8

OFF THE GRID IN EGYPT — THE LIBYAN DESERT

Push yourself to your limits and see for yourself what you are capable of becoming

Speaking Arabic and knowing Cairo like the back of his hand, Alvis had booked us into a hotel in one of the less affluent parts of the city. Well, I say hotel, actually it was a filthy old brothel. But it was cheap and that’s what mattered. Even though I hadn’t had a shower for a week and hadn’t slept in a bed in the same amount of time, I was still bloody thankful that we only had to spend one night there.

Paul and Gunther were due to arrive at Cairo airport at nine that night. I remember sitting in the smelly room looking at my backpack going through the maths. Adding the figures over and over again — 20 litres of water, 3.3 kilograms of sleeping bag, 2 kilograms of food. No matter how I added it the result came to a heavy 35 kilograms. Could I walk across the desert with that on my back?

It was only a day since I finished my trek across the Arabian Desert. My legs were sore and I was exhausted. Not exactly in prime condition to tackle a long and dangerous trip. Eventually, Alvis and I went out into the streets of Cairo to get more provisions before heading for the airport. It was Ramadan in Cairo and, after nightfall, the city really came alive. The streets were chaotic with people and sounds and smells. It was a shock to my system after nine days of peace in the desert.

The poorest of the population were seated on the footpath in rows waiting for a free evening meal. Smiling children with big eyes and plastic plates waited excitedly, women with their heads shrouded in cloth sat patiently. Plates of flat bread and stew were being prepared en masse. Time and time again we were invited to join in the meal with the locals but Alvis and I had water to buy and a plane to meet so we just smiled and walked on.

Buying water to last four of us our whole trek was not an easy feat. Somehow we managed to find and purchase 45 litres of safe bottled water in a part of the city where locals drank straight from the tap. Every shop we went into, Alvis got the same reaction from the shopkeepers. ‘Forty-five litres?’ They must have thought we were crazy but after two hours we had our water ration, which we dropped off back at the ‘hotel’.

Before heading out to the airport, I packed my bag. Every single unnecessary piece was thrown out and 20 one-litre bottles of water went in, stacked in two layers. I went to try and lift my pack onto my back and Alvis caught it. ‘Stop,’ he growled. ‘No one is allowed to lift their own pack, we can’t afford a back injury in the desert.’ Suits me, I thought, I couldn’t lift it anyway. He helped me to put my pack on. And all I could think was, ‘Oh shit! You’ve got to be kidding. How the hell am I going to walk 250 kilometres across the desert with this on my back? I’m not even sure I can walk across the room.’

Having come this far there was no way I was going to back out now. Thankfully, Alvis saw that I was struggling and made some adjustments to the position of the pack leaving it sitting firmly on my hips instead of on my back. The difference it made was huge. Maybe, just maybe, I could do this after all.

By 9 pm we were out at the airport waiting for Paul and Gunther to arrive from Vienna. Well, we were at the airport but at the wrong terminal. The taxi that we’d caught out there ‘wasn’t authorised to deliver us to the other terminal’. Yeah, right. There was no way we were going to bribe the guy so Alvis and I ended up running what seemed about 3 kilometres to the other terminal, hoping like hell the plane would be late.

You should always be careful what you wish for. The plane was late. Seven hours late. To make matters worse, as we weren’t arriving or departing we weren’t allowed to stay in the terminal building. It was freezing cold outside, but there was nothing for it — we had to wait out there with everybody else.

The plane finally arrived at four in the morning, just three hours before we were due to be on a bus to Farafra, our starting point. I ran to hug Paul. Straight away it was clear he wasn’t happy. He hissed at me, ‘How dare you hug me, we’re in a Muslim country’. It didn’t matter to him that this was an airport and all around us people were hugging and kissing, happy to see each other.

Things quickly went from bad to worse. Paul reckoned he hadn’t been able to take enough water on the plane because he’d had to carry provisions for me. As a result he’d got dehydrated and now he had a cold. It was all my fault. He was in a stinking mood and there was nothing I could do about it. It hadn’t occurred to me that Paul would feel threatened but, clearly, he did. This was the first time we’d ever done an expedition with other people — much less with someone else leading the expedition. It was clear that the next few days were not going to be easy. When we got back to the brothel we had a quick briefing to make sure everything was in order. It was so late there was nothing much we could have done anyway. We left with just enough time to get to the bus station.

The ride south — nine hours in an old dunger of a bus on bumpy, dusty roads — took us deep into the Sahara. Having hardly slept in the past three days I tried to catch some shuteye but I was overtired and hyped — a lethal combination. Scarcely a word was said among our team the whole trip. We all knew the plan and talking about what we were about to do wasn’t going to help anything.

We arrived in Farafra at about four in the afternoon. This is the last town on the edge of a closed military zone that stretches south all the way to the Libyan border. We had to disappear into the desert unseen. We had no permits and there was no way we’d be able to talk ourselves out of it if we were caught. We’d be jailed as spies because we were carrying satellite pictures of the area and a primitive GPS navigation system. There were no accurate maps of the area so that’s all we had to work with. I didn’t dare to think about the consequences of such a scenario for me as a Western woman in an Islamic, Arabic country.

We had to wait until night fell before we could really make our way into the desert. Until then we just had to pretend to be tourists taking a walk on the outskirts of the town. By about six o’clock the sun started to go down and we prepared ourselves to really get moving. At this point, we thought our trip was over before it had started when three local men approached us to find out what we were doing. Alvis managed to convince them that we were just having a picnic and watching the sunset. They seemed happy with his explanation and they went on their way.

As every minute passed, the anticipation rose in me. I knew I should have been scared out of my wits but I was so focused on what was ahead of me that I was impatient for the sun to set and for us to get going. When the sun finally dropped over the horizon, we were off. Gunther and Paul helped me put on my pack with its 20 litres of water. We were going to try to do the whole trek in seven days but in case it took us longer — we’d allowed 10 days — we were rationed to 2 litres of water each a day. It might sound like quite a lot but when you’re trekking through a desert, climbing hills and tackling sandstorms, believe me, it’s not.

Alvis had been planning this trek for two years. He was undoubtedly the leader of the expedition and, as such, he had responsibility for navigation and also for keeping us all together and keeping us safe. It was pretty clear from the outset that Paul didn’t like having someone else tell him what to do. I don’t know if he’d have been the same if I wasn’t there — maybe it was just a macho thing, I’m not sure.

When we finally left the oasis and headed into the desert, it was at a fast pace. Within an hour we’d put 7 kilometres between us and town without being spotted. It was pitch black and I found myself struggling through deep sand. The terrain was quite bumpy and I couldn’t see my feet.

The reason for the bumps in the sand soon became obvious. Alvis told us all to stop and change direction. The bumps were vehicle tracks in the sand and we’d spent the past hour criss-crossing an area near a military base to try to make it hard for us to be followed. The possibility of getting caught out here suddenly became very real for me. My heart was pumping so fast that I wouldn’t have been surprised if the others could hear it.

