CHAPTER 37

Valproate

Charles L. Bowden, M.D.

History and Discovery

Valproate was the first mood stabilizer to be studied as an alternative to lithium (Lambert et al. 1966). An enteric-coated formulation, divalproex sodium, was approved in the United States for the treatment of mania in 1995. An extended-release (ER) formulation of divalproex was approved for migraine in 2001 and for mania in 2006. Valproate, either as divalproex or as other formulations, is now approved worldwide for the treatment of mania.

Pharmacological Profile

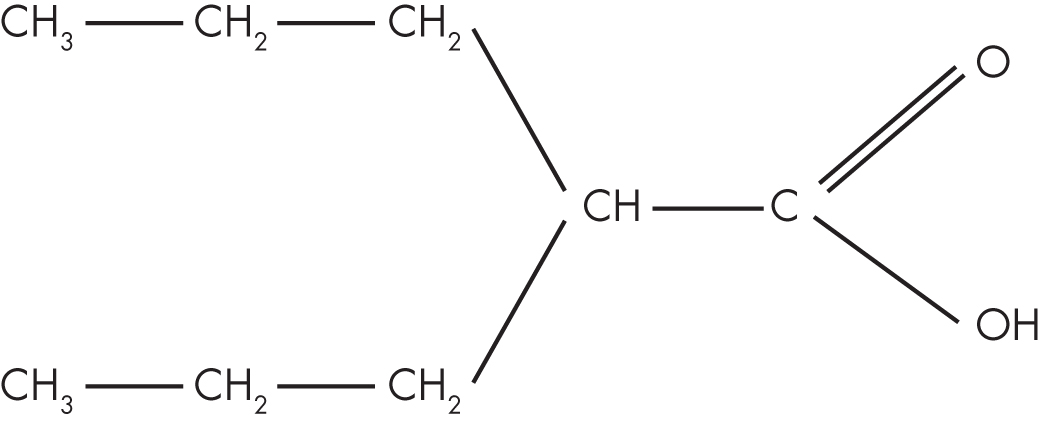

Valproic acid (dipropylacetic acid; Figure 37–1) is an eight-carbon, branched-chain carboxylic acid that is structurally distinct from other antiepileptic and psychotropic compounds (Bocci and Beretta 1976; Levy 1984). Its three-dimensional structure overlays that of naturally occurring fatty acids (e.g., oleic and linolenic acids). Valproate binds in a saturable manner to the neuronal membrane sites to which these longer-chain fatty acids attach. Some of valproate’s molecular mechanisms are likely a consequence of this physiochemical property.

FIGURE 37–1. Chemical structure of valproic acid.

Pharmacokinetics and Disposition

Valproate is commercially available in the United States in five oral preparations: 1) divalproex sodium, an enteric-coated, stable-coordination compound containing equal proportions of valproic acid and sodium valproate in a 1:1 molar ratio; 2) valproic acid; 3) sodium valproate; 4) divalproex sodium sprinkle capsule (containing coated particles of divalproex sodium), which can be ingested intact or pulled apart and contents sprinkled on food; and 5) an extended-release form of divalproex that provides once-daily dosing and a substantially flatter peak-to-trough ratio. Sodium valproate is available for intravenous use and, as such, has been demonstrated to provide reduction in manic symptoms within 1 day or less (Grunze et al. 1999). Valproate can also be compounded in suppository form for rectal administration. The valproate ion is the common compound in plasma.

The bioavailability of valproate approaches 100% with all preparations (Wilder 1992). With the exception of divalproex sodium, all preparations taken orally are rapidly absorbed. Sodium valproate and valproic acid attain peak serum concentrations within 2 hours. Divalproex sodium reaches peak serum concentrations within 3–8 hours. The ER form of divalproex sodium has an earlier onset of absorption than the regular-release tablets and approximately a 20% smaller difference in trough and peak serum levels than regular-release divalproex (Figure 37–2).

FIGURE 37–2. Mean plasma valproate concentrations with different formulations.

DR=delayed-release; ER=extended-release.

aData derived from different studies after 500-mg doses.

Source. Abbott Laboratories, data on file.

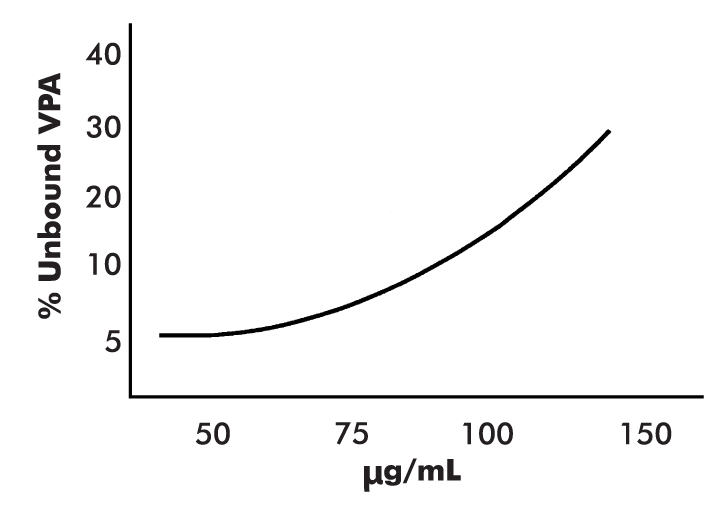

Valproate is highly protein bound, predominantly to serum albumin and proportional to the albumin concentration. Although patients with low levels of albumin have a higher fraction of unbound drug, the steady-state level of total drug is not altered. Only the unbound drug crosses the blood–brain barrier and is bioactive. Thus, when valproate is displaced from protein-binding sites through drug interactions, the total drug concentration may not change; however, the pharmacologically active unbound drug does increase and may produce signs and symptoms of toxicity. Moreover, when the plasma concentration of valproate rises in response to dosage increases, the amount of unbound (active) valproate increases disproportionately and is metabolized, with an apparent increase in clearance of total drug, yielding lower-than-expected total plasma concentrations (Levy 1984; Wilder 1992) (Figure 37–3). In addition, protein binding of valproate is increased by low-fat diets and decreased by high-fat diets. Because of lower serum protein levels, women and elderly patients will generally have a higher proportion of the active free moiety.

