11

Massage Therapy

LISA W. CORBIN

KEY CONCEPTS

Patients with cancer often suffer physical symptoms and psychological stress. Massage therapy, widely used by healthy people for relaxation, may have other specific benefits for patients in all stages of cancer treatment.

Patients with cancer often suffer physical symptoms and psychological stress. Massage therapy, widely used by healthy people for relaxation, may have other specific benefits for patients in all stages of cancer treatment.

The use of massage therapy, with specific precautions in certain situations, is safe for patients with cancer.

The use of massage therapy, with specific precautions in certain situations, is safe for patients with cancer.

There are few large, well-designed trials of massage therapy for patients with cancer; existing research suggests the most benefits for lymphedema and anxiety.

There are few large, well-designed trials of massage therapy for patients with cancer; existing research suggests the most benefits for lymphedema and anxiety.

Though there is even less substantial research to support other claims, massage is often suggested for improved postoperative wound healing, sleep, pain, fatigue, constipation, and improved immune function

Though there is even less substantial research to support other claims, massage is often suggested for improved postoperative wound healing, sleep, pain, fatigue, constipation, and improved immune function

Physicians caring for patients with cancer should ask all patients about the use of massage, consider recommending massage for anxiety and distress, and help guide the patient to a qualified massage therapist.

Physicians caring for patients with cancer should ask all patients about the use of massage, consider recommending massage for anxiety and distress, and help guide the patient to a qualified massage therapist.

Massage therapy, a complementary therapy known primarily for its use in relaxation, may also benefit patients with cancer in other ways. However, the use of massage techniques in patients with cancer requires special considerations. While safe and efficacious for some patients, it may be harmful or ineffective in other situations. Risks can be minimized and benefits maximized when the clinician feels comfortable discussing massage with his or her patients. This chapter reviews and summarizes the literature on massage and cancer to provide the clinician with reliable information regarding the safe, appropriate use of massage therapy for patients with cancer, and thus to help facilitate discussions with patients.

Defined by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), “massage therapy” is classified within the category of “manipulative and body-based therapies” as an “assortment of techniques involving manipulation of the soft tissues of the body through pressure and movement” (http://nccam.nih.gov/). There are many different styles of massage therapy (such as Swedish, Rolfing, Deep Tissue, and Neuromuscular). A detailed comparison of techniques is not relevant to this text; instead, the clinician should work with a massage therapist skilled in treating patients with cancer and who can employ the techniques appropriate for the situation.

Almost all cultures have developed massage therapy as it seems instinctual to rub and press an area of muscular pain. References date back at least as far as 1600 BC. Hippocrates mentioned massage (around 400 BC), and massage was used and referenced as a medical therapy until the focus of medical care shifted to the biological sciences in the early 20th century. In the 1970s, massage in the United States found renewed interest, especially for athletes. Over the past 25 years, the therapeutic uses of massage have broadened, and research has sought to investigate its physical, physiological, and psychological effects.