In order to make sure we were a long way from the military we walked pretty much all night. At around midnight we stopped for a brief rest but the cold soon started to seep in and we knew we had to keep moving. The darkness was so all encompassing that I’m glad I wasn’t in charge of navigation.

By four in the morning, the temperature had dropped to about –3 degrees. It’s one of the most surprising things about being in the desert — no matter how hot it is during the day, at night the temperature can drop dramatically. You really have to be prepared for extreme temperature change.

The sun finally started to make its way into the sky at about six in the morning. I was so relieved to be able to see where I was walking and also to take in the beauty of the desert. Ahead in the distance stood a range of mountains and closer still there was a series of table-topped hills. The landscape was mind blowing — golden sand, white limestone all in sharp contrast against a clear blue sky. We decided to dump our gear for a little while and climb to the top of one of the hills. It was such a relief to get my pack off my back and to be able to walk to the top of the hill. The slopes were steep and crumbly so it was pretty hard going but the view made it all worthwhile. And, for once, we felt quite safe because we could have seen anyone coming or any military installations for miles in all directions.

We decided that this would be a good time to rest. It wasn’t perhaps the smartest choice as this was the coolest part of the day but Alvis and I were both in desperate need of sleep. Paul was not happy. He thought that we should carry on while it was still cool. As the photographer on the trip, Paul took this time to go and take some photographs of the surrounding landscape. We had agreed that if he wanted to take photos he would have to do it during our rest stops as we didn’t want to have to stop walking so he could take pictures. If he did take photos while we were walking, he knew that we’d keep going and he’d have to catch up. Being the photographer meant that Paul was carrying 8 kilograms more gear than the rest of us.

On this particular rest break all I wanted to do was sleep. But Paul had other ideas. He thought that I should be helping him carry camera gear and set up shots. I was clearly struggling and my feet were a mess. While the too-small tramping boots had seemed OK in Cairo, my feet and legs had swollen up and they were now causing me all sorts of pain. I spent some time tending to my feet, applying plasters and trying to clean the blisters.

After sorting out my feet I had a few sips of precious water before settling down to sleep. Paul wanted me to go with him on a photography mission but Alvis intervened, ‘Can’t you see she needs to rest? She can’t do that. She’s already at her limits!’ I tried to help him but I couldn’t get up so in the end Paul went off on his own, quietly fuming at having been over-ruled by Alvis.

Three hours later, I awoke to hear Paul putting his gear back in his pack. The sun was absolutely scorching and I knew it was time to get moving again. The combination of the heat, the soft sand and the lack of water made it incredibly tough to keep moving. The guys had got well into their water supplies but I had worked out that if I drank as little as possible during the day when I was hot and drank my ration of water at night, my cells would take up the water more readily instead of sweating it straight out again. During the day I drank only enough to wet my mouth. After a while the torturous thirst all but disappeared by the evening when I would allow myself to drink.

By two o’clock in the afternoon we came across a small limestone formation. It was one of the few things in the desert that threw a shadow. We huddled into the shade that the small shadow offered us and took the chance to rest. Up ahead in the distance we saw a caravan consisting of a woman, six camels and a donkey. It was a magical sight and it made me feel as if I was on a film set. Everything seemed so unreal and beautiful — well, everything except my feet that is. There was nothing beautiful or unreal about the pain they were causing me.

We stayed there for a few hours until the sun started to lose its fierceness. We’d decided to walk on in darkness so as not to lose any more precious water. By the time the sun set completely we’d established a good rhythm and we were all prepared to carry on into the night. Paul decided to go off and take some photographs as the sunset was particularly beautiful. Alvis told him that if he wanted to take photos he would have to catch up with the rest of us as he wasn’t prepared for us all to wait for him. One of the key things about these kinds of trips is that once you get your rhythm or you’re in the zone, you should keep going. It’s really hard to get into that kind of phase and stopping for someone else to do something is really difficult.

Paul went off with his camera, his tripod and a couple of lenses. He expected me to go after him but I wasn’t prepared to stop walking to help him. Alvis, Gunther and I carried on and expected Paul would catch up in a few minutes. Once 10 minutes had passed though I started to worry. The lower the sun got, the more I worried. What if something had happened to Paul? What if he’d fallen? What if he’d got lost? So many questions ran through my mind. With every passing minute the sky got darker. Alvis realised that I was starting to stress but he said nothing. Eventually, he turned round and scanned the way we had come in the hope of spotting Paul. ‘He knows the rules. He’ll catch up,’ was all he said. That was cold comfort to me. ‘But what if he misses us in the dark and loses our tracks?’

Alvis hesitated a moment, looked up ahead and said ‘Damn. We’ll have to camp up here for the night.’ He was angry. Stopping for the whole night because of Paul’s stubbornness would put us all behind. It would mean we’d have to walk further in the sun tomorrow and it would mean that we’d lose precious water rations.

I could tell that if Paul did make it back to us, the tension that had been in the air since his arrival at the airport was going to explode and that would mean big problems for everyone. It seemed whatever happened, it was going to be dramatic. Ten minutes after we’d stopped to make camp, Paul caught us up.

Alvis was furious. ‘We’re staying here for the night. We couldn’t risk losing you and now our schedule is all messed up.’ Paul hated Alvis talking to him like this. And even more he hated that Alvis had doubted his ability for even a moment. ‘I was perfectly capable of catching up,’ he snapped.

‘I didn’t know that,’ replied Alvis. ‘And anyway Lisa was getting very worried.’ I was torn by the whole exchange. Paul was my partner and I knew I should have been backing him up but he’d hardly spoken to me since we met at the airport. Besides, I knew how precarious things were on this trip. He might have had the confidence that he could finish this trip, but I certainly didn’t.

While these two male egos squared off against each other, Gunther said nothing. He was the quiet, easy-going, easy-to-please member of the expedition. He took no sides and went about his business undisturbed. For his calming presence I was truly grateful. I couldn’t imagine what it would have been like if all three of them had got involved in this ‘discussion’.

Paul and Alvis continued arguing for about an hour until Paul turned his attention on to me. Then it all came out. It was my fault that he had got a cold. It was my fault he hadn’t been able to get more water to bring. It was my fault that we hadn’t had a proper brief before we left Cairo.

I was angry at Paul as I knew that the only hope we had of surviving to the end of our journey was to retain some sense of harmony and cooperation within the group. I decided that the only way I was going to survive the days ahead was to shut myself off and to concentrate on what I had to do to get out in one piece.

We stayed in that camp until about three in the morning. The air of tension that hung over us all made it difficult to sleep. When I heard Alvis packing his gear, I knew I had to get up and get moving. My bones were tired. My feet were in a shocking state and you could have cut the air with a knife — not exactly an ideal situation. It was another one of those moments where I longed to be snuggled up in bed at my parents’ house in Oakura.

