David Weakley thought he was where he was supposed to be in October 1904. He was on the staff at the Tennessee Industrial School, and he and his wife were happy in their work. But God, and one of his most persistent children, Elizabeth Johnston, thought otherwise.

Weakley was born on June 12, 1878, in Newbern, Tennessee, the son of a Confederate soldier. His family had been prominent and Weakley County was named for his ancestors. He received his education in the local public schools, followed by studies at Newbern Seminary. He had also completed special courses in vocational education, business administration, psychology, and mental hygiene.

In 1898, Weakley went to work as the manual training instructor at the Tennessee Industrial School in Nashville. This school, one of the first of its kind in the South, had been founded in 1885 by Edmund W. Cole after he was touched by the large number of children orphaned by the recent cholera epidemic in the city. Professor William Kilvington became the school’s first superintendent and subsequently the mentor of David Weakley.1

“Professor Kilvington was a man of rare ability, charm, and attainments,” Weakley said years later, “and whatever success I may have had, I owe mainly to his teaching and training, and I know of no one during my time who has made a more lasting contribution to the welfare of the children of the nation.”2

In 1902, Weakley married Katherine Stamps, a recent graduate of Peabody College, who had been hired to teach at the industrial school. With Weakley’s promotion to assistant superintendent of the school in 1903, the young couple appeared to have their future mapped out in Nashville.3

It was in the next autumn that Johnsie and the board members dispatched Dr. J. D. Hall, a Birmingham Episcopal minister, to visit Weakley. Hall informed the twenty-six-year-old schoolmaster that the board had been studying such institutions as his around the nation and was impressed with the educational and vocational programs, as well as the overall atmosphere, that his Tennessee school offered. Hall also told Weakley about Mrs. Johnston and the fledgling school in Alabama. The minister informed the young administrator about Mrs. Johnston’s experiences teaching in the mines and her vision for the state’s boys. He related her efforts in convincing both the populace and the legislature of the critical need for such a school, and the passage of the bill creating the school with its all-female board of directors.

Finally, Hall got around to sharing that the board was dissatisfied with the current superintendent, and asked Weakley if he might be interested in the position.

Years later, Weakley recalled that he was initially reluctant. He thought that the women were probably a “bunch of daydreamers, fault-finders, and busy-bodies” who would be difficult to work with on a daily basis, and he tactfully admitted as much to his visitor. Hall quickly told him otherwise and praised the board members as “level-headed, Christian persons whose only interest was to do something really worthwhile to advance the welfare of their less fortunate little brothers; that they were giving their time, money and themselves to a most worthy cause without hope of favor or reward.”

“Mrs. Weakley and I discussed the matter at length,” he remembered, “and despite his plea, we gave him an unqualified no. We tried to explain our reasons for not accepting. To him these reasons did not seem valid, but he reluctantly returned to Birmingham.”4

Hall and those who commissioned him in Birmingham were not deterred, and he returned to Tennessee three weeks later. “I have come to pray with you and your wife about going to Alabama to head our boys’ school,” he told the couple. “Mrs. Johnston is also praying in Birmingham that my mission will succeed.” Hall spent the evening at the school and told Mr. and Mrs. Weakley more about the institution in Alabama. Weakley admitted that he was impressed by Hall’s sincerity but was far from being convinced that he needed to leave the stable situation in Tennessee for the uncertainty of a new and struggling school. However, as Hall left the next morning, Weakley did promise that he and his wife would make it a matter of prayer.

There was no further communication for weeks, then out of nowhere the Weakleys received a letter informing them that the board of directors of the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School had elected him as their superintendent and Mrs. Weakley as matron. “We were appointed to jobs which we did not seek and for which we did not apply,” Weakley recalled. “We didn’t understand it, but felt that we must go. There must have been a greater Power than any human force that guided our decision. Mrs. Johnston said it was the hand of God that brought us. I have never known anyone with so much faith and who so completely relied on Divine guidance as Mrs. Johnston. Surely she walked and talked with God, and she lived in a spiritual atmosphere of confidence and trust that was an inspiration to all those who came in contact with her.”

