The relatively peaceful days of the first two months became fewer and fewer as the dog days of August descended upon the growing school. As the age, size, and behavioral problems of the new enrollees increased, so did C. D. Griffin’s headaches. No student embodied these frustrations more than a teenager named Spurgeon.

Griffin’s introduction to Spurgeon should have provided a clue, as noted in his diary on August 21st. “Miss _____ called with a note from Mrs. Johnston asking me to take her brother if possible. As Miss _____ thought he would be a hard boy to control and hard to keep here, we decided it would be best to wait till we had the lock on the dormitory door before we attempted to care for him. At present we have 11 boys and the dormitory door wide open.

On another subject, the day did provide something positive as it may have planted a seed that would later germinate into something very fruitful for the school. “At five o’clock I dressed the boys all up. We boarded the lumber wagon and went to the National Guard Encampment down near East Lake. The boys behaved very nicely. The band playing and drilling interested them very much indeed.”

A week later, some of the rebellious behavior that would plague Griffin for months began in earnest. After spending the day in Birmingham running errands, Griffin returned home to find trouble. “When I reached home found Charlie _____ had succeeded in getting away from Mrs. Prey. I took Jimmie in a buggy and went in search. Met John with the wagon the other side of East Lake. They had caught the runaway boy. I had obtained a pair of shackles from Judge Feagin for use on runaway boys. Sloss and Charlie are still wearing chains. Fastened the shackles on the ankles of Sloss and Charlie.”

The diary did not state what indiscretion Sloss had committed, but it landed him in the same predicament as Charlie. Two days later, Griffin wrote: “At five o’clock we loaded all but Sloss and Charlie into the wagon and took them to see the soldiers drill. Sloss and Charlie are still wearing chains and are somewhat mortified.”

Griffin was somewhat offended himself the following Saturday after a conversation with General Johnston, his boss’s husband. Griffin had gone into Birmingham to report on the damage caused by a night of torrential rain, and his assessment was not well received. “The General thought I was mistaken about the water, wanted to know why I had not plowed and sowed a patch of turnips, said I had all the time there was, said for me to come home, and have the manure hauled out. They do not seem to realize that we are living with no conveniences but are doing the best we can with what we have. I was so completely discouraged by the General’s questioning that I came home at once and will say no more if the rain undermines the house.”

Things got no better for Griffin over the following days. John, his right-hand man, fell and twisted an ankle, resulting in several days’ bed rest; the wash woman quit and a replacement had to be found; and another of the boys, John, ran away only to be brought back in shackles. To top it off, he received a visit from his favorite general. “General and Mrs. Johnston and two daughters showed up at a very inconvenient time for visit. Very busy and because Mrs. Johnston was not familiar with road, I had to drive to the further corner of our land to take them back very late. After returning from seeing them to the main road, I had my supper to eat, boys to put to bed, milking to do, etc. It was quite late when I finally had my work done.”

His work was about to get harder, for on September 24th, the long-awaited Spurgeon arrived on campus. “A short time after breakfast, two men came, one a sheriff or policeman, and with them was Spurgeon _____ and his belongings. Spurgeon is a very large boy and there had been quite a scene at the home where the boy was arrested as he declared he would ‘get even’ with the mother and sisters for having him sent here. He is a pretty hard case. Very large for his age—16 years—and very revengeful.

Only three days later, Spurgeon made his presence known. “Miss _____ called early in the forenoon and paid $8.50 for Spurgeon’s care for a month. Spurgeon was very dramatic and would not speak to his sister. He made such a fool of himself I finally took him downstairs. Miss _____ felt very bad about her reception but was not at all astonished.”

