The 136-acre site Mrs. Johnston had found for her new school may have looked right out of the Twenty-third Psalm, but it would take more than green pastures and still waters to accommodate hundreds of delinquent boys. That duty would fall to the board of directors and their capable staff.

Not long after purchasing the initial plot of land, a problem arose, or as Mrs. Johnston would call it, an opportunity. It was discovered that the young man who was an heir of the original seller still owned the adjoining property where the spring that fed the land was located. He was willing to sell, but at age nineteen, he did not have legal standing under Alabama law to enter into the transaction, so Mrs. Johnston went to court to have the young man declared an adult so he could sell the property. Just when things were looking up, a local neighbor came forward to claim that he was part owner of the spring. He, too, was willing to sell, not only his interest in the spring but his property as well, bringing the total acreage to 270 acres. Both new acquisitions were made through donations by the board members and other friends in the community.1

The only existing structure on the expansive piece of property, according to the first Superintendent C. D. Griffin, was an “old log cabin, which was filthy, and about to tumble down from old age. We cleaned it up the best we could—whitewashed the walls and scrubbed the floors.” This first building was so unsuitable as living quarters that Griffin and his assistant eventually turned it into a dining hall and erected a white tent nearby to serve as a dormitory for the staff and first group of boys.2 Thus began a construction program that would eventually result in twenty-three buildings erected over the first fifty years of the school’s existence.3

The board immediately authorized construction of a suitable building, completed in late 1900. The board decided on a three-story wooden structure that would sleep seventy-five boys, but also contain school rooms, vocational shops, and other space. The State of Alabama provided only $3,000 for the first year of the school, with more than three times that much in cash and supplies contributed by the community. Most of the labor was donated by local craftsmen.4

Johnston Building.

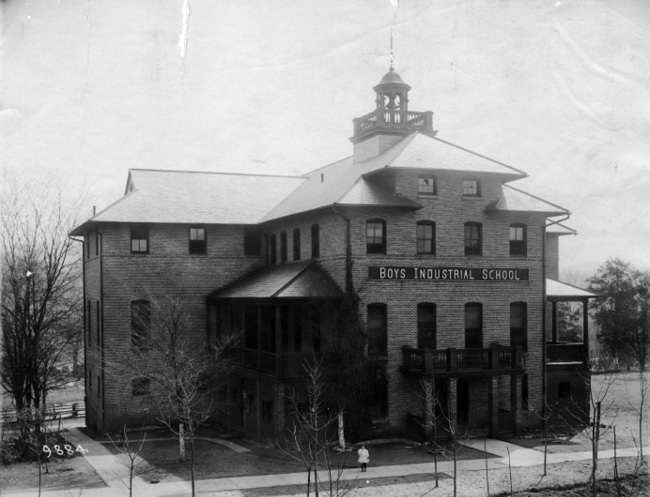

The increase in the student population led to a request for a second building in 1903, which the legislature approved along with another appropriation of $3,000 to supplement what the board would raise independently. The building, to be used entirely as a dormitory, was a three-story brick veneer with a slate roof and bell tower. It was very modern for the times, with electric lights, steam heating, and plumbing. When the building was completed, the board requisitioned the $3,000 from the state to pay the balance due, only to be told by the governor that more pressing needs had arisen and the money could not be released. Through Mrs. Johnston’s determination, a loan was obtained and disaster averted.5

Birmingham Building.

The Campus

Despite Mrs. Johnston’s description evoking biblical comparisons, Mr. and Mrs. Weakley would have begged to differ when they arrived in February of 1905. “There were no walks or driveways, only mud, bushes, and briers surrounding all the buildings. Mud holes and ditches were in great profusion.” The energetic couple immediately went to work. “We divided the boys into work squads, and started to cutting out the underbrush, filling in the low places, and planting grass. We had to do this the hard way by the pick and shovel method. We did not have a wheelbarrow. I begged some lumber from one of my friends who owned a sawmill, and we built a number of plank walks.