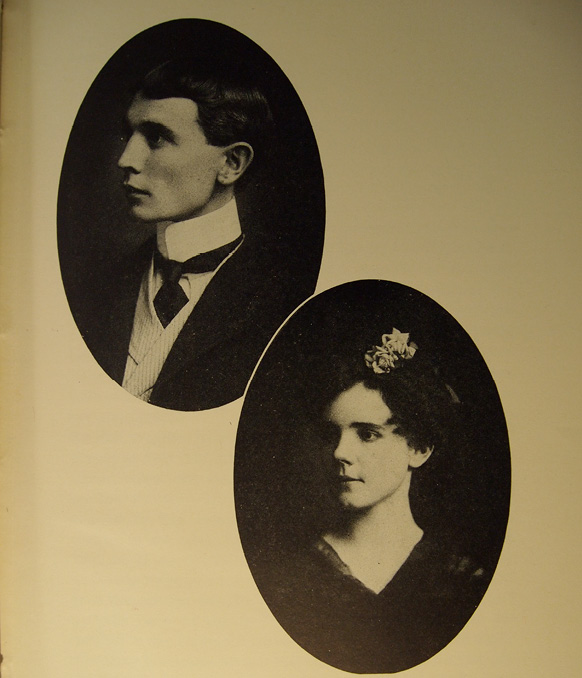

Mr. and Mrs. David M. Weakley are shown at the time of their appointment as ABIS’s superintendent and matron in 1905.

God must have been involved, because there was certainly nothing about the school or the situation at this point that would have been humanly appealing. “Somehow, it never occurred to us to visit the school and look over the situation before we accepted the jobs. Maybe it was providential, for had we done so, I fear we would have returned to Nashville,” Weakley admitted. Nevertheless, the couple arrived in Birmingham in late February to look at their new home and place of employment.5

Weakley remembered their initial visit in great detail. The couple was met at the train station by Hall and a student named Charlie, “a lanky, sandy-haired boy with beautiful white teeth and an engaging, friendly smile.” Their hosts were “driving a beautiful bay mare hitched to a slick looking new surrey with fringe around the top.” He would later learn that the surrey was purchased by board members out of their own pockets just for the occasion. With Berta the mare leading the way, the foursome traveled the eight miles to the school in cool, pleasant weather with the remnants of a recent snowfall still covering the ground.6

On arrival at the East Lake campus, the students gathered around to size up the husband and wife who would become their new teachers. One precocious boy got right to the point by asking, “Are you the folks what’s going to run this school? If you is, I hope you will get us some school books what we can learn.”7

The youth’s spotty grammar pointed to just one of many deficiencies the experienced administrator would notice during his visit. As they surveyed the grounds, they discovered the conditions were quite poor. There was little in the way of landscaping and red mud was everywhere—a sticky nuisance with which Weakley was totally unfamiliar. The words that immediately came to his mind were “devastation, disorder and ruin.” He later confessed that during the first evening on campus, they were searching for a way to make a “graceful exit” to return to Nashville, where they had been promised their former positions would be waiting.8

The next day, a Sunday, the Lord truly began to work. The Weakleys went with the boys and staff to worship services, which he later described as “simple and impressive with a sincerity of purpose, accompanied by beautiful and tuneful singing.”

The afternoon was spent with the boys who had initially impressed him as a “motley, unpromising bunch of unkempt youngsters who cared nothing for the better things of life and who had no ambition for self-improvement.” But after a day of mingling and getting to know them on a deeper level, “we found how wrong we were. Their friendly attitude and intelligent questions, and their responsiveness were amazing and we later learned many of them possessed fine minds, were ambitious and eager to learn.”

Equally inspiring was the resolve and enlightened attitude of Mrs. Johnston and the board members. Weakley described in some detail the differences in the typical institution of the day and what the women in Birmingham envisioned for their school.

Schools in this era were generally “custodial,” Weakley wrote, with “no serious thought given to the individual boy, either to their spiritual, emotional or educational needs. The regulations under which they lived, the training and discipline were often useless and sometimes relentless and cruel. Mrs. Johnston and the Board felt that the Alabama school should be a place that would strengthen and inspire; a home that would prove a blessing and a benediction.”

In spite of the difficulties and challenges they saw all around them, there was something drawing the young couple toward this opportunity. Mrs. Weakley summed it up quite simply when she told her husband, “God has sent us to the place.” It would be their home and their life’s calling for the next forty-three years.9

And Johnsie’s prayers had been answered again.