FIGURE 37–3. Total valproate (VPA) concentrations in the presence of.

As the total concentration of VPA increases, protein-binding sites become saturated, and the percentage of unbound to bound VPA increases.

Source. Reprinted from Wilder BJ: “Pharmacokinetics of Valproate and Carbamazepine.” Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 12 (1, suppl):64S–68S, 1992. Copyright © 1992, Williams & Wilkins. Used with permission.

The concentration range required for good clinical effect in mania is approximately 45–125 μg/mL (Bowden et al. 1996). Patients who are able to tolerate higher serum levels—up to around 125 μg/mL—may experience greater improvement (Allen et al. 2006). An open report suggested that individuals with rapid cycling in the context of bipolar II disorder or cyclothymic disorder may respond to serum valproate concentrations of less than 50 μg/mL (Jacobsen 1993). In maintenance treatment, patients whose serum valproate levels were maintained between 75 and 99 μg/mL had superior outcomes compared with patients whose serum levels were either lower or higher than this range (Keck et al. 2005). Valproate is metabolized in the liver, primarily through glucuronidation.

When used for the treatment of bipolar disorder, valproate is usually begun at a dosage of 15–20 mg/kg/day. The drug can be “orally loaded” at 20–30 mg/kg/day in patients with acute mania to induce a more rapid response. The dosage of valproate is increased according to the patient’s response and tolerance of side effects, usually by 250–500 mg/day every 1–3 days, to serum concentrations of 45–125 μg/mL. Of note, sedation, increased appetite, and reductions in white blood cell counts and platelet counts all become more frequent at serum concentrations greater than 100 μg/mL (Bowden et al. 2000).

Mechanism of Action

Valproate stimulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and indirectly inhibits glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) (Cournoyer and Desrosiers 2009). Valproate also stimulates the activity of bcl-2, a neuroprotective substance (Gray et al. 2003). Valproate inhibits histone deacetylase, and many of the drug’s subcellular effects (e.g., increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor) are likely a consequence of this action (Harwood and Agam 2003; Perova et al. 2010).

Indications and Efficacy

Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder

In a placebo-controlled study, patients with more severe manic symptoms experienced greater benefits from valproate versus placebo than did patients with milder manic symptomatology (Bowden et al. 2006). In this study, the antimanic response to valproate occurred as early as 5 days following initiation of treatment.

Valproate has been studied in adjunctive regimens with various antipsychotics, with findings consistently pointing to greater efficacy for combination treatment than for monotherapy (Bowden 2011; Marcus et al. 2011; Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 2000; Tohen et al. 2002; Yatham et al. 2003). A 3-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study (Sachs et al. 2002) evaluated the efficacy of risperidone or haloperidol in combination with a mood stabilizer in two groups of bipolar patients: 1) patients who had received treatment with either valproate or lithium at an adequate dosage for at least 2 weeks and were still manic (in which case they were randomly assigned to add-on treatment with risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo) and 2) patients who were manic but had not yet received mood stabilizer treatment (in which case either lithium or valproate was started concurrently with randomization to the add-on treatment). Patients who started mood stabilizer treatment on entering the study showed no advantage from the add-on antipsychotic, whereas patients who were already receiving valproate or lithium but were still symptomatic at study entry did demonstrate an advantage from the combination treatment (Sachs et al. 2002). These findings suggest that in most circumstances, combination therapy is most effective in—and should be limited to—patients whose symptoms have not responded to a relatively short period of adequate monotherapy treatment.

Few studies of any antimanic agent have addressed its effectiveness in hypomanic episodes, which are more common than manic episodes, even in diagnostically bipolar I patients. In an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in outpatients with bipolar and related disorders manifesting hypomanic symptomatology (operationalized as a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score between 10 and 20), divalproex ER was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing hypomanic/mild manic symptoms (P=0.024) and nonsignificantly more effective than placebo in improving depression (McElroy et al. 2010).

Acute Depression in Bipolar Disorder

An 8-week randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded study reported that divalproex-treated subjects experienced significantly greater improvement than placebo-treated patients in both depressive and anxious symptomatology, based on Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Ham-A) scores (Davis et al. 2005).

In a 6-week randomized, blinded study in bipolar depression, divalproex was superior to placebo, with primary improvement noted on core mood symptoms rather than on anxiety or insomnia (Ghaemi et al. 2007). Smith et al. (2010) conducted a meta-analysis of these and two other small randomized, blinded studies in acute bipolar depression and found significant reductions in depression scale scores for valproate compared with placebo (standardized mean difference: −0.35; range: −0.69 to −0.02). Tolerability was good, but improvement of anxiety was modest and not significant. Valproate also has shown significant prophylactic benefit in reducing risk of relapse to depression, both as monotherapy and as an adjunct to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment. In a 1-year randomized, double-blind study of bipolar patients who were initially manic, divalproex was more effective than lithium or placebo in delaying time to clinical depression (Gyulai et al. 2003). In those subjects who developed depression, divalproex augmented with either paroxetine or sertraline was superior to either antidepressant alone in treatment of the depression (Gyulai et al. 2003). Ketter et al. (2011) calculated a number needed to treat (NNT) of 11 for divalproex in prevention of bipolar depression; by comparison, an NNT of 49 was calculated for lithium, 15 for lamotrigine, 12 for olanzapine, and 64 for aripiprazole (Ketter et al. 2011).

