2

An Integrative Approach to Cancer Prevention

HEATHER GREENLEE

KEY CONCEPTS

An individual’s risk of developing cancer is determined in part by genetic predisposition and lifetime exposures. Information about these factors can be used to recommend an appropriate screening schedule.

An individual’s risk of developing cancer is determined in part by genetic predisposition and lifetime exposures. Information about these factors can be used to recommend an appropriate screening schedule.

Conventional approaches to cancer prevention include behavioral modifications (such as dietary changes and physical activity), biological agents (such as antioxidants, multivitamins, minerals, hormone modulators, and anti-inflammatory agents), surgery, and vaccinations.

Conventional approaches to cancer prevention include behavioral modifications (such as dietary changes and physical activity), biological agents (such as antioxidants, multivitamins, minerals, hormone modulators, and anti-inflammatory agents), surgery, and vaccinations.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches to cancer prevention include special diets, botanicals (for various properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune modulating, hormone modulating, and adaptogenic effects, and the induction of biotransformation enzymes), vitamins and minerals, other dietary supplements, mind-body therapies, and energy therapies.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches to cancer prevention include special diets, botanicals (for various properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune modulating, hormone modulating, and adaptogenic effects, and the induction of biotransformation enzymes), vitamins and minerals, other dietary supplements, mind-body therapies, and energy therapies.

Non-Western systems of healing such as Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Tibetan medicine, and Native American medicine offer their own perspectives on what causes cancer and what can be done to prevent cancer.

Non-Western systems of healing such as Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Tibetan medicine, and Native American medicine offer their own perspectives on what causes cancer and what can be done to prevent cancer.

An integrative approach to cancer prevention encourages individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices, use appropriate cancer screening technologies, and maintain a sense of wellness and balance.

An integrative approach to cancer prevention encourages individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices, use appropriate cancer screening technologies, and maintain a sense of wellness and balance.

Disease prevention is generally viewed as encompassing three levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary. The goal of primary prevention is to reduce the risk of developing the disease. Primary cancer prevention measures include the use of chemopreventive agents, the avoidance of exposure to environmental carcinogens, and surgical removal of susceptible organs (e.g., prophylactic mastectomy) [1]. Secondary prevention involves screening and early detection methods, used among asymptomatic individuals to identify abnormal tissue changes or precancerous lesions before they become cancerous or detect them at an early stage when treatment is most likely to lead to a cure [1]. Tertiary prevention, often referred to as cancer control, involves preventing existing cancer from spreading, preventing recurrence, preventing second primary cancers, and preventing other cancer-related complications. Tertiary prevention includes a variety of aspects of patient care, including interventions to improve quality as well as duration of life, adjuvant therapies, surgical intervention and palliative care [1]. This chapter will focus on primary cancer prevention and will discuss what people without a cancer diagnosis can do to reduce the risk of developing cancer.

Current conventional cancer prevention approaches begin with risk assessment based on age, gender, genetics, personal and family medical history, and occupational and lifestyle exposures. Appropriate interventions are recommended based on the determination of individual risk. Everyone can benefit from a healthful diet and physical activity. Individuals at higher-than-average risk may want to consider pharmacological chemoprevention, surgery to remove the susceptible organ, and vaccinations. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches include largely biologic therapies and behavioral modifications such as dietary modifications, botanicals (herbs), vitamins and minerals, other dietary supplements, mind-body therapies, energy medicine, and non-Western systems of healing.

Until recently, the mere concept of primary prevention of cancer was considered somewhat unconventional because there was little evidence to support the concept that carcinogenesis [1] could be reversed or halted, or that people could change their habits to prevent cancer. However, in the past two decades, clinical trials have shown both that cancer can be prevented (or postponed) and that people can modify their diet or stop smoking to reduce their cancer risk. The tamoxifen trial proved that a drug could reduce the risk of developing breast cancer among women at higher than average risk [2], and a low-fat diet was shown to reduce the likelihood of breast cancer recurrence [3]. These and other trials proved the principle that cancer can be prevented and provided support for the idea of a continuum between cancer prevention and cancer treatment.

Prevention and Risk

Some individuals without specific known risk factors for cancer are more focused on preventing cancer than on preventing other conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, for which their actual risk may be higher, or on maintaining their health and ability to enjoy life. The good news is that maintaining a heart-healthy lifestyle may also prevent cancer. For example, the impact of not smoking is greater on cardiovascular disease risk than on cancer risk.

Cancer prevention trials are generally conducted among individuals who are known to be at higher than average risk of developing cancer. The higher the cancer risk among the study subjects, the less person-time and cost required to observe the effects of the intervention, if any, and the greater the justification for exposing subjects to an intervention that may have adverse side effects. The risk reduction associated with a preventive intervention may not compensate for its effects on quality of life or its economic costs. For example, among women with a strong family history of breast cancer, prophylactic mastectomy has been shown to reduce breast cancer risk by 90% [4], and tamoxifen reduces risk by 50% [2]. But relatively few women, even with very high risk, have taken advantage of these options. Some are looking to CAM for less invasive and gentler alternatives.

Treatments that begin as CAM can become conventional, depending on research results and the ways in which both the therapy and the context for its use evolve. For example, green tea is now being studied for its chemopreventive potential [5]. Historically in many Asian cultures, green tea was an infusion prepared and sipped during important social interactions and considered part of the good life. Now, it is being studied as a pill or capsule that is swallowed quickly to prevent a disease. In the end, what we want to know is not whether a therapy is considered CAM or conventional but whether it is effective in preventing cancer.

This chapter discusses an integrated approach to cancer risk assessment and prevention therapeutics and provides an overview of conventional and CAM approaches commonly used in the United States.

