When John Kennedy entered politics in 1946 as a candidate for Congress in Massachusetts’s Eleventh Congressional District, several of those close to him were not convinced that, given his total lack of campaigning experience, he would be able to survive in the state’s rough-and-tumble political arena. But he quickly proved them wrong. During one of his earliest campaign appearances, he was verbally accosted by a heckler who shouted, “Where do you live? New York? Palm Beach? Not Boston. You’re a god-damned carpetbagger.” Staring the heckler down, Kennedy replied, “Listen you bastard … nobody asked my address when I was on PT-109.” Facing another audience that had wildly cheered each of his rival candidates when they bragged about “coming up the hard way,” he introduced himself by saying, “I’m the one who didn’t come up the hard way.” He won that crowd over as well.

After serving three terms in Congress, Kennedy was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1952. On September 12, 1953, he married Jacqueline Bouvier. Soon afterward the back problems that had long plagued him intensified and he was forced to undergo two serious operations. It was while he was recuperating that he wrote the highly acclaimed Profiles in Courage. By that time, the handsome young Kennedy’s wit, charm, and magnetic speaking skills, combined with the way in which he and his attractive, elegant wife were increasingly becoming favorites of the media, had made him one of the Senate’s most popular members. So popular, in fact, that as the 1956 Democratic National Convention convened in Chicago, there was serious talk that he would be selected as the vice presidential nominee. It was a prospect that Kennedy embraced and he actively began to pursue the nomination. Then, to the surprise of the convention, presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson threw his choice of running mate open to the “free vote” of the delegates. Kennedy came tantalizingly close, but after three ballots, he was beaten by Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver.

His narrow defeat was a blessing in disguise, given that he wasn’t tainted by being part of the Democratic ticket that was soundly defeated that November. Yet his enormous television exposure at the convention propelled him, more than ever, into an attractive, promising national figure. And it gave him a thirst for an even higher goal. Told by a fellow senator that he would be a shoo-in for the next vice presidential nomination, Kennedy replied, “I’m not running for the vice-presidency anymore. I am running for the presidency.”

He began his campaign for the Democratic Party’s 1960 presidential nomination with a determination to do everything it took to gain what he now wanted most. But his party’s leading luminaries, convinced that he was neither old enough nor experienced enough, were not encouraging about his prospects in 1960. “Senator,” Harry Truman publicly asked, “are you certain that you are quite ready for the country, or that the country is ready for you in the role of President …? [We need] a man with the greatest possible maturity and experience. … May I urge you to be patient?” Eleanor Roosevelt, the party’s most influential woman, shared Truman’s concerns, often addressing Kennedy as “my dear boy.” It was an issue that remained with Kennedy throughout the nomination campaign with the usually gracious Hubert Humphrey publicly admonishing him to “grow up and stop acting like a boy,” and fellow hopeful Lyndon Johnson delighting in telling a joke about Kennedy’s good fortune in having received a glowing medical report—from his pediatrician.

Rather than be discouraged by the assaults on his youth, Kennedy became, if anything, even more energized in his pursuit of the nomination. Night and day, with Jacqueline constantly at his side, he never stopped shaking hands, greeting workers, visiting every locale, large or small, that he could reach. “I am the only candidate since 1924, when a West Virginian ran for the presidency,” he boasted, “who knows where Slab Fork is and has been there.”

On July 13, 1960, Kennedy received the Democratic Party’s nomination as its candidate for president. In his acceptance speech, he evoked the term “New Frontier” as a blueprint for the ways he intended to lead the nation aggressively into a new decade. The theme of the speech was one he repeated throughout his campaign, and one that was later echoed in a far more historic speech. “The New Frontier of which I speak,” he told the delegates, “is not a set of promises—it is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer the American people, but what I intend to ask of them.”

Then he took to the road again, campaigning even more intensely than he had in his quest for the nomination. Ignoring the back that never stopped aching, constantly losing and regaining his voice, he traveled more than seventy-five thousand miles in his campaign plane, the Caroline. By this time he had become not only a seasoned campaigner but also an astute one. And his wit, charm, and grasp of the issues were resonating with millions of voters. But there was one issue that would not go away, one so serious that it threatened to derail his candidacy. Kennedy was a Roman Catholic, and throughout the nation there were many who believed that if he was elected president, his major decisions would be dictated by the head of the Catholic Church, the pope.

For Kennedy, it was not a new issue. He had been forced to confront it throughout his nomination campaign and had dealt with it effectively. Speaking to a largely Protestant crowd in Morgantown, West Virginia, he stated, “Nobody asked me if I was a Catholic when I joined the United States Navy.” Then he asked, “Did forty million Americans lose their right to run for the presidency on the day they were baptized Catholics?” Gaining momentum he said of his brother Joe, “Nobody asked my brother if he was a Catholic or Protestant before he climbed into an American bomber plane to fly his last mission.”

He won the crowd over that day, but at the midway point in his election campaign, his Catholicism was, according to many inside and outside the Democratic Party, the single most important issue in the election. Fuel was added to the fire when influential Philadelphia clergyman Dr. Daniel Poling charged that when Kennedy was a congressman, he had, on orders from the church, refused to attend a dinner honoring four chaplains who had gone down with their ship during World War II. The issue became even more intensified when one of the nation’s best-known Protestant ministers, Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, publicly declared that he doubted whether any Catholic president could carry out his duties without being influenced by the Vatican.

Despite counsel to the contrary from some of his most influential advisers, an outraged Kennedy was convinced that he had to publicly respond. He got his chance when he was invited to address the religious issue by the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. On September 12, 1960, before three hundred ministers and more than a hundred spectators, he addressed the issue head-on. “I believe in an America,” he said, “where the separation of church and state is absolute—where no Catholic prelate would tell the President (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote.” He emphasized, “I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for President who also happens to be Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters—and the church does not speak for me.”

Following his speech, he was met with a barrage of questions, all of which he addressed effectively, including queries regarding Poling’s accusation. What Poling had not made public, Kennedy explained, was that he had been invited to the dinner honoring the chaplains as “a spokesman for his Roman Catholic faith.” This he could not do, Kennedy stated, since he had no credentials “to attend in the capacity in which I had been asked.” Watching both the speech and Kennedy’s response to the ministers’ questions on television, Sam Rayburn, the legendary Democratic Speaker of the House, who had been a tepid Kennedy supporter at best, shouted out, “By God, look at him—and listen to him! He’s eating ’em blood raw.” A few days later Rayburn went out of his way to tell a Texas crowd that John Kennedy was “the greatest Northern Democrat since Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

Kennedy’s speech to the Houston ministers had come little more than a month before Election Day. Given the effect it had on its huge television audience, it was a prime example of the way American politics were being changed forever by the new medium. Just two weeks later, another television event had an even greater impact on the election. More than seventy million people watched the first-ever televised presidential debate. When it began, the vast majority were far more familiar with Richard Nixon than John Kennedy. When it ended, they had been exposed to a Kennedy who appeared healthier, wittier, and more poised than his opponent. Most important, as Richard Reeves observed, Kennedy “looked as presidential as the man who had been Vice President for the past eight years.” Studies later found that of the four million people who made up their minds based on the first television debate, three million voted for Kennedy.

It was arguably the deciding factor in one of the closest elections in U.S. history. By a popular vote margin of one sixth of 1 percent of the nearly sixty-nine million votes cast, John Kennedy was chosen to lead the nation. Two months later, with eight inches of snow on the ground and the temperature well below freezing, he delivered an inaugural address that he had been revising since his election. “In the long history of the world,” he stated, “only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility—I welcome it.” Calling upon the American people to enlist in “a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself,” he reminded them of the sacrifices that would have to be made. “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

It was a short speech—at 1,355 words, it was only about half as long as the average inaugural address. But as Kennedy biographers Robert Dallek and Terry Golway wrote, “When it was over and the day’s commemorations of freedom were finished, those words lingered. They linger still.”