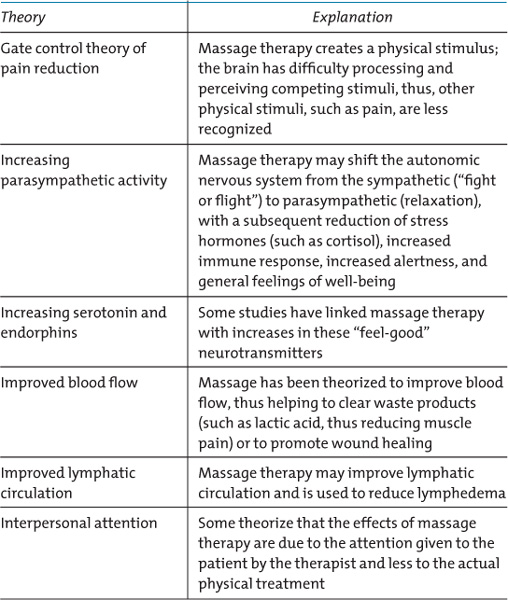

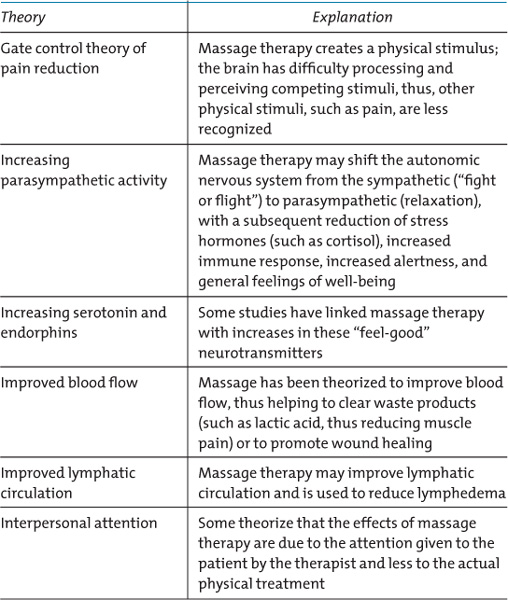

Proposed theories abound to explain the mechanism of action of massage therapy. Few of these theories are well-tested, however, and there is little to no correlation of bench research (such as the observation of an acute increase in natural killer cell number and activity following massage (Hernandez-Reif, 2005; Zeitlin, Keller, Shiflett, Schleifer, & Bartlett, 2000)) to clinical outcomes (such as improved disease-free survival for patients with cancer). Theories on mechanisms of action are summarized in Box 11.1 (Field, et al., 1998; Moyer, 2004). The lack of a thorough understanding of mechanism of action or clinical correlation should not necessarily dissuade the physician from recommending massage therapy, however, as these theories lend plausibility to the anecdotal reports and small studies supporting efficacy discussed in a subsequent section. Ideally, the physician will have a candid discussion with his or her patient about the potential benefits and safety issues framed in the context of studies which support benefit.

Patients with cancer may suffer physical symptoms and psychological stress. Physical symptoms such as pain or early satiety may be due to the location of the tumor; other symptoms, such as constipation or nausea, can result from the medications used to treat these symptoms. Patients who have undergone cancer treatment may have symptoms related to the treatment, such as postsurgical pain or lymphedema. The burden of psychological stress, anxiety, and depression in cancer patients cannot be overemphasized. Depression has been estimated to be four times as common in cancer patients as compared with that in the general population. Anxiety may lead to patients overestimating the risks associated with treatments or worsen their perception of their physical symptoms. Because of undertreated psychological symptoms, patients with cancer may not follow through with treatment recommendations or may report a higher severity of physical symptoms.

BOX 11.1. Theories of Mechanism of Action of Massage Therapy

Massage therapy has been increasingly employed and investigated as a therapeutic intervention to reduce symptoms in cancer patients. Studies are typically small or poorly designed, however, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions (see section on benefits).

Indeed, studies have shown that patients with cancer are increasingly drawn to massage therapy in an attempt to alleviate symptoms (Ashikaga, Bosompra, O’Brien, & Nelson 2002; Coss, McGrath, & Caggiano, 1998; Lengacher, 2002). In a study published in 2000, 26% of 453 adult patients surveyed at MD Anderson Cancer Center acknowledged using massage therapy (Richardson, Sanders, Palmer, Greisinger, & Singletary, 2000); in 2001, 20% of 100 patients seeking care at a private cancer center reported having received massage therapy (Bernstein & Grasso, 2001); although in a prospective study of 50 patients receiving radiation for prostate cancer only 7% of patients reported receiving massage therapy (Kao & Devine, 2000). 60% of 169 hospices responding to a survey published in 2004 reported that they offered complementary medicine services at their hospices, with massage therapy the most commonly offered service (available at 83% of the hospices offering CAM therapies) (Demmer, 2004). Despite the popularity and availability of massage therapy for patients with cancer, some patients and their family members remain unaware of the potential uses of massage as a therapy for symptom control.

Over 20% of patients with cancer report using massage therapy as an adjunct to conventional care. Massage is the most commonly available CAM therapy in US hospices.

Clinicians are aware that patients use complementary therapies, including massage therapy, but often do not discuss it with patients (Bourgeault, 1996). It has been widely postulated that open discussion between physicians and patients about CAM may result in an enhanced physician/patient relationship and encourage enhanced compliance with recommended treatments.

