THE MOUSE and his child stood in the darkness and heard the wind whistling over the ice and snow. Under the wind the winter silence waited, and the ice creaked with the cold. Hours passed, and the sky was growing light when the child, who stood facing the bank, said, “Someone’s coming.”

“Is it Muskrat?” asked the father.

“I don’t know,” said the child. “He doesn’t look anything like Manny Rat. He’s larger and stouter. He has a different kind of tail. And he has a nice face and he limps.”

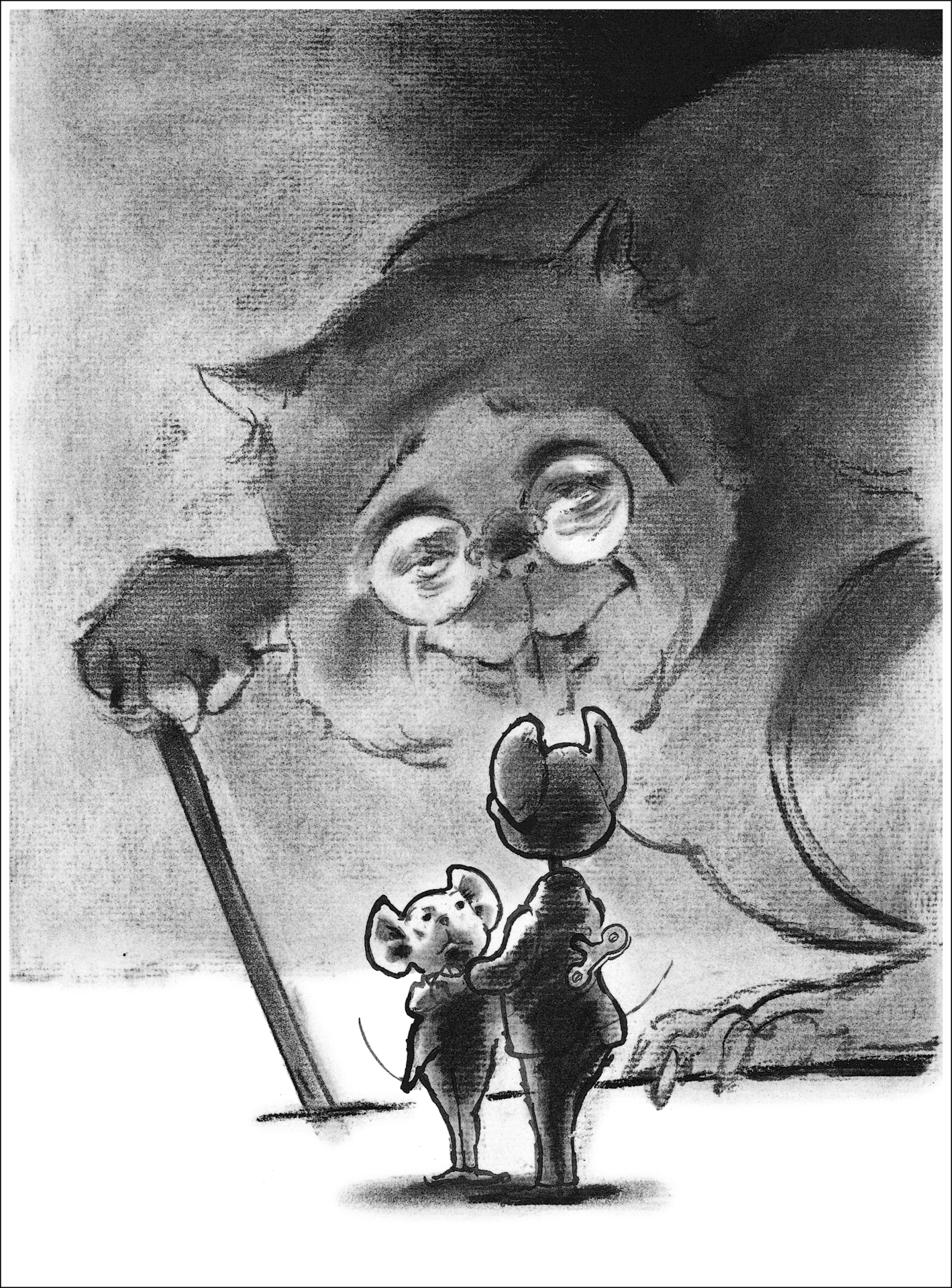

The muskrat, who looked somewhat like a large brown meadow mouse, approached them slowly. He had lost one leg in a trap, and as he walked he bobbed with a step, step, hop — step, step, hop. His whole manner suggested one continuous train of solid, round, furry thought, and he was mumbling softly to himself.

Muskrat looked up as he bumped into the mouse and his child. “You’re a little early,” he said, “but that’s all right. We can start right here. The lesson for today is the Them Tables. Begin.” He settled back on his haunches and waited.

“I don’t know what you mean,” said the mouse father.

“Very well,” said Muskrat, “I’ll help you. Them times Us equals?”

“I don’t know,” said the father. “Really, I —”

“Equals Bad,” said Muskrat, whacking the ice with the flat of his tail. “You were supposed to have learned that.”

“I’m sorry,” said the mouse father.

“Don’t be sorry,” said Muskrat. “Come next time with your lesson prepared. Continue, please. Them plus Trap times Us equals?”

“Worse?” said the mouse child.

“Good boy!” said Muskrat. He came closer and peered nearsightedly at father and son. “I beg your pardon,” he said. “I took you for two of my regular pupils. You’re new here, then?” He wrinkled his nose. “You smell a little Themmy. Been in a trap, have you? You must tell me about it. Come over to my place and visit for a while.”

