2 The early nineteenth century Girtin, Turner, Cotman, Cox, De Wint, Constable, Bonington, and the Exhibiting Societies

ALREADY, by the time of Cozens’s death in 1797, a great number of new artists were coming to the fore, who in their fertility, variety and originality were to add greatly to the lustre of the English school of watercolour painting.

The first important newcomer after J.R. Cozens is Thomas Girtin. He was born in 1775, the same year as J.M.W. Turner, and received his artistic education from Edward Dayes. The drawing of Dayes at its best is the culmination of that type of eighteenth-century drawing, of Dutch origin, in which attention is paid to the rendering of local colour and of which the keynote is neatness of architectural draughtsmanship and elegance of fashionable figure drawing. The early work of Thomas Girtin fits right into this tradition and shows how ably he imbibed his master’s instruction. It is irrelevant to the present purpose to record how Dayes is said to have quarrelled with his clever apprentice because he was jealous of his rapid mastery; how he is said to have put Girtin in prison, and after Girtin’s early death to have cast aspersions on his moral character in the short biographical notice which he wrote on him. What is relevant is that Dayes transmitted to Girtin a craftsmanship of a very high order; but it was not in the manner or idiom he learned from his master that Girtin made his original contribution to the development of watercolour drawing and fashioned his own finest drawing.

After leaving Dayes, Girtin found the customary occupation for one of his profession and accompanied an antiquary, James Moore, on a tour of the picturesque scenes and ruins of Scotland and Wales in the capacity of draughtsman. This period of his career coincides with a rather harsh transition in his style; we may call it his ‘cold’ period, for the foregrounds of drawings of this time are grey and the background blue, and the tones do not blend warmly. He was also to come under the influence of Cozens through an unofficial institution important in the history of English watercolour and known as the ‘Monro School’. Dr Monro was the doctor who attended Cozens in his mental illness, and he was a keen amateur of the English watercolourists. He had a number of drawings by Cozens, and he encouraged young artists to come to his house in the Adelphi in the evening to copy these and other drawings, for the fee of two shillings and sixpence per night. By far the most celebrated of the copyists who came to Dr Monro were Girtin and Turner. It used to be supposed that the Doctor instituted his system out of sheer benevolence to the young artists, and designed it to improve their styles. The truth seems to be, however, that he set them principally to copy drawings in the possession of other collectors simply because he wanted replicas of them for his own collection. To meet his requirements a sort of mass production was organized whereby one artist made the pencil outlines, another put in the first tint, and so on, until the copy was completed. Be that as it may, the effect of the ‘Monro School’ was to place before Girtin, and before Turner, the masterpieces of Cozens’s Italian travels, and it is only necessary to look at their maturer work to learn how they profited from this opportunity. Another source for the enrichment of Girtin’s style was his personal taste for the more spirited Italian draughtsmen of the eighteenth century. He copied architectural subjects and fantasies from Canaletto, Marco Ricci and Piranesi, and the mark of this admiration is to be found in the vitality of his line, the vivid calligraphy of his outlines, as much as in his mastery of composition.

There were two main trends in the watercolour landscape of the early English school. One branch aimed at an approximation to local colour: Girtin’s early work under the tutelage of Dayes falls into this category. The other branch of eighteenth-century English drawing follows the longer-established tradition of monochrome drawing, though no longer remaining monochrome itself. The effect of the drawing as a representation of nature is brought about in this case by the contrast of tones within a fairly restricted gamut of colours. Cozens, up till this time the greatest exemplar of the latter category, evoked the whole majesty and mass of Alpine scenery in varying tones of blue tempered with grey; he composes as it were in the key of grey-blue. Girtin in his mature style practises drawing in this same sense; and grey forms an important undertone in his colour scheme as a necessary bond between the colours he uses. But in place of the cold grey-blue of Cozens he composes in a warmer key of grey or brownish grey. The difference in tonality accurately reflects the gulf between the melancholy and unstable imagination of J.R. Cozens and the warm, sanguine temperament of young Girtin.

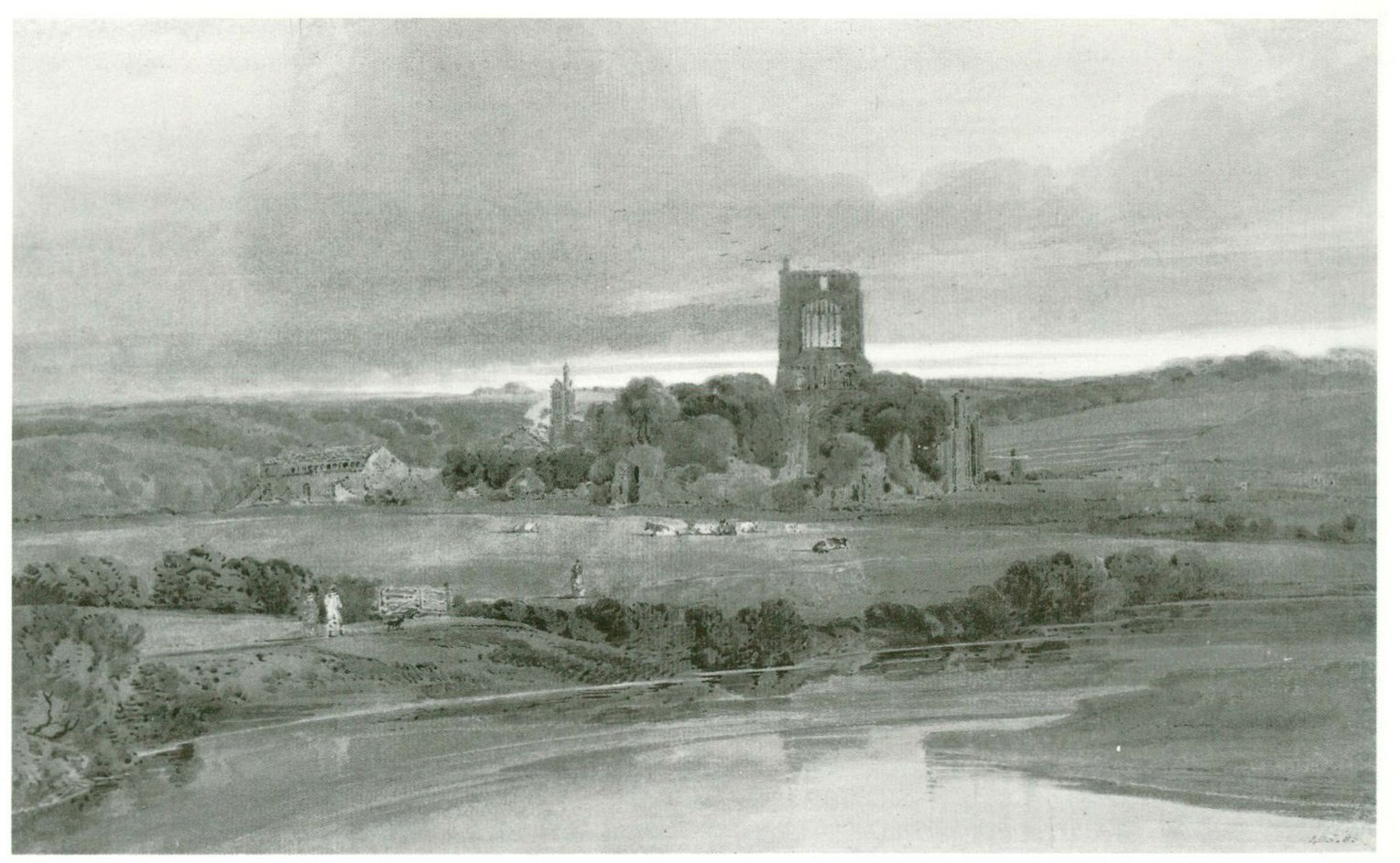

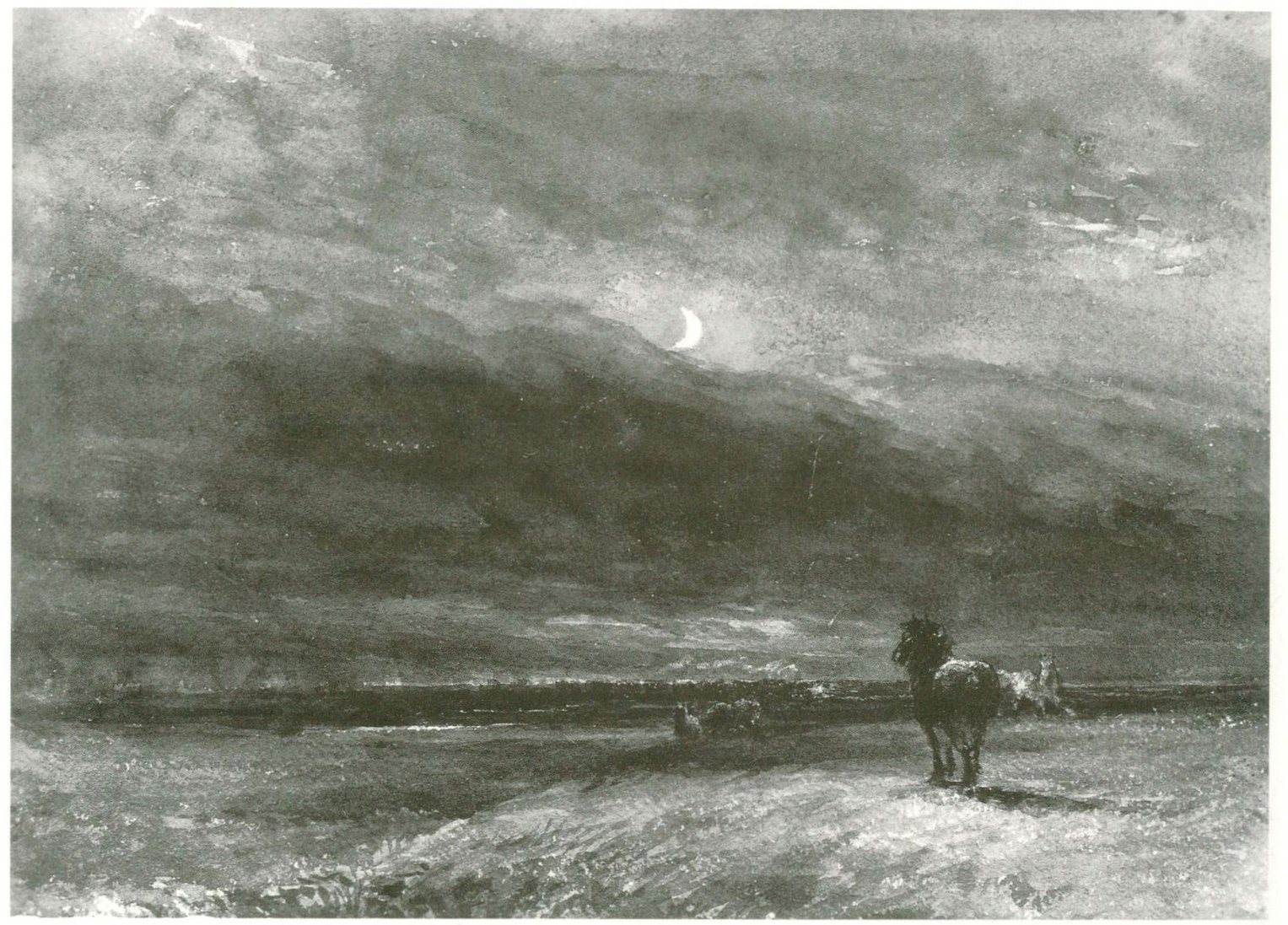

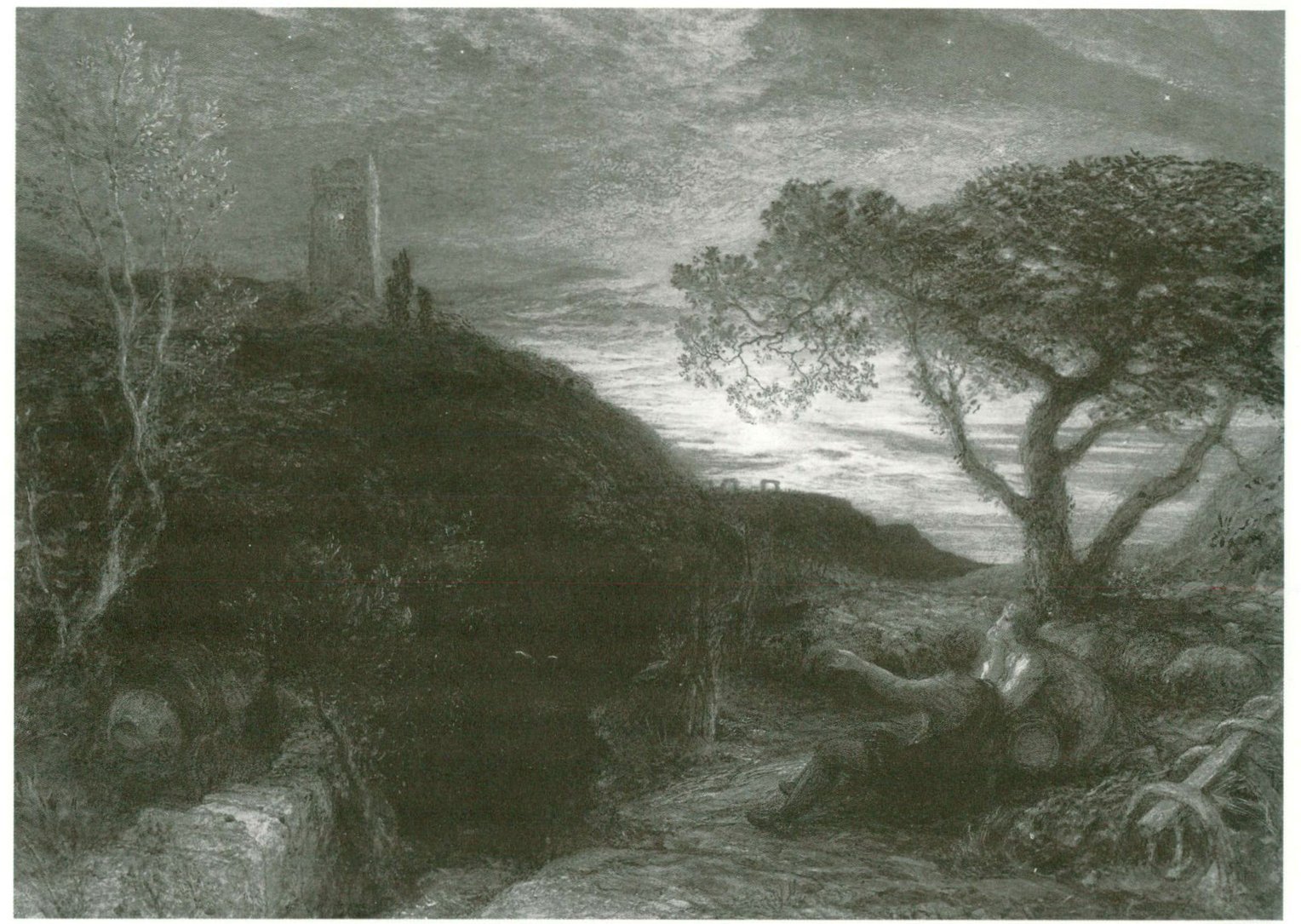

39 Thomas Girtin Kirkstall Abbey – Evening

34 Samuel Hieronymus Grimm The Macaroni

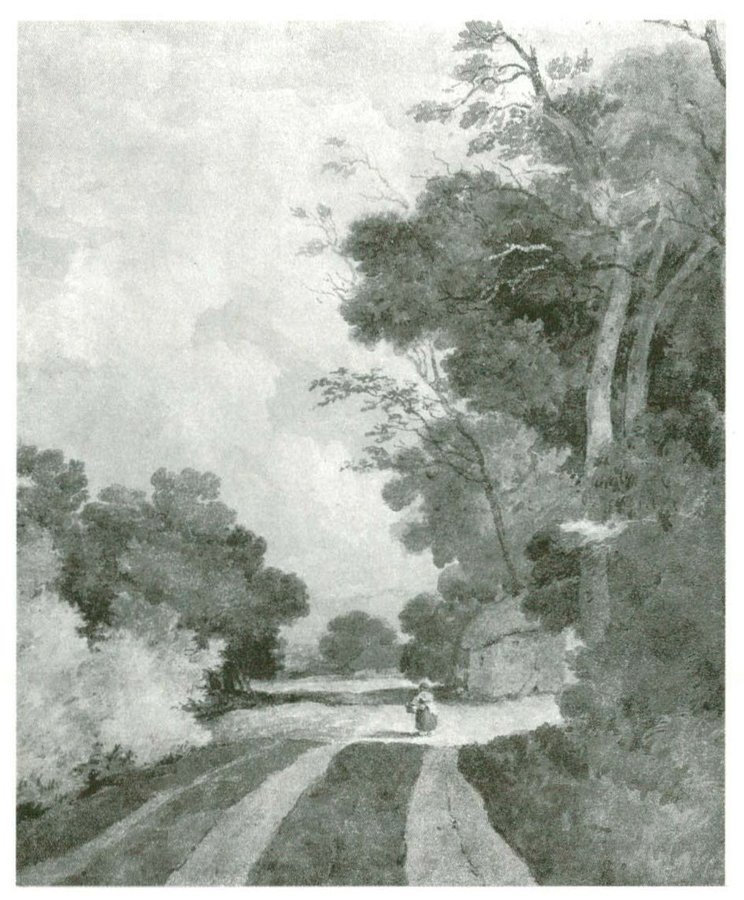

Girtin did not often draw mountainous scenery, but in his drawings of ruins he arranges the composition so that the buildings tower mountainously above the draughtsman, or, as in Kirkstall Abbey (Fig. 39), are seen with the evening light falling through the broken tracery. The details of his handling equally show his loving regard for the crumbling surface of old stone or brickwork: the brush flickers here and there, rounding off what once was square and giving the appearance of age to every nook and cranny in a wall. In less antiquarian mood he delighted to draw rolling country. Occasionally a cloud in the manner of Salvator Rosa spirals upward from a flat landscape reminiscent of Koninck. These wide expanses, typical of the countryside he loved, are diversified by few features, but are spread out beautifully by his power of composition and the interesting play of his line (Fig. 40). The same penchant for flat country is to be found in De Wint, who learned it from Girtin.