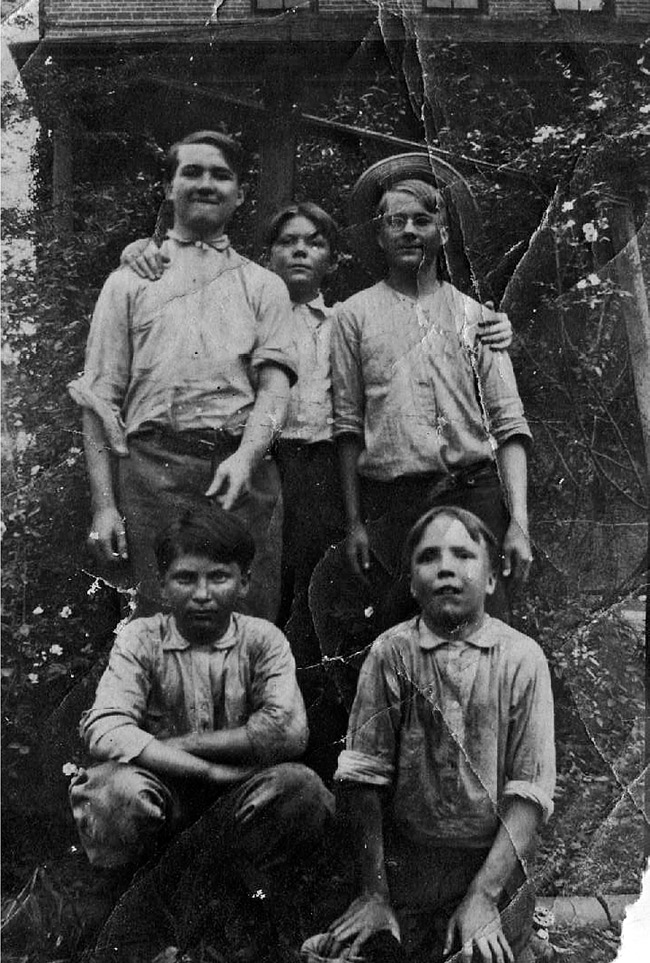

A group of the school’s earliest students are shown in this picture taken by fellow student James Dawsey in the early 1900s. It is not difficult to detect a little mischief in their faces.

The next day, Griffin reported that “Spurgeon ran away. John Embree jumped on Dollie and gave chase. I helped later, but we both returned without him. Went to town and purchased candy for boys. Found Spurgeon being detained at home in shackles and seemed subdued. We hope to send him to Nashville very soon.”

The next day, Griffin provided this update on their problem child. “Spurgeon still wears shackles. For nearly a week now, I have slept in the dormitory near Spurgeon so as to be prepared if there should be any outbreak.”

Whether it was an act of hopelessness or hopefulness, Griffin was soon ready to give Spurgeon a try at home according to this entry dated October 17th.

“Miss L. came to see Spurgeon. I recommended his going out on parole if he would promise to behave. Miss L. has a job promised him. Spurgeon seemed much pleased at the prospect of going home and very willingly signed a paper that he would obey his mother in all things, keep away from bad company and theatres. He is to go sometime next week if he behaves himself. I file his promises with this paper. John took his shackles off this evening after supper and the boy seems perfectly happy.”

Spurgeon was not the only boy giving Griffin fits—literally. “Before we were ready to leave the table this morning, Ernest _____, our new boy, showed signs of having a fit. I had John take him downstairs and he had quite a violent time. I wrote a note to Mrs. Johnston asking what to do with him as we had no time to look after him. I sent the note by Jimmie. Mrs. Johnston said for me to take him to town and have him sent to the poor farm.”

Even with all the excitement involving Spurgeon and company, life carried on at the school. An example of the day-to-day minutia included a trip to Red Mountain to gather nuts, the usual Sunday evening sing-alongs, frequent visits from Mrs. Johnston and her friends, and of course, the weekly baths, as described by the superintendent in his entry for Sunday, November 11th.

“A very busy day. Water too cold for the boys to use the creek and house full of company Saturday and were too busy for the boys to bathe last week at all, so it must be done today. After breakfast had two boilers of water put on the cook stove in the playroom and our three tubs put in the room. Boys had to bring water from the spring and carry the water out after bathing. Of course it took a long time to bathe 15 boys in this way, so it was nearly noon when I was through and could turn the boys over to John and change my own clothes.”

On November 27th, the school celebrated its first Thanksgiving. A Mrs. Walter in Woodlawn donated a full dinner for the boys, and Mr. Prey and John _____ went in the wagon to pick it up. The lone sour note of the day came when a boy named Chester tried to pull a ruse in the presence of his parents. Griffin explained it like this:

“During the forenoon, Mr. and Mrs. _____ called to see their son. He had a very pitiful tale to tell. He had left off his underwear so as to tell his mother I wouldn’t let him wear it. He told the boys he was going to leave off his shoes and stockings so to tell them the same story. His mother felt for a while that her darling boy was dreadfully abused, but when the other boys informed her that he left his underwear off without my knowing it, she said Chester was a really good boy only that he would not mind, would lie, and would not stay at home evenings. The father seemed to think that the boy was in the proper place and said that he should stay here till his record was what it should be.”

There was one positive development for the day. “According to an agreement made some time ago with Johnnie _____ and his parents, I let Johnnie go home on parole today. I think he will be alright and he promises to sign a paper tomorrow to that effect.”

On December 5th, Ernest _____, the fitful one, made his return. “During my absence, Mrs. _____ came with her son and a letter from Judge Feagin saying he was anxious to come back. Mrs. _____ brought some medicine for the boy to take four times a day, some pills to take occasionally, and a bottle marked ‘poison’ and a syringe. When he has a fit, he is to be given two drops of the ‘poison’ liquid, in a severe case four, but never more than five under any circumstances. Had I been at home I should have refused to accept him. As it was, I told him I would keep him until he had one of his spells and then he must go back to town as we could not afford to spend the time to watch him as there were so few of us. We are sorry for the boy as he appears to be a nice little fellow, but his mother wants to shirk the responsibility of caring for him.”

