Everyone has heard the old adage about idleness being the devil’s workshop. That was not a problem at the new school for wayward boys. The Alabama Boys’ Industrial School had a few workshops of its own to provide instruction in a vocation as well as life.

The founders of the school did not choose the word “industrial” lightly. From a meager beginning of four trades, the school eventually reached a peak of nearly twenty different vocations in which they offered training.1 Unlike some of the nation’s early institutions for delinquent and destitute boys that forced their residents to work at menial tasks as a means of punishment, the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School from the beginning seems to have placed its emphasis on rehabilitation rather than retaliation.

“Every thoughtful citizen must agree,” Mrs. Johnston wrote the governor in the school’s first annual report, “that it is a duty the State owes its wayward and criminally disposed boys to remove them from temptation and inspire them with hope, whilst training brain and hand, rather than punish them by association and contact with our worst criminals and hand them over to predestinated destruction.”2

The able board president then went on to relate a sad and dramatic tale that spoke volumes about the plight of many of the state’s at-risk boys, and the government’s responsibility to act.

“The children themselves have an instinctive sense of this obligation on the part of the State. It is related that when a boy was on the way to the scaffold to be executed for a capital felony, he turned to the minister present and in piteous tones exclaimed: ‘Mister! O, Mister! Tell them I ain’t had no chance, no how!’ This should never be uttered by a boy of Alabama again.”3

In giving the youngsters under his care the opportunity for which the boy pleaded, Superintendent C. D. Griffin took a practical, two-fold approach to the value of industrial training. In modern correctional parlance, he saw its benefits in terms of both managing the boys while in the institution and providing them a future upon release.

“We need more room, more industries and better equipment for these we have already established,” he wrote. “An idle brain is the devil’s workshop and while we give the boys play hours, we make them work and study in due proportion. Our aim is to prepare them at the Industrial school for supporting themselves by an honest trade when they are turned out into the world.”4

Early records indicate that printing, carpentry, blacksmithing, and leatherworking were the first skills selected toward that end.

Printing

“We have tried to equip the Printing Department with first-class, up-to-date appliances for printing,” Griffin reported at the end of his first year. With this fledgling effort, the school’s industrial program was underway. He further mentioned that the printing operation had been most helpful in producing letterheads, envelopes, and even a school newspaper.

“We have a paper started which we call the Boys’ Banner. It has been cordially received by institution papers throughout the United State and we have quite a large exchange list. We have had a great many complimentary notices from superintendents of various schools, for it is a rare thing to start a paper within the first year of the school’s existence.”5 This student-produced periodical would be a staple of the institution for fifty years.

In Griffin’s next report, printing appears to have suffered the growing pains associated with the entire institution.

“The printing department has been kept up all the year and our magazine used, but not as promptly as we would like, as we have had so little help and so much to attend to that some duties have been more or less neglected.”6

When Colonel Weakley assumed the helm of the school, the printing department received an infusion of new blood—and more ink.

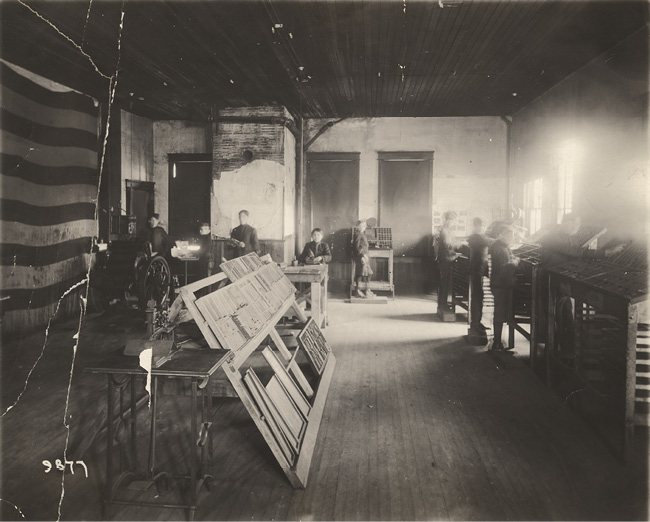

“The printing office is one of the most interesting and at the same time one of the most useful shops on the place,” Weakley related. “About an average number of 12 boys, under a competent instructor, are given daily lessons four and one-half hours in typesetting, color work, job and press work, besides acquiring practical experience in the newspaper line.”

The ABIS print shop provided training for the boys and published the school newspaper.

During this period the school newspaper continued to grow. “This department produces semi-monthly a small twelve-page periodical, The Boys’ Banner, which is distributed among the children and friends of the institution; it also brings to us many bright, newsy exchanges, which the boys delight to read.” Over the years, the The Banner would evolve into a monthly and later a weekly publication.