Safety of Massage Therapy

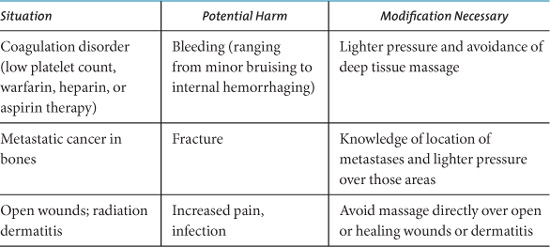

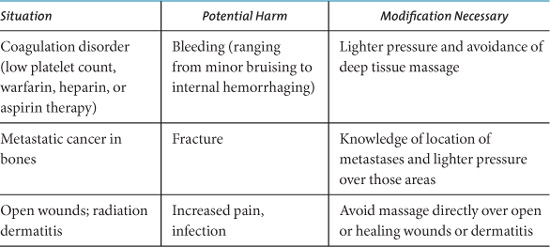

Overall, therapeutic massage is widely considered to be safe, though adverse events have been reported. Healthy patients may experience an allergic reaction to the lubricants used, bruising, swelling of massaged muscles, or a temporary increase in muscular pain; absolute risk of these events is unknown. Pregnant women should avoid prolonged positioning on their back. Case reports have reported or theorized serious adverse events, including fractures and dislocations; internal hemorrhage, and hepatic hematoma (Trotter, 1999); dislodging of deep venous thrombosis and resultant embolism of the renal artery (Mikhail, Reidy, Taylor, & Scoble, 1997); and displacement of a ureteral stent (Kerr, 1997). A recently published review of cases reported in the literature and randomized controlled trials of massage therapy found that few reported adverse events (Ernst, 2003). Cancer patients may be at higher risk for these problems, requiring modification of technique to avoid them. Table 11.1 shows specific situations often encountered with cancer patients, the potential harm of massage in these situations, and suggestions on ways to decrease risk. There has been no evidence that massage therapy can spread cancer, although direct pressure over a tumor is usually discouraged.

Table 11.1. Circumstances with Potential for Massage-Related Adverse Events.

There is no evidence that therapeutic massage can spread cancer.

Certainly, massage should never be advocated as a substitute for potentially curative oncological care. Health care providers should also realize that while massage therapy can be safe for their patients with cancer, massage therapists may also be suggesting certain herbs or other complementary medicine therapies to their patients that may put the patient at risk.

Benefits of Massage Therapy

Few studies have adequate numbers of patients to investigate efficacy of massage therapy for symptoms in cancer patients. A meta-analysis (see following text) found only eight randomized clinical trials, with a total of only 357 patients. Investigators have found large trials difficult to design and carry out; one report described unforeseen challenges including late-stage cancer patients being too ill to participate and health care providers withholding referrals to the study because of a bias against having their patients possibly randomized to the non-massage therapy control group (Westcombe, 2003).

A meta-analysis by the Cochrane collaborative group reviewed randomized controlled trials published prior to May 2002 that investigated the use of massage to reduce symptoms in patients with cancer. Their search strategy yielded eight randomized controlled trials with a total of 357 patients. The authors noted that a reduction in anxiety (19% to 32% in four studies; 207 patients) was most commonly seen. Only three studies with a total of 117 patients measured pain; a decrease was noted in just one study. Criticisms of these studies included the small number of subjects enrolled and the use only of standardized massages that did not allow the therapist to direct the massage based on the patient’s specific situation. Similarly, only two studies (71 patients) demonstrated a reduction in nausea. Individual studies showed improvement in other common symptoms, such as sleep (Fellowes, Barnes, & Wilkinson, 2004).

A few randomized controlled trials have been published since the meta-analysis. In the United Kingdom, Soden et al. randomized 42 hospice patients with cancer to receive massage, massage plus aromatherapy, or no intervention over a 4-week period. They did not find any significant benefits for pain, anxiety, or quality of life, although statistically significant improvements in sleep were seen in both massage groups, and a reduction in depression was noted in the massage-only group. Patients with higher initial levels of psychological distress had more response to the massage interventions (Soden, Vincent, Craske, Lucas, & Ashley, 2004).

The largest study on massage for symptom reduction in cancer patients to date was published by Post-White et al. in 2003. This group randomized 230 cancer outpatients to receive a standardized massage, healing touch (an intervention whereby the practitioner is believed to modify a patient’s energy fields by motion of his or her hands near or gently on the patient), or the presence of a staff member in the room in a crossover design. Each intervention was given weekly for 45 minutes for 4 weeks. Physiological effects such as decreased heart rate and respirations were seen in all three groups; massage therapy lowered pain (with a reduction in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications also noted) and anxiety, and therapeutic touch also lowered anxiety (Post-White, et al., 2003).

