create Christian converts by any means necessary—including violence.

As colonization spread, the use of African slaves purchased from African traders from their home continent became more common. Much of the Caribbean and Brazil became permanent settlements for plantations and their slaves. Africans adapted to their new environment by blending the language and religion of their masters with the preserved traditions of their ancestors. Religions such as voodoo are a blend of Christianity and tribal animism. Slaves sang African songs in the fields as they worked and created art reminiscent of their homeland. Some, such as the Maroon people, even managed to escape slavery and form cultural enclaves. Slave uprisings were not uncommon, most notably the Haitian Revolution.

The English Arrive

Unlike other European colonizers, the English sent large numbers of men and women to the agriculturally fertile areas of the East. Despite our vision of the perfect Thanksgiving table, relationships with local Indians were strained, at best. English intermarriage with Indians and Africans was rare, so no new ethnic groups emerged, and social classes remained rigid and hierarchical.

England’s first attempt to settle North America came a year prior to its victory over Spain, in 1587, when Sir Walter Raleigh sponsored a settlement on Roanoke Island (now part of North Carolina). By 1590 the colony had disappeared, which is why it came to be known as the Lost Colony. The English did not try again until 1607, when they settled Jamestown. Jamestown was funded by a joint-stock company, a group of investors who bought the right to establish New World plantations from the king. (How the monarchy came to sell the rights to land that it clearly did not own is just the kind of interesting question that this review will not be covering. Sorry, but it is not on the AP Exam!) The company was called the Virginia Company—named for Elizabeth I, known as the Virgin Queen—from which the area around Jamestown took its name. The settlers, many of them English gentlemen, were ill-suited to the many adjustments life in the New World required of them, and they were much more interested in searching for gold than in planting crops. (The only “gold” to be found in Virginia was iron pyrite, aka “fool’s gold,” which the ignorant aristocrats blithely gathered up.) Within three months more than half the original settlers were dead of starvation or disease, and Jamestown survived only because ships kept arriving from England with new colonists. Captain John Smith decreed that “he who will not work shall not eat,” and things improved for a time, but after Smith was injured in a gunpowder explosion and sailed back to England, the Indians of the Powhatan Confederacy stopped supplying Jamestown with food. Things got so bad during the winter of 1609–1610 that it became known as “the starving time”: nearly 90 percent of Jamestown’s 500 residents perished, with some resorting to cannibalism. The survivors actually abandoned the colony, but before they could get more than a few miles downriver, they ran into an English ship containing supplies and new settlers.

One of the survivors, John Rolfe, was notable in two ways. First, he married Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas, briefly easing the tension between the natives and the English settlers. Second, he pioneered the practice of growing tobacco, which had long been cultivated by Native Americans, as a cash crop to be exported back to England. The English public was soon hooked, so to speak, and the success of tobacco considerably brightened the prospects for English settlement in Virginia.

Because the crop requires vast acreage and depletes the soil (and so requires farmers to constantly seek new fields), the prominent role of tobacco in Virginia’s economy resulted in rapid expansion. The introduction of tobacco would also lead to the development of plantation slavery. As new settlements sprang up around Jamestown, the entire area came to be known as the Chesapeake (named after the bay). That area today comprises Virginia and Maryland.

Many who migrated to the Chesapeake did so for financial reasons. Overpopulation in England had led to widespread famine, disease, and poverty. Chances for improving one’s lot during these years were minimal. Thus, many were attracted to the New World by the opportunity provided by indentured servitude. In return for free passage, indentured servants typically promised seven years’ labor, after which they would receive their freedom. Throughout much of the seventeenth century, indentured servants also received a small piece of property with their freedom, thus enabling them (1) to survive and (2) to vote. As in Europe, the right to vote was tied to the ownership of property, and indentured servitude in America opened a path to land ownership that was not available to most working class men in populous Europe. However, indenture was extremely difficult, and nearly half of all indentured servants—most of whom were young, reasonably healthy men—did not survive their term of service. Still, indenture was common. More than 75 percent of the 130,000 Englishmen who migrated to the Chesapeake during the seventeenth century were indentured servants.

In 1618 the Virginia Company introduced the headright system as a means of attracting new settlers to the region and to address the labor shortage created by the emergence of tobacco farming, which required a large number of workers. A “headright” was a tract of land, usually about fifty acres, that was granted to colonists and potential settlers.

In 1619 Virginia established the House of Burgesses, in which any property-holding, white male could vote. All decisions made by the House of Burgesses, however, had to be approved by the Virginia Company. That year also marks the introduction of slavery to the English colonies. (See the section later in this chapter, Slavery in the Early Colonies.)

French Colonization of North America

At first glance, the French colonization of North America appears to have much in common with Spanish and English colonization. While the English had founded a permanent settlement at Jamestown in 1607, the French colonized what is today Quebec City in 1608. Like the Spanish missionaries, the French Jesuit priests were trying to convert native peoples to Roman Catholicism, but they were much more likely to spread diseases, such as smallpox, than to convert large numbers to Christianity. Like colonists from other European countries, the French were exploring as much land as they could, hoping to find natural resources, such as gold, as well as a shortcut to Asia.

