Mount Rushmore

Bedrock theories of applied motivation

Motivational Mount Rushmore is reserved for only a few select invitees. Theoretical immortality is based upon creating a set of guiding laws and principles that broadly explain multiplicative aspects of agentic behavior while concurrently withstanding rigorous empirical scrutiny over time. Three enduring approaches that have wide applicability to learning and performance outcomes are theories emphasizing attributions, expectancies, and self-efficacy. Cornerstones of each theory include self-beliefs related to the causality associated with success or failure, the relative worth and value ascribed to contemplative tasks, and the degree of capability associated with achieving desired outcomes. Like many implicit judgments, these cognitive constructions are strongly influenced by the company we keep and where and how we elect to demonstrate our abilities. The next step in the quest to gain motivational self-awareness explores how personal assessments are deeply entwined within our overall social existence.

Keywords

Attributions; self-efficacy; expectancy-value; self-beliefs; social cognitive theory

Thinking back to Chapter 1, you may recall that Reeve (2009) indicated that at least 24 different theories have been empirically advanced to substantiate agentic behavior. A select few theories are conceptualized as the “grand” theories of motivation. The “grand” moniker purports that these theories do more than explain particular influences on behavior; instead, they have expansive explanatory power regarding how people control and regulate their lives. For example, the principle of operant conditioning rooted in behavioral learning theory (see Principle #33, p. 149) and Freud’s Drive Theory (1922) were once thought by many scholars to be consummate approaches to understanding human behavior. Subsequently, each theory has been debunked as all-encompassing: operant conditioning due to minimal consideration of personal beliefs and nuanced reasoning, while psychoanalytic approaches were rejected due to the highly introspective and untestable nature of Freud’s proclamations.

Today, grand theories are historical relics that have acquiesced to prominent mini-theories, which “analyze specific areas of motivated behavior” (Graham & Weiner, 1996, p. 63). Mini-theories typically target one aspect of personal agency, such as goal setting or emotional arousal, and frequently generalize applicability of theoretical premises to specific populations or contexts of application. For instance, we previously learned about the role of self-determination as instrumental in indicating the degree of commitment and type of motivation individuals may exhibit toward a task. Three other prominent mini-theories that provide significant explanatory power and utility to describe learning, achievement, and performance motivation across contexts are the attributions, or causes, that individuals use to account for their academic success or failure; the importance, value, and usefulness individuals ascribe to particular tasks; and the beliefs individuals hold concerning personal effectiveness. Prolific researchers, such as Bandura (self-efficacy), Weiner (attributions), and a host of scholars, including Rotter, and Wigfield/Eccles (expectancy-value), have spawned literally thousands of cross-disciplinary and multi-cultural research studies revealing specific cognitive and affective evaluations originating in personal task beliefs, which are strong predictors of the challenges individuals are willing to pursue, and, ultimately, how and why they are energized to reach their goals.

The common bond among the three iconic theories briefly described above rests upon the defining premises of social cognitive theory, which contends that learning, performance, and achievement motivations are contingent upon a causal and reciprocal interdependence among personal expectations and values, intentional behaviors, and environmental influences. The interdependent phenomena suggest that human behavior is mediated by cognition and reciprocally determined by a series of bi-directional, differentially weighted influences, rooted in human sociocultural interaction. Individuals use a personal framework, akin to a set of rules that they act upon, to accomplish their motivational goals. The relative influence of each pillar of the triadic social cognitive model fluctuates, based upon proactive judgments and the action being contemplated by the individual. As Bandura (1997) eloquently indicated when describing self-reflective action, “people analyze the situations that confront them, consider alternative course of action, judge their abilities to carry them out successfully, and estimate the results the actions are likely to produce” (p. 5). The social cognitive model does not purport to be the sole determinant of individual action but, instead, provides a process of systemic, reflective guidance promoting ongoing appraisals of personal values, situational determinants, and probabilistic outcomes used by the individual to make behavioral decisions. In all cases, individuals see themselves as part of a larger, socially constructed system that is frequently a prevailing influence on behavior.

A practical example of the socially guided nature of reciprocal determination was provided by former National Football League (NFL) star, Guillermo C. “Bill” Gramática. Bill, who as a teenager along with his brothers Martin and Santiago, made the culturally defiant, life-changing decision to give up promising and predictable careers as professional soccer players. Instead, the brothers collectively decided to attempt to make a living kicking field goals despite lack of proven skills and the unpredictable and more dangerous life of a professional NFL football player. When asked about what influenced the decision to leave the relative safety, security, and culturally expected game of playing soccer, Bill stated,

As a kid in Argentina, the first thing you get is a soccer ball and a jersey, and you play ALL the time, you love it so much, it’s a passion. My brother, Martin, was like a father to us; he gave up his childhood for us. I decided to pursue college football instead of soccer because of him. I wanted to be successful, and I wanted to follow in my brother’s footsteps and not disappoint him.

B. Gramática, personal communication, October 13, 2013.

Bill revealed that place kicking was very different from playing soccer, and he was not entirely sure of what would happen upon giving up soccer: yet he decided to pursue a football career in spite of the uncertainty. Bill added, “Whatever it is, you don’t want to go in half-way. I wanted to take it to the next level; I grew up that way. You set a level or a goal and go for it, nothing gets in the way of reaching the goal” (B. Gramática, personal communication, October 13, 2013). Nothing did get in the way of success for Bill or Martin, as both become highly decorated, record-holding college field-goal kickers. The brothers went on to be Pro-Bowl–caliber NFL stars: Martin playing for over 10 years, including playing in a Super Bowl game, while Bill’s career was cut short after 4 years by a series of debilitating injuries.

We can quickly detect the social influence of Bill’s family upon his career choices. Bill was primarily motivated by his desire to model his older brother’s behavior and show Martin that his fraternal guidance was instrumental in his choices. A closer examination of Bill’s remarks reveals that a series of beliefs about success, goal setting, and contextual evaluations were also part of his career decision. Bill was initially skeptical that his soccer skill could be transferred to football, but he was willing to take a calculated risk and attempt place kicking based upon his past performances and highly successful soccer playing. In other words, Bill questioned the outcome he might realize based upon his existing skill, his perceived athleticism, and his focused drive and ambition. His decision, in part, was based upon evaluating his own competency strivings and the extent of feeling confident and capable about past performances. Further, Bill surmised that a kicking career was potentially lucrative, but he worried about the added risk of injury. Despite his physical trepidation, Bill was willing to assume the risk of career transition because of the potential notoriety and payoff associated with being a Pro-Bowl–caliber NFL football player. Finally, we can see from Bill’s reasoning that environmental factors, although a consideration, were relatively inconsequential for his career choice in the United States; however, we could speculate that if Bill had remained in his native Argentina, environmental influences would have been a much more heavily weighted consideration, since the probability of playing American style football was nil, regardless of his self-beliefs or career aspirations.

We can see from Gramática’s decision-making process that Bill’s motives were influenced by many different types of personal appraisals. Through deductive reasoning and reflective thinking, and using his brother as a behavioral model, Bill evaluated his past performance, current abilities, and future aspirations, making an informed decision that was guided by his overall beliefs about family and commitment. He made performance assessments based upon generalized impressions of his previously demonstrated athletic skills. He evaluated potential career options, comparing the relative degree of worth and importance to ancillary factors, such as pursuing higher education while playing college football. He considered the prospect of committing to a goal that his brother would expect him to achieve, and he contemplated the probabilities of when, where, and how to reach his desired outcome of personal, familial, and career satisfaction.

The perceptive motivational detective (MD) and the motivation scholar will likely detect elements of many theories of motivation intermingled with the previous analysis and entrenched within Gramática’s evaluative judgments and decision-making processes. Reflecting on past performances to make future decisions illustrates an attributional approach to motivation. Evaluating the potential rewards and liabilities of becoming a college place kicker demonstrates consideration of task values and expectancies. Contemplation of current abilities to predict future performance and probabilistic outcomes shows a cognitive evaluation of personal efficacy. However, by now the astute MD realizes that each approach to explain motivated behavior must be evaluated at different levels of detail, specificity, and temporality to be fully understood. It is prudent to understand not only what decisions are made but also the reasons behind the decision-making process.