Assessing Cancer Risk

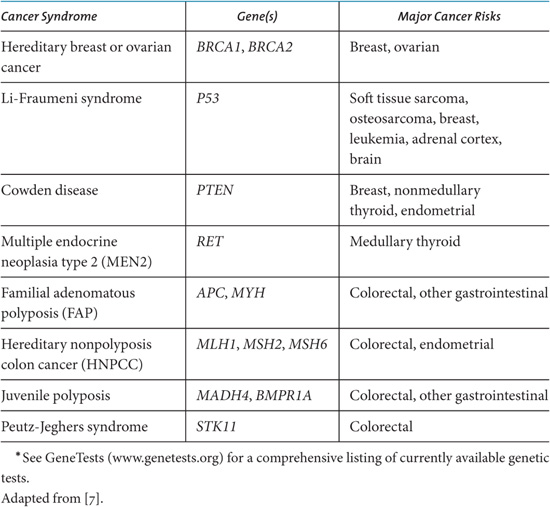

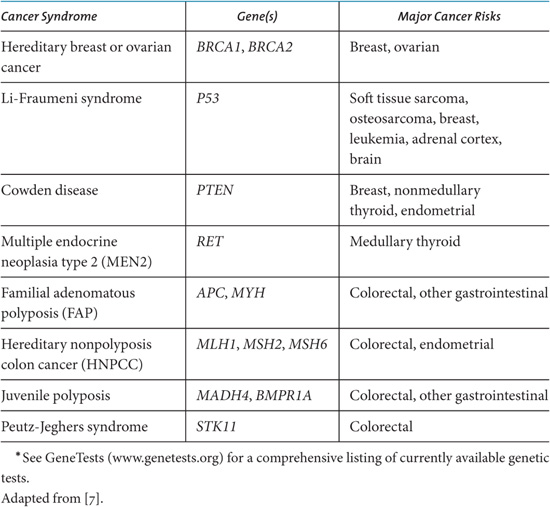

A person’s risk of developing cancer is based on several factors, including family medical history, genetic predisposition, and lifetime exposures. If a physician learns that a patient has a family history of cancer suggestive of genetic high risk, the patient may be referred to a genetic counselor who takes a detailed personal and family history and then makes a determination as to whether the individual should undergo DNA testing. Table 2.1 lists some mutations associated with cancer risk. Based on the risk assessment and possible genetic test results, individuals and their physicians can make joint decisions on what, if any, actions to take, including lifestyle modifications, increased screening, chemoprevention, and/or surgery [6]. The US National Cancer Institute (NCI) has regularly updated websites that explain the concept of risk to the public (http://understandingrisk.cancer.gov) and describe what is currently known about cancer causes and risk factors (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/prevention-genetics-causes/causes).

New technologies are being developed and tested to provide biological assessments of cancer risk, including genetic profiles that determine how the body metabolizes endogenous and exogenous substances, that is, metabolomics and proteomics; thermography, which may detect areas of a breast that have increased metabolism; cytology sampling, such as ductal lavage and mammary aspiration for breast cancer; and blood-based biomarkers such as nuclear matrix proteins. The acceptance and uptake of new technologies for assessing cancer risk is generally based on results from clinical trial data, though there are no formal guidelines or governing bodies that regulate this area.

Table 2.1. Examples of Genetic Testing for Inherited Cancer Syndromes.*

Some clinicians and laboratories offer alternative laboratory tests and in-office procedures that provide nonvalidated assessments of cancer risk. These may include urine analyses, blood analyses, genetic analyses, energy scans, electromagnetic scans, and so on. Many of these methods are based on epidemiolo gical studies and/or theoretical assumptions, as opposed to clinical trials, and have not been validated as diagnostic of cancer risk. The tests are often co-marketed with neutraceutical products that will “correct” whatever imbalance is detected. Most of these tests and products have not been evaluated in cancer prevention clinical trials and their claims should be carefully scrutinized.

Cancer Prevention Modalities

Both conventional and CAM therapeutic modalities for primary cancer prevention involve lifestyle modifications, such as dietary changes, physical activity, behavioral modifications, and biological agents that may prevent or halt carcinogenesis. When considering any approach to cancer prevention, whether it be conventional, CAM, or integrative, it is important to determine the magnitude of expected benefit while accounting for safety, cost, and likelihood of adherence. Some prevention approaches are targeted to the population level, such as strengthening antismoking laws to prevent lung cancer. Other approaches are targeted to an individual, and have more predictably large effects, such as prophylactic mastectomy in a woman with a BRCA1 mutation. In addition, some cancer prevention strategies will also decrease the risk of other diseases, for example, increasing physical activity also decreases risk of cardiovascular disease.

It is important to acknowledge that it is often difficult to convince people to participate in cancer prevention interventions, whether conventional or CAM. Just because a conventional cancer prevention method is espoused by the conventional medical community, it is not necessarily widely in use or widely accepted by the general population. One of the biggest barriers to cancer prevention is convincing people that it is possible and beneficial to make changes in their lives, for example, quitting smoking. Sometimes, CAM approaches may be more appealing to individuals who are unwilling to tolerate some of the side effects of conventional therapies or who find that conventional therapies do not fit within their own personal or cultural system of beliefs and preferences.

CONVENTIONAL CANCER PREVENTION MODALITIES

Conventional recommendations on what people can do for cancer prevention are usually based on epidemiological and clinical trial evidence. These include dietary modifications, physical activity, behavioral modifications, biological agents, surgery, and vaccinations. Some of these cancer prevention approaches are believed to be important and safe enough to disseminate via public health messages and to make changes in public health policy, particularly pertaining to smoking cessation. Public smoking restrictions and tobacco taxation have both resulted in decreased smoking rates, even among youths [8]. Federal legislation has been proposed to reduce low-nutrition foods in public schools [9]. Grocery produce shoppers frequently see the “5 a day” message to encourage fruit and vegetable consumption [10]. New urban planning efforts and employer subsidies for health club memberships are beginning to promote increased opportunities for physical activity [11].

Diet and Physical Activity

It is generally accepted that high intake of fruits and vegetables is beneficial for cancer prevention [12]. The benefits are likely be due to the high concentrations of antioxidants, other phytonutrients, and fiber [12].

