“NO PEACE,” said the bittern as he stomped home through the bogs. “No quiet. No privacy whatever. The world is constantly at one’s door, chattering and squeaking and demanding to be wound up.”

He sighed and went back to the frog pound he had been building before the voices of the mouse and his child had distracted him. Well hidden in the marsh, an unfinished fence of stakes driven into the mud defined an enclosure which, when complete, would provide a place where his dinners might be kept fresh until such time as they were needed.

The bittern approached the stake at which he had left off, jumped onto the flat rock he had been using as a mallet, grasped it firmly with his toes, beat his wings, and lifted the rock as he raised himself into the air. OONG! He grunted, and brought the rock down on the stake. BONK! Then he let his breath out. CHOONG! He repeated the process, pumping and thumping like a small pile driver as the rock went up and down steadily until the stake was driven in among its fellows.

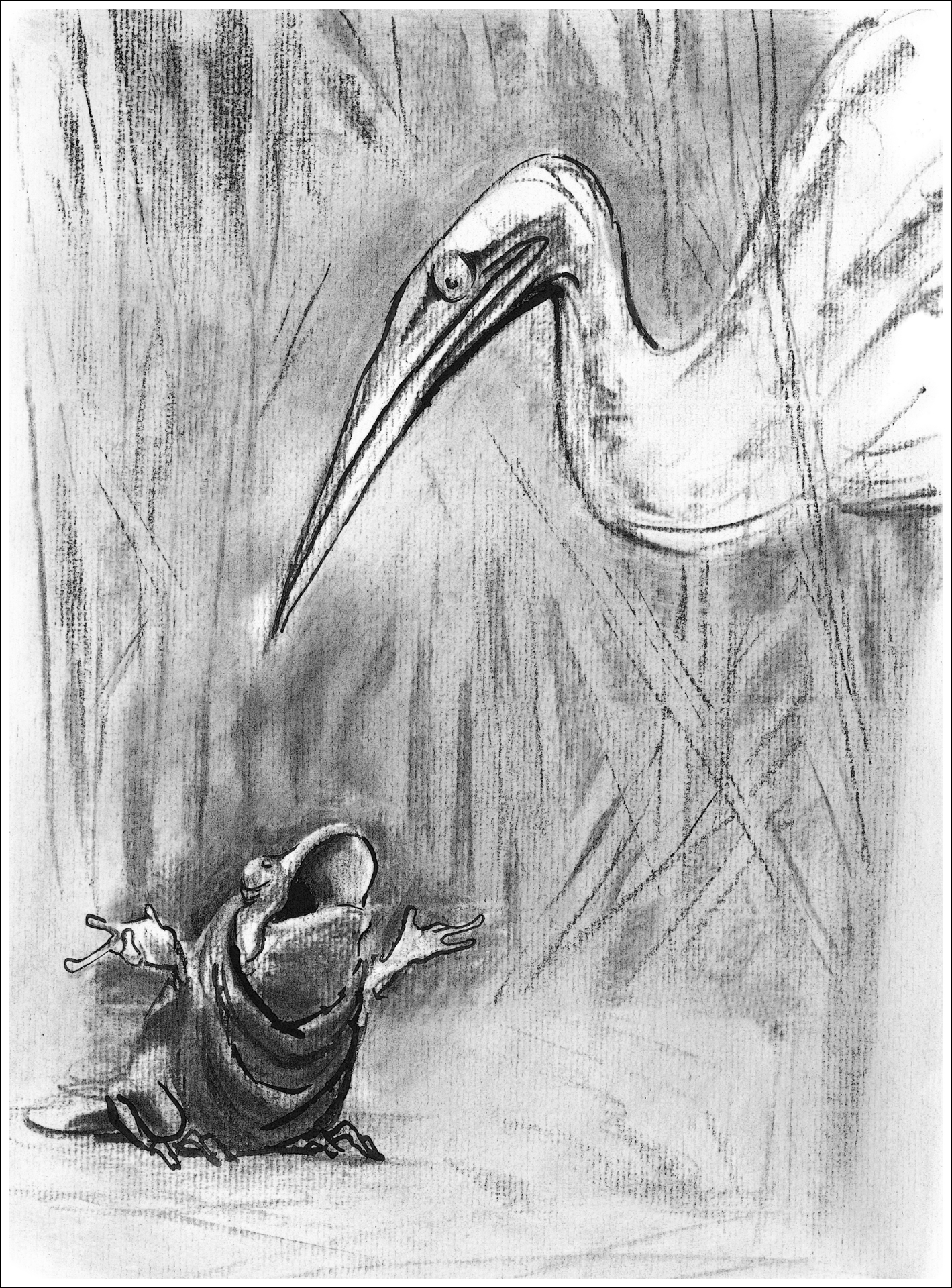

When the fence was complete and the frog pound ready to be stocked, the bittern waded off, his shoulders bunched, his neck in a flattened S-curve, and his long, sharp beak moving crankily forward and back with each step. In a few minutes his little yellow-spectacle eyes brightened as he came upon a large bullfrog, wearing a grease-stained canvas work glove, who sat on a tussock and stared open-mouthed at that part of the sky where the marsh hawk had just passed overhead.

The bittern pointed his beak straight up and swayed invisibly among the reeds while his downward-looking eyes examined the frog minutely. Having judged from the plumpness of the glove that the bullfrog was sufficiently tender for the evening meal, the bittern was about to dart his beak forward at his prey when it spoke.

“STOP!” roared Frog. “DESTINY IS NOT TO BE TRIFLED WITH. DO NOT COMMIT THE TRAGIC ERROR OF SATISFYING PRESENT APPETITE AT THE COST OF FUTURE FULFILLMENT.”

“What’s that you say?” asked the bittern, drawing back in alarm.

“AH, MY FRIEND,” bellowed Frog, puffing out his yellow throat and blowing himself up as large as possible, “TO HOW MANY OF US IS GIVEN THE OPPORTUNITY OF SEIZING THAT PRICELESS MOMENT IN WHICH THE TANGLED THREADS OF MINGLED FATES CAN BE UNSNARLED AND WOVEN, WARP AND WOOF, INTO THEIR PREORDAINED DESIGN!”

