If one of today’s juvenile reform schools supplied their inmates with Army rifles, the public outcry would be deafening. But the students at the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School proved the wisdom of that decision over and over again.

The idea of adding a military component to the school was mentioned by the superintendent in the Second Biennial Report covering 1901–02. “We have not overlooked the military training of our boys,” wrote C. D. Griffin. “Regular drills are given them every week and they can march and go through all the military evolutions of a battalion as well as the manual of arms.” A photo contained in an early souvenir booklet from the school shows these feeble beginnings with a dozen little boys in knee pants and suspenders giving a feeble salute.1

This photograph from an early souvenir booklet shows the first group of boys at the school standing at attention. Over the years, a precise military regimen would emerge from this feeble beginning.

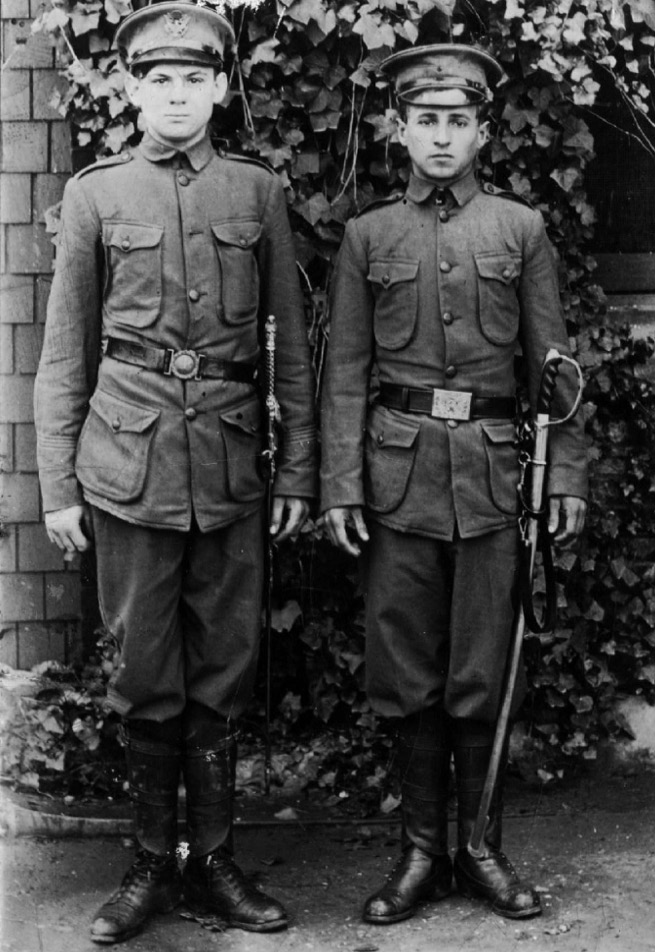

Two young cadets appear in dress uniform. Armaments were often furnished through special congressional appropriations, and uniforms were made in the shops on campus.

Mrs. Johnston took the concept a step further in her report to the governor for 1905. “The officers and local Board strongly advocate military discipline for the institution,” she proposed. “This feature is embodied in the most advanced reform institutions. To be under military restraint and punished by court-martial does not seem to humiliate a boy as do some other modes of correction. Far be it from me to advocate the abolition of the rod, but I do endorse the old divine who said, ‘we should pray three times before we whip once.’

“We earnestly desire the cooperation of your Honor in introducing the military system into our work,” she continued. “This with uniforms would do much to increase esprit de corps of our institution, without which our school cannot succeed.”2

The undertaking continued to grow during David Weakley’s first year on the job. “We trust in time to be able to secure at least seventy-five rifles, and form a military company . . .” the superintendent wrote in his first report. He further stated that such a concept would be “not only a valuable adjunct to our mode of discipline, but increase in the bosom of the boy a feeling of patriotism and love for his country.”3

In his personal papers, Weakley elaborated on that point. “We never tried to make our military training tough, but tried to impress upon the pupils the value of discipline and obedience. We felt in all our dealings with the boys, example and precept were more contagious than threats and punishment. Friendship, justice, devotion to duty, with examples of disciplined living, are forces that help turn back the tide of mediocrity and slovenly existence.”4

From that meager beginning, the program grew in both size and scope. U.S. Senator Oscar Underwood guided a bill through Congress that provided the school with seventy-five military issue rifles. Over the years, several state leaders, including Governor Chauncey Sparks, furnished the school with uniforms and other equipment.5

The entire school was soon organized along a military structure, with as many as five or more companies. The boys began to participate in certain ceremonial exercises to start each day, along with having drill two to three times a week for about an hour and a half each session. The Alabama National Guard designated Weakley a colonel as the highest ranking official in the institution. The head of the Military Department was given the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was often a seasoned veteran of some branch of the armed forces.