Unlike the Spanish and English, however, the French colonists had a much lighter impact on the native peoples. Few French settlers came to North America, and those who did tended to be single men, some of whom intermarried with women native to the area. They also tended to stay on the move, especially if they were coureurs du bois (“runners in the woods”) who helped trade for the furs that became the rage in Europe. True, the French ultimately did play a significant role in the French and Indian War (surprise!) from 1754–1763; however, their chances of shaping the region soon known as British North America were slim from the outset and faded dramatically with the Edict of Nantes in 1598.

The four main colonizing powers in North America interacted with the native inhabitants very differently:

• Spain tended to conquer and enslave the native inhabitants of the regions it colonized. The Spanish also made great efforts to convert Native Americans to Catholicism. Spanish colonists were overwhelmingly male, and many had children with native women, leading to settlements populated largely by mestizos, people of mixed Spanish and Native American ancestry.

• France had significantly friendlier relations with indigenous tribes, tending to ally with them and adopt native practices. The French had little choice in this: French settlements were so sparsely populated that taking on the natives head-on would have been very risky.

• The Netherlands attempted to build a great trading empire, and while it achieved great success elsewhere in the world, its settlements on the North American continent, which were essentially glorified trading posts, soon fell to the English. This doesn’t mean they were unimportant: One of the Dutch settlements was New Amsterdam, later renamed New York City.

• England differed significantly from the three other powers in that the other three all depended on Native Americans in different ways: as slave labor, as allies, or as trading partners. English colonies, by contrast, attempted to exclude Native Americans as much as possible. The English flooded to the New World in great numbers, with entire families arriving in many of the colonies rather than just young men, and intermixing between settlers and natives was rare. Instead, when English colonies grew to the point that conflict with nearby tribes became inevitable, the English launched wars of extermination. For instance, the Powhatan Confederacy was destroyed by English “Indian fighters” in the 1640s.

The Pilgrims and the Massachusetts Bay Company

During the sixteenth century, English Calvinists led a Protestant movement called Puritanism in England. Its name was derived from its adherents’ desire to purify the Anglican church of Roman Catholic practices. English monarchs of the early seventeenth century persecuted the Puritans, and so the Puritans began to look for a new place to practice their faith.

One Puritan group, called Separatists—because they thought the Church of England was so incapable of being reformed that they had to abandon it—left England around this time. First they went to the Netherlands but ultimately decided to start fresh in the New World. In 1620 they set sail for Virginia, but their ship, the Mayflower, went off course and they landed in modern-day Massachusetts. Because winter was approaching, they decided to settle where they had landed. This settlement was called Plymouth.

While on board, the travelers—called “Pilgrims” and led by William Bradford—signed an agreement establishing a “body politic” and a basic legal system for the colony. That agreement, the Mayflower Compact, is important not only because it created a legal authority and an assembly, but also because it asserted that the government’s power derives from the consent of the governed and not from God, as some monarchists known as Absolutists believed.

Like the earlier settlers in Jamestown, the Pilgrims received life-saving assistance from local Native Americans. To the Pilgrims’ great fortune, they had happened to land at the site of a Patuxet village that had been wiped out by disease; one inhabitant of that village, a man named Tisquantum, better known as Squanto, had been spared this fate because he had been captured years before and brought to Europe as a slave. He wound up in London, where he learned English and then returned to his homeland only to find it depopulated. Shortly thereafter, the Pilgrims arrived, and Squanto became their interpreter and taught them how best to plant in their new home.

In 1629 a larger and more powerful colony called Massachusetts Bay was established by Congregationalists (Puritans who wanted to reform the Anglican church from within). This began what is known as The Great Puritan Migration, which lasted from 1629 to 1642. Led by Governor John Winthrop, Massachusetts Bay developed along Puritan ideals. While onboard the ship Arabella, Winthrop delivered a now-famous sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity,” urging the colonists to be a “city upon a hill”—a model for others to look up to. All Puritans believed they had a covenant with God, and the concept of covenants was central to their entire philosophy, in both political and religious terms. Government was to be a covenant among the people; work was to serve a communal ideal, and, of course, the Puritan church was always to be served. This is why both the Separatists and the Congregationalists did not tolerate religious freedom in their colonies, even though both had experienced and fled religious persecution.

The settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were strict Calvinists, and Calvinist principles dictated their daily lives. For example, much has been written about the “Protestant work ethic” and its relationship to the eventual development of a market economy. In fact, some historians believe the roots of the Civil War can be traced back to the founding of the Chesapeake region and New England, as a plantation economy dependent on slave labor developed in the Chesapeake and subsequent southern colonies, while New England became the commercial center.

Two major incidents during the first half of the seventeenth century demonstrated Puritan religious intolerance. Roger Williams, a minister in the Salem Bay settlement, taught a number of controversial principles, among them that church and state should be separate. The Puritans banished Williams, who subsequently moved to modern-day Rhode Island and founded a new colony. Rhode Island’s charter allowed for the free exercise of religion, and it did not require voters to be church members. Anne Hutchinson was a prominent proponent of antinomianism, the belief that faith and God’s grace—as opposed to the observance of moral law and performance of good deeds—suffice to earn one a place among the “elect.” Her teachings challenged Puritan beliefs and the authority of the Puritan clergy. The fact that she was an intelligent, well-educated, and powerful woman in a resolutely patriarchal society turned many against her. She was tried for heresy, convicted, and banished.