Cruciferous vegetables are one family of edible plants that may play a significant role in cancer prevention [13]. High intake of cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, kale, bok choy, Brussels sprouts, radish, and various mustards has been associated with decreased cancer risk. Crucifers have high content of glucosinolates and their hydrolysis products, isothiocyanates, protect against carcinogenesis. Crucifers also contain flavonoids, polyphenols, vitamins, fiber and pigments that may have anticancer activities. The most important chemoprevention mechanisms may be that crucifers inhibit phase I enzymes, for example, cytochrome P450s, which can activate carcinogen metabolites and they induce phase II enzymes, for example, glutathione transferase enzymes, which enhance carcinogen detoxification [13].

Epidemiological data has also suggested that a low-fat diet can help prevent cancer [12]; however, clinical trial data were lacking to support this. The recently published results from the WINS study showed that a low-fat diet was associated with a decreased breast cancer recurrence rate among women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancers [3]. Future clinical trials need to elucidate whether the type of fats consumed contributes to cancer risk.

It is generally accepted that maintaining a healthy body weight, which is defined as a body mass index (BMI) between 18 and 25 kg/m2, can help prevent cancer. The mechanism here has not been fully elucidated but it is hypothesized that some of the endogenous hormones produced with increased body fat increase cancer risk. Maintaining a healthy body weight is best achieved by eating a balanced diet and engaging in regular physical activity.

There is also evidence to suggest that alcohol increases the risk of some cancers [12].

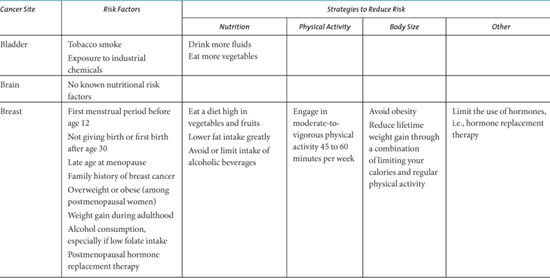

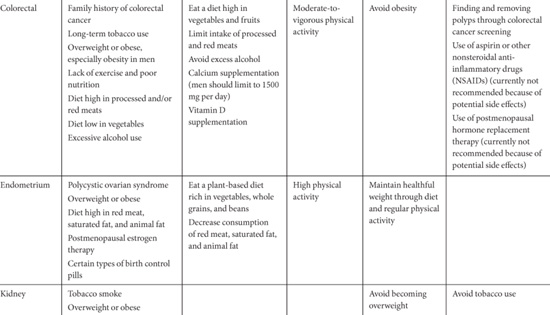

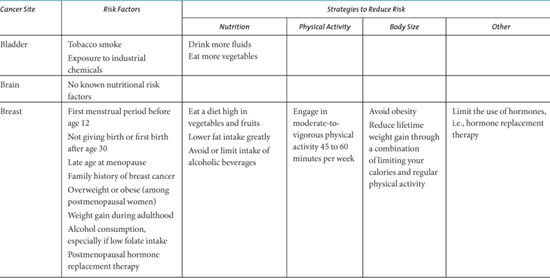

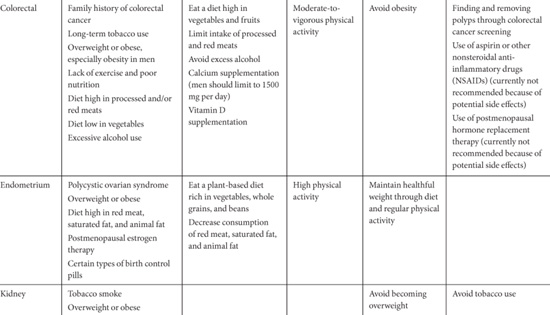

The American Institute of Cancer Research offers the following general diet and health guidelines [12]: (1) be as lean as possible within the normal range of body weight; (2) be physically active as part of everyday life; (3) limit consumption of energy-dense foods; avoid sugary drink; (4) eat mostly foods of plant origin; (5) limit intake of red meat and avoid processed meats; (6) limit alcoholic drinks; (7) limit consumption of salt; avoid mouldy cereals (grains) or pulse (legumes); (8) aim to meet nutritional needs through diet alone; (9) mothers to breastfeed; children to be breastfed; (10) cancer survivors to follow the recommendations for cancer prevention. See Table 2.2 for a cancer-site specific summary of risk factors and dietary and physical activity recommendations by the American Cancer Society.

Behavioral Modifications

A number of behavioral modifications beyond dietary and physical activity have been associated with decreased cancer risk. These include preventing tobacco use, ceasing tobacco use, decreasing sun exposure, and decreasing use of exogenous hormone therapy. Tobacco use, including smoking and chewing tobacco, has been strongly associated with cancers of the lung, lower urinary tract, upper aero-digestive tract, pancreas, stomach, liver, kidney, and uterine cervix, and causing myeloid leukemia [14]. Despite the fact that decreasing tobacco consumption by preventing initiation and promoting cessation would lead to preventing the largest numbers of cancers, this has been difficult to achieve and smoking rates are growing globally [15,16]. Regular sun exposure, especially at an early age, is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer. The regular use of sunblock and using sun-protective clothing have been associated with decreased risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer [17]. The recently reported population level decrease in breast cancer incidence in 2003 is possibly associated with the decreased use of hormone replacement therapy after the results from the Women’s Health Initiative were reported in 2002 [18]; however, this may also be due to a decrease in screening mammography. See Table 2.2 for a summary of behavior modification recommendations provided by the American Cancer Society.

Table 2.2. Cancer Site-Specific Risk Factors and Recommendations to Reduce Risk.

Biologically Based Agents

Biological chemoprevention agents that can be taken as a drug in pill form are appealing because they are less laborious to administer and more easily standardized than lifestyle changes. Chemopreventive agents include vitamins, minerals, naturally occurring phytochemicals, and synthetic compounds. Currently, the most promising agents include biologicals that have antioxidant, hormone-modulating, or anti-inflammatory properties. Botanical agents have been shown to affect numerous molecular targets for chemoprevention, including protein kinases, antiapoptotic proteins, apoptotic proteins, growth factor pathways, transcription factors, cell cycle proteins, cell adhesion molecules, metastases, DNA methylation, and angiogenesis [21].