“You’ll have to wind me up,” said the father. “There’s a key in the middle of my back.”

Muskrat looked at the key. “Of course,” he said as he wound it, “I remember now: Key times Winding equals Go. She had just such a key in her back.”

“Who?” said the father.

“The tin seal,” said Muskrat.

“The seal!” said the child. “Did she have a platform on her nose?”

“No,” said Muskrat. “There was only a metal rod that turned, and that was how she used to wind up string for me. Many a cozy evening we spent that way. Charming young lady!” He smiled, lapsing into a silent reverie.

“Where had she come from?” asked the child.

“Who?” said Muskrat.

“The seal.”

“Ah, the seal! She had been traveling with a rabbit flea circus, but the whole concern broke up not far from here. A fox ate the rabbit, the fleas joined the fox, and the seal came to stay with me.”

“Where is she now?” asked the father as they walked toward the other side of the pond.

“I don’t know,” said Muskrat. “She found the life here dull after a time, and went off with a kingfisher. Was she a friend of yours?”

“We were close,” said the father, “long ago.”

“Well, that’s how it is,” said Muskrat. He shook his head thoughtfully as he went with his step, step, hop — step, step, hop. “Why into Here often equals There, and so one moves about.”

“You have a strange way of speaking,” said the mouse father.

“I’m always looking for the Hows and the Whys and the Whats,” said Muskrat. “That is why I speak as I do. You’ve heard of Muskrat’s Much-in-Little, of course?”

“No,” said the child. “What is it?”

Muskrat stopped, cleared his throat, ruffled his fur, drew himself up, and said in ringing tones, “Why times How equals What.” He paused to let the words take effect. “That’s Muskrat’s Much-in-Little,” he said. He ruffled his fur again and slapped the ice with his tail. “Why times How equals What,” he repeated. “Strikes you all of a heap the first time you hear it, doesn’t it? Pretty well covers everything! I’m a little surprised that you haven’t heard of it before, I must say. It caused a good deal of comment both over and under the pond, and almost everyone agreed that the ripples from it were ever-widening.”

“Your work is, of course, known everywhere,” said the mouse father, “and although we were not acquainted with Muskrat’s Much-in-Little we have heard a great deal about you.”

“Ah!” said Muskrat. He smiled a little smile and groomed his fur complacently. “Yes,” he said. “I have some small reputation, perhaps. I am not entirely unknown. Not that I care about such things.” He wound up the father again, and they continued across the ice.

“We have traveled far to see you,” said the father, “in the hope of learning how to be —”

“Like me,” said Muskrat. “I thank you humbly for the compliment, and I have the most profound respect for your admiration. Yes. There is a small but growing circle of students and followers whom I hope to guide along the path to —”

“Self-winding,” said the father.

“I beg your pardon,” said Muskrat. “What did you say?”

“Self-winding,” said the child. “We want to be self-winding, so we can wind ourselves up. Euterpe the parrot said that you’ve fixed broken windups. Can’t you fix us?”

“I’m afraid that’s a little out of my line,” said Muskrat. “Oh, I’ve tinkered with clockwork now and then, but I have long since gone beyond the limits of mere mechanical invention. That’s applied thought, you see, and my real work is in the realm of pure thought. There is nothing quite like the purity of pure thought. It’s the cleanest work there is, you might say.” He nodded and mumbled softly to himself as he bobbed along with his uneven limping gait.

The sun was up when they reached the beaver lodge and the snowy dome gleamed rosy in the morning light. Muskrat sniffed as he looked up at the structure that towered above them, its snow-covered smoothness broken by projecting brush and twigs and the cut ends of saplings. “They came here a few seasons back,” he said, “when there was nothing here but a little trickle through the grass. They built the dam, made the pond, put up this lodge, and they pretty well run the whole place now.”

There was a murmur of voices inside the lodge, and Muskrat leaned close to listen. “Always the same thing,” he said. “How many aspens they’ve cut down. How many birches. How they’re going to improve the dam next year. Dull fellows! Yet I suppose they have their place. It is, after all, their pond that supports my pure thought. And in spite of the hurly-burly of industry and the working-class atmosphere, my roots are here. Not only my roots, but my stalks and leaves — arrowhead and smartweed, cattails and wild rice. Yes,” he said, “this is my home, where my work has brought me pondwide respect and esteem. Let the beavers have their wealth! I am content with the treasures of the mind.” He smiled with satisfaction, and limped along beside the mouse and his child with a step, step, hop — step, step, hop.

“Here’s my place,” said Muskrat, as they came to the smaller of the two domes on the ice. “But we can’t get into it here; the entrance is underwater, from a tunnel on the far bank.” From inside the lodge came the sound of two young muskrats laughing. “Merry little rascals!” said Muskrat. “That must be Jeb and Zeb, come for their lesson.”

“Hee!” said one of the voices inside the lodge. “Hee times Hoo equals Hechoo!”

“Rinkum times Dinkum equals Rinkumdinkumdoo!” said the other.

“What are they talking about?” asked the mouse child.

“They’re making fun of my Much-in-Little,” said Muskrat, managing a smile. “High-spirited lads!”

“Jeb,” said the voice of Zeb, “what do you want to be when you grow up?”

“A beaver,” replied Jeb without hesitation.

“A beaver?” said Zeb.

“A beaver!” echoed Muskrat.

“Right!” said Jeb, clicking his teeth and whacking the floor of the lodge as hard as he could with the flat of his tail. “Beavers do things! They cut down trees! CHONK! BONK! Make dams! SPLASH! KERPLONK! Beavers get rich!”

“Maybe old Muskrat knows all that stuff too,” said Zeb. “Maybe he could cut down trees if he wanted to.”