Puritan immigration to New England came to a near halt between 1649 and 1660, the years during which Oliver Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector of England. Cromwell’s reign represented the culmination of the English Civil Wars, which the Puritans won. During the Interregnum (literally “between kings”), Puritans had little motive to move to the New World. Everything they wanted—freedom to practice their religion, as well as representation in the government—was available to them in England. With the restoration of the Stuarts, many English Puritans again immigrated to the New World. Not coincidentally, these immigrants brought with them some of the republican ideals of the revolution.

The lives of English settlers in New England and the Chesapeake differed considerably. Entire families tended to immigrate to New England; in the Chesapeake, immigrants were often single males. The climate in New England was more hospitable, and so New Englanders tended to live longer and have larger families than Chesapeake residents. A stronger sense of community, and the absence of tobacco as a cash crop, led New Englanders to settle in larger towns that were closer to one another; those in the Chesapeake lived in smaller, more spread-out farming communities. While both groups were religious, the New Englanders were definitely more religious, settling near meetinghouses. Another important difference between New England and the Chesapeake was in the use of slavery. New England farms were small and required less labor. Slavery was rare. Middle and Southern farms were much larger, requiring large numbers of African slaves. In fact, at one time South Carolina had a larger proportion of African slaves than European settlers.

Other Early Colonies

Several colonies were proprietorships; that is, they were owned by one person, who usually received the land as a gift from the king. Connecticut was one such colony, receiving its charter in 1635 and producing the Fundamental Orders, usually considered the first written constitution in British North America. Maryland was another, granted to Cecilius Calvert, Lord Baltimore. Calvert hoped to create a haven colony for Catholics, who faced religious persecution in Protestant England, but he also hoped to make a profit growing tobacco. In order to populate the colony’s land more quickly, Calvert offered religious tolerance for all Christians, and Protestants soon outnumbered Catholics, recreating England’s old tension between the faiths. After a Protestant uprising in England against a Catholic-sympathizing king, Maryland’s government passed the Act of Toleration in 1649 to protect the religious freedom of most Christians, but the law was not enough to keep the situation in Maryland from devolving into bloody religious civil war for much of the rest of the century.

New York was also a royal gift, this time to James, the king’s brother. The Dutch Republic was the largest commercial power during the seventeenth century and, as such, was an economic rival of the British. The Dutch had established an initial settlement in 1614 near present-day Albany, which they called New Netherland, and a fort at the mouth of the Hudson River in 1626. This fort would become New Amsterdam and is today New York City. In 1664 Charles II of England waged a war against the Dutch Republic and sent a naval force to capture New Netherland. Already weakened by previous clashes with local Native Americans, the Dutch governor, Peter Stuyvesant, along with 400 civilians, surrendered peacefully. Charles II’s brother, James, became the Duke of York, and when James became king in 1685, he proclaimed New York a royal colony. The Dutch were allowed to remain in the colony on generous terms, and they made up a large segment of New York’s population for many years. Charles II also gave New Jersey to a couple of friends, who in turn sold it off to investors, many of whom were Quakers.