This is an active area of research involving pharmacological, biological, and nutritional interventions to prevent, reverse, or delay carcinogenesis. Currently, the only FDA-approved agents for cancer prevention are tamoxifen and raloxifene for breast cancer prevention among high-risk women [2,22]. However, the Division of Cancer Prevention of the US National Cancer Institute is actively pursuing new and novel compounds for cancer prevention. Some of these agents include NSAIDs, curcumin, indole-3-carbinol/DIM, deguelin, green tea (Polyphenon E), isoflavones in soy, lycopene, and resveratrol [5]. Many of these agents are used by CAM practitioners and some are discussed below under CAM therapies.

ANTIOXIDANTS Antioxidants include compounds such as vitamin E (α- toco -pherol), vitamin C (ascorbic acid), β-carotene, selenium, and zinc. Many of these agents are found in foods and can also be taken as dietary supplements. Exogenous antioxidants ingested via foods or dietary supplements can quench procarcinogenic reactive oxygen species (ROS) and may halt carcinogenesis [23,24]. Many different kinds of exposures contribute to the carcinogenesis stages of initiation, promotion, and progression. An accumulation of reactive oxygen species may cause DNA mutations and cellular damage, which some authors suggest initiate most of carcinogenesis [23]. Reactive oxygen species can be byproducts of normal endogenous cellular metabolism; they may be produced during respiration, by neutrophils and macrophages during inflammation, or by mitochondria-catalyzed electron transport chain reactions [23,25]. Reactive oxygen species can also be produced by exogenous exposures, including nitrogen oxide pollutants, smoking, pharmaceuticals, and radiation. Reactive oxygen species cause oxidative stress, which can induce cancer-causing DNA mutations, damage cellular structures including lipids and membranes, oxidize proteins, and alter signal transduction pathways that enhance cancer risk [23,26,27].

Though this is a promising area of research, clinical trials that have used exogenous antioxidants or free-radical scavengers (such as vitamin E, vitamin C, or β-carotene) as chemopreventive agents have, on the whole, been markedly unsuccessful, and even harmful in some cases. Two trials testing β-carotene as a chemopreventive agent in male smokers and asbestos workers at high risk of developing lung cancer, the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial (ATBC) and Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET) studies, showed that high doses of synthetic β-carotene actually increased risk of lung cancer [28,29]. It is unclear how to extrapolate these results to people of average risk using natural forms of the vitamins in low, normal, or high doses. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded that β-carotene supplementation is unlikely to provide important benefits and might cause harm in some groups [30]. A study of vitamin E supplementation for preventing second primary head and neck cancers showed that vitamin E supplementation was associated with increased risk of developing a second primary cancer and poorer survival [31]. In the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study, selenium supplementation did not decrease the incidence of basal cell or squamous cell skin cancer; however, secondary analyses suggested that selenium supplementation reduced the incidence of and mortality due to cancers in other sites, the most promising of which is prostate cancer prevention [32]. The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) for prostate cancer prevention is designed to test whether selenium and vitamin E supplementation can prevent prostate cancer [33] and another trial is testing the cancer prevention effect of selenium in men with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) [34].

MULTIVITAMIN AND MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS A recent synthesis of randomized, controlled trials assessed the efficacy of multivitamin and supplement use for cancer prevention [35]. The authors concluded that the evidence is currently insufficient to prove the presence or absence of benefits. However, two trials did show an effect. In poorly nourished Chinese living in Linxian, the combined supplementation of β-carotene, α-tocopherol, and selenium reduced gastric cancer incidence and mortality rates and reduced the overall mortality rate from cancer by 13% to 21% [36–38]. In the French Supplementation en Vitamines et Mineraux Antioxydants Study (SU.VI.MAX), combined supplementation of vitamin E, β-carotene, selenium, and zinc reduced the overall cancer rate by 31% in men, but not in women [39,40].

HORMONE MODULATORS Some cancers are hormone dependent, including hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer. Breast cancer prevention trials using selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to block estrogen receptors, Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) and Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR), have been successful in decreasing breast cancer incidence in women at high breast cancer risk, though they had significant adverse effects including increased risks of endometrial cancer and osteoporosis [2,22]. Though the Women’s Health Initiative study showed that estrogen plus progesterone therapy was protective against colon cancer, the increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease indicate that it is not an appropriate cancer prevention strategy [41]. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) tested the effects of finasteride, a 5-α-reductase inhibitor, on prostate cancer incidence and found that though it inhibited the formation of prostate cancer overall, it was associated with increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer and sexual side effects [42]. The ongoing Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Cancer Events (REDUCE) trial is testing the effects of dutasteride, a dual 5-α-reductase inhibitor, in men with an increased risk of developing prostate cancer [43]. In men with high-grade PIN, the SERM toremifene decreased the incidence of prostate cancer [44].

Vitamin D is involved in regulating bone metabolism. Vitamin D and its analogs have been receiving a considerable amount of attention for their possible antiproliferative roles in the prevention of cancer in many sites, including prostate, gastrointestinal, breast, endometrial, skin, and pancreatic cancers [45]. Clinical trials are underway to test these hypotheses.

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS Observational studies have shown that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use is associated with lower risk of breast and colon cancer occurrence [46,47]. Two clinical trials of COX-2 inhibitors, rofecoxib and celecoxib, to prevent colorectal cancer in high-risk individuals showed that they were effective; however, these drugs simultaneously increased risk of cardiovascular disease [48–50]. A recent risk:benefit analysis showed that in 1000 patients with colonic adenomas, celecoxib use would prevent 1.6 colorectal cancers but would cause 12.7 cardiovascular disease events [51]. Therefore, COX-2 inhibitors are not being recommended for cancer prevention.