Over a period of three days in early January, two new boys were sent to the school for most unusual offenses by today’s standards. One boy, Edgar, age fourteen, was sentenced for stealing rides on trains. Hovater, age seventeen, took it a step further by beating his way onto trains.

A much more serious offense is mentioned on January 27th. “While we were eating breakfast a ring at the front doorbell was followed by the ushering in of Mr. Powers of Mobile, son of the Sheriff there, and a boy, John _____, sentenced to us for manslaughter for five years. It seems his mother lives on the street leading to the canning factory and the factory girls have been in the habit of throwing stones at the house when passing to and from the factory. It was very annoying and one night the girls were extra boisterous and the owner of the house tried to catch them and called to John to bring his pistol. He had a very small pocket pistol. He ran into the house, brought it and fired, killing one of the girls instantly. His mother was sentenced to the pen as accessory to the murder.”

For whatever reason, parole must not have worked out for Spurgeon, for he reappeared in this entry from January 30th concerning a benefit program the boys were attending. “Spurgeon always blunders so in drilling and makes such a fool of himself when there are any ladies around that we thought best not to take him. The new boy John from Mobile has not learned to drill and I had no ‘Sunday clothes’ for him and Hovater, our convict boy, is wearing chains yet, so I did not think best to take him. We left these three boys with Mr. Melton. Boys very well behaved. Boys remarked that they had never had a better time in their lives.”

On February 1st, another new resident, Clarence, was brought to the school and made quite an impression on Griffin. “He was so dirty and filthy that I wanted to handle him with tongs. Did not look as though he had ever bathed and did not seem to know how to bathe. I put his clothing on the stove and burned it up.” His stay, however, was short-lived, for on February 12th, Griffin conceded that “The Board decided we could not keep Clarence as he is so near an imbecile we could not bother with him and it was thought best to send him back to the mines.” In that day “imbecile” was regularly used in referring to a mentally deficient person.

On March 25th, the school narrowly averted a disaster. “The clouds became so dark we could not see to do anything. The wind was very high and drove the water through the roof and under the doors till there was not a room in the house without water all over everything. We were more fortunate, however, than people in Birmingham for they had a regular cyclone there. Fourteen people killed and a large number wounded.”

A few days later, a storm of another type was brewing on campus. “The boys reported that Spurgeon had asked the boys to run away with him if Mr. Embree went to town. He has been trying for some time to stir up the boys to run away. And when a plot of his to get about six of the boys to run away with him was unearthed, I promised the next one who mentioned the subject of running away some punishment. So, stopped long enough to put Spurgeon in the dungeon. Then went on to town. In the evening, we old folks colored about 90 Easter eggs for the boys after the boys had gone to bed.”

The next day, as the boys attended church services and celebrated with Easter eggs and candy, Spurgeon remained in the dungeon.

The diary did not divulge when Spurgeon again saw the light of day, but the ever-conniving youngster was at it again on May 27th. “Spurgeon had taken advantage of my absence and had run away again. He was plowing in the onion patch and when at the other end of the patch from Felix, he deliberately left his mule and ran.” A week later, the fearless fugitive was captured and returned to the dungeon.

By July 5th, Spurgeon had earned his release from the dungeon and was back on the farm under the care of Felix. Using the same modus operandi as before, the determined delinquent once again left his mule and plow in the dust. In the diary’s last mention of Spurgeon on July 15th, the superintendent paid Mr. McDaniel, the local constable, five dollars for his capture.

About two weeks later, according to the diary, the school celebrated the first anniversary of the laying of the cornerstone on the main building. As the school family assembled around the cornerstone, chances are Spurgeon had a front-row seat from the dungeon below.1

Griffin’s diary comes to a mysterious end on September 12, 1901. It is not known whether the remainder has been lost or for some reason Griffin simply stopped keeping his daily account of the school’s happenings. What is known is that Griffin submitted his resignation in June 1904 and the board accepted. There were references in the next year’s annual report to “dissatisfaction among the employees,”2 and in a subsequent report Mrs. Johnston alluded to “debts incurred without our knowledge by the first superintendent.”3 Dr. Hall, the minister who recruited Griffin’s successor, simply said that the superintendent’s “ideas were not in accord with those of the Board.”4

Upon Griffin’s resignation, the board acquired the services of William Connelley, an executive on loan from the local Tennessee Coal and Iron Company to serve as interim superintendent. Although Connelley served only a year while a permanent superintendent was found, he created the beginnings of a foundation on which the center of rehabilitation flourished, most notably with the “Open Door System” that Weakley also incorporated to create a caring atmosphere.

Perhaps it is the gracious David Weakley, who became superintendent in 1905, who summed up Griffin’s resignation best when he wrote, “I never knew Mr. Griffin, so I am in no position to comment on his successes, nor his failures. No doubt, due to lack of money, divided public opinion, and often public hostility, he suffered many heartbreaks and disappointments.”5