A nonrandomized study of a simple 10-minute foot massage by nurses showed immediate benefits for pain, nausea, and anxiety in 87 hospitalized patients with cancer. Though conclusions cannot be drawn without a control group, further study is warranted as this intervention would be relatively simple and easy to deliver (Grealish, Lomasney, & Whiteman, 2000).

A large, retrospective, observational study of pre- and postmassage symptom scores of 1290 in- and outpatients seen over a 3-year period at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (3609 massages delivered) showed an average 50% reduction in symptoms (ranging from 21% improvement for nausea to 52% for anxiety) following massage. Follow-up surveys at 48 hours showed persistence of the benefit. Patients rated symptoms including pain, fatigue, anxiety, nausea, and depression on a 0 to 10 scale. For whatever symptom rated the highest on premassage assessment, improvement was 54%. Results were felt to be clinically significant and, although the study did not have a randomized design, it certainly supports the idea of massage’s utility in symptom control for patients with cancer (Cassileth & Vickers, 2004).

Massage also has been proposed to reduce stress and increase relaxation for caregivers of patients with cancer. One study investigated these symptoms in 42 spouses of patients with cancer randomly assigned to a trial group receiving a single 20-minute therapeutic back massage or to a control group. Mood assessed preintervention, immediately postintervention, and 20 minutes postintervention showed improvement postintervention in the massage group (Goodfellow, 2003). A separate trial assigned 36 caregivers of patients undergoing autologous hematopoetic stem cell transplant to receive two 30-minute massage sessions (13 participants), two 30-minute healing touch sessions (10 participants), or one 10-minute nurse visit (13 patients). Anxiety and depression as well as fatigue were significantly reduced in the massage group (Rexilius, Mundt, Eckson Megel, & Agrawal, 2002).

Massage therapy may also reduce stress and anxiety for caregivers of oncology patients.

A specific massage technique, “manual lymphatic drainage” (MLD), has been employed to decrease breast cancer related lymphedema and is commonly used in combination with support/compression garments, skin care, and exercise. Despite widespread use, MLD has not been rigorously studied. An exhaustive Cochrane collaboration search identified just two randomized studies, noted here (Preston, Seers, & Mortimer, 2008). A randomized crossover design study specifically examined this technique in 31 women with breast cancer-related lymphedema and showed significantly reduced limb volume as well as symptoms such as pain and heaviness. Quality of life was positively affected, and sleep improved (Williams, Vadgama, Franks, & Mortimer, 2002). However, in a study of 42 women with mastectomy-related lymphedema comparing MLD along with compression garments versus compression garments alone, the addition of MLD did not offer additional improvement in lymphedema (Andersen, Hojris, Erlandsen, & Anderson, 2000).

Abdominal massage has been advocated to reduce constipation; a review of trials of massage for chronic constipation in 1999 concluded that the numbers of patients studied was too small to make definitive statements on efficacy (Ernst, 1999). Massage has been promoted to improve immune function, but actual studies are small and inconclusive (Field, 2001). Massage therapy is also commonly advocated to cancer patients to help promote postoperative wound healing and reduce scar tissue formation, and to help release metabolic waste by improving circulation. A Medline search failed to locate any published trials demonstrating the efficacy of massage therapy for these indications. Future well-designed trials may wish to look at massage therapy for these indications.

Research on the benefits of massage therapy is ongoing. For the clinician who is interested in information on current clinical trials involving massage and cancer can be found by searching the NIH CRISP database (http://clinicaltrials.gov). As of August 2008, there were 11 open and recruiting studies listed on this site investigating the effects of massage therapy on patients with cancer. Six of the 11 have pain and other physical and functional symptoms as the primary outcomes; three are looking at MLD for breast cancer related lymphedema. Two of the larger trials are discussed in the subsequent paragraphs.