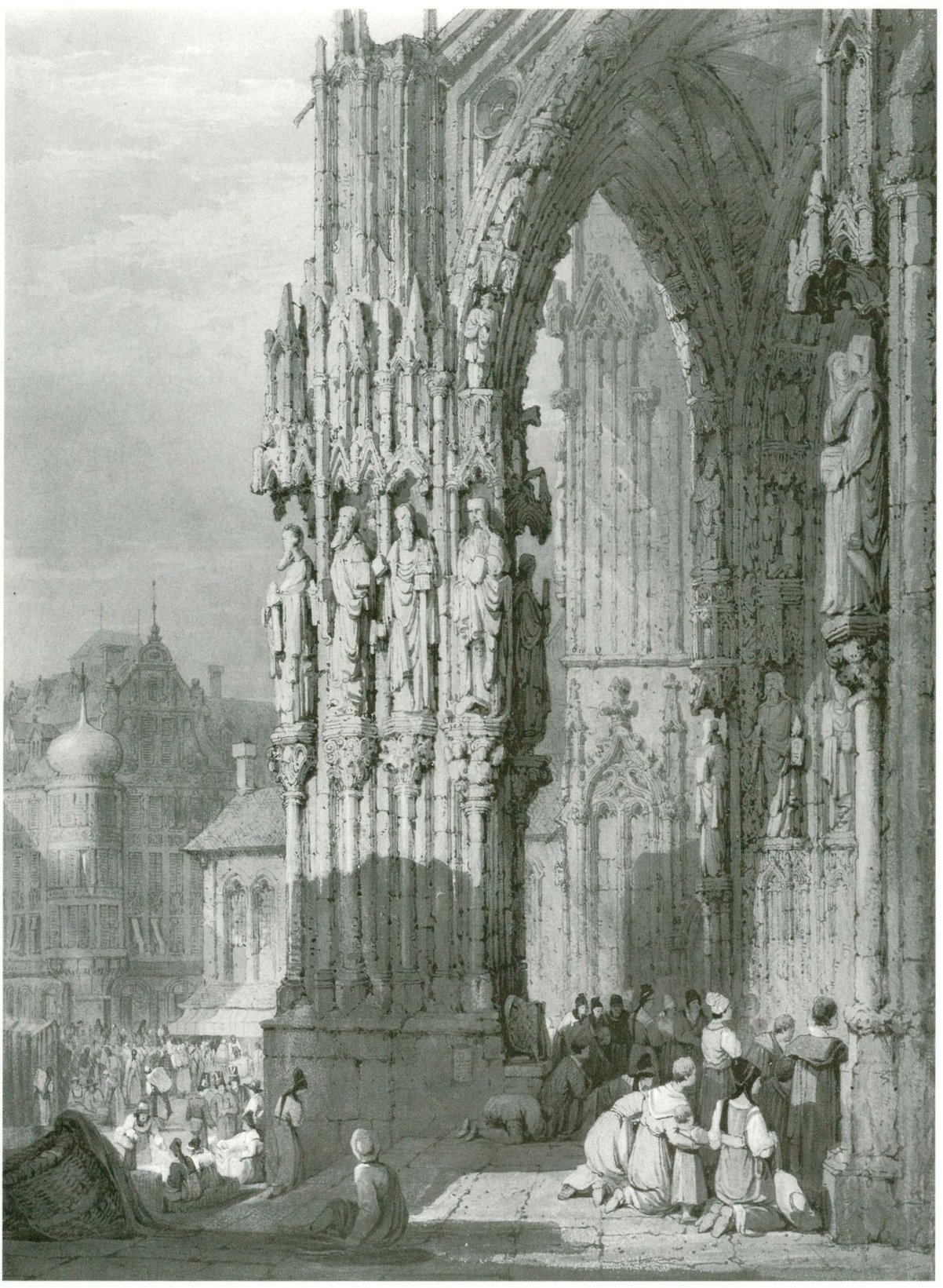

Girtin was also the first of a line of artists – Edridge, Prout, Bonington, Boys, Callow – who found a new topographical interest in drawing the streets of Paris. He went there in 1801, the year before his tragically early death at the age of twenty-seven, and in the drawings he made of the narrow streets with their vistas of buildings with regular facades is to be found the quintessence of Canaletto’s teaching to the English draughtsman and the start of a new fashion in topography. All is accurate and fully realized in form, but it is free, of vigorous line, and in no way monotonous.

To treat of Turner after Girtin is inevitable. Their courses ran side by side in the 1790s, when indeed it might at one time have seemed that Girtin had the advantage over Turner, and chance added many resemblances to a friendly rivalry which closed only with Girtin’s death in 1802. They were born in the same year and worked together in Dr Monro’s house when they were each promising young men less than twenty years old. Indeed, so closely were they linked together in the minds of their contemporaries that when Farington was making a note in his diary about their common employment by Dr Monro, he condescended to record the egregious pun that Girtin’s mother was a ‘Turner’ by trade!

As their biographies were parallel, so was the development of their style during its earliest phase: there are drawings of the period which have given plenty of scope for discussion on whether they are by the young Girtin or the young Turner. In the drawings produced for Dr Monro there is plentiful scope for confusion, particularly as Girtin is said to have made the outlines and Turner to have applied washes to them. But by 1795 or 1796 their ways diverge: each has acquired his distinct and original individuality. Turner was working somewhat in the manner of Hearne, Rooker, and Dayes; but before developing his more advanced and revolutionary styles he had raised the traditional eighteenth-century methods to new heights. The drawings of Gothic architecture which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in the 1790s are carried out in cool tones of yellowish green and greenish grey; but for all the exquisite precision of the rendering of architectural detail there is already a greatness of imaginative conception in the whole which makes them the best topographical antiquarian drawings as yet seen in the English school.

40 Thomas Girtin Hills and River

43 J.M.W. Turner Folkestone from the Sea

The comparison of similar careers is one of the most illuminating services criticism can offer, and so before Turner’s life passes beyond the possibility of such a comparison it is well to refer to some of the essential differences between him and Girtin. Both Girtin and Turner have been hailed as great originators – indeed for a long time they were regarded as the primitives of English watercolour. The ground which has already been surveyed in Chapter One shows how little basis there is for such a claim. But it is true that each artist had immense originality and struck out a new path. What is not generally recognized is that Girtin went forward by stepping backward: he reverted to the method of drawing in tone which is the characteristic of the seventeenth century, of Claude and Rembrandt. He is the last protagonist of that method in English watercolour. Turner, on the other hand, took the method of the more colour-conscious eighteenth-century watercolourists and infused it with his own growing enthusiasm for pure colour and bright light. Neither style was preferable to the other, but the difference exists and should be comprehended; especially as in regard to colour it was the lead of Turner which was followed by Cotman, Cox and the succeeding masters of English watercolour.

One other essential difference emerges from the comparison of Girtin with Turner. Turner is, early and late, obsessed with the minutest detail. As Ruskin pointed out, there is no spot of colour in his work which is not modulated. In the drawings of his earliest phase, as in the styles which succeeded to it, he leaves no broad patches of which we can say ‘the whole of that is one colour’. But he does not destroy the breadth in effect of his drawing by this concern with its parts. Girtin, on the other hand, as soon as he had emancipated himself from the tutelage of Dayes, did leave relatively immense areas of his drawing stained with one uniform wash; and when he does get down to detail he draws it calligraphically, that is, impressionistically. And in this matter of breadth of washes many later exponents of watercolour – Cotman, Varley, De Wint – found it expedient to follow Girtin, whereas those who followed Turner were able to satisfy the Victorian taste for detail.

The second phase of Turner’s watercolour style is one which is not generally so well recognized. It emerges in about the year 1800, and is characterized by a subdued harmony of colouring – yellowish brown rather than greenish grey in key – and shows in design evident marks of the study Turner was giving at this time to the works of Wilson in his efforts to master the science of composing his pictures.

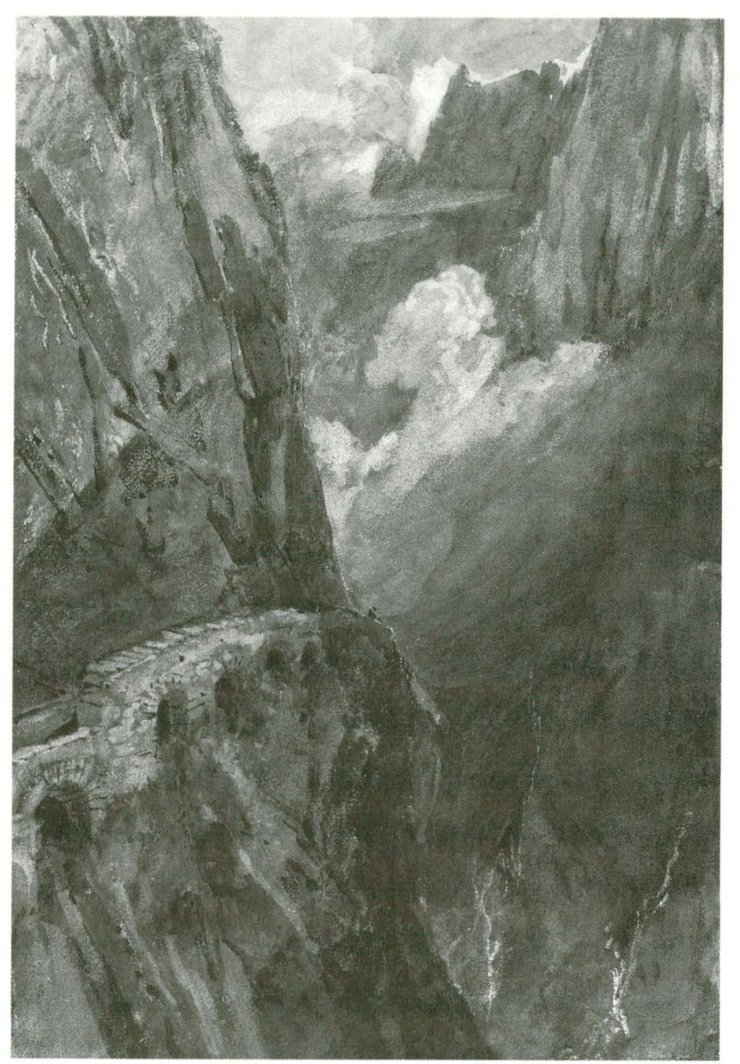

41 J.M.W. Turner The Old Road – Pass of St Gothard

Turner’s first visit to the Continent in 1802, when he travelled in France and Switzerland, stirred him profoundly. The excitement which he felt in the presence of the sublimities of Alpine scenery is expressed in his sketch of the Pass of St Gothard. The constricted vertical composition and nearly monochrome washes convey the vertiginous terror of the pass (Fig. 41).

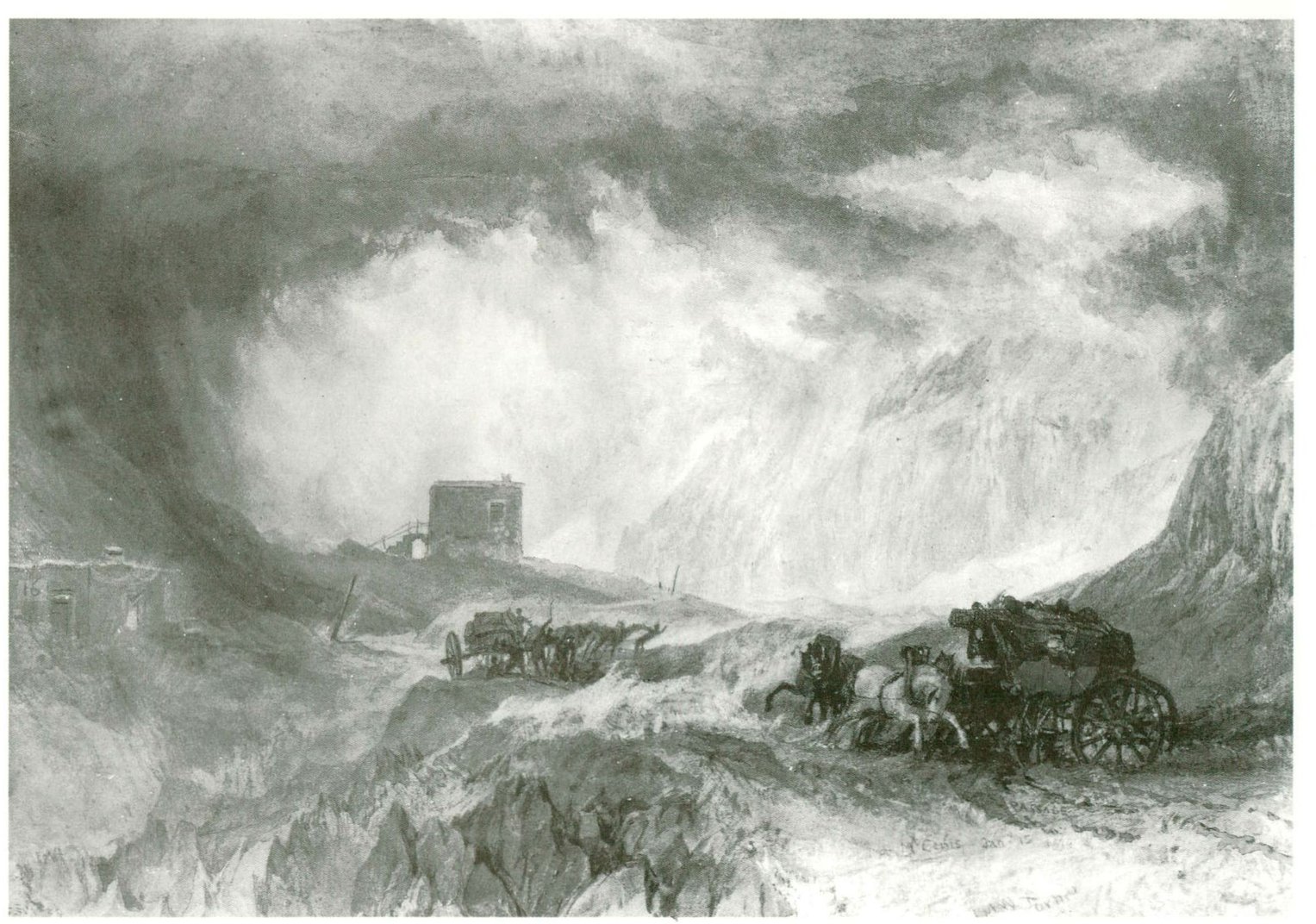

After his first visit to Italy eighteen years later, Turner set out on his return to England in January 1820. The Mont Cenis Pass was blocked by snow and the coach overturned at the summit, so that he and his party had to walk for the entire descent. He painted a record of this battle with the elements for his faithful patron, Walter Fawkes (Fig. 42).

Advancing his oil painting and watercolour drawing in tandem, Turner proceeded to abandon his earlier inhibitions about the unrestrained use of colour. In this phase of his art he produced an amazing series of jewel-like, highly finished drawings in which the blues and reds glow with intense brilliance of light. These drawings, more than any, illustrate Turner’s attention to minuteness of detail. The hillside and the sky are equally composed of a tapestry of varying colours to represent the effect of light reflected and refracted from them. Turner is obsessed with light and colour; but his instinctive memory and consciousness of form never desert him. Turner was the only member of the English watercolour school who, starting as a watercolourist, reached the highest distinction as an oil painter; in his work the two techniques interacted and each suggested developments in the other’s sphere. It was no doubt his experience with oil paint and the possibility of minute graduations in it which led Turner to discard the broad washes of traditional watercolour for stipplings and hatchings in which the white paper peers through the dots of colour and achieves the greater brilliancy.