Maintenance Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

One large double-blind, placebo-controlled maintenance study of valproate monotherapy has been published (Bowden et al. 2000). Patients who recovered with open treatment with either divalproex or lithium were randomly assigned to maintenance treatment with divalproex, lithium, or placebo. The divalproex group did not differ significantly from the placebo group on time to any mood episode (P=0.06), in part because the rate of relapse to mania with placebo was lower than anticipated. However, a post hoc analysis of the study data found that divalproex was superior to placebo on secondary outcome measures, with lower rates of discontinuation for either any recurrent mood episode or a depressive episode (Bowden 2004). Divalproex was superior to lithium on some comparisons, including longer duration of successful prophylaxis in the study and less deterioration in depressive symptom scores. Among the subset of patients who received divalproex in the open acute phase, those randomly assigned to receive divalproex in the double-blind maintenance phase had significantly longer times to recurrence of any mood episode (P=0.05) or a depressive episode (P=0.03), and the proportion of patients who completed the 1-year study without developing either a manic or a depressive episode was significantly higher for divalproex-treated patients than for placebo-treated patients (41% vs. 13%; P=0.01) (Bowden et al. 2000). This study (Bowden et al. 2000) is the only investigation published to date that has allowed a statistical test of the relation between acute-episode response to treatment and maintenance treatment outcomes. A post hoc review of the study that used relative risk analysis found that patients taking divalproex were significantly less likely than those taking placebo to have prematurely left the study because of a mood episode (relative risk [RR]=0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.44–0.90) (Bowden 2004). A post hoc analysis of time to any mood episode or early discontinuation for any reason, a measure of effectiveness that has been incorporated in more recent maintenance studies in bipolar disorder, indicated a significant advantage for divalproex over lithium (P>0.004) (Bowden 2003a).

A comparison of valproate and lithium in a randomized, blinded trial of rapid-cycling patients reported that only one-quarter of the patients enrolled met criteria for an acute bimodal response to either drug, with fewer than 25% of the patients who entered the randomized maintenance phase retaining benefit without relapse for the entire 20-month period. These findings indicate that monotherapy regimens with either valproate or lithium are unlikely to be effective in more than a small minority of rapid-cycling patients (Calabrese et al. 2005).

Additional evidence of the low likelihood of maintaining remission comes from a study of bipolar patients with a recently remitted manic episode who were followed up for 6 months of continuation valproate or lithium plus adjunctive therapy consisting of random assignment to either olanzapine or risperidone. The adjunctive therapy reduced the proportion relapsed among patients randomized to olanzapine, but not among patients randomized to risperidone (Yatham et al. 2016). In a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled maintenance treatment studies in bipolar disorder, lithium plus valproate seemed to be more effective in preventing manic episodes than in preventing depressive episodes. Lamotrigine appeared to be more protective against depressive episodes. The analyses suggested that the combination was likely to be superior to either drug alone (Miura et al. 2014).

Older adults with bipolar disorder have high rates of hospitalization for medical conditions. In a large cohort study of bipolar patients ages 66 years or older who had recently been discharged from a psychiatric hospitalization, 1-year rates of acute medical, nonpsychiatric health use did not differ according to which medication—lithium, valproate, or another agent (e.g., antipsychotics)—patients were receiving (Rej et al. 2015). Along with male sex and a history of medical hospitalization, severity of mental illness (e.g., being hospitalized for bipolar disorder) may be a more important driver of future acute medical health service use compared with choice of pharmacotherapy. A proactive collaborative approach with primary care and home care may potentially prevent intensive acute medical health service use in older adults with bipolar disorder and other severe mental illnesses.

Over the past decade, more studies employing enriched designs in adjunctive treatment have been conducted for all drugs. Such studies are more likely to yield superiority for the adjunctive regimen, because the only patients eligible are those who have failed to respond to monotherapy regimens. Most of these studies have added atypical antipsychotics—or, in one case, lamotrigine—to regimens of valproate or lithium. Despite the design inequality, the designs have the merit of following a common pattern of clinical practice. In all of these studies, valproate has been adequately tolerated along with the added drug. In most adjunctive design studies, no separate analysis of the results for valproate and lithium has been reported. In a study of adjunctive ziprasidone or placebo added to the regimens of patients who continued to have manic symptoms while taking valproate or lithium, the adjunctive therapy was superior to continued lithium monotherapy, whereas the outcome of valproate monotherapy was equal to that of valproate plus ziprasidone (Bowden 2011).

A 12-week randomized, blinded comparison of valproate and olanzapine showed equivalent efficacy in mania for the two treatments (Zajecka et al. 2002). A 47-week study of the two drugs reported low rates of completion for both treatments (15% vs. 16%), with earlier symptomatic remission with olanzapine but equivalent efficacy for the two drugs over the remaining portion of the study (Tohen et al. 2003). For both drugs, patients who were in remission at the end of week 3 of treatment were significantly more likely to complete the 47-week trial compared with those who were not in remission at that point (divalproex: 26.2% vs. 11.1%; olanzapine: 20.3% vs. 10.6%; P=0.001). This finding indicates that acute treatment response to a drug (either valproate or olanzapine) during a manic episode is predictive of effective treatment with that drug in maintenance therapy. In both studies, weight gain was greater with olanzapine than with divalproex, and divalproex was associated with a significant reduction in cholesterol levels, compared with an increase in cholesterol levels with olanzapine (Tohen et al. 2003; Zajecka et al. 2002).

Mania Secondary to Head Trauma or Neurodevelopmental/Neurodegenerative Disorders

Evidence suggesting that secondary or complicated mania responds well to valproate is mixed. In an open study of 56 valproate-treated patients with mania, response was associated with the presence of nonparoxysmal abnormalities on the electroencephalogram, but not with neurological soft signs or abnormalities on computed axial tomography scans of brain (McElroy et al. 1988). A study from the 1980s (Pope et al. 1988) had suggested that manic patients who had experienced a closed-head injury before the onset of bipolar disorder were more likely to respond successfully to valproate treatment for mood symptoms. Furthermore, case reports have described successful valproate treatment of mood symptoms in individuals with DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980) organic brain syndromes (Kahn et al. 1988) and of bipolar symptoms in patients with DSM-III mental retardation (Kastner et al. 1990; Sovner 1989).

Bipolar Disorder in Children and Adolescents

Few adequately powered and designed studies have been conducted in pediatric bipolar disorder. Findings from the first placebo-controlled trial of divalproex in bipolar children and adolescents (ages 10–17 years) indicated that divalproex was not significantly superior to placebo, and side effects were similar for divalproex and placebo (Wagner et al. 2009).