“Who, him?” snorted Jeb. “He can’t do anything! My daddy says old Muskrat got caught in a trap once and it shook his brains up. All he’s good for now is teaching kids the Them Tables.”

“Ahem!” said Muskrat. He climbed onto the lodge and jumped up and down several times, stamping heavily on the roof. There was instant silence inside. “Boys!” he called.

“Yes, sir!” came the polite response.

“No lesson today,” said Muskrat. “Very busy. Great many things to do. Come back next week. Bye-bye.”

There was a single splash inside the lodge as Jeb and Zeb dove into the water and swam home under the ice.

“You were saying —” began the father, hoping to bring the muskrat back to the subject of self-winding.

Muskrat turned away from him. “Crushed!” he said in a choked voice. “I am utterly and completely crushed! Good for nothing but to teach children the Them Tables! That’s what the whole pond thinks of me!” he whispered brokenly. “That’s the sort of respect they’ve had for me!”

“You mustn’t be so upset,” said the father. “Your work is admired everywhere. That is why we came to you for —”

“Beavers!” hissed Muskrat, doing a little limping dance of irritation. Then he began to pace back and forth slowly: step, step, hop — step, step, hop. “CHONK! BONK!” he said. “Beavers do things, eh? Very well, then, I’ll do something!”

“What will you do?” asked the mouse child.

“I don’t know,” said Muskrat, “but it’ll be something that’ll make them sit up and take notice!” His pacing quickened to a step-step hoppity — step-step hoppity. Then he stopped.

“I can’t pace right anymore,” he said. “My best Much-in-Little thinking was done before I lost my leg in the trap; I can’t reason as I did when I was whole. There’s a universal rhythm that the mind must catch. I used to feel it; now I don’t. My mental powers are hobbled, like my gait.”

“Perhaps,” said the mouse father, lurching ahead on his bent legs, “if we pace for you until you solve your problem, you might help us with ours?”

“What’s that?” asked Muskrat.

“What’s what?” said the father.

“The problem you want help with,” said Muskrat.

“SELF-WINDING!” said the father.

“No need to shout,” said Muskrat. “Yes, that seems fair enough, and your pacing, while lacking something in style, is nonetheless steady. Let’s go to my workroom and get started.”

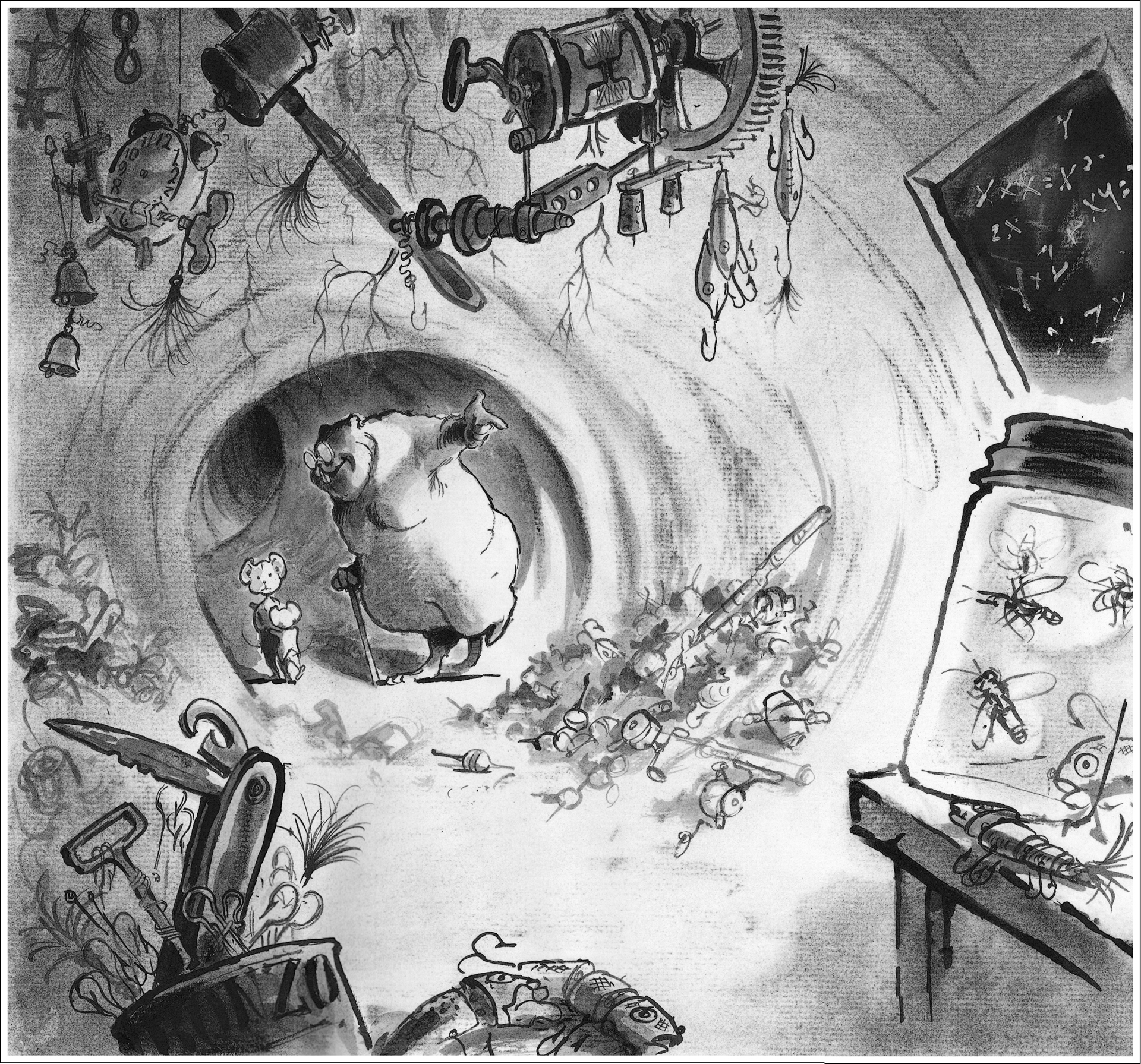

They had reached the shore of the pond, and Muskrat took the mouse and his child down into the tunnel that led to his underground den. Crystals of frost winked from the frozen walls, and the dark, cold, chthonic smell of earth pervaded the slanting passage. A faint, greenish glow appeared ahead at the doorway of the den.