Apparently Weakley did not find the department’s printing equipment in quite the pristine condition that his predecessor had boasted only three years earlier. “Our press, an old second-hand affair, is in very bad shape and should be replaced by a new one or rebuilt at the factory,” he lamented. “The face of some of the type is completely worn out and is no good whatever, except as old metal. It will cost about $500 to put this department in first-class working order.”7

The school was fortunate during Weakley’s years to receive donations of printing equipment from the Birmingham News and Birmingham Age-Herald, as well as special appropriations from governors Thomas Kilby and Bibb Graves. On occasion, equipment was donated by national companies that specialized in making printing presses. Weakley commented that when the school had an opportunity to get equipment, it always sought to get that which would make the boys most marketable. His thinking was sound, for most of the students left the school with jobs in hand at local newspapers, and a few with the Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C.8

As the school grew and perfected its training, the scope of the printing operation expanded as well. In addition to letterheads, envelopes, and the like, the printing class eventually began producing all the forms and documents used by the school’s academic department and hospital, as well as all of the school’s promotional literature and the annual report.

In the school’s twenty-fifth annual report, Weakley even suggested that with a little more support in funding and equipment, the operation would be able to assist the State of Alabama in some of its overall printing needs.9 Not bad for what started as a handful of teenagers with ink smudges on their fingers and faces.

Carpentry

In the formative years of the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, carpentry—or its variations—was probably the most useful of all the trades, as the boys literally built the institution around themselves.

“We have a few cheap tools and with these some of our boys have made excellent progress in the art of carpentry,” C. D. Griffin wrote in his report for 1901–02. “An engine house, a large outhouse, green house, tables for the dining room, and numerous shelves, doors, and cupboards can be exhibited at the school.

“With our new scroll saw, a Christmas present, we hope to have a collection of finer work to exhibit next year. The boys are interested in wood carving. I have bought a set of carving tools and hope to show some work in our paper before long of their making,” the first superintendent stated.10

Furniture made in the school’s carpentry shop awaits placement in one of the dormitories. The various shops on campus helped the school become very self-sufficient in its operations.

As with most of the trades, carpentry made rapid strides with the arrival of Colonel Weakley who was himself a former instructor in this skill. He went to great lengths in his first report to discuss its intricacies and its benefits. Although most carpenters certainly appreciate the skills required of their work, probably few have ever described their work as eloquently as did Weakley:

“Manual Training, or Sloyd, is any form of constructive work that serves to develop the powers of the pupil through spontaneous and intelligent self-activity,” he explained. “Sloyd is truly a constructive work; the pupils are taught after they have made a perfect mechanical drawing of the object they wish to produce, that it must be constructed according to strict specifications which are shown on their drawing—not too long or too short—but just right, with no imperfection of any kind. By means of drawing, sawing, planning, etc., the pupils are taught to become skillful with their hands, patient, accurate, clean, careful, persistent and persevering; thereby strengthening the brain through the medium of touch and sight, at the same time cultivating a respect, love and value of rough labor.”

Weakley went on to explain to the uninformed reader the depth of the training that would be provided the novice carpenters. “No set of models has to our knowledge been designed that express the complete idea of manual training,” he wrote. “Therefore, while we are operating this department which we deem so essential, we shall use freely the best ideas found in the Swedish, German, Russian and American courses as the basis of our teaching, at the same time reserving the right to draw from our own originality . . .” 11

A set of table and chairs made by James Dawsey’s carpentry students is ready to be moved into the dining hall.

James Dawsey (far left) and two friends while students at ABIS. Dawsey later returned as the carpentry instructor and remained on staff for 47 years.

To begin his pupils’ training, Weakley acquired through donated funds the tools to furnish twelve regulation work benches, featuring drawing boards, planes, saws, hammers, braces, bits, and other tools. Later, with appropriations from the Kilby administration, power tools such as sanders, band saws, drill presses, and the like were added. The school even had a machine to make its own brooms and brushes, and the school farm grew the broom corn to supply the bristles.

