There was never any question that we’d need to build the Pono player in China to meet our schedule and cost targets. While we would have preferred to manufacture the players in the United States, it just wasn’t practical. The US is not competitive for building products like this because most of the components that go into it are made in China, such as the touch display, battery, and electronics. If we built the product in the US, we’d need to ship the parts well in advance, adding considerable costs and delays. When I examined the option at Neil’s request, I found that the player would cost more than double if it were made in the US. Most importantly, manufacturing it in China would allow us to do it much more quickly, using existing companies with lots of experience in building consumer electronic products, an area sorely lacking in the US.

LIAM CASEY

Shortly after beginning the player development with Neil, I introduced him to Liam Casey, the CEO of PCH China Solutions. I had worked with Casey and PCH on previous projects, and his company had experience in many areas of manufacturing, including building accessories for Apple, as well as a number of more complex products. He had a capable staff of manufacturing engineers, project managers, packaging designers, buyers, and other support personnel headquartered in Shenzhen, the heart of China’s consumer electronics industry.

PCH’s primary expertise was in logistics: packaging, shipping, and sourcing products and parts throughout China; doing some manufacturing; and providing direct delivery of products to customers all over the world. The company had gained its experience by working on accessories for Apple, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Beats, Fujitsu, and other consumer electronic companies.

The demands of these companies, particularly Apple, had given PCH the skills to work on products that were of the highest quality, beautifully finished, and with an excellent out-of-box experience.

While we could have reached out to other companies and conducted a manufacturing search, we had little time, few resources, and no significant financial history, which some companies required.

Another concern was product cost. Since the product was still being designed, any manufacturing agreement at this stage would be based not on a fixed price, but on a formula based on what the cost of the components (the BOM) turned out to be. Typically, based on the many electronic consumer products I’ve built in China, the cost of manufacturer charges equals the cost of the BOM multiplied by a factor ranging from 1.2 to 1.5, which accounts for the manufacturer’s cost of labor, overhead, and profit. The exact numbers are negotiated once the design is close to completion, when you have a better sense of the design, manufacturing challenges, and the volume.

Casey was an energetic, creative, and charismatic leader with some of the best sales skills I ever saw. He had a charming Irish accent and a can-do attitude that was contagious; people loved being around him. He was constantly traveling between the US, Europe, and Asia, spending much of his time in his modern Shenzhen offices. Behind his smooth facade was a smart, thoughtful visionary who was always looking to take on the next challenge. He had built skilled, capable organizations in Shenzhen, San Francisco, and Ireland, and was focused on servicing companies developing consumer electronic products. He loved working with startups and had founded one of the first hardware incubators in San Francisco, Highway1, where he helped entrepreneurs turn their ideas into products.

PCH had grown to almost a billion dollars in sales, but most of its business was low-margin work for Apple, much of it logistics and light assembly. He had been trying to diversify beyond Apple by taking on another large customer, the headphone company Beats. But once Apple bought Beats, he was back to having mostly one large and difficult customer.

So, our timing was good. Casey had been wanting to take on more challenging projects, such as playing a larger role in a product’s development by becoming involved earlier in the process.

Casey wanted to build Pono in his own factory, even though it was more complex than the accessories he normally built. He liked the high visibility of the product and the desire to support Neil’s efforts, and it was a way to expand his company’s expertise.

Liam Casey, CEO of PCH, our manufacturer

PCH proposed setting up a new production line especially for Pono. I worried that doing Pono was a larger and more complex project than he had typically done, and this might be a stretch. But with limited time, and few other options, I thought that PCH could do it. Unlike other companies, if we ran into a problem, I had the CEO’s phone number—actually three numbers, for each of the three iPhones he carried.

TIME OF GREAT INTENSITY

The next six months from the completion of the Kickstarter campaign to the manufacturing of Pono players was the most intense, pressure-packed, self-reflecting period of time I’ve ever spent developing a product, a result of the tight time pressure and high visibility. Yet, there was no direct pressure from Neil, Elliot, or John. They just assumed I knew what I was doing, and that it would get done. That added even more pressure.

On many of my product development projects there had been a larger team, with my role primarily being to direct their efforts. But this project was different. We had a tiny hardware team with a very limited budget. So, I decided that I needed to be much more hands on, involved in the product at a much deeper level than I had been for a long time. I felt the responsibility and commitment to Neil to get this right. And we needed somebody to pay attention to every detail while still not micromanaging the team. Experience had taught me that, with startups, one detail could kill or seriously hobble a new product as well as the company itself. You can’t afford recalls or do-overs. You get one chance to get it right.

While Pono was a relatively straightforward, even predictable design effort, as with any product, there are always a myriad of issues that arise, many impossible to predict. If you’re too optimistic, you might miss a potential issue that could seriously impact the product, and if you’re too pessimistic, you end up worrying about many things that never happen. I was the pessimist this time and would worry about all the things that could go wrong. With such a small team and with my being in charge, I felt it was incumbent on me to do so.