Thank goodness they didn’t know where I was. Mum would have worried herself sick. She knew that I’d been in the Arabian Desert the previous week but back then phone calls were really expensive. I’d only ring home once every few months — and the cheapest way of communicating was by letter. While I was in Cairo I’d taken the time to write Mum and Dad a letter telling them where I was going and what I was planning to do. I told them I loved them and that if they hadn’t heard from me by the time they got the letter, then something had probably gone wrong. Thankfully, by the time they got the letter, they already knew I was OK!

We started off in the dark again and my eyes longed for sunlight and the warmth of the sun’s first rays. As the day finally started to dawn we found ourselves in the most magical place — a kind of mini Grand Canyon stood before us, only the colours were different. Instead of reds everything was pink and white in the early morning sun. We were all completely blown away by the beauty of the scene. So much so that Alvis even agreed to stop for an hour so we could take it in and Paul could photograph the changing light in the canyon.

Up until this point, we’d managed to cover the required 45 kilometres per day that would see us complete the trip within the allotted 10 days. But ahead of us were the mountains that we’d seen in the distance the day before. There was no obvious path over them — although if there had been we probably wouldn’t have used it because of the risk of being caught. Alvis studied the satellite pictures and decided that the best way forward was to climb up to the nearest plateau and hope for the best. The scale of these pictures was 1:500,000 so everything we did was a gamble — an informed one but a gamble nonetheless.

Slowly we picked our way up the steep slopes. The rock was loose and would give way underfoot. It would have been a hard climb without a huge pack but carrying a load that was two-thirds of my body weight made it extremely difficult and energy sapping. When we got to the top of the first plateau, we were disappointed. From there we could see that instead of being one table-top plateau, what we were going to have to get over was a seemingly unending series of mountains and valleys. We were going to have to continually climb up and down until we came to the other side, which we couldn’t see.

By the time we’d climbed a few of these peaks, the sun really started to burn and I knew that it wasn’t just me suffering. Eventually we took refuge in a spot of shade provided by a rocky outcrop. It wasn’t long, though, before the sun had chased this shadow away and we were left looking for another place to hide from its burning rays.

A couple of hundred metres away was another spot of shade. We just left our gear where it was and headed to the next refuge. There we sat talking about the most important thing in our world — water.

It turned out that Paul and Alvis only had half a litre left of their daily ration. Gunther had slightly more at three quarters of a litre. Me, I still had one and a half litres due to my strict policy of not drinking it in the heat of the day. At that point, it became clear to me that the three of them would not be able to make it through the desert on just two litres a day. Paul was suffering worst because his cold was constantly drying his mouth out. He’d been drinking three litres of water a day and, at that rate, would have to finish the trek in seven days.

Alvis and Gunther were also drinking more than their allotted share, both getting through two and a half litres a day. From this point on, I decided, I’d have to try and survive on one and a half litres a day in case one of the others got in trouble. We’d have to make sure we kept going at a good pace if we were going to get out of there.

Paul suddenly declared that he felt unsafe being separated from his water supply and he headed back to where we’d left our packs.

The rest of us followed him down to where the gear was and agreed to get on our way. The rest of the day was pure frustration. We seemed to be going up and down mountains with no end in sight. No sooner would we summit one but there would be another one in our way. Just before sunset, we found ourselves on the edge of a cliff looking out over yet another valley and another mountain. It was getting dark but we still managed to pick our way down into that valley safely but slowly.

By the time we made camp, it was nine o’clock. We’d been going since 3.30 in the morning and we had only covered 16 kilometres. That was less than half our daily target. We all agreed that tomorrow would be a big day as we needed to make up some of that deficit.

I knew that there was no way I could cover the required 45 or more kilometres that the following day would ask of me if I didn’t lose some weight. And given that I was only about 50 kilos, it was going to be my pack that the weight came out of. Out went half of my food. I’d hardly been able to eat any of it anyway so it wouldn’t be a great loss. This was in the days before freeze-dried meals and high-energy supplements. I jettisoned some stale bread and a block of cheese. All I kept was chocolate and some dried fruit. I would just have to live on scroggin for the next few days.

The next morning, as we reached the top of the very last mountain, we found ourselves in a different world. Here there was sand, sand and more sand. After crossing all those mountains we faced another problem — sandhills. The sand was unbelievably deep and it got in our boots, in our clothes and packs. It was incredibly beautiful but it offered no shade. It was that picture-book view of the Sahara — golden, vast and, well, sandy.

My boots soon filled with sand and it caused real problems with my feet. At one of our rest stops during the day, I took my boots off to check out just how bad things were. My feet were an absolute mess. My right foot felt like it was just one big blister and the pain was excruciating. With every day the blisters were getting worse but there was nothing I could do about it except to carry on.

The first 10 minutes after each rest stop were the worst as I had to really force myself to move. This is one landscape that humans can only survive in if they’re moving. If you stop for too long, your water will run out and then your time is up. The damage to my feet was shocking but not enough to make me lose the will to live. I had to keep moving.

By noon we were all melting. There was no shade anywhere and in the end we gave up searching and just lay down in the sand. The temperature was above 45°C and the cheap sunscreen I’d brought with me was no match for the burning sun. My tongue was sticky and swollen. My lips were cracked and dry. I couldn’t swallow even if I’d wanted to have a drink of water. With our last remaining reserves of energy the four of us managed to dig a hole in the ground to lie in. The sand underneath us was cool and I managed to hang my sleeping mat over the hole to provide us with some much needed shade.

‘One hour,’ said Alvis, ‘and then we’ll search for some more shade.’

The hour was soon up and we got back on our feet and carried on searching for the lithest of shadows to rest in. One hour. Nothing. Two hours. Nothing. Eventually we just collapsed in the sand again. We’d all lost too much moisture and were more exhausted than ever. The heat was unbearable, relentless.

Since the argument two days before, Paul had become more and more withdrawn. He was angry at me for, well, pretty much everything. And he was angry at Alvis for contradicting him in front of me. He was clearly also suffering badly from lack of water. I had neither the energy nor the will to argue with him.

Lying there, collapsed in the sand, things took a surreal turn. Paul asked Alvis if he could speak to him alone. They went off a few metres away and I could tell that the discussion was pretty fiery. When they came back to where Gunther and I were resting, Alvis told us the news that I realised I had almost been expecting. Paul had decided to continue the trip on his own.

A range of emotions washed over me. I was devastated that Paul could bring me out into the desert and then just leave me here. I had to focus on surviving. I was frightened that he wouldn’t make it through alive. Even though I knew that he was more than capable of doing the rest of the trip on his own, I also knew that one wrong step out there could be your last.

More than all of these emotions, I was angry — angry at myself for having decided to come and angry at Paul for leaving me there. I lay in the middle of a burning desert, miles from anywhere with scarcely any provisions and hardly any water. Precious water rolled down my cheeks and I felt what little energy I had drain out of my body. Paul came over and tried to comfort me.