One recently completed NIH-funded multi-site randomized controlled trial enrolled 380 patients with advanced cancer (90% of whom were in hospice care) and pain (at least 4 on a 0–10 point pain scale) to either 6 30 minute massage therapy visits or 6 30 minute visits of non–moving touch (administered by a volunteer instructed to place his/her hands in predefined locations on the patient’s body for a total of 30 minutes) over a 2-week period. Participants received an average of 4.1 visits. The non–moving touch control was chosen to control for the benefits of attention and simple touch. Pain was reduced over the course of the study to a similar extent in both groups; however, massage therapy showed a greater benefit in short-term pain control. Massage therapy was safe in this population, though patients with known coagulopathies or unstable spines were excluded. (Kutner JS, Smith MC, Corbin L, Hemphill L, Benton K, et al., 2008. In press)

The NIH is also funding a study of massage therapy to reduce fatigue in patients with certain cancer types; this study (currently in analysis phase) randomized patients to massage, sham bodywork, or usual care and was based at the University of California San Francisco. Final results are not yet available.

In summary, trials of massage therapy in cancer patients give the strongest evidence for its ability to decrease anxiety and distress. Massage may likely decrease pain but the number of patients studied is small; the efficacy of massage on other symptoms associated with cancer as well as on the number of medications used for symptom control also warrants more study. If massage therapy is indeed beneficial in cancer patients, perhaps more care centers for patients with cancer will make massage therapy available.

Discussing the Use of Massage Therapy with Cancer Patients

Cancer patients often use complementary medical therapies, including massage therapy, in conjunction with conventional treatment. Although massage is generally safe, cancer patients, particularly those undergoing active treatment, are at higher risk for complications. The clinician should note the presence of comorbid conditions which may put the patient at higher risk for complications, such as anticoagulant use, heart failure, deep venous thrombosis, cellulitis, the presence of catheters, pregnancy, or bone metastases. If the patient has any of these comorbidities, he or she should be advised to work with a therapist experienced in medical massage or cancer massage who will feel comfortable making the appropriate modifications in technique necessary to decrease risk. Secondarily, patients should be encouraged to consider the use of massage therapy for adjunctive management of pain and anxiety. If a patient is interested in using massage therapy, the physician should help them find a qualified therapist (see Box 11.2 for further details).

Philosophy and education of therapists is variable, with some massage therapists under the mistaken belief that cancer is a contraindication for massage and others perhaps discouraging patients from receiving potentially curative conventional care or promoting potentially harmful therapies. Thus, finding a massage therapist experienced and comfortable with both cancer patients and the conventional care commonly used is paramount.

Clinicians can help patients find a qualified massage therapist. Given that many cancer centers, hospitals, and hospices now have Integrative Medicine programs offering massage therapy, clinicians can ideally refer patients to seek treatment in these settings. If no such programs are available, the clinician should encourage the patient to interview potential therapists or should do so himself or herself to establish an ongoing consultant relationship for future referrals.

When interviewing a potential massage therapist, ask about education and experience including licensing and certification. Consider only massage therapists who have a minimum of 500 hours of training. Massage therapy schools voluntarily meeting criteria set by the Commission on Massage Therapy Accreditation have achieved and maintained a level of quality, performance, and integrity that meets meaningful standards. A directory of accredited programs is available on the Commission’s web site (http://www.comta.org/Home.htm). Specialized programs for advanced training in massage care of the patient with cancer are also available; additional education and experience in working with cancer patients is a must. Specialized programs are not standardized, however. Overall, studies of massage in other conditions have suggested that the greatest benefits are seen with the most experienced massage therapists (Furlan, Brosseau, Imamura, & Irin, 2002).

BOX 11.2. Finding a Qualified Massage Therapist

Not all states regulate massage therapists. A current list is available from the American Massage Therapy Association (http://www.amtamassage.org/about/lawstate.html). If a therapist is licensed, the initials “LMT” (Licensed Massage Therapist) or “LMP” (Licensed Massage Practitioner) are used after the therapist’s name. In other nonlicensing states, a therapist should have “CMT” (Certified Massage Therapist) as a minimum qualification. Beyond this, the initials NCTMB indicate that the therapist has voluntarily taken and passed an exam given by the National Certification Board of Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork.

The right massage therapist will be knowledgeable about risks and benefits of massage in a cancer population and should be comfortable communicating with the referring physician on an ongoing basis. They should see themselves as an extension of the patient’s healthcare team, not as a replacement. Some massage therapists may have experience with other complementary therapies and should agree to encourage the patient to discuss any suggestions on other therapies with their clinician.