WORRY LIST

Writing down my concerns had been useful when developing other products, and was therapeutic as well, so that was where I began. I created my “Worry List.” It contained potential issues that would keep me awake at night—high-risk items that could jeopardize the product’s performance, quality, schedule, and ultimately its success. The list was easy to compile, having done so for many products and experiencing almost every kind of problem over the years.

Top on my list was audio quality. We were packing hundreds of tiny components from Hansen’s new design into the small player. So many things could go wrong, even if his design worked. Would everything fit? Would the audio be noticeably better, and would his design even be manufacturable? How would we test the audio quality, and how consistent would it be across all units? When I asked Hansen about these worries, even he didn’t know for sure. He was honest, which was his charm. “I’ve never done anything quite like this before in a high-volume portable product,” he said, “but I sure hope it all works.”

One of my other big concerns was the Pono’s touch display. Creating a custom color touch display from scratch was too expensive and would have required committing to buy a very large volume—perhaps 100,000 pieces—to get a willing supplier. Instead we selected an off-the-shelf two-inch color display with a touch panel that was being used in pocket-size cameras. We found just one company with this size of display that was willing to work with us. And while the display was fairly standard, we still would need some customization to make it fit.

I was also worried about battery life, how long it would last between charges. Hansen’s design would consume more power than the amplifier chips they replaced. We had chosen the largest possible battery that would fit, but until we built prototypes using the actual circuitry and fine-tuned the firmware, battery life was difficult to predict. We hoped for ten hours of play, but early calculations predicted only three. We eventually were able to get to seven hours. Had the life been much shorter, we might have had to consider redoing the entire mechanical design to accommodate a larger battery.

We debated how much memory to build into the player. Because high-resolution files use more memory, what would be enough? Would customers still expect to carry thousands of albums in their pocket? We selected a 64GB memory chip to be built into the player and provided a memory slot for adding additional memory. At the time, 64GB was the sweet spot for the cost-versus-memory curve, as it offered the most memory per dollar. We were so concerned about the customer’s need to store many albums at once that we included an additional 64GB memory card with the player at the outset, so that customers would have 128GB, enough for eighty to a hundred high-res albums. That added $30 to the player’s cost. We later surveyed customers and found that few cared about player memory, because they could keep their files on their computer and easily load what they wanted to hear, so we eventually eliminated the extra memory card. It was not lost on those of us who had agonized over losing Stuart’s memory-saving software that it wasn’t that big of an issue, after all.

MORE HELP

As I took on more of the development and manufacturing of Pono, I realized I needed an additional engineer to focus all of their time on quality and manufacturing. We needed to deliver products that worked well and were free of defects. We couldn’t afford to suffer from early failures. It would be embarrassing for the player to fail, even worse than not shipping on time. I wanted an engineer familiar with quality, testing, and manufacturing, one who would be willing to spend lots of time in China immersed in all of these issues with PCH and the part suppliers.

I searched for candidates using LinkedIn and found Greg Chao, an engineer from Silicon Valley with lots of experience in product quality and manufacturing and who had worked on many hardware products being made in China.

MORE PROBLEMS

As expected, we encountered a variety of problems over the next few months as we went from building prototypes to beginning production. We seemed always to be scrambling to find parts. Lead times for electrical components were often several months, but we needed them in weeks, so we had to find them on the secondary market at elevated prices. Sometimes PCH or their supplier forgot to place an order for parts, and we had to scramble. Not having a specific part, even one that cost less than a penny, would halt production.

A few supplier problems occurred that caused us to debate whether we should change to another supplier and start over. The company that assembled the electronic circuit board had difficulty building it because of inexperience with assembling the memory onto the processor. We debated whether to wait and see if they could solve their problems or find someone new. To make things more difficult, every company in China tells you “no problem,” so it’s hard to know the true facts. We stuck with them and they eventually figured it out.

One morning after arriving on one of my frequent trips to China, I asked PCH to take me to the battery fabricator that they had selected based on a referral. A fabricator buys the power cells from the battery manufacturer, in this case Samsung, and adds a custom protection circuit and connector. After arriving at their offices, we were aghast at what we saw: a dirty and disorganized factory with sloppy assembly practices. We quickly switched suppliers, perhaps avoiding a calamity down the road.

These experiences led me to bring in an old friend for several months, Reynold Starnes, a retired engineering VP who had headed up Hewlett-Packard’s desktop computer group, to evaluate the suppliers and work with PCH to procure parts. Starnes was an expert on Asian manufacturing and would work with his counterparts at PCH.