“What?” said the unnerved frog-stalker. “Where? Warp who? Woof what?”

“QUICKLY!” boomed Frog, “FOLLOW THAT HAWK, AND TAKE ME AS YOUR PASSENGER.” Even as he spoke he rapidly wove a little sling of reeds in which the bird might carry him. It had taken him a long time to find a new glove, and he was taking no chances on slipping out of this one. “DESTINY DOES NOT WAIT,” he said. “MAKE HASTE! I SHALL EXPLAIN ALL AS WE TRAVEL.”

* * *

THE BASS that had swallowed the good-luck coin swam back to his nesting hollow, the line trailing behind him until the drum caught on a root. Then the knot that tied it to the coin came undone, the line slid out of the fish’s throat, the nutshell drum bobbed once more to the surface, and the bass was free. “Not bad,” he said with a chuckle as he felt the coin’s cool smoothness in his stomach. Highly satisfied with himself, he tidied up his little hollow, patrolled its borders aggressively, inquired of the neighboring bass whether there had been any messages, then swam off in search of new adventure.

He found it in a quiet corner of the pond, where slanting sunlight came down in long rays through the shadows of the leaves, and something shiny was descending slowly through the water. It was the tin seal at the end of a fishing line, wiggling her tail and flapping her flippers.

The metal rod that once had held the ball was now ornamented with bright feathers that slowly and seductively revolved. Several fishhooks dangled below the feathers, and the seal’s worn tin glinted in the green-lit water. Like the mouse and his child, she had long ago broken the clockwork rule of daytime silence, and now she sang softly, as if to herself:

Just a little lonely maybe,

Thinking of you only, baby.

“Holy smoke!” said the bass. “Look at that action!” Churning the water as he worked up speed, he struck, hooked himself, and with the seal, was hauled up out of the pond to the branch of the birch tree where the kingfisher sat. Beside the bird was a string bag that contained his fishing equipment: spare hooks and lines that he had salvaged and a little can of oil with which he kept the seal in operating condition.

