As a U.S. Senator, John Kennedy had responded to a reporter’s question about his political ambitions by stating, “I suppose anybody in politics would like to be president. That is the center of the action, the mainspring, the wellspring, of the American system.” Now he was the man at the center, the first president of the United States to have been born in the twentieth century. The cold war that he had inherited required him to deal constantly with explosive issues throughout the world, issues so vital to the very future of people everywhere that even most of his domestic policies and programs were motivated by the struggle between democracy and the spread of communism. Several of these programs had been germinating well before his election.

Kennedy had long been disturbed by research showing that potential American military recruits were being rejected at an alarming rate as physically unfit for duty. He was equally concerned that each year more than twice the number of American children failed physical fitness tests as did European youngsters and, particularly, Russian young people. Shortly after his election, in an unprecedented move by a president-elect, he published an article in a national magazine describing a program he intended to introduce as soon as he entered the White House. Titled “The Soft American,” the Sports Illustrated article stressed “the importance of physical fitness as a foundation for the vigor and vitality of the activities of the nation.” Kennedy wrote, “Our struggle against aggressors throughout history has been won on the playgrounds and corner lots and fields of America.”

At the heart of the article was Kennedy’s belief that physical fitness was very much the business of the federal government. And with weeks of his taking office, the President’s Council on Physical Fitness launched a massive awareness campaign that included thousands of posters, brochures, pamphlets, television and radio kits, and exercise books all designed to make physical fitness, especially for schoolchildren, a national agenda. The emphasis on physical fitness was embraced even by the nation’s comic strip creators, seventeen of whom took up the subject, most notably Charles Schulz whose beloved character Snoopy encouraged youngsters to do their “daily dozen” exercises.

In an initial year in office that was marked by international setbacks and frustrations, the physical fitness program was one of Kennedy’s genuine successes. In December 1961, 50 percent more American students passed a national physical fitness test than had passed a year earlier. Equally encouraging, schools around the country were placing greater emphasis on physical fitness programs.

Also successful was another program that had been incubating in Kennedy’s mind well before his swearing-in. Just as he had been disturbed about how American youngsters lagged far behind their Russian counterparts in physical fitness, he was also concerned by the fact that while the Soviet Union “had hundreds of men and women, scientists, engineers, doctors, and nurses … prepared to spend their lives abroad in the service of world communism,” the United States had no such program. He had inspired the nation, particularly its young people, with his inaugural address. And he had entered the White House with plans for an ambitious project that would give life to his words “Ask what you can do for your country.” Two weeks before his election, in a speech at San Francisco’s Cow Palace, he had proposed “a peace corps of talented men and women” who would volunteer to devote themselves to the progress and peace of developing countries. Any doubt that Kennedy might have had of the appeal of such a program was removed when he received more than twenty-five thousand letters in response to his call. Under the direction of his brother-in-law R. Sargent Shriver, the Peace Corps, by providing thousands of American young people with the opportunity not only to aid millions in underdeveloped countries but also to serve as ambassadors of democracy and freedom, proved to be one of Kennedy’s most enduring legacies.

John Kennedy arguably delivered more quotable and compelling speeches than any other American president, aside from Abraham Lincoln. None was more surprising or seemingly more implausible than the address he made to Congress on May 25, 1961. It was in this speech that Kennedy announced that he would be holding his first face-to-face meeting with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev later that spring. But the address will always be remembered for the astounding proposal he laid before the legislators. “I believe,” he declared, “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” Congress, as alarmed as Kennedy at the possible military ramifications of the Russians having sent cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin rocketing into space to make a complete orbit of Earth, reacted to the president’s startling statement with thunderous applause. They even cheered when he told them that his “man on the moon” project would, over the next five years, require a budget of between $7 billion and $9 billion.

Despite congressional support, many were convinced that Kennedy’s goal could not be met. Yet within a year both Alan Shepard and Virgil Grissom were launched into space. Then, on February 20, 1962, came John Glenn’s historic 75,679-mile, three-orbital flight. In the weeks following Glenn’s triumph, Kennedy stepped up his rhetoric in support of the space program, which had now captured the imagination of the nation. His most eloquent articulation of the importance he placed on conquering this new frontier came in a September 12, 1962, speech at Rice University, in Houston, Texas. “We set sail on this new sea,” he stated, “because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be used for the progress of all people.”

Few would question that there was “new knowledge to be gained.” But it was another statement contained in the speech that best explained Kennedy’s strongest motivation. “No nation,” he declared, “which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in the race for space.” He meant “behind the Soviet Union.” Most revealing was the statement Kennedy made to NASA administrator James Webb. “Jim,” he told the man whose main goal was to make the United States preeminent in acquiring scientific knowledge that was to be gained from space exploration, “you don’t understand. I don’t give a damn about scientific knowledge. I just want to beat the Russians.”

Physical fitness, the Peace Corps, the space program—all in one way or another related to the communist threat. But Kennedy had also inherited an enormous challenge not related to issues abroad or in space. He had taken office at a time of tremendous racial turmoil at home. Throughout the South, African Americans and their supporters, committed to an unprecedented civil rights movement, were engaged in marches, sit-ins, demonstrations, boycotts, and other forms of protest in an effort to gain rights and opportunities long denied to them.

There was no question that Kennedy’s personal sympathies lay with those whose rights had been denied. And he abhorred the violence with which their efforts were often being met. But a host of political realities—his narrow election victory, his small margin in Congress, his desire not to alienate white Southern Democrats who chaired key congressional committees, and not least, his hope for reelection—combined to make him cautious. Of the millions of letters Kennedy received while president, most of the angriest and most embittered would be from black leaders tired of waiting for justice to be served, weary of lip service and empty promises, and outraged at the bombings, beatings, and other atrocities they were forced to endure.

More than two and a half years into his presidency, Kennedy, having finally lost patience with the continued acts of defiance of federal law by Southern governors and local officials, was compelled to act as decisively as the black leaders had been urging for so long. On June 11, 1963, the same day that Governor George Wallace attempted to block African American students from enrolling at the University of Alabama, Kennedy delivered a televised address to the nation on civil rights. Defining the civil rights crisis as a moral issue, he reminded the nation that “one hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.”

Kennedy then announced that he was submitting major civil rights legislation to Congress that would mandate African Americans receive “equal service in places … such as hotels, restaurants, and retail stores” and the right “to register to vote … without interference or fear of reprisal” and that would guarantee an end to segregation. The man who had been so reluctant to act at last put in motion the most far-reaching and effective civil rights legislation in the nation’s history.

![]()

Less than one month into his presidency, Kennedy received a most unexpected letter. It came from a Solomon Islander who had been instrumental in the rescue of the future American president and his PT-109 crew. A grateful Kennedy sent off a warm reply.

From the Solomon

Islands:

February 6, 1961

Dear Sir,

In my reverence and sense of your greatness I write to you. It is not fit that I should write to you but in my joy I send this letter. One of our ministers, Reverend E. C. Leadley, came and asked me, “Who rescued Mr. Kennedy?” And I replied, “I did.”

This is my joy that you are now President of the United States of America.

It was not in my strength that I and my friends were able to rescue you in the time of war, but in the strength of God we were able to help you.

The name of God be praised that I am well and in my joy

I send this loving letter to you, my friend in Christ,

it is good and I say “Thank you” that your farewell words to me

were those printed on the dime, “In God We Trust.”

God is our Hiding Place and our Saviour in the time of trouble and calm.

I am, your friend,

Biuku Gaza

Dear Biuku,

Reverend E. C. Leadley has recently sent me your very kind message, and I can’t tell you how delighted I was to know that you are well and prospering in your home so many thousands of miles away from Washington.

Like you, I am eternally grateful for the act of Divine Providence which brought me and my companions together with you and your friends who so valorously effected our rescue during time of war. Needless to say, I am deeply moved by your expressions and I hope that the new responsibilities which are mine may be exercised for the benefit of my own countrymen and the welfare of all of our brothers in Christ.

You will always have a special place in my mind and my heart, and I wish you and your people continued prosperity and good health.