“This is where I do most of my thinking,” said Muskrat. “The lodge in the pond is rather too much in the middle of things.” He followed the mouse and his child into the room. A little group of firefly students had lit up when the muskrat’s familiar step was heard in the tunnel, and now they said in unison, “Good morning, sir.” Devoted followers who had outstayed the summer, they lived in a glass jar in a corner, and their dormitory cast its pale and blinking glow on the clutter all around them. An oilcan and a ball of string lay among mussel shells and the forgotten nibbled ends of roots and stalks beside a small terrestrial pencil-sharpener globe; a BONZO DOG FOOD can stood filled with salvage from the bottom of the pond: rusty beer-can openers, hairpins, fishhooks, corroded cotter pins, tangles of wire, drowned flashlight batteries, a jackknife with a broken blade, and part of a folding ruler. Near it sprawled improvisations of discolored pipe cleaners, tobacco tins, old fishing-license badges, draggled wet- and dry-fly feathers, coils of catgut, jointed lures that bristled with hooks and staring eyes — all the neglected apparatus of past experiments in applied thought. Against the wall leaned a bit of broken slate with X’s, Y’s, and Z’s scrawled on it. The air was still and warm, the odor studious and strong.

Muskrat rubbed his paws together, hummed a little tune, heaved everything anyhow into the center of the den, and smoothed a circular track around the floor. “Now, then,” he said, and winding up the father, he started the mouse and his child on their rounds.

The curved walls of the den kept them in the track. The child’s good-luck coin gleamed in the pale light of the fireflies as it clinked against the drum; the glass-bead eyes of father and son caught the glow as — now seen, now lost behind the jumble — they circled steadily around the muskrat while he pondered.

“We’re going in a circle again, Papa,” said the child, “but this time it’s going to get us somewhere.”

“Yes,” said the father, “things seem to be looking up. And Manny Rat will certainly have lost our trail by now; I’m beginning to think Frog may have been wrong about the enemy waiting for us at the end.”