“Good work!” said the kingfisher. Stocky, handsome, and sporty looking, with an honest beak, a frazzled crest, and a friendly eye, a bachelor whose love for solitary fishing trips had kept him from ever settling down, he found the tin seal both a charming companion and an efficient helper. He took the bass from the hook and clubbed it to death on the branch. Then he coiled up his line, oiled the seal carefully, and cleaned the fish, putting the coin, when he found it, into the string bag. Then he sat down and enjoyed a hearty lunch.

“Funny thing happened while you were underwater,” he said to the seal. He described the emergence of the mouse and his child from the pond, their winding by the bittern, and their subsequent capture by the hawk.

“Two windup mice,” said the seal. “Was one big and one little? Blue trousers? Patent leather shoes?”

“One big and one little,” said the kingfisher. “Their pants might have been blue a long time ago. No shoes —”

Noticing the nutshell drum floating on the pond below him, he interrupted the conversation to fetch it and add it to his kit.

“Two windup mice,” the seal repeated. “I wonder if they’re the same ones I used to know.” She remembered how the child had cried, not wanting to go out into the world. “Which way’d the hawk go?” she asked.

“He was heading for home,” said the kingfisher. “He lives in the swamp on the other side of the dump, across the railroad tracks.”

“He can’t eat them,” said the seal. “I wonder if he’s dropped them?”

“If he has, we’ll probably hear about it on the Late Sports Final,” said the kingfisher. “Feel like flying over toward the swamp for a look around?”

“Let’s,” said the seal. The kingfisher packed his gear, put her into the string bag, and they took off.

* * *

WHILE THE KINGFISHER and the bittern were following the marsh hawk, another bird was ahead of them, hot on the same trail: The blue jay too had seen the harrier and his prey. Avid for disaster and eager for a headline, he pursued his story at top speed, and was in time to see the mouse and his child fall. The blue jay’s shadow glided over the child’s broken face as the reporter circled low for a close look at the wreckage, then soared up on the warm air from the fires.

“LATE SPORTS FINAL!” he screamed. “WINDUPS CRASH IN DUMP. NO SURVIVORS.” The jay scanned the immediate vicinity for late scores, yelled, “DUNG BEETLES BLANK ROACHES IN FIRST GAME OF DOUBLEHEADER,” and flew away, leaving behind him silence broken only by the crackle of the flames in the burning trash.

The kingfisher heard the news, and altered his course to head toward the sound of the blue jay’s voice. The frog heard it, and urged the bittern to fly faster. Manny Rat heard it too. He had been looking up at the sky, impatient for the dark, when he saw the hawk drop something over the dump, and now he kept his eye on the spot marked by the blue jay.

“Iggy!” he called, and Ralphie’s successor, an equally ill-favored young rat of stocky build and no scruples whatever, hurried to his master’s side.

“What’s up, Boss?” said Iggy.

“Get over to the ridge on this side of the fires,” said Manny Rat, “and see if you can find a couple of windups.” Iggy saluted and shuffled off as directed.

“It couldn’t be those two,” mused Manny Rat aloud. And yet he was disquieted; his heart was beating faster, and his head began to ache a little. Months ago, on his return to the dump, he had let it be known that the fugitive windups had been brought to a final accounting after a long and arduous chase, and the reaction of the general public had been one of heightened respect for him. Was he to be made a fool of once again, he wondered? Anxiously he watched the departing figure of his lieutenant, and looked beyond him to the distant tin-can ridge. “No,” he said again, “it couldn’t be those two. But on the other hand, who else would drop out of the sky like that?” He frowned, and looked across the rubbish mountains to the setting sun.

* * *

IGGY WAS STILL several trash piles away when first the kingfisher, then the bittern, landed, stirring up a little cloud of ashes around the debris of the mouse and his child.

“We’re too late,” said the seal after the frog had hastily introduced himself and the bittern. “I’m afraid this is the end of them.”