42 J.M.W. Turner Passage of Mont Cenis: Snowstorm

44 J.M.W. Turner Burning of the Houses of Parliament

45 J.M.W. Turner Looking out to Sea, Stranded Whale

In these drawings he has left the paths of accurate or, as he thought, ‘mere’, topography for the more generalized approach. Now, when he drew Rouen or Folkestone (Fig. 43) it was not a photographically exact copy of the scene before him, but a representation true to the genius loci combining salient and recognizable features with picturesque embellishments, the vehicles of the artist’s own feeling. In addition to being a generalizer, Turner also aimed at the universal: in quest of the whole geographical truth, as it were, he made those frenzied tours down the Rhine and the Moselle, to Venice and Switzerland; he had to see everything, to make scanty sketches in the notebooks he always had in his hand, and from them to work up, by means of his amazing visual memory, and inexhaustible repertory of forms, this series of full-dress drawings. The drawings themselves were often intended for engraving, in books with such titles as Picturesque Views on the Southern Coast, Picturesque Views in England and Wales, The Rivers of France, and so on; and by his own personal supervision and instruction Turner trained a generation of engravers capable of rendering the nuance and tone of his most elaborate and subtle compositions.

Finally we come to the last phase of Turner’s style, that rightly or wrongly called ‘impressionistic’, when his love of colour almost overcame his love of form and he seems to make abstract and, at first sight, unintelligible transcripts of the visible world. At first sight, because on close inspection there is seen to be both form and meaning in what he has drawn: he has caught the scene as it might flash upon the sight on a brilliant summer day. The interiors of Petworth are amongst the best-known examples of these later series, and there is something in the method which suits it better to the rendering of the intimacy of a domestic interior than a searching inquisition with a lens of perfectly adjusted focus. From the same period also come Turner’s most resplendent views of Venice burning brightly beneath its revealing sun, and at this time too he delighted in delineating the Swiss valleys swimming in mist, with castles perched on inaccessible crags. Turner was then, as he had always been, a Romantic, and as happens with many great imaginative artists, the freedom of his Romanticism grew more unrestrained as he grew older.

The burning of the Houses of Parliament in 1834 provided him with an ideal subject. He was prone to represent scenes of disaster, and here was one happening before his own eyes. It was symbolic of the threat to the constitution, of which he had long been a prophet of doom. At the same time it was a magnificent display of red and yellow flame against a blue sky; a cosmic firework display which brought out all his skill in the watercolour sketches he made of it (Fig. 44).

In the last years of his life he read Thomas Beale’s The Natural History of the Sperm Whale and the shadowy shape of a whale is sometimes to be discerned in the almost abstract patterns of colour which constitute his latest studies of the coast (Fig. 45).

The first years of the nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of an institution which organized most of the leading watercolour painters, canalized the available patronage, and acted as a strong formative influence on the future development of the English style. This institution was the Society of Painters in Water-Colours, known, to prevent confusion with similar rival bodies which were set up later, as the ‘Old’ Water-Colour Society. It was inaugurated in 1804 by a group of watercolour painters who were dissatisfied with the treatment accorded to their wares in the Royal Academy. They complained that their watercolours were hung alongside the inferior oil paintings on crowded walls and in a bad light; further, that the title of Royal Academician, by the rules of the Academy, would not be conferred on those who painted only in watercolours. They also had faith, which proved fully justified, in the prospective profits to be made from the rich patronage of the new merchant and nabob class.

So the Old Water-Colour Society was formed and held its first exhibition in 1805, with a membership of sixteen artists. The Society was never an open society: it kept to a small, closed number of exhibitors and replaced them by invitation. Apart from a setback due to the financial stress of the Napoleonic Wars it was uniformly prosperous, and it was fairly representative of English watercolour till about 1850, when the challenge of Pre-Raphaelitism found it, like many another established academic institution, not flexible enough in its ideas to meet a change of taste.

Although, or because, they had taken such pains to segregate watercolours from oil paintings, it was from the very beginning a tenet of the Society’s that watercolours could vie with oils in depth and richness of colour and in brilliancy. Following the practice of the time, the drawings were exhibited framed, like oil paintings, with heavy gilt mouldings right up to their edges. It was not till after 1850 that the white mounts, which our modern taste prefers to set off watercolours, began to oust these heavy gilt frames from favour, and then only gradually.

In spite of the quite separable individuality of each of the members of the Old Water-Colour Society, a homogeneous style was to be discerned in its exhibitions. It was a style different in many ways from that of the eighteenth-century topographical draughtsman’s, and equally different from Cozens or Turner. In composition the hand of Gaspard Poussin, Claude and the other seventeenth-century landscape painters lay far more heavily upon the work of this group. In colour, while the artists strive after richness and complexity, they have, in their competition with oil painting, often caught its deep tonality and its varnish brown. Sir George Beaumont’s brown tree and old Cremona violin would not be out of place in the works of Glover or Barrett, Hills or Robson. The combined effect of dark tonality with formalized picturesque composition gives a certain heaviness to the productions of the early members of the Old Water-Colour Society which contrasts greatly with the lightness of Rooker, Pars and Hearne, to name but three of the predecessors whom they despised as old-fashioned makers of feebly-tinted drawings. But when due allowance has been made for the change of outlook many worthy draughtsmen are to be found in the lists of the Old Society, and the majority of enduring early nineteenth-century reputations were made possible by the encouragement and recognition afforded through the Old Water-Colour Society – for instance, those of Varley, Cox and De Wint.

46 Joshua Cristall A Girl Peeling Vegetables

50 Robert Hills A Village Snow Scene

An artist senior to these among the founders of the Old Water-Colour Society was Joshua Cristall. He was approaching forty years of age when the Society was founded, and had lived a life of great hardship pervaded by the determination to practise art at all hazards. Subsequently he became President of the Society, but his career was never a prosperous one. Cristall was an accomplished draughtsman of the human figure. His work in this field ranges from sympathetically observed countryfolk (Fig. 46) to elaborate compositions; the Fishmarket on the Beach at Hastings which he exhibited at the Old Water-Colour Society in 1808 (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) is a complex arrangement of over thirty figures in a crowded but not confused composition. Some of his subject matter ran parallel to the poetic tastes of the Sketching Society of which he was a member, and he was one of the earlier British artists to allow his imagination to wander with classical shepherds in Arcadian fields (Fig. 47). He also painted the contemporary landscape and went on sketching tours in North Wales and the Lake District.

It is said that Cristall’s wife criticized his work on the grounds that it was insufficiently finished, but that, after trying to adjust himself to her views, he returned to his former broad manner. It is his broad manner which now forms the basis of the continuing appeal of his work. Cristall is the first to bring into watercolour that squareness and concentration on the basic facts of form which is an anticipation of Cézanne and Cubism. In my opinion, we may find in him the basis and origin of Cotman’s first and greatest style. Cristall has a less attractive sense of colour and a certain heaviness; but he had a fine sense of structure and used watercolour to express it in an original and legitimate way.

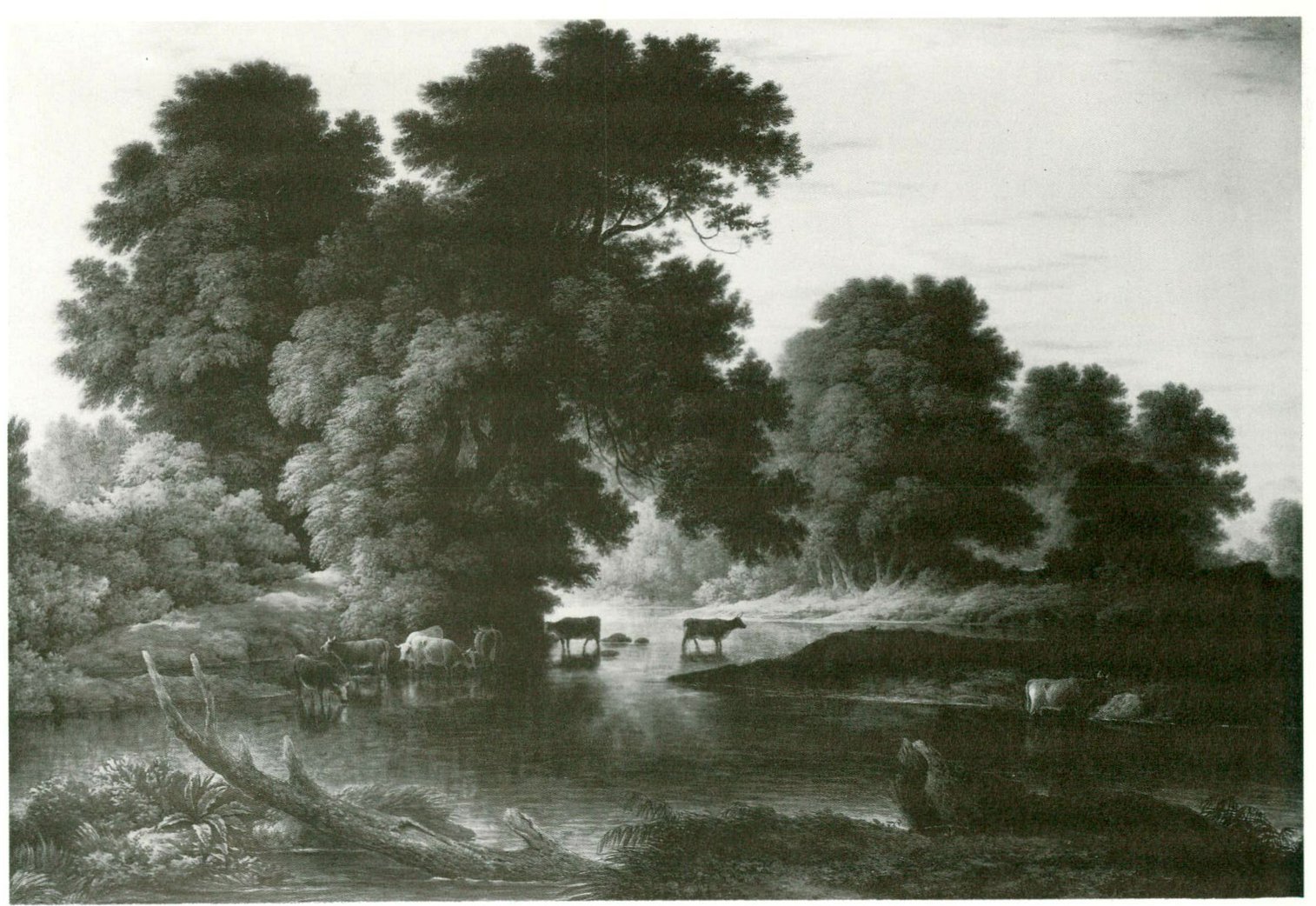

47 Joshua Cristall Arcadian Landscape with

Herdsmen by a River

John Glover, who was also a founding member of the Old Water-Colour Society, was, in contrast, very successful both as an artist and as a teacher. He was the son of a small farmer and spent his youth in the fields of Leicestershire; but his ingrained fondness for art could not be gainsaid, and he graduated from the post of writing-master in a free school to become a teacher and artist on his own account. Glover developed ambitions as an oil painter, and in his compositions in that medium we can read clearly enough his desire to emulate Claude and Gaspard Poussin. He had paintings by Claude in his collection and was called – although scornfully when Constable used the sobriquet – the ‘English Claude’. In his watercolours the same influences are easily discerned, but the ambition is less strident and he is a sober and truthful unfolder of the picturesque and the romantic in English scenery. One of the identifying characteristics of his style is the use of ‘split brush work’ which he invented as a means of rendering foliage quickly and successfully. This consisted in separating the hairs of his brush into a number of fine points so that by one brush stroke he could represent a number of leaves, as it were, flickering in the breeze. He is also to be recognized by his extraordinary facility in rendering smooth water, a facility which he used to great effect in the sunset compositions which flowed naturally from his fondness for Claude. These tricks become mannerisms, and so prolific an artist could not fail to repeat himself and often be below his true standard; but at his best he brings a fresh and interesting element into the English watercolour school (Fig. 48). Both Glover and Cristall were gifted in the drawing of mountainous scenery, especially that of the Lake District; but whereas Cristall reduces the hills to flat, angular forms, in Glover’s drawings they are softly rounded with gentle, unangular contours.

48 John Glover Landscape with Cattle

52 William Havell Garden Scene on the Braganza Shore, Harbour of Rio de Janeiro

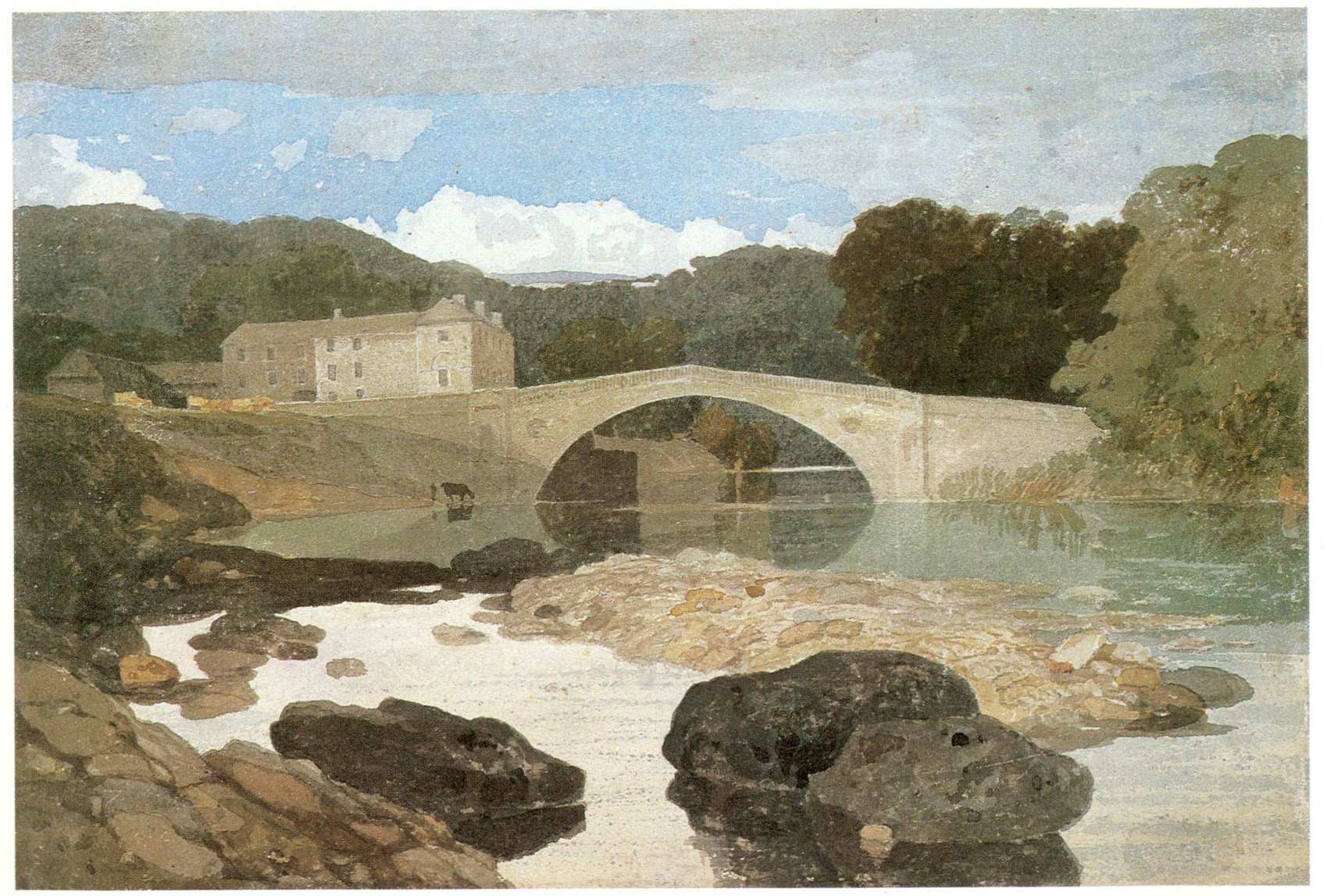

54 John Sell Cotman Greta Bridge

And he was able to develop. When he courageously went to Tasmania in 1831, at the age of sixty-four, the contact with a new landscape infused a more spectacular element into his style.