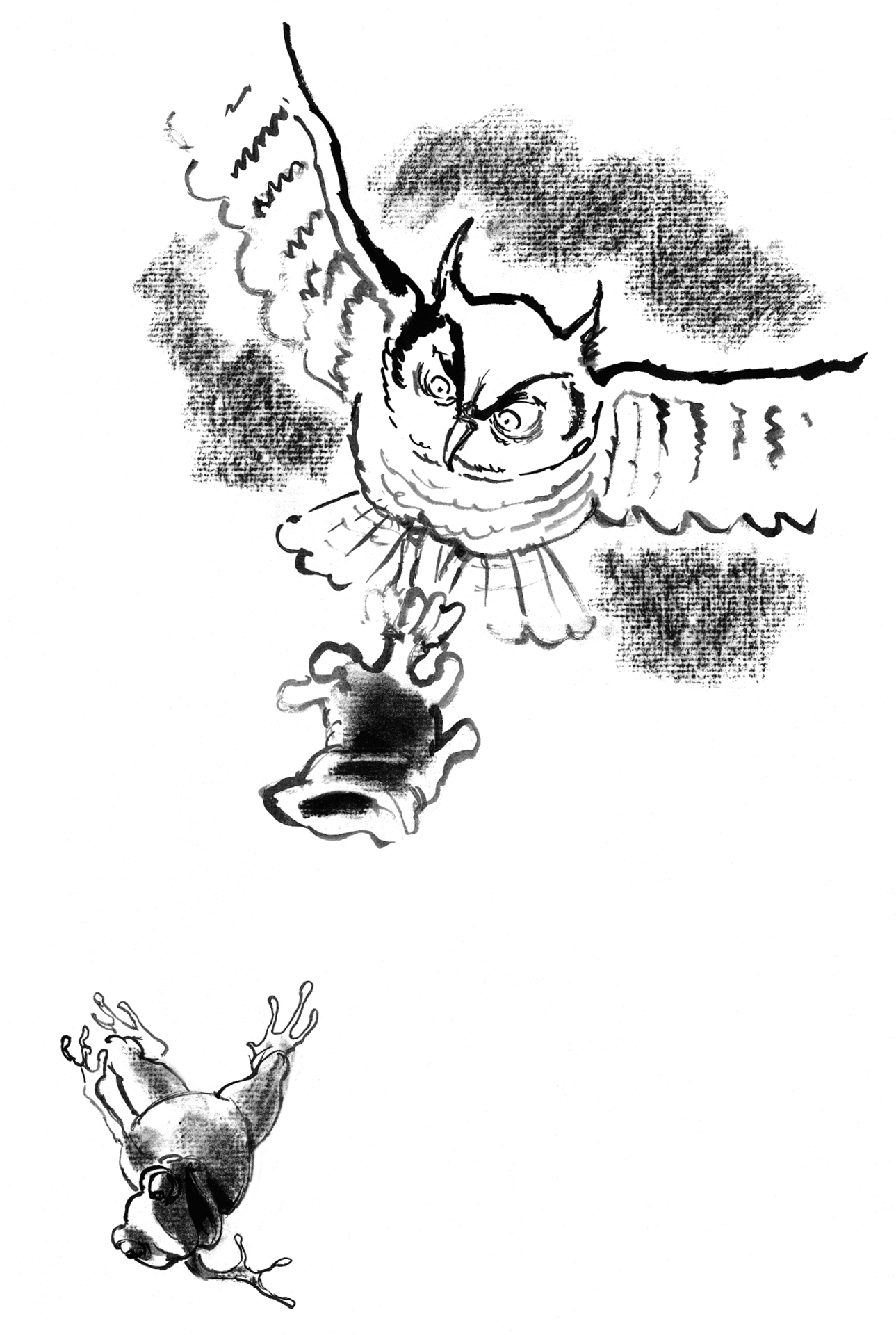

“And maybe Uncle Frog wasn’t killed by the horned owl,” said the child. “Maybe he’ll find us again. He’s very wise.”

“Wise or not, I don’t think anyone returns from the horned owl’s talons,” said the father sadly.

“I beg your pardon,” said Muskrat, “but I must ask you to be quiet. Absolute silence is essential to Much-in-Little thinking.” The mouse and his child said no more, but paced in silence.

“First,” said Muskrat, “we must define the problem; that’s how you begin.”

“Hear him!” said the senior fireflies, and the junior ones made mental notes. Muskrat sat on his haunches, rocking slightly, his whiskers quivering with the intensity of his thought, which he interrupted only when it was necessary to wind up the mouse father.

“The problem,” he said, “is to do something, something big, something resultful — something, in short, that will make both a crash and a splash and show the whole pond how truly much is meant by Muskrat’s Much-in-Little.”

“Why times How equals What!” blurted one of the smaller fireflies, on the chance that an oral examination was taking place.

“Quiet!” said his elders, and quenched his light.

“Now,” continued Muskrat, “what’s big and crashful and splashful? CHONK! BONK! The felling of a tree. Suppose we say, then, that the problem is to fell a tree.” His usually mild eye flashed with something more than the fireflies’ feeble light. “A big tree,” he said.

“To fell a tree,” repeated the mouse father as he paced.

“Hush!” said Muskrat. “Now, who fells trees? Beavers. How do beavers fell trees?” He clicked his teeth.

“Teeth!” said the mouse child.

“Do be quiet,” said Muskrat. “Teeth is right. The teeth of beavers are of the proper size, shape, and sharpness for cutting down trees. Mine are not, but theirs are. When a beaver gnaws at a tree for a period of time, that tree will fall.” He picked up a withered brown arrowhead stalk and chewed it reflectively. “So we may now reduce this data to the following Much-in-Little — ”

“Pay attention!” said the senior fireflies, glowing brighter.

“Beaver plus Teeth times Gnaw times Time times Tree equals Treefall,” said Muskrat.

“Bravo!” the mouse father cried out involuntarily.

“Thank you,” said Muskrat. “That’s first-rate pacing, by the way.” He drew himself up and launched himself anew upon his thoughts. “Let us now disassociate the tooth from the beaver,” he said.

“How his mind soars!” exclaimed the fireflies all together, and intensified their light, so that the glass eyes of the fish lures blazed up in the gloom, staring in wild surmise.

“You’ve got to be able to make those daring leaps or you’re nowhere,” said Muskrat. “Where was I?”

“Disassociate the tooth from the beaver,” said the mouse father.

“Yes,” said Muskrat, “and consider it simply as any tooth of the proper kind, or as we might say, ToothK.”

“ToothK,” said the mouse child.

“ToothK times Gnaw,” said the father.

“ToothK times Gnaw times Time times Tree equals Treefall,” said Muskrat. “Wait — it’s coming to me now!” The fireflies had dimmed a little; now they kindled up again. “I’ve got it!” shouted Muskrat.

“What?” said the mouse and his child together.

“X!” said Muskrat, “X!”

The fireflies abandoned all reserve, and flashed with such a light that Muskrat’s shadow loomed up huge and black upon the wall behind him.

“He’s done it!” said the father to the child. “He’s made the leap.”

“X!” said Muskrat, dancing about with a steppity hop, and bumping into things with every step. “It needn’t be a tooth at all! Anything of the proper k, which is to say size, shape, and sharpness, will do it.” He limped to the broken piece of slate, hastily rubbed it clean with his paw, wrote XT = TF, and sat back, rocking on his haunches. “X times Tree equals Treefall,” he said huskily, and crooned beneath his breath a little song of triumph.

“Ah!” said the fireflies. They blazed up once more all together, then sank back, exhausted, to a pale glimmer. The room grew dim and dark.

“Tremendous!” said the mouse father. “Simply tremendous.”

“Well, we’ve solved the problem,” said Muskrat, “and I tell you frankly I couldn’t have done it without you. Steady pacing is what does the trick.”

“Thank you,” said the mouse father. “Now we can go on to the problem of self-winding.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Muskrat, “ — as soon as we’ve felled the tree. There’s very little to it, I’m sure, once you’ve got the X, and I’m off to find one now.”

“What will the X be?” asked the mouse child.

“I don’t know,” said Muskrat, “but I’ll know it when I see it.” And he was out of the den, into the tunnel, and gone, with a step, step, hop — step, step, hop.

* * *

THE MUSKRAT was away for several days. The fireflies, out of courtesy, kept going at half strength the whole time, while the mouse and his child, unwound, stared at the Much-in-Little on the dim slate and smelled the darkness of the earth.