In the only blinded, randomized study to compare two medications in young adolescent patients with bipolar disorder, risperidone compared with valproate showed somewhat earlier onset of improvement and resulted in a higher proportion of patients responding by the end of the 6-week trial (Pavuluri et al. 2010). This study lacked a placebo control group.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms are commonly intertwined with specific symptoms of bipolar disorder in youth. In a pragmatic study of 40 patients between the ages of 6 and 17 years with bipolar I (77%) or bipolar II (23%) disorder, YMRS scores of 14 or greater, and ADHD symptomatology, subjects were first given divalproex. Thirty-two subjects achieved improvement of 50% or greater on YMRS scores, whereas only 3 showed improvement in ADHD symptoms. Mixed amphetamines or placebo were then added to the regimens of the 30 subjects who entered the placebo crossover phase. Amphetamines plus divalproex were superior to divalproex alone in improving ADHD symptoms. Both regimens were well tolerated, and no patient experienced worsening of manic symptoms (Scheffer et al. 2005).

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study in children ages 8–10 years who met criteria for oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder and had experienced temper and mood lability but did not meet full criteria for bipolar disorder, patients were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of divalproex or placebo, followed by 6 weeks of placebo or divalproex (in a crossover design). By the end of the first phase, 8 of the 10 patients who received divalproex had responded, compared with none of those who received placebo. Of the 15 patients who completed both phases, 12 had superior responses to divalproex (Donovan et al. 2000).

Agitation and Clinical Decline in Elderly Patients With Dementia

Patients with dementia are frequently institutionalized for agitation and behavioral disturbances. In a randomized, blinded study in which 56 nursing home patients with agitation and dementia received either placebo or individualized doses of divalproex, the drug–placebo difference on Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Agitation scores significantly favored divalproex. Side effects occurred in 68% of the divalproex group versus 33% of the placebo group and were generally rated as mild (Porsteinsson et al. 2001). Six weeks of open continuation treatment resulted in further improvement of agitation. Divalproex serum levels were greater than 40 μg/mL in both the acute blinded phase and the open continuation phase (Porsteinsson et al. 2003). Patients with dementia should generally receive valproate dosages lower than 1,000 mg/day to ensure adequate tolerability (Profenno et al. 2005). A small randomized, placebo-controlled study of valproate in the treatment of aggression in dementia failed to find any difference between valproate and placebo, although the fixed dosage used (valproate 480 mg/day) may have been inadequate (Sival et al. 2002).

Valproate also was studied for its potential utility in preventing or delaying illness progression in 313 nursing home residents with moderate Alzheimer’s disease who had not yet experienced agitation or psychosis. Time to emergence of clinically significant agitation or psychosis did not differ between valproate and placebo groups, and valproate was associated with serious adverse effects in the patients (Tariot et al. 2011). Taken in the aggregate, these studies suggest that although valproate at relatively low dosages can improve dementia-related agitation in some patients, valproate has no utility in slowing or preventing disease progression in Alzheimer’s dementia.

Irritability and Aggression

Valproate has been reported to be effective in reducing irritability and aggression among diverse patient populations, including individuals with autism spectrum disorders or personality disorders. In a 12-week double-blind study of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, irritability measures were significantly improved with divalproex compared with placebo. Overall, 62% of the divalproex-treated subjects versus 9% of the placebo subjects (odds ratio=16.7) were responders (Hollander et al. 2010).

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study, 249 patients with Cluster B personality disorders, intermittent explosive disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder were treated for 12 weeks with either divalproex or placebo. Although divalproex did not separate from placebo in the combined analysis of all patient groups, aggression and irritability scores among the 96 Cluster B patients showed significant improvement over the course of the study (Hollander et al. 2003).

Co-Therapy in Schizophrenia

Adjunctive use of valproate in the treatment of schizophrenia has increased, with one report indicating that more than one-third of psychiatric inpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia received valproate during hospitalization (Citrome et al. 2000). In a 4-week randomized, double-blind study, 242 schizophrenic patients were assigned to receive either monotherapy with an antipsychotic (risperidone or olanzapine) or adjunctive treatment with divalproex plus the antipsychotic drug. Compared with patients receiving monotherapy, those who received combination therapy showed significantly greater improvement on Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)–Total and PANSS positive symptom subscale scores from day 3 through day 21, but not at day 28. Platelet counts decreased with combination therapy. Cholesterol levels increased with olanzapine or risperidone monotherapy compared with the significantly lower levels seen with the combination treatment. Weight gain did not differ for patients receiving olanzapine versus patients receiving divalproex plus olanzapine; however, weight gain was greater for divalproex plus risperidone (7.5 lbs) than for risperidone (4.2 lbs) (Casey et al. 2003).

Bipolar Disorder With Comorbid Alcohol Use Disorder

Bipolar disorder is often associated with substance use disorders, particularly alcoholism. In the largest prospective, blinded, placebo-controlled study, 59 bipolar I patients with DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) alcohol dependence were treated with lithium carbonate and psychosocial interventions for 24 weeks, with half randomly assigned to receive adjunctive valproate. The addition of valproate was associated with significantly fewer heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per heavy drinking day, and fewer drinks per drinking day. Higher serum valproate concentrations were correlated with improved alcohol use outcomes. Both manic and depressive symptoms improved equivalently (Salloum et al. 2005).

In a 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, divalproex treatment was associated with a significantly reduced rate of relapse to heavy drinking, but no significant differences were found in other alcohol-related outcomes. Significantly greater decreases in irritability were found in the divalproex-treated group, but no significant between-group differences were seen on measures of impulsivity (Brady et al. 2002).

Predictors of Positive Response to Valproate Versus Lithium

Mixed Mania

Patients with mixed manic presentations experienced greater symptom improvement with divalproex than with lithium treatment in two randomized studies (Freeman et al. 1992; Swann et al. 1997), one of which (Swann et al.) was placebo controlled (reviewed in Bowden 1995). Patients with mixed manic symptoms and patients with pure manic symptoms showed equivalent improvement with divalproex, a finding that indicates the drug’s broad efficacy across mania subtypes (Swann et al. 1997). By contrast, during maintenance treatment, patients with mixed mania had equivalent responses to divalproex and lithium, with evidence of higher rates of adverse effects as a function of illness features of mixed mania, compared with rates of adverse effects in patients with euphoric mania (Bowden et al. 2005; Singh et al. 2013). These results suggest that effective long-term management of mixed manic states requires medication regimens that are more complex than monotherapy.