At that moment I knew that my relationship with Paul was over. Never again would he make me feel so bad about myself. He’d dominated my life for long enough. I needed to live my own life. I needed freedom.

Paul returned to where Gunther and Alvis were sitting. I stayed put, took a deep breath and gathered all my strength. For the first time in ages, I had to think for myself. I heard Paul tell Alvis to look after me. With this thought in my mind I felt my determination return.

Paul prepared himself to go and tried to console me. The tears that had come to me moments ago had stopped. I knew I couldn’t afford to cry as it was just a waste of water. Paul’s last words to me were, ‘It’ll be all right’. Then he hugged me and disappeared over the sandhills. Again, I felt like I was in a movie, it was completely surreal. With every step that he took away from me, I separated myself and my energy from him. I hoped he would be all right but I would go on. I wouldn’t waste my precious reserves worrying about him, now I had to take care of myself.

As soon as Paul was out of sight, Alvis turned to me. I could tell he didn’t quite know what to say or do. He was probably thinking he’d now have a hysterical woman on board for the rest of the trip. ‘So, ahhh, are you going to be all right?’ he asked.

A weird mixture of anger, embarrassment, determination and relief combined inside me and I knew that the answer to Alvis’s question was a resounding ‘yes’.

‘You won’t have any problems with me, I promise you.’ He looked relieved and no more was said. The group now down to three, we gathered our bags and moved on. We carried on in companionable silence the rest of the afternoon. When the cool of the evening came, my steps felt suddenly freer. My backpack seemed a little lighter. I began to notice the beauty of the surrounding landscape and I realised that all my other emotions had subsided and the only one left was relief.

As I lay under the thousands of stars of the desert sky that night, I wondered where Paul was and I wondered if he, too, was looking at the stars. I sent him a goodnight kiss and hoped he’d be OK before I drifted off into a surprisingly peaceful sleep.

A few hours later, at three o’clock the alarm went off. It was damned cold and I had to force myself to get up and get going. Those first few minutes after I woke were hard as the realisation of what had happened the previous day came to me. But as hard as that was, I knew I had to block my emotions until I got out of the desert. If we made it out safely, I’d have plenty of time to mourn the end of my relationship with Paul and to work my way through conflicted feelings but right now I couldn’t think about it.

Uncharacteristically, Gunther complained and said he wanted to sleep for another couple of hours. Alvis, who was clearly drained by the events of the previous day, agreed. I was disappointed because I knew that the early morning was the best time to be moving but I realised that the wheels had already nearly fallen off the whole expedition because of me so I was in no position to argue with them. I just climbed back into my sleeping bag and wakefully waited until they were ready to go. It was another four hours before we got moving.

Because we’d had such a late start, Alvis pushed the pace for the rest of the day. By nine the sun was already unbearable and an hour later we had to stop and take a break. Gunther was starting to fall behind and by the time he reached us it was clear the pace was too much for him. Alvis promised to go a bit slower but even then it wasn’t long before the pace was too fast for Gunther again. Gradually, he fell further and further behind and Alvis didn’t let up.

I hung stubbornly in behind him, refusing to let him get away ahead from me. There was no way I was going to hold us back. What I couldn’t work out, though, was where he’d got all his energy from for the day. I didn’t know that during the night, the dehydration had got so much for him that he had drunk his entire day’s ration of water in one go. He was fully recharged and we were flailing in his wake.

Until now, I’d managed to stick to my one and a half litres of water a day. Some days I’d given the extra half litre to Paul but now I didn’t have to worry about doing that anymore and I was beginning to suffer physically from lack of water.

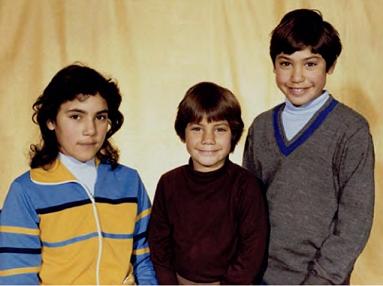

The three musketeers – me, with my brothers Mitchell and Dawson.

Climbing the Grossglockener mountain pass in Austria. It was gorgeous but freezing!

Struggling through a storm in Styria, Austria. Note the trusty good ole PVC raincoat.

Riding on flooded roads in Djerba, Tunisia.

Checking out the view of a salt lake near the Tunisian border with Algeria.

A brief rest stop near Ksar Hallouf in southern Tunisia.

Me following Alvis and Werner on our trek through the Arabian Desert.

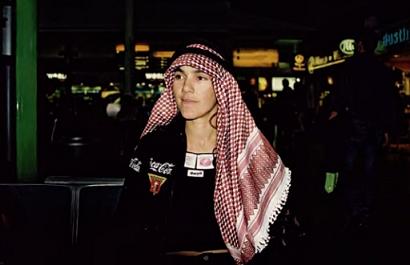

Blending in with the locals in Jordan where I ran the 168 kilometre Desert Cup.

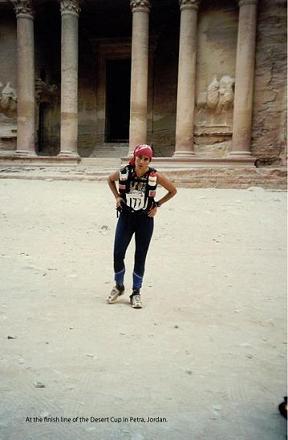

At one of the rest stops for the Marathon des Sables in Morocco.

The landscape in Morocco provides plenty of challenges for desert runners.

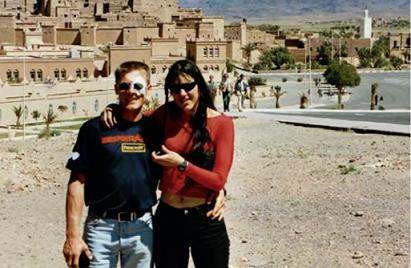

On a mission – me and Gerhard Lusskandl three days into the Marathon des Sables.

At the end of the marathon, Gerhard had to have an operation to remove sand from his cornea.

Whatever troubles I had, Gunther’s were worse. Every time I looked behind me he seemed to be getting further and further away. I started to worry about him. A little while later, Alvis and I found a spot of shade in a shelf on a rock face and we decided to take a break. We’d already covered 30 kilometres that day and were quietly content with our achievement. We’d been resting for about 15 minutes when we realised that Gunther was nowhere to be seen. Alvis left his pack with me and went back to look for him.

I lay there in the shade too tired to move. My feet were causing absolute agony and the skin on my shoulders where the straps from my pack pressed in was numb and bruised. Little did I know then that the feeling in parts of my back wouldn’t return for another six months. My back was in a bad way. My old injuries had been exacerbated — a disc had been pushed out of alignment by the constant weight of my pack. Everything was so out of whack that I couldn’t stretch my arms backwards.