When they heard the muskrat’s footsteps in the tunnel on the day of his return, the sound was new and different: scuff, scuff, slide, hop — scuff, scuff, slide, hop. At length Muskrat came into the den and flung down an ax, the handle of which had been broken off short.

“Here it is,” he said: “X. I found it at a Them place, and I must say I don’t care for the smell of it, besides which it’s a great deal bigger than I’d like it to be.” He limped around the ax, looking down at it uneasily. “Well, why not?” he said. “Once you accept X, the size doesn’t really matter. Now, then — to work! Our objective is … ah … our goal is … um …”

“To fell a tree,” said the mouse father.

“Exactly,” said Muskrat. “You have a head for detail; I admire that. Now to begin! For applied thought you need string,” he said. After finding his ball of string where it lay in the clutter, he took the ax and the mouse and his child out through the tunnel and up to the stand of birch and aspen trees beside the pond, where the beavers had been working earlier that year. Gnawed and pointed stumps stood everywhere, casting their lopped-off shadows on the snow among the full-length shadows of the bare trees all around them. Muskrat’s breath made little clouds in the clear, cold air as he limped about, blinking in the sunlight while he considered where his project should be sited. High above them flew the blue jay on his journalistic rounds, pausing to sail for a moment on motionless wings so sharply dark against the blue sky that an edge of white showed all around them. The mouse and his child stood dark and still on the white snow. The keen wind whistled through their tin and hummed in the father’s unwound spring. The muskrat stood solidly planted on the earth, thinking hard as he looked with admiration at the tooth marks on the stumps.

“Those beavers may not have intellect,” he said, “but they’ve got method.” He began to fuss with sticks and stones, muttering to himself.

“Will it take long?” asked the mouse father.

“Not very long, as these things go,” said Muskrat. Having found a short, thick branch that had fallen during a storm, he was seated astride it, laboriously planing it flat with the heavy ax head.

“Now,” he said, panting from his efforts and puffing out little clouds of misty breath, “the up-and-down is ready, and we attach the X.” He had split the end of the stubby plank he had fashioned, and now he wedged the short length of broken ax handle into the split so that the cutting edge of the ax was at right angles to the plank.

Muskrat looked up at the tree he had chosen, an aspen not far from the edge of the pond. The tree was two feet thick, and the gray trunk towered sixty feet up into the clear sky. He took the little plank with the ax head and balanced it like a seesaw on a rock so that the cutting edge rested against the tree. Then he tied a stone to one end of the plank to weight the ax head, and another heavier stone at the other end for a counterweight.

Now when Muskrat touched the plank, the ax head lifted, and when he let it go it came down and bit into the tree with a satisfying CHONK. “There,” he said. “It just goes up and down like that until it gnaws down the tree.”

“What will make the X go up and down?” asked the mouse child.

“You will,” said Muskrat, “and I must say that I envy you your part in this.” He tied a long piece of string to the end of the plank, then led the string under a forked twig that he stuck in the snow like an upside-down Y. He tied the free end of the string to the mouse father’s arm, and he scooped out an oval track in the snow for the mouse and his child to walk in.

“Are you ready?” said Muskrat.

“Yes,” said father and son together.

Muskrat wound up the father, and the mouse and his child walked around the oval track in the snow. The forked twig acted as a pulley for the string, and as they walked away from the tree the plank tilted to lift the ax; as they walked back toward the tree the ax fell with a CHONK.

“Well,” said Muskrat. “Why times How will, in time, equal What. There we are. That’s it!”

“How long will it take to fell the tree?” asked the mouse child, backing around the oval as his father pushed him.

“Let me see,” said Muskrat. “This is late winter, and the tree is about thirteen X’s around the trunk. Once around the track equals once up and down equals CHONK!” His voice trailed off into a low mumble as he calculated. “We’ll get it done by late spring,” he said. “Easily.”

“Late spring!” said the father. “Does it take the beavers that long?”

“No,” said Muskrat. “But of course they have the tools, you see, and we must use makeshifts.”

“What a long time to walk in a circle!” said the mouse child.

“It’s an oval,” said Muskrat. “Don’t think of the walking. Think of the crash; think of the splash; think of the ever-widening ripples!”

The mouse and his child walked steadily around the oval while the ax rose and fell, its blade biting into the tree with a CHONK, CHONK, CHONK that sent echoes ringing across the pond. As they walked the muskrat moved the plank and the rock closer to the tree, so that the ax progressively bit deeper; and when the cut was well started he moved the whole apparatus around to a new part of the trunk. Then he made a new oval track in the snow for the mouse and his child.

“Do you suppose,” the father asked Muskrat, “that while we walk you might begin to think about self-winding?”

“Ah!” said Muskrat. “That’s not pure thought, you know; that requires some tinkering. I can’t consider the Hows and the Whats of your clockwork without taking you apart; and I can’t take you apart until we’ve finished our work here.”

“In the late spring,” said the father.

“That’s right,” said Muskrat. “But the time always passes quickly on an exciting project like this. You’ll be done before you know it.”

He looked up as the blue jay reporter passed overhead, circled, and came back. “Very good,” said Muskrat. “Our work has already begun to attract attention. Good morning!” he called to the jay. “I’ll be happy to give you a brief statement.”

“Later,” said the reporter. “I have a lot of ground to cover.”

“Have you seen an elephant or a seal?” called the child.

“Don’t remember,” said the blue jay. “MUSKRAT, WINDUPS ACTIVE IN WINTER SPORTS,” he announced in a less than front-page voice, and flapped away.

* * *

DAY AFTER DAY the muskrat and the mouse and his child worked at the tree, until the overlapping oval tracks radiated from the trunk like the petals of a flower, and in every oval the tin feet of father and son had worn away the snow until they walked on the bare earth.