Weakley described in one of his annual reports the process of mustering in a new cadet. “The new boy is placed in a platoon known as the New Boy Platoon. There he is given instruction without arms, such as position of attention, parade rest, rest, at ease, facing, eyes right or left, hand salute, side step, back step, mark time, quick time, etc. Then he is given a rifle and instruction in the manual of arms before he drills with his company. This takes up a great deal of time and is one of the difficulties of the military instruction for the new boys . . . Here we attempt to tattoo discipline on the boys’ minds.”6

In one of his departmental reports, Lieutenant Colonel H. C. Wood described the total development of the boy as he goes through this demanding routine. “It trains the raw material into a well-ordered being, into the young man ready for the duties and responsibilities of the future,” he wrote. “The untrained young man is woefully handicapped in his struggle.

“Military training teaches the young boy how to stand and walk and hold himself erect,” he continued. “It gives him vigorous outdoor exercise so that gradually his chest expands and his muscles grow firm. It disciplines him, it develops self control as well as obedience to proper authority, and it prepares the youth for better citizenship.”7

The boys prepare for drill. The officers, with swords, are members of the ABIS staff.

The boys set up camp at Roebuck Springs.

As the program gained traction, it attempted new and greater challenges. The school started holding drills on Sunday afternoons, which the public was invited to attend. In 1925, this was expanded to an Annual Military Day, with many of the boys being recognized for their achievement. Prizes and medals were given for best-drilled company, best cadet officer, best-drilled cadet, and best all-around boy in the school as determined by the students. Essay contests were held with the boys writing on topics pertaining to citizenship, patriotism, and the like. The commanding officers of the Alabama National Guard and the governor were often in attendance. Weakley estimated that on occasion as many as 4,000 spectators attended from the community.

“I think these public exhibitions gave the boys a feeling of being a part of something worthwhile, and created in them a feeling of self-respect,” Weakley commented. “In addition to all this, it gave the public a chance to participate, and to come into our school face to face with the student body, and see first-hand the operation of the school.”8

One of the most endearing stories from the school’s history occurred during one of these ceremonies. According to Weakley, a dog appeared on campus one day, and the boys in one company asked if they could adopt him as their mascot. The colonel gave his permission. Soon the boys had trained their dog to march with them and obey all commands. They even used the school’s sewing shop to make the mutt a uniform complete with insignia that identified him as a corporal.

Soon, all the companies had somehow acquired dogs for their squads, and each began trying to outdo the next in the ranks of their four-legged recruits, with none lower than sergeant major. This reached the breaking point one day during the Annual Military Day. The companies filed by the reviewing stand full of local dignitaries and officers from the Alabama National Guard. In perfect step, there appeared a unit led by its mascot proudly wearing a jacket displaying the two stars of a major general! The reviewing officer that day from the National Guard happened to be only a one-star brigadier general. “General,” said his aide, as he suppressed a smile, “I see you are outranked today.” The obviously embarrassed Weakley busted all dogs back to the rank of private from that day forward.9

Another exercise of the school’s Military Department took the skills of the cadets to another level. “For several years we had our own military encampment and the U.S. Army regulations prevailed,” Weakley wrote in his papers. “The boys lived in tents, did regular guard duty, went through the regular drills, with time provided for tactical study and recreation.

“This was, perhaps, the only time where a school of our type permitted the entire student body to leave the campus for such a purpose,” Weakly surmised. “It was a Herculean task, for provision had to be made for cooking, lighting, sleeping, health sanitation, etc. The training proved invaluable to those who entered into World War I.”

War, unfortunately, became a reality for many of the boys. According to Weakley, more than 700 ABIS alumni fought in World War I and close to 800 in World War II.10 Each time one of those young men answered the call to serve, he showed the enormous value that military training had on his own life and for his country.