Surgery

If an individual is considered to be at high risk for developing a specific cancer, he or she may be offered the option of surgically removing the organ or tissue. Women at high breast or ovarian cancer risk may have prophylactic mastectomies or oophorectomies. This approach is not without consequence, such as disfigurement and inability to conceive, and is not acceptable to many women [52,53]. Individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis or longstanding ulcerative colitis may choose to have colectomies, but morbidity, mortality, and quality of life issues should be considered [54].

Vaccinations

Vaccinations have also been successful in preventing some cancers. The hepatitis B vaccine has been shown to be effective in preventing chronic hepatitis, which often progresses to liver cancer [55]. More recently, the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine was shown to be effective at preventing HPV infection and precancerous lesions, which can cause cervical cancer [56]. The HPV vaccine is perhaps an unprecedented approach to cancer prevention in that it may be given to all sexually active females, regardless of their risk of cervical cancer. The feasibility and acceptability of implementing these strategies on a population-wide basis is under debate, especially in children [57]; however, the proof of principle has been established.

CAM CANCER PREVENTION THERAPEUTICS

As stated earlier, some conventional therapies used for cancer treatment, such as tamoxifen, are applied to high-risk individuals for cancer prevention. Likewise, many of the CAM therapies discussed elsewhere in this book that are used for cancer treatment are also used by cancer-free individuals for cancer prevention. The agents have varying levels of research evidence to support their use, and most of the evidence is from in vitro and animal studies, rather than clinical trials. Few clinical trials have been conducted in CAM cancer prevention; thus the use of these agents is primarily based on theoretical and hypothesized mechanisms. CAM cancer prevention therapeutics are presented in the following section under two broad categories: those that are biological agents and those that are behavior based.

BIOLOGICAL AGENTS

A wide variety of CAM biological agents have possible applications for cancer prevention. These include special diets, botanicals (also called herbs), vitamins, minerals, and other dietary supplements.

Special Diets

To date, an abundance of data is available to suggest that people who have high intake of fruits and vegetables are less likely to develop cancer than those with low intake [12]. The data are less clear regarding which specific vegetables should be consumed, during what phase of life, and for how long. Data on specific dietary patterns that are not considered CAM, such as the Mediterranean diet or eating a low-fat diet, suggest that eating in a specific pattern on a regular basis can have cancer prevention effects [12]. One dietary pattern that is gaining in popularity and that may be on the cusp between conventional medicine and CAM is a “whole foods” diet. A whole foods diet is one that emphasizes eating foods, especially grains, fruits, and vegetables, which are as close to their natural form as possible in order to benefit from the phytonutrients and fiber present, while avoiding additives that are in processed foods. However, it appears that only a small number of individuals have the inclination or ability to fully adopt this way of eating and preparing foods.

Other dietary patterns may be considered “CAM” because they are not followed by large numbers of individuals and are considered more out of the mainstream. These include vegan, raw foods, and macrobiotic diets. Vegan refers to not eating any animal products, usually for ethical and health reasons. A raw foods diet takes this one step further by eating a vegan diet and limiting the use of heat in order to preserve the naturally occurring plant enzymes and proteins and to prevent the formation of carcinogens, which occurs with heating proteins and carbohydrates [58]. A macrobiotic diet emphasizes locally grown, organically grown whole-grain cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruit, seaweed, and fermented soy products, combined into meals according to the principle of balance between yin and yang properties [59]. Although the epidemiological and clinical trial literature is sparse, the data suggest that adopting diets that promote increased fruit and vegetable consumption leads to commensurate reduction in fat and calorie intake, both of which have separately been associated with decreased cancer risk [12,60].

A diet which restricts caloric intake, also known as a hypocaloric diet, is hypothesized to reduce the occurrence of chronic disease, including cancer [61]. However, most of this evidence is based on animal studies and recent human data suggest that short-term caloric restriction may increase incidence of some cancers [62].

Some methods of producing and preparing food are hypothesized to prevent cancer by reducing exposure to carcinogens. This includes eating organically grown food to avoid pesticides and not cooking with or storing food in plastics to avoid chemicals that may leach into food.

Botanicals

Many plants contain phytochemicals that have potential anticancer properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune modulation, modulation of detoxification enzymes, hormone modulation, and adaptogenic effects. Historically, these botanicals have often been used as foods, spices, and medicines [63]. Few of the agents have undergone phase III trials to demonstrate efficacy for cancer prevention; therefore, the data are insufficient to derive specific recommendations on formulations, doses, and duration of use.

ANTIOXIDANTS Most plants contain some form of antioxidants, typically found in their pigments and/or chemical defensive agents that are used to deter predators. As already stated, antioxidants are hypothesized to be beneficial for cancer prevention because they may prevent the formation of free radicals, which can lead to DNA damage and they may repair oxidative damage. Botanical compounds have been identified, which contain particularly high levels of antioxidants including curcumin in turmeric (Curcuma longa) [64], epigallocatechin-3- gallate (EGCG) in green tea (Camellia sinensis) [13,65], resveratrol in red grapes, peanuts, and berries [66], silymarin in milk thistle (Silybum marianum) [21], 6-gingerol in ginger (Zingiber officinale) [13,67], lycopene in tomatoes [12,68], and polyphenols in pomegranate juice [69].

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS As stated earlier, inflammatory agents in the body, such as prostaglandins, are potentially carcinogenic. A number of botanical agents are known to have substantial anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) or other part of the inflammation pathway. Curcumin [13,70,71] and ginger [12,67,72] are two of the most potent anti-inflammatory botanical agents. Preliminary in vitro and case report data suggest interesting anti-inflammatory effects of a combination herbal anti-inflammatory agent, Zyflamend®, on prostate cancer cells and in men with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) (without prostate cancer) [73,74].

IMMUNE FUNCTION MODULATORS A well-functioning immune system is hypothesized to be beneficial for cancer prevention because circulating immune cells can destroy nascent cancer cells. Some of the botanicals that have been identified for their effects on improving immune function include medicinal mushrooms, astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus), and ginseng (Panax ginseng). Several varieties of immune-modulating mushrooms have been identified, including Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi), Coriolus versicolor, and maitake (Grifola frondosa) [75,76]. Astragalus, frequently used in Chinese medicine, is not as well studied but historically has been shown to improve immune function [77]. Panax ginseng has also demonstrated immune system–enhancing effects [77,78].