![]()

As instrumental as Kennedy’s PT-109 heroics were in setting the stage for his political career, it was, in the opinion of many political pundits, the national attention and acclaim he received from the publication of Profiles in Courage that truly set him on the road to the White House. In January 1955, he sent a proposal for a “small book on ‘Patterns of Political courage’ ” directly to Cass Canfield, the legendary president and chairman of Harper & Brothers. After Canfield indicated interest in the book and volunteered suggestions, Kennedy, who had considered profiling acts of courage by political leaders in various areas of government, responded by describing how he now believed it would be best to narrow his focus.

January 28, 1955

Palm Beach, Florida

Mr. Cass Canfield:

Chairman of the Board

Harper & Brothers

49 East 33rd Street

New York, New York

Dear Mr. Canfield:

Many thanks for your very kind wire and letter concerning my proposal for a small book on “Patterns of Political Courage.” I certainly appreciate your willing interest and helpful suggestions.

I agree with you wholeheartedly that each case history used should be considerably expanded, in order to establish more fully for the layman the historical contexts in which such events occurred and in order to heighten the dramatic interest by providing a fuller glimpse of the individuals involved, their background and their personalities. I am not certain, however, that I could expand each incident to a story of five to eight thousand words without losing in a mass of personal and historical detail the basic facts concerning the courageous deed which is the heart of the book. I believe that introductory and concluding chapters along the lines you mention can be worked out.

Meanwhile, I would submit this one additional thought—namely, to restrict the major examples to acts of political courage performed by United States Senators. It seems to me such a book might better hold together, and might present a more consistent theme—particularly when it is to be written by a United States Senator. Consequently, I had considered dropping the example of John Adams defending the British soldiers at the British Massacre (not to be confused with his son, John Quincy Adams, who resigned from the Senate in the first example cited in the present draft); and adding to the manuscript three additional examples of political courage by Senators—involving William Giles of Virginia, Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and Lucius Lamar of Mississippi. With these additions, I feel it would be more feasible to reach the length of forty to sixty thousand words that you suggest, without unduly burdening each story with detail. Unless you feel that restriction to Members of the Senate is too limited, I will proceed accordingly. In the concluding chapter, however, it is my intention to cite briefly many other examples of political courage—including those performed by non-Members of the Senate—including the John Adams story already mentioned, John Peter Altgeld, Sam Houston, Charles Evans Hughes, Robert Taft and others. I regret that the only example of recent times to be included is the brief mention of Taft (and his opposition to the Nuremberg trials); but I am unable to say whether we are too close in time to other examples for our political history to include them or whether this lack is due to a decline in the frequency of political courage in the Senate.

I intend to begin work on a complete book-length manuscript immediately, and I will be most appreciative of your further suggestions and assistance.

With every good wish, I am

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

From the moment Kennedy received a contract for the book and began to write it in earnest, the title of the volume became an issue of concern. Harper’s was not thrilled with “Patterns of Political Courage.” One of its top salesmen suggested “Patriots,” but Kennedy was not enamored with that. As he would throughout his political career, he sought the advice of those close to him. Typical was a letter he sent to his sister Eunice.

July 26, 1955

Mrs. Eunice Shriver

220 East Walton Place

Chicago, Illinois

Dear Eunice:

Would you and Sarge and your friends mull over the following suggested titles for the book and let me know as soon as possible which you think is the best:

1. Men of Courage

2. Eight were Courageous

3. Call the Roll

4. Profiles of Courage.

Sincerely,

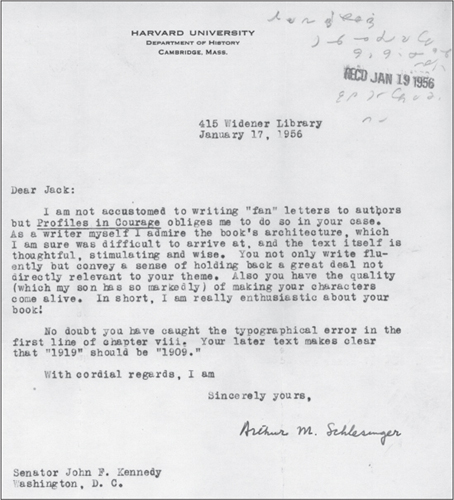

Published in 1956 with the finally agreed-upon title Profiles in Courage, Kennedy’s book immediately received widespread acclaim, and hundreds of laudatory letters poured into the senator’s office. One of the earliest was from the distinguished American historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr., who had known Kennedy at Harvard. In typical professorial manner, Schlesinger could not refrain from pointing out one of the errors in the book.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

CAMBRIDGE, MASS.

Kennedy’s second book, Profiles in Courage, earned a fan letter from Harvard professor Arthur Schlesinger Sr.

415 Widener Library

January 17, 1956

Dear Jack:

I am not accustomed to writing “fan” letters to authors but Profiles in Courage obliges me to do so in your case. As a writer myself I admire the book’s architecture, which I am sure was difficult to arrive at, and the text itself is thoughtful, stimulating and wise. You not only write fluently but convey a sense of holding back a great deal not directly relevant to your theme. Also you have the quality (which my son has so markedly) of making your characters come alive. In short, I am really enthusiastic about your book!

No doubt you have caught the typographical error in the first line of chapter viii. Your later text makes clear that “1919” should be “1909.”

With cordial regards, I am

Sincerely yours,

Arthur M. Schlesinger

An enormous success, Profiles in Courage remained on the bestseller list for ninety-five weeks, a period in which Kennedy’s daily mail included letters of praise from private citizens as well as well-known figures. In this letter, a Louisiana man issued a special challenge to the book’s author.

1104 Second Street

New Orleans, La.

June 7, 1956

Honorable John F. Kennedy

United States Senate

Washington, D.C.

Dear Senator Kennedy:

I have read your book “Profiles in Courage” and have enjoyed it very much. Candidly I think that it should be required reading for all Senators and Congressmen and for any person who might aspire to be a Congressman or a Senator. But why stop at that? Make it required reading for all politicians.

There is so much that a man with the courage of his convictions can do now adays. If such a person happens to be a senator such as you are, he can do a great deal.

For example, you could help to stem the definite trend towards socialism that is going on in this country today. Or you could help to cut down all of the unnecessary spending that is going on in Washington. This would include the vast amount of waste by the federal government as well as the special requests that the federal government spend money locally on projects that rightfully belong to the states. (This last would include spending in your own district, Massachusetts.) There are a multitude of other ways that a man with the courage of his convictions could make himself felt.

All of this leads up to my question. Perhaps a hundred years from now someone else will write another “Profiles in Courage.” Will the name of John F. Kennedy be included? Will you stand among the men you write about?

Very truly yours,

D.S. Binnings

Still highly popular today, Profiles in Courage has had at least sixty-five printings in various editions with total sales of more than three million copies. To the day he died, John Kennedy continued to receive letters acknowledging the value of what he had written, none more gratifying than the one he received in May 1957.

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK

NEW YORK 27, N.Y.

ADVISORY BOARD ON PULITZER PRIZES

May 7, 1957

Senator John F. Kennedy

Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C.

Dear Senator Kennedy:

I take very great pleasure in confirming the fact that the Trustees of Columbia University, on the nomination of the Advisory Board on the Pulitzer Prizes, have awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Biography or Autobiography, established under the will of the first Joseph Pulitzer, to you for “Profiles in Courage” for the year 1956.

In accordance with that award, I enclose the University’s check for $500 as tangible evidence to you of the selection of your work.

With renewed congratulations, I am

Sincerely yours,

John Hohenberg Secretary

The combination of the acclaim that Kennedy received from both his PT-109 heroics and for Profiles in Courage catapulted him into national prominence. As the 1956 Democratic Party’s national convention approached, many in the party believed he would be an attractive vice presidential candidate. As the following letter to his father indicates, Kennedy had no doubts as to who the party’s presidential candidate would be.