High Lifetime Number of Mood Episodes

Divalproex was significantly more effective than lithium among manic patients with a history of more than 10 mood episodes (Swann et al. 1999) or more than two depressive episodes (Swann et al. 2000).

Side Effects and Toxicology

Valproate has been extensively used over several decades; thus, its adverse-effect profile is well characterized (DeVane 2003; Prevey et al. 1996). Compared with patients treated for migraine or mania, patients treated for epilepsy are more likely to experience adverse events consequent to the generally higher dosages of valproate required and the more complex drug regimens used in epilepsy. In a large 1-year placebo-controlled study in patients with bipolar disorder, tremor and weight gain were the only symptoms more commonly reported with divalproex than with placebo (DeVane 2003).

Gastrointestinal Effects

Common gastrointestinal effects of valproate include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspepsia, and anorexia. These are dose dependent, are usually encountered at the start of treatment, and are often transient (DeVane 2003). Immediate-release formulations of valproic acid are more likely than ER and enteric-coated formulations to cause adverse events (Horne and Cunanan 2003; Zarate et al. 1999).

Tremor

Tremor consequent to valproate resembles benign essential tremor and may respond to a reduction in dosage. Use of the ER or enteric-coated formulation may lessen the frequency of tremor (Wilder 1992; Zarate et al. 1999).

Sedation

Mild sedation is common at initiation of valproate treatment. This adverse effect is dose dependent and may be minimized by dosage reduction, slower titration, use of ER formulations, or taking all medication at bedtime.

Pancreatitis

Idiosyncratic acute pancreatitis is an infrequent adverse event associated with valproate. In clinical trials, rates of amylase elevation with valproate were similar to those with placebo (Pellock et al. 2002), suggesting that precautionary amylase levels offer little benefit in predicting pancreatitis. Therefore, clinicians should routinely assess patients’ clinical symptoms to identify possible signs of pancreatitis.

Hematological Effects

Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are directly related to higher valproate serum levels, usually 100 μg/mL or greater (Acharya and Bussel 1996; Bowden et al. 2000). Thrombocytopenia is usually mild and rarely associated with bleeding complications. Management consists of dosage reduction. Platelet counts below 75,000/mm3 should be monitored and regularly reassessed, because counts lower than this level are more frequently associated with bruising or bleeding (Zarate et al. 1999).

Hepatotoxicity

None of the longer-term studies of the past decade and a half has found evidence of hepatic dysfunction or significant worsening of hepatic indices in valproate-treated patients compared with placebo-treated or comparator-treated patients (Bowden et al. 2000; Tohen et al. 2002; Zajecka et al. 2002).

The risk of liver toxicity from valproate is largely limited to patients younger than 2 years, in whom hepatic function is still immature (Tohen et al. 2003). In a long-term study of divalproex (versus lithium) in adult outpatients with bipolar I disorder, full-dosage regimens for 1 year were associated with improvements in laboratory indices of hepatic function, and no hepatotoxicity was reported in the 187 patients taking divalproex (Bowden et al. 2000). A 47-week placebo-controlled study of olanzapine augmentation of divalproex or lithium in outpatients with bipolar disorder likewise found no evidence of adverse hepatic effects among patients who received divalproex (Tohen et al. 2003).

One risk factor for the development of hepatotoxicity is concomitant administration of other anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin) that cause induction of enzymes involved in the metabolism of valproate, leading to increased concentrations of an active and hepatotoxic metabolite, 2-propyl-4-pentenoic acid.

Weight Gain

Weight gain of 3–24 lbs is seen in 3%–20% of patients taking valproic acid for periods ranging from 3 to 12 months (Bowden 2003b). Weight gain has been consistently less with valproate than with olanzapine in comparison studies (1.22 kg vs. 2.79 kg) (Tohen et al. 2003; Zajecka et al. 2002). Valproate serum levels greater than 125 μg/mL are more likely than lower levels to cause weight gain (Bowden 2000). If increased appetite and weight gain occur with valproate, the dosage should be lowered so long as clinical effectiveness is maintained; alternatively, valproate should be discontinued and replaced with a regimen without risk of weight gain.

Cognitive Effects

Valproate infrequently produces adverse effects on cognitive functioning, and it improves cognition in some patients (Prevey et al. 1996). In a 20-week randomized, observer-blinded, parallel-group trial, the addition of valproate to carbamazepine resulted in improvement in short-term verbal memory (Aldenkamp et al. 2000). No adverse cognitive effects associated with use of valproate were seen in a group of elderly patients (mean age=77 years) (Craig and Tallis 1994).

Lipid Profile Effects

Several studies indicate that valproate significantly reduces total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and increases high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels in long-term treatment (Geller et al. 2012), and that it protects against the adverse effects of some antipsychotic drugs on lipid function (Bowden et al. 2000; Casey et al. 2003; Tohen et al. 2003). A 3-week study in mania indicated reductions in cholesterol, HDL, and LDL compared with placebo and reported the effect to be limited to those subjects who had total cholesterol levels of 200 mg/dL or greater at study entry (Bowden et al. 2006).

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

The prevalence of menstrual disturbances in women with bipolar disorder is higher than that in the general population. A cross-sectional study of women found evidence of a higher rate of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) in subjects who reported valproate as a component of their prior treatment regimen (Joffe et al. 2006). A study of 10 lithium-treated, 10 valproate-treated, and 2 carbamazepine-treated women with bipolar disorder found a high frequency of menstrual dysfunction in all groups. Hormonal assessment of estrone, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) yielded no abnormal values in any patient (Rasgon et al. 2000). Obesity may be a mechanistic pathway whereby valproate (and potentially other drugs) predisposes women to PCOS. It is advisable to treat weight gain as a risk factor for possible development of PCOS and intervene as needed to avoid clinically significant weight gain.