George Barret was, like Cristall and Glover, approaching his fortieth year when he too became a founding member of the Old Water-Colour Society. He is known as George Barret, junior, to avoid confusion with his father, who was a well-known landscape painter in his day and a foundation member of the Royal Academy. The son, working at the beginning of the nineteenth century, shows the full change in ideas and ideals which had come over the craft of watercolour drawing. Of a dreamy, poetic disposition, his art was latterly so closely modelled on that of Claude that it becomes almost an imitation: almost, but not quite, for the artist’s quiet sincerity has made his own the classical composition irradiated by the glow of the setting sun, the softly tinted cool emptiness of the scene. He had a natural appreciation of these more romantic hours of the day and he wrote this typical passage in his book on The Theory and Practice of Water-Colour Painting:

After the sun has for some time disappeared, twilight begins gradually to spread a veil of grey over the late glowing scene, which, after a long and sultry day in summer, soothes the mind and relieves the sight previously fatigued with the protracted glare of sunshine. At this time of the evening to repose in some sequestered spot, far removed from the turmoil of public life, and where stillness, with the uncertain appearance of all around, admits of full scope for the imagination to range with perfect freedom, is to the contemplative mind source of infinite pleasure.

Barret’s works accord perfectly with the frame of mind he has expressed in these words. His view of Windsor (Fig. 49) is of an ancient castle seen mistily through a grove. He re-creates the mood of Gray’s ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’ and indeed his last work, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, was entitled Thoughts in a Churchyard – Moonlight and was exhibited posthumously with these elegiac verses by the artist:

’Tis dusky eve, and all is hush’d around;

The moon sinks slowly in the fading west;

The last gleam lingers on the sacred ground,

Where those once dear for ever take their rest.

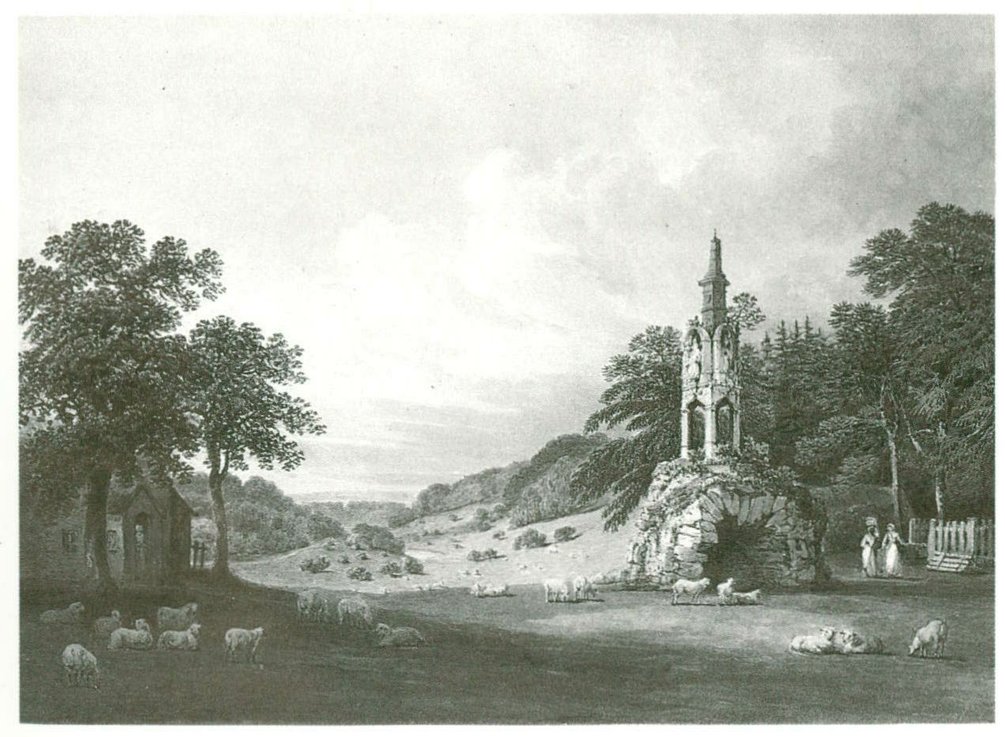

Among the secondary artists who, like Cristall, Glover and Barret, exhibited at the first show of the Society in 1805 were Robert Hills, Francis Nicholson and William Havell. Hills specialized in the drawing of domestic animal life, sheep, cattle, and deer; and he is fairly in the line of distinguished English animal draughtsmen which begins in the seventeenth century with Barlow, goes through the eighteenth century to Stubbs, Morland and Ward, and found a later adherent in the nineteenth century in Landseer. His sketches from the life are carefully studied and full of knowledge and the etchings he made of cattle and ‘groups for the embellishment of Landscape’ were much used by both amateur and professional artists. His A Village Snow Scene (Fig. 50) is a variation upon a theme of Rubens, and was so popular that he made at least three versions of the watercolour. Francis Nicholson, who also showed at the first exhibition of the ‘Old’ Society, was a technical innovator. In seeking a method of rendering highlights on paper he hit upon the expedient of coating the surface with a ‘stopping-out’ mixture based upon beeswax. The large series of views he made at Stourhead show this landscape garden, which had been designed to re-create the images of Claude and Poussin, in its maturity (Fig. 51).

49 George Barret, junior

Windsor Castle

51 Francis Nicholson

Stourhead: The Bristol High Cross

55 John Sell Cotman The Drop Gate, Duncombe Park

58 John Sell Cotman The Lake

William Havell was, at the age of twenty-three, the youngest of the exhibiting members in 1805. His work typifies the common approach of the members of the Society: the dependence of composition on the seventeenth-century landscape painters, the aspiration to vie with oil paintings, the rich tonality of the piece. Havell carried his competition with oil painting so far, particularly after a visit to more exotic scenery, that he incurred the displeasure of his fellow members through the free use of body colour. This was the criticism voiced about his Garden Scene on the Braganza Shore (Fig. 52) when he exhibited it in 1827. He had made the sketch for it on the way to China in 1816.

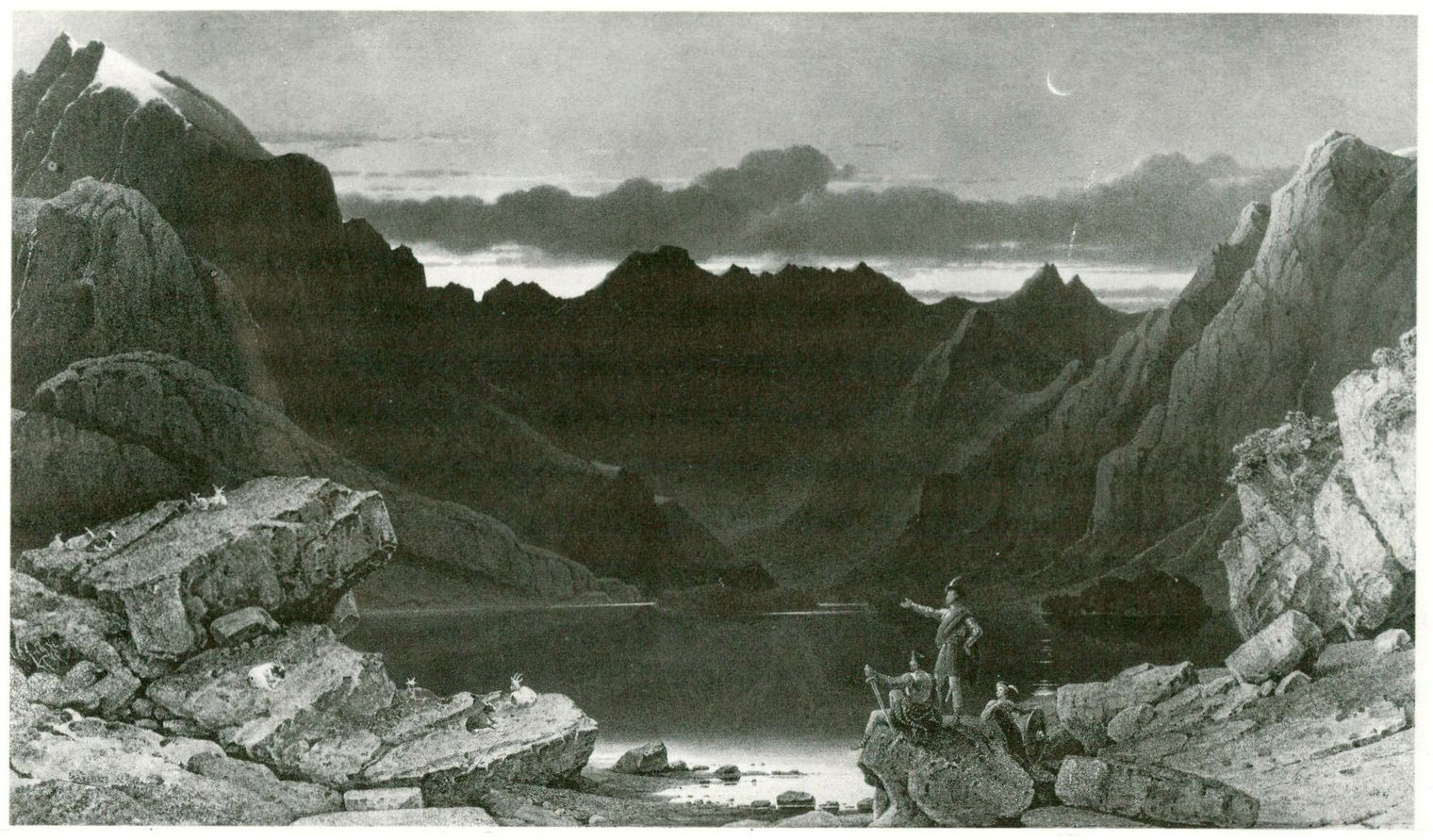

Amongst the next generation of landscape painters George Fennel Robson was conspicuous for the zest with which he rose to the challenge of large compositions framed to rival oil paintings. His early sketching tours were spent in the Highlands, which the writings of Sir Walter Scott had elevated into a primary source of Romantic imagery. His Loch Coruisk (Fig. 53) shows Robert the Bruce humbled by the sublime barrenness of the scenery, and was exhibited with a quotation from Scott’s ‘Lord of the Isles’:

Rarely human eye has known

A scene so stern as that dread lake

To enter fully into the atmosphere of such scenes he had wandered over the mountains dressed as a shepherd, with Scott’s poems in his pocket.

The success of the original Society of Painters in Water-Colours (the Old Water-Colour Society) led to the formation in 1807 of the rival Associated Artists in Water-Colours. This was relatively short-lived, but was replaced in 1832 by the New Society of Painters in Water-Colours which continues now as the Royal Institute of Painters in Water-Colours. These specialized groups played an important part in promoting patronage and in furthering the careers of their members. However, they became exclusive, self-perpetuating bodies, and many highly talented painters did not receive a just measure of recognition from them. For instance, John Sell Cotman is now regarded as one of the greatest watercolour painters of the English school, yet he was subjected during his lifetime to almost complete neglect. The reasons for his lack of success, insofar as they can be explained, lie largely in his own temperament. He had a manic-depressive disposition; wildly elated for a period, he would then be paralysed by the depths of depression. To this example of the supposedly modern artistic temperament was added another feature reminiscent of contemporary careers: that is, that his really creative and original work was done over a relatively brief period when he was young, and though thereafter from time to time he made new and exciting discoveries he was never again quite able to renew the first fine careless rapture of his youth. Though this may seem the index of a modern temperament, it is really the Romantic genius, comparable with the blazing youth of Byron, Keats and Shelley. If the artist of the eighteenth century felt such vagaries of emotion flowing in them they concealed the fact as best they could: the madness of J.R. Cozens and of Clare, the poet, may have been occasioned by such a make-up; but in the early nineteenth century there were fewer reins on sensibility, and the letters of John Sell Cotman alone give a clear index to his lovable, extravagant and wildly unstable character.

J.S. Cotman was born in Norwich in 1782; and, having decided that he must devote himself to art, came to London at the age of sixteen or seventeen in 1798. Here he was befriended by Dr Monro, and became another instance of that connoisseur’s remarkable flair in choosing promising young men. As were Turner and Girtin five years before, he was set to copy outlines and trace drawings. So far as the early formative influences on his style can be identified, the strongest is that of Girtin, filtered perhaps through that of Edridge. But before his visits to Dr Monro, Cotman had undertaken the hack-work of hand-colouring aquatints at Ackermann’s Depository. It would be easy to overestimate the effect of this sort of drudgery on a young artist’s development – Turner and other watercolourists had coloured prints by hand in their time. But in the greatest of his original work which he produced four or five years later, Cotman shows such a love of the flat, unmodulated wash, such a precise control over its edges, and such a delight in the juxtaposition of bright colours, that one is tempted to trace the origins of that style to this very occupation. And just such a predilection may have been strengthened by the sight of Cristall’s watercolours with their emphasis on structure and angularity.

53 George Fennel Robson Loch Coruisk and Cuchullin Mountains, Isle of Skye

Cotman lived the typical life of the young artist struggling for recognition in the London of his day. He hawked drawings round the print-sellers’ shops, lived with like-minded companions, went with them on sketching tours in the country in the summer, and was a member of a sketching club. These sketching clubs have some importance both as a symptom and a cause of the increasingly poetical trend of watercolour painting from the year 1800. Girtin had been a founder member of the club of which Cotman became a member in 1801, and it followed the very simple regimen of meeting by turns in each member’s rooms, to draw from imagination an illustration to a striking passage chosen from the poets. The poets chosen for illustration included Ossian, Thomson and Gray. Such a club provided the perfect counterpart to the visits to Dr Monro: at Monro’s the mechanical copying and tinting of outlines gave training to the hand and executive talents, whereas in the sketching clubs niceties of execution were set aside and the imaginative faculties of the members were given full play. Cotman’s contributions included striking fantasies on such Ossianic subjects as ‘They came to the Halls of the Kings’.

59 John Varley Snowdon from Capel Curig

60 John Varley Hackney Church

Cotman went on a summer sketching tour to Wales in 1800, and on three successive years to Yorkshire, in 1803, 1804 and 1805. These visits to Yorkshire were the great liberating experience of his life; in the course of them his style developed naturally into its full originality, and his treatment of what he saw was lyrically fresh. On each occasion he stayed with the Cholmeleys of Brandsby, a family which had befriended him, and on the last visit he went farther north also to stay with the Morritts at Rokeby Park, on the River Greta. The finest of all Cotman’s watercolours are connected with this stay of his at the River Greta: for instance, his Greta Bridge, now in the British Museum (Fig. 54), and his Drop Gate, Duncombe Park (Fig. 55). These are drawings in which everything inessential is ruthlessly suppressed and yet every nuance of the scene is there. In them, Cotman adjoins to his perfectly controlled washes a deep and vivid sense of colour harmony.

56 John Crome Landscape with Cottages

And yet, probably because of their originality, these drawings did not sell; it was at this stage, and at the early age of twenty-four, that Cotman’s career began to go wrong. Instead of staying in London he returned to Norfolk, where the local school was making its name, and had recently held its first public exhibition. Its most eminent member, John Crome, mainly worked in oils, but made a few low-toned watercolours in which he applied his affection for the Dutch artists to the East Anglian scene (Fig. 56). Cotman also planned, it seems, to tackle the problems of painting in oil. But the prestige of the Norwich school was one thing, its economic basis quite another. Thenceforward Cotman’s means of subsistence were an anxiety to him and became easier only by the acceptance of appointments as drawing master. Yet in the intervals of hack-work, which was particularly perilous for one of his unstable temperament, he found it in him at times to reproduce the cool, smooth crispness of his Yorkshire period.

When he moved to Yarmouth under the patronage of Dawson Turner the sight of the sea with its animated succession of shipping led him to create The Dismasted Brig (Fig. 57) in which the emotion caused by the foreboding of disaster is enhanced by the consummate control of the sharp-edged, flat washes of watercolour. With the encouragement of his patron he became an enthusiastic antiquarian; he turned out scores of drawings of Norfolk churches, and he paid three visits to Normandy in quest of early architecture. But at other times, when he was convinced that the public did not like his style, he tried to paint in a more acceptable manner; then his watercolours fell into the contemporary heresy of vying with oils, and they became hot and arid in colour, flamboyant and artificial in feeling.

At length, at the age of fifty-two, he accepted a post as drawing master at King’s College, London. He entered on it in a fit of enthusiasm as a chance of escaping from his financial distress and of reappearing in the centre of the British cultural world. But the change did not do as much as that for him; his duties involved the manufacture of hundreds of drawing copies with the aid of his family, and he was subject to the same acute ups and downs of feeling. Even then, during the last years of his life he produced a mystical and tempestuous series of drawings of Norfolk scenery, and some watercolours of which both the style and medium were a new development (Fig. 58). These drawings were made with a paste medium believed to be derived from rotting flour; and with something of the luminosity of oil Cotman produced serene and penetrating works, apparently for his own eye alone, which are completely satisfying.