The frog said nothing, but quickly gathered up the clockwork and the parts of the broken tin bodies and put them into the kingfisher’s string bag. Then both birds took off with their passengers and flew to the edge of the dump, where they perched in an oak tree near the railroad tracks and considered what to do next.

“Now that I have assisted you with your warps and woofs,” said the bittern to the frog, “I really must return to my usual mode of life. Good-bye.”

“Good-bye,” said Frog. “On behalf of my friends and myself, let me offer our heartfelt thanks for your prompt and generous response to my appeal for help.” But the bittern, his farewells completed, stayed where he was, looking at the broken father and son.

“I hope we’ve got all the pieces,” said Frog. He took the arms and legs and the two halves of the mouse child, and fitted them together, bending the little tin flaps back into place along the edges of his body so that the child would not immediately fall apart.

As his two halves came together the mouse child returned to himself. He heard all at once the rustle of the leaves around him, and saw, reflecting the light of the setting sun, the golden eyes of his old friend fixed anxiously upon him. “Uncle Frog!” he said. “I saw you following the hawk; I knew you’d find us before Manny Rat did.”

Frog set him down carefully on the branch and picked up the father. The mouse child had not yet seen the others around him; standing alone, and a little giddy without his father’s hands supporting him, he was looking straight ahead out through an opening in the leaves. “Ours!” he said suddenly and fiercely. “Our territory!”

“What’s he talking about?” said the kingfisher. Then he peered out through the leaves and saw what the child saw.