While Muskrat’s project trudged ahead, the life of the pond went on as always: The beavers were busy in their lodge with production plans for spring; the fish moved slowly in the dark water beneath the ice; and turtles, snakes, and frogs slept through the winter in the mud at the bottom. On the shore the chipmunk and the groundhog slept the season out in burrows down below the snow, while the wood mouse and the rabbit foraged through the frozen nights, pursued by owl and fox and weasel. High in the glittering sky Orion the Hunter shone down on the hunted who ran their nightly race and left their tracks for each day’s morning sun to see, a record in the snow of who had lived and who had not. Above the mouse and his child waxed and waned the icy moon, and bright Sirius kept his track across the sky while they trod theirs below.

And beyond the beaver pond the world went its way. The Caws of Art decided not to attempt The Last Visible Dog again that season. Having lost both their rabbit and their repertory, they recruited a stagestruck opossum and patched together a revue with which they continued their tour. In the meadow and along the stream new regiments of shrew soldier-boys marched and drilled and took up arms for territory. At the dump the broken carousel still played, and rats caroused along the midway as before. The dollhouse, ravaged as it had been by a nursery fire that started when its youthful owners played with matches, became in its romantic ruined state a trysting place for young rat lovers, then a social and athletic club. Of the ladies and the gentlemen all that remained was the globe the scholar doll had had beneath his hand, and that was now a football for the rats. Elsewhere in the dump the gambling dens and dance halls prospered as before. The sexton beetle and other small businessmen enjoyed full profits for a change, and trade throve unassisted, for Manny Rat had not returned to claim his share. His forage squad stood leaderless in rusting immobility, and at the beer-can avenue’s end his television cabinet gaped emptily at the distant fires.

Starting from the pine woods where the weasels had given up the chase, the frustrated rat, bitten, torn, and generally smarting and stinging from his theatrical debut, went back to where he had last seen the mouse and his child. From there he cast about in ever-widening circles, but found no track or trace of them. He was sorely perplexed and troubled, and growing ever more doubtful of the quest to which he found himself committed. It had begun simply enough: Two tin mice had made a fool of him, and he, in order to maintain his self-respect, was bound to smash them. Then, just as the whole affair had reached the point of final resolution, the frog had made a fool of him again, and had taken off his rightful victims with the shrews. By then it had become clear to Manny Rat that nothing was simple anymore, but sheer tenacity had driven him upon his third humiliation, in the role of Banker Ratsneak.

He grew morose, and felt himself half overcome by funk. Why must he go on pursuing clockwork mice, he asked himself. Why must he travel all the night, and sneak through thorns and brambles in the daylight, studious to avoid the blue jay’s eye? And what would his reward be at the end? By the time he smashed these trumpery windups his name would be forgotten at the dump, his enterprises taken over by younger, upward-moving rats. The frog’s words came into his mind: “A dog shall rise; a rat shall fall.” Were dogs to track him down?

But Manny Rat had no choice left; some force beyond himself was pulling him whichever way his quarry turned. He wound the elephant, cursed forlornly at the now-empty provision bags she carried, and shuffled on as if at the end of an invisible chain by which his prey would drag him to his doom.

And in another part of that world beyond the pond, high in a hickory tree, in a leafy squirrel nest into which he had providentially fallen when he slipped out of his woolen glove and the horned owl’s talons, the frog, under a kind of polite duress that amounted to house arrest, told fortunes night and day, and begged the squirrels to help him down and on his way.

The mouse and his child worked through the winter rains and snows while Muskrat hovered near to wind and oil them and to shift his tree-cutting machinery as necessary. The project was interrupted only when hunger or fatigue forced him to abandon briefly the world of applied thought for the physical refreshment of the thinker. Lessons were suspended indefinitely, and the young muskrats of the pond enjoyed a holiday, while father and son walked their ovals night and day. Sometimes the work stopped when a storm buried the mouse and his child in snow, and Muskrat had to dig them out; sometimes the father’s clockwork froze, and Muskrat would take him and the child back to his den until they were warm enough to work again.

Most of their fur was gone by now, and what was left was long past mildew, and sprouting moss. Their whiskers were blackened and draggled; their rubber tails had lost their snap; their glass-bead eyes were weatherworn and dim, and the last shreds of the blue velveteen trousers flapped forlornly about their legs. The father’s motor, so often wet in rain and snow, had stiffened somewhat despite the oiling. Pushing his son backward around the track, he walked more slowly than before, his eyes fixed on the coin that swung from the child’s neck with the drum.

“That coin grows heavier each day,” he said. “It’s hard enough to keep going without pushing any additional weight.”

“It belonged to Uncle Frog,” the child said. “Maybe it will bring us luck.”

“It didn’t bring him luck,” replied the father. “And in any case, I fear that we shall soon be beyond the reach of any luck that may be forthcoming. At this rate our motor will be quite worn out long before we attain self-winding.”

A white mist rose up from the melting snow; the ice had vanished from the pond; the water shivered in the chilly air. The dark earth reeked of spring; the oval tracks were scored in mud. The calling of the crows upon the east wind had the sound of winter’s passing. High overhead there flew two northbound Canada geese. Their honking seemed to fall in silent, frozen crystals of encapsulated sound that melted on the warming earth below, releasing, quiet, small, and clear, the voices and their message. The geese swung low, turned upwind, landed on the pond, and rocking on the water, moored to their reflections.