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

Binku Gaza

Madon

Wana Wana Lagood

British Solomon Island Protectorate

As Kennedy prepared for his inauguration, Stewart Udall, whom Kennedy would appoint secretary of the interior, suggested that America’s great poet Robert Frost be invited to read one of his poems at the ceremonies. Kennedy, a longtime admirer of Frost and his work, readily agreed but not before reminding Udall, “You know that Robert Frost always steals any show he is part of.” The day after Frost received Kennedy’s telegram inviting him to participate, he sent his own telegram of acceptance.

IF YOU CAN BEAR AT YOUR AGE THE HONOR OF BEING MADE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, I OUGHT TO BE ABLE AT MY AGE TO BEAR THE HONOR OF TAKING SOME PART IN YOUR INAUGURATION. I MAY NOT BE EQUAL TO IT BUT I CAN ACCEPT IT FOR MY CAUSE—THE ARTS, POETRY, NOW FOR THE FIRST TIME TAKEN INTO THE AFFAIRS OF STATESMEN.

Having formed a bond with Frost, Kennedy, despite the demands of his office, would stay apprised of the poet’s activities.

March 8, 1961

Mr. Robert Frost

c/o American Friends of the Hebrew University

11 East 69th Street

New York 21, New York

I am delighted to learn of your recent appointment as the first Samuel Paley Lecturer in American Culture and Civilization at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. I know that your visit will provide the people of Israel with a rare cultural opportunity.

I wish you all success in your journey.

John F. Kennedy

One of the highlights of the Kennedy inauguration had been Frost’s recitation of one of his poems. It marked the first time a poet had ever taken part in a presidential inauguration. Although he had written a new poem titled “Dedication” for the occasion, Frost had trouble reading the faintly typed poem. Instead, he recited his poem “The Gift Outright” from memory. In March 1961, Kennedy received a letter from Hyde Cox, an old friend and editor of the Selected Prose of Robert Frost. In his letter, Cox thanked Kennedy both for his public recognition of Frost and for the unprecedented presidential attention to the arts.

CROW ISLAND

MANCHESTER

MASSACHUSETTS

March 15, 1961

Dear Jack,

Robert Frost has been here recently to help me celebrate my birthday, and together we signed this little book he promised to send your daughter—the book of his for which I wrote the foreword.

Because of my long and close friendship with him, and my friendly recollections of you, I feel that this is an appropriate moment for me to write the few personal words of congratulations that I have been tempted to send you before.

One of the things you are doing that touches me inevitably is your noticing the Arts—as they should be noticed; and I was especially touched by your recent, discerning recognition of Frost—so well expressed. He is a unique American asset.

But I do not mean to limit my praise of you to this friendship alone, or to the context of the Arts only. Believe me, you have—in more ways than these—the thoughtful best wishes and the admiration of an old acquaintance.

Very Sincerely,

Hyde Cox

Two months after receiving Cox’s letter, Kennedy wrote to Robert Frost thanking the poet for sending him a very special gift.

May 8, 1961

Dear Mr. Frost:

It was most gracious of you to inscribe the four copies of the special printing of your dedicatory poem and my inaugural address. I only regret that Mrs. Kennedy and I could not join the enthusiastic throng which heard your reading at the State Department Auditorium last week. I know that both Caroline and John will treasure this book in years to come.

It was a pity that you were unable to join us this morning when Commander Shepard was received and honored at the White House. I hope that you have had a good stay here in Washington and will be back with us soon again.

With every best wish,

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

Mr. Robert Frost

35 Brewster Street

Cambridge, Massachusetts

The Kennedy/Frost relationship would develop into one of great warmth and mutual admiration. So much so that, despite the poet’s age, in July 1962, Kennedy wrote to Frost asking him to undertake a special mission on behalf of the United States.

July 20, 1962

Dear Mr. Frost:

I have been informed by Secretary Rusk that the Soviet Union has expressed warm interest in the idea of an exchange of visits between two eminent American and Soviet poets, and your name has been mentioned as the logical American poet to initiate this exchange.

Ambassador Dobrynin has indicated that the Soviet Union would like to send the well-known Soviet poet, Alexander Tvardovsky, to our country as their part of this special exchange proposal.

Our great literary men are the ultimate custodians of the spirit and genius of a people, and it is my feeling that such an exchange of visits at this time would do much to enlarge the area of understanding between the people of the United States and the people of the Soviet Union.

I hope that you can represent the United States on this special mission. If you can accept this assignment please let me know, and I will have the State Department people contact you with regard to the plans and details.

Sincerely,

John Kennedy

Mr. Robert Frost

Ripton

Vermont

On the eve of his departure, Frost wrote to Kennedy expressing his feelings as only the already legendary Frost could do.

July 24, 1962

My dear Mr. President:

How grand for you to think of me this way and how like you to take the chance of sending anyone like me over there affinatizing with the Russians. You must know a lot about me besides my rank from my poems but think how the professors interpret the poems! I am almost as full of politics and history as you are. I like to tell the story of the mere sailor boy from upstate New York who by favor of his captain and the American consul at St. Petersburg got to see the Czar in St. Petersburg with the gift in his hand of an acorn that fell from a tree that stood by the house of George Washington. That was in the 1830’s when proud young Americans were equal to anything. He said to the Czar, “Washington was a great ruler and you’re a great ruler and I thought you might like to plant the acorn with me by your palace.” And so he did. I have been having a lot of historical parallels lately: a big one between Caesar’s imperial democracy that made so many millions equal under arbitrary power and the Russian democracy. Ours is a more Senatorial democracy like the Republic of Rome. I have thought I saw the Russians and the American democracies drawing together, theirs easing down from a kind of abstract severity to taking less and less care of the masses: ours creeping up to taking more and more care of the masses as they grew innumerable. I see us becoming the two great powers of the modern world in noble rivalry while a third power of United Germany, France, and Italy, the common market, looks on as an expanded polyglot Switzerland.

I shall be reading poems chiefly over there but I shall be talking some where I read and you may be sure I won’t be talking just literature. I’m the kind of Democrat that will reason. You must know my admiration for your “Profiles”. I am frightened by this big undertaking but I was more frightened at your Inauguration. I am glad Stewart will be along to take care of me. He has been a good influence in my life. And Fred Adams of the Morgan Library. I had a very good talk with Anatoly Dubrynin in Washington last May. You probably know that my Adams House at Harvard has an oil portrait of one of our old boys, Jack Reed, which nobody has succeeded in making us take down.

Kennedy and poet Robert Frost, who read at his inauguration, had a warm correspondence. Here Frost replies to an unusual invitation from the president.

Forgive the long letter. I don’t write letters but you have stirred my imagination and I have been interested in Russia as a power ever since Rurik came to Novgorod; and these are my credentials. I could go on with them like this to make the picture complete: about the English-speaking world of England, Ireland, Canada, and Australia, New Zealand and Us versus the Russian-speaking world for the next century or so, mostly a stand-off but now and then a showdown to test our mettle. The rest of the world would be Asia and Africa more or less negligible for the time being though it needn’t be too openly declared. Much of this would be the better for not being declared openly but kept always in the back of our minds in all our dilpomatic and other relations. I am describing not so much what ought to be but what is and will be—reporting and prophesying. This is the way we are one world, as you put it, of independent nations interdependent.—The separateness of the parts as important as the connection of the parts.

Great times to be alive, aren’t they?

Sincerely yours

Robert Frost

The Kennedy presidency was little more than three months old when the Peace Corps was officially approved by Congress. Shortly afterward, Kennedy received a letter from one of the new organization’s officials containing both welcome news and an important request.

May 16, 1961

Dear Mr. President:

You will be pleased to know that as of last night over 7,700 young men and women have answered your call as to what they can do for their country. Many of the letters and questionnaires from the applicants show that they have given a great deal of thought to their decision to join the Peace Corps since, as they say, it will change the whole pattern of their careers.