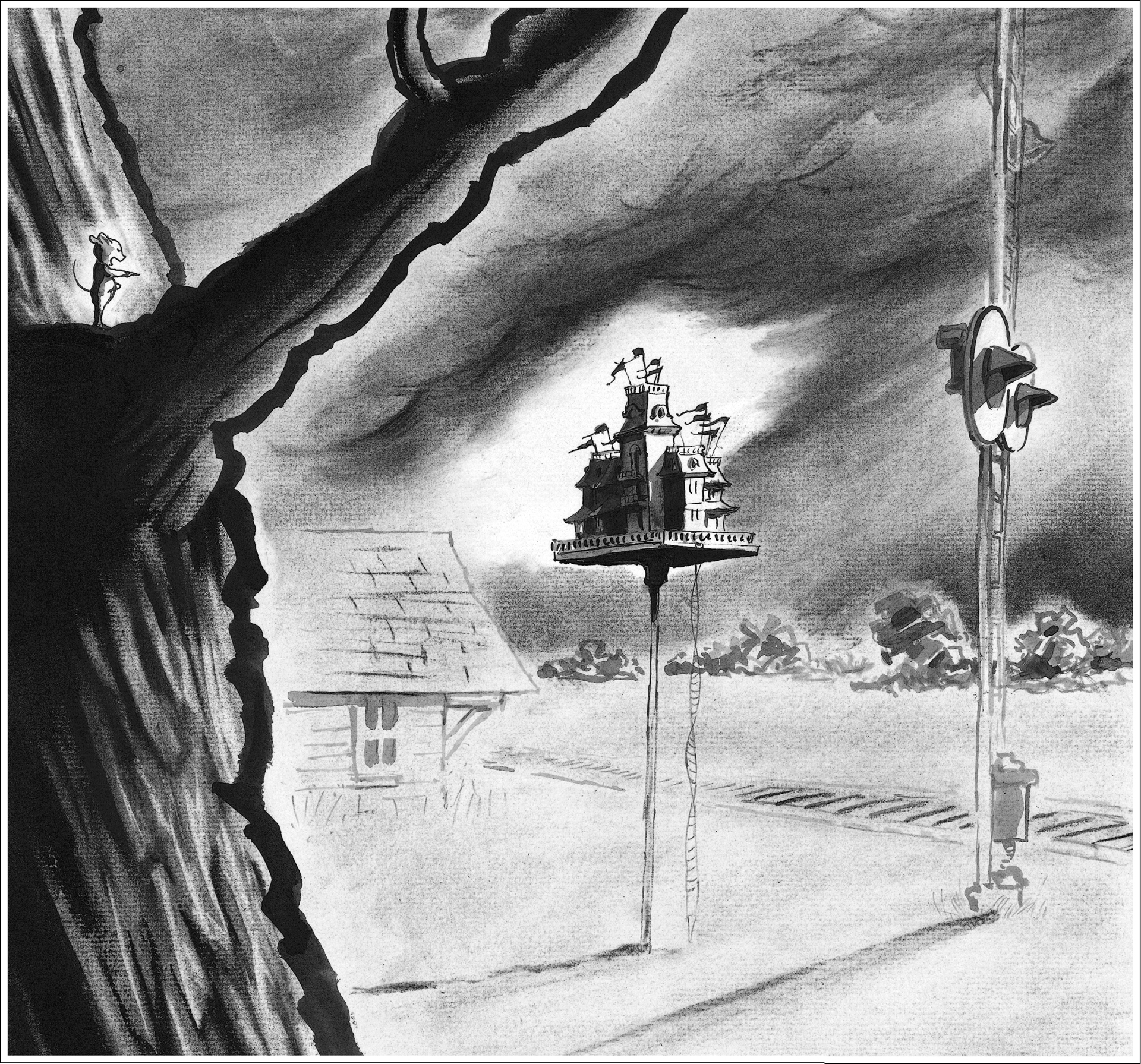

Between their tree and the railroad tracks stood a little cottage, long abandoned. Its paint had flaked away, the empty windows stared out blindly at the tracks, and tall weeds choked the doorway. Beside the cottage was a pole with a wooden platform at the top of it. A large birdhouse had once stood there for purple martins to nest in, but it was gone now. Stark against the red sky, its mansard roof crudely mended with tin and all its chimneys and dormers jammed roughly back in place, was the dollhouse that had been on the counter in the toy store years ago.

The windows had not a pane of glass among them; thick pieces of wood, fastened askew, replaced the ornate moldings and the graceful balusters and brackets of porches and balconies. The scrollwork and the carven cornices were gone, and the whole house bristled with bent nails clumsily driven and smashed into the splintered wood. Nothing was straight, and everything awry. Newly fitted to the roof in place of the lost lookout was a crooked watchtower. The hinged front that had once swung open to reveal the interior was nailed shut, and a heavy coat of black paint covered all. Secondhand crepe paper bunting, the red, white, and blue of which had run together in rain and damp, festooned the balconies, and little faded flags drooped from the chimneys and the tower.

A clothesline pulley fastened to a branch above the roof showed how the house had been raised; a partly filled sherry bottle hanging from the boom of an Erector Set crane hinted at a party; and pacing on the watchtower, in a new silk dressing gown, was Manny Rat. Silhouetted against the sunset, the present master of the dump gazed at the distant trash fires and hummed a little tune while he thought with pleasurable anticipation of the housewarming he planned for that evening.

On his return to the dump after his long absence, he had quickly seen the house’s possibilities as a private residence, and as quickly had preempted it. The ambitious rat, as he expanded his operations with the fullness of time, had become a considerably more important personage than before: He now commanded squads of rats as well as windups, and he had begun to think of the dignity of his position. The trash piles were constantly changing; the television set where he had lived no longer commanded any view whatever. Manny Rat resolved on a dwelling appropriate to his rank, and a location a little removed from the hurly-burly, where he might relax after the cares of the night while yet keeping an eye upon his business interests. Accordingly he evicted the social and athletic club then resident and devoted his ingenuity to the relocation and restoration of his new property. Press gangs of smaller, weaker rats had toiled to raise up and repair the house; the windups of the forage squad had trudged heavy-laden for miles with the materials for its renovation. And the elephant had been harnessed to the crane and windlass so that she might help to put in good order for her master the house she once had called her own.

She stood beside it now, bereft of any plush, her bare tin weather-stained and rusty, her clockwork all but worn out in the service of Manny Rat. Through a glassless window her one eye saw the room in which the lady and gentleman dolls had sat at their tea, where now a garbage buffet set out upon the floor awaited the delectation of the invited rats. Rat servants scuttled up and down stairs, making all ready for the evening, while rat guards armed with spears walked the platform, favoring the elephant with low humor and coarse remarks as they made their rounds.