57 John Sell Cotman The Dismasted Brig

61 David Cox The Pont des Arts and the Louvre from the Quai Conti, Paris

63 David Cox Haddon Hall: The River Steps

Cotman might well have been expected to become a member of the Old Water-Colour Society but was not elected when he applied in 1806. After his retreat to Norfolk he seems to have intended to devote himself to oil painting. At any rate, whatever the reason, he lost touch with this and all other representative London artistic institutions. He did not become an associate member till 1825, when he exhibited with the Society for the first time, and never obtained full membership.

The next important watercolourist of the early nineteenth century to attract attention is John Varley. He was a foundation member of the Old Water-Colour Society and one of its most prolific exhibitors, being represented by no fewer than forty-two drawings in the first of its exhibitions. In the thirty-nine years in which he was connected with the Society he sent as many as 700 works to its exhibitions. His disposition was completely opposite to that of Cotman, being uniformly sanguine, and he enjoyed a great vogue both as a painter and a teacher; yet his outward prosperity was scarcely greater than Cotman’s, for he was a reckless spendthrift and was constantly in and out of the debtors’ prison.

John Varley attracted the notice of Dr Monro at the age of twenty and, like the other young men of talent who were recognized by that connoisseur, was set to copying, a year or two before Cotman’s entry on the same scene. The strongest influence upon his early style, naturally enough, as it was the strongest influence in England at the close of the eighteenth century, was that of Girtin. A visit to Wales developed in him a predilection for mountainous scenery of which the recollection remained with him to his latest work (Fig. 59). But he was not without higher ambitions, and sought to extend the range of his subject matter by compositions on such subjects as Scene from the Bride of Abydos, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, an illustration to Byron showing a thousand tombs and cypresses against an evening sky. He was also fertile in his search for new techniques, and just as Cotman had developed his rotting flour paste mixture to bring some of the depth and richness of oil into watercolour, Varley sought to achieve the same result by the lavish use of gum and even by varnishing his drawings.

There was curiously blended in Varley a mixture of the scientific and the visionary faculties, and he did not really succeed in bringing both sides of his nature to full fruition in his drawings. There can be little doubt that he was what we now call ‘psychic’. There are many convincing accounts of his flair for premonitions, and an impressive list of prophecies by him which were subsequently and unaccountably verified. Yet this taproot which he had into the occult did not serve, as it served Blake, to nourish the imaginative content of his art. He is a craftsman of great accomplishment, but in essence a manufacturer of picturesque scenes to a formula. It is a respectable, even an attractive formula, derived from the study of Gaspard Poussin and Claude; but once the key of the formula has been comprehended it becomes a little wearisome. In some of the early work there are signs of greater possibilities, of an imaginative creation out of nature, but the preponderance of stereotyped drawings by Varley is easily understood. He was extremely facile, and when drawings were needed overnight to furbish up an exhibition he would produce what were known as ‘Varley’s hot rolls’. An assiduous practice as a drawing master and the harassing nature of his debts prevented him from concentrating his vision or having frequent recourse to its springs; and there is again his own remark, ‘Nature wants cooking’, to explain these shortcomings. Yet it is when he conceals the culinary process that he is at his most convincing, as in his Hackney Church (Fig. 60). The apparent spontaneity of this scene which Varley had known from childhood – he was born in a house overlooking the churchyard – is explained by the artist’s note on the back ‘Hackney Church, a Study from Nature, J. Varley, July 21st, 1830’.

Unrestricted praise, however, may be accorded to Varley’s activities as a teacher. In imparting the principles of watercolour painting he undoubtedly had the root of the matter in him, and it is as a teacher, in the work of his pupils and those who came indirectly under his influence, that he made his abiding contribution to this branch of English art. When it is remembered that men of such diverse gifts and temperaments as David Cox and Samuel Palmer, F.O. Finch and Copley Fielding were his pupils it will be apparent that he did not impose his own vision on his scholars but, as education truly signifies, drew out of them what was latent in them. One reason for this excellence is to be found in his published Treatise on the Principles of Landscape Design which is an admirably sustained logical analysis of its subject, and emphasizes the need for breadth in a drawing at the expense of too great attention to detail. ‘Every picture should have a “look there!”’ he is reported to have said. He considers that contrasts of all kinds, in shape, colour, texture and movement, are the true exercise of art. In another pregnant saying he records that oil painting may be compared to philosophy while watercolour drawing resembles wit, which loses more by deliberation than is gained in truth.

Hitherto, with the notable exception of Cotman, the members of the Old Water-Colour Society whose work has been considered were artists already established or whose talents had become apparent by its foundation in 1805. Any such society has very soon to exercise itself about the recruitment of new talent. In this first decade of is existence the Old Water-Colour Society chose wisely, and picked from a very large field of professional artists many of whom we may say, being wise after the event, that they were the best watercolourists of the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Of the new blood thus judiciously introduced, the three outstanding men were Peter De Wint, who became an associate in 1810 and a full member in 1812; A.V. Copley Fielding, who also became an associate in 1810 and a full member in 1812; and David Cox, who became an associate in 1812 and a full member in the same year. David Cox was, however, a year older than De Wint and five years older than Fielding, and therefore deserves precedence of treatment.

Cox did not frequent the house and collection of Dr Monro, but he graduated to painting through what was perhaps an even more prolific channel of supply for artists at this period – that is, scene-painting for the theatre. As it had been for David Roberts, Clarkson Stanfield and many others, theatrical scene-painting was the means whereby Cox emancipated himself from his restrictions; in his case, of poor chances in his native Birmingham which he left for London and eventual recognition as one of the most characteristic of the English watercolourists. He came to London about 1805, fell under the influence of Girtin and had lessons from John Varley. Nor is it surprising that while he was learning to feel his feet he should have copied in watercolours a typical painting by Gaspard Poussin which was in a dealer’s shop at the time. This painting of a ruin in a dark setting of trees, with a shepherd and his flock in the foreground, and pervaded by the evening light, exercised a great influence over the watercolours Cox painted in the next fifteen years and more.

65 Peter De Wint Gloucester from the Meadows, 1840

68 John Constable Cottages on High Ground

Cox maintained that Wales could provide all the scenery necessary for the Romantic vision. Yet his few excursions abroad enriched his production with one of his most carefully contrived and colourful compositions, the Pont des Arts and the Louvre from the Quai Conti (Fig. 61), worked up from a sketch he made during his only visit to Paris in 1829.

The Cox whose work is most familiar in private collections and art galleries is the later Cox, the Cox of windswept heaths, stormy seas, and effects of atmosphere and light; but for the first two decades of his maturity he worked in another more traditional and more solid way. During that period he produced a number of technical treatises embodying his teaching on the theory and practice of watercolour painting, and these reveal him as an exponent of the eighteenth-century idea of the picturesque, modified by the technique of such of his contemporaries as Varley. There is something monumental and satisfying about Cox’s treatment of the picturesque. He translates the logical construction found in Poussin and makes it fit much more closely to the English landscape than Varley, in whom the machinery is often too apparent. There is also less potboiling and uninspired repetition of themes in this earlier manner. But, despite the vagaries and lapses of the later style, the critical judgment is right which sees in it Cox’s greater achievement and more original contribution to our art. It is difficult to resist the temptation of calling it an anticipation of Impressionism, because of the sensitiveness to light and transient effects of atmosphere displayed in this later style. There may indeed be the relation of cousinship between the style of Cox and that of the early Impressionists. The nearest French equivalent to Cox is to be found in Eugène Isabey, and both Cox, after his visit to France in 1829, and Isabey learned much from the airy, featherlight brilliance of Bonington. Isabey was of importance to the development of Boudin, who in his turn was a decisive influence upon Monet.

But whether these considerations are well founded or not, Cox does, in the best of his later work, introduce the elements – wind and wave, air and water and light – as dramatic motives. They sweep across the unchanging landscape, they almost engulf the traveller on his way. Such conceptions are a welcome contrast to the monumental calm of the founders of the English watercolour school and of Cox’s own earlier style (Figs 62, 63).

De Wint dominates the watercolour painting of the second quarter of the nineteenth century with Cox and Copley Fielding. He had been apprenticed, while still in his teens, almost at the beginning of the nineteenth century, to learn engraving and portrait painting, but his native bent for landscape painting asserted itself so strongly that he was released from his indentures and enabled to follow his desire. He was also at about the same time introduced to Dr Monro, and in his collection of English watercolour drawings admired those by Girtin most. He enjoyed steady, if modest, patronage as draughtsman and as teacher almost from the outset, but his period of wider fame is to be dated from the time when he rejoined the Old Water-Colour Society in 1825. He had more right than most of his contemporaries to attempt to emulate in his watercolours the richness and depth of colour of oil painting, for he was himself by preference a painter in oils. The surviving examples of his work in this medium show how adequate his technique was to express the whole range of his ideas. In their turn the oil paintings serve to explain his fondness for a deep, harmonious colouring, pervaded by a love of the strawberry roan colour of the cows which are so inevitable a feature of his landscapes.

62 David Cox The Night Train

De Wint is the most decided of the followers of Girtin, and especially he found in him encouragement for the painting of the flat and at first sight featureless Midland counties in which he felt most at home. So wedded was he to the long level expanse that the very shape of his drawings reflects this liking of his: they are often abnormally long in proportion to their height and sometimes give the impression of a strip to which additions can be made indefinitely. Rather than seek the orthodox sources of the picturesque, De Wint would spend summers in the neighbourhood of Lincoln drawing not only the cathedral in its magnificent position but also the surrounding fields, marshes, swamps and the alleyways of the city (Fig. 64). If Girtin had not performed similar wonders before him there would be all the more reason to be amazed at the interest and variety, the sense of warmth and humanity, which De Wint conjures from this unpromising scenery.

69 John Constable Stonehenge

70 John Constable London from Hampstead, with a double Rainbow

64 Peter De Wint Old Houses on the High Bridge, Lincoln

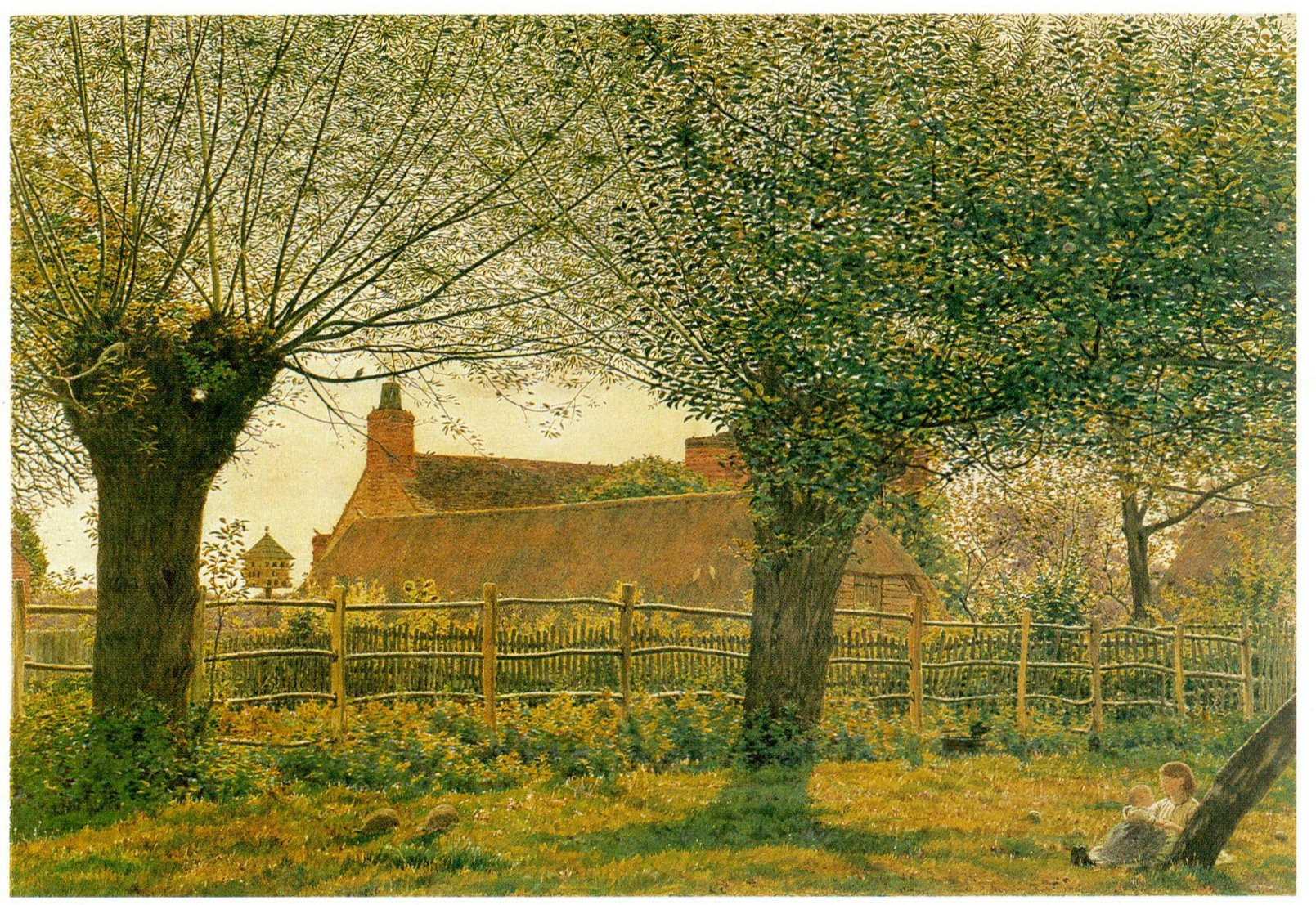

He united in a high degree the powers of generalizing with the power of concentrated design. He does not in his best works carry the drawing of his foliage or his architecture to a high degree of definition: it is all adequately stated in the language of the sketch, and yet each part is governed by a profound and concentrated sense of structure and of its place in the unity of the whole scheme. It is our confidence in the artist’s power of synthesis which gives so satisfying a sense of completeness and repose to our contemplation of his work. He does not greatly vary his subject-matter in search of wildly romantic scenery, or to play upon a range of atmospheric effects. His theme is generally the immemorial one of the English countryside, watched over by the cathedral (Fig. 65) or the scene of haymaking in the summer days; or possibly it may be the low level reaches of a river with antiquities mirrored in its calm, grey surface. It is set down naturally and in accordance with De Wint’s innate sense of design, and always with his singularly rich power of colouring. When, unusually for a watercolour painter at this time, he set out to paint a still life, his delight in the precocity of his technique, and his control of contour and wash, is quite apparent (Fig.66).

As befits his approach to art, which was neither derivative nor the fountainhead of a new departure in the school, De Wint’s attitude to his fellow artists, as with dealers, was standoffish and remote. But one of his contemporary landscape painters bought from him, and that one was John Constable. There could be no greater tribute to De Wint’s artistic integrity.

66 Peter De Wint Still Life

To his contemporaries of the second quarter of the nineteenth century the fame of Copley Fielding stood equal with that of Cox and De Wint, but his reputation does not bear the same scrutiny today. He prospered exceedingly and made a large fortune by his art, in times when De Wint was content with moderate prices, Cox was not prosperous, and Cotman chronically the reverse of prosperous. Here is some concrete evidence for the oft-repeated assertion that the taste of the new class of art patrons was on the decline in this epoch. But we must not judge them too harshly, for Ruskin too, while admitting that Copley Fielding had faults, was moved to accord him a very high place in art. When preparing his readers for his declaration of the full superiority of Turner in the first edition of Modern Painters, Ruskin enrolled Copley Fielding amongst those who were more beautiful, more true, more intellectual than Poussin and Claude, typifying him as ‘casting his whole soul into space’. A more balanced nineteenth-century judgment on him reads: ‘He fell into the most rigid mannerism of self-repetition, crudeness of colour, and feeble or blurred confusion of detail, and yet from isolated specimens of his work it might seem as though he might have been second only to Turner among water-colour artists.’

