A great product idea is certainly not enough to be successful. The product idea is usually the easiest part of building a product company. You also need sufficient funding and experienced management. My job at that time was developing the hardware, so I had limited interaction with the board of directors other than providing regular updates on the progress of the Pono player. But there was a lot going on behind the scenes.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Pono had a board of directors that was based on friendships, relationships, and personal recommendations, much the way many boards in small companies are formed. But few among this group were experienced in building and running a Silicon Valley startup.

The board consisted of the late Pegi Young, Elliot Roberts, Gigi Brisson, John Tyson, and Neil. Pegi was Neil’s then-wife, and Elliot was his friend and manager. Brisson was an investor and neighbor of Neil’s in Hawaii, and Tyson was a close and trusted friend of Neil’s and the board member with the most experience, from running his family’s business, Tyson Foods. Rick Cohen, a corporate lawyer with the law firm Buchalter in Los Angeles, attended board meetings as legal counsel for the company. Collectively, they had limited experience with high-tech startups.

MANAGEMENT

Elliot also served as Pono’s COO. He was a great manager and businessman with legendary experience in the music business. Early in his career, he had run a record company with David Geffen and was introduced to Neil by Joni Mitchell, one of his clients at the time.

While Neil began as Pono’s CEO, it was clear to him and to Elliot that the company needed a full-time leader with experience in building and running a startup, and most importantly, someone who could bring in more funding. Developing a new hardware product, even with a lean team, was costly and all-consuming.

EARLY INVESTORS

Financing to that point was mostly from Neil, Tyson, Neil’s artist friends, and a number of private investors, totaling a few million dollars. They invested because they believed in what Neil was doing and wanted to support his efforts.

Often, Elliot would express his surprise and frustration to me about how expensive it was to develop hardware. That was not unexpected because he and Neil had little experience in this area. Most companies that get into the hardware business for the first time have the same reaction. Hardware is expensive to design, build, and manufacture. In retrospect, I should have been more proactive by developing a more detailed development budget. Instead, I assumed that the money would follow as we crossed each development milestone. That pointed out another management deficiency we had—no CFO, resulting in a lack of accurate forecasting. Naively, I just assumed that Neil could bring in the funding we needed.

FINDING A NEW CEO

While Neil and Elliot took on the roles of CEO and COO, Neil also had his job as an active musician and Elliot continued to manage Neil’s career with a small staff in a downtown Santa Monica office.

Neil was constantly busy writing, recording, and promoting his new albums and left town for extended periods on worldwide concert tours. He was also writing his autobiography and had a few other projects on the side. Neil very badly wanted a CEO to take some of the load off his shoulders and to build the company, someone more experienced than himself.

Finding that person turned out to be a difficult effort that stretched for more than a year. I assumed it would be much easier than it turned out to be, but, in fact, it was difficult to find someone who felt the same way that Neil did about his mission. Although we read so much about the risk taking among Silicon Valley executives, we saw little of that among the potential candidates that came by. It didn’t help that the company was not well funded, which would limit what a new CEO could do in their first days. In fact, the new CEO’s first job would be to find money.

I had recommended to Neil and Elliot that they hire an experienced search person to find a candidate, but they and the board preferred to rely on personal recommendations and avoid that expense.

Pono went through a few trial candidates, those that Elliot would encourage to come in as a consultant and try to raise some funding as one of their first jobs. Some of the candidates liked the idea of working with Neil, but many wanted to run their own show. It was one of the few times where Neil’s involvement in the company made it more difficult to do something. While Neil’s association with Pono was important, it also attracted unqualified candidates and lookers who were more interested in the association with Neil than in the hard work the job entailed.

One candidate joined and, on paper, seemed promising. He had experience in the streaming music area and was well connected to the industry. But in short order he tried to recast all of Neil’s efforts in his own vision, including wanting to stop the Pono development and outsource it to another company that he had a relationship with, but that had little product experience of this type. He then announced on social media, to several board members’ horror, that he and Neil had just founded a new company together. He didn’t last long after that!