Hair Loss

Hair loss may occur early in treatment and is usually transient. Frequency of hair loss may be greater in women than in men (Lajee and Parsonage 1980). Dosage reduction and separation of valproate dosing from meals can be helpful in controlling this effect; supplemental zinc and selenium ingestion via multivitamin tablets also may be useful.

Use During Pregnancy and Lactation

Teratogenic and Developmental Effects

Valproate is associated with an increased incidence of birth defects, including neural tube defects, craniofacial anomalies, limb abnormalities, and cardiovascular anomalies, if infants are exposed to valproic acid in the first 10 weeks of gestation (Kinrys et al. 2003; Samrén et al. 1997). Neural tube defects, the most serious of the congenital anomalies, occur in 1%–4% of such infants. Most of the available data involved patients with epilepsy, who generally receive valproate dosages higher than those used for bipolar disorder and migraine and who are often concurrently taking other teratogenic anticonvulsants (Bowden 2003b). The risk of malformations is increased with higher dosages and higher serum levels of valproate, as well as with concomitant use of other anticonvulsants (because of higher concentrations of 2-propyl-4-pentenoic acid, a teratogenic agent); is possibly decreased with supplemental folic acid; and is definitely reduced with lower dosages of valproate (Bowden 2003b). The inhibitory effect of valproate on histone deacetylase, linked to Wnt signaling, which is involved in cell division, is a plausible mechanism by which teratogenic effects could develop.

Because alternative treatment strategies lacking teratogenic risk are available that can effectively manage bipolar symptoms, valproate should generally be discontinued in patients who are trying to conceive, and if pregnancy occurs, valproate should not be reinstated until after the first trimester.

Cognitive effects of prenatal exposure to valproate have been found. When assessed at age 3 years, children who had experienced fetal exposure to valproate had IQ scores 6–9 points lower than those of children who had fetal exposure to lamotrigine, carbamazepine, or phenytoin (Meador et al. 2009).

Breast Feeding

Valproate is minimally present in breast milk. Piontek et al. (2000) reported that among six mother–infant pairs, serum valproate levels in the infants ranged from 0.9% to 2.3% of the mother’s serum levels, with absolute serum levels of 0.7–1.56 μg/mL. The valproate concentration in an infant was 1.5% of the maternal concentration (Wisner and Perel 1998).

Overdose

Recovery from overdose-induced coma has occurred with serum valproate concentrations greater than 2,000 μg/mL. In addition, serum valproate concentrations have been reduced by hemodialysis and hemoperfusion, and valproate-induced coma has been reversed with naloxone (Rimmer and Richens 1985).

Drug–Drug Interactions

Because valproate is highly protein bound and extensively metabolized by the liver, a number of potential interactions may occur with other protein-bound or extensively metabolized drugs (Fogel 1988; Rimmer and Richens 1985). Thus, free fraction concentrations of valproate in serum can be increased, and valproate toxicity can be precipitated, by coadministration of other highly protein-bound drugs (e.g., aspirin) that can displace valproate from its protein-binding sites.

In the context of coadministration, valproate’s competitive inhibition of lamotrigine excretion via glucuronidation requires that lamotrigine be started at a lower dosage—usually 25 mg every other day—with increases implemented cautiously. Lamotrigine’s steady-state plasma concentrations are also generally lower when the drug is used with valproate, although not in all patients.

Conclusion

Valproate’s broad spectrum of efficacy in bipolar and related disorders and generally good tolerability make it a foundation of treatment for many patients with bipolar disorders. For optimal results, most patients should be treated with the formulation that permits once-daily dosing and has the lowest peak-to-trough serum level, which in the United States currently is divalproex ER. Although onset of action of valproate occurs quickly with use of loading-dose strategies, gradual dosage titration is the preferred method of treatment initiation for all but the most severe manic states. Medication tolerability is of paramount importance in fostering patient adherence to long-term treatment regimens.

During maintenance treatment, it is often necessary to reduce the dosage if adverse effects persist. Valproate is principally effective in and prophylactic for manic symptoms, although its prophylactic benefits in depression are now relatively well established. A history of multiple affective episodes or a current presentation characterized by irritability may be a particularly strong indicator of a favorable response to valproate. Although some patients may achieve acute and sustained remission with valproate monotherapy, many patients are more effectively treated with combinations, including other mood stabilizers and adjunctive medications. All current medications with established or putative roles in bipolar disorder can be combined with valproate.

References

Acharya S, Bussel JB: Hematologic toxicity of sodium valproate. J Pediatr Neurol 14:303–307, 1996

Aldenkamp AP, Baker G, Mulder OG, et al: A multicenter, randomized clinical study to evaluate the effect on cognitive function of topiramate compared with valproate as add-on therapy to carbamazepine in patients with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia 41(9):1167–1178, 2000 10999556

Allen MH, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ, et al: Linear relationship of valproate serum concentration to response and optimal serum levels for acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 163(2):272–275, 2006 16449481

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1980

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Bocci U, Beretta G: Esperienze sugli alcoolisti e tossicomania con dipropilacetate di sodio. Lavoro Neuropsichiatrico 58:51–61, 1976

Bowden CL: Predictors of response to divalproex and lithium. J Clin Psychiatry 56 (suppl 3):25–30, 1995 7883739

Bowden CL: Valproate in mania, in Bipolar Medications: Mechanisms of Action. Edited by Manji HK, Bowden CL, Belmaker RH. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2000, pp 357–365

Bowden CL: Acute and maintenance treatment with mood stabilizers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 6(3):269–275, 2003a 12974993

Bowden CL: Valproate. Bipolar Disord 5(3): 189–202, 2003b 12780873

Bowden CL: Relationship of acute mania symptomatology to maintenance treatment response. Curr Psychiatry Rep 6(6):473–477, 2004 15538997

Bowden CL: The role of ziprasidone in adjunctive use with lithium or valproate in maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 7:87–92, 2011 21552310

Bowden CL, Janicak PG, Orsulak P, et al: Relation of serum valproate concentration to response in mania. Am J Psychiatry 153(6):765–770, 1996 8633687

Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, et al; Divalproex Maintenance Study Group: A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57(5):481–489, 2000 10807488

Bowden CL, Collins MA, McElroy SL, et al: Relationship of mania symptomatology to maintenance treatment response with divalproex, lithium, or placebo. Neuropsychopharmacology 30(10):1932–1939, 2005 15956987

Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, et al; Depakote ER Mania Study Group: A randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended release in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 67(10):1501–1510, 2006 17107240

Brady KT, Myrick H, Henderson S, et al: The use of divalproex in alcohol relapse prevention: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend 67(3):323–330, 2002 12127203

Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Rapport DJ, et al: A 20-month, double-blind, maintenance trial of lithium versus divalproex in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 162(11):2152–2161, 2005 16263857

Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, et al: Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 28(1):182–192, 2003 12496955

Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B: Changes in use of valproate and other mood stabilizers for patients with schizophrenia from 1994 to 1998. Psychiatr Serv 51(5):634–638, 2000 10783182

Cournoyer P, Desrosiers RR: Valproic acid enhances protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase expression by stimulating extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway. Neuropharmacology 56(5):839–848, 2009 19371592

Craig I, Tallis R: Impact of valproate and phenytoin on cognitive function in elderly patients: results of a single-blind randomized comparative study. Epilepsia 35(2):381–390, 1994 8156961

Davis LL, Bartolucci A, Petty F: Divalproex in the treatment of bipolar depression: a placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord 85(3):259–266, 2005 15780695

DeVane CL: Pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and tolerability of valproate. Psychopharmacol Bull 37 (suppl 2):25–42, 2003 14624231

Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al: Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry 157(5):818–820, 2000 10784478

Fogel BS: Combining anticonvulsants with conventional psychopharmacologic agents, in Use of Anticonvulsants in Psychiatry: Recent Advances. Edited by McElroy SL, Pope HG Jr. Clifton, NJ, Oxford Health Care, 1988, pp 77–94

Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, et al: A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 149(1):108–111, 1992 1728157

Geller B, Luby JL, Joshi P, et al: A randomized controlled trial of risperidone, lithium, or divalproex sodium for initial treatment of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed phase, in children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(5):515–528, 2012 22213771

Ghaemi SN, Gilmer WS, Goldberg JF, et al: Divalproex in the treatment of acute bipolar depression: a preliminary double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 68(12):1840–1844, 2007 18162014

Gray NA, Zhou R, Du J, et al: The use of mood stabilizers as plasticity enhancers in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 64 (suppl 5):3–17, 2003 12720479

Grunze H, Erfurth A, Amann B, et al: Intravenous valproate loading in acutely manic and depressed bipolar I patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 19(4):303–309, 1999 10440456

Gyulai L, Bowden CL, McElroy SL, et al: Maintenance efficacy of divalproex in the prevention of bipolar depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 28(7):1374–1382, 2003 12784116

Harwood AJ, Agam G: Search for a common mechanism of mood stabilizers. Biochem Pharmacol 66(2):179–189, 2003 12826261

Hollander E, Tracy KA, Swann AC, et al: Divalproex in the treatment of impulsive aggression: efficacy in cluster B personality disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 28(6):1186–1197, 2003 12700713

Hollander E, Chaplin W, Soorya L, et al: Divalproex sodium vs placebo for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(4):990–998, 2010 20010551

Horne RL, Cunanan C: Safety and efficacy of switching psychiatric patients from a delayed-release to an extended-release formulation of divalproex sodium. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23(2):176–181, 2003 12640219

Jacobsen FM: Low-dose valproate: a new treatment for cyclothymia, mild rapid cycling disorders, and premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry 54(6):229–234, 1993 8331092

Joffe H, Cohen LS, Suppes T, et al: Valproate is associated with new-onset oligoamenorrhea with hyperandrogenism in women with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 59(11):1078–1086, 2006 16448626

Kahn D, Stevenson E, Douglas CJ: Effect of sodium valproate in three patients with organic brain syndromes. Am J Psychiatry 145(8):1010–1011, 1988 3394852

Kastner T, Friedman DL, Plummer AT, et al: Valproic acid for the treatment of children with mental retardation and mood symptomatology. Pediatrics 86(3):467–472, 1990 2117744

Keck PE Jr, Bowden CL, Meinhold JM, et al: Relationship between serum valproate and lithium levels and efficacy and tolerability in bipolar maintenance therapy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 9(4):271–277, 2005 24930925

Ketter TA, Citrome L, Wang PW, et al: Treatments for bipolar disorder: can number needed to treat/harm help inform clinical decisions? Acta Psychiatr Scand 123(3):175–189, 2011 21133854

Kinrys G, Pollack MH, Simon NM, et al: Valproic acid for the treatment of social anxiety disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 18(3):169–172, 2003 12702897

Lajee HCK, Parsonage MJ: Unwanted effects of sodium valproate in the treatment of adult patients with epilepsy, in The Place of Sodium Valproate in the Treatment of Epilepsy. Edited by Parsonage NJ, Caldwell ADS. London, Royal Society of Medicine, 1980, pp 141–158

Lambert PA, Carraz G, Borselli S, et al: [Neuropsychotropic action of a new anti-epileptic agent: depamide]. Ann Med Psychol (Paris) 124(5):707–710, 1966 5941463

Levy MN: Cardiac sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions. Fed Proc 43(11):2598–2602, 1984 6745448

Marcus R, Khan A, Rollin L, et al: Efficacy of aripiprazole adjunctive to lithium or valproate in the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder with an inadequate response to lithium or valproate monotherapy: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study. Bipolar Disord 13(2):133–144, 2011 21443567

McElroy SL, Pope HG Jr, Keck PE Jr: Treatment of psychiatric disorders with valproate: a series of 73 cases. Psychiatr Psychobiol 3:81–85, 1988

McElroy SL, Martens BE, Creech RS, et al: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of divalproex extended release loading monotherapy in ambulatory bipolar spectrum disorder patients with moderate-to-severe hypomania or mild mania. J Clin Psychiatry 71(5):557–565, 2010 20361901

Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al; NEAD Study Group: Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med 360(16):1597–1605, 2009 19369666