“In the Fall of 1905, we started planting shade trees and shrubbery,” he continued. “The boys dug these trees from the nearby woods, and in due time, they grew into wonderful shade trees. There were only a few trees on the campus when we arrived, and now there are hundreds of them. When the trees became large enough we had trouble with the boys climbing in them and swinging on the limbs and breaking them off. We solved this problem by having printed on waterproof paper and tacking on each tree the poem ‘Trees’ by Joyce Kilmer.”

Weakley credited his wife with the inspiration and the planning that made the campus into the pastoral setting it eventually became. “Mrs. Weakley assumed the task of beautifying the campus and the result is evidenced today by the beautiful trees and shrubbery. She chose the location of all the buildings and planned for future expansion. Her love for beauty, system and order was one of her outstanding characteristics. If she saw an ugly spot, she would screen it with a rose bush or a climbing vine. Our campus, in due time, compared favorably with that of a well-kept college.”6

This view shows the campus’s first three buildings, as well as the trees planted by Mrs. Weakley. In the foreground is the “ugly gully” that was eventually filled.

An interior view of one of the early dormitories illustrates the barracks-style accommodations that were common for much of the twentieth century.

Alabama Building/Johnston Hall

The third building on campus, completed in 1907, was the first structure of the Weakley era and also the first paid for entirely by the State of Alabama. It was originally dedicated as the Alabama Building, but was subsequently named Johnston Hall in honor of the school’s great lady. The building was three stories of solid brick, with a full basement. The structure was to serve several functions, such as classrooms, staff living quarters, assembly room, kitchen, dining room, and boys’ dormitory—a classic example of the congregate plan.

At the turn of the century, there were two schools of thought regarding the layout and operation of a boys’ institution. The congregate plan advocated having all of the school’s activities under one roof so as to enhance security. This was the method employed by the original House of Refuge in New York and other early institutions. The alternate approach was called the cottage system, which called for housing the boys in smaller cottages, with functions such as the academics, dining, vocational shops, and the like being located in separate buildings. Over time, ABIS would transition to such a system.

Alabama Building, later Johnston Hall.

At the time the structure was raised, funds were insufficient to excavate and finish the basement. In anticipation of doing this at a later date, the walls were built to the proper height that would allow the boys to dig up the dirt and roll it out in wheelbarrows; the carpentry shop would then complete the interior. As this process got underway, a major obstacle was encountered. A huge limestone rock twelve by ten by eight feet was unearthed—much too large to go through the basement door. Attempts to break it apart with sledge hammers and steel chisels proved fruitless. The only alternative appeared to be blasting powder, which could possibly damage the foundation of the massive building.

Engineers and contractors were discussing their limited options when a barefooted boy who had been observing the proceedings interrupted their conversation.

“Mister, if that was my rock, I’d tell you what I’d do.”

“Son, what would you do?” the engineer asked kindly.

“Well, sir,” the boy replied, “I’d come right alongside of this rock and I’d dig a hole big enough to put the rock in, and after I’d hauled out the dirt, I’d prize the rock in the hole and cover it up.”

After some consultation with his colleagues, the professional engineer acknowledged the common-sense approach of his young amateur colleague, and that was exactly what was done.7

The next major project at the campus was a three-story wooden building to be used exclusively as a shop for all of the vocational programs. The state was unable to make any appropriations, and there were insufficient internal funds to hire an architect or laborers, so the carpentry instructor designed the building and the boys did all the work. Practically every vocational department at the school was involved in one way or another, and the boys pitched in willingly as they realized the resulting facility would be for their own benefit. The first floor housed the printing, barbering, plumbing, electrical, auto repair, and machine shops, while the second floor held carpentry, tailoring, the shoe shop, and band room. The third floor was reserved for storage.8

Kilby Hall

Kilby Hall was a two-story, brick dormitory built in 1921. Rather than the large, barracks-style rooms found in some of the other dorms, this building had small rooms for three boys each. The woodworking shop made the furniture, and the student paint crew decorated the rooms in pastel colors, making the interior homelike and attractive. Hot and cold water was available in each room.9

Bush Chapel

One of the most impressive of the early buildings was the Bush Chapel, built in 1923. The money for this place of worship was donated by long-time board member and treasurer, Mrs. T. G. Bush. Weakley described it as being of “colonial architecture, simple in beauty, classical in design, and presenting a picture of spiritual restfulness.” A bronze plaque was placed over the entrance of the 500-seat sanctuary proclaiming “those that seek me early shall find me.”