When contemplating a performance or academic task, individuals undergo a series of evaluations and reflective judgments to determine task choice, while assessing the degree of effort and commitment they are willing to invest toward reaching their intended goals. Understanding the source of information for evaluative judgments is an important first step in predicting which behaviors will manifest as a result of a choice and which strategies the individual will use to progress toward his or her goals. Social cognitive theory suggests that evaluative decisions are based, in part, upon a variety of interdependent cognitive, affective, and contextual factors that collectively influence behavior; logic does not always prevail. The important and variable role of affect and emotional valence on task choice and devotion of effort should not be underemphasized and is discussed extensively in Chapter 9 (p. 237). Now, I turn to identifying and assessing the relative influence of cognitive factors used in determining personal agency.

Principle #36—Past performance guides future motivation

Visualize a recurrent task or challenge that you usually execute flawlessly. Maybe you excel at playing tennis, are a whiz at solving mental multiplication problems, or have a reputation for being the life of the party. The types of tasks you could select are infinite but essentially inconsequential. Regardless of the task or challenge, whenever you contemplate motivated action, you make both implicit and explicit cognitive judgments about how successful you might be at performing the task while likely visualizing the probable outcomes resulting from your task-based decision. In all likelihood, the task you consider and the one you eventually select will be motivated by the reasonable prospect of being able to do the task well. So, which task did you choose?

Scholars might contest the antecedents of your task-selection thought process. Some would contend that your choices and subsequent performances were based upon overall enjoyment and interest. Others might deduce that the visualization of a successful outcome was the main reason for your task choice, with the prospect of an impeccable performance strengthening your existing interest and influencing your choice. Regardless of what ignites task engagement, the potential for a positive outcome attracts individuals toward attempting and completing tasks, while the anticipation of negative results usually inhibits task desirability and accelerates task avoidance (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995; Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2005). Unless the task is something never previously attempted, more often than not, during task selection, you will make a series of evaluative cognitive judgments concerning the degree of challenge you are willing to accept, an appraisal of how you will complete the task, and a projection of potential task outcomes, including how completing the task will make you feel. Each task-relevant judgment involves a series of personal calibrations, resulting in the assumed alignment of your perceptions of task competence to the anticipated task demands. Ultimately, your task choice and associated engagement strategies are grounded in task-related personal beliefs, based, in part, on competence perceptions, which emanate from results on similar past performances.

Assessments of past performance as a barometer of future task choice and potential task engagement are based upon the core principles of attribution theory, which suggests that individuals seek justified explanations that guide future effort investments. Grounded in the seminal work of Rotter (1966) and popularized by Weiner (1979, 2012), attribution theory suggests that positive task consequences are insufficient to explain future task choice and engagement. Critical to attribution theory is an understanding of the powerful role of individual beliefs concerning perceived retrospective reasons for past success or failure, which are thought to be highly instrumental in determining future task orientation and motivated effort. In other words, individuals possess an inherent curiosity and evoke a deliberate conscious affinity toward knowing and understanding how accomplishments are attained as a means to assess, calibrate, and validate personal values and future intentions (Baumeister & Finkel, 2010).

Attributional musings remind me of a time when I contemplated the ludicrous notion that I could bake a carrot cake from scratch. Although not an “Iron Chef” by any account, I know the difference between a fork and chopsticks, and in spite of being a stereotypical male, I can follow recipe directions, even without pictures. I methodically added the ingredients as instructed, preheated the oven, and mixed the batter to a fine lumpy consistency. The result was a slightly fluffy concoction resembling a burnt pancake, charred on the outside, wet and sagging in the middle, and bearing a striking visual resemblance to rotting squash. Maybe I should not have used frozen carrots? But why did I really fail, or more realistically, why did I believe I failed at the baking task? Having heard a litany of student attributions for poor performance over the past 10 years, I was well equipped to rationalize the reasons for my own catastrophic cake. I quickly concluded that the recipe was far too complicated, the baking temperature of my oven was obviously miscalibrated, and my ingredients were apparently inferior. I attributed my failure to a variety of factors beyond my personal control that would likely remain unchanged, if I ever dared to bake again. In any event, who wants to waste time baking a cake when one can easily be purchased at a bakery for half the cost? I concluded that baking is reserved for others with greater culinary skills, which clearly excluded me.

Although my cake disaster was not an academic achievement (although I tacitly learned how NOT to bake a cake), the espoused rationale for my failure exemplified specific attributions, or self-assessed causes, as to why I failed. Attributions are best understood by examining three specific underlying dimensions related to interpreting task outcomes. First, assessment of causal locus provides evidence as to the source of responsibility for the achieved outcome. Individuals generally rationalize why they succeeded or failed, ascribing responsibility for outcomes based on either internal self-strivings, or like me, attributing outcomes to external causes unrelated to the self. In other words, I rejected the notion that my personal ability or effort was the reason for my failed cake. Instead, I concluded that a variety of contextual factors were responsible for the outcomes I achieved, including the recipe being too hard to follow, a defective oven, and the need for better ingredients, all factors unrelated to my personal skills or the degree of effort I had invested. Alternatively, I might have concluded that my failure was the result of internal deficiencies, including the apparent absence of the baking gene in my genetic code, poor planning, questionable ability, or lack of personal effort and attention devoted to the baking process.

In addition to having an internal or external antecedent, attributions are based on perceptions of personal ability or on the degree of effort invested in a task (Weiner, 1979). Ability attributions suggest the depth of skill and extent of talent determine task results. When an individual fails, ability attributions leave learners vulnerable to feelings of despair, lower self-esteem, and promote negative ruminations, as the individual, in many cases, may believe that deficient skills will limit future success on similar tasks. Subsequently, motivation to complete the task decreases. In contrast, effort attributions inspire more encouraging performance expectations, as the individual believes that there is a direct connection between the amount of effort invested in a task and the quality or efficiency of task results. When effort attributions prevail, the individual is likely to muster additional resources when presented with a similar opportunity, fostering feelings of optimism, hope, and potential pride, leading to robust adaptive motivation on similar subsequent tasks.

Assessments of stability or the perceptual permanence of attributions are an important second causal dimension of task-directed behavior. Weiner (2010) suggested that the perception of stability, or the predictability of outcomes, was as instrumental in performance domains as causal locus. Attributions are perceived by individuals either to persist over time, showing consistency between similar tasks, or to be unstable and malleable. Outcomes lacking perceived stability suggest that each occurrence or opportunity presents an additional chance for the individual to demonstrate competency and reassess the source of success or failure. Sadly, I believe my cake-making ability is immutable: I doubt that any cooking class would improve my baking skills, suggesting a highly stable ability-based attribution. It is extremely unlikely that I will ever raise a spatula again! In the vernacular of attribution theory, I exemplify learned helplessness, since I have been conditioned to expect baking failure. I am unwilling to devote additional effort to baking because I believe that any effort to improve my baking skill will be fruitless, especially if baking a carrot cake. When it comes to cake baking, I have surrendered psychologically because I am unwilling to expose myself to additional humiliation. From a motivational perspective, I have abdicated effort and responsibility for my task outcome because I believe there is minimal probability that anything will reverse my baking misfortunes.

Controllability is the third dimension influencing causal attributions. Controllability implies that the individual believes that they are able to orchestrate the nature and quality of performance outcomes. Most individuals actively strive to control the outcomes of the challenges they elect to pursue. If an individual believes he or she has influence over outcomes and then experiences success, the person will also believe that effort expenditures are warranted and worth the necessary cognitive investment. When the same individual encounters formidable obstacles or task failure, he or she may attribute performance decrements to lack of effort, such as when low grades are earned because of not studying enough for an important examination. Individuals who achieve success when harboring deficient control beliefs usually attribute positive outcomes to either a stroke of luck or to the apparent ease of the task. Questionable control beliefs are prone to decrease the effort invested in a task because the person sees little relation between effort and outcomes. An external causal locus and minimal controllability beliefs constitute a particularly lethal combination, usually resulting in attributions equivalent to believing in bad karma or a questionable horoscope, such as the feelings I experienced during my colossal cake caper.