Mr. Wiggins asked me to speak to you about the attached letter which he would like to send out under your signature. The letter will be sent this week to the 7,700 Peace Corps candidates who have submitted questionnaires. The Peace Corps recruitment people are very encouraged by the large number of qualified applicants, but they fear that there may be some difficulty in making certain that they come to the examinations. Apparently a large number of students include college graduates and even postgraduate students. Most important of all there are many engineers, public health specialists and agricultural specialists etc.

Since Mr. Shriver has had good results on his recent trip, it is important that the Peace Corps have a large supply of applicants.

It is thought that a personal letter from you would certainly add to the enthusiasm of this group to sacrifice their time and efforts to the Peace Corps projects. Also it would be a worthwhile means of stimulating public interest.

Sincerely,

Deirdre Henderson

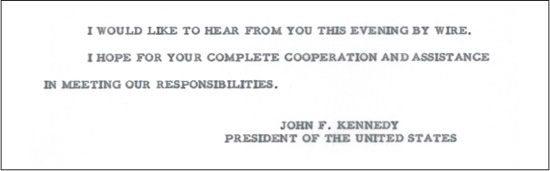

Kennedy responded to Ms. Henderson’s request the same day he received it, taking the opportunity to articulate to Peace Corps volunteers both the challenges they would face and the rewards they would receive.

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

May 22, 1961

Dear Peace Corps Volunteer:

I want to congratulate you for being among the first group to volunteer for service in the Peace Corps. As you know, you are now eligible to take the Peace Corps Entrance Examination on May 27 or June 5.

Nations in Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa have already indicated their interest in having Peace Corps Volunteers serve with them. In the months ahead agreements with these nations will be concluded and Peace Corps projects announced. Once you qualify as a Volunteer you will be eligible for these undertakings.

As a Volunteer you will be called upon to exercise your skill or talent under difficult and unusual circumstances. The work will be hard and it may be hazardous. But, when your assignment is completed, you will have earned the respect and admiration of all Americans for having helped the free world in a time of need. You will have made a personal contribution to the cause of world peace and understanding.

I wish you the best of luck in your Peace Corps tests.

Sincerely

John Kennedy

Among the scores of letters that the White House received from Peace Corps volunteers in the field and their relatives, one of the most poignant was in response to a condolence letter Kennedy had written to a couple whose son had suffered a fatal illness while serving in Colombia.

West Plains, Mo.

June 2, 1962

Dear President Kennedy,

As humbly and sincerely as we know how we want to thank you for your letter concerning our David.

David hated war and had a driving passion for peace. In an early letter to us from Colombia he stated, “I had rather lose my life trying to help someone than to have to lose it looking down a gun barrel at them.” David felt that the Peace Corps was the answer and there will never be a more loyal member.

Before David was born I prayed that my child would be a blessing to humanity. I believe God answered my prayer and I am grateful that through you and your program he had an opportunity to serve.

Be assured of our prayers, that you may look to God as you meet the great responsibilities that are yours today. Also for your precious little Son that he may live and love and serve as our David.

Sincerely yours,

Mr. and Mrs. R. L. Crozier

From the beginning, Kennedy had envisioned Peace Corps volunteers becoming American ambassadors of good will. By its third year of operations, the Peace Corps was meeting this goal.

PEACE CORPS

WASHINGTON 25, D.C.

February 13, 1963

[President Kennedy:]

I thought you might be interested in seeing this statement by Monsignor J.J. Salcedo, member of the Board of Directors of the Inter-American Literacy Foundation and Director General of the Accion Cultural Popular in Bogota, Colombia.

The history of humanity will record the young people of the Peace Corps as heroes. Their admirable sacrifices, their conviction, the generosity they are showing, are the best thing you are doing today for the good name of the great American people. But the worth of their actions is not in the roads, houses or bridges they are building (their work is mainly manual), but in the heroic lesson they are giving of true friendship. In the words of the Gospel: “Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (St. John, XV, 13).

“These young people are conquering the hearts of our people by means of their example, their work, their true love for the people.”

Robert Sargent Shriver, Jr.

In his August 13, 1963, Progress Report by the President on Physical Fitness, Kennedy made special mention of the fact that, thanks to the program that he and his administration had initiated, national awareness of the importance of staying fit was increasingly being reflected in the White House mail, where, according to Kennedy, “fitness is one of the main subjects of correspondence by young and old alike.” Among the letters Kennedy cited was one from a Brooklyn schoolgirl who wrote, “I am happy about your Physical Fitness Plan. … I turn cartwheels every chance I get. My parents are going out of their minds because I am always on my hands instead of my feet.” A twelve-year-old Pennsylvania boy, Kennedy reported, had written him stating, “I have took to mind what you said about youth physical fitness. I not only take gym in school, but I set aside an hour each day to have my own gym.”

Two letters in particular obviously amused the president. “Dear President Kennedy,” one youngster informed him, “I have walked 8 miles and I was thirsty.” “Dear sir,” wrote another, “would you please send me a sample of your physical fitness.” Of special note, Kennedy stated, was a letter he had received from a student in a U.S. Army school in Munich, Germany. “The purpose of my writing,” the young person explained, “is to congratulate you on your physical fitness program. All the students in my class take part in the program with great interest. Through the program, we are developing an interest in fair play with each other. The responsibility through our training gives us great pride and an understanding of our responsibility as Americans.”

Not all the letters Kennedy received, however, unreservedly praised the program. Young Gladys McPherson not only pointed out what she regarded as a serious problem, but she also offered a solution.

1023 Berwick

Pontiac, Mich.

March 14, 1963

Dear Mr. Kennedy,

Your physical fitness program is in full swing and a very fine idea, except for one hitch. How can women and teenage girls be physically fit with deformed feet? It is impossible to find round toe, flat heel shoes to fit sub-teens in women’s sizes, and difficult to find wedge or high heels with round toes. I’m sure you don’t expect the army or marines to hike fifty miles in pointed toes, but even gym shoes and house slippers for women are pointed.

I have written letters to newspapers and shoe manufacturers without success. But the solution is simple for you. Please convince Mrs. Kennedy to buy and wear in public round toe shoes, and every style conscious woman will demand the manufacturers make them.

Please, Mr. President, do this favor for the women of America to whom God gave rounded feet instead of pointed ones. We have suffered for a long time.

Respectfully yours,

Gladys D. McPherson

Another young woman, in sentiments well ahead of her time, described what she saw as another shortcoming of the physical fitness program.

It is a state law for all schools to have a Physical Fitness Program. We have a very fine gym but we girls are not about to use it for that purpose. The boys have many activities such as football, basketball, and etc. But we girls run around flabby! If we say anything to the Principal about the girls having a Program of any sort, he tells [us] to go home and do our own exercises. But Mr. President it is not fair to us girls because we want to do it as a group, not as individuals. The boys use the gym and we want to use it too.

In his letter, Richard Millington informed Kennedy of a problem that, in his opinion, threatened the success of the entire program.

Sacramento, Calif.

February 11, 1963

Dear President Kennedy,

I would like to know why, in this age of stress on physical fitness, there are still paunchy teachers around. These teachers are supposed to be good examples to us poor, disgusted kids. We kids do the exercise the teachers tell us, while the teachers stand around talking to other teachers. How are we supposed to believe exercises are worth it if the teachers don’t seem to be interested?

I move that a new law be passed that requires teachers to keep themselves in the pink too. Thank you for your attention and please reply soon.

Sincerely yours,

Richard Millington

P.S. Even some of the Scoutmasters have midriff bulge.

Of all the letters that the physical fitness program elicited, it is difficult to imagine one that Kennedy welcomed more than following from nine-year-old Jack Chase.

Terrance, California

Mar. 3, 1963

Pennsylvania Ave.

The White House

Washington, D.C.

Dear President Kennedy:

I know you are a very busy man but I wanted to tell you what a wonderful President I think you are.

My teacher Mrs. Moneymaker, told us that you want all the children of America to be strong and healthy. You want us to do exercises every day to build up our bodies. Instead of riding a car to school you want us to walk. We should walk to the store, to the library and anyplace that is not too near and yet not too far.

I am going to do all these things because I know that a strong boy makes a strong man and a strong man makes a strong country.

