The caretakers of Kewalo Spring saw two children coming wearily along the trail. They saw the little girl stumble and fall. The boy, a little older, helped her to her feet and seemed to urge her to reach the spring. “Those two have been neglected,” one man remarked. “They look half starved, and their kapa is soiled and torn.”

“May we have water?” asked the boy when the spring was reached at last. “The trail is hot, and our water gourd is empty.” The little girl sank down on the grass as if she could go no farther. When her brother had filled his gourd she drank eagerly, then snuggled against him and fell asleep.

The kind-hearted caretakers fed the children. Later they took them into the sleeping house. “These two must come from some poor home where relatives are old or lazy,” they said to one another. “Here they can rest.”

Next morning the men woke early and went to tend their garden. As the sun rose mist blew from the mountains, and over the sleeping house a rainbow hung. “A rainbow!” said one. “Over our sleeping house! No chief—”

“The children!” his companion answered. “Who can they be?”

That day the caretakers of the spring were greatly puzzled. The children stayed as if glad of food and rest, but they did not tell their names or family, and no one came for them. Should the boy and girl be treated as young chiefs? A rainbow was a chiefly sign. The men were puzzled.

The children stayed for several days. They were quiet and often slept. The little girl especially seemed always tired.

One evening, after they had entered the sleeping house, a farmer from Makiki stopped at the spring to drink and talk. “The children of Ha‘o have run away,” he said.

“The children of the district chief?”

“Yes. Their mother died some time ago, and the new chiefess has no love for them. When Ha‘o, their father, is away she gives them little food and she is always scolding.”

“No wonder they have run away!”

“Yes,” said the man. “They are good children, a boy and his little sister. We hoped that they might find a better home, but now the chiefess is sending men to hunt for them. She has seen a rainbow down this way and says it is the rainbow of those children. Her men will find and punish those who help them.”

The caretakers of the spring looked at each other. “It may be those who help the children will not give them up,” said one in a determined voice.

“No common man can stand against the anger of that chiefess,” was the answer. After the visitor had gone the two sat talking in low voices, trying to make a plan to hide the children. At last they slept.

When all was still the boy, who like his father was called Ha‘o, rose from his mats. He took his sister in his arms and staggered with her into the moonlight. There he set her on her feet. As she woke she began to cry, but the brother hushed her. “You are the daughter of a chief,” he whispered. “You must be brave. Come.”

“Where are we going?” she asked. “I don’t want to go. I’m sleepy.”

“By and by we shall sleep,” he answered. “The chiefess is sending men to get us. Do you want to be scolded and punished again? Besides, if she finds us here she will be cruel to those who helped us. Come, O my sister. We must be far away.”

“Yes,” the little girl agreed, “she must not find us.” They followed the moonlit trail across the plain toward Kou at the mouth of the Nu‘uanu Stream. Several times the little girl said, “I am very tired,” but walked bravely on. Suddenly she stopped. “I am thirsty,” she whispered to her brother. “O Ha‘o, I must have a drink.”

Ha‘o shook his water gourd, but heard no sound. “It is empty,” he said. “I thought only that we must get away and forgot to fill my gourd. Let us go on and find another spring.”

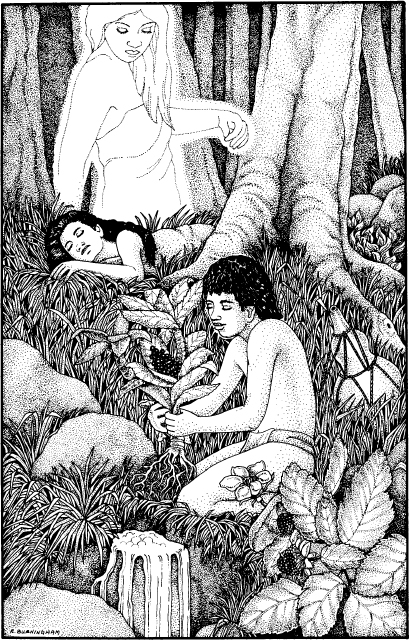

But now the little girl was crying with weariness and thirst. When she tripped over a stone and fell, Ha‘o gave up, made her comfortable on dry grass, and patted her gently until she slept. But the boy did not sleep. He too was tired and thirsty and he was deeply troubled. Where should they go? How could he get food for his sister? And water? They must have water!

With a last thirsty thought he fell asleep and, in a dream, he heard a call, “Ha‘o, O Ha‘o!” It was his mother’s voice. He saw her standing beside him just as she used to do. “You are thirsty, my children,” she said. “Pull up the bush close to your feet.” Then the form faded, and Ha‘o woke.

“It was a dream!” he thought. “Our mother came in a dream. I must obey her words.” He took hold of the bush growing near him, but it hurt his hands. He took big leaves for protection, braced himself, and pulled with all his might. Up came the bush and, where it had been, water flowed. A spring! Ha‘o filled the gourd, then woke his sister and gave her a cool drink. “It is the water of the gods,” he said. Then he too drank. “Our mother watches over us,” he whispered and, comforted, slept soundly.

When next the children woke the sun was shining. Men stood looking at them and at the spring—their father’s men! Ha‘o sprang up and greeted them with joy. He told them of his dream, and all drank from the spring.

“Come home,” the men said. “Your father longs for you.”

“The chiefess?” asked the girl in a troubled voice.

“Have no more fear of her,” the men replied. “The gods showed you this spring because of their love for you. You are their chosen ones, and the chiefess will not dare to do you harm.”

For many years that spring flowed. Its waters bubbled into a pool edged by ferns and fragrant vines. At one time a house was built over the pool to make it the bathing place for a chiefess. She too was Ha‘o, a descendant of the one who found the spring. She was a high chiefess and very sacred, very kapu. No one except her family and servants might even look at her. She might not set foot upon the ground. If she did so, the place where she had stepped would be kapu and no common person could step on it. So her servants brought her to the spring in a mānele, curtained with fine kapa. She bathed in the fern-edged pool and then was carried home. Because it was the bathing place of this young chiefess the spring came to be called The Water of Ha‘o.

That spring no longer flows for a city has grown all about it, and people pipe their water from deep wells and mountain reservoirs. Today a church stands near the place where the thirsty children drank and where the kapu chiefess bathed. The church bears the name of the spring, The Water of Ha‘o, Kawaiaha‘o.

The first part of this story was told by Emma K. Nākuina in The Friend; the second part is from a translation by Mary Kawena Pūku‘i from a Hawaiian newspaper