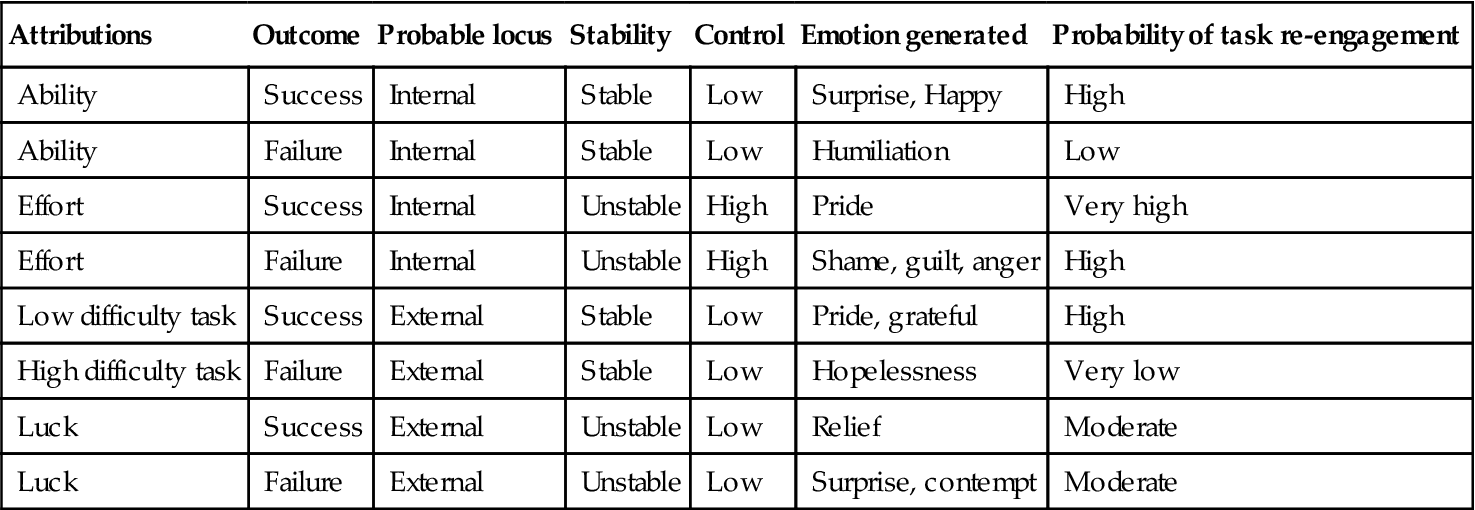

Most salient to the MD are the behavioral implications of various attributions and the expectation that certain attributions will likely result in a set of highly probable corresponding behaviors and emotions. When individuals expect success, they will enthusiastically pursue task goals, exerting cognitive energy in the optimistic anticipation of a positive result. Conversely, when negative outcomes are anticipated, lethargy, procrastination, or deliberate task avoidance is likely to follow (Atkinson, 1964). In turn, the behavior produces a corresponding set of emotions associated with success or failure. Negative expectations generate undesirable feelings and a corresponding decrease in task engagement, resulting in maladaptive motivation and reduced effort. Consequently, if the individual presumes a positive outcome, a corresponding positive affective valence will be associated with the task, and likelihood of sustained effort or task re-engagement will increase. Table 7.1 illustrates the relationship among perceived causality and the attributional and emotional consequences associated with each task orientation, as well as the likelihood of task re-engagement.

Table 7.1

Selective causal attributions and associated dimensional likelihoods

| Attributions | Outcome | Probable locus | Stability | Control | Emotion generated | Probability of task re-engagement |

| Ability | Success | Internal | Stable | Low | Surprise, Happy | High |

| Ability | Failure | Internal | Stable | Low | Humiliation | Low |

| Effort | Success | Internal | Unstable | High | Pride | Very high |

| Effort | Failure | Internal | Unstable | High | Shame, guilt, anger | High |

| Low difficulty task | Success | External | Stable | Low | Pride, grateful | High |

| High difficulty task | Failure | External | Stable | Low | Hopelessness | Very low |

| Luck | Success | External | Unstable | Low | Relief | Moderate |

| Luck | Failure | External | Unstable | Low | Surprise, contempt | Moderate |

Source: Based on Weiner (2012).

Weiner (2012) emphasized that causal cognitive ruminations generate feelings, but that attributions alone do not propel individuals to act in a certain way or point the individual in a specific affective direction. The emotional consequences of individual attributions do not evolve in social isolation but, instead, are socially influenced. Like many emotional triggers, the development, evolution, and display of emotion is frequently contextually bound and based upon self-referent comparison and anticipated reaction from others. Imagine the academically unsuccessful student or the forlorn co-worker explaining how their poor planning or procrastinating nature resulted in a pitiful test performance or project failure. If significant others determine that the poor performance was within the control of the individual, indifferent responses to the individual are almost guaranteed. Conversely, if a justifiable circumstance inhibited successful performance, sympathy and understanding would likely result.

Devoid of the need for justification, individuals are more prone to ascribing negative self-appraisals to external factors in order to avoid feelings of personal demoralization. Frequently, “self-serving” bias is observed, whereby success is often justified as internally derived, but task failure is attributed to external ascriptions (McClure et al., 2011). Although feelings of pride, shame, guilt and anger can be self-induced and based strictly upon self-impressions, quite often, individuals ascribe personal worth and expectations based upon societal, gender, and cultural norms. In school, a substantial portion of students’ attributional information is based upon teacher judgments and expectations (Dompnier, Pansu, & Bressoux, 2006; Sudkamp, Kaiser, & Moller, 2012). Similarly, in organizations, performance feedback to employees is strongly influenced by how supervisors assess worker attributions (Martinko, Douglas, & Harvey, 2006), with assessments influencing pay and compensation (Reb & Greguras, 2010).

Finally, the social nature of attributions is emphasized by examining cross-cultural and gender differences. Generally, studies conclude that individuals with a collectivist orientation (see Chapter 5, p. 118) ascribe causality for achievement to externally derived socially influenced sources, whereas people in individualist cultures have more intrinsic attributions, as well as the belief that their attained outcomes are more controllable (Zusho, Pintrich & Cortina, 2005). As for gender, stereotypical patterns are usually observed both within and between cultures, with females often attributing performance excellence to the exertion of greater effort, while subpar performances are attributed to poor ability, more so than their male counterparts (McClure et al., 2011). However, some attributional phenomena are constant, regardless of culture or gender. In a comprehensive meta-analysis, Mezulis, Abramson, Hyde, and Hankin (2004) substantiated the ubiquitous, self-serving bias that permeates all cultures, with individuals universally attributing success to more internal and stable causes, rather than taking deliberate and intentional personal responsibility for their own paltry performances.