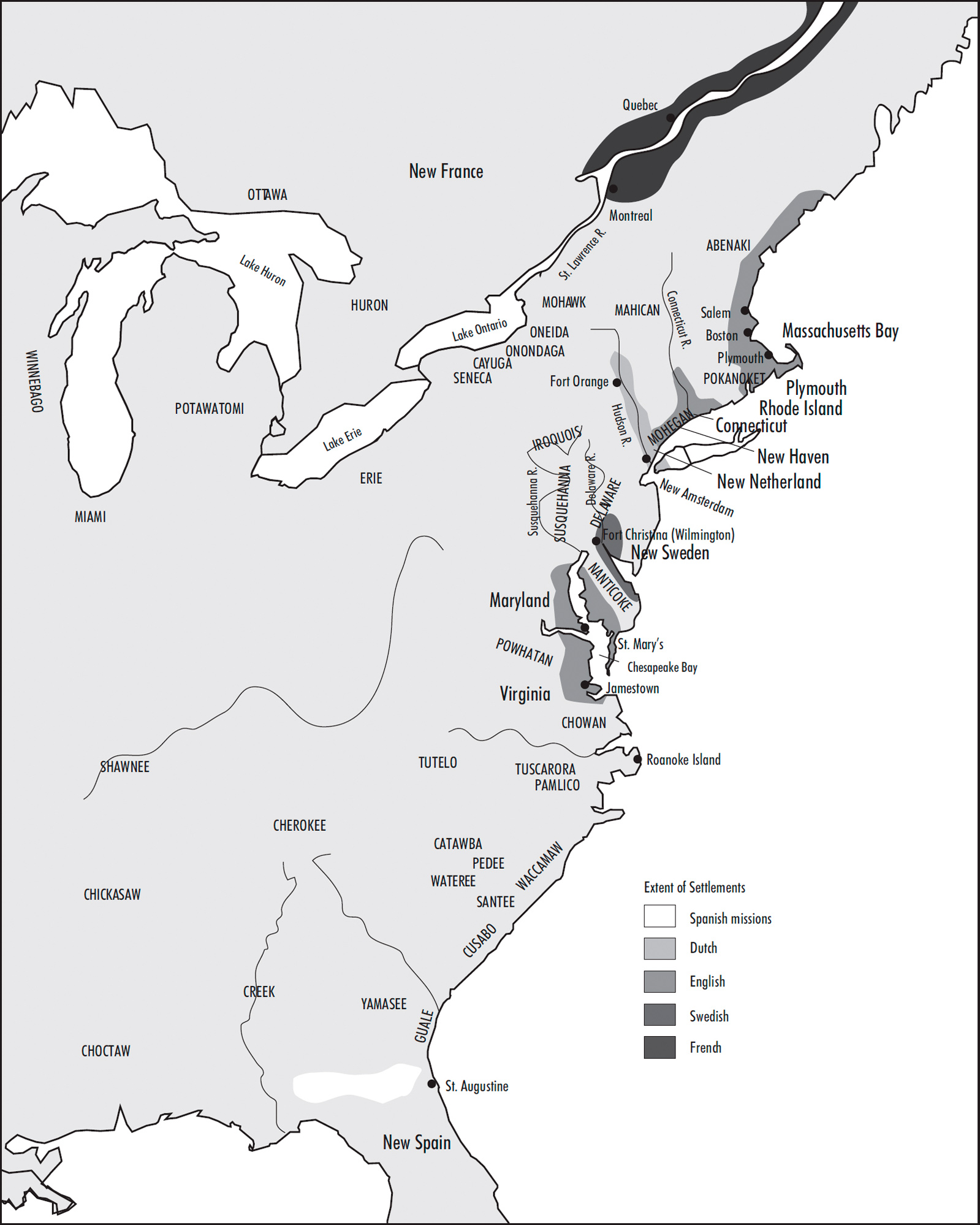

European Settlements in North America, 1650

Ultimately, the Quakers received their own colony. William Penn, a Quaker, was a close friend of King Charles II, and Charles granted Penn what became Pennsylvania. Charles, like most Anglicans, perceived the egalitarian Quakers as dangerous radicals, but the two men’s friendship (and Charles’s desire to export the Quakers to someplace far from England) prevailed. Penn established liberal policies toward religious freedom and civil liberties in his colony. That, the area’s natural bounty, and Penn’s recruitment of settlers through advertising, made Pennsylvania one of the fastest growing of the early colonies. He also attempted to treat Native Americans more fairly than did other colonies and had mixed results. His attitude attracted many tribes to the area but also attracted many European settlers who bullied tribes off of their land. An illustrative story: Penn made a treaty with the Delawares to take only as much land as could be walked by a man in three days. Penn then set off on a leisurely stroll, surveyed his land, and kept his end of the bargain. His son, however, renegotiating the treaty, hired three marathon runners for the same task, thereby claiming considerably more land.

Carolina was also a proprietary colony, but in 1729 it officially split into North Carolina, settled by Virginians as a Virginia-like colony, and South Carolina, settled by the descendants of Englishmen who had colonized Barbados. Barbados’s primary export was sugar, and its plantations were worked by slaves. Although slavery had existed in Virginia since 1619, the settlers from Barbados were the first Englishmen in the New World who had seen widespread slavery at work. Their arrival truly marked the beginning of the slave era in the colonies.

Eventually, most of the proprietary colonies were converted to royal colonies; that is, their ownership was taken over by the king, who could then exert greater control over their governments. By the time of the Revolution, only Connecticut, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, and Maryland were not royal colonies.

For an overview of which areas were settled by whom during this period, see the map on the previous page.

Conflicts with American Indians

Here are some important conflicts between colonists and American Indians that you should know:

The Pequot War (1636–1638): As the population of Massachusetts grew, settlers began looking for new places to live. One obvious choice was the Connecticut Valley, a fertile region with lots of access to the sea (for trade). The area was already inhabited by the Pequots, however, who resisted the English incursions. When the Pequots attacked a settlement in Wakefield and killed nine colonists, members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony retaliated by burning the main Pequot village, killing 400, many of them women and children. The result was the near-destruction of the Pequots in what came to be known as the Pequot War.

Decline of the Huron Confederacy (1634–1649): At one time the Hurons numbered up to 40,000, living primarily near Lake Ontario and in parts of Quebec, but with some groups as far south as West Virginia. During the 1630s, though, smallpox ravaged the tribes, and their numbers declined to around 12,000. Added to their woes were constant conflicts with other tribes for fur rights. The Huron were allies with the French and fought alongside them in the Seven Years’ War.