Onward walked the mouse child, backward, in his oval track that was only the old and endless circle made more narrow. He followed his own footsteps going nowhere, his one reward the tension of the string as he moved outward from the tree, the chonking bite as he returned to see the ax blade fall again. The thick base of the aspen, marked by thousands of ax strokes, tapered sharply inward to the point on which it balanced.

“Soon!” said Muskrat. “Very soon now, our project will reach completion. I must plan the final X-strokes so the tree will fall with maximum splash.” He looked about him moodily. “Then, perhaps,” he said, “there’ll be some notice taken.”

Certainly very little notice had been taken so far. The animals around the pond were fully occupied in living, dying, or waiting, dormant, for the spring. Only the birds had time to watch the project: Chickadees told one another to come and see, see, see; cardinals whistled sharply at it; and nuthatches, upside down and busy pecking for grubs on the aspen trunk, said, “Ha, ha,” as the ax strokes rang out on the cold air.

“You may laugh,” said Muskrat to a nuthatch, “but you’ll see something soon.” He retired to his den for lunch, and the mouse and his child, left to themselves, walked their track until the father’s spring ran down.

“It must be soon,” the father said. “We have been patient for a long time.”

“And then, self-winding!” said the child, and as he spoke he saw two dark figures in the white mist rising from the melting snow. Passing into and out of sight among the bare, black trees and stumps, they came toward the mouse and his child.

Manny Rat still bore the scars of his brief thespian career, and his paisley dressing gown hung all in tatters. He was thinner and sharper-looking than before, and seemed to be thrust forward through the fog by all the darkling midnights that had brought him to this gray and misty morning. He bent to the trail with such concentration that he did not see the father and son until he was almost upon them. Then he lifted up his head, and his smile was that of someone who, after long and painful separation, finds his dearest friends.

The elephant moved slowly. Nothing had been able to force a daytime word from her, nor did she any longer speak between midnight and dawn; in silence she plodded at her master’s heels and endured her shame. What was left of her blackened plush was streaked with rust; her one ragged ear had heard no good word for a long time; her one glass eye looked out at life askance.

“Look!” said the child. “The elephant! We’ve found her, Papa!” He had never been so happy, had never felt so lucky. He had never doubted that he would make his dream come true, and all remaining difficulties shrank before him now — the dollhouse and the seal would certainly be found, the territory won, and he should have his mama. And then it came to him that Manny Rat was there to take away the whole bright world and smash him.

The elephant was completely overwhelmed. Until now she had thought only of herself and the injustice done her; the child and the father had been nothing to her. But now into her one glass eye there rushed the picture in its wholeness of the foggy day, the steaming snow, the black trees, the tired father, the tiny, lost, and hopeful child. A world of love and pain was printed on her vision, never to be gone again.

The father could not find a word to say. The sight of the elephant and the rat flashed upon him with such intensity that he seemed to hear the seeing of them; his ears crackled and roared, and the two figures expanded in the center of his vision while all else blurred away. The elephant was shabby and pathetic; her looks were gone, departed with the ear, the eye, the purple headcloth and her plush. The father saw all that, and yet saw nothing of it; some brightness in her, some temper finer than the newest tin, some steadfast beauty smote and dazzled him. He wished that he might shelter and protect her, and all the time he saw the rock uplifted in the paws of Manny Rat. He fell in love, and he prepared to meet his end.

Manny Rat sighed with immense relief as his world spun out of chaos into order once again. Large ease and happiness were his once more; the headache that had plagued him recently was gone. He drew closer with his rock, but his curiosity for the moment overcame his desire to smash the nightmarishly durable father and son. “Winter sports, eh?” he said. “What in the world are you doing? It’s absolutely fascinating. Good heavens!” he said. “You’re chopping down that great, enormous tree. What a crash that’ll make when it goes! How much longer do you think it’ll take?”

“What does it matter now?” said the father.

“I must see the outcome of this,” said Manny Rat. “Let’s speed things up a little.” He put down his rock, seized the string that was tied to the father’s arm, and ran full speed around the track, dragging the mouse and his child along with him while the ax struck faster and faster, its echoes ringing out across the pond.

A long shiver ran up the gray trunk of the aspen to the topmost branches bare against the sky. Slowly at first, then faster, leaving empty sky behind it, the tree leaned earthward with a rending groan, tore one by one its final splinters loose, and fell.

Muskrat had intended to direct the last strokes of the ax so that the tree would fall into the pond in a place where no damage would be done. But now as the aspen toppled it struck a taller tree that had been split by lightning, which fell in turn against a giant that stood dead and rotting at the water’s edge. One after another they crashed and fell, and the last one landed squarely on the beaver dam and smashed it. A great splash went slowly up into the air as the saplings were scattered like matchsticks and the waters of the pond poured out into the valley.

The Canada geese took off in a flurry of great beating wings as the water rushed away. The beavers shot out of their lodge, surfaced in a welter of broken twigs and splintered branches, and grasped the situation at once. “There goes the pond!” they yelled. “After it, men!” Jeb and Zeb, drawn backward in a foaming rush of water, shouted, “No more school forever!” as they shot the falls, while startled fish on all sides cried, “The world has sprung a leak!”

The pure-and-applied thinker, dining underground in his den, felt the earth shake. The fireflies went dark with fright, and Muskrat, stumbling through the clutter, limped up to the daylight. The sun had come out through the overcast to burn away the morning mist. The sky was clear; the air was soft with spring. He looked out on a broad expanse of rank-smelling mud, debris, and matted grasses by a tiny, trickling stream where once the pond had been, and while he stood and gazed, the blue jay, passing overhead, called down, “What’s new?”

Muskrat pointed to the desolation. “Why times How equals What,” he murmured.

“Pond minus Dam equals Mud,” replied the jay as he flew off. “That’s not news.”