One person with easily recognized internal, highly stable, and controllable effort attributions is former NFL superstar Nick Lowery. Seven times an “All Pro,” Nick was selected to the Pro-Bowl three times and was inducted into the Kansas City Chiefs Hall of Fame in 2009. At the time of his retirement, he was the most accurate and prolific field-goal kicker in NFL history. Nick set four all-time NFL records all after being cut 11 times by eight NFL teams! I asked Nick how he felt when 60,000 manic fans were screaming at him and he missed a potential game-winning field goal because of a wayward kick. Nick explained that taking personal responsibility for performance outcomes is inherent to anything he has ever attempted or done, including field-goal precision. He enthusiastically responded, “If I go through life thinking that I need things that are outside my locus of control (i.e., me), then I will always feel some kind of void that I don’t have what it takes. It comes down to realizing we control our destinies. Always, always, always, it is necessary to give ourselves the permission to learn. With that assumption then mistakes become part of the overall plan, rather than an exception.” Nick added, “All I can do is learn and to be sure I will never make the same mistake again. I was in a game in Buffalo when an 80-year old lady was hurling verbal and visual obscenities at me like an angry trucker. The wind was blowing at 20 mph, and the wind chill was five degrees below zero, but I knew I couldn’t control her or the weather, all I could do was learn. I was thinking, what would I do to ensure that this [failing] never happens again?” (N. Lowery, personal communication, January 2, 2014). Nick’s attributional approach to kicking field goals applies to most other aspects of his extraordinary career, suggesting that at least by his example, casual attributions and personal beliefs concerning past performance generalize to the future challenges a person is willing to consider.

Principle #37—Certain motives are extraordinarily difficult to suppress

In addition to qualitatively examining our past performances as a source of task-relevant information guiding future engagement decisions, individuals also make ongoing, real-time cost–benefit evaluations as to how they want to direct and invest their available cognitive resources. Originating in the formulaic “approach and avoid” models of Atkinson (1964) that sought to predict the probability of task engagement and popularized by the application of expectancy incentives to school achievement (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000), expectancy-value approaches suggest that when individuals contemplate task engagement, they make a series of culturally-nuanced weightings and assign personal priorities to different task aspects while concurrently ascribing relative value and worth to prospective task outcomes. Expectancy-value theory is frequently used to explain how idiosyncratic incentives are instrumental in achievement motivation; however, the approach is also used to answer broad and varied research questions across domains and cultures (Wigfield, Tonks, & Klauda, 2009). Some applied research questions that have been answered using an expectancy-value lens include: under what conditions do individuals demonstrate organizational trust (Viklund & Sjöberg, 2008), which factors undermine the willingness of individuals to exercise (Yli-Piipari & Kokkonen, 2014), and what type of information influences science career aspirations (Nagengast et al., 2011)?

Perhaps the best example of the practical utility of expectancy-value theory can be drawn from one of the supreme moments in movie history, evoking one of the most memorable and powerful lines of all time from The Godfather, when underworld boss Don Corleone (played by Best Actor winner Marlon Brando) said, “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.” Brando was alluding to his highly successful ability to persuade individuals to agree with his desires. In this instance, he convinced a recalcitrant Hollywood producer to cast his godson Johnny Fontaine (played by Al Martino), a fading star, in a leading movie role. The producer, who was originally adamant in his resistance to casting Johnny, finally realized the value and importance of changing his decision when he woke up in bed drenched in blood from the decapitated head of his prized racehorse, which was strategically placed under his blanket while he slept as an incentive to change his mind. While the factors we evaluate and the magnitude of the decisions we face are far less graphic and sensational, we regularly make judgments about the importance of task-relevant criteria and evaluate the physical and psychological incentives and consequences of task engagement.

Like other stalwarts on the motivational Mount Rushmore, the foundation of expectancy-value theory rests heavily on the role of personal competency beliefs and the presumptions individuals have about prospective task outcomes. When evaluating task choice through an expectancy-value lens, individuals first appraise the incentive value of a task, which is based upon four evaluation criteria: attainment value, intrinsic value, utility value, and cost (Eccles et al., 1983). Attainment value represents the degree of relative importance the individual places on the contemplated task. Intrinsic value is measured by how much an individual subjectively enjoys doing and completing the task. Utility value represents the degree of usefulness afforded to doing or mastering the task from an applied perspective; a task high in utility value would be valued or perceived as proximal and instrumental to achieving longer-term goals, such as taking a course to enhance one’s career development. Alternatively, utility value can be perceived as low, or even negative, if the task is deemed unnecessary to advance individual long-term goals. Cost represents the subjectively determined, personal, and/or psychological consequences associated with task engagement, including, but not limited to, the inability to perform other more desirable tasks, the degree of cognitive effort invested in the task, or the social stigmas associated with reaching perceived task outcomes.

Expectancy-value approaches are an effective means of examining the choices individuals make in both the classroom and a variety of other domains. Understanding how learners evaluate academic tasks can help predict what courses they will take and what assignments they will do (Simpkins, Davis-Kean, & Eccles, 2006) and may assist in determining when and if they will develop intrinsic motivation and interest for a particular task (Wigfield & Cambria, 2010). Value assessments can be highly stable and psychologically durable. In one longitudinal study, Durik, Vida, and Eccles (2006) found that subject judgments made in grammar school were so enduring that they accurately predicted the frequency of future literacy choices 6 years later. Outside of the classroom, expectancies are strong indicators of the willingness of individuals to engage in and perform a diverse set of behaviors, such as the degree of effective self-management employees demonstrate at work (Lord, Diefendorff, Schmidt, & Hall, 2010), when, if, and how online learners use wiki-tools to enhance collaboration (Ertmer et al., 2011), and even the intentionality and associated expectations for using a condom (Albarracín, Johnson, Fishbein & Muellerliele, 2001)!

The value and usefulness of expectancy approaches in applied settings requires careful consideration of how individuals make task-relevant judgments. Several interpretive threats challenge the over-reliance on expectancy-value conclusions as a means to explain motives. First, the valuation of expectancies and outcomes relies almost exclusively on individual self-report. The individualized nature of task assessment is both a strength and a weakness of the approach. Asking individuals to evaluate tasks provides an excellent opportunity to glimpse into the introspective nature of causal outcomes and examine the underlying beliefs that influence personal expectancy assessments. However, as described in Chapter 2, individuals are notorious for misinterpreting their own motives and frequently display personal bias, often evaluating task outcomes based upon perceptions of social desirability, including ascribing preferential normative values to certain more desirable tasks and careers. Wigfield, Cambria, and Eccles (2012) recommended using multiple measurements of task expectations and evaluating outcome expectancies after task completion as a means to counteract the liabilities of self-report and to solidify subsequent inferences.

Second, we should expect variation regarding which aspects of a task individuals consider when making evaluative judgments. Task demands may be ambiguous, and individuals may not accurately gauge what skills are needed to complete a specific task. Further, the investment of cognitive and motivational effort toward task completion is not a linear process. Vacillations of effort frequently occur, which can result in individuals re-evaluating both task values and outcomes during task engagement. Consider the individual who is optimistic at task start but loses confidence and becomes frustrated from lack of task progress as the task becomes increasingly challenging. Negative anticipatory ruminations may quickly emerge. Try putting together a do-it-yourself modular desk or a barbeque grill that requires you to follow convoluted instructions, and you will quickly relate to why and how success beliefs concerning task outcomes may quickly change. Additionally, individuals experience challenges with accurately calibrating effort assessments because those calculations are contextually and temporally bound and are, in part, determined by the influence of expertise (Beckmann, 2010). Individuals frequently miscalculate and misinterpret the degree of mental workload needed to complete a task, thus impeding accurate effort assessments and measurement (Hoffman, 2012).

Third, as with any task judgment, we should consider the stability of assessments, which can change radically over the course of time. Outcomes once highly valued can be frequently recalibrated, resulting in a wide disparity both between and within individuals. In addition, individuals are subject to faulty assessments, especially when ascribing value to a certain outcome (Bandura, 1997). By example, an individual can pursue a college degree for a number of potential reasons, including financial reward, knowledge acquisition, preferential social status, or merely for personal accomplishment. If offered a high-paying job before degree completion, the once highly prized degree can become instantly superfluous, plummeting in perceived value and reducing task engagement. Degree continuance would be subject to the original motive source and the fluctuating perceived value of the diploma, regardless of payoff.