Yours, truly,

Jack Chase

Age 9

The Soviet Union’s achievement in launching a man beyond Earth’s atmosphere signaled a race for space that became an integral part of the cold war. Although he received the news of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s accomplishment with far more concern than pleasure, Kennedy was quick to send Soviet chairman Nikita Khrushchev a congratulatory telegram.

WASHINGTON, APRIL 12, 1961, 1:24 P.M.

THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES SHARE WITH THE PEOPLE OF THE SOVIET UNION THEIR SATISFACTION FOR THE SAFE FLIGHT OF THE ASTRONAUT IN MAN’S FIRST VENTURE INTO SPACE. WE CONGRATULATE YOU AND THE SOVIET SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS WHO MADE THIS FEAT POSSIBLE. IT IS MY SINCERE DESIRE THAT IN THE CONTINUING QUEST FOR KNOWLEDGE OF OUTER SPACE OUR NATIONS CAN WORK TOGETHER TO OBTAIN THE GREATEST BENEFIT TO MANKIND.

JOHN F. KENNEDY

Kennedy’s real feelings and his real goal as far as space exploration was concerned were clearly revealed in a communiqué he sent to Vice President Lyndon Johnson eight days after Gagarin’s flight.

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

April 20, 1961

In accordance with our conversation I would like for you as Chairman of the Space Council to be in charge of making an overall survey of where we stand in space.

1. Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to land on the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man. Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?

2. How much additional would it cost?

3. Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs. If not, why not? If not, will you make recommendations to me as to how work can be speeded up.

4. In building large boosters should we put out [our] emphasis on nuclear, chemical, or liquid fuel, or a combination of these three?

5. Are we making maximum effort? Are we achieving necessary results?

I have asked [science adviser] Jim Webb, Dr. [Jerome] Weisner, Secretary [of Defense Robert] McNamara and other responsible officials to cooperate with you fully. I would appreciate a report on this at the earliest possible moment.

After his orbital flight, John Glenn returned home to a hero’s welcome not seen since Charles Lindbergh had crossed the Atlantic. From leaders of free nations throughout the world came letters and telegrams commenting on the particular importance of the fact that it was an American achievement.

AACS/FEB 22 1962 VIA MACKAYRADIO

SCHOENRIED 100 22 185P

THE HONOURABLE JOHN F. KENNEDY

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON DC

IT IS WITH GREAT PLEASURE AND IMMENSE PRIDE WHICH I AM CERTAIN IS SHARED BY THE ENTIRE FREE WORLD THAT I EXTEND TO YOU AND TO THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRATULATIONS ON THE RESOUNDING SUCCESS OF THE ORBITAL SPACE FLIGHT OF COLONEL JOHN GLENN STOP COLONEL GLENNS PERSONAL COURAGE HAS WON UNIVERSAL ADMIRATION AND THE SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL COMPETENCE OF THE UNITED STATES THUS DEMONSTRATED GIVES ASSURANCE OF THE PEACEFUL EXPLORATION OF SPACE FOR THE BENEFIT OF MANKIND

RAINIER PRINCE OF MONACO

As the nation welcomed John Glenn into the ranks of its greatest heroes, many citizens wrote to Kennedy suggesting ways that the astronaut might be further utilized to give the United States a cold war advantage.

Hon. John F. Kennedy

President of the United States

White House

Washington, D.C.

My dear President:

May I humbly offer a suggestion to your Excellency?

Would it not be a splendid idea to appoint our famous Astronaut Col. John Glenn to be Ambassador of Good will to all Nations of the World that will want to know what is in outer space which Col. Glenn can explain so well?

This could inadvertently make the road for Khrushchev rockier.

Very truly yours,

Carl H. Peterson

As requests for personal appearances by John Glenn escalated, Kennedy had to decline one from the governor of Nebraska.

Dear Frank:

I am most grateful for your kind invitation to Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr., to visit your State, and I can assure you that he, too, is grateful for this invitation. As you may be informed by now, the decision has been made not to send Colonel Glenn or the other astronauts on any extended tour in this country or abroad even though many people would be delighted to see him and to demonstrate their pride in the achievements made possible by him and the Project Mercury team.

The United States manned space flight program managed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration will be pushed forward on the highest priority as it has been up to now, and each astronaut plays an important role as a result of his experience and training. Therefore, I feel this return to work is in the best interests of the program.

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

The Honorable Frank B. Morrison

The Governor of Nebraska

Lincoln, Nebraska

While the vast majority of letters that Kennedy received about the space program, particularly after Glenn’s flight, were highly positive, there were some that expressed concern over placing so high a priority on such an expensive endeavor. Among the most compelling was that written by thirteen-year-old Mary Lou Reitler.

January 19, 1962

R.F.D. #1

Delton, Michigan

Dear President Kennedy,

I am thirteen years old and I’m in the eighth grade. Please don’t throw my letter away until you’ve read what I have to say. Would you please answer me this one question? When God created the world, he sent man out to make a living with the tools he provided them with. They had to make their living on their own with what little they had. If he had wanted us to orbit the earth, reach the moon, or live on any of the planets, I believe he would have put us up there himself or he would have given us missiles etc. to get there. While our country is spending billions of dollars on things we can get along without, while many refugees and other people are starving or trying to make a decent living to support their families. I think it is all just a waste of time and money when many talents could be put to better use in many ways, such as making our world a better place to live in. We don’t really need space vehicles. I think our country should try to look out more for the welfare of its people so that we can be proud of the world we live in. At school they tell us that we study science so that we can make our world a better place to live in. But I don’t think we need outer space travel to prove or further the development of this idea. …

Sincerely,

Mary Lou Reitler

Despite the misgivings of those like young Ms. Reitler, John Glenn’s achievement provoked an overwhelming wave of support for the space program. A number of letters that came into the White House actually contained monetary donations to the effort. An Oregon state legislator and his wife sent in a donation of a surprising amount.

March 19, 1962

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Howard:

The President has asked me to thank you for your donation of $4.30 for the space program which you forwarded in your letter of March 3, 1962. Your interest in Colonel Glenn’s successful flight is sincerely appreciated. Your check will be forwarded to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for their use in the space programs under their jurisdiction.

Sincerely,

T.J. Reardon, Jr.

Special Assistant

to the President

The Honorable and Mrs. Norman R. Howard

Oregon House of Representatives

2504 S.E. 64th Street

Portland, Oregon

Kennedy had set the seemingly impossible goal of landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade. But following Glenn’s triumph and a number of technical breakthroughs, he asked NASA administrator James Webb to establish a 1967 target date for a lunar landing. Then, in the fall of 1963, after touring a number of NASA installations, he asked Webb to prepare a report analyzing the possibility of a 1966 landing.

Webb responded with a letter outlining the ways in which all the projects associated with a 1967 target date would have to be accelerated and listing the considerable additional costs that would be required in moving the target date up by a year. Webb concluded by stating that despite these considerable challenges, NASA was “prepared to place the manned lunar landing program on an all-out crash basis aimed at the 1966 target date if you should decide this is in the national interest.”

Only days after receiving Webb’s letter, Kennedy met with Webb and other top NASA officials and made it clear that he was all for a 1966 lunar landing. As far as the funds needed for an accelerated program, he told them that the money could be taken from certain NASA scientific projects that he felt could be delayed. Webb, however, was far from thrilled with that idea. Responding to Webb’s arguments that many of the scientific projects were essential to the manned moon landing and that preeminence in all of space was NASA’s true goal, Kennedy asked the NASA head to write him a “summary of our views on NASA’s priorities.”

NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE

ADMINISTRATION

WASHINGTON 25, D.C.

OFFICE OF THE ADMINISTRATOR

November 30, 1962

The President

The White House

Dear Mr. President:

At the close of our meeting on November 21, concerning possible acceleration of the manned lunar landing program, you requested that I describe for you the priority of this program in our over-all civilian space effort. This letter has been prepared by Dr. Dryden, Dr. Seamans, and myself to express our views on this vital question.

The objective of our national space program is to become pre-eminent in all important aspects of this endeavor and to conduct the program in such a manner that our emerging scientific, technological, and operational competence in space is clearly evident.