As I lay in that little piece of shade, I drifted off to sleep briefly and dreamed of a huge bottle of Coca-Cola that was standing at the other end of the desert waiting for me. I woke up feeling even thirstier than I had before and decided to drink half a litre of my precious water. I drifted off to sleep again but woke a few minutes later in a blind panic. Alvis and Gunther were still not back. What if they didn’t come back? What if I was alone out here? Could I get myself out? Could I help them if they were in trouble? The consequences of us being separated seemed dire, indeed. Thankfully, before I’d convinced myself that I’d been abandoned I spotted them walking towards me about half a kilometre away.

Alvis was carrying Gunther’s pack and Gunther was walking very slowly behind him. He was extremely dehydrated. Alvis had found him sitting in the sand, disoriented and exhausted. He had lost sight of us and pretty much given up. A long rest was needed. Gunther had to drink and recover so we decided to stay put until four that afternoon before walking another long stage in the cool of the evening.

By now I had recovered a little and took a good look at where we were. It was magic, a gold and white valley with bizarre formations. There were strange, black, perfectly round stones on the ground intermingled with pieces of crystal. I had the strong feeling we were the only humans to have set foot in this place for hundreds, maybe even thousands, of years. I felt privileged and humbled at the same time to be in such a majestic place. The air was completely still and burning hot, nothing moved, nothing lived — no snakes, no scorpions, no insects, no plants, no birds. Nothing could survive in this harsh climate.

Before long though, my thoughts returned to slightly less lofty things. I decided that it was time to get an idea of just how bad my feet really were. I took off my boots and my socks and subjected them to the light of day for the first time in a while. It wasn’t pretty. My toenails were all either black or slowly turning black. My heels were giant blisters and there were various other blistered spots all over the rest of the skin.

I took out my first aid kit and decided to operate. A single blister covered the entire Achilles tendon area on my right heel. I knew that the only thing for it was to drain the blister. For a moment I hesitated before sticking the needle into the blister. It wasn’t pain I was worried about, it was losing all that water from my body. If I could have found a way to store that water after I’d drained the blister, I would have.

In went the needle and the blister was so tight that I managed to squirt myself in the eye when the needle finally broke through all those layers of skin. The blister was so big that it took nearly half an hour to completely drain it. What remained was a floppy bag of overstretched damp skin so I left my foot out in the sun for a while before I plastered it as well as I could with what I had. I knew that whatever I did, that sock wasn’t coming off until we made it to the end of the trek so it’d better be good.

While I was operating on my feet, Gunther was gradually regaining his strength and by late afternoon we were ready to get moving again. Alvis and Gunther had just enough water to last another two days so we had to cover as much territory as we could. I still had 11 litres of water in my pack but they didn’t know that. I just felt that I needed to keep some in reserve in case something did go wrong.

We walked on into the night and even though I couldn’t see, I could sense the landscape changing around us as huge sandhills loomed ahead of us. We managed to weave in and out of the hills only being able to see a couple of metres in front of our noses. Survival was a matter of putting one foot in front of the other. I was mesmerised by the white flicking of Alvis’s heels in front of me, providing me with an orientation point. Suddenly, Alvis’s heels were no longer there for me to follow. He had stepped over a small dip and disappeared and I suddenly realised how easy it would be to lose sight of him altogether. I hurried to catch up and disappeared over the same drop as suddenly as he had.

For the first time, I realised that Gunther wasn’t right behind me. I looked quickly back and there was nothing but darkness. I called out to Alvis asking him to slow down and telling him that we’d lost Gunther again. The pace had been too fast and Gunther had fallen behind. Thankfully he wasn’t too far away, just far enough that we couldn’t see him.

We stopped and waited and I breathed a sigh of relief as I saw his silhouette appear over the ridge behind us. That fright was all it took to make Alvis declare it a day and we set up camp in the sand. But our hopes for a restful night’s sleep were soon dashed.

The evening had been unusually warm and there hadn’t been a breath of wind. As we settled into our sleeping bags a sharp gust of wind took us by surprise. That gust was followed by more and each one got stronger. Minute by minute, the wind increased until it was impossible for us to ignore it. We packed up all our gear and moved to a sheltered spot behind a nearby sandhill.

As soon as we were settled in again the wind turned into a storm, a sandstorm. I huddled down into my sleeping bag and pulled the hood right up over my head, shutting the opening as well as possible. The wind lifted the sand up in bucketfuls and sprayed it on us. Inside my haven it sounded like rain on the roof and I caught myself wondering what it would be like to be buried alive. Now and again I stuck my nose out to get air. The sand was everywhere and in everything, my nose, my ears, my hair, my mouth and all through my sleeping bag and backpack. Nothing was safe. The storm continued into the small hours of the morning and when it finally subsided around 3.30 am. I heard Alvis rustling around outside.

It was time to get up. Another night had passed without sleep. I pulled my aching and tired body out of the sack and got going, feeling very wobbly on my feet. Last night I had hardly drunk anything due to the sudden sandstorm and now my thirst had seemed to disappear and it was so cold I could only drink a little before starting off. It was a warning sign I should have recognised — lack of thirst when you’re already dehydrated is a sign that your nervous system is no longer functioning properly.

Alvis again set a swift pace in the darkness of the early morning. He was determined to put at least 30 kilometres behind us before the sun again beat us into submission. Our goal was to reach the Bawiti Depression by midday. It was a landmark that we could recognise easily on our map and I knew that if we could make it there the worst of the journey would be behind us.

An hour passed and I started to feel very strange, my vision went blurry and my legs felt weak. Suddenly everything went black and I collapsed. I woke up moments later to find myself lying like a turtle on its back unable to get up. The others put me back on my feet. ‘You ok?’

‘Yeah,’ I said, not really knowing what had happened. We continued on in silence. Five minutes later everything went black again and I collapsed. Again, they put me on my feet and we kept going. I was annoyed. ‘What’s the matter with me? Pull yourself together’, I told myself and I tried to concentrate. Again my vision blurred. I kept going but half an hour later I collapsed for a third time. This time I was really disoriented. I obviously needed water quite badly but Alvis didn’t offer to stop and I was either too proud or too confused to ask.

I got back on my feet, gritted my teeth together and carried on. I collapsed a fourth time. By now it was routine for me and automatically I struggled up and carried on. Then finally we were there, before us lay the Bawiti Depression. We had reached the end of the mountain plateau.

What we saw before us was a completely different landscape. The desert was no longer white, but black. We walked to the edge of the cliff and searched for a way down. By now I was extremely disorientated and hallucinating. The rocks were dancing in circles around me then turning into monsters. No matter how hard I tried I could not focus. Alvis discovered a way down, took me by the hand and coaxed me down step by step, ordering me to go on when I hesitated. The way was steep and I felt completely uncoordinated. I focused on his voice and followed his steps.