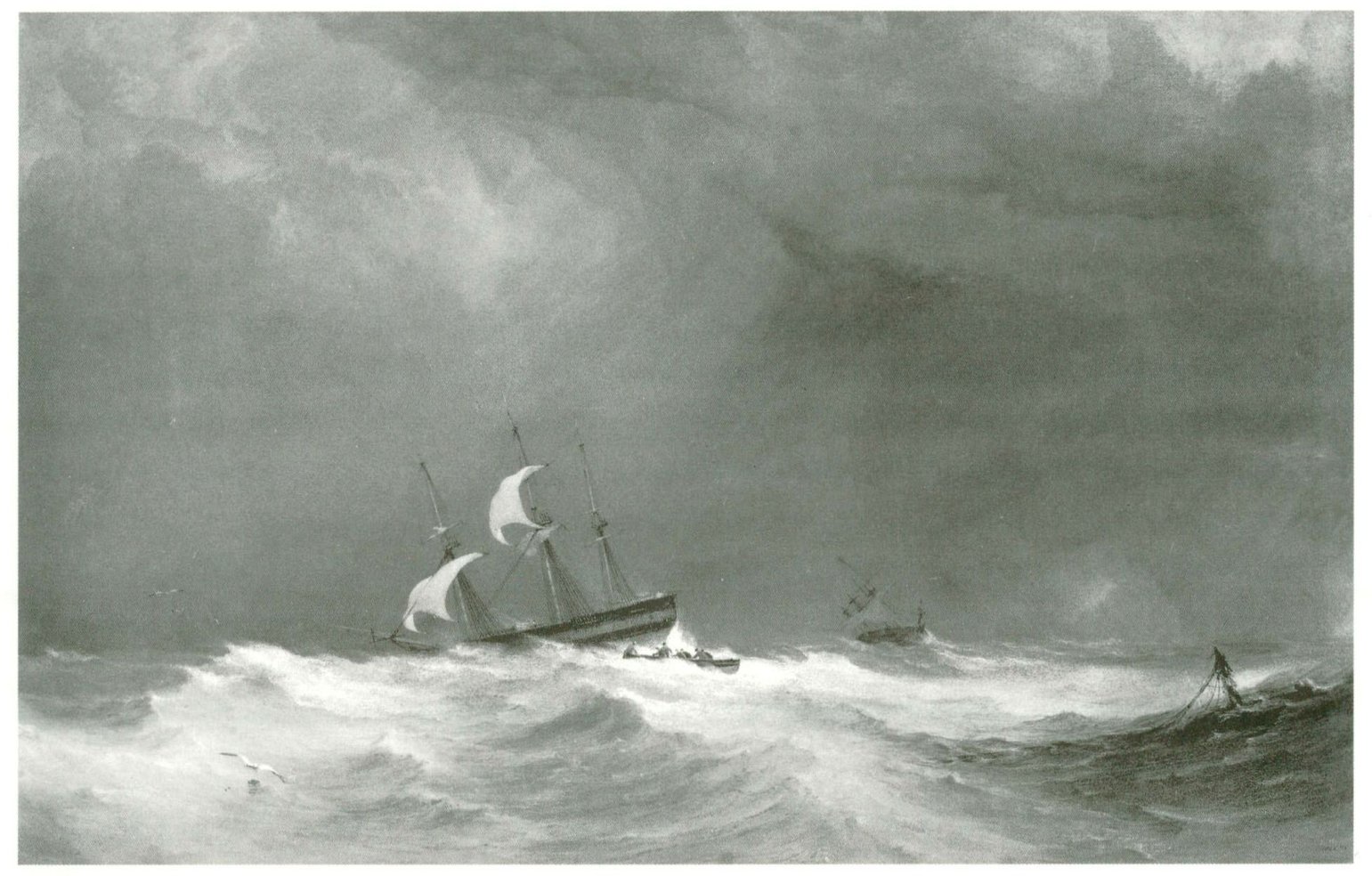

Copley Fielding came to London in 1809 and it is said that when he presented himself to John Varley he showed so little aptitude for improvement that Varley did his best to dissuade him from following the career of an artist. He frequented Dr Monro’s, and his drawings of this early period show an almost slavish devotion to Varley’s principles. Once he had sketched out for himself the formula he repeated so often, of moorland and distant hill, with a brown, undifferentiated foreground traversed by a rutted path, he never failed of success. His only other development took place when, on an enforced sojourn at Brighton for his wife’s health, he fell under the spell of the sea (Fig.67). Thereafter sea pictures bulked equally with distant mountains and moorland mists in his work. He was, if possible, even more prolific and facile in execution than John Varley and, in the course of fifty-four years, exhibited the surprising total of 1,671 drawings with the Old Water-Colour Society. He was President of the Society, and thus the official representative of English watercolour, for the last twenty-five years of his life.

71 R.P. Bonington Medora

73 R.P. Bonington A Venetian Scene

67 A.V. Copley Fielding A Ship in Distress

It is a relief to turn from Copley Fielding to an artist whose originality and single-minded devotion to the highest potentialities of his art are beyond doubt. John Constable does not come to mind in the first instance as a member of the school of watercolourists: for one thing, he himself during the greater part of his maturity thought and worked so thoroughly in terms of oil painting that his use of watercolour was spasmodic and secondary. But to be the painter of the complete truth of nature, as he set out to be, Constable had constantly to be out in the fields making notes of the scene before him, often in pencil, often in oil, but sometimes, and more frequently toward the end of his life, in watercolours.

Constable succeeded in freeing himself entirely from the habits of vision and picture-making with which we have become familiar in this survey – in particular from the ‘picturesque’ tradition of composition. He saw and drew things as they were, without tricks of style, and so when he came to use watercolours in the period of his full mastery, he did so with originality and a new expressiveness. But these works of his maturity were preceded by a remarkable group which he produced in 1806, when he was thirty years old. Constable was unusually late in developing, and started with far less manual dexterity than most of the precocious youths who became famous artists. In 1806 he paid his solitary visit to the Lake District. Leslie records in his Life of Constable that the artist did not feel at home in the mountains of which the solitude and vastness depressed him. He exhibited a few finished oil paintings and then dropped the theme of the Lakes abruptly from his repertoire. At the time he had made a remarkable series of watercolours, the majority of which stayed in his keeping. These drawings betray unmistakably the strong influence of Girtin, but they are the fruit of incessant and excited sketching, and in their unpretentious way they express as no other series of drawings or paintings has done the very qualities by which Constable was oppressed – the solitude and the grandeur of the hills. Both from the drawings themselves and documentary evidence we know they were made by the artist on the spot, mostly sitting in Borrowdale in the presence of the majestic massifs. To his contemporaries at this time Constable’s style was sufficiently exceptional to give them the impression that he was aiming for effect; but on the back of some of these Lake District sketches we find notes by the artist comparing what he has seen and attempted to draw with specific paintings by Gaspard Poussin, thus emphasizing once again the dependence even of our most original minds on the main tradition of seventeenth-century landscape.

When after this brief early experiment he took to watercolour again in the later phase of his career, Constable was fully aware of what he was seeking in nature. To be a natural painter he had to drop all tricks of composition, all purely formal rules of picture-making. At the same time he had to express the evanescent no less than the permanent: the ever-changing shapes and colours of the clouds he had watched avidly since his childhood as the son of a miller, the white of leaves beaten up by the wind, the dew on grass and sunlight on tree stumps. All these functions of changing light and colour were to be part of his expression of the outer world. Watercolour became a handmaid to his pencil and his oil colours in catching these transient appearances at the moment they were seen. The unpremeditated method of their use and the self-trained and scrupulous honesty of Constable’s vision ensured the freshness of these sketches, whether cloud studies or notes of buildings, trees or country (Fig.68).

In the last years of his life he took to exhibiting watercolours as finished expressions of his art. This course was partly forced upon him by illness; in 1834 he was only able to send four drawings to the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition. One of them was a large watercolour of Old Sarum, in which he developed his technique to express his sense of the evanescent qualities of light. He carried this method even further when he exhibited his watercolour Stonehenge in 1836 (Fig.69). This is an intensely Romantic rendering of the emotions evoked by ancient, inexplicable ruins, and its poetry is enhanced by the double rainbow which he cherished as a brilliant phenomenon of light and as a symbol of hope (Fig.70).

74 Thomas Shotter Boys The Boulevard des Italiens, Paris

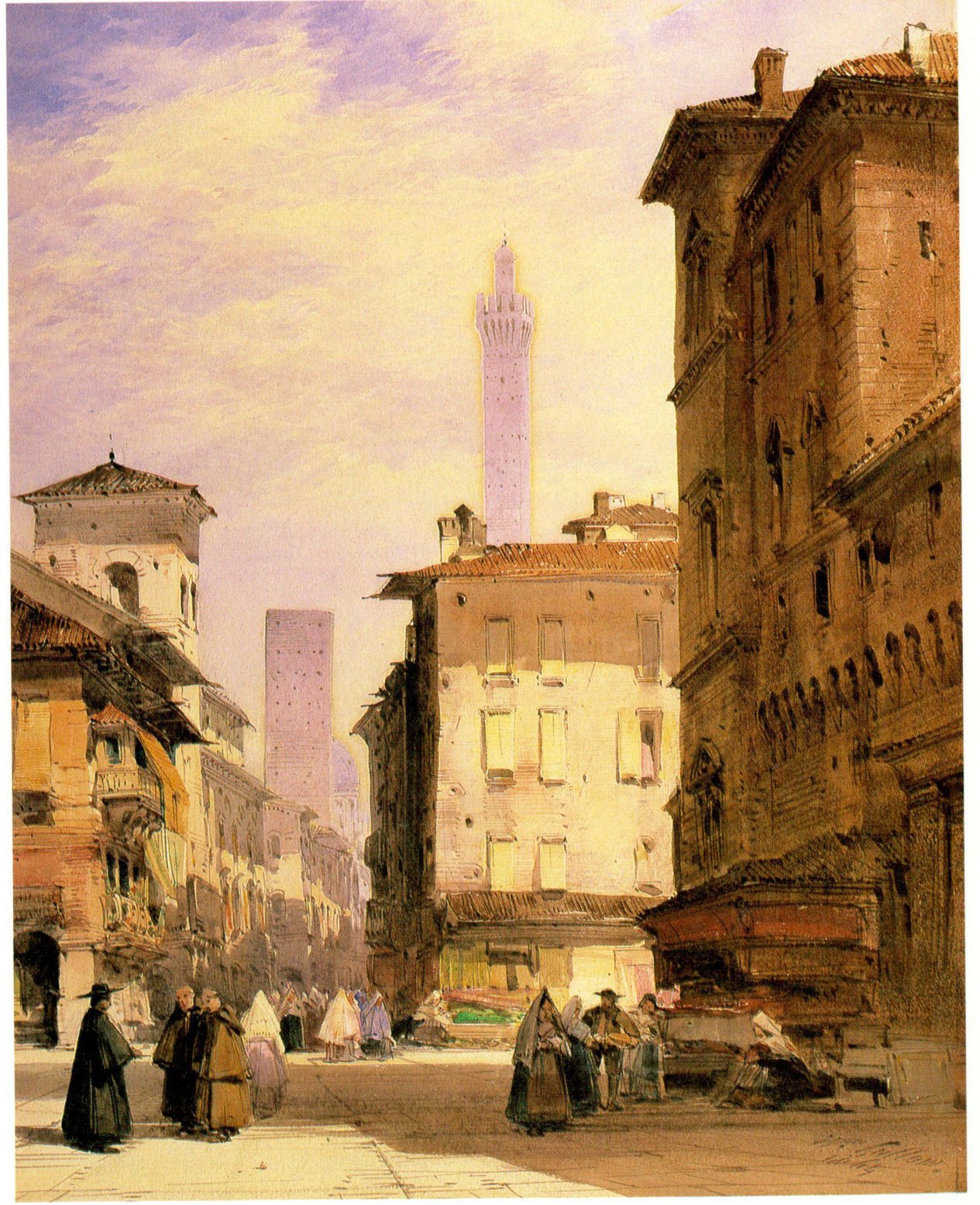

76 William Callow The Leaning Tower, Bologna

It is from another painter who made a great contribution to oil painting that a strong revivifying breath comes to the English watercolour school in the ’twenties of the nineteenth century. Although he only lived to be twenty-five, Bonington crystallized the prevailing tendencies of his time so well that he not only left a body of great work behind him but he had a strong influence on his contemporaries and successors both in France and England. Both English and French elements entered into his training: his father, a landscape and portrait painter of Nottingham who no doubt gave him some training, took him to France at the age of sixteen or seventeen, and it was in France that most of his working life was passed. There the young artist took lessons in watercolour from Louis Francia, who had imbibed the English watercolour tradition in association with Girtin, and was newly set up as a teacher in Calais. Subsequently Bonington went to Paris and worked at one of the foremost studios there; he was much admired for his facility and brilliance of execution, and Delacroix was his friend. He came to share the enthusiasm felt by Delacroix for Byron’s Eastern romances and their star-crossed lovers (Fig.71).

Bonington paid a visit to Venice and made one or two journeys to England. Such was the effect of his watercolours in France at the time of their execution that the young Corot was spellbound and deeply influenced by catching sight of one in a dealer’s window while on an errand. Their predominant characteristic is lightness of touch combined with certitude and accuracy of drawing. He models with the broad, swift strokes of the sketch, but every touch is in place and he does not destroy the first effect of spontaneity by elaboration. The wash has as it were a souffle-like lightness on the paper. Whereas Peter De Wint seems to be drawing in heavy elements, in earth itself, Bonington draws in air and colour.

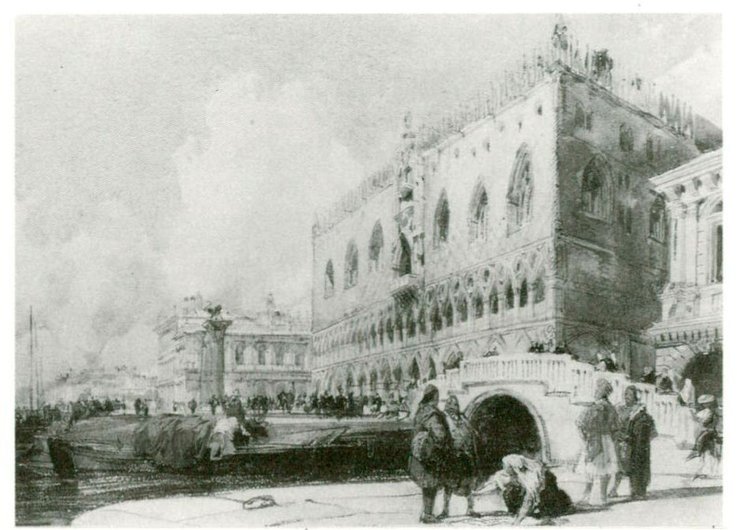

In landscape, Bonington’s favourite subjects were seascapes from the levels of the French coast. He made many topographical street scenes of Paris and other picturesque towns with a delicacy in the treatment of architecture which contrasts strongly with the heaviness of some other topographical draughtsmen, such as Prout. Latterly, when he also came to take up painting in oil, he painted a number of historical pictures in the style of the French romantic school, with members of which he was associating. A visit he paid to Venice in 1826 provided him with fresh opportunities both for picturesque architectural topography and for romantic historical painting (Figs72, 73).

The followers of Bonington felt his influence in both these categories. The lightening of texture in the later works of David Cox seems to be directly traceable to his new acquaintanceship with Bonington’s style. In France his admirers included such artists as Eugène Isabey, who through Boudin exerted an influence on the Impressionists. A whole group of rising artists gave proof of their respect for his methods, the most notable among them being Thomas Shotter Boys, John Scarlett Davis, James Holland and William Callow.

Boys, in particular, made drawings of the Parisian street scene which rival those of Girtin and Bonington. In them the vertical moulding of the repetitive ornament in the architecture are rendered by the fine brisk parallel strokes common to this group, and the skies are drawn with the understanding natural to so many members of the English school of watercolourists (Fig.74). Boys is known to a large public through his lithographic views of Paris, and also by his lithographs of London in 1842, in which with a similar fidelity and appreciation for space he has recorded the image of early-Victorian London. In his earlier work, John Scarlett Davis draws the streets of Paris in a manner which, though it derives from the same example, is more linear and less fluid in handling (Fig.75).

72 R.P. Bonington The Doge’s Palace, Venice

75 John Scarlett Davis The Porte St Martin, Paris

William Callow worked for a time with Boys at Paris and lived abroad between his seventeenth and twenty-ninth years. Like Bonington and Boys, he paid much attention to drawing the Parisian street scene. There was indeed almost a craze at this time among amateurs of drawings for such delineations, stimulated no doubt by the sealing off of the Continent during the period of the Napoleonic Wars. Callow became, like other artists of the second quarter of the nineteenth century, a vigorous traveller abroad in search of picturesque architecture (Fig.76). His career was a remarkable one, for he continued to paint skilfully in the Bonington tradition till the closing years of the nineteenth century and in fact lived until 1908, when he died at the age of ninety-five. He was one of the artists who helped to maintain the standard of the exhibitions of the Old Water-Colour Society in the second half of the nineteenth century, and was secretary of that body between 1865 and 1870.

James Holland was born in the Potteries, and like Renoir began his painting career in the decoration of ceramics. He too became a far-travelled man in Europe, notably in Portugal, which he visited under a commission from a publisher to supply drawings for an engraved annual, and in Venice. It is of Venetian scenes that his most colourful and forceful later drawings were made (Fig.77). In them he made much use of body colour; in brilliance of colour and virtuosity of handling, these drawings represent the method of Bonington pushed to its farthest possible extremes. That Holland knew the value of sketches is established by his remark that ‘parting with a sketch was like parting with a tooth, once sold it cannot be replaced’.