As the size and skill level of the carpentry class increased, the boys took on greater challenges. Their first projects were a shed and barn for the farm, and later the boys erected the vocational program’s first shop building in 1910. Over the years, the boys would have a hand in the constructing most of the buildings on the growing campus. Eventually, the class made all the furnishings for the buildings, including beds, chests, tables, chairs, and desks. As noted earlier, the boys even made venetian blinds.12

The evolution of the carpentry and woodworking shop is embodied in the life of James Dawsey. He was a student at the school in the early 1900s, and after serving in World War I, came back to serve as the carpentry/woodworking instructor. Dawsey’s grandson, Scott, provided the details of this lifelong love affair with the school:

As a boy, my grandfather was very artistic, He could take a piece of wood and make anything out of it. He decided he was going to make a covered wagon. So, he went down and bought all the stuff at the hardware store to make a covered wagon and he charged it to his daddy and made his daddy mad. Now, his daddy was in the State Legislature at the time, so I guess Mrs. Johnston had been with the Legislature trying to get funding and he knew about the school. So, he sent him there. It was just silly, silly, silly. When my grandfather went, he was going to stay for a few months or a year maybe—that’s what they intended to send him down there for just to straighten him up. But he didn’t want to come home; he loved it. Mrs. Johnston was a mother to those guys. They loved Mrs. Johnston.

Like many of the boys, James Dawsey left the school to enter World War I. Upon his return to Alabama after the war, he received a letter from an old ABIS friend. Scott Dawsey said:

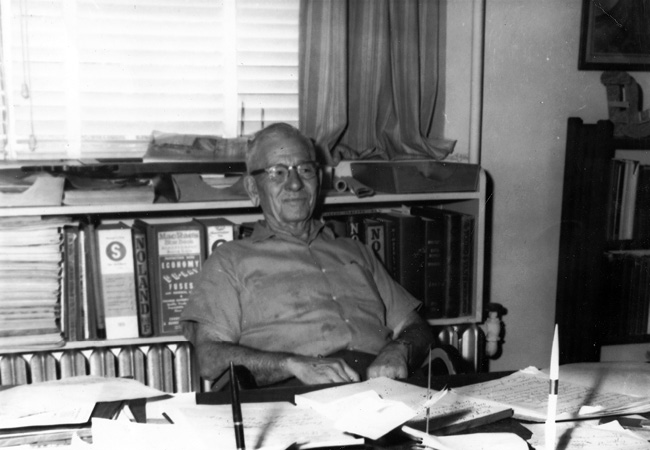

James Dawsey sits at his desk late in his forty-seven year career as ABIS carpentry instructor.

Lonnie A. was a classmate there with my grandfather, and he later became a teacher there; he was in charge of one of the military companies and ran one of the shops. Lonnie sent him this letter in 1919 in Hartford, where my grandfather’s family home was, telling him how great things are, telling him the pay is better, and that they’ve got biscuits every morning. He tells him you need to come back up here. So, he goes back up there and he stays 47 years.13

Colonel Weakley would have been the superintendent at the time that young James Dawsey was sent there for the covered wagon fiasco. Weakley and Mrs. Johnston always had a soft spot for any of “their boys” and nothing made them prouder than for one of them to come “home” to work at the institution. This is clearly evident years later when Weakley wrote of Dawsey’s tenure at the school and his ability to shape more than just wood.

“James Dawsey is a capable and dedicated person who sets a high standard of excellence on the work of the boys,” Weakley said of his former student turned faculty member. “He is especially gifted in designing beautiful carved art pieces that were a surprise to all those who saw them, and they wondered how boys could be taught to produce such delicate and exquisite work. This instructor has been with the school for a long number of years. He has never faltered in his work, and his interest in the welfare of his pupils has grown throughout the years. They come to visit him from far-away places and they write to him from foreign lands.

“His greatest work has not been with material things, but that he has been able to instill in the hearts and minds of hundreds of boys a sincere purpose and a feeling of confidence that has enabled them to become qualified to go out and face the world unafraid.” 14

Blacksmithing

No other trade at the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School conveyed the feelings of the era in which the school was established than the blacksmith shop. These were the days of the horse and buggy, and there were horses to be shod and buggy axles and wagon wheels to be repaired. The blacksmith shop began as a necessity to curtail expenses but evolved into a training opportunity.

“The latter part of April, we purchased and installed a set of blacksmith tools consisting of forge, anvil, tongs, stocks, dies, etc. which have proved a saving and a valuable addition to the school,” Colonel Weakley related in his report for 1905. “Heretofore, when we wished a bolt or a wagon repaired, or a plow point sharpened, we were forced to make a trip to East Lake, not only paying for the work done, but losing valuable time from our farm.

“The blacksmith shop has amply demonstrated its usefulness,” he continued, “and if we can secure the means, we hope in the near future to employ a regular class in forge work and horse shoeing.”15

In short order, that hope was realized, as Weakley remembered in his personal papers. “We decided to start a shop and were able to secure as instructor a man of long experience in the trade. He was a person of excellent character, an outstanding workman; in fact, he was an artist in shaping, welding, and designing beautiful and useful articles constructed of wrought iron. As usual, it was a question of money, but after talking the matter over with Mr. B. F. Moore, President of Moore and Handley Hardware Company, to my surprise he said he would like to donate the major part of the equipment, which consisted of two anvils, forge, hammers, tongs, etc.