King Philip’s War (1675–1678): Metacomet, the leader of the Wampanoag tribe living near Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, was neither a King nor named “Philip.” The Wampanoags were surrounded by white settlements, and colonists were attempting to convert the Indians to English culture and religion. “Praying towns” were villages set up for the sole purpose of making converts to Christianity. Indians were also encouraged to give up their tribal clothing. Metacomet led attacks on several settlements in retaliation for this intrusion on Wampanoag territory. Soon after, he formed an alliance with two other local tribes. The alliance destroyed a number of English settlements but eventually ran out of food and ammunition. When Metacomet died, the alliance fell apart and the colonists devastated the tribes, selling many into slavery in the West Indies. King Philip’s War marks the end of a formidable Native American presence among the New England colonists.

The Pueblo Revolt (1680): While the French and British played their political and economic chess games with Indian tribes in the East, the Spanish sought to maintain control of the Southwest. After years of domination by the fearsome Juan de Onate, the Pueblo people of New Mexico led a successful revolt against the Spanish, killing hundreds and driving the remaining settlers out of the region. The Spanish returned in 1692, and, though they regained control of the territory, they were more accommodating to the Pueblo, the fear of continued conflicts driving the need for compromise.

Slavery in the Early Colonies

As mentioned above, the extensive use of African slaves in the American colonies began when colonists from the Caribbean settled the Carolinas. Until then, indentured servants and, in some situations, enslaved Native Americans had mostly satisfied labor requirements in the colonies. As tobacco-growing and, in South Carolina, rice-growing operations expanded, more laborers were needed than indenture could provide. Events such as Bacon’s Rebellion (see Major Events of the Period for more on this) had also shown landowners that it was not in their best interest to have an abundance of landless, young, white males in their colonies either.

Enslaving Native Americans was difficult; they knew the land, so they could easily escape and subsequently were difficult to find. In some Native American tribes, cultivation was considered women’s work, so gender was another obstacle to enslaving the natives. And as noted, Europeans brought diseases that often decimated the Native Americans, wiping out 85 to 95 percent of the native population. Southern landowners turned increasingly to African slaves for labor. Unlike Native Americans, African slaves did not know the land, so they were less likely to escape. Removed from their homelands and communities, and often unable to communicate with one another because they were from different regions of Africa, black slaves initially proved easier to control than Native Americans. The dark skin of the West Africans who made up the bulk of the enslaved population made it easier to identify slaves on sight, and the English colonists came to associate dark skin with inferiority, rationalizing Africans’ enslavement.

The majority of the slave trade, right up to the Revolution, was directed toward the Caribbean and South America. Still, during that period more than 500,000 slaves were brought to the English colonies (of the over 10 million brought to the New World). By 1790 nearly 750,000 blacks were enslaved in England’s North American colonies.

The shipping route that brought the slaves to the Americas was called the Middle Passage because it was the middle leg of the triangular trade route among the colonies, Europe, and Africa. Conditions for the Africans aboard were brutally inhumane, so intolerable that some committed suicide by throwing themselves overboard. Many died of sickness, and others died during insurrections. It was not unusual for one-fifth of the Africans to die on board. Most, however, reached the New World, where conditions were only slightly better. Mounting criticism (primarily in the North) of the horrors of the Middle Passage led Congress to end American participation in the Atlantic slave trade on January 1, 1808. Slavery itself would not end in the United States until 1865.

Slavery flourished in the South. Because of the nature of the land and the short growing season, the Chesapeake and the Carolinas farmed labor-intensive crops such as tobacco, rice, and indigo, and plantation owners there bought slaves for this arduous work. Slaves’ treatment at the hands of their owners was often vicious and at times sadistic. While slavery never really took hold in the North the same way it did in the South, slaves were used on farms in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, in shipping operations in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and as domestic servants in urban households, particularly in New York City. Although northern states would take steps to phase out slavery following the Revolution, there were still slaves in New Jersey at the outbreak of the Civil War. In both regions, only the very wealthy owned slaves. The vast majority of people remained at a subsistence level.

THE AGE OF SALUTARY NEGLECT (1650–1750)

British treatment of the colonies during the period preceding the French and Indian War (also called the Seven Years’ War) is often described as “salutary neglect” or “benign neglect.” Although England regulated trade and government in its colonies, it interfered in colonial affairs as little as possible. Because of the distance, England set up absentee customs officials and the colonies were left to self-govern, for the most part. England occasionally turned its back to the colonies’ violations of trade restrictions. Thus, the colonies developed a large degree of autonomy, which helped fuel revolutionary sentiments when the monarchy later attempted to gain greater control of the New World.

During this century, the colonies “grew up,” developing fledgling economies. The beginnings of an American culture—as opposed to a transplanted English culture—took root.

English Regulation of Colonial Trade

Throughout the colonial period, most Europeans who thought about economics at all subscribed to a theory called mercantilism. Mercantilists believed that economic power was rooted in a favorable balance of trade (that is, exporting more than you import) and the control of specie (hard currency, such as gold coins). Colonies, they felt, were important mostly for economic reasons, which explains why the British considered their colonies in the West Indies that produced sugar and other valuable commodities to be more important than their colonies on the North American continent. The colonies on the North American continent were seen primarily as markets for British and West Indian goods, although they also were valued as sources of raw materials that would otherwise have to be bought from a foreign country.