June 29, 1956

Honorable Joseph P. Kennedy

Villa Les Fal Eze

Eze S/Mer, A.M.

France

Dear Dad:

As you know, the authorization for the Vatican bill passed the Senate unanimously yesterday. I think the appropriation bill will be all right too.

The office has probably sent you the article which appeared in the New York Times containing Governor Ribicoff’s statement. I did not know he was going to say what he did, but when he keynoted the Democratic Convention at Worcester he had spoken to me about it. In the meantime he had John Bailey look into the matter further and I am enclosing a copy of John’s letter.

Governor Roberts seconded Ribicoff’s motion and Governor Hodges also indicated that it would be acceptable to him. The situation more or less rests there.

Arthur Schlesinger wrote to me yesterday and stated that he thought it should be done and that he was going to do everything that he possibly could. He is going to spend a month in Stevenson’s headquarters.

I have done nothing about it and do not plan to although if it looks worthwhile I may have George Smathers talk to some of the southern Governors. While I think the prospects are rather limited, it does seem of some use to have all of this churning up. If I don’t get it I can always tell them in the State that it was because of my vote on the farm bill.

We expect to get out of here in about three weeks and will then spend a couple weeks at the Cape before going to the Convention in Chicago. I expect to come to France with George Smathers right after the Convention.

Love,

P.S. Harriman was pretty well set back during the Governor’s Conference and it looks sure that Stevenson will either be nominated on the 2nd or 3rd ballot.

Kennedy would lose the 1956 vice presidential nomination to Estes Kefauver. But his strong showing at the party’s convention convinced him of the feasibility of a presidential run in the next election. When he began his bid for his party’s presidential nomination, Eleanor Roosevelt was not only the most influential woman in the Democratic Party, but also one of the most powerful in the world. Kennedy was well aware that even though Roosevelt was a staunch supporter of Adlai Stevenson for the presidency, he could not afford to alienate her. On November 7, 1958, a genuine crisis erupted when, on the nationwide ABC television program College News Conference the former First Lady made the serious accusation that Joseph Kennedy Sr. was attempting to “buy” the presidency for his son. Four days later, in what would be the beginning of a lengthy correspondence, Kennedy wrote to her, challenging her to prove her accusations.

December 11, 1958

PERSONAL

Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt

211 East 62nd Street

New York, New York

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt:

I note from the press that on last Sunday afternoon, December 7, on the ABC television program “College News Conference” you stated, among other things, that Senator Kennedy’s “father has been spending oodles of money all over the country and probably has a paid representative in every state by now.”

Because I know of your long fight against the injudicious use of false statements, rumors or innuendo as a means of injuring the reputation of an individual, I am certain that you are the victim of misinformation; and I am equally certain that you would want to ask your informant if he would be willing to name me one such representative or one such example of any spending by my father around the country on my behalf.

I await your answer, and that of your source, with great interest. Whatever other differences we may have had, I’m certain that we both regret this kind of political practice.

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

Kennedy responded swiftly—but carefully—to critical comments from liberal icon Eleanor Roosevelt.

Sixteen days later, Roosevelt replied, ending her letter by lecturing the senator.

MRS. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

202 FIFTY-SIXTH STREET WEST

NEW YORK 19, N.Y.

December 18, 1958

Dear Senator Kennedy:

If my comment is not true, I will gladly so state. I was told that your father said openly he would spend any money to make his son the first Catholic President of this country and many people as I travel about tell me of money spent by him in your behalf. This seems commonly accepted as a fact.

Building an organization is permissible but giving too lavishly may seem to indicate a desire to influence through money.

Very sincerely yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

Kennedy, according to colleagues, was appalled by Roosevelt’s reply. But he knew he had to tread softly with the person who led every public opinion poll in the United States as the most admired woman in the world. In a carefully worded letter that took him several days to construct and refine, he appealed to her “reputation for fairness” and asked her to “correct the record.”

Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt

202 56th Street West

New York 19, New York

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt:

Thank you for your letter of December 18, 1958. I am disappointed that you now seem to accept the view that simply because a rumor or allegation is repeated it becomes “commonly accepted as a fact.” It is particularly inexplicable to me inasmuch as, as I indicated in my last letter, my father has not spent any money around the country, and has no “paid representatives” for this purpose in any state of the union—nor has my father ever made the statement you attributed to him—and I am certain no evidence to the contrary has ever been presented to you.

I am aware, as you must be, that there are a good many people who fabricate rumors and engage in slander about any person in public life. But I have made it a point never to accept or repeat such statements unless I have some concrete evidence of their truth.

Since my letter to you, I assume you have requested your informants to furnish you with more than their gossip and speculation. If they have been unable to produce concrete evidence to support their charges or proof of the existence of at least one “paid representative” in one state of the union, I am confident you will, after your investigation, correct the record in a fair and gracious manner. This would be a greatly appreciated gesture on your part and it would be consistent with your reputation for fairness.

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

At the end of the first week of the new year, Roosevelt wrote back, telling Kennedy what she had done in response to his December 29 request.

MRS. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

202 FIFTY SIXTH STREET WEST

NEW YORK 19, N.Y.

January 6, 1959

Dear Senator Kennedy:

I am enclosing a copy of my column for tomorrow and as you will note I have given your statement as the fairest way to answer what are generally believed and stated beliefs in this country. People will, of course, never give names that would open them to liability.

I hope you will feel that I have handled the matter fairly.

Very sincerely yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

Roosevelt’s column did, in fact, contain Kennedy’s denial of the allegations that the former First Lady and others had made about his father trying to buy the election. But Kennedy was still not satisfied. As far as he was concerned, it did not go far enough. Carefully including an apology for burdening her with “a too lengthy correspondence,” he made his strongest statement in their exchange by asking her to state categorically that she had uncovered no evidence to indicate that Joseph Kennedy Sr. was attempting to buy the election.

January 10, 1959

Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt

202 56th Street West

New York 19, N.Y.

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt:

Thank you for sending me the copy of your column with the extract from my letter to you. Apparently there has been some misunderstanding of my reason for writing you.

While I appreciate your courtesy in printing my denial of the false rumors about my father and me, neither the article nor your letter to me deals with whether the rumors are true. In view of the seriousness of the charge, I had hoped that you would request your informants to give—not their own names—but the name of any “paid representative” of mine in any State of the Union. Or, if not the name, then mere evidence of his existence. I knew that your informants would not be able to provide such information because I have no paid representative.

Therefore, since the charges could not be substantiated to even a limited extent, it seemed to me that the fairest course of action would be for you to state that you had been unable to find evidence to justify the rumors.

You may feel that I am being overly sensitive about this issue. But when the record is as I have described it I feel that merely giving space to a denial that I have made leaves the original charge standing. The readers of your column and the listeners and viewers of the telecast of December 7 who do not have the benefit of our correspondence are forced to make their own judgments as to whether you or I am correct on the basis of your assertions and my denials.

I have continued what you may consider a too lengthy correspondence only because I am familiar with your long fight against the use of unsubstantiated charges and the notion that merely because they are repeated they attain a certain degree of credibility. If you feel that the matter was disposed of by your column, I certainly am prepared to let it rest on the basis of our correspondence.

Again I would like to express my appreciation for your courtesy in printing my denial of the charges.

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

Ten days later, in a letter notable for the former First Lady’s acknowledgment that because her family, like the Kennedys, was wealthy, it too had been subjected to rumors, Roosevelt adopted the most conciliatory tone she had yet taken.

MRS. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

202 FIFTY-SIXTH STREET WEST

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

January 20, 1959

Dear Senator Kennedy:

In reply to your letter of the 10th, my informants were just casual people in casual conversation. It would be impossible to get their names because for the most part I don’t even know them.

Maybe, like in the case of my family, you suffer from the mere fact that many people know your father and also know there is money in your family. We have always found somewhat similar things occur, and except for a few names I could not name the people in the case of my family.