* * *

THE FATHER was hastily put together as the son had been, and speechless with relief, he looked into the face of the frog. Then he saw the elephant and the dollhouse. “Oh!” he said, and “Oh!” again, and wept. Then he felt a great rage growing in him, and he said the same words that the child had spoken: “Ours!”

“Look, Papa!” said the child as the frog moved the tin seal to where the father and son could see her. “The elephant, the seal, and the house. It wasn’t impossible! We’ve found them all!”

“And the enemy who awaits us at the end,” said the father, watching Manny Rat upon his black tower. He was silent for a little while. Through the gathering dusk he looked at the forlorn elephant standing by the dollhouse. The road had been long and hard indeed, but now he knew that he had found what he had wanted to find at the end of it. “Now we must fight for our territory,” he said.

“I don’t understand,” said the seal. “Kingfishers have territories, and I know that animals do. But toys don’t.”

“We aren’t toys anymore,” said the father. “Toys are to be played with, and we aren’t. We have endured all that Frog foretold — the painful spring, the shattering fall, and more. Now we have come to that place where the scattering is regathered.”

“What do you mean?” asked the seal.

“Be my daughter,” said the father.

“Be my sister,” said the child. “Will you, so we can have a family?”

The tin seal, her hooks and draggled feathers drooping about her head, sat on the branch and looked at the darkening sky. Her past life came back to her all in a rush — the store, the house she had gone to and the children who had broken her, the dump and Manny Rat, her travels with the Caws of Art and the rabbit’s flea circus, the quiet days with Muskrat, and her daily work with the kingfisher. On the whole it had not been a bad life, and yet it seemed a long and weary time that she had been alone of her kind in the wide world. She hesitated no longer. “Yes,” she said, “I will.”

“Well,” said the bittern, “it simply is not possible to put off any longer my return to the marsh; I must seek solitude again.” But still he watched and listened curiously, and made no move to go.

“Have you any plan for winning this territory you claim?” Frog asked the mouse and his child.

“Not yet,” said the father.

“I made the hawk drop us here when I saw you following us,” said the child to the frog. “But I never expected that we’d find the dollhouse and have to fight Manny Rat so soon.”

“As well as seven or eight other rats that I counted in and around that house,” said the bittern, dropping all pretense of leaving, and throwing himself wholeheartedly into the conversation. “And all the guards, as you may have noticed, are armed.”

“Still,” said the kingfisher, “someone with a sharp beak, flying fast and striking accurately, might have a sporting chance.”

“Doubtful,” said Frog. “Very doubtful.”

“There’s Manny Rat all alone on the tower,” said the kingfisher, “and without a spear. What if I got through the guards and finished him off right now?”

“Then all the other rats would move up one,” said Frog, “and there would be a new Manny Rat to finish off.”

“You’re absolutely right,” said the father. “It isn’t simply a matter of killing one rat or winning one battle. That battle must be won in such a way as to inflict upon the enemy a defeat so crushing that every rat in the dump will live in abject terror of us and leave us undisputed masters of that house. Only in that way can we keep our territory once we take it.”

“And relying as we must upon the element of surprise,” said Frog, “we cannot afford a single wrong move from the very first moment we show our hand.”

“Exactly,” said the father. “The elephant of surprise. Element,” he corrected himself.

Frog looked out through the leaves into the twilight. Thirty feet away, on the dollhouse platform, the rat guards walked their posts in a sloppy and unmilitary fashion, but seemed quite alert. “I find myself wondering about those spears,” he said.

As if in answer to his question, one of the guards idly took aim at a swallow that skimmed low over the dollhouse in the dusk. The bird was an easy target, but the rat’s marksmanship was poor; the spear barely penetrated a wing covert before it was shaken loose. The guard watched complacently as the scarcely wounded swallow flew up sharply, fluttered brokenly a moment, then dropped like a stone. The guard took another spear from a rack and resumed his rounds.

“Poison,” said Frog. “Just as I feared. Friend Rat has learned something from the shrews.”

“What do we do now?” said the kingfisher.

“Wait,” said the father.