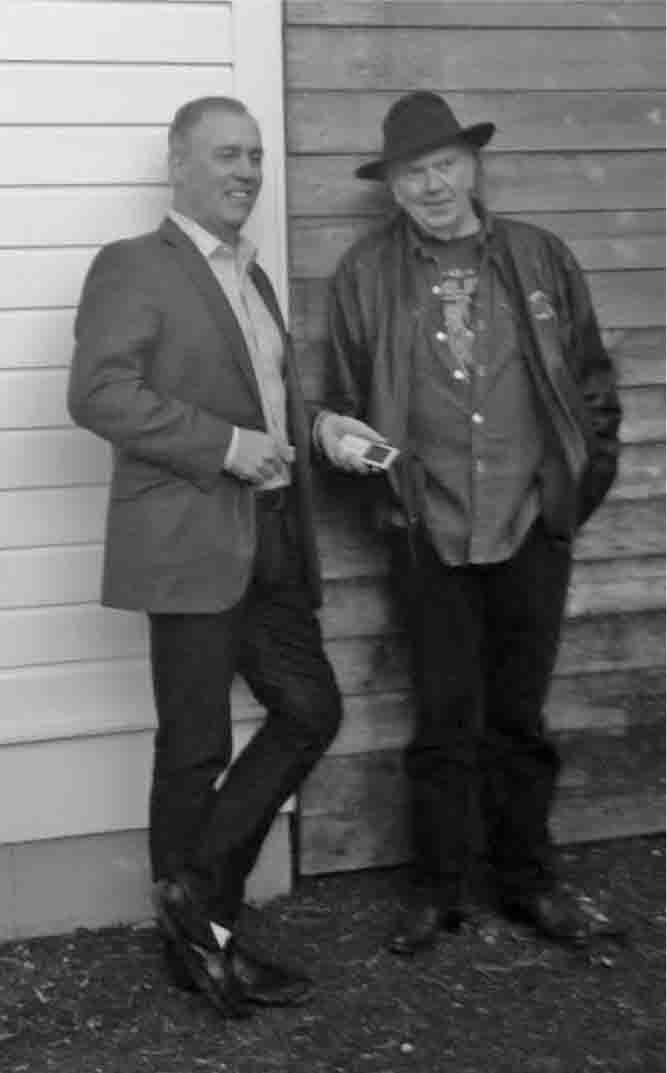

Eventually, a CEO was found. John Hamm was hired in April 2013. He came to us because of a chance meeting between his wife and Gigi Brisson at a TED conference in San Francisco. Hamm had the ideal background, with experience as an investor, board member, and management advisor to several startup and established technology companies. He also had a strong interest and involvement in music, as an audiophile and a board member of the Grammy Foundation. He complemented Neil’s skills with his own experience in building companies, raising money, and understanding music, marketing, and corporate governance. Hamm shared Neil’s beliefs about the pursuit of quality audio. He also brought credibility that could help with potential investors and had plenty of experience in raising money for cash-strapped companies such as ours. In addition, he was smart, charismatic, high energy, and personable.

John Hamm with Neil

Hamm articulated his thoughts well as soon as he joined:

The force of Neil’s will was an inflection point. Every time there’s a brewing grassroots movement, it always takes someone of stature to put their body on the front line. A lot of people talked the game of better audio, but Neil was the only one to put his badge on the table and lay across the tracks. Neil was willing to use his position in the industry to call attention to as much the shitty quality of MP3 as the great quality of studio masters.

He pointed out how bad MP3 is as a representation of an artist’s intention and to really expose that. What an insulting technical format it was to the effort artists put into their recordings. I remember when we were shooting video driving around Mulholland Drive and talking about the laborious task of making a record. The time it took to get a mic just right on a drum, the numbers of remixes, the work that engineers and producers would do. The fact that all of that is then substantially degraded by the format of playback. It would be like taking an artist’s picture and making a blurry copy.

Hamm’s business skills were a strong complement to Neil’s vision. The expectation was that Hamm could at last turn Neil’s vision into a business that could succeed and be successfully funded. It seemed like we had the perfect duo.

GETTING REAL

Hamm jumped right in and began to put into place the structure of a serious Silicon Valley startup company. We started meeting regularly at his San Francisco home to identify the resources we needed. We developed a budget and a detailed schedule that covered every key milestone to commercialization for each critical element: the player, the music store, manufacturing, and marketing. Hamm formalized my role as vice president of hardware and operations and expressed confidence that he could raise the needed money to bring on the additional resources we were lacking.

With the work on the music download store languishing and the scope of what was needed growing in complexity compared to what we’d originally assumed, Hamm recruited a vice president of technology, Pedram Abrari, the software counterpart to my position in hardware. Abrari had experience developing cloud-based software products and was a strong addition to the company. Abrari, in turn, hired a software design engineer, a software quality engineer, and an engineer with experience in building online stores.

Hamm also hired a business development manager, Randy Leasure, and a marketing director, Sami Kamangar (Pedram’s spouse). Considering the scope of our undertaking, we still had a relatively small group—fewer than ten full-time employees in addition to four consultants on the hardware team.

Hamm leased an office on the third floor of a small office building in the Potrero Hill area of San Francisco, where we could all work together. The office consisted of a large open area with desks and tables, and a small room next door, our listening room for testing and demoing Pono.