Fourth, task valuations are partly influenced by social dynamics. Sociocultural factors may result in a task being embraced in one context and yet blatantly devalued in another. Attainment value and utility value are not absolute, as a skill deemed desirable in one social setting may be unimportant or even stigmatized in a different context of application. For instance, in some businesses, attitudes toward advanced education, and PhDs in particular, may be negative (Fendt, 2013). The identical credentials can be revered in other venues, such as academics, where a terminal degree is usually an employment prerequisite (Karl & Peluchette, 2013). Therefore, close examination of prevailing social norms is essential when evaluating expectancy motives. Coincidentally, back in 1972, when Marlon Brando won the Best Actor award, in a socially historical moment, he elected to repudiate the award in protest of the treatment of Native Americans in film and television. Apparently, Brando’s ascribed value to the honor was inconsistent with the valuation of his peers, who were astonished that he would reject such a coveted honor.

Finally, examination of a compendium of evidence reveals that the variability associated with task outcomes can be more reliably predicted by other self-reflective judgments beyond expectancy considerations. The degree of confidence that individuals ascribe to achieving certain courses of action or outcomes may provide superior explanatory power in understanding motives than expectancies alone. Bandura (1997) indicated that “when variations in efficacy beliefs are controlled statistically, the outcomes expected for a given performance contribute little to the prediction of behavior” (p. 126). Bandura contended that outcome judgments made during the evaluation of expectancies do not account for many causal beliefs that influence performance, including inattention to the deliberate or unintentional self-handicapping strategies individuals employ that may impede goal progress (see Chapter 8, p. 225). Outcome expectations are especially vulnerable in situations where an individual must demonstrate adaptivity and creativity to meet ill-defined task demands, as task demands are far less clear or predictable during exploratory learning. In sum, according to Bandura (1997), the inclusion of self-efficacy when making evaluative judgments of task outcomes provides better support for explaining variations in motivation than merely accounting for task incentives and outcome expectancies. Thus, we next turn to another celebrated cornerstone of the motivational Mount Rushmore and explore the powerful influence of self-efficacy evaluations as a conduit for successful learning and performance.

Principle #38—After ability, self-efficacy explains more performance variation than any other motivational self-belief

When examining the similarities among our motivational leaders, at least one common theme prevails. Each personality articulated a deeply entrenched belief indicating willingness to do whatever it took to attain a desired goal or reach an anticipated outcome. Nick Holes lives by the maxim inscribed on his toes “Keep moving.” Darren Soto (see Chapter 10, p. 288) affirmed “I work at things that I know I can attain.” Alec Torelli alluded to how he competes against his own inner voice stating, “I focus on the things that I can control and get done” (A. Torelli, personal communication, May 13, 2014). Cheryl Hines pronounced, “Brace yourself for the worst, but the worst doesn’t usually happen. Just push yourself until you get what you want” (C. Hines, personal communication, May 22, 2014). Ironically, Cheryl was describing how she was rejected three times when auditioning for the same role on the television series “Swamp Thing.” On her fourth try, Cheryl finally earned the part and launched her illustrious career, attributing her success to drive and ambition, and demonstrating an emphatic self-belief that she ultimately expected to succeed.

The leaders described a unique blend of distinctive talent and exceptional abilities that contributed to their successes. Conceptions of performance across domains reveal that what we already know, as well as our own performance history, explains about 30% of the variability in future performance outcomes (Sitzmann & Yeo, 2013). In other words, prior experience does contribute to future success. However, 70% of the variability in future performance outcomes is explained by factors other than what we already know or what we have previously accomplished. We might then surmise that the success of our motivational leaders is attributed to their inclination to persevere in the face of obstacles, their lofty aspirations, blind optimism, good looks, or perhaps the perception of being in control of their own destinies. These potential explanations for superior performance are warranted, to some degree, by empirical evidence, but clearly, in aggregate, the most probable explanation for successful performance outcomes, after accounting for existing skills and experience, is domain-specific self-efficacy. The belief in one’s capability is a powerful force that assists the individual in organizing and executing courses of action that produce desired results (Bandura, 1997).

According to over 40 years of programmatic research conducted across domains and cultures, after controlling for fundamental ability distinctions, no other variable has greater mediational power over performance outcomes than self-efficacy beliefs. The pervasive and positive influence of self-efficacy on performance is demonstrated in academics (Pajares, 1996), in organizations (Wood & Bandura, 1989), during work performance (Stajkovic, & Luthans, 1998), and in athletic competition (Moritz, Feltz, Fahrbach, & Mack, 2000) and is a catalyst for overall physical activity (Plotnikoff, Costigan, Karunamuni, & Lubans, 2013). Self-efficacy beliefs are not based on a quantitative or qualitative assessment of a repertoire of demonstrated experience or skills. Instead, self-efficacy beliefs are motivational antecedents, consisting of cognitive and affective self-assessments that prime the individual for focused action, based upon what we believe we can accomplish. The strength of beliefs concerning ability perceptions is instrumental in superior performance because the individual believes that he or she has the cognitive horsepower, executable skills, and tangible strategies to produce desired outcomes for a specific task. Armed with a foundation of knowledge and experience, individuals possessing elevated self-efficacy beliefs will consistently outperform their lower self-efficacy peers in domains as varied as writing (Bruning, Dempsey, Kauffman, McKim, & Zumbrunn, 2013), playing musical instruments (McPherson, 2006), using Internet technology to promote learning (Lee & Tsai, 2010), and making assessments unrelated to specific performance metrics, such as seeking sensual pleasure, and anticipatory emotions, such as happiness and hope (Maddux, 2002).

The power of self-efficacy to mediate performance is based, to some extent, on positive associations among elevated self-efficacy levels and key indicators related to learning and performance. The belief in one’s abilities exerts both direct influence and incidental influence on outcome perceptions. For instance, as the degree of self-efficacy increases, learners will deliberately elect more formidable classroom challenges when weighing academic goals and contemplating classroom activities (Zimmerman, Bandura & Martinez-Pons, 1992; Zimmerman & Cleary, 2009). Enhanced self-efficacy is related to academic persistence (Wright, Jenkins-Guarnieri, & Murdock, 2013) and resilience when under stress (Benight & Cieslak, 2011) and has strategy implications, as highly efficacious learners are more efficient problem solvers (Hoffman & Schraw, 2009). From an applied perspective, the influence of self-efficacy is broad and ubiquitous. Self-efficacy levels foretell which subjects’ learners are willing to study and the career choices they will eventually make (Betz & Hackett, 1983). The degree of self-efficacy also serves as a reliable lifestyle predictor, indicating what types of strategies individuals will or will not use to manage their health and health issues (Plotnikoff, Lippke, Courneya, Birkett, & Sigal, 2008).

Elevated levels of self-efficacy exert indirect positive influences on a variety of performance outcomes and are instrumental in directing individual and collective effort investments. Most notably, enhanced levels of self-efficacy contribute to learners using a broader repertoire of academically productive learning strategies, such as enhanced mental monitoring of accuracy and metacognitive awareness. High self-efficacy learners generally show adaptive motivation during learning by processing information more deeply than their lower-efficacy peers (Wood & Bandura, 1989). Self-efficacy also makes independent contributions to the emotional experiences individuals report when completing tasks (Bandura, 2012), including reducing stress perceptions and moderating anxiety reactions. As self-efficacy levels increase, emotional stability is elevated, while perceived neuroticism decreases (Judge, Jackson, Shaw, Scott, & Rich 2007).

When measured at the group level, collective efficacy reveals interdependent linkages among team members, influencing systemic organizational performances. Like individuals, groups and teams with elevated efficacy levels are typically associated with superior performance outcomes. The profound benefits of collective efficacy are particularly useful to predict teaching effectiveness and achievement gains at the school or district level (Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2004), to positively influence employee job satisfaction (Borgogni, Dello Russo, & Latham, 2011), and to enhance overall organizational and group dynamics (Prussia & Kinicki, 1996; Stajkovic, Lee, & Nyberg, 2009) in both corporate (Murphy, Cooke, & Lopez, 2013) and competitive athletic domains (Chow & Feltz, 2007).