Finally, we were down. I threw my pack on the ground, ripped it open and tore out the closest water bottle I could find. I reckon that was the most important bottle of water I have ever had. A half a litre disappeared like nothing and I lay down on the ground to recover. My vision was spinning as if I was drunk.

‘Everything OK, Lisa?’ asked Gunther.

‘Yeah, I’ll be back to normal in a tick,’ I answered. I could feel the water filling every dried out cell in my body. I drank a little more and rested. Alvis sat down beside me and encouraged me to drink as much of the extra water I was carrying as I could.

‘There’s an old Bedouin saying,’ he told me. ‘It’s better in your tummy than in your pack.’ Immediately I understood what he meant. It was easy to get obsessed with water rationing. People have died of thirst in the desert with 20 litres of water still in their bags. From now on I would drink my two litres a day because there was always a risk that my nervous system would become too damaged to recover if I kept denying myself water.

We took stock of our position. Things were looking up. It had been a hard couple of days but they had paid off. By the next night, with a bit of luck, we could be out. A feeling of anticipation and elation overcame me and for a moment I almost forgot we still had a long way to go. I hadn’t expected that the sense of nearly having completed the trek would make that afternoon even harder than the ones we’d already survived. Somehow, with the tension and pressure gone, every step seemed to take twice as long.

Late that afternoon Alvis called out a single word — trees. A tiny oasis came into view. There were trees and there were people and that could only mean one thing — water. As if mesmerised, my eyes stayed fixed on that tiny point of hope far off on the horizon. The minutes passed like hours, the trees never came closer and I began to wonder if we had all been hallucinating the same thing. Eventually we arrived and I could touch beautiful green leaves. The colour put me in a trance — life. I picked a leaf. It was from a member of the eucalyptus family and it smelt heavenly.

Alvis tried to take a GPS bearing but the unit wouldn’t work. It was probably because we were still in a military controlled zone and the satellites were being jammed by the soldiers. We walked into the oasis in search of water and found two men working in a garden where water ran through in canals to irrigate the plants. Alvis greeted them. Completely taken by surprise, they greeted us warmly.

We must have looked a sight because they immediately offered us water. We gratefully accepted and followed them to a spring where we were offered a cup to drink from. In turn we each drank our fill from the lukewarm water that gurgled out of the earth. None of us managed more than a litre. Our stomachs simply couldn’t hold any more.

We thanked our hosts and took our leave wanting to disappear as quickly as possible. We had to get out of sight again before there could be any trouble — for them or for us. Their hospitality was very touching and I’m still surprised that they weren’t suspicious of us or curious as to why we had turned up out of the desert.

The oasis was blocked on the other side with dried out salt lakes and swamps. After making our way through the driest of landscapes for the last few days we found ourselves trudging through soggy wet mud with a thick salt crust on top. Alvis charged right in, in a hurry to get out, but the ground got soggier with each step until our great leader got stuck in the mud.

I was not far behind him, but being lighter I didn’t sink in so far. He struggled to free himself but by the time he managed to free one foot the other was completely trapped. I couldn’t help it and I started to laugh. This annoyed Alvis no end and made him fight harder to get out, which caused him to fall over. Gunther and I completely lost all control and laughed ourselves stupid at the sight of Alvis flailing in this swamp. That just made him even more angry. ‘We have to disappear, this is no laughing matter.’

He was right, of course. We were dangerously close to civilisation and where there were people there were bound to be soldiers. Biting my lip, I offered Alvis a hand and step for step we made it back on to dry land. What a sight, the ‘great master’ covered in mud in the middle of the desert. Gunther and I looked at each other; we didn’t dare make a noise. We hopped back into line and marched on in silence for a long while.

The landscape here was a stark contrast to what we had been walking in. The sand was covered by black rocks and black volcano-shaped mountains were everywhere. I was astounded and fascinated with the beauty of the place, but the stones were incredibly uncomfortable on my tender feet.

We walked until late in the evening, motivated by the thought this could be our last night in the desert. Like a greyhound with a rabbit before its eyes, I hurtled forward with the vision of a chilled bottle of Coca-Cola in my mind. We finished that day with just 45 kilometres left to cover before making it to Bahariya and safety. We knew we would be out the next day and that helped me to sleep better.

The final day of our desert adventure started at 6 am. None of us had any problems getting motivated to get up and get going early that morning. The end of the trek was getting closer with every step we took. As we walked, we talked about what we would do once we got out and got home. Even though my return home was shrouded with uncertainty, the atmosphere was relaxed and although we still had a long way to go we didn’t care.

My backpack felt as light as a feather. My legs felt strong and fit. The kilometres ticked by without me even noticing. Even my feet didn’t seem to hurt that much. I wondered at what a powerful influence the psyche has over the body. It was amazing to me that when I had a positive attitude and was able to focus and find an inner rhythm, anything was possible. But the opposite was also true. When I felt negative, undecided or distracted, even getting out of bed could become too much of an effort. This discovery has held me in good stead time and time again since I first noticed it out there in the Libyan Desert.

The only thing that mattered now was getting to Bahariya and the end and this goal energised me beyond belief. As we got closer to the oasis town, my thoughts began to stray towards Paul for the first time since the night he left me in the desert. What would happen with us? As soon as this thought popped into my mind I lost my rhythm and felt like I didn’t want to reach the end. I didn’t want to return to the complications of everyday life. I didn’t want to have to deal with whatever fallout was awaiting me when I got back to civilisation. More than that, I didn’t want to see cars and streets. I didn’t want to hear music and people. I wanted to remain here in the untouched wilderness, in this beautiful, serene and deadly place.

Towards evening we finally saw the lights of the oasis on the horizon. I felt sad. The Coca-Cola bottle that I had fantasised about for so long had lost its magic. This discontentedness confused me. When I was on tour, be it in the mountains, the desert or the forest, I always longed for the comforts of home. Then once I got home I knew I’d long for the freedom to move, to be going somewhere, for the nature, the beauty and the satisfaction of being on tour.

The lights of Bahariya oasis came closer and closer. It was night time as we approached. Already rubbish and other signs of humanity were starting to appear. As we neared the oasis the three of us fell silent. We couldn’t risk being seen and caught by the military who have a control point in every oasis.

Standing just outside the oasis, excited and elated, we congratulated each other. We had done it. But our celebrations were premature. None of us had noticed we were standing only 50 metres away from a military look-out tower. We quickly ducked down behind a wall. ‘What do we do now?’ whispered Gunther.

‘We’ll have to find a way through the wall somewhere and into the village,’ came Alvis’s reply.

While the two of them discussed possibilities, I popped the last lolly I had into my mouth and sucked on it. I had saved it until the end and here we were.

We crept along the boundary wall looking for a way in. Without finding anything we realised that we would have to pass right under the tower. We managed to sneak by right under the noses of some Egyptian soldiers and found a hole in the wall.

The three of us climbed through the hole and into a paddock where a surprised looking donkey was standing. After that, we scaled another couple of walls and found ourselves inside the village amongst the houses. We were safe.