The Bush Chapel is one of the few remaining buildings from the early days of the campus. The family assumed the responsibility of preserving and maintaining the chapel upon Mrs. Bush’s death in 1930.10

McLester Hall

Another dormitory was added in the late 1920s. The two-story edifice had rooms that accommodated four boys, with built-in beds, lockers, and study desks for each boy made by the woodworking class. The first floor contained a living room and space for recreation and hobbies.11

Mechanic Arts Building

This vocational building, also added in the late 1920s, replaced the original wooden shop built twenty-five years earlier. The older boys helped with the construction of the facility, with one crew working in the morning while another attended academic classes and the two groups exchanging places in the afternoon. The two-story brick structure was designed in the shape of a “T” and contained space for eight trades on the ground floor and six trades, plus storage, on the second floor.12

Craighead Hall

Craighead Hall was built in 1932 with assistance from President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) to serve as a kitchen and dining hall, with special accommodations for staff and guests. The boys’ contributions to this endeavor consisted of making venetian blinds for the windows and doing all of the painting. The building was named for long-time board member Mrs. Erwin Craighead.13

Throughout most of Mrs. Johnston’s adult life she had one other consuming passion in addition to the beloved school for her boys. Mrs. Johnston was an ardent admirer of George Washington. She became involved with the Mount Vernon Association and later served as a board member and regent of the organization. An avid collector of relics pertaining to the nation’s first president, she later helped retrieve articles that belonged in his home.

In the early 1930s, the Highland Book Club built Mrs. Johnston a cottage on the grounds of the school, and she dubbed it Little Mount Vernon. It became a place where she could spend her last days in the company of her boys. The students made her a four-poster bed that was a replica of President Washington’s, and a set of draperies in the cottage actually came from Washington’s home. A mirror that adorned a wall in the cottage was made from a walnut tree on the Virginia estate, and many of the plants in her garden came from Mount Vernon.

After Mrs. Johnston’s death, Little Mount Vernon continued to serve the school in numerous ways, including several years as the library.14

Adele Goodwyn McNeel School

This academic building of the late 1930s was named for Mrs. McNeel to recognize her contributions as board president succeeding Mrs. Johnston. The brick facility contained twelve classrooms, a library, and special rooms for art, music, and handicrafts. The structure also contained a 500-seat auditorium, complete with a “moving picture projector.”15

Weakley Hall was built in 1940 with the assistance of the WPA as another dormitory. Each of the nine bedrooms on the second floor housed four boys, with a lavatory, bed, locker, and writing table for each one. The first floor was devoted to a living room and recreation and bathroom facilities. Once again, the students lent a hand with the painting, furniture, and even the curtains.16

Underwood Hall

This final building project of the Weakley era was another dormitory built on the same general plan as McLester and Weakley halls, although somewhat smaller with seven bedrooms for four boys each. The building, constructed during the administration of Governor Chauncey Sparks, 1943–47, was named for Mrs. John Lewis Underwood, another deserving board member. In a fitting epilogue to this chapter on the growth of the campus, it is interesting to note how much construction costs and property values had risen in fifty years. The first biennial report indicated that the total value of the property and the one building at the end of 1900 was about $18,000. The construction and furnishing of Underwood Hall alone was close to $100,000.17

1 Weakley, 33.

2 Second, 11.

3 Birmingham News, Hugh M. Sparrow, “Boys’ Industrial School Is Guide to Misguided,” January 4, 1945.

4 Weakley, 130-131.

5 Ibid., 132.

6 Ibid., 14-16.

7 Ibid., 135-137.

8 Ibid., 138-139.

9 Ibid., 143.

10 Ibid., 148.

11 Ibid., 150.

12 Ibid., 154.

13 Ibid., 157.

14 Ibid., 152.

15 Ibid., 160-162.

16 Ibid., 162-163.

17 Ibid., 164-165.