To be pre-eminent in space, we must conduct scientific investigations on a broad front. We must concurrently investigate geophysical phenomena about the earth, analyze the sun’s radiation and its effect on earth, explore the moon and the planets, make measurements in interplanetary space, and conduct astronomical measurements. …

Although the manned lunar landing requires major scientific and technological effort, it does not encompass all space science and technology, nor does it provide funds to support direct applications in meteorological and communications systems. Also, university research and many of our international projects are not phased with the manned lunar program, although they are extremely important to our future competence and posture in the world community. …

A broad-based space science program provides necessary support to the achievement of manned space flight leading to lunar landing. The successful launch and recovery of manned orbiting spacecraft in Project Mercury depended on knowledge of the pressure, temperature, density, and composition of the high atmosphere obtained from the nation’s previous scientific rocket and satellite program. Considerably more space science data are required for the Gemini and Apollo projects. At higher altitudes than Mercury, the spacecraft will approach the radiation belt through which man will travel to reach the moon. Intense radiation in this belt is a major hazard to the crew. Information on the radiation belt will determine the shielding requirements and the parking orbit that must be used on the way to the moon.

Once outside the radiation belt, on a flight to the moon, a manned spacecraft will be exposed to bursts of high speed protons released from time to time from flares on the sun. These bursts do not penetrate below the radiation belt because they are deflected by the earth’s magnetic field, but they are highly dangerous to man in interplanetary space.

The approach and safe landing of manned spacecraft on the moon will depend on more precise information on lunar gravity and topography. In addition, knowledge of the bearing strength and roughness of the landing site is of crucial importance, lest the landing module topple or sink into the lunar surface. …

In summarizing the views which are held by Dr. Dryden, Dr. Seamans, and myself, and which have guided our joint efforts to develop the National Space Program, I would emphasize that the manned lunar landing program, although of the highest national priority, will not by itself create the pre-eminent position we seek. The present interest of the United States in terms of our scientific posture and increasing prestige, and our future interest in terms of having an adequate scientific and technological base for space activities beyond the manned lunar landing, demand that we pursue an adequate, well-balanced space program in all areas, including those not directly related to the manned lunar landing. We strongly believe that the United States will gain tangible benefits from such a total accumulation of basic scientific and technological data as well as from the greatly increased strength of our educational institutions. For these reasons, we believe it would not be in the nation’s long-range interest to cancel or drastically curtail on-going space science and technology development programs in order to increase the funding of the manned lunar landing program in fiscal year 1963. …

With much respect, believe me

Sincerely yours,

James E. Webb

Administrator

Webb’s letter proved persuasive. Finding himself in agreement with all of Webb’s arguments, Kennedy abandoned his push for an earlier lunar landing. In the all-too-brief remaining months of his presidency, he publicly proclaimed that America’s goal was to become preeminent in every area of the nation’s space program. Kennedy would not live to see an American land on the moon.

Although it seems contradictory to Kennedy’s passion for winning the battle with the Soviet Union for the conquest of space, Kennedy also expressed a determination to work with the Russians on joint space endeavors.

In 2011, thanks to the Freedom of Information Act requests, two communiqués written by Kennedy just days before he was killed were made available. In one, Kennedy ordered NASA administrator James Webb to develop a program of cooperation with the Soviet Union for both space exploration and lunar landings.

I would like you to assume personally the initiative and central responsibility within the Government for the development of a program of substantive cooperation with the Soviet Union in the field of outer space, including the development of specific technical proposals. I assume that you will work closely with the Department of State and other agencies as appropriate.

These proposals should be developed with a view to their possible discussion with the Soviet Union as a direct outcome of my September 20 proposal for broader cooperation between the United States and the USSR in outer space, including cooperation in lunar landing programs. All proposals or suggestions originating within the Government relating to this general subject will be referred to you for your consideration and evaluation.

In addition to developing substantive proposals, I suggest that you will assist the Secretary of State in exploring problems of procedure and timing connected with holding discussions with the Soviet Union and in proposing for my consideration the channels which would be most desirable from our point of view. In this connection the channel of contact developed by Dr. Dryden between NASA and the Soviet Academy of Science has been quite effective, and I believe that we should continue to utilize it as appropriate as a means of continuing the dialogue between the scientists of both countries.

I would like an interim report on the progress of our planning by December 15.

John F. Kennedy

In other correspondence, written the same day, Kennedy ordered the director of the CIA to release to him secret documents held within the agency concerning UFOs. “One of his concerns,” author William Lester, who succeeded in obtaining the communiqués, has stated, “was that a lot of these UFOs were being [reported] over the Soviet Union and he was very concerned that the Soviets might misinterpret these UFOs as U.S. aggression, believing that it was some of our technology.”

November 12, 1963

Director, Central Intelligence Agency

As I had discussed with you previously, I have initiated and have instructed James Webb to develop a program with the Soviet Union in joint space and lunar exploration. It would be very helpful if you would have the high threat cases reviewed with the purpose of identification of bona fide as opposed to classified CIA and USAF sources. It is important that we make a clear distinction between the knowns and unknowns in the event the Soviets try to mistake our extended cooperation as a cover for intelligence gathering of their defense and space program.

When this data has been sorted out, I would like you to arrange a program of data sharing with NASA where unknowns are a factor. This will help NASA mission directors in their defensive responsibilities.

I would like an interim report on this data review no later than February 1, 1964.

John F. Kennedy

It was not surprising that a president as popular as John Kennedy—who was forced to deal with issues more critical than those any American chief executive had ever before faced, and who, thanks to television, was seen by more people at one time than any other previous world leader—would receive a staggering number of letters on every conceivable subject from individuals from every walk of life.

Many of the letters that Kennedy would write as president would deal with some of the most thorny and dangerous issues with which any American president had ever had to contend. Others, like the one he sent to John Galbraith’s son on his birthday, would be characterized by the Kennedy wit.

January 26, 1961

Dear Jamie:

I understand that you were born in the last year of the last Democratic Administration and are now celebrating your ninth birthday in these first two weeks of mine. I hope that the long Republican years have not hurt you too much, that you will grow up to be at least as good a Democrat as your father but possibly of a more convenient size.

My best wishes for a happy birthday.

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

Master James Kenneth Galbraith

30 Francis Avenue

Cambridge 38, Massachusetts

Nelson Rockefeller was the governor of New York and one of the Republican Party’s leading candidates to oppose Kennedy when he ran for reelection in 1964. In November 1961, Rockefeller’s youngest son, Michael, disappeared while studying the Asmat tribe and its unique art in southern New Guinea. Despite an intense and prolonged search, the twenty-three-year-old Rockefeller was never found. Two weeks into the search, the grateful and still-hopeful governor wrote to Kennedy to thank him for his concern and assistance.

STATE OF NEW YORK

EXECUTIVE CHAMBER

ALBANYM

NELSON A. ROCKEFELLER

GOVERNOR

December 1, 1961

Dear Mr. President:

The deep human understanding which motivated your wire last week, at the time of Michael’s disappearance, with your offer of all possible assistance, is something I shall never forget, and is something for which I shall be eternally grateful to you.

Thanks importantly to your personal concern, no possible means of search was overlooked. The Department of State and Defense as well as CIA gave every assistance. The Department of Defense enlisted the full support of the Netherlands air and naval units to supplement the all-out effort of their civilian personnel, and also an Australian air and army helicopter unit which did a superb job. In addition, the Seventh Fleet, as well as the Air Force in Hawaii offered to send task forces. However, these latter two offers were declined with the deepest appreciation in view of the fact that every possible avenue of approach was being covered.

I would like to add that both the Dutch Catholic and American Protestant missionaries were uniquely kind and generous in their help.

While as yet no trace of Mike has been found, over 1,500 square miles of sea, 150 miles of coastline have been searched and all of the villages in the area have been visited. The search will continue in a jungle area of approximately 1,000 square miles, conducted by native Papuans, and I’m confident that if he was able to make the shore, he will be found.