“For what, exactly?” asked the bittern.

“I don’t know,” the father said, “but I’ll know it when I see it. Something will happen; some sign will indicate the X for us. My son and I have been a long time waiting; we can wait a little longer now that victory is close.” His eyes were fixed on the elephant as he spoke, and there was new energy in his voice.

“How can you be so sure of winning?” asked the seal.

“We have already done our losing,” said the father. “Our defeats are all behind us.”

Night fell, and a new moon, having risen early, showed its thin yellow crescent now declining in the west. The oak leaves pattered, and with the shifting night breeze came the faint sound of the town hall clock as it struck eight. A dim red glow, as always, lit the sky above the dump, and the sounds of evening, ascending one by one, merged in a general hum and clamor. The carousel played its cracked waltz on the rats’ midway; the gambling booths, the gaming dens and dance halls came noisily to life, then disappeared with all their mingled voice into the lonesome wail and rumble of a passing freight. Above the tracks the green and red lights on the gantry clicked and changed; the engine’s headlight slid along the shining rails, picked out leaf and branch and dollhouse where the boss of the dump still paced his tower. The sound grew with the train, as car by clanking car its passage shook the pole and set the dollhouse hottering on the platform. Clacking through the switches went the boxcars, rumbling on until the yellow-windowed caboose and its red lantern dwindled into darkness; the gantry blinked its changes, and the train was gone. An edge of cricket song and silence stayed behind it for a moment in the small and smaller clacking of the rails; then the cracked waltz of the carousel returned, the dance hall’s thumping whine, the distant cries of pitchmen and of vendors in the alleyways and tunnels.

By the starlight and the slender moon they could see nothing clearly, but the little group in the oak tree could hear the guards keep watch with steady thump and shuffle as they walked the platform. Several of the off-duty rats lifted their voices in a bawdy song, and two of the servants were squealing insults at each other in a dispute over some moldy cheese. Father and son listened carefully, focusing their complete attention on every sound in an effort to extract the information that would give them a plan of attack.

There was a clink and rattle in the weeds at the bottom of the pole. Someone had stubbed his toe on something, and was cursing softly. “Who’s that?” challenged Manny Rat.

“It’s me — Iggy,” answered his lieutenant. A string ladder rustled as it was let down, and the invisible Iggy climbed up to the platform. A muttered conversation ensued, too low to be audible, and then Manny Rat was heard again, berating his subordinate for his failure to find the fallen windups reported by the blue jay.

The ladder shook again as Iggy descended. They heard him moving about in the weeds, then the unmistakable sound of spring motors being wound up. The forage squad, their collective clockwork set in motion, receded into the distance with Iggy and their song:

Who’s that passing in the night?

Foragers for Manny Rat!

We grab first and we hold tight —

Foragers for Manny Rat!

There was a period of silence in the oak tree. Then the father spoke. “I think a sign has been given us,” he said.

“What?” asked the child.