I am quite willing to state what you decide but it does not seem to me as strong as your categorical denial. I have never said that my opposition to you was based on these rumors or that I believed them, but I could not deny what I knew nothing about. From now on I will say, when asked, that I have your assurance that the rumors are not true.

If you want another column, I will write it—just tell me.

Very sincerely yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

Relieved that, at least for the immediate future, he had beaten back the onslaught from the woman he could not afford to have as an enemy, Kennedy politely declined Roosevelt’s offer of another column, seizing the opportunity to open the door to a closer relationship.

January 22, 1959

Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt

202 Fifty Sixth Street West

New York 19, New York

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt:

Many, many thanks for your very gracious letter of January 20. I appreciate your assurance that you do not believe in these rumors and you understand how such matters arise. I would not want to ask you to write another column on this and I believe we can let it stand for the present.

I do hope that we have a chance to get together sometime in the future to discuss other matters, as I have indicated before.

Again many thanks for your consideration and courtesy, and with every good wish, I remain

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

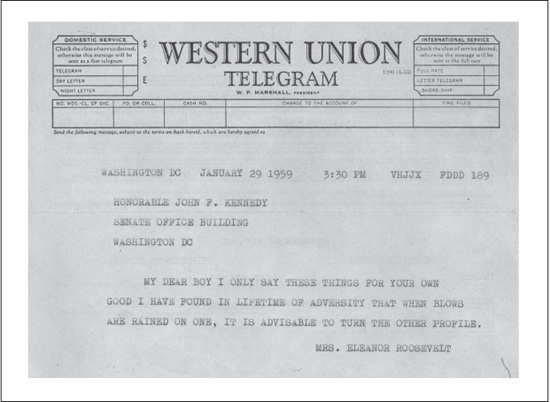

Their correspondence was still not quite over. True to her nature, Roosevelt was determined to have the final word. Nor, in a telegram, could she resist lecturing “my dear boy” one last time.

HONORABLE JOHN F KENNEDY

SENATE OFFICE BUILDING

WASHINGTON DC

MY DEAR BOY I ONLY SAY THESE THINGS

FOR YOUR OWN GOOD I HAVE FOUND IN

LIFETIME OF ADVERSITY THAT WHEN

BLOWS ARE RAINED ON ONE, IT IS

ADVISABLE TO TURN THE OTHER

PROFILE.

MRS. ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

Later in their correspondence Mrs. Roosevelt gave the youthful candidate some advice.

In his run for the presidency, it would be Kennedy’s good fortune to receive advice from such learned and important figures as economic and foreign expert John Kenneth Galbraith, who regarded Kennedy, a personal friend, to be the best choice to lead the nation in troubled and dangerous times. The following letter, written in early 1958, would be the first of what would become an ongoing correspondence between the two men.

February 4, 1958

Mr. J. K. Galbraith

Littauer Center 207

Cambridge 38, Massachusetts

Dear Ken:

Many thanks for letting me have a preview of your memorandum on “Democratic Foreign Policy and the Voter.” I have found this exercise in self-criticism congenial with many thoughts which I myself have had over the past months.

I quite agree with you that the emphasis of the Democratic Party, both in the broadsides issued by the Advisory Council and in Congressional speeches, has tended to magnify the military challenge to the point where equally legitimate economic and political progress have been obscured. It is apparent, too, that there are members of the party who seem to feel that the world stood still on January 20, 1953, and all we have to do is to pick up some loose threads that were broken then. It is clear also that, however tempting a target, the attacks on Mr. Dulles have been taken too often as a sum total of an alternative foreign policy—a new kind of devil theory of failure.

With these narrow horizons, which take little account of economic aid or the United Nations, the political lessons you draw seem none too harsh. For my own part, I intend to give special attention this year to developing some new policy toward the underdeveloped areas, a field in which I know you also have special interest and far greater competence.

I have sent to you a copy of the Progressive article I wrote on India, which will be followed up with further speeches.

With kind regards and every good wish,

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

From his Harvard days, Kennedy, a voracious reader, had kept closely abreast of world affairs, a trait that was essential to him as a candidate for president. He was particularly taken with the writings of two-time Pulitzer Prize winner George Kennan who, along with having written seminal articles and books about U.S. policy regarding the Soviet Union, had served as an American diplomat in various countries from 1926 to 1953.

February 13, 1956

Honorable George F. Kennan

7 Norton Street

Oxford, England

Dear Mr. Kennan:

Having had an opportunity to read in full your Reith lectures, I should like to convey to you my respect for their brilliance and stimulation and to commend you for the service you have performed by delivering them.

I have studied the lectures with care and find that their contents have become twisted and misrepresented in many of the criticisms made of them. Needless to say, there is nothing in these lectures or in your career of public service which justifies the personal criticisms that have been made.

I myself take a differing attitude toward several of the matters which you raised in these lectures—especially as regards the underdeveloped world—but it is most satisfying that there is at least one member of the “opposition” who is not only performing his critical duty but also providing a carefully formulated, comprehensive and brilliantly written set of alternative proposals and perspectives. You have directed our attention to the right questions and in a manner that allows us to test rigorously our current assumptions.

I am very pleased to learn that these lectures will soon be published in book form, almost simultaneously with the appearance of the second volume of your magistral study of U.S.-Soviet relations after World War I.

With kind regards and every good wish for your stay in Oxford,

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

Among those in the Democratic Party who had embraced the Kennedy candidacy early on was influential Connecticut governor Abraham Ribicoff. In a letter acknowledging that Kennedy was entering a period in which “important and crucial decisions” about his nomination campaign approach needed to be made, Ribicoff offered the following advice.

ABRAHAM RIBICOFF

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT

GOVERNOR’S RESIDENCE

December 16, 1959

Dear Jack:

Your vacation is well deserved. Being in the bosom of your family and exposed to the southern sun should give you the ease and relaxation you need. I know that this is the period of making up your mind about important and crucial decisions.

I have tried to watch your activities with a dispassionate eye even though I have been emotionally involved in your campaign. You have been absolutely superb during these past two years—busy, hectic, trying and provocative. You have gained in stature (opinion polls aside) and people sense this. Your speeches, both in content and in manner, have been of a nature to make a great impact on those who have listened to you. In casting up the score, you haven’t made a strategic mistake. Provocation there has been aplenty and you have had the constant patience to give the soft word when the natural inclination would have been to spit in someone’s eye.

Your travels have been so wide and you have seen so many people that as of now you, and only you, are the best judge of future moves concerning individuals, their word, and potential primaries. Jack, I don’t think that anyone can really advise you at this stage. You can tote up the score until you are “blue in the face” but many of these decisions cannot be resolved on an intellectual or scientific basis. You have that rare quality that too few people possess and which is an absolute must if one is going to be a leader—the ability to make a split second decision from the heart and the viscera as well as the mind and without benefit of commissions, advisers or well-wishers. Use your own heart and “feel” in the month ahead and I am confident that the results will be all that one could expect.

All my best to you, Jackie, your father and the other members of the family during this holiday season. May the coming year bring good health and success at the end of the rugged and often lonely road.

Sincerely,

Abe

In the fall of 1943, author and journalist John Hersey met Kennedy while he was in the New England Baptist Hospital recuperating from malaria and back surgery. Based on interviews with Kennedy and his crew, Hersey wrote an article for the New Yorker chronicling Kennedy’s actions in the aftermath of the sinking of PT-109. The article drew national attention, particularly after an abridged version was published in Reader’s Digest. In December 1959, U.S. News & World Report printed excerpts from Hersey’s article in an assessment of Kennedy’s presidential prospects. A month later, Hersey wrote what was obviously a good-natured protest letter to his friend Kennedy.

JOHN HERSEY

HULL’S HIGHWAY,

SOUTHPORT, CONN.,

JANUARY 22, 1960.

The Honorable John F. Kennedy,

U.S. Senate,

Washington, D.C.