With the additional employees and our first office, we were a real company and our development progress accelerated. The elements of an online music store were defined, and intensive work on it began. The store had many complexities to it. Not only did it need an online storefront that was visible to the customer for searching, selecting, and purchasing music, it also needed a complex behind-the-scenes infrastructure to manage the music library, download the music, and conduct the financial transactions with the record companies and our customers. Last, we needed applications for both Mac and Windows—much like iTunes—for users to manage their music files and load them onto the player.

Kevin Fielding, our new software engineer, quickly created a much-improved user interface for the player, and Damani Jackson, our software quality engineer, worked full-time testing it on the new players we had built. Irina Boykova was responsible for building the online store, while Zeke Young, Neil’s son, focused on music content. Pono was becoming more real.

The Pono team: Irina Boykova, Dave Gallatin, Randy Leasure, Kevin Fielding, Dave Paulsen, Neil Young, Zeke Young, Sami Kamangar, Damani Jackson, Pedram Abrari, and Phil Baker

STILL MISSING IN ACTION

But late in 2013, a few months after Hamm arrived, we still faced a major issue: Bob Stuart still had not delivered his software that was to be incorporated into the player, the software designed to compress files to use less memory while retaining high-resolution sound. Making it available was part of an early agreement between Stuart and Pono in exchange for a sizable chunk of equity. But, as I later learned, the agreement was written in very general terms and failed to define the software with any precision. That probably made sense considering the agreement was written before we all really understood the specifics of the product we were to build, but Neil and Elliot wanted something formal in writing.

Stuart had been attending our monthly development meetings at Neil’s ranch as the team’s audio expert. But as we progressed with the development of the player, it was Gallatin who designed the player’s electronics, while Stuart provided suggestions and comments along the way. Stuart’s main contribution was to be his software.

In these meetings Stuart would describe his software in general terms with little specificity. He explained it as something very complex that involved encoding and decoding using both software and hardware. But he was always reluctant to provide specific details about when we’d see it.

I could sense that Neil was becoming frustrated and impatient, because that software was critical to completing and testing the player. It was not only Neil; the entire development team had begun to wonder whether we’d ever see anything. It made us all very nervous.

To keep moving forward, Gallatin added a programmable memory chip to the circuit of the Pono hardware design so that the software could be added after the player was built and bypassed in the meantime.

But we never received the software. I didn’t know if Stuart’s technology was not ready or if he was reluctant to provide it to us. I kept thinking that this was not the way a partner with equity should be behaving, but there was little I could do.

Finally, in our November monthly meeting, Stuart said he was ready to discuss the terms for Pono using the software. Hamm flew to the UK to meet with him and the investors in Meridian: the Richemont Group, a Switzerland-based company that owns a number of European luxury fashion brands.

The terms they proposed to Hamm included monthly payments, royalties for each player sold, more stock, and no exclusivity. The terms were much more onerous than Pono could afford and made no business sense based on normal industry standards. Not only would the software not be exclusive to Pono, but it also restricted what Pono could do with it. For example, if Pono was sold or licensed its player to be built or sold by another company, then his technology could not be included.

During these negotiations, Hamm explained our economics and tried to negotiate a more favorable arrangement. Discussions and negotiations continued for several months and included Hamm, Elliot, Neil, Cohen, and Stuart and his investors, but they never were able to come to an agreement.

When I interviewed Stuart for this book, he thought that Pono management had been unreasonable by not accepting his terms, because of the value his software would provide. Stuart felt its value was much greater than what Pono believed it to be. Stuart’s software eventually became the basis for a proprietary compression technology called MQA.

![]()

This turn of events was a huge disappointment and a serious blow. Stuart had worked closely with us for two years, since the beginning of Pono’s development, and we assumed he would provide this technology with terms we could all agree on. With my responsibility for getting the player designed, built, and tested, I was quite frustrated that this key element was unavailable while the players were otherwise completed.

This development could not have come at a worse time. It was late in 2013 and Hamm was working on bringing in outside investments, and one of the selling points of Pono was that it had this special technology that set it apart. While the Pono player would still work without Stuart’s software, it would have little to distinguish it from other players. Moreover, it was important that Pono meet the high expectations Neil had set for it. It needed a distinguishing feature to differentiate it beyond Neil’s involvement. We all were disappointed and wondered whether this would mean the end of Pono.

Meanwhile, the engineering for the Pono player had been completed, except for Stuart’s software. We decided to plow forward and complete the build of the next fifty players without it, incorporating all of the design improvements we had been working on since we built the first group of players. They’d be far from perfect but would be a major milestone, allowing us to put players in the hands of Neil, the board, and others for testing.