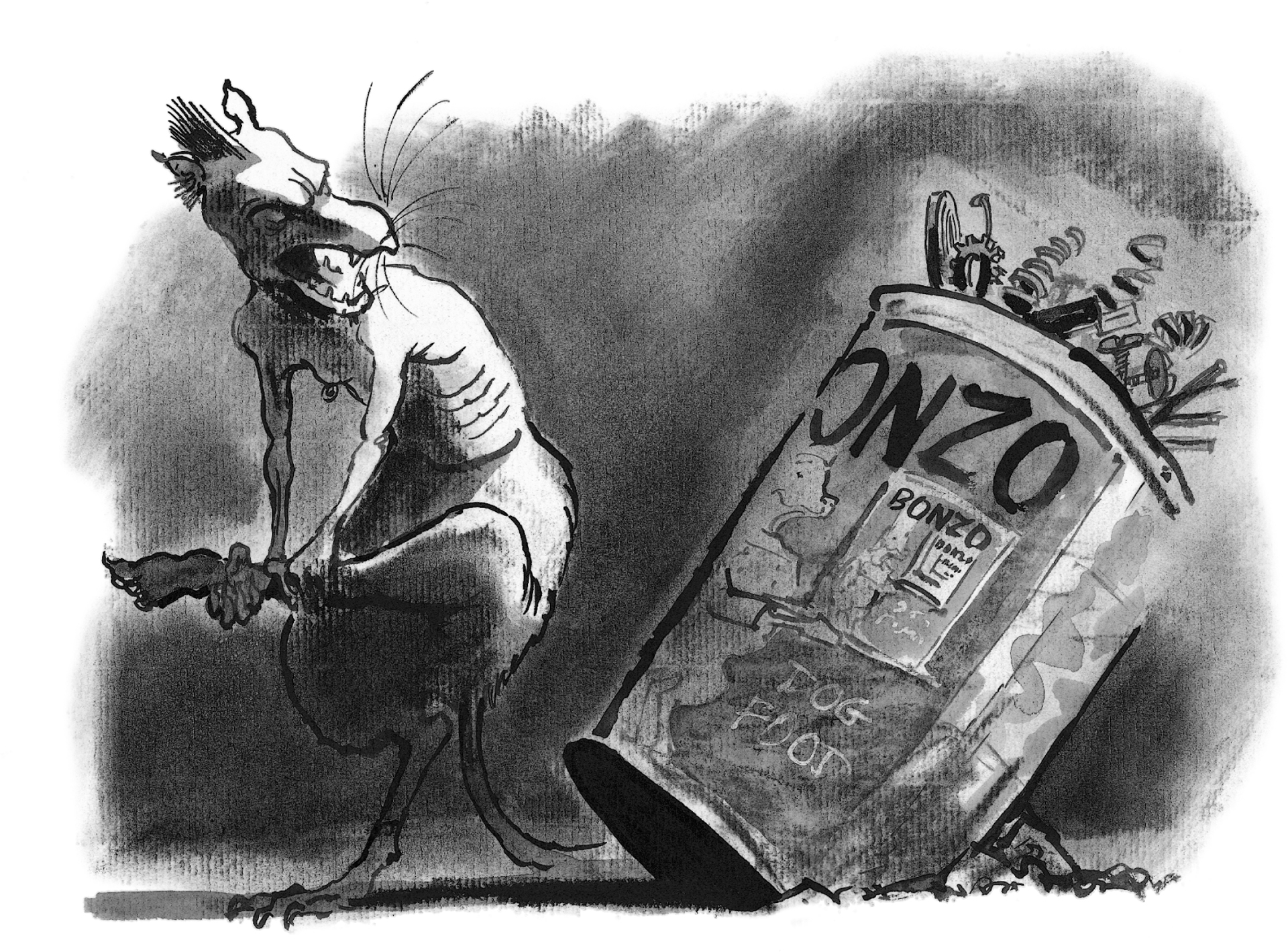

“The same one that has been given all along,” said the father. “The last visible dog.”

“Where?” asked the child.

“On the label of Manny Rat’s spare-parts can,” said the father. “I’m certain that’s what rattled in the weeds when Iggy stubbed his toe. In that can we should find the equipment necessary both for fighting Manny Rat and for self-winding. Now all we need is a plan.”

“I think I have a plan,” said the child. “Did you hear a bobbling sound on the platform when the train went by?”

“Yes,” said the father. “What about it?”

“Manny Rat repaired the house and painted it and put it up on top of the pole,” said the child. “But there’s one thing he hasn’t done yet.”

“What’s that?” asked the father.

“He hasn’t nailed it down,” replied the mouse child.

The moon had set, and Manny Rat’s guests were due to arrive soon. The boss of the dump, awaiting them on the tower of his beautiful new house, stopped his pacing abruptly. Against the background uproar of the dump and the racket of servants and off-duty guards he had become suddenly aware of some unidentifiable sound that was quite close and unspeakably eerie. He strained to hear it again, but it was gone. Manny Rat thought about that horrid sound many times that evening, and when he did, he shivered. But it was only much later that he came to know that what he had heard was the combined hilarity of a kingfisher, a bittern, and a frog, above which rose the peculiar, creaking, squeaking, rattling noise of laughing tin.