The cost of massage therapy visits is relatively trivial when compared with the cost of some medications and other conventional treatments for symptom control, but may be prohibitive for some patients nonetheless as it is often not covered by insurance. There may be funds available for patients through charitable organizations, and this option should be explored. The cost of massage therapy will typically qualify for reimbursement through medical flexible spending accounts and usually will count toward medical expenses that can be itemized on federal taxes. Patients should be encouraged to verify this with their employer and/or tax accountant or attorney. A relatively new and intriguing area of research in massage therapy is exploring the idea of teaching caregivers to massage patients undergoing cancer treatment. If this approach can be shown to be feasible and effective in terms of reduced symptoms in cancer patients, it will present a much more cost-effective and convenient approach.

Summary and Conclusions

Over 20% of patients with cancer use massage therapy, with most patients using massage and other complementary therapies along with conventional treatments. Though physicians increasingly recognize that patients use complementary therapies, many are reluctant to bring the subject up with their patients. Discussion of CAM with patients may enhance the doctor–patient relationship, improve compliance with conventional treatments, and allow the physician to promote nonpharmacological approaches to symptom management. A nice general review of discussion complementary and alternative medical therapies with cancer patients was published in 2002 (Weiger, et al., 2002).

Given what is known from research studies, massage should be promoted to cancer patients as a therapy to help reduce stress and anxiety. Though the ability of massage therapy to reduce symptoms other than anxiety has not yet been conclusively demonstrated, the low likelihood of harm and studies leaning towards proving benefit for pain and other symptoms makes massage therapy an attractive adjunct to conventional care. Massage should not be used as a substitute for conventional cancer care, and clinicians should recognize and discuss that massage practitioners may promote other potentially harmful unconventional therapies. Massage therapy should be accepted and condoned as a potentially beneficial intervention for symptomatic relief in patients with cancer, and can be safely incorporated into conventional care of cancer patients.

GENERAL REFERENCES

National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov/cancerinfo/treatment/cam) the massage research database maintained by the American Massage Therapy Association (http://www.amtafoundation.org/researchdb.html), the database maintained by the Touch Research Institutes (http://www.miami.edu/touch-research/).

(http://nccam.nih.gov/)

REFERENCES

Ernst E. (2003). Safety of massage therapy. Rheumatism, 42, 1101–1106.

Fellowes D, Barnes K, & Wilkinson S. (2004). Aromatherapy and massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD002287.

Kutner JS, Smith MC, Corbin L, Hemphill L, Benton K, Mellis K et al. (2008). Massage Therapy vs. Simple Touch to Improve Pain and Mood in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Trial. Accepted for publication 2008, Ann Int Med.

Weiger WA, Smith M, Boon H, Richardson MA, Kaptchuck TJ, & Eisenberg DM. (2002). Advising patients who seek complementary and alternative medical therapies for cancer. Annals of Internal Medicine, 137, 889–903.

(A complete reference list for this chapter is available online at http://www.oup.com/us/ integrativemedicine).

Patients with cancer often suffer physical symptoms and psychological stress. Massage therapy, widely used by healthy people for relaxation, may have other specific benefits for patients in all stages of cancer treatment.

Patients with cancer often suffer physical symptoms and psychological stress. Massage therapy, widely used by healthy people for relaxation, may have other specific benefits for patients in all stages of cancer treatment. The use of massage therapy, with specific precautions in certain situations, is safe for patients with cancer.

The use of massage therapy, with specific precautions in certain situations, is safe for patients with cancer. There are few large, well-designed trials of massage therapy for patients with cancer; existing research suggests the most benefits for lymphedema and anxiety.

There are few large, well-designed trials of massage therapy for patients with cancer; existing research suggests the most benefits for lymphedema and anxiety. Though there is even less substantial research to support other claims, massage is often suggested for improved postoperative wound healing, sleep, pain, fatigue, constipation, and improved immune function

Though there is even less substantial research to support other claims, massage is often suggested for improved postoperative wound healing, sleep, pain, fatigue, constipation, and improved immune function Physicians caring for patients with cancer should ask all patients about the use of massage, consider recommending massage for anxiety and distress, and help guide the patient to a qualified massage therapist.

Physicians caring for patients with cancer should ask all patients about the use of massage, consider recommending massage for anxiety and distress, and help guide the patient to a qualified massage therapist.