Miura T, Noma H, Furukawa TA, et al: Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 1(5):351–359, 2014 26360999

Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Retzow A, Henn FA, et al; European Valproate Mania Study Group: Valproate as an adjunct to neuroleptic medication for the treatment of acute episodes of mania: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 20(2):195–203, 2000 10770458

Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Findling RL, et al: Double-blind randomized trial of risperidone versus divalproex in pediatric bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 12(6):593–605, 2010 20868458

Pellock JM, Wilder BJ, Deaton R, et al: Acute pancreatitis coincident with valproate use: a critical review. Epilepsia 43(11): 1421–1424, 2002 12423394

Perova T, Kwan M, Li PP, Warsh JJ: Differential modulation of intracellular Ca2+ responses in B lymphoblasts by mood stabilizers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 13(6):693–702, 2010 19400980

Piontek CM, Baab S, Peindl KS, et al: Serum valproate levels in 6 breastfeeding mother-infant pairs. J Clin Psychiatry 61(3):170–172, 2000 10817100

Pope HG Jr, McElroy SL, Satlin A, et al: Head injury, bipolar disorder, and response to valproate. Compr Psychiatry 29(1):34–38, 1988 3125002

Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Erb R, et al: Placebo-controlled study of divalproex sodium for agitation in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 9(1):58–66, 2001 11156753

Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Jakimovich LJ, et al: Valproate therapy for agitation in dementia: open-label extension of a double-blind trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 11(4):434–440, 2003 12837672

Prevey ML, Delaney RC, Cramer JA, et al: Effect of valproate on cognitive functioning: comparison with carbamazepine. The Department of Veteran Affairs Epilepsy Cooperative Study 264 Group. Arch Neurol 53(10):1008–1016, 1996 8859063

Profenno LA, Jakimovich L, Holt CJ, et al: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial of safety and tolerability of two doses of divalproex sodium in outpatients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2(5):553–558, 2005 16375658

Rasgon NL, Altshuler LL, Gudeman D, et al: Medication status and polycystic ovary syndrome in women with bipolar disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry 61(3):173–178, 2000 10817101

Rej S, Yu C, Shulman K, et al: Medical comorbidity, acute medical care use in late-life bipolar disorder: a comparison of lithium, valproate, and other pharmacotherapies. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 37(6):528–532, 2015 26254672

Rimmer EM, Richens A: An update on sodium valproate. Pharmacotherapy 5(3):171–184, 1985 3927267

Sachs GS, Grossman F, Ghaemi SN, et al: Combination of a mood stabilizer with risperidone or haloperidol for treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of efficacy and safety. Am J Psychiatry 159(7):1146–1154, 2002 12091192

Salloum IM, Cornelius JR, Daley DC, et al: Efficacy of valproate maintenance in patients with bipolar disorder and alcoholism: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(1):37–45, 2005 15630071

Samrén EB, van Duijn CM, Koch S, et al: Maternal use of antiepileptic drugs and the risk of major congenital malformations: a joint European prospective study of human teratogenesis associated with maternal epilepsy. Epilepsia 38(9):981–990, 1997 9579936

Scheffer RE, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, et al: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mixed amphetamine salts for symptoms of comorbid ADHD in pediatric bipolar disorder after mood stabilization with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry 162(1):58–64, 2005 15625202

Singh V, Bowden CL, Gonzalez JM, et al: Discriminating primary clinical states in bipolar disorder with a comprehensive symptom scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 127(2):145–152, 2013 22774941

Sival RC, Haffmans PM, Jansen PA, et al: Sodium valproate in the treatment of aggressive behavior in patients with dementia—a randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17(6): 579–585, 2002 12112183

Smith LA, Cornelius VR, Azorin JM, et al: Valproate for the treatment of acute bipolar depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 122(1–2):1–9, 2010 19926140

Sovner R: The use of valproate in the treatment of mentally retarded persons with typical and atypical bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 50 (suppl):40–43, 1989 2494159

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, et al: Depression during mania: treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(1):37–42, 1997 9006398

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, et al: Differential effect of number of previous episodes of affective disorder on response to lithium or divalproex in acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 156(8):1264–1266, 1999 10450271

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, et al: Mania: differential effects of previous depressive and manic episodes on response to treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101(6):444–451, 2000 10868467

Tariot PN, Schneider LS, Cummings J, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group: Chronic divalproex sodium to attenuate agitation and clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(8):853–861, 2011 21810649

Tohen M, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, et al: Efficacy of olanzapine in combination with valproate or lithium in the treatment of mania in patients partially nonresponsive to valproate or lithium monotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59(1):62–69, 2002 11779284

Tohen M, Ketter TA, Zarate CA, et al: Olanzapine versus divalproex sodium for the treatment of acute mania and maintenance of remission: a 47-week study. Am J Psychiatry 160(7):1263–1271, 2003 12832240

Wagner KD, Redden L, Kowatch RA, et al: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex extended-release in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(5):519–532, 2009 19325497

Wilder BJ: Pharmacokinetics of valproate and carbamazepine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 12 (1 suppl):64S–68S, 1992 1541720

Wisner KL, Perel JM: Serum levels of valproate and carbamazepine in breastfeeding mother-infant pairs. J Clin Psychopharmacol 18(2):167–169, 1998 9555601

Yatham LN, Grossman F, Augustyns I, et al: Mood stabilisers plus risperidone or placebo in the treatment of acute mania: international, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 182:141–147, 2003 12562742 (Erratum appears in Br J Psychiatry 182:369, 2003)

Yatham LN, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, et al: Optimal duration of risperidone or olanzapine adjunctive therapy to mood stabilizer following remission of a manic episode: a CANMAT randomized double-blind trial. Mol Psychiatry 21(8):1050–10561, 2016 26460229

Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, et al: A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 63(12):1148–1155, 2002 12523875

Zarate CAJr, Tohen M, Narendran R, et al: The adverse effect profile and efficacy of divalproex sodium compared with valproic acid: a pharmacoepidemiology study. J Clin Psychiatry 60(4):232–236, 1999 10221283