In order to guarantee a favorable balance of trade, the British government encouraged manufacturing in England and placed protective tariffs on imports that might compete with English goods. A number of such tariffs, included in the Navigation Acts, were passed between 1651 and 1673. The Navigation Acts required the colonists to buy goods only from England, to sell certain of their products only to England, and to import any non-English goods via English ports and pay a duty on those imports. The Navigation Acts also prohibited the colonies from manufacturing a number of goods that England already produced. In short, the Navigation Acts sought to establish wide-ranging English control over colonial commerce. Also of note was the Wool Act of 1699, which forbid both the export of wool from the American colonies and the importation of wool from other British colonies. Some colonists protested this law by dealing only in flax and hemp. Likewise, the Molasses Act of 1733 imposed an exorbitant tax upon the importation of sugar from the French West Indies (thus protecting British merchants). New Englanders frequently refused to pay the tax, an early example of rebellion against the Crown.

The Navigation Acts were only somewhat successful in achieving their goal, as it was easy to smuggle goods into and out of the colonies. The colonists also did not protest aggressively against the Navigation Acts at the time, because they were entirely dependent on England for trade and for military protection.

Colonial Governments

Despite trade regulations, the colonists maintained a large degree of autonomy. Every colony had a governor who was appointed by either the king or the proprietor. Although the governor had powers similar to the king’s in England, he was also dependent on colonial legislatures for money. Also, the governor, whatever his official powers, was essentially stranded in the New World. His power relied on the cooperation of the colonists, and most governors ruled accordingly, only infrequently overruling the legislatures.

Except for Pennsylvania (which had a unicameral legislature with just one house), all the colonies had bicameral legislatures modeled after the British Parliament. The lower house functioned in much the same way as does today’s House of Representatives; its members were directly elected (by white, male property holders), and its powers included the “power of the purse” (control over government salaries and tax legislation). The upper house was made up of appointees, who served as advisors to the governor and had some legislative and judicial powers. Most of these men were chosen from the local population. Most were concerned primarily with protecting the interests of colonial landowners.

The British never tried to establish a powerful central government in the colonies. The autonomy that England allowed the colonies helped ease their transition to independence in the following century.

The colonists did make some small efforts toward centralized government. The New England Confederation was the most prominent of these attempts. Although it had no real power, it did offer advice to the northeastern colonies when disputes arose among them. It also provided colonists from different settlements the opportunity to meet and to discuss their mutual problems.

Major Events of the Period

Bacon’s Rebellion took place on Virginia’s western frontier in 1676. With virtually all coastal land having been claimed, newcomers who sought to start their own farms in the region were forced west into the back country. Encroaching on land inhabited by Native Americans made frontier farmers subject to raids. In response, the western settlers sought to band together and drive the native tribes out of the region. In this effort, they were stymied by the government in Jamestown, which did not want to risk a full-scale war. Class resentment grew as frontiersmen, many of whom had been indentured servants, began to suspect that eastern elites viewed them as expendable “human shields” serving as a buffer between them and the natives.

The farmers rallied behind Nathaniel Bacon, a recent immigrant who, despite his wealth, had arrived too late to settle on the coast. Bacon demanded that Governor William Berkeley grant him the authority to raise a militia and attack the nearby tribes. When Berkeley refused, Bacon and his men lashed out at the natives anyway, attacking not only the Susquehannock but also the Pamunkeys, who were actually allies of the English. The rebels then turned their attention to Jamestown, sacking and burning the city. The rebellion dissolved when Bacon suddenly died of dysentery, and the conflict between the colonists and Native Americans was averted with a new treaty, but Bacon’s Rebellion is often cited as an early example of a populist uprising in America.

Bacon’s Rebellion is significant for other reasons not always discussed in most textbooks. Many disgruntled former indentured servants allied themselves with free blacks who were also disenfranchised—or unable to vote. This alliance along class lines, as opposed to racial lines, frightened many Southerners and led to the development of what would eventually become black codes. Bacon’s Rebellion may also be seen as a precursor to the American Revolution. As colonists pushed westward, in search of land, but away from the commercial and political centers, they experienced a sense of alienation and desire for greater political autonomy. It is important to remember that Berkeley was the royal governor of Virginia, and the backcountry of Virginia was even farther from London.

Insurrections led by slaves did not begin until nearly 70 years later with the Stono Uprising, the first and one of the most successful slave rebellions. In September 1739, approximately 20 slaves met near the Stono River outside Charleston, South Carolina. They stole guns and ammunition, killed storekeepers and planters, and liberated a number of slaves. The rebels, now numbering about 100, fled to Florida, where they hoped the Spanish colonists would grant them their freedom. The colonial militia caught up with them and attacked, killing some and capturing most of the others. Those who were captured and returned were later executed. As a result of the Stono Uprising (sometimes called the Cato Rebellion), many colonies passed more restrictive laws to govern the behavior of slaves. Fear of slave rebellions increased, and New York experienced a “witch hunt” period, during which 31 blacks and 4 whites were executed for conspiracy to liberate slaves.