With best wishes,

Sincerely,

Nelson

Kennedy’s presidency would be marked by an almost continuous exchange of letters with his chief cold war adversary, Soviet chairman Nikita Khrushchev. It would, in fact, be this unprecedented exchange that would seriously affect the course of history. Not all of the correspondence between the two men would be antagonistic, as evidenced by this letter from Kennedy thanking Khrushchev for having sent Caroline the puppy Pushinka, whose mother had flown in space.

Washington, June 21, 1961

Dear Mr. Chairman:

I want to express to you my very great appreciation for your thoughtfulness in sending to me the model of an American whaler, which we discussed while in Vienna. It now rests in my office here at the White House.

Mrs. Kennedy and I were particularly pleased to receive “Pushinka.” Her flight from the Soviet Union to the United States was not as dramatic as the flight of her mother, nevertheless, it was a long voyage and she stood it well. We both appreciate your remembering these matters in your busy life.

We send to you, your wife and your family our very best wishes.

Sincerely yours,

John F. Kennedy

John and Jacqueline Kennedy’s unprecedented opening of the White House to the world’s most accomplished artists and performers did more than turn the executive mansion into a cultural showcase. It gave some of these artists such as cellist and conductor Pablo Casals the opportunity to express the confidence they had in the young president.

Pablo Casals

Isla Verde K 2 - H 3

Santurce, Puerto Rico

October 16, 1961

The President

The White House

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mr. President:

Your kind invitation to the White House has honored me and given me great pleasure.

Over a year ago I addressed an open letter to the New York Times as I felt that a Democratic victory was essential for the universal reestablishment of faith and trust in the great American nation.

Never before has humanity faced such crucial moments and the desire for universal peace is a prayer of all. Everyone must join in doing their utmost to achieve this goal.

I know that your aim is to work for peace based on justice, understanding and freedom for all mankind. These ideals have always been my ideals and have determined the most important decisions—and the most painful renunciations—of my life.

Your generous foreign aid program and your many welfare plans all prove your practical idealism and have already given hope to those who yearn for liberty.

Therefore I look forward to the opportunity of meeting you personally. May the music that I will play for you and for your friends symbolize my deep feelings for the American people and the faith and confidence we all have in you as leader of the Free World.

Please accept, Mr. President, my respects and my highest esteem.

Sincerely,

Pablo Casals

As evidenced by the following letter to author and poet Carl Sandburg, Kennedy found that sometimes there were unplanned benefits from his being in contact with many of the creative individuals he so admired.

Dear Mr. Sandburg:

You were most kind to send me the article you wrote for the Chicago TIMES in 1941. The President enjoyed it—he particularly liked the phrase “Rest is not a word of free peoples—rest is a monarchial word.”

He may steal it from you some day.

Again many thanks.

Sincerely,

Pierre Salinger

Press Secretary to the

President

In January 1962, Kennedy received a letter from Arthur Schlesinger Sr. in which the historian asked him if, despite his “crushing duties,” he would take the time to join some seventy “students of American history” in filling out a ballot ranking who they thought had been the nation’s greatest presidents. Kennedy’s reply showed the introspection he had gained after a full year in office. It also provided an early indication of one of the projects he might take on after he left the White House.

January 22, 1962

Dear Professor Schlesinger:

Thank you for your letter in regard to our past Presidents.

A year ago I would have responded with confidence to a request to rate their performance in office, but now I am not so sure. After being in the office for a year I feel that a good deal more study is required to make my judgment sufficiently informed. There is a tendency to mark the obvious names. I would like to subject those not so well known to a long scrutiny after I have left this office. Therefore, I hope you will forgive me for not taking part in what I regard as a most interesting and informative poll. …

With kind regards,

Sincerely,

In early June 1962, the American Booksellers Association held its annual convention in the nation’s capital. Kennedy used the occasion to send a telegram to the president of the organization containing both a heartfelt statement and a mock complaint.

JUNE 4, 1962

AS AN AUTHOR, LOYAL TO THE TRADITIONS OF HIS CRAFT, I AM DEEPLY SORRY NOT TO BE ABLE TO JOIN YOU IN PERSON IN ORDER TO DISCUSS THE INADEQUACY OF THE SALES OF A BOOK CALLED “WHY ENGLAND SLEPT”. HOWEVER, MY BROTHER [ROBERT], WHOSE BOOK SOLD EVEN LESS WELL THAN MINE, WILL COME AMONG YOU TONIGHT, AND I ADVISE NO ONE TO APPEAR WITHOUT COPIES OF [HIS] “THE ENEMY WITHIN”. I TRUST THAT THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S APPEARANCE WILL INSPIRE YOU ALL TO SELL MORE BOOKS TO MORE PEOPLE THAN EVER BEFORE IN THE NEXT TWELVE MONTHS. NOW THAT READING IS BECOMING INCREASINGLY RESPECTABLE IN AMERICA, I WANT, BOTH AS AN AUTHOR AND AS A READER, TO EXPRESS MY GRATITUDE TO THE MEN AND WOMEN WHO HAVE LIVED WITH BOOKS, LOVED THEM, SOLD THEM, AND KEPT THEM AN INDISPENSABLE PART OF LIFE.

The mock complaint in Kennedy’s telegram was obviously taken seriously by some who read it, including Pike Johnson Jr., editor in chief of Anchor Books, publisher of the paperback version of Why England Slept.

June 6, 1962

The Honorable John F. Kennedy

The White House

Washington, D. C.

Dear Mr. President:

I read in yesterday’s New York Times your telegram to the American Booksellers Association in which you spoke of “the inadequacy of the sales of a book called “WHY ENGLAND SLEPT”.

Recognizing the spirit in which this telegram was sent, and recognizing also that no author is ever satisfied with the sales of his book, I am, nevertheless, pleased to inform you that the Dolphin edition of “WHY ENGLAND SLEPT”, which has been out approximately two weeks, has already sold 17,000 copies, which is about three times as good as any of our other paperback books have done in many years.

We shall, however, continue to put adequate pressure upon the booksellers of the country to increase this number.

Sincerely,

Pyke Johnson, Jr.

Editor-in-Chief

By Kennedy’s second year in office, he and Eleanor Roosevelt had developed a warm, supportive relationship. So much so that Kennedy had sought to have one of the world’s highest honors bestowed upon her.

February 1, 1962

Dear Mr. President:

I have learned through Mr. Lee White and Mr. Abba Schwartz that you have sent a letter nominating me for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962. I am overcome by such an idea and I must frankly tell you that I cannot see the faintest reason why I should be considered. Of course, I am grateful for your kindness but I shall not be surprised in the least if nothing comes of it but my gratitude to you for having thought of this gesture will be just as great.

With my warm good wishes,

Very cordially yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

One letter Kennedy received was quintessentially Harry Truman.

Harry S. Truman

In dependence, Missouri

June 28, 1962

Dear Mr. President:

It looks as if the Republerats haven’t changed a bit since 1936. President Roosevelt had his troubles with them—so did I.

Mr. President, in my opinion you are on the right track. Don’t let ’em tell you what to do. You tell them, as you have! Your suggestions for the public welfare, in my opinion, are correct.

This is a personal and confidential statement for what it may be worth. You know my program with these counterfeits was “Give ’em Hell” and if they don’t like it, give them more of the same. I admire your spunk as we say in Wisconsin.

Sincerely

Harry S. Truman

This is a pretentious note but I had to write it.

Do as you please with it. Perhaps it ought to go into the “round file.”

By the middle of Kennedy’s second year in office, Kennedy and Truman had engaged in regular correspondence. And Kennedy, knowing that he would get a well-considered reply, had seriously begun asking the former president for advice on a number of important matters, including his Trade Program.

A typically plainspoken letter from former president Harry Truman to Kennedy

Dear Mr. President:

I am anxious that you have directly from me a copy of the special message which I am sending to Congress on the Trade Program.

The wonderful reaction to your address at the dinner Saturday evening has been most gratifying. It certainly pleased me to have you speak out as you did. I know that as we enter the debate phase no help will be more important than yours.