Dear Jack:

A Hersey by-line over parts of the piece about your adventures in the Solomons, in U.S. News & World Report of December 21, 1959, came as a surprise to me, as David Lawrence, the editor, hadn’t checked with either me or The New Yorker for clearance before publication. Upon our inquiry, Lawrence reported that he had been given the piece by your office, and that it had carried no copyright notice. As a lawmaker and a Pulitzer-prize-winning author, Jack, you should be aware that that kind of doings is agin the statutes. Please cease and desist!

As for the rest of life, best wishes to you in your current endeavors.

Sincerely yours,

John Hersey

Kennedy’s reply to Hersey was also good-natured, although it did end on a serious note.

January 28, 1960

Mr. John Hersey

Hull’s Highway

Southport, Connecticut

Thank you for your gentle letter of protest. In return for absconding with the copyright rights I hereby deed to you all reprint rights of Why England Slept, and all returns therefrom.

I hope the next time you come to Washington you will call me, because I would like to have lunch with you. If you are not going to be down this way, I would like you to give me your thoughts as to the conduct of this campaign whenever you feel moved to do so. I would very much appreciate your help.

With warmest regards,

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

As the 1960 presidential election approached, Thomas E. Murray, a former member of the Atomic Energy Commission, wrote a letter to all the aspiring candidates asking them to state their position on nuclear testing. Kennedy’s reply gave him the opportunity to clearly articulate what his policies would be on one of the most hotly debated issues of the day.

Dear Mr. Murray:

Your thoughtful letter of September 6 is greatly appreciated.

I wholeheartedly concur in your opinion that the issue of nuclear weapon tests should not be exploited for partisan advantage. This subject, like all other public issues, is properly a matter for critical discussion and debate. But on this question—as on all other important issues—differences of opinion should be explored with responsible debate and with a full appreciation of the gravity of the question.

Your letter urges both presidential candidates to espouse the proposition that although the present ban on atmospheric tests should be retained, underground tests and tests in outer space should now be resumed, for the explicit purpose of developing nuclear weapons suitable for rational military purpose.

I do not agree that underground nuclear weapons tests should be resumed at this time. Should the American people choose me as their President, I would want to exhaust all reasonable opportunities to conclude an effective international agreement banning all tests—with effective international inspection and controls—before ordering a resumption of tests.

The Geneva Conference on Discontinuance of Nuclear Weapons Tests has been prolonged and generally discouraging. Even so, substantial progress has been made toward reaching agreement on some important phases of the problem.

The people of the United States, like millions of people all over the world, are anxiously hoping for an effective and realistic agreement outlawing nuclear tests—which means an agreement that is not dependent upon faith alone, but one enforceable through an effective system of international inspection controls.

I have always considered the conclusion of such an agreement of extreme importance not only to the people of the present nuclear powers, but for all mankind. This is true because new advances in technology have brought atomic weapons within reach of several additional nations.

For the United States to resume tests at this time might well result in a precipitate breakdown of the Geneva negotiations and a propaganda victory for the Soviets.

Under these circumstances I do not now recommend a resumption of testing. The question is not one of political courage. A man might courageously follow either course of action. The question is, which course of action is right.

It is possible that our negotiators, who have earnestly tried to negotiate a realistic and effective test ban, have exhausted every avenue of agreement, but since I have neither taken part in the negotiations nor had personal reports from the negotiators, who are not representatives chosen by me, I lack personal assurance of the futility of further discussions which alone would persuade me to urge the abandonment of so high an objective.

The Geneva Conference has been in progress, off and on, for almost 2 years. Despite the complexity of the subject, it should be possible within a reasonable period of time to find out whether the representatives of the Soviet Union are really prepared to enter into an effective test ban. If the Soviet Union still refused, after our earnest efforts, the world would then know where the responsibility lay.

Accordingly, it is my intention, if I am elected President, to pursue the following course of action

1. During my administration the United States will not be the first to begin nuclear tests in the world’s atmosphere to contaminate the air that all must breathe and thus endanger the lives of future generations.

2. If the present nuclear weapons test conference is still in progress when I am elected, I will direct vigorous negotiation, in accordance with my personal instructions on policy, in the hope of concluding a realistic and effective agreement.

3. Should the current Geneva Conference have been terminated before January 20, 1961, I will immediately thereafter invite Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union to participate in a new, and I would hope far more successful, conference on nuclear weapons test.

4. In either event, I intend to prescribe a reasonable but definite time limit within which to determine whether significant progress is being made.

At the beginning of the period, I would direct the Atomic Energy Commission to proceed with preliminary preparations for underground tests of the type in which radioactive substances would be forever sealed within the explosive cavity. If, within the period, the Russians remain unwilling to accept a realistic and effective agreement, then the world will know who is to blame. The prompt resumption of underground tests to develop peaceful uses of atomic energy, research in the field of seismic technology and improvement of nuclear weapons should then be considered, as may appear appropriate in the situation then existing.

5. I would also invite leading nations having industrial capacity for production of nuclear weapons to a conference to seek and, if possible, to agree upon means of international control of both the production and use of weapons grade fissionable material and also the production of nuclear weapons.

6. I will earnestly seek an overall disarmament agreement of which limitations upon nuclear weapons tests, weapons grade fissionable material, biological and chemical warfare agents will be an essential and integral part.

John F. Kennedy

On July 13, 1960, John Kennedy’s handling of what Governor Ribicoff had termed the “rugged and often lonely road” gained him the Democratic presidential nomination. Among the scores of congratulatory letters and telegrams he received was the following from one of the party’s most veteran and respected leaders, Senator Robert C. Byrd of Virginia.

WESTERN UNION

TELEGRAM

1960 JUL 15 PM 12 48

THE HONORABLE JOHN F. KENNEDY

HOTEL BILTMORE LOSA:

HAVING LEFT LOS ANGELES THIS MORNING AT 6 O’CLOCK, WHEN I WAS 135 MILES OUT OF LOS ANGELES, I LEARNED OF YOUR GRACIOUS INVITATION. I REGRET THAT INASMUCH AS I HAVE ALREADY STARTED HOMEWARD BY AUTOMOBILE AND MUST BE IN WASHINGTON TO START EUROPEAN TRIP NEXT WEEK, REGRETTABLY I WILL NOT BE ABLE TO BE WITH YOU TONIGHT. I CONGRATULATE YOU ON GREAT VICTORY AND I SHALL SUPPORT YOUR CANDIDACY ENTHUSIASTICALLY. I WANT EVEN NOW TO CONGRATULATE YOU ON WINNING IN NOVEMBER. IT WILL BE A PLEASURE TO WORK FOR AND SPEAK FOR THE ELECTION OF THE 35TH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES AND I SHALL DO ALL I CAN IN YOUR BEHALF IN WEST VIRGINIA. I AM DELIGHTED YOU WILL HAVE AS RUNNING MATE OUR ABLE MAJORITY LEADER, SENATOR LYNDON JOHNSON. I FEEL THIS ASSURES US MORE THAN EVER OF AN UNBEATABLE TICKET AND OF A SURE VICTORY THIS FALL.

ROBERT C BYRD USS.

Legendary harpist and comedian Harpo Marx sent his own note of congratulations on Kennedy’s achievement on July 14, 1960.

WESTERN UNION

TELEGRAM

SENATOR JOHN F KENNEDY

SPORTS ARENA LOSA

FIRST-CONGRATULATIONS. SECOND-DO YOU NEED A HARP PLAYER IN YOUR CABINET. THIRD-MY BEST TO YOUR MA AND PA-

HARPO MARX

By July 1960, John Kenneth Galbraith had become one of Kennedy’s most trusted advisers. The author of four dozen books and more than one thousand articles, Galbraith, during his lifetime, became the world’s best-known economist. Kennedy particularly enjoyed his quick wit. Most important, he valued Galbraith’s opinions on subjects that went well beyond economics. Days after Kennedy won the nomination, he received a letter from Galbraith offering advice on both his speaking style and the nature of his campaign speeches.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

July 16, 1960

Senator John F. Kennedy

Hyannis Port, Massachusetts

Dear Jack,

I hesitate to add to all the comment, liturgical and otherwise, you will have had on the acceptance speech. I listened to it here in Cambridge. But there are two matters which concern the future which I venture to bring up.