BIOTRANSFORMATION ENZYME MODULATORS Biotransformation enzymes modulate the effects of chemical carcinogens. Compounds in various botanical agents have been shown to induce or inhibit enzymes related to cancer risk. As discussed earlier, cruciferous vegetables can inhibit phase I enzymes and induce phase II enzymes. Indole-3-carbinol is a compound found in cruciferous vegetables. It has been shown to upregulate hepatic enzyme systems that metabolize endogenous carcinogens. Early-phase human trials have shown that it may have some applicability in lung, cervical, and breast cancer; however, liver toxicities may prevent its widespread use [79]. Curcumin has been shown to inhibit phase I enzymes and induce phase II enzymes, such as glutathione-S-transferase [80].

HORMONE REGULATORS Given that some cancers are hormone dependent, for example, some forms of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate, and testicular cancer, botanicals that modulate endogenous hormone levels may be indicated for cancer prevention. There has been ongoing debate on the role of soy products in cancer prevention. Isoflavones are found in leguminous plants, such as soy. The most active isoflavones are diaidzein and genistein, both of which have been shown to possess both estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities. The current consensus is that there is insufficient evidence to recommend soy isoflavones as a cancer prevention tactic and therefore soy should be eaten in moderation [81].

Animal and observational data suggest that green tea consumption may lower blood estrogen levels, thus lowering breast cancer risk, while limited data suggest that black tea may increase breast cancer risk [82].

ADAPTOGENS Adaptogens are botanicals used to stimulate the central nervous system to decrease stress, decrease depression, eliminate fatigue, and enhance work performance. This may be of importance in psychoneuroimmunological models of cancer, which hypothesize that a positive neurological state leads to a well-functioning immune system. Botanicals used for this purpose include Panax ginseng, Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcos senticosus), schisandra (Schisandra chinensis), and rhodiola (Rhodiola rosea) [78,83–85]. However, there is conflicting evidence whether Panax ginseng and rhodiola exert estrogenic effects, which would contraindicate their use in estrogen-dependent cancers [86–88].

COMBINATION FORMULAS Historically, botanical preparations have been used in combination to make use of synergistic properties between individual botanical agents. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurvedic and Western botanical formulations operate on this principle. Two Western botanical formulations, Essiac tea and Hoxsey formula, have made claims to prevent and treat cancer. However, to date these claims have not been supported with scientific evidence [89,90].

Vitamins and Minerals

As discussed earlier, epidemiological studies suggest that vitamin and mineral intake can affect risk of developing specific cancers. Some people have interpreted this as evidence to support the use of mega doses of these agents. Taking doses of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals above that which is found in a standard multivitamin may be considered CAM. Orthomolecular medicine, coined by Linus Pauling, PhD, refers to the practice of preventing and treating disease by providing the body with optimal amounts of substances which are natural to the body, which often results in the use of high doses of natural compounds [91]. Given the results from the ATBC and CARET trials discussed earlier, it is unclear how efficacious this high-dose approach may be. These studies were in high-risk populations and used high doses of synthetic forms of the vitamins. Coenzyme Q10 is a potent antioxidant but has limited clinical data to support its use specifically for cancer prevention [92].

Other Dietary Supplements

Other dietary supplements have been proposed as possible cancer prevention therapies. Some of the more promising dietary supplements include melatonin, omega-3 fatty acids, probiotics, and prebiotics.

Changes in circadian rhythm due to night shift work or increased ambient light dysregulates melatonin levels. Melatonin supplementation is hypothesized to have oncostatic, cytotoxic, and antiproliferative effects [93].

Omega-3 fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have several proposed mechanisms for lowering cancer risk. The most studied mechanism is inhibiting the formation of proinflammatory and procarcinogenic eicosanoids, such as prostaglandins [94,95].

Pro- and prebiotics may have chemopreventive roles in gastrointestinal cancer. Probiotics, such as Lactobacillus sp., are hypothesized to confer chemopreventive benefits in gastrointestinal cancers by deactivating procarcinogenic cellular components of microorganisms, inhibiting and/or inducing colonic enzymes, controlling growth of harmful bacteria, stimulating the immune system, and producing physiologically active anticancer metabolites [96–98]. Prebiotics are short-chain carbohydrates, such as undigested polysaccharides, resistant starches and fiber, enhance the formation of beneficial bacteria and of short-chain fatty acids that can reduce oxidative stress and induce the chemo-preventive enzyme glutathione transferase [97,98].

BEHAVIORAL APPROACHES

One of the most basic differences between conventional and CAM approaches to cancer prevention is that a CAM approach often encourages people to do things beyond ingesting biological agents in order to reduce risk of developing cancer. These activities can be referred to as “mind-body” and “energy” medicine. Similar to many of the biological agents, these are lacking clinical trials to demonstrate efficacy, and are based on theoretical and hypothesized mechanisms.

Mind-Body Medicine

Available evidence links stress, behavioral response patterns and resultant neurohormonal and neurotransmitter changes to cancer development and progression [99]. Collectively this work suggests that stress management may modify neuroendocrine deregulation and immunological functions that potentially have implications for tumor initiation and progression [99]. Clinical studies indicate that stress, chronic depression, social support, and other psychological factors may influence cancer onset and progression [99]. This area of medicine is often called mind-body medicine, or psychoneuroimmunology.

There are a wide variety of types of therapies that fall under the rubric of mind-body medicine [99]. Sensory therapies include aromatherapy, massage, touch therapy, music therapy, and creating a calm and/or beautiful space such as a room with a view or a healing garden. Cognitive therapies include meditation, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), guided imagery, visualization, hypnosis, and humor therapy. Expressive therapies include writing, journaling, art therapy, support groups, individual counseling, and psychotherapy. Physical therapies include dancing, yoga, and tai chi. Though none of these approaches have been shown to prevent cancer per se, some of them have been shown to affect parameters associated with cancer development, such as improving immune function and decreasing circulating cortisol. It is of note that an early study showed that support groups increased survival in breast cancer patients [100]. However, these results have not been replicated and there is no evidence to date supporting the use of psychological interventions to prevent cancer [101].