Speaking of witch hunts, the Salem Witch Trials took place in 1692. These were not the first witch trials in New England. During the first 70 years of English settlement in the region, 103 people (almost all women) had been tried on charges of witchcraft. Never before had so many been accused at once, however; during the summer of 1692, more than 130 “witches” were jailed or executed in Salem.

Historians have a number of explanations for why the mass hysteria started and ended so quickly. The region had recently endured the autocratic control of the Dominion of New England, an English government attempt to clamp down on illegal trade. In 1691 Massachusetts became a royal colony under the new monarchs, and suffrage was extended to all Protestants; previously only Puritans could vote, so this move weakened Puritan primacy. War against French and Native Americans on the Canadian border (called King William’s War in the colonies and the War of the League of Augsburg in England) soon followed and further heightened regional anxieties.

To top it all off, the Puritans feared that their religion—which they fervently believed was the only true religion—was being undermined by the growing commercialism in cities like Boston. Many second- and third-generation Puritans lacked the fervor of the original Pilgrim and Congregationalist settlers, a situation that led to the Halfway Covenant, which changed the rules governing Puritan baptisms. (Prior to the passage of the Halfway Covenant in 1662, a Puritan had to experience the gift of God’s grace in order for his or her children to be baptized by the church. With so many, particularly men, losing interest in the church, the Puritan clergy decided to baptize all children whose parents were baptized. However—here is the “halfway” part—those who had not experienced God’s grace were not allowed to vote.) All of these factors—religious, economic, and gender—historians argue, combined to create mass hysteria in Salem in 1692. The hysteria ended when the accusers, most of them teenage girls, accused some of the colony’s most prominent citizens of consorting with the Devil, thus turning town leaders against them. Some historians also feel that the hysteria had simply run its course.

As noted, the generations that followed the original settlers were generally less religious than those that preceded them. By 1700 women constituted the majority of active church members. However, between the 1730s and 1740s the colonies (and Europe) experienced a wave of religious revivalism known as the Great Awakening. Two men, Congregationalist minister Jonathan Edwards and Methodist preacher George Whitefield, came to exemplify the period. Edwards preached the severe, predeterministic doctrines of Calvinism and became famous for his graphic depictions of Hell; you may have read his speech “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Whitefield preached a Christianity based on emotionalism and spirituality, which today is most clearly manifested in Southern evangelism. The First Great Awakening is often described as the response of devout people to the Enlightenment, a European intellectual movement that borrowed heavily from ancient philosophy and emphasized rationalism over emotionalism or spirituality.

Whitefield was a native of England, where the Enlightenment was in full swing; its effects were also being felt in the colonies, especially in the cities. The colonist who came to typify Enlightenment ideals in America was the self-made and self-educated man, Ben Franklin. Franklin was a printer’s apprentice who, through his own ingenuity and hard work, became a wealthy printer and a successful and respected intellectual. His Poor Richard’s Almanack was extremely popular and remains influential to this day. (It is the source of such pithy aphorisms as “A stitch in time saves nine” and “A penny saved is a penny earned.”) Franklin did pioneering work in the field of electricity. He invented bifocals, the lightning rod, and the Franklin stove, and he founded the colonies’ first fire department, post office, and public library. Franklin espoused Enlightenment ideals about education, government, and religion and was, until Washington came along, the colonists’ favorite son. Toward the end of his life, he served as an ambassador in Europe, where he negotiated a crucial alliance with the French and, later, the peace treaty that ended the Revolutionary War.

Life in the Colonies

Perhaps the most important development in the colonies during this period was the rate of growth. The population in 1700 was 250,000; by 1750, that number was 1,250,000. Throughout these years the colonies began to develop substantial non-English European populations. Scotch-Irish, Scots, and Germans all started arriving in large numbers during the eighteenth century. English settlers, of course, continued to come to the New World as well. The black population in 1750 was more than 200,000, and in a few colonies (South Carolina, for example) they would outnumber whites by the time of the Revolution.

The vast majority of colonists—over 90 percent—lived in rural areas. Life for whites in the countryside was rugged but tolerable. Labor was divided along gender lines, with men doing the outdoor work such as farming, and women doing the indoor work of housekeeping and childrearing. Opportunities for social interaction outside the family were limited to shopping days and rare special community events. Both children and women were completely subordinate to men, particularly to the head of the household, in this patriarchal society. Children’s education was secondary to their work schedules. Women were not allowed to vote, draft a will, or testify in court.

Blacks, most of whom were slaves, lived predominantly in the countryside and in the South. Their lives varied from region to region, with conditions being most difficult in the South, where the labor was difficult and the climate less hospitable to hard work. Those slaves who worked on large plantations and developed specialized skills, such as carpentry or cooking, fared better than did field hands. In all cases, though, the condition of servitude was demeaning. Slaves often developed extended kinship ties and strong communal bonds to cope with the misery of servitude and the possibility that their nuclear families might be separated by sale. In the North, where black populations were relatively small, blacks often had trouble maintaining a sense of community and history.

Conditions in the cities were often much worse than those in the country. Because work could often be found there, most immigrants settled in the cities. The work they found generally paid too little, and poverty was widespread. Sanitary conditions were primitive, and epidemics such as smallpox were common. On the positive side, cities offered residents much wider contact with other people and with the outside world. Cities served as centers for progress and education.