The locals were shocked to see us but once again, the wonderful sense of Egyptian hospitality came to the rescue. A few of the local men guided us to the centre of this dusty little town and a building with a sign outside. On that sign was one of the most magical words of all: HOTEL.

The three of us walked straight in and checked in. Our room was very simple and slightly grubby but it was absolute luxury. We had really made it. We had traversed the Libyan Desert and lived to tell the tale. I lay on the bed feeling exhilarated and relieved.

The danger of the last hour now struck me and I shuddered. But it wasn’t long before that fear subsided and I managed to focus my thoughts on another all important goal — that long-awaited bottle of Coca-Cola. Together, Alvis, Gunther and I marched through the town as if we owned it. We were proud and happy. Despite all the difficulties we had encountered we knew we made a good team. We found a little shack with a sign outside saying ‘Café’.

‘Six Coca-Colas please,’ Alvis ordered for us, ‘and something to eat.’ As the man handed us our two bottles of Coke each we looked at each other with pride.

‘Cheers comrades. We did it!’ said Alvis with a smile that reached from one ear to the other.

That first drink almost brought tears to my eyes and I savoured every drop as it passed down my parched throat. Already the dinner was being served. A type of ragout with a big piece of meat in it, rice, flat bread and veges. It was a simple meal but it was heavenly. After a couple of mouthfuls I was full — my stomach had shrunk from eating very little over the previous week.

We sat back enjoying a few more bottles of Coke and discussed our plans for the next few days. Our flight from Cairo back to Vienna didn’t leave for another week. At about this time, I started to worry about Paul again. Had he made it out? Was he safe? I hoped to have an answer soon.

Later that night, we returned to our hotel and as I lay on the bed I felt a sense of relief. I could finally relax and let my body begin to heal itself. But with that relief came a tiredness and an emptiness I couldn’t understand. The goal that had obsessed me, pressured me and driven me was no longer there. I had a strong, almost unbeatable, desire to turn around and walk back out into the desert.

Being in the desert I had been able to turn my back on the pressures and concerns of daily life. I hadn’t had to worry about money, work, society or expectations. Even though the experience had been brutal at times, my life had been reduced to the absolute necessities. All I had to focus on was survival and everything else had become peripheral.

I was scared to return to a world where my senses could be dulled again by a comfortable lifestyle. I dreaded being bombarded again with a thousand messages every day that were utterly meaningless to me. But there was no choice, I was not born a Bedouin nomad in the Sahara but as a Maori woman in New Zealand and I only knew our world, society and culture. I could only live in these circumstances a short time. It was not my home, or what I knew. With these thoughts I drifted into a deep sleep.

Early the next morning, I left the others sleeping and went to change some money at the hotel reception. As I reached into my purse to get the money out, I felt someone tap me on the shoulder. I turned around to see Paul standing there.

‘Oh, um, hi. You’re out,’ I said. His presence there had surprised me and for a moment nothing more passed my lips. It was clear that we both felt awkward. I wanted to hug him. I was relieved he was OK, but this wasn’t the right place for the conversation we needed to have. So, I followed him back to his room — he was in the same hotel. We exchanged small talk about what we had done and when we had got out. When I started to talk about our plans for the next few days, his face turned cold and his manner tense. I felt the pressure building and I couldn’t wait any more.

‘And what is with us?’ I asked. After hours of discussing, arguing, crying and tension I finally got an answer to my question. We agreed we would part after an intense, exciting, turbulent and adventurous relationship that had been the centre of my life. We were both sad and hurt.

Paul pretended to be hard and cold and I just gave up, I couldn’t fight any more. For months our relationship had been rocky and time and time again we had been on the brink of breaking up but something had always kept us together. This time it was too much for me.

I needed to stay true to the decisions that I’d made out there in the desert the night Paul left me. The desert had given me the right to take my life back under control and had empowered me to let go despite the hurt. We would just have to get through the next few days here together until our flight left. Once we got back to Vienna I would pack my things together and leave for home as soon as possible.

Later that day Alvis and Gunther joined us for a meal. The tension in the air was modified only by attempts to be polite to one another. We were going to be stuck together for the next seven days, so we had to make the best of it. After all we were in an exotic location on holiday and there were many things to see and do. We decided to spend four days in the oasis exploring before returning to Cairo to visit the usual tourist attractions.

Alvis had been in this oasis twenty years before and he had met a local man named Abdul Wahab. On the day he had met Abdul it had rained for the first time in over 20 years. Abdul had found that remarkable and he had told Alvis that he must be very special and that he would not forget him. Alvis wanted to find Abdul again. We asked after him everywhere and were eventually led through the backstreets of the oasis to his house. Abdul was delighted to see Alvis and immediately offered us a tour of the village. A quiet gentle man with a wife and six children aged between eight and twenty. He was a watchmaker and he made a good living from his work.

On our tour he took us through the backstreets and we explored in detail the bubbling hot water springs that provided water for the people and the date palm plantation of more than 100,000 trees that provided the people with food and a green habitat to live in.

At the edge of the oasis were a number of salt lakes surrounded by swamps. Life blossomed here, with insects, birds and animals in stark contrast to the lifelessness only a few kilometres away. I marvelled at the power of water and at the delicate balance of such an ecosystem. If the water ran out life in the oasis would be over.

Abdul led us through a maze of gardens hidden under the date palms and explained how each family owned a small area where they grew their food. Throughout the plantation ran a maze of irrigation canals providing water for the trees and plants. The air in this jungle was moist and hot and as we wandered through I felt weak and unwell. The dryness of the desert air had made the heat bearable but here the air felt heavy to me.

Our tour led further on to brick-making sites where bricks were fired for the building of houses. I had taken over the job as photographer from Paul. Everything was photographed to document life in the oasis. With the advantage of having a local to guide us I was able to photograph the cheeky children who followed us, the old men in their traditional dress and the otherwise camera-shy Islamic women of Abdul’s family to my heart’s content. It was a photographer’s dream.

In the afternoon Abdul took us back to his house where I was left in the kitchen with his wife and children while the men drank tea in the main room of the simple dirt-floored house. The children were excited by my presence and by the camera. I was dragged everywhere to photograph everything from the neighbours’ houses and the school, to every child in the neighbourhood. Abdul’s wife, a short happy lady with lovely smiling eyes invited me to drink tea with her. With no verbal communication Abdul’s wife and children tried to make me feel welcome. We sat on the floor in the kitchen and attempted to communicate with each other.

After a while she took me by the hand and led me outside taking with her on the way two live chickens sitting in a basket by the kitchen door. With great pride she took the two chickens and slaughtered them in front of me, slitting their throats before throwing them on the ground to bleed to death. I was shocked at their sudden and brutal death and wondered what was happening. With the help of sign language I managed to understand we were invited to dinner and that she would like me to help pluck and cook the chickens, something that she understood to be a privilege and a gesture of friendship.