Let me say that I greatly approved the content. The New Frontier theme struck almost exactly the note that I had hoped for in my memorandum. So did the low key references to defense and Mr. K. [Khrushchev]. The reference to religion was good and indeed moving. By its nature much of the speech had to be an exercise in rhetoric, an art form in which I have never found it possible to practice, but it safely negotiated the delicate line that divides poetry from banality. I would hope that you would not need soon again to return to religion. You could succeed in making this an issue by speaking on it more frequently than is absolutely necessary. And your references to it are a license for others.

My suggestions concern construction of the speech itself—or rather those ahead. In the first place, your speech last night was essentially unfinished. It was badly in need of editing and polish. As a purely literary matter, the sentences could have been greatly smoothed. The images could have been much sharper and more vivid. Some superfluous words could have been drained out. The transitions could have been far smoother and more skillful. Your small transitions and changes of pace were insufficiently marked off from your major ones. This is partly a matter of speaking. But it is much more one of working into the text the warnings and signals (both to you and the audience) of the changes to come. Last night you were often well into the next sequence before the audience had realized that you had left the last. However, I do not wish to stress this point to the exclusion of others. The sharpening of images and allusions is also very important. All these matters not only make the speeches more effective. But they also make them much much easier to give. …

My next point concerns the nature of the speeches. It is evident that in straightforward exposition and argument you are superb. On the basis of your Los Angeles performance … I am prepared to argue that you have few masters in your time. When it comes to oratorical flights … you give a reasonable imitation of a bird with a broken wing. You do get off the ground but it’s wearing on the audience to keep wondering if you are going to stay up.

The solution here is simple. You cannot avoid these flights into space entirely—they are part of our political ritual. And maybe you could be less self-consciously awful in their performance although personally I would be sorry if you were. But the real answer is to keep this part of the speechmaking to the absolute minimum. My own guess is that people will welcome matter-of-fact and unpretentious discussion and anyhow that is what won you the primaries. In any case, I don’t think you have a choice …

Do have a good rest—this would seem to me more important than anything else.

Sincerely,

J.K. Galbraith

To his credit, Kennedy, who had already gained a reputation as a masterful speaker, took Galbraith’s constructive criticism most seriously. And soon he received a very different type of advice from political scientist Blair Clark.

Northeast Harbor, Maine

August 15, 1960

Dear Jack,

… As I told you in your office last week, Nixon’s performance the night he was nominated, as he sat on a sofa in the Blackstone with his wife, daughters, mother and talked of humility, home, God, fate, the little gray home in the west, was enormously effective political soap opera. To me, it was almost thrillingly repulsive, a shameless exploitation of self. You would never do this, nor could you. But I think you might consider using some things in your own background which permit people to identify with you as a person, not you as a political figure. As one example of what I mean, you come from an impressive political background; I think most intelligent people now look on the Democratic city “bosses” as essential links between the immigrants and the cold and careless political establishment of those days. If there were crooks among them, there were at least as many among the bankers and business men (please, let’s not talk about my great-great-grandpa Simon Cameron). What did your grandfather and his friends tell you, in the way of stories, when you were first getting into politics? My guess is that there is a rich vein to be mined here and that it would show your honorable ancestral origins and how they motivated you even as you rose above them to a more national role and to wider interests. I don’t think this sort of personal story is undignified or to be avoided; on the contrary, it’s the stuff of political parable and almost essential for the wide communication of ideas. Why leave all the corn to Nixon when your own hybrid brand could be so good? The above is just the beginning of a thought, but I think it’s right.

Please let me know if I can do anything.

Yours, as ever,

Blair

From the time he announced his presidential aspirations, Kennedy knew that both his youth and his relative lack of experience would be major campaign issues. One month after his nomination, he received valued advice on these subjects from what might have been considered an unlikely source—his former rival Adlai Stevenson.

ADLAI E. STEVENSON

135 SO. LASALLE STREET

CHICAGO

August 29, 1960

Dear Jack:

I have been too long in following up on our conversation about “age and experience.” This is probably a reflection of distaste for what is so obviously a phoney issue, at least on the merits.

The enclosed notes cover, I fear, only what is obvious. I have put them in as impersonal form as possible—in the unconscious desire, perhaps, to disassociate both of us from them:

Cordially yours,

Adlai

The “youth and inexperience” argument is an essentially false argument, significant only at the “image” level. This does not suggest that it can be disregarded. It means that it has to be dealt with as a “public impression” matter … it is reasonable to assume (i) that the “youth” element is much less significant than the “inexperience” element (particularly on a comparative basis); (ii) that the “inexperience” element has most of whatever significance it has in connection with the loose thinking about the business of “dealing with Khrushchev”; (iii) that this concern is felt more by women than by men.

Kennedy should not voluntarily take up this issue—as such—himself. Anything he says about it may appear defensive and accordingly contribute to the “image.”

Kennedy should neither be defensive about his age nor try to appear older than he is. He should not argue that William Pitt or Napoleon or others were younger. All such tactics suggest that he is trying to vindicate himself of a charge. Leave that to others.

If the issue comes up under circumstances requiring comment on it by Kennedy he should treat it as being a “youth” (rather than “inexperience”) issue. And youth is nothing to be ashamed of; in this campaign it is an asset. And the issue is irrelevant. The difference between 43 and 47 is inconsequential. If the Republicans are against young men, why did they nominate Nixon? Nixon was nominated for the Vice-Presidency at 39 and 43, and Dewey was nominated for the Presidency (in 1944) at 42. Bracketing Nixon in Kennedy’s age group makes it harder for him to ride the maturity vs. youth issue. …

The point can also be made that America, founded by men in their thirties or forties and still a young country, has today a special need for leadership which can understand and be able to communicate effectively with the new generation of leadership coming to power all over the world.

EXPERIENCE

The “experience” element in the already developing Republican argument is more serious.

It is something new, by the way, for the Republicans to proclaim that the man most experienced in government is the man best qualified to be President. The record of the past 30 years shows that they have consistently chosen Presidential candidates who had less experience than the Democrats. Eisenhower had less than Stevenson. Dewey had less than Truman and less than Roosevelt. Willkie and Landon had less than Roosevelt. Hoover had less than Smith. …

Kennedy’s own course of action should reflect his capacity for firm, thoughtful, courageous, decision-making. The public might be sensitive to any suggestion or petulance, argumentativeness, or either defensiveness or over-confidence. It will be important in the proposed television debates that obvious answers come tersely and directly but that the harder answers reflect full realization of the difficulties involved. …

To the extent that the “experience” issue relates less to actual past experience than to people’s hunches as to how the two candidates will react to future demands and crises, the campaign may present opportunities for aggressive leadership. There will be a Nixon equivalent of “I shall go to Korea”, if he can contrive one. This is not enough excuse for a Kennedy counterpart. But there is a basis even now for careful consideration whether the current crises (Congo, Cuba, disarmament, Russian rough stuff) warrant a dramatic but responsible proposal. If this can be done the “experience” issue will be won.

The importance of Kennedy’s public identification with people who perhaps symbolize “experience” is too obvious to warrant more than mention. What is perhaps less obvious is the equal importance of this being done not as a matter of “endorsement,” but rather as evidencing Kennedy’s ability to command essential resources.

And, finally, there is opportunity for effective ridicule in the low state to which we have fallen in the past eight years of “age and experience”—at home and abroad.