TOUCH DISPLAY

Meanwhile, the touch display was giving us problems during prototype testing. Our software quality engineer, Damani Jackson, noticed during his testing that the displays on some Pono players would react on their own, as if someone had touched the display. It was random and hard to reproduce, but it occurred often enough to worry us. The effect was that a song that was playing would stop or another would start playing on its own. We called it “false touch.” Every problem gets a name!

Dave Gallatin spent several weeks digging into this, and after much sleuthing, discovered the cause—spurious electronic signals between the two circuits controlling the display and the touch screen. We informed PCH and Greg Chao flew to China to meet with them and the display company. After they did their own investigation and were able to duplicate the problem, the display supplier said that the only fix was for them to redesign the circuitry in the touch display to eliminate the electrical interference, a process they estimated would take about four months. That was a shock and one we just couldn’t accept. It would be a huge blow to meeting our promised delivery date.

After discovering the cause, we were able to induce failures on about half the players. Gallatin kept working on the problem and thought he might be able to come up with a solution. Ten days later, he had developed a clever but very complex fix that would use firmware to automatically have each player analyze the characteristics of its display and then make an adjustment to reduce the likelihood of a false touch—essentially have each Pono test and repair itself.

It took another month to design, test, and implement, but we were uncertain whether this fix would work well enough on all of the players to be able to ship the product. Would it reduce the 50 percent failure rate to 10 percent or 5 percent? We really wouldn’t know until we began production and were able to build and test hundreds of players.

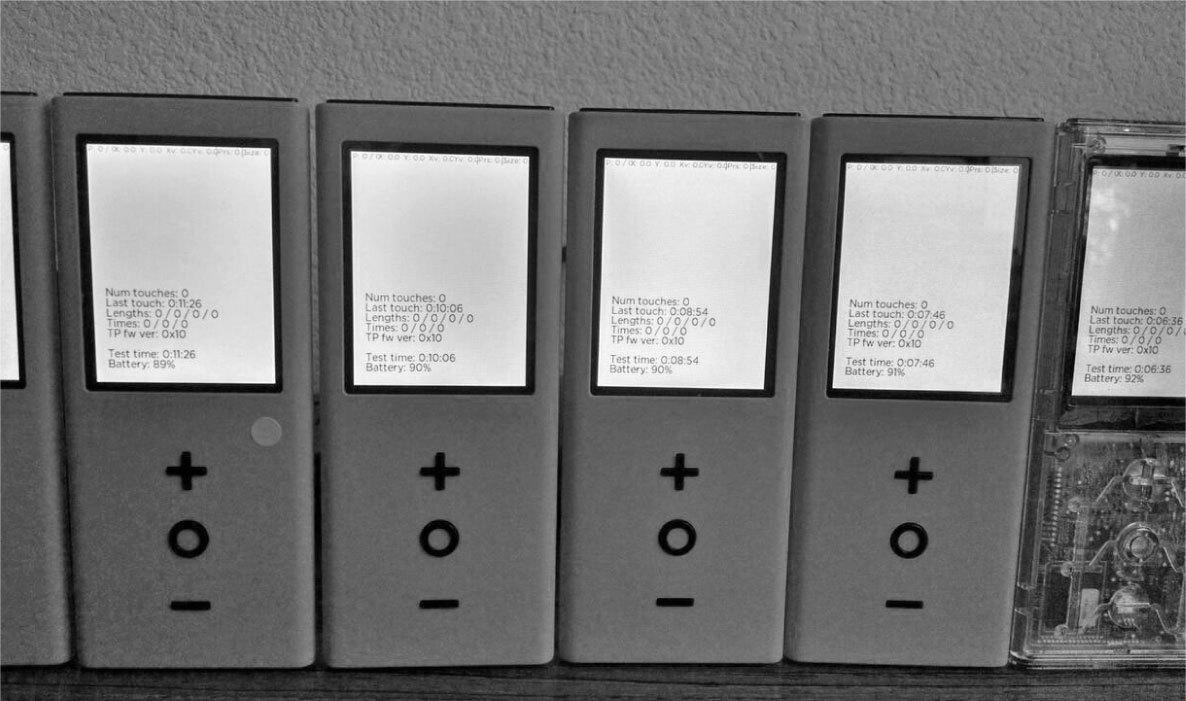

Until that could happen, all of us in the company worried about this on a daily basis. PCH added a test to the assembly line where they’d try to induce false touch on every player for twenty minutes at an elevated temperature, where the problem had occurred more frequently. We eventually reduced the occurrence on production units to close to zero, and it was never an issue once we shipped the players.

Testing for false touch

What we went through with Pono, dealing with a myriad of problems and surprises, was no different from what most products with any complexity experience. Every product has issues, many unanticipated and not discovered until hundreds or thousands of them are built.

While all of this was going on with the music player, another team was hard at work on the other big requirement of Pono, a method by which customers could browse, purchase, and download music into the player: the Pono music store.