Samuel Prout earned a widespread reputation through his renderings of ancient and picturesque Continental architecture (Fig.78). His most typical works are certainly drawn with uniform, though mannered, ability, colourful and enlivened by gay window-blinds and groups of rather triangular figures. An earlier and unfamiliar phase of Prout’s style, in which he draws in cold greys and low tones, is far more pleasing. The subjects of these works are generally picturesque cottages and hamlets of Cornwall or Devon. But his success was built upon his diligent travels, from which he derived scenes which roused curiosity and conjured up tantalizing desires to follow in his steps. John Ruskin records how his father brought home a copy of Prout’s lithographic Sketches in Flanders and Germany: ‘As my mother watched my father’s pleasure in looking at the wonderful places, she said why should we not go and see some of them in reality? My father hesitated a little, then with glittering eyes said – why not?’ Ruskin repaid his debt to the originator of his foreign travels by enrolling Prout amongst the living artists who had shown their ‘superiority in the art of landscape to all the ancient masters’.

77 James Holland Ospedale Civile, Venice

80 William James Müller Tlos, Lycia

78 Samuel Prout

Regensburg Cathedral

83 William Turner of Oxford Donati’s Comet 1858

The growing taste for travel played its part in enticing artists to make even longer and more adventurous journeys. David Roberts was one of the first to seek novelty and richness of architecture in Spain; then he went even more boldly to Egypt and the Holy Land in 1838 and 1839 (Fig.79).

William James Müller was another early visitor to Egypt and Greece, and in 1843 he became the official draughtsman to the Expeditionary Force in Lycia. The exceptional breadth of his watercolour technique is demonstrated most particularly in the sketches he made on that expedition (Fig.80).

79 David Robert The Great Temple of

Ammon, Karnac, the Hypostyle Hall

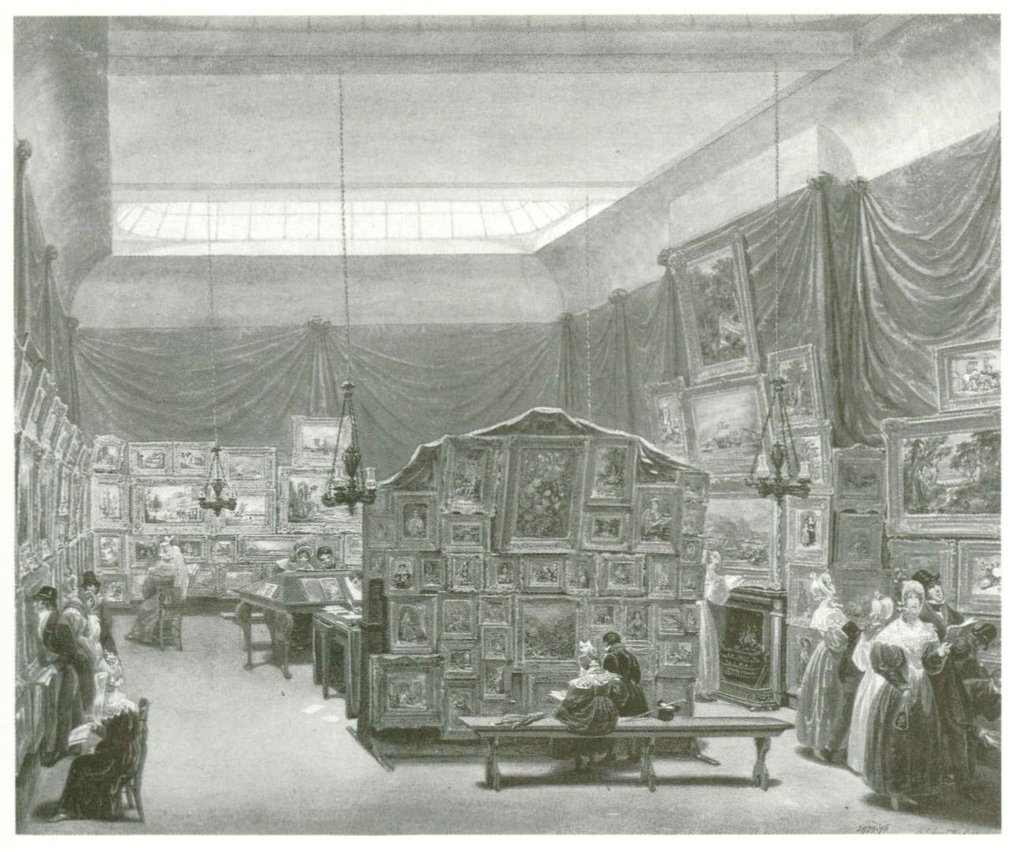

Clarkson Stanfield had, like David Roberts and David Cox, begun his career as a scene-painter; he transferred the sense of drama which this calling entails into his topographical watercolours, and even more into the sea paintings for which he gained a notable contemporary reputation. To Ruskin he was ‘stern and decisive in his truth’. The dangers of the sea needed no emphasizing to this maritime nation; the horrifying number of shipwrecks was a constant reminder of its perils. But the melodramatic note in A Storm (Fig.81) is also to be understood in the context in which it was to be exhibited. George Scharf’s interior of the New Watercolour Society (Fig.82) shows the crowded screens and the heavy frames enclosing large watercolours customary in the exhibitions of these earlier years of the nineteenth century. To make a mark in such surroundings any composition had to be bold and dramatic.

William Turner of Oxford’s Donati’s Comet held the attention of the visitors by its exceptional and moving subject, in spite of its relatively small size amongst exhibition pieces (Fig.83).

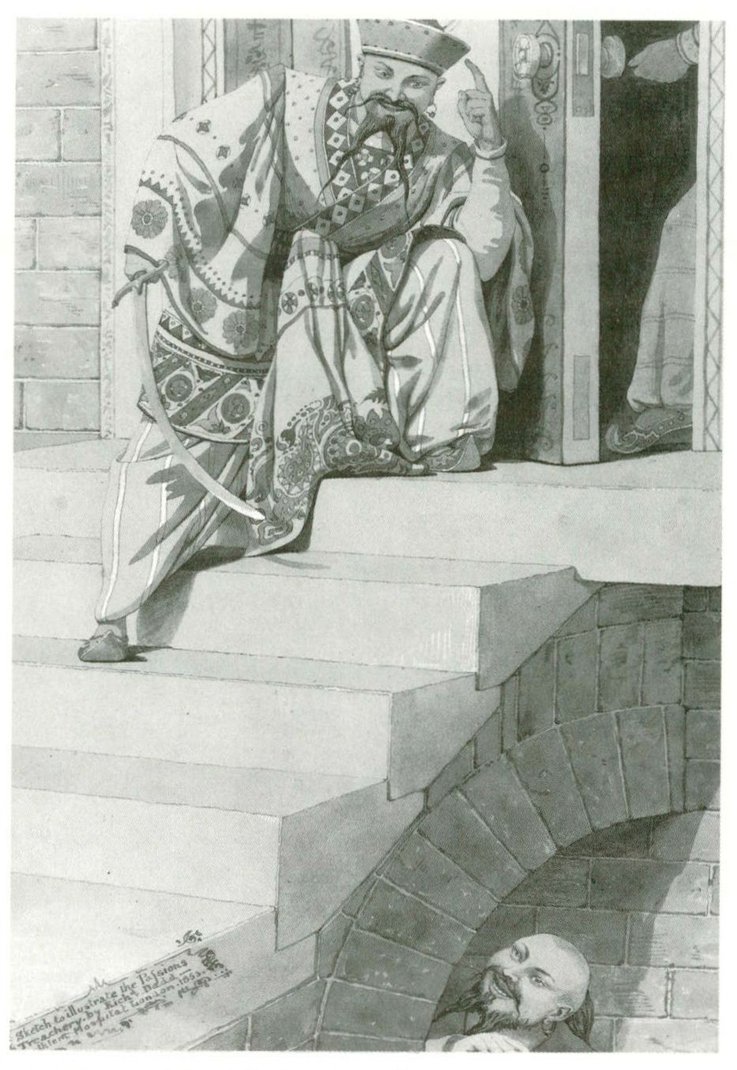

An interest in the historic past was as much a feature of the Romantic movement as the delight in exotic travel. As we have seen, Bonington was an early exponent of scenes set in the supposedly correct costume of an earlier century or an exotic land. Amongst the many watercolour painters who supplied collectors with such reconstructions George Cattermole was one of the most conscientious and prolific. He is probably best remembered now for his illustrations to Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop, which were engraved on wood and are still reprinted; his feeling for old buildings and for antique furniture were well employed in these designs, and culminate in the scenes of Little Nell’s death and her grandfather’s constant watch by her grave.

81 Clarkson Stanfield A Storm

82 George Scharf The Gallery

of the New Society of Painters in Water-Colours, 1834

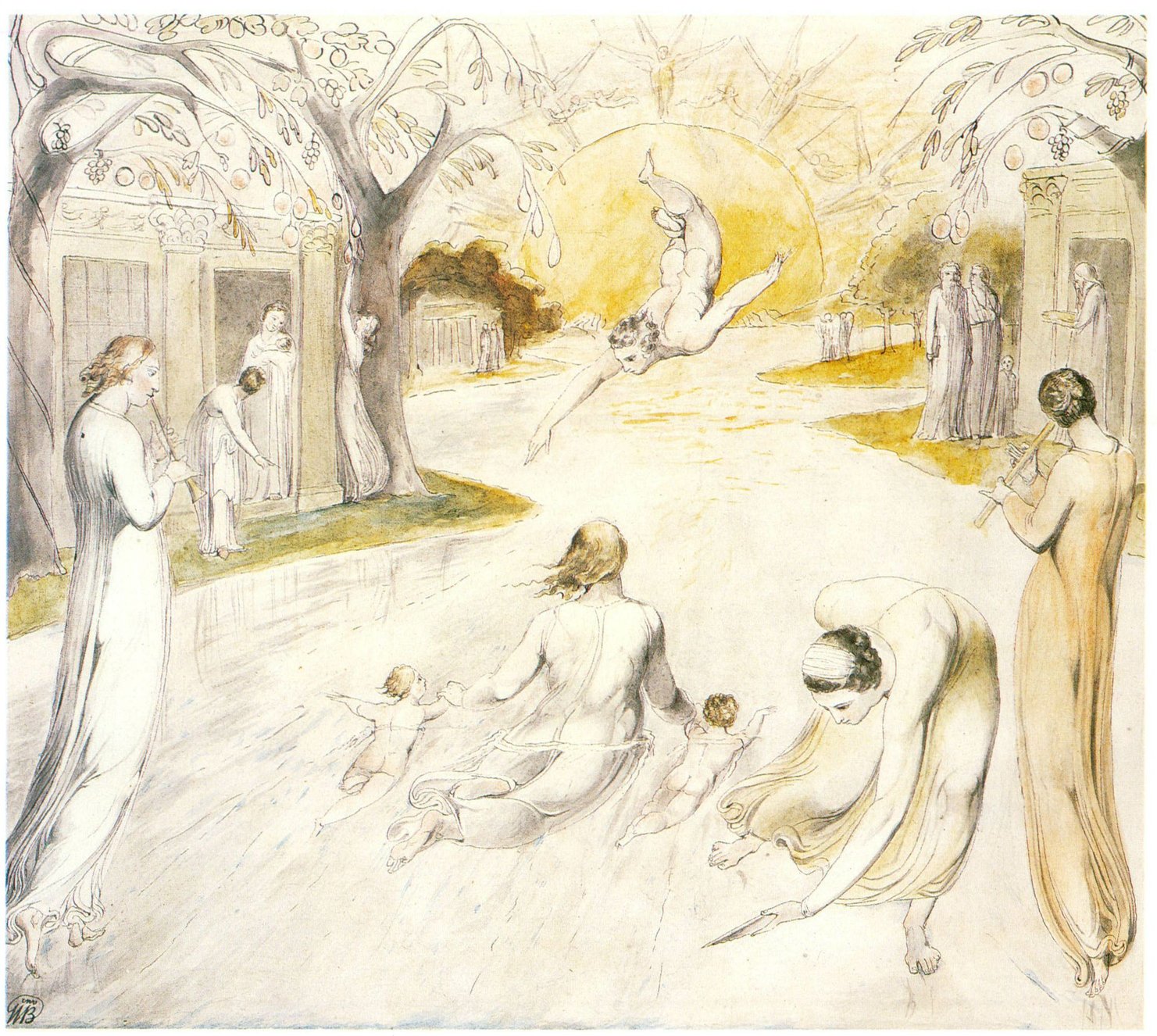

88 William Blake The River of Life

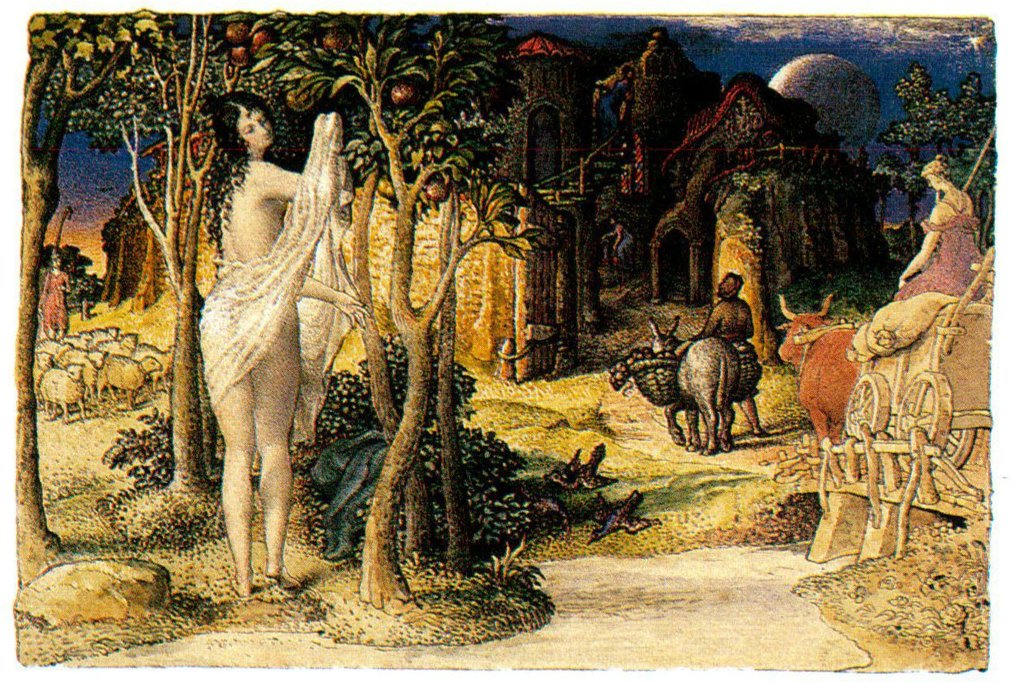

go Edward Calvert A Primitive City

84 George Cattermole Macbeth instructing the murderers employed to kill Banquo

His antiquarianism reflects an essential ingredient of the Gothic revival, and gives a sense of authenticity to his theatrical scenes such as his illustration of Macbeth instructing the murderers employed to kill Banquo (Fig.84).

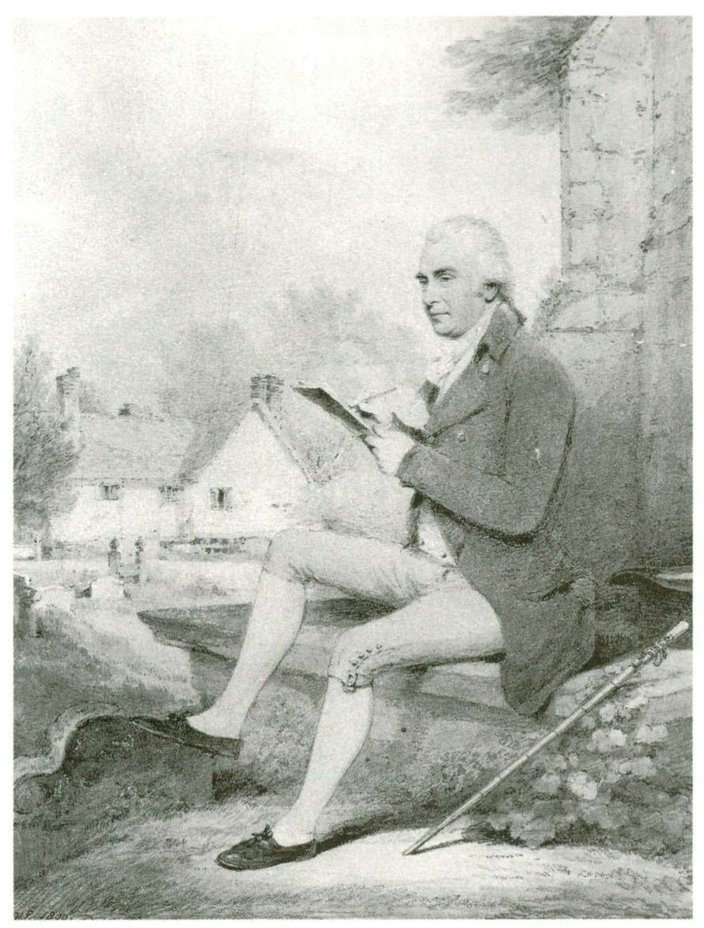

One of the most lively contemporary developments in figurative watercolour painting came through the increasing demand for portrait drawings, as a halfway house between the portrait miniature and the oil portrait. One of the most active in this genre was Henry Edridge, a versatile man who was a successful miniaturist and landscape painter. As a portrait draughtsman he is the nearest English equivalent to Ingres. His drawing of Thomas Hearne in Ashstead churchyard was made in 1800, when the two artists were staying with their friend Dr Monro at his country cottage near Leatherhead (Fig.85).