Operating under the presumption that instilling elevated levels of efficacy in the self and others is highly advantageous for learning and performance, the next logical step for the aspiring MD is discovering the sources and useful strategies necessary to cultivate self-efficacy beliefs. The development and accrual of adaptive self-efficacy beliefs starts with providing individuals with opportunities to receive task-relevant feedback that is credible, positive, and integrated within the self. Termed “enactive mastery experiences” by Bandura (1997, p. 80), any exceptional performance outcome that is intentional and perceived to be within the control of the individual will potentially enhance self-efficacy. Mastery requires supportive contextual conditions that provide appropriate structure and guidelines to allow the individual to harness and apply ambitions, skills, and strategies to reach premeditated goals. When the individual surpasses desired performance thresholds and equates success with personal agency, self-efficacy is enhanced. Critical to fostering increases in self-efficacy are mastery experiences that are commensurate with existing talents and ability. Individuals overwhelmed by task demands or those able to meet task goals without cognitive exertion or minimal effort will either see efficacy levels remain stable or decrease. Contemplated tasks must be both attainable and challenging; otherwise self-efficacy will be foiled due to overwhelming complexity and cognitive load or because of minimal cognitive stretch that is insufficient to foster intellectual growth.

To a lesser extent, self-efficacy levels can be enhanced by the actions of others if the other is deemed capable and significant. Bandura (1997) suggested that vicarious experience enhances self-efficacy when one’s own performance is mediated by observing the skills of a competent model. When individuals have the opportunity to witness other highly regarded individuals performing contemplative tasks, efficacy beliefs elevate because social comparison aids the individual in visualizing successful personal task completion and feeling confident that the observed performance can be replicated. Grounded in behavioral learning theories, if the physical and emotional consequences of performing a task are perceived as positive, emulation is encouraged. Likewise, if outcomes are perceived as undesirable or are associated with the perception of unwelcomed emotional consequences, a negative model can be psychologically debilitating and adversely impact self-efficacy and an individual’s motive to replicate a task.

Verbal encouragement in the form of constructive feedback received from credible others may also enhance self-efficacy. When an individual receives verbal affirmation (Bandura, 1997) originating from a reliable source, the feedback is integrated into his or her personal belief system. The encouragement from others is based on personal faith and designed to reassure the dubious learner of his or her prospective abilities. As the learner integrates the encouragement into individual self-perceptions, efficacy beliefs escalate. An excellent example of the power of verbal persuasion was described by Rebecca Hines, who responded to the repeated laments of frustration from her then-struggling sister Cheryl. When repeatedly discouraged by failed auditions, which stalled her acting career, Cheryl developed personal skepticism concerning her acting ability. Rebecca advised Cheryl that rejection was inherent to the acting profession and that experiencing failure was necessary to achieve success. Although Rebecca had no acting experience, she communicated her faith in Cheryl’s abilities even in the face of repeated rejections, which resulted in modifying Cheryl’s self-doubts. Cheryl integrated her sister’s verbal encouragement into her self-view, becoming more accepting of potential failure but without letting this acceptance impede her motivation to succeed despite the repeated obstacles encountered. One would be remiss in believing that simple encouragement or vicarious performance is sufficient to transform self-efficacy beliefs. Fundamental skill is a necessary prerequisite to maximize belief change, even for the most optimistic individual. Devoid of sufficient skill, the doubting learner would, indeed, be condemned to failure, regardless of the persuasive abilities of a competent mentor or the extent of positive self-beliefs.

Finally, physiological and emotional predispositions can be a catalyst of motivated action and be conducive to modification of existing self-efficacy beliefs. Performance outcomes and corresponding expectations during situations of high stress or anxiety can have either productive or potentially dangerous cognitive consequences. Anyone apprehensive about giving a speech or experiencing stage fright will likely relate to the debilitating effects of cognitive ruminations related to visualizing potential failure. Even the most practiced and integrated skills can be hampered during situations of heightened anxiety. Efficacy beliefs are particularly vulnerable when anticipating negative performance expectations.

Alternatively, heightened arousal can be a catalyst for positive anticipatory performances (Nicholls, Polman, & Levy, 2010). This phenomenon is observable during athletic performances, when athletes are provided the opportunity to display skills and abilities during high-pressure situations, such as during elimination or playoff games. The heightened sense of arousal stimulates physiological and psychological readiness in the individual. Optimal levels of arousal vary among individuals and are subject to vacillation based upon contextual conditions that influence the nature of the performance and subsequent self-efficacy perceptions. As an example, team performance is traditionally superior when teams have the home field advantage, more so than when competing in the opposition’s venue (Courneya & Carron, 1992). Optimal efficacy-building environments for one person can be quite unproductive for another, suggesting substantial variability among individuals based upon subjective interpretations of somatic events (Bandura, 1997).

Maximizing the predictive and diagnostic power of self-efficacy requires consideration of at least three critical analytical factors. First, self-efficacy beliefs are domain-specific beliefs and should not be measured at the omnibus level. Generalized beliefs differ from domain-specific self-efficacy beliefs, as the latter are based upon the appraisal of specific task-relevant criteria and the perception of specific skills and abilities individuals envision as being necessary to meet performance goals. Generalized measures, such as academic self-concept (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003), are less accurate in predicting performance outcomes in comparison with self-efficacy, which is most accurately evaluated at the task level (Judge & Bono, 2001).

Second, self-reported beliefs are subjective and can be misinterpreted. Individuals are vulnerable to errors of miscalibration, potentially over- or underestimating the degree of skills, ability, and effort needed to reach successful task outcomes. The accuracy of one’s own self-efficacy beliefs can be further impeded by misconstrued task demands that are malleable, temporal, and unstable based upon a variety of individual difference variables. The evaluation of task complexity is contingent upon level of expertise, availability of depletable cognitive resources expended during task completion, and conscious control of emotions experienced during incremental task success or failure.

Third, individuals make plausible assessments of prospective ability, which, in turn, should produce commensurate results. Ability assessments can originate from three sources: normative comparisons (i.e., other people), comparison with criterion thresholds indicative of specific content mastery, or comparison with one’s own past performances. Contingent upon the conceptual anchors used by an individual to calibrate self-efficacy beliefs, a broad spectrum of variability may develop in self-efficacy assessments. Individuals lacking sufficient experience or understanding of criterion standards may default to more identifiable socially-referent performance anchors. The nature of social comparison alone can forestall accurate calibrations of assessments. Individuals may fixate on or over-emphasize the affective consequences of performance competition, wanting to best a rival’s accomplishments, or align personal performance with that of a favored other, rather than making more reliable self-efficacy judgments on qualitative performance standards necessary to accurately and effectively complete a task.

The panacea of self-efficacy findings should be tempered and approached with caution. Self-efficacy, like many other motivational mediators, is interdependent, with accurate interpretations relying upon the influence of a variety of other individual difference and contextual variables, precluding an absolute or invariant positive affect on behavior (Bandura, 2012). In situations of task or effort miscalibration, self-efficacy may appear to inhibit effort or lead to increased errors (Vancouver, Thompson, Tischner, & Putka, 2002). Logically, overconfident learners may approach tasks with a lackadaisical attitude, deficient mindfulness, or speculating the ease of task completion. However, this calibration gap is not a reflection of the negative or null effects of self-efficacy beliefs but, instead, is predicated upon inaccurate and erroneous self-assessments. Bandura (2012) vehemently and eloquently contests the impotency of self-efficacy beliefs as pervasive and powerful due to methodological compromise and theoretical attenuation of disconfirming research. For MDs, cultivating self-efficacy should be a primarily goal, accomplished by leveraging the multiple sources and number of strategies previously outlined. Summarily, we can conclude that after controlling for performance enhancing influences, such as prior knowledge and experience, higher levels of domain-specific self-efficacy routinely predict beneficial performance outcomes—outcomes that are highly improbable for lower-efficacious peers (Bandura, 2012; Bouffard-Bouchard, 1990).