Being a supermarket dependent Westerner I had never plucked a dead chicken and had no desire whatsoever to do so now but I didn’t want to offend her. What to do? I smiled and followed her back into the kitchen with the half dead chickens still kicking on a plate. Suddenly Paul was standing in the doorway. ‘How is it going in here?’ he asked.

‘Ah thank goodness you are here, you have to rescue me, she wants me to pluck these chickens,’ I said.

‘Ha, just your cup of tea! OK, I want to go back to the hotel anyway. I’ll go and tell Alvis,’ he said. Five minutes later all three appeared to rescue me. We returned to the hotel to rest and clean up before dinner.

At dinner, my stomach was churning at the thought of having to devour the two helpless, sweet chickens. I didn’t want to appear ungrateful. For the Wahab family this was a great sacrifice, they had killed their only chickens in order to prepare a feast for us, the honoured guests. Their generosity certainly touched me.

That evening I was given honoured status in that I was allowed to eat with the men. Abdul and the four of us were seated at the table while his wife and children served us before returning to the kitchen where they were to eat. A feast had been prepared and I wondered how on earth they had managed to get all the ingredients. The meal was superb and very generous with homemade bread that was stored, dried and then soaked in water before being served. We dipped our bread into the different sauces and dishes. When we had all been overfed Abdul invited us to go bathing in the hot pools, a ritual usually reserved only for men, but he assured me that in the darkness and with the appropriate clothing, I could join them.

I wasn’t sure at all but Alvis gave me the OK and I was dying to sit in the hot water so I joined them. Perhaps, I thought, the other men won’t notice I am a woman in the darkness. The water was hot, unbelievably hot, so hot that none of us managed to get right in. Inch by inch we let ourselves slowly submerge up to the hips, while the Arab men jumped right in and played in the water.

As I sat on the edge of the pool I felt the stares of the other men and started to feel uncomfortable. Perhaps it hadn’t been a good idea after all so I decided to hop out of the water. In the darkness I tried discreetly to get dressed. Suddenly, I was surrounded by three young men who made conversation with me in English. Politely I answered their questions. ‘Are you married?’ they asked.

‘Yes,’ I answered.

‘Where is your husband?’

‘Over there,’ I pointed to Paul. Here it was a good idea to say you were married whether you were or not.

‘Does he do karate?’ With this question I started to feel very uneasy. One of the men touched my hair, another grabbed my breast. I politely pulled away and called to Paul and Alvis who came over and rescued me discreetly accompanying me back to the pools.

Abdul led us back home unaware of the incident and I walked in between Paul and Alvis kicking myself for being so naïve and thanking my lucky stars I had been born in the Western world. The lack of freedom for women in this part of the world would, for me, be unbearable. Our gracious host Abdul and his family bid us goodnight and we thanked them for their hospitality before taking our leave for the night.

The next day Paul and I explored every nook and cranny of the oasis. We tried to be civil to each other but it was clear that neither of us wanted to be there any longer than we had to. We had things to settle at home and the waiting brought only frustration and stress. I wished this whole unpleasant break-up was already over. My future was uncertain. Paul and I had made all our plans together. Our attitude to life and the way we wanted to live was the same.

Now everything was turned on its head and I felt tired. My backpack had been light in comparison to the load I was now carrying. The energy and fight that had brought me through the desert had left me and the desert itself had taken its toll on my resources. The minor problems like blisters and fallen out toe nails would soon heal without permanent scars but the dehydration had done more damage than I realised.

With still four days to go until our flight back to Vienna we returned to Cairo. Another sandstorm accompanied our departure and the air in the bus was filled with a fine dust that made breathing uncomfortable. I peered out the window as we left the oasis, a thousand memories rushing through my mind. It felt good to be back on the road again.

That afternoon we arrived in Cairo amidst the continuing sandstorm. The city seemed even more chaotic than ever with its wind-chased residents darting everywhere. After a very long taxi ride we found our way back to our hotel, collected the things we had left at reception and went out to explore the streets. As the expedition was over and we hadn’t eaten much all day we decided to risk a bout of belly problems and ate in a street café where the locals ate. Falafels and bread followed by fresh pressed orange juice all at the cost of a few cents.

The next day we hoped to visit the famous pyramids but instead we spent the time changing our flight tickets in order to get home earlier then fighting our way through a huge bazaar searching for an orange juice press. We then went and visited the centre of Islamic life in Cairo, the Muslim University. Being a woman I couldn’t go inside so instead I sat at the door with my shoes off and a scarf over my head next to an old man with no teeth and a smiley face. While I was waiting there I started to feel decidedly unwell and was glad for a moments’ rest.

The next day as I sat in the plane on the runway at Cairo airport and waited four hours until take-off, I felt the first cramps of a bout of dysentery, which was about to make the trip home hellish. It seemed an almost fitting end to such a turbulent adventure.

How to deal with blisters

Blisters can be horrendous and they can sometimes cause blood poisoning, but they can generally be worked through though. Yes, you’re walking on an open wound but once you start moving and you’ve been going for 10 to 15 minutes the pain of a blister will lessen. Once you stop and rest and then start again — that’s when the blisters are excruciating. Like most pain symptoms they’re always worse when you’ve stopped and are getting started again. Once the body starts to warm up again and loosens up, you should be fine.

I’ve had some horrendous blisters in my time and there are varying theories on how you should deal with them when you’re running. Here’s what I do:

Pop the blister, drain it as much as I can and gently smooth the skin back down flat.

Pop the blister, drain it as much as I can and gently smooth the skin back down flat.

Next, put some drying powder on it and tape it back up. When I’m in the desert, to avoid more sand getting in my blisters, I tend to treat them then tape them up and leave them. I try not to touch them then until I’ve finished the race to avoid reopening them.

Next, put some drying powder on it and tape it back up. When I’m in the desert, to avoid more sand getting in my blisters, I tend to treat them then tape them up and leave them. I try not to touch them then until I’ve finished the race to avoid reopening them.

I wear Injinji socks. They’ve got toes in them and they’re fantastic to stop the rubbing between your toes and they draw the moisture away from your feet.

I wear Injinji socks. They’ve got toes in them and they’re fantastic to stop the rubbing between your toes and they draw the moisture away from your feet.

The real key with blisters is keeping them clean. If you don’t then you’re risking blood poisoning.

The real key with blisters is keeping them clean. If you don’t then you’re risking blood poisoning.

Trekking in the desert

In a desert environment, with temperatures over 40°C, it is completely inadvisable to drink only two litres of water a day. Chocolate and nuts aren’t ideal food for a desert trek. Borrowing boots from someone else isn’t smart. Kids — don’t try this at home!

Packing for an expedition

Work out how much water you need every day and make sure you take it. A GPS system is great but they use heaps of battery power. You’ll be carrying those batteries and it’ll add plenty to the weight in your backpack. Always take a compass as a back-up.