Energy Medicine

Energy medicine refers to practices that use nonmaterial stimuli for the purposes of healing [102]. These stimuli may be via artificially generated electromagnetic fields, such as pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, or via human generated energies, such as reiki, Qigong, and healing touch. The hypothesized mechanism of action is that the applied energy causes a change in the human biomagnetic energy field which can affect a biochemical response in the body. In terms of cancer prevention, many of these energy medicines theorize that an early correction of stagnation or imbalances in energy patterns may lead to the prevention of cancer [103]. These theories are based on the concept that flows of energy or essence patterns in the body are dynamically balanced and must not be blocked. If blockages do occur, diseases can develop, including cancer. Energy medicine systems attempt to relieve these blockages via methods such as acupuncture, Reiki healing sessions, and qigong exercises. Some human studies have shown an effect of these energy therapies on parameters related to cancer incidence including increasing secretary immunoglobulin A [104], enhancing immune system response [105], and reducing stress [106]. A study in mice has shown a decrease in the growth of induced lymphoma via external Qigong [107].

Other Systems of Healing and Health

All cultures have systems to promote health and healing, many of which are highly developed and very different from the conventional medical model accepted in Western societies. The conventional medical model tends to be best at responding to and treating disease, and relatively ineffective at preventing disease. The goal of many of these other systems of healing is to promote health and wellness, thereby preventing disease. Some of these other systems include TCM, Ayurvedic medicine, Tibetan medicine, and Native American medicine. Each of these is briefly discussed in the following sections. It is important to note that though each tradition is a rich, complete system unto itself, practitioners within each tradition may be diverse in terms of their interpretations, approaches and therapeutics for preventing, diagnosing, and treating disease. The descriptions provided here are very basic. Even for clinicians practicing within the Western medical tradition, having a familiarity with other systems of healing and health may be a critical skill [108].

TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE

TCM is a medical system from China. TCM therapeutics aim to restore the body’s balance and harmony between the natural opposing forces of yin and yang and the five elements (wood, earth, air, fire, water). An imbalance between any of these forces can block Qi, blood or phlegm which can result in disease, including cancer. Diagnostic techniques include tongue and pulse diagnosis. TCM therapeutic modalities include acupuncture, botanical formulations, Qigong, tui na (massage), moxibustion, and dietary modification [109]. TCM was popularized in the United States in the 1970s after the fall of the “bamboo curtain” [109]. Another form of Chinese medicine, Five Element acupuncture, focuses on the use of acupuncture to restore mental and spiritual balance [110].

AYURVEDIC MEDICINE

Ayurvedic medicine, Ayurveda, or “the science of life,” comes from India. A central concept to Ayurveda is that the three doshas, or body constitutions, Kapha, Pitta and Vata, need to be kept in balance to maintain health. An imbalance results in disease, including cancer. Causative factors for these imbalances include eating unhealthy foods, poor hygiene, bad lifestyle habits and environmental exposures, which, if left uncorrected, lead to the accumulation of one or more doshas somewhere in the body [111]. Diagnostic techniques involve tongue and pulse diagnosis. Ayurvedic therapeutic modalities include dietary modifications, botanical formulations, massage, precious substances, yoga, and spiritual practice [112]. Ayurveda was popularized in the United States in the 1990s by Depak Chopra [113].

TIBETAN MEDICINE

Tibetan medicine comes from Tibet, and is based on Buddhist teachings. Here, the three humors, bile, phlegm and wind need to be kept in balance. Cancer is caused by an imbalance in one, two, or all three of the humors. In addition, cancer can arise due to contaminants that have been introduced into the atmosphere and the environment. Diagnostic techniques include examination of the tongue, pulse, and urine. Therapeutic modalities include diet therapy, botanical formulations, physical activity, precious metals, and meditation [114].

NATIVE AMERICAN MEDICINE

Each indigenous tribe in the Americas has a unique healing tradition and there is not a definition that can describe a single Native American medicine [103]. However, there are some common themes in these traditions. In Native American medicine, there is not a differentiation between medicine and religion. To heal, one must acknowledge an “Inner Healer.” Many tribes teach that spirit is indivisible from mind and body and that a healthy balance, harmony and connection with spirit is vital for disease prevention [103]. Illness results when there is imbalance or disharmony and wellness occurs when balance is restored [115]. Ceremony is intrinsic to creating and maintaining harmony. It is important to note that cancer can also be caused by disturbing the sacred nature of the land [115].

Common to healing systems such as TCM, Ayurveda, Tibetan medicine, and Native American medicine is the recognition of a balance between an individual, their community, and their environment. Any disturbance in one of these areas can lead to disease, including cancer. Perhaps what we can learn from these systems of health and healing is that it behooves us to conceptualize a holistic approach to cancer prevention which incorporates body, mind, spirit, and environment.

A Vision for Future Clinical Services

Currently, in the United States there are few truly integrated medical centers providing cancer prevention care. Some cancer centers are beginning to offer risk assessment services; however, they are limited to genetic screening and medical history risk and do not have well-developed programs on prevention tactics. Two main factors that have limited the widespread provision of these services include a lack of research on efficacy of many cancer prevention approaches, and poor, if any, physician reimbursement for prevention care. In addition, patients are not reimbursed or rewarded for time and resources spent at being proactive about disease prevention. Unfortunately, all of these factors may make it confusing for individuals using conventional or CAM modalities for general health maintenance and for cancer prevention because they are without clear guidance.