With warmest regards,

Sincerely,

John F. Kennedy

February 6, 1962

Dear Mr. President:

I certainly did appreciate your letter of January 25th, enclosing a copy of your “Message on Trade” to the Congress on January 24th.

Your letter came while I was back East and I have just now had an opportunity to read it carefully. It is a great message and I think hits the nail on the head right where it ought to be hit.

I sincerely hope for the successful passage of the legislation, which you requested, as it ought to solve a great many of our problems.

Again, I want to tell you that I appreciate your thoughtfulness, in sending me a copy of the message with your own personal letter attached, more than I can tell you.

Sincerely yours,

Harry S. Truman

Among the hundreds of letters Kennedy received from college students was a specific request from a Yale undergraduate. Neither the sender nor the president could have predicted that this particular student would, some forty-five years later, come within thirty-five electoral votes of gaining the presidency himself, or that he would eventually serve as the nation’s secretary of state.

1078 Yale Station

September 24, 1962

To whom it may concern:

Dear Sir:

I am at the moment involved in the preparation for a debate on the resolved; “That the Kennedy administration’s Domestic Program has failed to meet the challenge(s) of the future.”

I would greatly appreciate an administration statement on this issue as soon as possible—if available. I already intend to speak against the resolved but I would naturally be interested in a first hand idea of what the administration feels on this issue and how it would approach its naturally negative answer.

In all hopes that I am not taking your time nor trying your patience.

Sincerely,

John Forbes Kerry

As both a student of history and a statesman, Kennedy was an ardent admirer of Winston Churchill. So much so that early in his presidency he began to advocate for the bestowal of American citizenship on the legendary British leader whose alliance with the United States had been forged in World War II. On August 14, 1961, the twentieth anniversary of the signing of the historic Atlantic Charter, Kennedy sent Churchill a telegram commenting on both the importance and the enduring legacy of the Charter.

AUGUST 14, 1961

TODAY MARKS THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE ATLANTIC CHARTER. TIME HAS NOT CHANGED AND EVENTS HAVE NOT DIMMED THE HISTORIC PRINCIPLES YOU THERE EXPRESSED WITH PRESIDENT FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT. OUR TWO NATIONS ARE STILL UNITED ON THE COMMON GOALS YOU TWO SO ELOQUENTLY CHARTED AT SEA. WE STILL BELIEVE THAT ALL NATIONS MUST COME TO THE ABANDONMENT OF THE USE OF FORCE. WE STILL SEEK A PEACE IN WHICH ALL THE MEN IN ALL THE LANDS MAY LIVE OUT THEIR LIVES IN FREEDOM FROM FEAR AND WANT. AND WE ARE STILL DETERMINED TO PROTECT THE RIGHT OF ALL PEOPLES TO CHOOSE THE FORM OF GOVERNMENT UNDER WHICH THEY WILL LIVE—AND TO OPPOSE ALL TERRITORIAL CHANGES THAT DO NOT ACCORD WITH THE FREELY EXPRESSED WISHES OF THE PEOPLE CONCERNED.

YOUR OWN NAME WILL ENDURE AS LONG AS FREE MEN SURVIVE TO RECALL THESE WORDS.

(S) JOHN F. KENNEDY

THE RIGHT HONORABLE

SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL

LONDON, ENGLAND

A day after receiving Kennedy’s telegram, Churchill replied, reaffirming the Atlantic Charter’s principles and reminding Kennedy of the vital role he now played in world affairs.

1961 AUG 15 PM 1 05

VWN2 88 VIA RCA

WESTERHAM ENGLAND 1512 AUGUST 15 1961

THE PRESIDENT

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON

MR PRESIDENT I AM INDEED GRATEFUL TO YOU FOR YOUR MESSAGE STOP THE TERMS OF THE ATLANTIC CHARTER OF TWENTY YEARS AGO EMPHASIZED THE PRINCIPLES WHICH THEN AND NOW GUIDE THE POLICIES OF OUR GREAT DEMOCRACIES STOP LET US NEVER DEPART FROM THEM NOR DESIST FROM OUR EARNEST ENDEAVOUR TO ESTABLISH THEM THROUGOUT THE WORLD STOP I SEND YOU MY HEARTFELT GOOD WISHES FOR THE MOMENTOUS AND PREEMINENT PART YOU PLAY IN THE SHAPING OF OUR DESTINIES

WINSTON S CHURCHILL

One of the strongest supporters of Kennedy’s desire to bestow American citizenship on Winston Churchill was a remarkable woman named Kay Murphy Halle. A glamorous Cleveland department store heiress, Halle became best known for the ways in which she formed close personal friendships with many of the leading figures of her day, including Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. On August 19, 1961, Halle wrote to Kennedy stressing the urgency of granting citizenship to Churchill, a letter also notable for its unique glimpse into the aging Churchill, his thoughts, and his surroundings.

August 19, 1961

President John F. Kennedy

The White House

Washington, D. C.

Dear President Kennedy:

I thought it would please you to know that Randolph and I spent the day with Sir Winston and his family at Chartwell. We found him seated on the terrace overlooking his water gardens girdled by the crenelated rawliver-red brick walls he had built with his own hands which make Chartwell seem not unlike a castle close. A light-beige-colored South African campaign hat shaded his eyes as he watched the gambols of a gray pony that had escaped from a nearby gypsy camp and leapt the walls into a Chartwell pasture where his Belted Galloway cattle were grazing. Not a combination of its gypsy owners, a Scotland Yard detective, a London Bobby and Vincent, the head gardener was able to corral the freedom-loving pony. Sir Winston could not help cheering the pony’s determination to avoid capture.

When lunch was announced, we were lifted to the dining room in an elevator—a present from his friend, Lord Beaverbrook—and my host bade me sit next to him at the table. Several times he turned to speak to me of “That splendid leader, your President.” When the fish course arrived, he waved away any assistance from his red-haired nurse as he rose from the anesthesia of his great age and lifted his glass of hock. Then, turning to me, he proposed a toast, “To your great President Kennedy and … and … ours.” I told him I had seen you on the eve of my departure and that you had sent him warmest greetings. He smiled a jack-o’-lantern grin and I could see he was pleased. He asked me, “Is there a picture of me now at the White House?” Lady Churchill’s eyes signaled “No.” He muttered that perhaps I could take one to you.

I had brought with me a clipping from the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune of the full exchange of messages between Churchill you and President Kennedy Sir Winston on the twentieth anniversary of the signing of the Atlantic Charter. He read it through, then promptly invited me to his bed-study to see the original draft copy of the August 14, 1941 Joint Declaration of the Atlantic Charter, with some suggested changes for Point III written in his own hand to President Roosevelt. Thereupon he presented me with a copy, taking particular care to point out the significance of Point III—”That’s mine!”—which was to become Point III of the United Nations Charter: “They respect the right of all people to choose the form of government under which they will live.”

It was only one of many of the historic mementoes that ringed his room. Most dramatic were the three flags hanging from oaken beams in the high ceiling of his study. One of these was the Cinque Ports, a medieval league of coastal cities of which Churchill was warden which Churchill enjoyed hanging from his manor house in Chartwell and on his car by special decree of the Queen. The other two were the Flag of the Knight of the Garter and—most dramatic of all—a tattered Union Jack sent him by General Montgomery, the first flag to fly over Rome after the Allied entry.

On awakening each morning, his eyes would first rest on a wall opposite his bed on which were hung an engraving of Lord Nelson, a new painting of Bernard Baruch, and a fine drawing of John, Duke of Marlborough. I was amused to note a Bible lying on the shelf of his bedside table.

On top of The Holy Book, he had placed an autographed photograph of Stalin face downwards, perhaps in the hope that the Communist leader might absorb its contents!

Discussions concerning The Daily Express’ “monstrous position on Berlin” and the eddies of British politics all swirled around his head. It mattered not to him. All he seems to brood upon is Anglo-American amity. I leaned close to him all through lunch to catch his fragmentary words. Some reminded me so much of his sentences in a speech he gave July July 4, 1950 in London. “The British and the Americans do not war with races and governments as such. Tyranny external or internal is our foe whatever trappings or disguise it wears, whatever language it speaks or perverts.” “Undying fraternal association” was much on his lips.