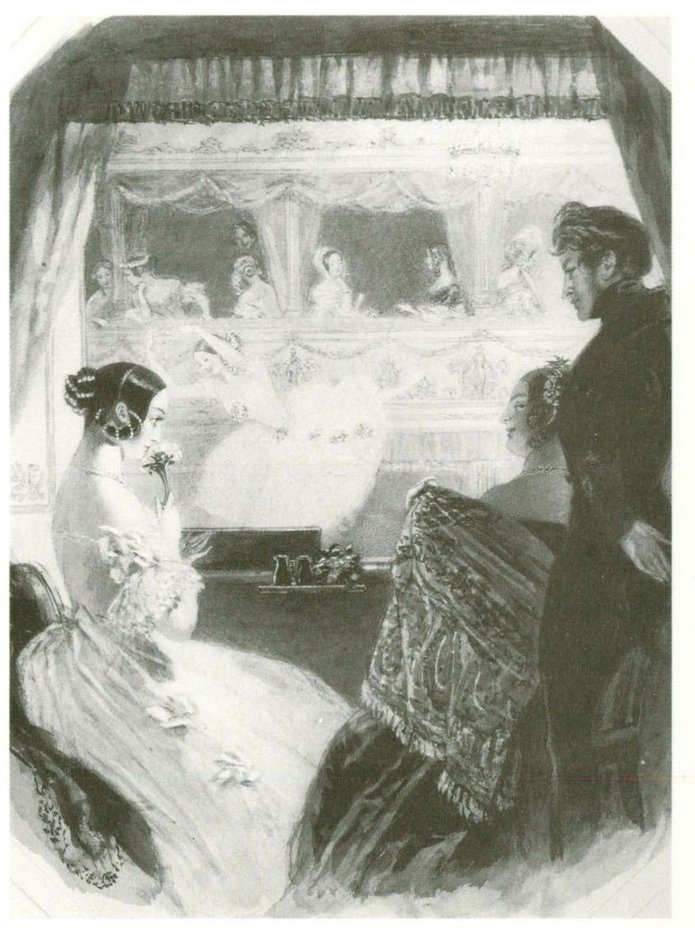

The nineteenth century rebelled against the savagery of eighteenth-century caricature, watering its fury down into the genial comedy of such drawings as A.E. Chalon’s The Opera Box (Fig.86). Whilst the street scenes which had so fascinated the founders of the English watercolour were not neglected, the subject matter was now often taken from the higher reaches of society, as with the visiting French artist Eugène Lami recording a scene in Belgrave Square (Fig.87).

85 Henry Edridge Thomas Hearne in

Ashstead Churchyard, Surrey

86 Alfred Edward Chalon The Opera Box

92 Samuel Palmer In a Shoreham Garden

The artist who most truly brought the eighteenth-century tradition of figurative composition into the early years of the nineteenth century was William Blake. Yet his extensive and powerful influence was spread more by his small number of idyllic Arcadian woodcut landscapes than by the illustrations to his Prophetic Books. If we except one of two friends and patrons, contemporary appreciation passed Blake by. Veneration for him was kept alive by a small cult but it did not become more general till, in the ’fifties, Rossetti, the biographer Gilchrist, Swinburne and others connected with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, began to be aware of his extraordinary merits. The growth of a still more popular appreciation of Blake, which has at length led to his acceptance as one of the great masters of English art, no less than of English literature, dates only from exhibitions of the twentieth century. To take Blake seriously before 1850 was to invite the supposition that one was slightly mad, and in the second half of the nineteenth century it would still have been paradoxical.

Blake’s vision did indeed penetrate through to the fundamentals, but he expressed the difficult truths of which he had caught a glimpse in an art language which was bound to remain inaccessible to most people of his age. For, inevitably, he worked in the artistic idiom of his own day, and used it in a way which to normal eyes seemed a confession of his own technical inadequacy. In his poetry he uses the romantic imagery of Ossian and Gray to achieve results which are a startling anticipation of Wordsworth in the Lyrical Ballads. In his painting he has a variety of contemporary working traditions to draw on. While serving his apprenticeship as an engraver he had made a great number of drawings of medieval tombs, and the impress of the medievalism which he imbibed, consciously or unconsciously, while engaged on this work is evident throughout his original drawings. At the other extreme he was enthusiastically aware of the current academic tradition of drawing the nude figure and of the Michelangelesque emphasis on muscular development which was already being put at the service of expressionistic literary illustration by Fuseli. In this he was touching the deepest aspirations of the English academic circles of the time: the desire to produce a body of historical painting, in which the human figure was the vehicle of an epic message, worthy to be put beside the schools of Italy and Flanders.

Blake put these strands of current ideas to completely individual use. He exaggerates everything in his need to express the overflowing of emotion and enlightenment. When Job is met by his friends – Job’s comforters – they are mostly, in Blake’s eyes, of patriarchal age, terribly old and bowed down, with long, white, flowing beards. His protagonists have the large, staring eyes of the visionary or the madman. They express prostration by being bent to the ground, nobility by upstanding gesture, and yearning with both arms outstretched to the sky. Taking the symbolism of Milton quite literally, God uses a golden compass to strike out the universe. Outspoken expressionism of this type sometimes verges on caricature, but in Blake it generally does not step beyond the limits of what we can accept (Fig.88).

Blake was inexhaustibly fertile in technique. He was trained in the most solid tradition of eighteenth-century line engraving; but he found, when he came to work out his own ideas, that it was difficult to express them in this medium or through oil and watercolour. So he developed a method of relief etching, to which he applied colour by hand, to make of his hand-printed books of poems something as glowing as medieval illuminated manuscripts. When he was over sixty he turned to what was for him the novel medium of the woodcut, and made a dozen designs for Thornton’s Virgil of which the influence was absolutely vital. So, too, he made what are to all intents and purposes in appearance watercolour drawings, but which are in fact colour prints, often derived in somewhat recondite fashion as offprints of frescoes and so forth, and then coloured again or finished by hand.

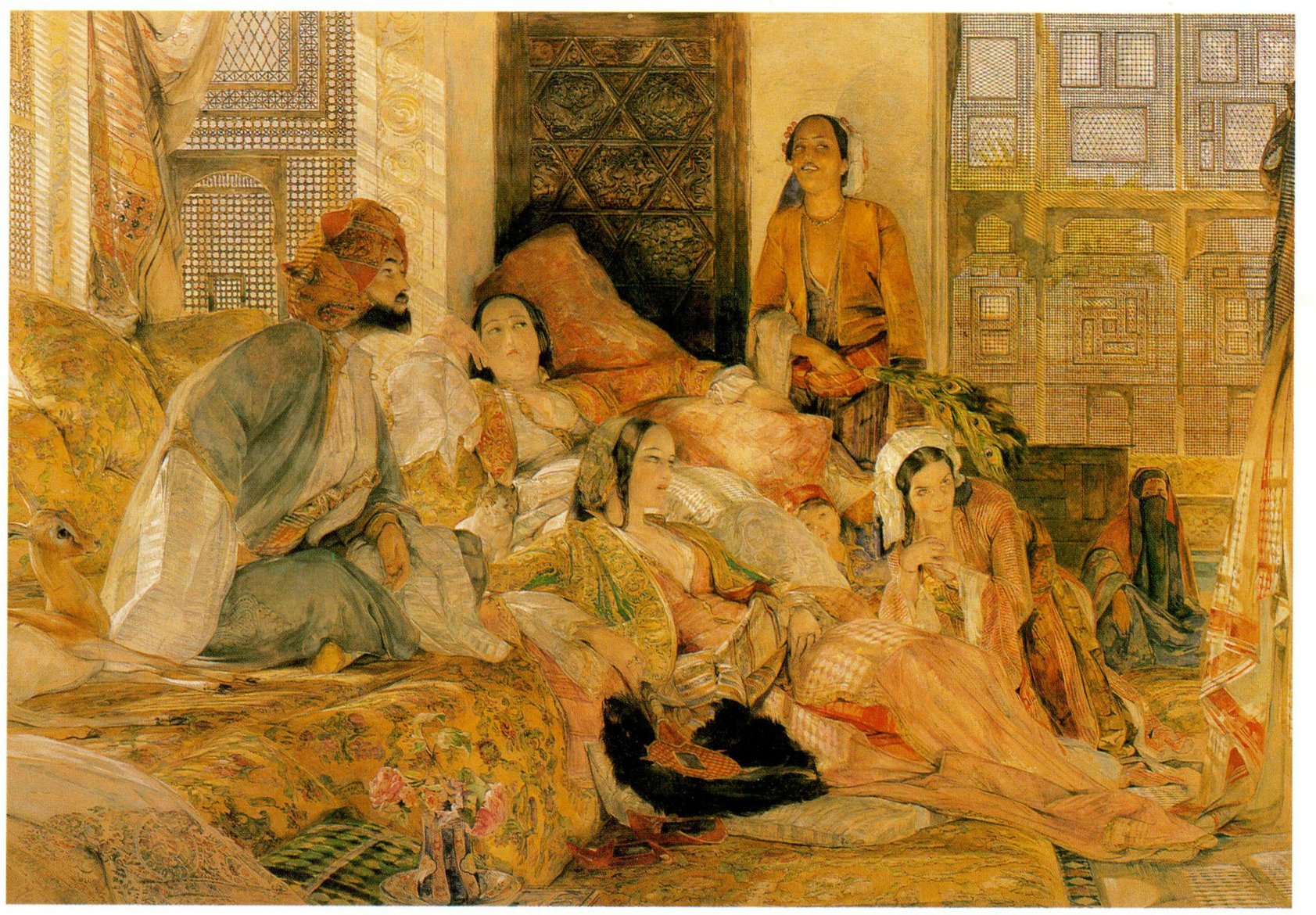

101 J.F. Lewis The Hhareem

102 William Henry Hunt Slumber

Apart from the truths which he quite simply believed were revealed directly to his inner sense by vision or trance, Blake’s thought was dominated by reverence for the past and in particular for certain literary monuments, of which the Bible was paramount. Even more than in illustrating the sometimes obscure symbolism of his own epics, he gave most satisfactory expression to his graphic skill in large cycles of designs which he prepared for the illustration of some of those works. Amongst such cycles are the illustrations to Young’s Night Thoughts, the designs for the Book of Job and, in the last years of his life, his illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy.

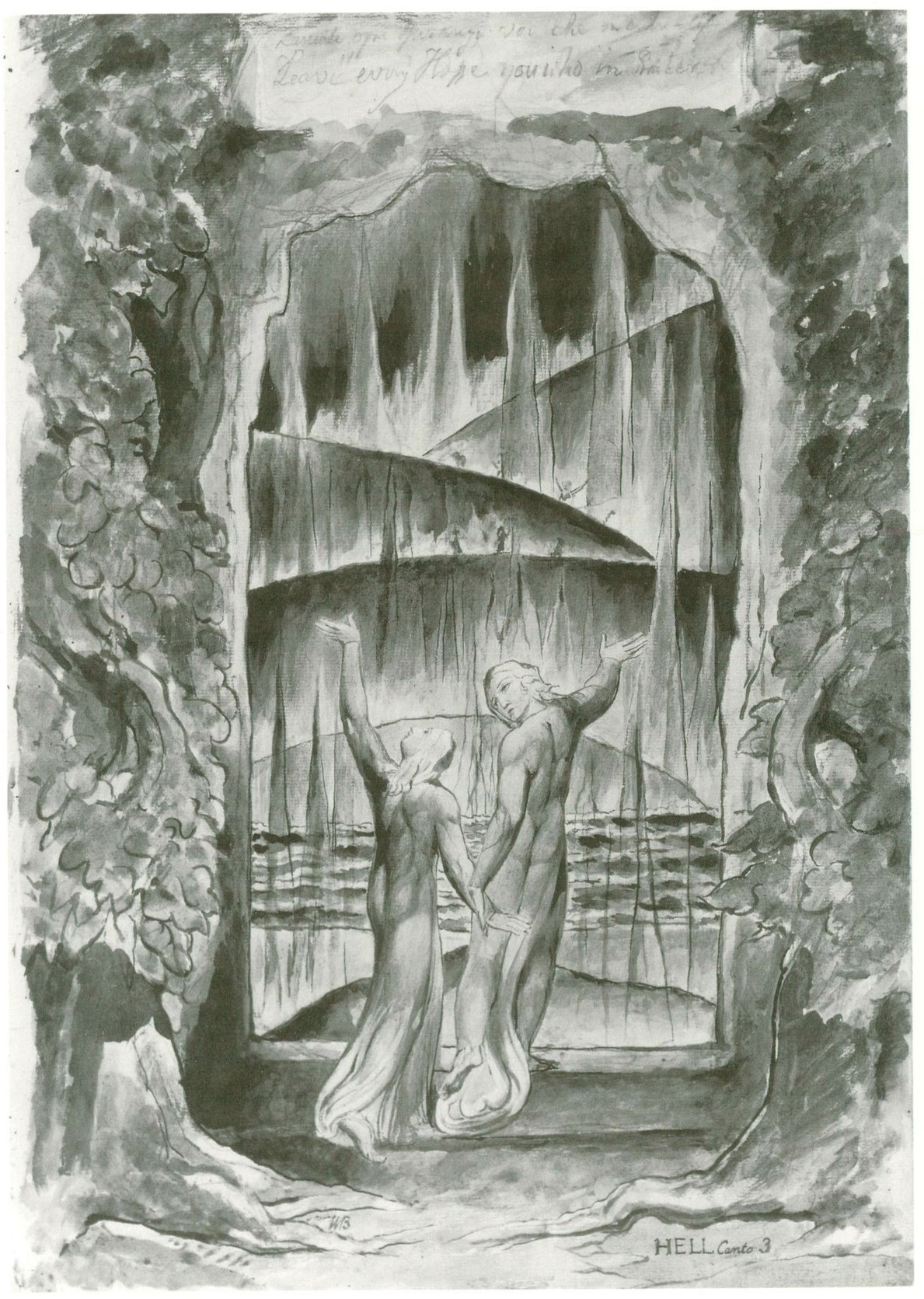

The illustrations for the Divine Comedy display his imagination at its grandest and most communicable. Here, as in the illustrations to Thornton’s Virgil, the figures, gigantic and larger than human as they are, fit naturally into the Titanic and Tartarean background of Dante’s, and Blake’s, conceiving. The deceptively sylvan entrance to Hell is an ironic contrast to the scenes of horror which are to follow (Fig.89). In one of the few perfectly satisfying transmutations of literary works into pictures, Blake has made it possible for us to believe in both the horror and the pity of the Inferno; he has communicated the infinite purgation of Paolo and Francesca which causes Dante to swoon with grief beside his impassive guide.

In the last ten years of his life, thanks to a meeting with the young artist John Linnell, William Blake became the centre of a small group of young and like-minded men who venerated him and to whom he transmitted his wisdom. Through them he re-entered in due course the main stream of English art. Among the friends was John Varley, who, with his astrological predilections, was fascinated by Blake’s faculty of summoning visions, or visual hallucinations, as we should probably call them. But mention of Varley serves to recall that he was an artist whose supernormal or psychic gifts in life were not reflected in his art, in vivid contrast to Blake who had, as far as anyone can, the power of translating one dimension of experience into another.

These friends of Blake were – besides Linnell and Varley — Calvert, Richmond, Palmer and F.O. Finch. Of these Calvert made a few early idylls of a haunting poetry before devoting himself to a reconstruction of the Grecian mythology (Fig.90). Two disciples who are of more direct relevance in following the course of English watercolour are Finch and Samuel Palmer. Francis Oliver Finch was of a calm, contemplative and poetical temperament. He said that Blake ‘struck him as a new kind of man, wholly original, and in all things’, and Finch’s own bent towards a mystical outlook is shown by his adhesion to the doctrines of Swedenborg. He was one of the pupils to whom Varley taught the craft of watercolour without suffocating their own original outlook. There is no direct resemblance between Finch’s style and the work of Blake; the influence of the latter is rather to be traced in a certain suffused lyricism. Finch almost entirely creates in terms of the ideal landscape compositions whose derivation from Italian practice has been described. He gives a new melancholy and a new nostalgia to the forms used by George Barret, junior, whom he most closely resembles; and he is perhaps the last orthodox exponent in England of the landscape methods directly derived from Claude (Fig.91).

91 Francis Oliver Finch Evening: A Cemetery