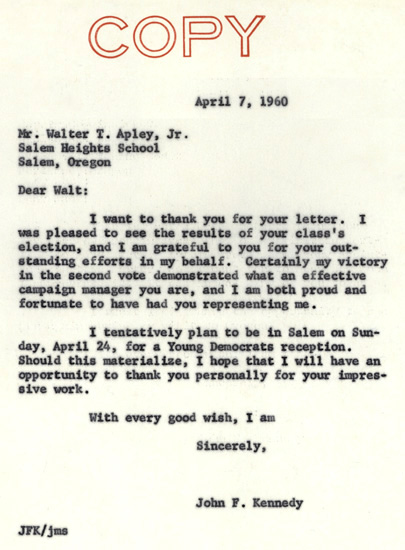

Well before he received the presidential nomination, Kennedy’s Senate office mailbags contained scores of letters from children. Among the most compelling of these was the one he received from a sixth grader informing him that in Walter Apley Jr., he had not only a supporter but an unsolicited campaign manager as well.

Salem Heights School

Salem, Oregon

February 29, 1960

Senator John Kennedy

c/o The Senate

Washington 6, D.C.

Dear Mr. Kennedy:

In view of the fact that the Presidential elections are being held this November, my sixth grade class decided to elect a President from the list of potential candidates.

The class first had a straw vote and the outcome was this:

Nixon |

17 |

Stevenson |

8 |

Kennedy |

2 |

Humphrey |

0 |

Johnson |

0 |

Rockefeller |

0 |

Symington |

0 |

Kennedy inspired young people as few American politicians ever had. As candidate and president he received thousands of letters from schoolchildren.

Our teacher, Mrs. Mendelson, asked for volunteers to head each candidate’s campaign, and I volunteered to head yours. We all were allowed four posters.

Two weeks later we had the arguments on who was the best man for President. After the arguments, we voted for a President.

Kennedy |

12 |

Nixon |

8 |

Stevenson |

7 |

Humphrey |

0 |

Johnson |

0 |

Rockefeller |

0 |

Symington |

0 |

As you and Mr. Nixon were fairly close, we decided to vote again between you two.

Kennedy |

15 |

Nixon |

12 |

Good luck in the primaries.

Your Salem Heights

Campaign Manager,

Walter T. Apley, Jr.

One can only imagine the pride that Kennedy’s response engendered in young Mr. Apley.

Mr. Walter T. Apley, Jr.

Salem Heights School

Salem, Oregon

Dear Walt:

I want to thank you for your letter. I was pleased to see the results of your class’s election, and I am grateful to you for your outstanding efforts in my behalf. Certainly my victory in the second vote demonstrated what an effective campaign manager you are, and I am both proud and fortunate to have had you representing me.

I tentatively plan to be in Salem on Sunday, April 24, for a Young Democrats reception. Should this materialize, I hope that I will have an opportunity to thank you personally for your impressive work.

With every good wish, I am

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

Letters from Senator Kennedy’s young admirers continued to pour in after he secured his party’s nomination for president—Kennedy inspired not just young campaign managers, but young poets as well. Among the most unique of the letters he received from schoolchildren was the following letter from Doreen Sapir in the form of a poem, in which the twelve-year-old creator demonstrated a surprising knowledge of events that had begun when she was only four years old.

July 17, 1960

Come on Kennedy, fight it out!

Let’s give Nixon a reason to pout.

Lash out against the Republican party,

Scorn their candidate good and hardy.

You saw what happened these last eight years,

Many were the causes for sorrow and tears,

In Cuba, for instance, the terror is shocking,

‘Tis not only Ike that Castro is mocking.

Where was our wonderful strength, and our spunk,

When our factories were stolen by that lousy Cuban skunk?

Perhaps Ike will say that the Communists bar us,

Well, things might have been a bit better, starting at Paris,

If he hadn’t let that U2 plane loose,

Khrushchev’s blunt rudeness would have no excuse.

He wouldn’t have found it so easy to give Castro his way—

Now “U.S. Aggression” is all they need say,

The Cuban situation is going very badly,

The Republicans have handled our country quite sadly.

For instance, the taxes have never been higher

There’s also a need for a good slum defier.

There’s plenty of proof as you probably know,

To show that Republican’s morales are low,

And so Kennedy, as you probably well see,

The odds are on Republicans, 1, 2, 3,

And in closing I just want to say,

Something which surely will brighten your day:

In our house, from basement, to front room, to attic,

Everyone is straight DEMOCRATIC

*SLOGAN—NIX ON NIXON*

By Doreen Sapir

3742 Silsly Rd.

Univ. Hts, 18, Ohio

12 years old

While young Cindy Baratz had not yet attained grammatical perfection, her letter to the candidate expressed clear reasons why Kennedy was her choice for president.

Thursday, October 23 1960

Dear Mr. Kennedy,

My Father was a Democratic and still is one for 10 years, but he never won.

I hope YOU are next President.

At school I not only say I vote you, but I tell all about the facts.

You want to build more school’s, more college’s, & Nixon says no, It’s to much money & You want to help the poor Peapole.

I think that you think nicely.

I am seven years old.

Sincerly, Yours

Miss Cindy Baratz

145 Gable Rd.

Paoli, Pa.

Throughout his life, John Kennedy regarded courage as the greatest of virtues. When, during his campaign, he learned of a Pennsylvania schoolgirl’s brave act on his behalf, he immediately wrote to her, expressing his gratitude:

Dear Judy:

I have learned of your persistence to remain in school despite the fact that the whole group was dismissed to hear Vice President Nixon speak.

I want to thank you for your devotion and spirit of independence at this time.

With every good wish, I am

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

Miss Judy Myers

743 South Front Street

Steelton, Pennsylvania

Kennedy could not help but be heartened by the expressions of support his candidacy received from the outset. But there was one issue that had also arisen from the moment he had announced his intention to run for the presidency, one so serious that it threatened his chances for election: Kennedy was Roman Catholic. Throughout the nation there were many who were convinced that a Catholic president would be bound to pledge greater allegiance to the Vatican and the church than to the United States Constitution. It was a concern clearly articulated in a letter sent to Kennedy by a Baptist minister.

The Honorable John Kennedy

United States Senate

Washington D.C.

Dear Senator Kennedy:

It is with an open mind that I am writing you, for it does not seem Christian to actively oppose something until one can be certain of the stand to be taken. As you are constantly reminded many of the American people are opposed to your running for the Presidency because of your faith. It is not easy to forget that even today in many parts of the world our Baptist missionaries are being persecuted by the Roman Catholic Church.

However, to me it is still an individual matter, and begins with the person not the church. You have my deepest sympathy in this situation. You cannot hope to please everyone, and as a minister I am more than aware of that.

Can you answer some questions for me? I am Moderator of a group of Baptist Churches in this part of the state, and I cannot actively support or oppose anything either among the many churches or my own church without knowing more than I do.

The state of Texas is predominately Baptist, and the Editor of the Baptist newspaper for the entire state and I have discussed the possibility of your candidacy for the Presidency in 1960. It would seem to be all but a “leadpipe cinch” that you will be the Democratic nominee.

Unless we Baptists know EXACTLY where you stand on major religious issues—we will be fighting your election down to the last inch.

If you would answer some questions that have been bothering me I would deeply appreciate it.

1. How do your beliefs coincide with the traditional stand of the country on separation of church and state?

2. Where do you stand on the appointment of an American ambassador to the Vatican?

3. In the event of pressure being applied where would your primary allegiance belong—to the Roman Catholic Church and the Vatican or to the United States and her people?

4. Would you advocate the use of public funds for Catholic or other sectarian schools? Would you actively oppose such usage of public funds?

Thank you very much for your gracious attention to this request, and I shall look forward to hearing from you at your earliest convenience.

Sincerely,

Mickey R. Johnston

Kennedy regarded Reverend Johnston’s letter as a welcome opportunity to articulate where he stood on the religious issue.