The best way to describe the appearance of the Great Man at this moment, with his beautifully ordered house, loving staff and family around him, is in the words he used in his profile on the aging Admiral Lord “Jackie” Fisher. ‘As in a great castle which has long contended with time, the mighty central mass of the donjon towered up intact and seemingly everlasting. But the outworks and the battlements had fallen away, and its imperious ruler dwelt only in the special apartments and corridors with which he had a life long familiarity.’

I fear, Mr. President, that if the Honorary American Citizenship we discussed is not bestowed on Sir Winston soon, even his ‘mighty central mass’ will have crumbled. Though his cheek was warm when I kissed him farewell, both hands were cold. I left him, glasses on the end of his nose, reading Thomas Hardy’s TESS OF THE D’URBERVILLES.

Faithfully

Kay Murphy Halle

Granting U.S. citizenship to even as giant a figure as Winston Churchill required the approval of the United States Congress, a process that, for Kennedy, would take an agonizingly long two years. In the meantime, the Kennedy/Churchill correspondence would continue, as evidenced by this exchange of telegrams occasioned by a serious illness Churchill had suffered.

JULY 6, 1962

THE HONORABLE WINSTON CHURCHILL

DEAR SIR WINSTON, WE HAVE BEEN ENCOURAGED BY THE REPORTS OF THE PROGRESS YOU HAVE MADE AND HEARTENED AGAIN BY YOUR DISPLY [DISPLAY] OF INDOMITABLE COURAGE IN THE FACE OF ADVERSITY. THE WISHES OF ALL OUR PEOPLE, AS WELL AS THOSE OF MRS. KENNEDY AND I, GO TO YOU.

PRESIDENT JOHN. F. KENNEDY

WA360 40 PD

ZL LONDON (via WU cables) JULY 7, 1962 551P EDT

THE PRESIDENT

THE WHITE HOUSE

I AM MOST GRATEFUL TO YOU MR. PRESIDENT AND TO MRS. KENNEDY FOR YOUR MESSAGE AND SYMPATHY WHICH I RECEIVED WITH THE GREATEST PLEASURE ALL GOOD WISHES.

WINSTON CHURCHILL.

Finally, in the beginning of April 1963, it became clear that the U.S. Congress was about to enact Public Law 88-6 declaring “that the President of the United States is hereby authorized and directed to declare that Sir Winston Churchill shall be an honorary citizen of the United States of America.” Informed of the impending act, the ever-eloquent Churchill wrote to Kennedy.

28, Hyde Park Gate

London, S.W.7

6 April, 1963

Mr. President,

I have been informed by Mr. David Bruce that it is your intention to sign a Bill conferring upon me Honorary Citizenship of the United States.

I have received many kindnesses from the United States of America, but the honour which you now accord me is without parallel. I accept it with deep gratitude and affection.

I am also most sensible of the warm-hearted action of the individual states who accorded me the great compliment of their own honorary citizenships as a prelude to this Act of Congress.

It is a remarkable comment on our affairs that the former Prime Minster of a great sovereign state should thus be received as an honorary citizen of another. I say “great sovereign state” with design and emphasis, for I reject the view that Britain and the Commonwealth should now be relegated to a tame and minor role in the world. Our past is the key to our future, which I firmly trust and believe will be no less fertile and glorious. Let no man underrate our energies, our potentialities and our abiding power for good.

I am, as you know, half American by blood, and the story of my association with that mighty and benevolent nation goes back nearly ninety years to the day of my Father’s marriage. In this century of storm and tragedy I contemplate with high satisfaction the constant factor of the interwoven and upward progress of our peoples. Our comradeship and our brotherhood in war were unexampled. We stood together, and because of that fact the free world now stands.

Nor has our partnership any exclusive nature: the Atlantic community is a dream that can well be fulfilled to the detriment of none and to the enduring benefit and honour of the great democracies.

Mr. President, your action illuminates the theme of unity of the English-speaking peoples, to which I have devoted a large part of my life. I would ask you to accept yourself, and to convey to both Houses of Congress, and through them to the American people, my solemn and heartfelt thanks for this unique distinction, which will always be proudly remembered by my descendants.

Winston S. Churchill

On April 9, 1963, Public Law 88-6 was officially enacted and was signed by Kennedy in a ceremony attended by dignitaries from both the United States and Great Britain. Four days later, Sir Winston wrote once again to the president.

Private

My dear Mr. President,

When Mr. David Bruce called on me to bring me the Act of Congress by which I was made a Citizen of the United States, he also handed me your gift of the signatures of those present at the ceremony and the pen with which you signed the Act of Congress.

I have already expressed to you, Mr. President, and to the people of America the strong sentiments that your action aroused in me. I would now like to add my very warm thanks to you personally, both for the part you played in bestowing this signal honour on me, and for these most agreeable gifts with which you accompanied it. They will be cherished in my archives for my family, and they will be a constant reminder to me of your goodwill and that of the American people.

With all good wishes,

I remain, Yours very

sincerely,

Winston S. Churchill

As chief executives before Kennedy had learned, even the presidency did not offer protection from the solicitations of entrepreneurial citizens eager to hawk their wares.

W.N. HYDER

Real Estate and Insurance

Insurance in Cash

43 Devereux Building

Utica, New York

October 9, 1962

President John F. Kennedy

White House

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mr. President:

We have just been retained to sell an estate on Dark Island in the St. Lawrence River, usually referred to as “Stone Castle”, owned by the LaSalle Military Academy.

The property consists of a Main Building of 28 rooms, with 9 master bedrooms each with bath, is of stone construction, on 7 acres of land, on an island, that is not accessible except by boat or plane.

It is in the main channel of the St. Lawrence River, high above the water, a Scottish Castle with beautiful trees in abundance, nice lawns, has its own electric plant, with two Boat Houses, and a Squash Court Building 25’ × 54’.

Although this could be used for a Hotel, Show Place, or Tourist attraction, or International Yacht Club, the writer remembers visiting the Secretary of State Dulles on Duck Island, not too far away, where the Republican leaders talked over strategy and other matters of national interest.

MY THINKING, KNOWING A LITTLE OF WHAT YOU WILL BE FACING SOON, TELLS ME THAT THIS IS JUST THE PLACE FOR A PRESIDENTIAL HIDEAWAY, where you can have peace of mind, secretly consult with whoever requires attention from you, (without) interference or observance.

Replacement Cost |

$1,000,000.00 |

Sale Price |

225,000.00 |

Sincerely Yours

W.N. Hyder, Broker

The Kennedy wit and sense of humor which became trademarks of his presidency were evident in the following exchange of letters between him and his friend Leonard Lyons, the popular New York Post columnist. In late August 1961, Lyons passed by the window of an autograph shop that contained a display of presidential autographs along with the price each signature was fetching. In his initial letter to Kennedy, Lyons issued a lighthearted warning.

Leonard Lyons

October 2, 1961

Dear Mr. President:

In the event you might be anxious about how you rate in history, I think you should know about this market: a manuscript and autograph framing shop on 53rd Street and Madison Avenue has a window display of framed presidential autographs. In each is either a tinted photo or a medallion of a President.

George Washington’s sells for $175, U.S. Grant’s sells for $55, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s for $75, Teddy Roosevelt’s for $67.50, John F. Kennedy’s for $75.

Please don’t bother to acknowledge this, for two reasons:

(1) You’re too busy; and

(2) If you sign your name too often, that would depress the autograph market on E. 53rd Street.

Sylvia joins me, of course, in sending you fondest regards.

Sincerely,

Leonard

A tongue-in-cheek Kennedy responded by demonstrating that he was heeding Lyon’s warning.

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

October 11, 1961

Dear Leonard:

I appreciate your letter about the market on Kennedy signatures. It is hard to believe that the going price is so high now. In order not to depress the market any further I will not sign this letter.

Best regards,

Delighted by Kennedy’s response, Lyons wrote back, asking the president’s permission to share it with his readers.

New York Post