Principle #39—Motivational theory is applied temporally and situationally

An epigram used by Kurt Lewin (1951) to disseminate his views on social psychology is paraphrased as “There is nothing so practical as a good theory.” When evaluating motivation and performance phenomena in applied settings, practicality means that the premises of a theory provide broad explanatory power to understand behaviors, beyond those described during experimental simulations. Each theory discussed in this chapter meets the applied criterion based upon classroom and organizational applicability. A “good” theory is the metaphorical equivalent of grasping the ideal tool from a vast repertoire of options in the carpenter’s grandiose toolbox and using the tool properly to make needed repairs. Tools, however, can be rendered useless or harmful if used for purposes that are inappropriate or unintended. I have several scars as evidence of using pliers as a hammer to refute my creative tool theory. Ideally, one specific tool is considered optimal to complete a particular carpentry task. Similarly, the enduring theories of attributions, expectancies, and self-efficacy are best employed as situation- or task-contingent explanations of motivated behavior.

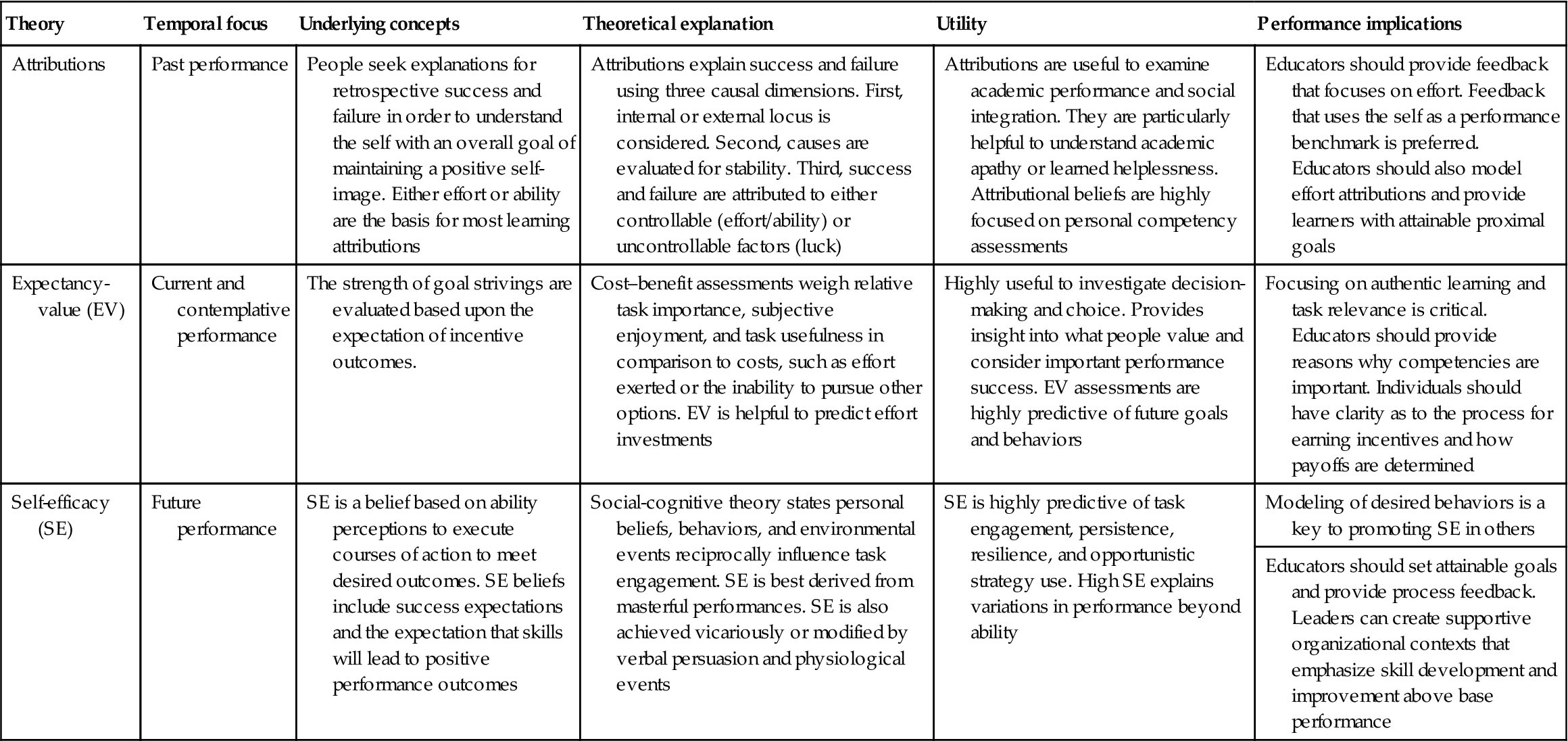

Although each theory is a viable explanation of agentic behavior, the construct emphasis of each view is conceptually different, suggesting that one approach may be more useful or appropriate than another to understand a particular motivational challenge. Relying too heavily on one interpretation of behavior may result in the all too frequent problem of confirmation bias whereby individuals exhibit an affinity toward identifying problems or seeking solutions that support their pre-existing notions while implicitly suppressing other plausible explanations of behavior (Greenwald, 2012). Avoiding theoretical bias means that tool selection for the aspiring MD involves a conscious realization that each approach to explain motivated behavior must be evaluated at different levels of detail, specificity, and temporality to be used effectively. Some people may dwell on past performances, while others will focus attention and effort on their current task challenges or demonstrate a focus on future performance goals. Popular diagnostic instruments, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, were specifically designed and validated to determine, in part, the degree of past, present, and future orientation of individuals as a means to enhancing personal growth and development (Cohen, Cohen, & Cross, 1981). Additionally, diagnostic approaches should be evaluated through a utility lens to answer specific research questions, with the understanding that one approach may be more relevant at a particular time than another. Table 7.2 outlines the main premises, temporality, and utility of each theoretical lens examined in the current chapter, including some suggested application strategies.

Table 7.2

Summary, utility, application, and comparison of chapter constructs

| Theory | Temporal focus | Underlying concepts | Theoretical explanation | Utility | Performance implications |

| Attributions | Past performance | People seek explanations for retrospective success and failure in order to understand the self with an overall goal of maintaining a positive self-image. Either effort or ability are the basis for most learning attributions | Attributions explain success and failure using three causal dimensions. First, internal or external locus is considered. Second, causes are evaluated for stability. Third, success and failure are attributed to either controllable (effort/ability) or uncontrollable factors (luck) | Attributions are useful to examine academic performance and social integration. They are particularly helpful to understand academic apathy or learned helplessness. Attributional beliefs are highly focused on personal competency assessments | Educators should provide feedback that focuses on effort. Feedback that uses the self as a performance benchmark is preferred. Educators should also model effort attributions and provide learners with attainable proximal goals |

| Expectancy-value (EV) | Current and contemplative performance | The strength of goal strivings are evaluated based upon the expectation of incentive outcomes. | Cost–benefit assessments weigh relative task importance, subjective enjoyment, and task usefulness in comparison to costs, such as effort exerted or the inability to pursue other options. EV is helpful to predict effort investments | Highly useful to investigate decision-making and choice. Provides insight into what people value and consider important performance success. EV assessments are highly predictive of future goals and behaviors | Focusing on authentic learning and task relevance is critical. Educators should provide reasons why competencies are important. Individuals should have clarity as to the process for earning incentives and how payoffs are determined |

| Self-efficacy (SE) | Future performance | SE is a belief based on ability perceptions to execute courses of action to meet desired outcomes. SE beliefs include success expectations and the expectation that skills will lead to positive performance outcomes | Social-cognitive theory states personal beliefs, behaviors, and environmental events reciprocally influence task engagement. SE is best derived from masterful performances. SE is also achieved vicariously or modified by verbal persuasion and physiological events | SE is highly predictive of task engagement, persistence, resilience, and opportunistic strategy use. High SE explains variations in performance beyond ability | Modeling of desired behaviors is a key to promoting SE in others |

| Educators should set attainable goals and provide process feedback. Leaders can create supportive organizational contexts that emphasize skill development and improvement above base performance |

Precise determination concerning which interpretive lens is most appropriate to mediate any particular motivational challenge should also include consideration of contextual and individual difference variables that influence task-directed behaviors. Contextual factors include social influences, such as the presence of particular individuals, in-groups, and organizational and cyber cultures that may alter behavior across contexts. Individual difference variables include special consideration of the specific aspects of a task individuals assess, including the realistic probability that people will overestimate abilities or erroneously appraise task requirements. Further, the adaptation of any particular theoretical model should consider how task appraisals change over time, including the evaluation of escalating expertise as learners gain more task experience. Finally, it behooves the MD to identify the source of self-referent evaluations. As will be described in Chapter 8, individuals make task evaluations from a variety of perspectives. Some will focus on their own past performance, others will identify certain skills they intend to master, and many others will approach a task with the hope of bettering their own past performance. The individual’s perspective may radically alter the suitability and analytical effectiveness of any one remedy, especially when individuals shift task-directed focus between normative and criterion performance standards.