Citizens with anything above a rudimentary level of education were rare, and nearly all colleges established during this period served primarily to train ministers.

The lives of colonists in the various regions differed considerably. New England society centered on trade. Boston was the colonies’ major port city. The population farmed for subsistence, not for trade, and mostly subscribed to rigid Puritanism. The middle colonies—New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey—had more fertile land and so focused primarily on farming (they were also known as the “bread colonies,” due to their heavy exports of grain). Philadelphia and New York City, like Boston, were major trade centers. The population of the region was more heterogeneous than was that of New England. The lower South (the Carolinas) concentrated on cash crops, such as tobacco and rice. Slavery played a major role on plantations, although the majority of Southerners were subsistence farmers who had no slaves. Blacks constituted up to half the population of some Southern colonies. The colonies on the Chesapeake (Maryland and Virginia) combined features of the middle colonies and the lower South. Slavery and tobacco played a larger role in the Chesapeake than in the middle colonies, but like the middle colonies, the Chesapeake residents also farmed grain and thus diversified their economies. The development of major cities in the Chesapeake region also distinguished it from the lower South, which was almost entirely rural.

Thus, the colonies were hardly a unified whole as they approached the events that led them to rebel. How then did they join together and defeat the most powerful nation in the world? The answer to this and other exciting questions awaits you in the next chapter.

Summary

Here are the most important concepts to remember from the Early Contact period.

○ Native populations in North America were not monolithic; they were diverse. Tribal groups varied widely in their economies, level of civilization, and interaction with each other and Europeans.

○ The Columbian exchange revolutionized both European and Native cultures by expanding trade and technology and creating a racially mixed New World, stratified by wealth and status.

○ African slavery started in this period, gradually replacing Native slavery and European indentured servitude.

○ The belief in European superiority was a key rationale for the colonization of North America

Here are the most important concepts to remember from the Colonization period.

○ Europeans and Native Americans vied for control of land, fur, and fishing rights.

○ The Spanish, French, Dutch, and British had different styles of interacting with Native populations.

Chapter 6 Review Questions

See Chapter 14 for answers and explanations.

1. Which of the following statements about indentured servitude is true?

(A) Indentured servitude was the means by which most Africans came to the New World.

(B) Indentured servitude never attracted many people because its terms were too harsh.

(C) Approximately half of all indentured servants died before earning their freedom.

(D) Indenture was one of several systems used to distinguish house slaves from field slaves.

2. The Mayflower Compact foreshadows the U.S. Constitution in which of the following ways?

(A) It posits the source of government power in the people rather than in God.

(B) It ensures both the right to free speech and the separation of church and state.

(C) It limits the term of office for all government officials.

(D) It establishes three branches of government in order to create a system of checks and balances.

3. The first important cash crop in the American colonies was

(A) cotton

(B) corn

(C) tea

(D) tobacco

4. The philosophy of mercantilism holds that economic power resides primarily in

(A) surplus manpower and control over raw materials

(B) control of hard currency and a positive trade balance

(C) the ability to extend and receive credit at favorable interest rates

(D) domination of the slave trade and control of the shipping lanes

5. Colonial vice-admiralty courts were created to enforce

(A) Puritan religious edicts

(B) prohibitions on anti-monarchist speech

(C) import and export restrictions

(D) travel bans imposed on Native Americans

6. All of the following are examples of conflicts between colonists and Native American tribes EXCEPT

(A) Bacon’s Rebellion

(B) the Pequot War

(C) the Stono Uprising

(D) King Philip’s War

7. Which of the following statements about cities during the colonial era is NOT true?

(A) Poor sanitation left colonial cities vulnerable to epidemics.

(B) Religious and ethnic diversity was greater in colonial cities than in the colonial countryside.

(C) Most large colonial cities grew around a port.

(D) The majority of colonists lived in urban areas.

8. Colleges and universities during the colonial period were dedicated primarily to the training of

(A) medical doctors

(B) scientists

(C) political leaders

(D) the clergy

9. Which of the following is the best explanation for why the British did not establish a powerful central government in the American colonies?

(A) The British cared little how the colonists lived so long as the colonies remained a productive economic asset.

(B) Britain feared that the colonists would rebel against any substantial government force that it established.

(C) Few members of the British elite were willing to travel to the colonies, even for the opportunity to govern.

(D) Britain gave the colonies a large measure of autonomy as a first step in transitioning the region to independence.

REFLECT

Respond to the following questions:

• For which content topics discussed in this chapter do you feel you have achieved sufficient mastery to answer multiple-choice questions correctly?

• For which content topics discussed in this chapter do you feel you have achieved sufficient mastery to discuss effectively in a short-answer question or an essay?

• On which content topics discussed in this chapter do you feel you need more work before you can answer multiple-choice questions correctly?

• On which content topics discussed in this chapter do you feel you need more work before you can discuss them effectively in a short-answer question or an essay?

• What parts of this chapter are you going to re-review?

• Will you seek further help, outside of this book (such as a teacher, tutor, or AP Students), on any of the content in this chapter—and, if so, on what content?