February 5, 1958

Rev. Mickey R. Johnston

Grace Temple Baptist Church

Henrietta, Texas

I am grateful to you for your letter of recent date and I welcome the opportunity to try to illustrate my position on the questions you have raised; for, like you, I feel that those of us who seek public office must be ready to express opinions on issues as we see them.

In the first place, I believe that the position of the Catholic Church with respect to the question of separation of church and state has been greatly distorted and is very much misunderstood in this country. As a matter of fact, I am quite convinced that there is no traditional or uniformly held view on the subject. For my own part, I thoroughly subscribe to the principles embodied in the Constitution on this point, particularly those contained in the First Amendment. It is my belief that the American Constitution wisely refrains from involvement with any organized religion, considering this most important but personal sphere not an area for government intervention. To this view I subscribe without reservation.

I do not favor the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Vatican, for I do not perceive any particular advantage to the United States in sending an ambassador there—and it is my belief that this should be the criterion in deciding on diplomatic relations.

I have no hesitancy in saying to you that in my public life I act according to my own conscience and on the basis of my own judgment, without reference to any other authority. As a public official I have no obligation to any private institution, religious or otherwise. My obligation is to the good of all.

On the question of aid to private schools, my position is also unequivocal. I support the Constitution without reservation, and as I understand its principles it forbids aid to private institutions. In this respect you may be interested to see the attached copy of a bill which I have recently introduced to provide Federal aid for the construction of public schools.

I appreciate the good faith in which your letter was written and I hope that my reply will help to clarify my position.

With every good wish,

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

Despite Kennedy’s continual explanations of his stance on religion, the issue would not go away. And, as the following letter and Kennedy’s reply to it reveal, anti-Catholic sentiment took many forms.

La Grange

North Carolina

May 13, 1960

Senator John P. Kennedy

Congressional Halls

Washington, D. C.

Dear Senator:

Can you and will you tell me why the Pre dominant Catholic Countries are mostly illiterate, illegitimates and so poverty stricken?

Please differentiate between the two major parties, Democrat and Republican.

Though 85, born June 12, 1975 [1875], I want to be able to vote intelligently and conscientiously.

Thank you for an early reply.

Sincerely yours,

Mrs. M. S. Richardson

June 10, 1960

Mrs. M. S. Richardson

La Grange

North Carolina

Dear Mrs. Richardson:

I am sorry I haven’t been able to reply to your letter before this. I believe that you will find that it is not possible to distinguish so-called Catholic countries on the basis of their wealth or social status. For instance, France is normally accepted as a Catholic country and I do not think that it has ever been charged that France is a nation of illiterates nor poverty stricken.

It is certainly true that in some countries where Catholics constitute a large portion of the population, stringent economic and social conditions do often exist but this can also be said of countries dominated by other Christian bodies or countries where the Christian church is in the distinct minority. It seems to me that poverty and illiteracy are related to other factors than the religion of the people.

There are many differences between the Republican and Democratic Parties but I would say that the Democratic Party has been characterized in modern times by a pressing concern for the welfare of all the people, particularly those who are less fortunate and less able to care for themselves. It has been Democrats who have spearheaded some of our most important social legislation such as the Social Security Act and at the present time, a comprehensive health insurance program for our elderly citizens.

Again, I am sorry for the delay in replying to your letter. I trust that these few comments will answer the questions which are in your mind.

With every good wish, I am

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

As the 1960 election year began, Kennedy sent out a lengthy, detailed statement to his most influential supporters, outlining what he regarded as the major issues facing the nation and how he intended to address them in the campaign. Typical of the replies he received was one from Hulan Jack, in which New York City’s powerful borough president could not refrain from reminding Kennedy of how important a role his religion was bound to play in the election.

PRESIDENT OF THE BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN

CITY OF NEW YORK

NEW YORK, N.Y.

HULAN E. JACK

PRESIDENT

Dear Jack:

I was delighted to receive your letter of December 28 with your enclosed statement of January 2, 1960, which I accept as the preamble of the beginning of your historic campaign. …

Your comprehensive statement clearly outlines the momentous issues facing this nation of destiny. Your courageous and forthright approach to the position of responsibility is refreshing. In maintaining America’s leadership in human dignity, the security of the individual, the jealous guardianship of our democratic processes and its expansion to give help, guidance, and leadership to mankind to build a world of peace and plenty for all to enjoy, we must aid in the economic development of the emerging nations.

It is my profound hope that our Democratic Party will recognize that the only sure road to winning in November is to have a fresh look in the person of our candidate for the high office of President. I personally think that our candidate must be young, with a dynamic as well as a warm personality, a good family man, with a deep religious background, a great appeal to the women’s vote, a thorough familiarity with the issues facing this nation, able to discuss them freely, willing to make decisions, a man who truly demonstrates leadership.

I would strongly deplore the injection by any of our citizens of the religious issue thereby denying all of the people of our great democratic society the talents of a noble and devoted public servant. I feel there is no room in our land for this kind of bigotry. I think we have demonstrated a long time ago that the cornerstone of our tradition is the principle of tolerance, understanding and equal trust. If these things are true then the right to worship as one pleases is inviolate, one’s faith in God is paramount, his religion is his right of choice and will have nothing to do with his oath of trust and allegiance to serve all of our citizens alike, irrespective of race, creed, color or origin.

If religious mistrust sweeps this nation then the clock has been turned back much to the regret of us all. We will then be impeding the larger objective which God has destined for this nation, to lead our unhappy world to the heights of human dignity, peace and plenty. The emerging nations look to us, the enslaved nations plead with us wearily for their deliverance. The underdeveloped nations want our productive know how and guidance to develop their economy.

Will we accept the challenge? I am positive we will: Now is the hour to make the profound decision. We need the man with the mostest. Let us not rob ourselves and mankind because of the evil of bias.

May God give us the vision and unselfishness to get behind a good image.

With best wishes for success and kind regards.

Sincerely yours,

Hulan E. Jack

President

Borough of Manhattan

As the presidential campaign gained momentum, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. (the son and Harvard colleague of the historian whose letter appeared above) became an increasingly important Kennedy adviser. After discussing the candidate’s approach to the religious issue with New York Times columnist James “Scotty” Reston and his wife, Schlesinger wrote to Kennedy with specific suggestions.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

UNIVERSITY 4-9710

ARTHUR SCHLESINGER, JR.

April 26, 1960

Dear Jack:

I had a talk yesterday with Scotty and Sally Reston about the religious question, and it seems worthwhile to pass along one or two points which emerged.

I told Scotty that, while I thought the issues he raised against your ASNE [American Society of Newspaper Editors] speech were legitimate, the effect of his column was to give the Catholic-bloc issue an importance out of all proportion to its place in the speech and that, in doing this, he failed badly to do justice to what seemed to me in the main an exceptionally clear and courageous statement. We then talked about the general problem for a while. I think I now know what troubles the Restons, and others who, like them, are generally well disposed toward you but are still unsatisfied by your treatment of the religious problem. They are impressed by your own clear declaration of independence on the relevant issues; but they remain troubled, I think, by what they feel to be an implication in your discussion that bigotry is essentially a Protestant monopoly. They would respond to an attack by you on all bigots and on all those who vote their religion, whether Protestant or Catholic. Their apprehension springs particularly, I believe, from the problems of small communities where Catholic voting blocs have caused difficult problems for the public schools.

In your ASNE speech you took steps to correct any impression that you felt that an anti-Kennedy vote was automatically an anti-Catholic vote. Of course you don’t believe that; and I think it is important to make this abundantly clear time and time again. I think that it would help to add to this a denunciation of religious bigotry in a way which would make it clear that you do not regard intolerance as an exclusively Protestant failing, that you recognize a tendency on the part of Catholics too to vote as a bloc, and that you condemn all tendencies to vote for as well as against candidates on religious grounds. (“I don’t want a single Catholic to vote for me for the reason that I am a Catholic any more than I want a single Protestant to vote against me for that reason.”)