Chapter summary/conclusions

Three prominent explanations of performance motivation were described in the current chapter: attributions, expectancies, and self-efficacy. Each explanation affirmed that our thoughts, emotions, and agentic behaviors are influenced, in part, by personal beliefs and values, the context of task implementation, and a variety of social influences, including the physical or psychological presence of others. The reciprocal nature of social cognitive theory suggests that task engagement is based upon the complex interplay of named influences, combined with personal evaluative judgments that determine subjective priorities, which result in differential weightings, ultimately determining what influence dominates any given task motivation. Individuals strive to find explanations for their performance results, as evidence for performance causality is instrumental in the development of self-identity. Most task engagement decisions are strongly influenced by competency beliefs, including micro-level appraisals of particular task-relevant skills and a belief in the ability to use those skills to attain desired performance outcomes. The source of competency appraisals is varied; some are based upon past performance, while others focus on current challenges or on the anticipation of gaining desirable future task outcomes.

Attribution theory uses a retrospective approach to determine the origins of academic success or failure, focusing primarily upon whether the individual believes her ability or effort is instrumental in achieving performance outcomes. The dimensions of locus, stability, and controllability contribute to evaluations of causality as individuals justify outcomes as either a product of their own agency or incongruous with their behavioral or motivational intentions. Expectancy-value approaches are based upon cost–benefit algorithms that assess relative perceptions regarding the degree of task enjoyment, interest, and usefulness individuals ascribe to the process of reaching task goals, while concurrently calculating the physical and psychological liabilities associated with reaching desired outcomes. Self-efficacy affects motivation by providing the individual with a set of entrenched, domain-specific evaluative beliefs that calibrate the adequacy of skills to complete a task. Self-efficacy beliefs also reveal the extent of control and regulation individuals believe they possess to successfully navigate contextual events that may impede the ability to orchestrate desired outcomes.

The interpretative lenses described are not ranked, nor is one preferential to another. Adapting a specific theoretical lens is based upon the judicious evaluation of a myriad of social cognitive factors and best determined by examining the overall patterns of behaviors exhibited by individuals. The self-beliefs described rarely develop from isolated events and, like all other self-beliefs, are influenced by cultural factors and developmental trajectories described in earlier chapters. Despite situational applicability, the masters of the motivational Mount Rushmore are highly effective in understanding academic and performance motivation, and the associated strategies should be well-worn tools in the MD’s toolbox.

Next steps

Operating under the premise that individuals universally desire positive self-images, it is not surprising that an important motive for many individuals is actively developing and seeking ways to maintain positive self-impressions. A positive self-image can be achieved in many ways; however, sometimes the behaviors individuals display in their self-affirming quest are not always representative of their precise motives and can be misconstrued by the casual observer. In addition, individuals may intentionally exhibit behaviors that lead to false impressions by others concerning underlying motives in order to preserve positive self-views. Chapter 8 examines several personal motivations and strategies primarily used to achieve the goal of elevated self-worth. Chapter 8 also introduces the reader to country music star Jessi Colter who has found that much of her self-esteem and happiness were derived from helping others achieve success and well-being, sometimes at her own expense.

End of chapter motivational minute

Principles covered in this chapter:

36. Past performance guides future motivation—reasons concerning the perceived causes of success or failures are instrumental in guiding future performance. Attributional dimensions, including causal locus, stability, and controllability, are useful measures to predict if an individual will engage with a task.

37. Certain motives are extraordinarily difficult to suppress—when contemplating task involvement, individuals make ongoing cost–benefit assessments to determine if a task has sufficient merit to justify engagement. Individuals consider task importance, enjoyment, value, and utility as a means of calibrating the materialistic and psychological payoffs associated with task completion.

38. After ability, self-efficacy explains more performance variation than any other motivational self-belief—the belief in one’s ability to attain desired outcomes is powerful. Elevated self-efficacy beliefs are related to greater persistence, resilience, and setting more challenging learning and performance goals. Most importantly, after controlling for ability, self-efficacy is a reliable predictor of performance.

39. Motivational theory is applied temporally and situationally—one explanation of motivation does not mediate all issues of learning and performance. The choice of mediational strategies is based upon individual differences and contextual factors in conjunction with an understanding of overall patterns of behavior.

Key terminology (in order of chapter presentation):

Reciprocal determinism—the interdependent network of personal beliefs and values, behaviors, and environmental factors that influence agentic action according to social cognitive motivational perspectives.

Reciprocal determinism—the interdependent network of personal beliefs and values, behaviors, and environmental factors that influence agentic action according to social cognitive motivational perspectives.

Causal locus—when ascribing attributional sources of success or failure, individuals consider factors internal or external to the self. An external locus suggests that individuals perceive environmental factors or chance as accountable for outcomes, while an internal locus indicates the individual believes ability or effort are the reason for task outcomes.

Causal locus—when ascribing attributional sources of success or failure, individuals consider factors internal or external to the self. An external locus suggests that individuals perceive environmental factors or chance as accountable for outcomes, while an internal locus indicates the individual believes ability or effort are the reason for task outcomes.

Ability attributions—internally focused causal beliefs associated with task success or failure, grounded in self-assessed perceptions of talent, skills, and ability.

Ability attributions—internally focused causal beliefs associated with task success or failure, grounded in self-assessed perceptions of talent, skills, and ability.

Effort attributions—internally focused causal beliefs associated with task success or failure, grounded in self-assessed perceptions of engaged effort devoted to a task.

Effort attributions—internally focused causal beliefs associated with task success or failure, grounded in self-assessed perceptions of engaged effort devoted to a task.

Collective efficacy—self-efficacy can be measured at individual or collective group levels. Elevated collective efficacy is related to enhanced team and group cohesion and frequently associated with highly-functioning team performance.

Collective efficacy—self-efficacy can be measured at individual or collective group levels. Elevated collective efficacy is related to enhanced team and group cohesion and frequently associated with highly-functioning team performance.

Confirmation bias—the subjective bias of individuals who seek out confirming evidence for their own theoretical view or opinion, while concurrently avoiding or ignoring falsifying evidence.

Confirmation bias—the subjective bias of individuals who seek out confirming evidence for their own theoretical view or opinion, while concurrently avoiding or ignoring falsifying evidence.

There is so much more to the Nick Lowery story than just football. Nick transcends any simple category. He is a Kansas City Hall of Fame athlete, Ivy-League scholar, a former presidential aide, poet, teacher, motivational speaker, and philanthropist. Nick’s life is about persistence, focus, and passion, regardless of where he dedicates his energy.

There is so much more to the Nick Lowery story than just football. Nick transcends any simple category. He is a Kansas City Hall of Fame athlete, Ivy-League scholar, a former presidential aide, poet, teacher, motivational speaker, and philanthropist. Nick’s life is about persistence, focus, and passion, regardless of where he dedicates his energy.