“We built a makeshift shop . . . under a beautiful spreading elm tree. In weeks we assigned six boys to learn the trade, and we were in the blacksmith business,” the superintendent explained. “The instructor was pleased with the setup, and the boys were elated, and their progress was rapid. We were able to keep our farm equipment in excellent condition, put shoes on the mules, and besides making needed repairs, the instructor taught the boys to make gate hinges and fasteners and such articles as fire tongs, pokers and shovels. Later, they made two complete two-horse wagons. They were neatly appointed, and had the appearance of being factory-made. We used them for years.”16

Henry Ford and the progress that rode in with his Model-T eventually made the blacksmith shop obsolete. “As time passed, and the use of the automobile increased, the need for the blacksmith shop also passed,” Weakley admitted, “so, we converted the blacksmith shop into an automobile repair shop. Here again, our friends came to our aid and donated several automobiles. This was a move in the right direction, and during the years, we have been able to run out many a good workman.”17

Shoe Shop

For most of the Huck Finns at the school, new shoes were a luxury, but it was one to which they soon became accustomed.

“We have a poorly equipped shop, but the boys have learned to do some very nice work,” C. D. Griffin wrote of one of the school’s first trades. “We are making some new shoes, keep our old ones well repaired, which saves us much expense. Of course, most of our boys are barefoot during the summer.

“We have also commenced making harness with our limited facilities and we have repaired our harness and have made several bridles. Considering that these boys have never done any work before to amount to anything and now are able to do this work, it shows we are doing something toward making industrious citizens out of raw material.”18

The following year, Griffin’s report showed continued progress in this class. “During the summer we put in a supply of lasts, patterns, and tools for the making of shoes,” he wrote. “We found an old second-hand sewing machine, which we could afford to buy, and now the boys in the shoe shop are making some excellent shoes, which out-wear the shoes we buy, and do not cost as much and teaches the boys in the department a good trade.” 19

During Colonel Weakley’s early years at the school, a situation occurred that is indicative of how things were done until the new institution could gain its financial footing. “One day I heard there was a small shoe manufacturing plant in Birmingham that had failed in business and was being sold at auction,” he related in his papers. “I inspected this machinery and found six or eight factory machines in excellent condition that I knew we could use to advantage. I bid them in at less than $400, but after I had bought them I realized I did not have the money, so I rushed to the people who sold us our groceries and asked if I could borrow this amount. They were very obliging and we used this machinery for a long number of years to great advantage. We were able to make our shoes in a more or less professional manner and more rapidly. The product turned out not only useful, but nice looking.”20

In his 1915 report, Weakley made the following assessment of the shoe shop. “The shoe shop, under a competent instructor—one of our own students—has done excellent work: 635 pairs of shoes, worth $2.25 each, have been made, 3099 soles put on old shoes, 2035 heels repaired and put on, and 1116 patches applied.21

By most accounts all of this work was done with approximately ten students placed in the shoe shop. That’s a lot of soles for ten young souls. Perhaps the explanation is found in a 1931 report by the instructor, Don Smith. “Most of the boys like the shop and work to learn all they can, and to be sure, they are looking forward to the time when he can go to his home town and obtain work for himself. I have three boys who are ready for jobs, and they appreciate the fact that the institution has helped them to get ready for their vocation. These boys are very enthusiastic.”22

Whether it was wood, leather, or boys, the school seemed to have a knack for turning raw materials into useful products.

1 Thirty-First, 64.

2 First, 6.

3 Ibid.

4 Second, 19.

5 Ibid., 14.

6 ABIS reports, Third Annual Report, (East Lake: Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, 1903), 4.

7 Sixth, 29.

8 Weakley, 25.

9 ABIS reports, Twenty-Fifth Annual Report, (East Lake: Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, 1925), 15.

10 Second, 14.

11 Sixth, 30-31.

12 Weakley, 19-23.

13 Scott Dawsey, interview by author, Tuscumbia, Alabama, December, 2009.

14 Weakley, 19-21.

15 Sixth, 30.

16 Weakley, 18.

17 Ibid.

18 Second, 17.

19 Third, 4.

20 Weakley, 27.

21 ABIS reports, Fifteenth Annual Report, (East Lake Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, 1915), 13.

22 Thirty-First, 62.