In the future, it is possible that people will be able to visit specialized clinics to receive comprehensive assessments of their personal risk of developing cancer. These risk assessments will take into account the results of screening tests, personal disease history, family disease history, genetic tests, prior environmental exposures, dietary history, exercise history, and socio-economic status. New tools will be available to assess stress, immune function, and genetic risk including an individual’s ability to metabolize various substances. Once this assessment is made, people will be offered and counseled on interventions to counter their risk, including pharmaceuticals, natural compounds, dietary changes, exercise programs, and mind-body interventions. The clinics will be staffed by people with varying areas of expertise, including genetics, medical oncology, radiation oncology, health psychology, nutrition, exercise, mind-body medicine, botanical medicine, and functional medicine.

Future Research Directions

Each of the cancer prevention approaches described would benefit from further investigation. Many of these approaches are promising, but few have enough evidence to promote large-scale implementation. The gold standard for determining whether a cancer prevention approach is effective is to use cancer incidence as the endpoint in large, randomized, phase III studies. Because these trials are expensive and can be difficult to implement, early-phase trials using intermediate or surrogate markers for predicting cancer occurrence may be warranted. These endpoints include clinical, histological, biochemical, and molecular biomarkers that can demonstrate responses to chemoprevention agents, behaviors, or healing modalities [116]. These studies will need to carefully screen potentially therapeutic strategies to identify which have the most promise, which target populations will benefit the most, and what the appropriate endpoints will be.

Most CAM practitioners are trained to tailor their therapies to an individual. Increasingly, conventional medical practitioners and researchers are acknowledging the benefit of individualizing health care delivery. This approach will be especially beneficial in the area of cancer prevention where it may be difficult to implement and sustain preventive measures in large numbers of individuals. Assuming that additional effective cancer prevention modalities will be identified in the future, individuals will be asked to regularly ingest substances, change their behaviors, and/or receive vaccinations. It will be important to tailor these recommendations to an individual to make them as effective and as acceptable as possible.

Conclusion

Cancer prevention is just one aspect of optimizing health. Average-risk individuals want to know what they can do to decrease their risk of developing any disease. Individuals at high cancer risk want to know their options for decreasing their specific cancer risk. Ideally, in the future people will have access to cancer prevention centers that offer an integrated team of clinicians to coordinate medical and lifestyle recommendations, with a focus on staying well, rather than on treating disease. Ideally, some of the CAM modalities that are proven efficacious for disease prevention and/or enhancing a sense of well-being will be offered at these centers. To be sustainable, this will need to be done in the context of a medical system that invests in prevention and pays and reimburses for prevention work.

In the meantime, we can consider advocating lifestyle changes that may prevent cancer initiation and/or progression, while simultaneously helping individuals increase their sense of wellness. We can eat a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains, stay physically active, maintain a BMI of less than 25, and keep stress at bay, possibly using one of the mind-body techniques described earlier. We can know our risk of developing cancer based on age, gender, family history, and exposures and be screened appropriately. Finally, we can live a full life, keeping in mind traditional systems of medicine that promote balance between body, mind, spirit and environment.

REFERENCES

1. Alberts DS & Hess LM. (2005). (Eds.). Fundamentals of Cancer Prevention. New York: Springer.

2. Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, et al. (1998). Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 90, 1371–1388.

3. Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, Nixon DW, Shapiro A, Hoy M, et al. (2006). Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: Interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 98, 1767–1776.

4. Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, Crotty TP, Myers JL, Arnold PG, et al. (1999). Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 340, 77–84.

5. Crowell JA. (2005). The chemopreventive agent development research program in the Division of Cancer Prevention of the US National Cancer Institute: An overview. European Journal of Cancer, 41, 1889–1910.

7. Burke W & Press N. (2006). Genetics as a tool to improve cancer outcomes: Ethics and policy. Nature Reviews. Cancer, 6, 476–482.

12. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. (2007) Food, Nutrition and the Prevention of Cancer: A global perspective. Washington DC: American Institute for Cancer Research.

19. Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, Gansler T, et al. (2006). American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for cancer prevention: Reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer The Clinical Journal, 56, 254–281; quiz 313–4.

20. American Cancer Society. (2006). The Complete Guide—Nutrition and Physical Activity.

100. Larkey LK, Greenlee H, & Mehl-Madrona LE. (2005). Complementary and alternative approaches to cancer prevention. In: DS Alberts & LM Hess (Eds.), Fundamentals of Cancer Prevention. New York: Springer.

(A complete reference list for this chapter is available online at http://www.oup.com/us/integrativemedicine).

An individual’s risk of developing cancer is determined in part by genetic predisposition and lifetime exposures. Information about these factors can be used to recommend an appropriate screening schedule.

An individual’s risk of developing cancer is determined in part by genetic predisposition and lifetime exposures. Information about these factors can be used to recommend an appropriate screening schedule. Conventional approaches to cancer prevention include behavioral modifications (such as dietary changes and physical activity), biological agents (such as antioxidants, multivitamins, minerals, hormone modulators, and anti-inflammatory agents), surgery, and vaccinations.

Conventional approaches to cancer prevention include behavioral modifications (such as dietary changes and physical activity), biological agents (such as antioxidants, multivitamins, minerals, hormone modulators, and anti-inflammatory agents), surgery, and vaccinations. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches to cancer prevention include special diets, botanicals (for various properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune modulating, hormone modulating, and adaptogenic effects, and the induction of biotransformation enzymes), vitamins and minerals, other dietary supplements, mind-body therapies, and energy therapies.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches to cancer prevention include special diets, botanicals (for various properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune modulating, hormone modulating, and adaptogenic effects, and the induction of biotransformation enzymes), vitamins and minerals, other dietary supplements, mind-body therapies, and energy therapies. Non-Western systems of healing such as Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Tibetan medicine, and Native American medicine offer their own perspectives on what causes cancer and what can be done to prevent cancer.

Non-Western systems of healing such as Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Tibetan medicine, and Native American medicine offer their own perspectives on what causes cancer and what can be done to prevent cancer. An integrative approach to cancer prevention encourages individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices, use appropriate cancer screening technologies, and maintain a sense of wellness and balance.

An integrative approach to cancer prevention encourages individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices, use appropriate cancer screening technologies, and maintain a sense of wellness and balance.